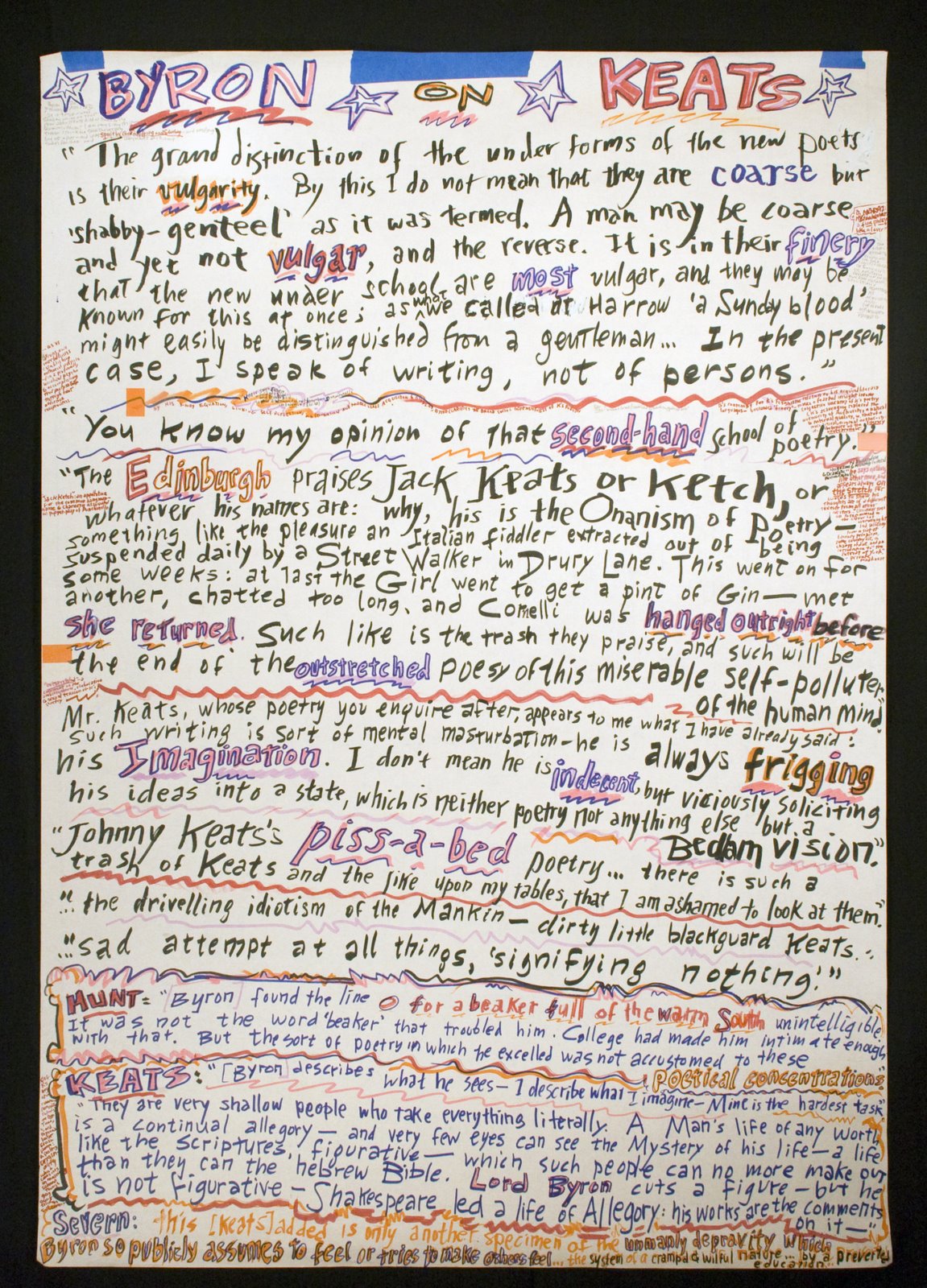

or the Lucid Ardors of Recreating the Past

Bronze head of Emperor Hadrian, found in the Thames, London (British Museum)

Bronze head of Emperor Hadrian, found in the Thames, London (British Museum)

for Nora SawyerThere came this comment on

Vistas of Limbo from a younger classicist friend:

"This reminds me of the Emperor Hadrian's 'animula vagula blandula' (please

pardon my clumsy translation):

Pale little vagrant soul,

my body's guest and friend,

where are you off to now,

pale, cold, and naked,

bereft the jokes we used to share?

Though Charlotte Corday might be more likely to ask after her corpulus vagulus blandulus, from the sound of it."

Nora,

What an honor! An accomplished classicist arriving in one's humble private Limbo.

Can it be the touchstone dying verse of Hadrian, who, deprived the sudden mercy of a Charlotte Corday and thus forced to endure a "natural death," so providing succeeding millennia of poets this moving challenge, has finally met its English match in your lovely effort?

For those who are interested in the original, preserved as a fragment mentioned by an author of Hadrian's time (and one of the few documentary evidences of his inner or "personal" life):

ANIMULA VAGULA, BLANDULA,

HOSPES COMESQUE CORPORIS,

QUAE NUNC ABIDIS IN LOCA

PALLIDULA, RIGIDA, NUDULA,

NEC, UT SOLES. DABES IOCOS. . . .

P. AELIUS HADRIANUS, IMP.

Till now I believe the version of

'animula vagula, blandula' I've found most affecting was a prose attempt, in French, that of Marguerite Yourcenar in the overwhelming final passage of her novel

Memoirs of Hadrian. Here Hadrian, dying, has been brought to Baiae to be near the sea, where it is hoped his breathing will be improved; but the journey in the July heat has been an ordeal, and now the end is at hand. A small group of intimates surrounds him; gradually losing consciousness, he is however able to feel upon his fingers a friend's tender tears, reminding him through his pain that he "will have been loved in human wise." It is at this point in the magisterial fictional autobiography that M.Y. has Hadrian murmur, as if to himself, the bit that has become famous as

'animula vagula, blandula.' The English here is provided by M.Y. herself in collaboration with Grace Frick:

"Little soul, gentle and drifting, guest and companion of my body, now you will dwell below in pallid places, stark and bare; there you will abandon your play of yore. But one moment still, let us gaze together on these familiar shores, on these objects which doubtless we shall not see again... let us try, if we can, to enter death with open eyes."

Yourcenar was more than three decades at work on her Hadrian novel, beginning it as a young woman of twenty in 1924, destroying many early drafts as well as not a few later ones, abandoning it and returning and still returning as late as 1958 to add late reflections that are as much a part of the story of this very impersonal writer's work as Hadrian's lines are a part of his virtually unknown personal life--all we really have of it, in fact.

She notes, as of her first inklings that this Roman life might lead her into her own life as a writer, that "It did not take me very long to realize that I had embarked upon the life of a very great man. From that time on, still more respect for truth, closer attention, and, on my part, ever more silence."

In a wonderful essay called "Tone and Language in the Historical Novel," Yourcenar talks about the difficulty of fathoming intonations and inflections of speech across the darkness of lost centuries. Her remarks on building a "voice" for Hadrian are fascinating; they stress the enormous work--and risk--of invention and speculation that are every conscientious translator's burden. Documentary fragments remain to us, as she points out, but "Nothing, or virtually nothing, is left to us of those inflections, those quarter tones, those articulated half smiles which yet can change everything."

Therefore, she says, she chose, in her novel, "to make Hadrian use a dignified form of speech...[a] sustained style, half narrative, half meditative, but always essentially written..."

There have been many of the best English-speaking poets called to, and not a few probably also mysteriously chosen by, the Hadrian bit. The thing has a way of seeming to belong to everybody, young or old; we'll all be there one day.

John Donne, a compact version, 1611:

My little wandring sportful Soule,

Ghest, and companion of my body.

Henry Vaughan, 1652:

My soul, my pleasant soul and witty,

The ghest and consort of my body,

Into what place now all alone

Naked and sad wilt thou be gone?

No mirth, no wit, as heretofore,

Nor Jests wilt thou afford me more.

Matthew Prior, 1709:

My little, pretty, fluttering thing,

Must we no longer live together?

And dost thou prune thy trembling Wing,

To take thy Flight thou know'st not whither?

Thy humorous Vein, thy pleasing Folly

Lyes all neglected, all forgot;

And pensive, wav'ring, melancholy,

Thou dread'st and hop'st thou know not what.

Pope was talking about this little poem in public as early as the age of 23, in 1712, when he wrote a piece in The Spectator discussing "the famous Verses which the Emperor Adrian spoke on his death-bed," and offered a prose paraphrase. A year later he quoted the Hadrian lines in a letter to his friend Caryll, accompanied them with Prior's version, a translation of his own, and a "Christian" adaptation, and asked his friend which he thought the best. Not till eighteen years later did Pope publish the two poems he had done. Here is his translation:

Translated:

Adriani morientis ad Animam, OR, The Heathen to His departing Soul.

Ah! Fleeting Spirit! wand'ring Fire,

That long hast warm'd my tender Breast,

Must thou no more this Frame inspire?

No more a pleasing, chearful Guest?

Whither, ah whither art thou flying!

To what dark, undiscover'd Shore?

Thou seem'st all trembling, shiv'ring, dying,

And Wit and Humour are no more!

And then: George Gordon, Lord Byron, 1806:

Ah! gentle, fleeting, wav'ring sprite,

Friend and associate of this clay!

To what unknown region borne,

Wilt thou, now, wing thy distant flight?

No more, with wonted humour gay,

But pallid, cheerless, and forlorn.

And finally--three hundred years after Donne, two hundred after Keats, and a hundred and five after Byron--Ezra Pound, at the Hotel Eden in Sirmione, on the Lago di Garda (a site of "the original world of the gods," where, as Pound was delighted to know, Catullus had written his poetry), adding a nonce-word ("TENULLA") to the title, 1911:

"BLANDULA, TENULLA, VAGULA"

What hast thou, O my soul, with paradise?

Will we not rather, when our freedom's won,

Get us to some clear place where the sun

Lets drift in on us through the olive leaves

A liquid glory? If at Sirmio,

My soul, I meet thee, when this life's outrun...

And so on...rather hopefully on Pound's part of course, but that was still before the first Great War... down through the new Dark Ages to us, here and now. Where, Nora, it seems, from your marvelous version of Hadrian's poem, the breathing is better already.

And saying that, I am reminded of the brilliant compressed intensities a love of the classics like yours and Yourcenar's can kindle, warming the scene of the mind within the cold eternal night of the soul. Yourcenar left this astonishing account of her compositional attitude, during the writing of her novel -- which, she said, she completed in a state of "controlled delirium" that possessed her especially during a rail voyage across America:

"Closed inside my compartment as if in a cubicle of some Egyptian tomb, I worked late into the night between New York and Chicago; then all the next day, in the restaurant of a Chicago station where I awaited a train blocked by storms and snow; then again until dawn, alone in the observation car of a Santa Fe limited, surrounded by black spurs of the Colorado mountains, and by the eternal patterns of the stars. Thus were written at a single impulsion the passages on food, love, sleep, and the knowledge of men. I can hardly recall a day spent with more ardor, or more lucid nights."

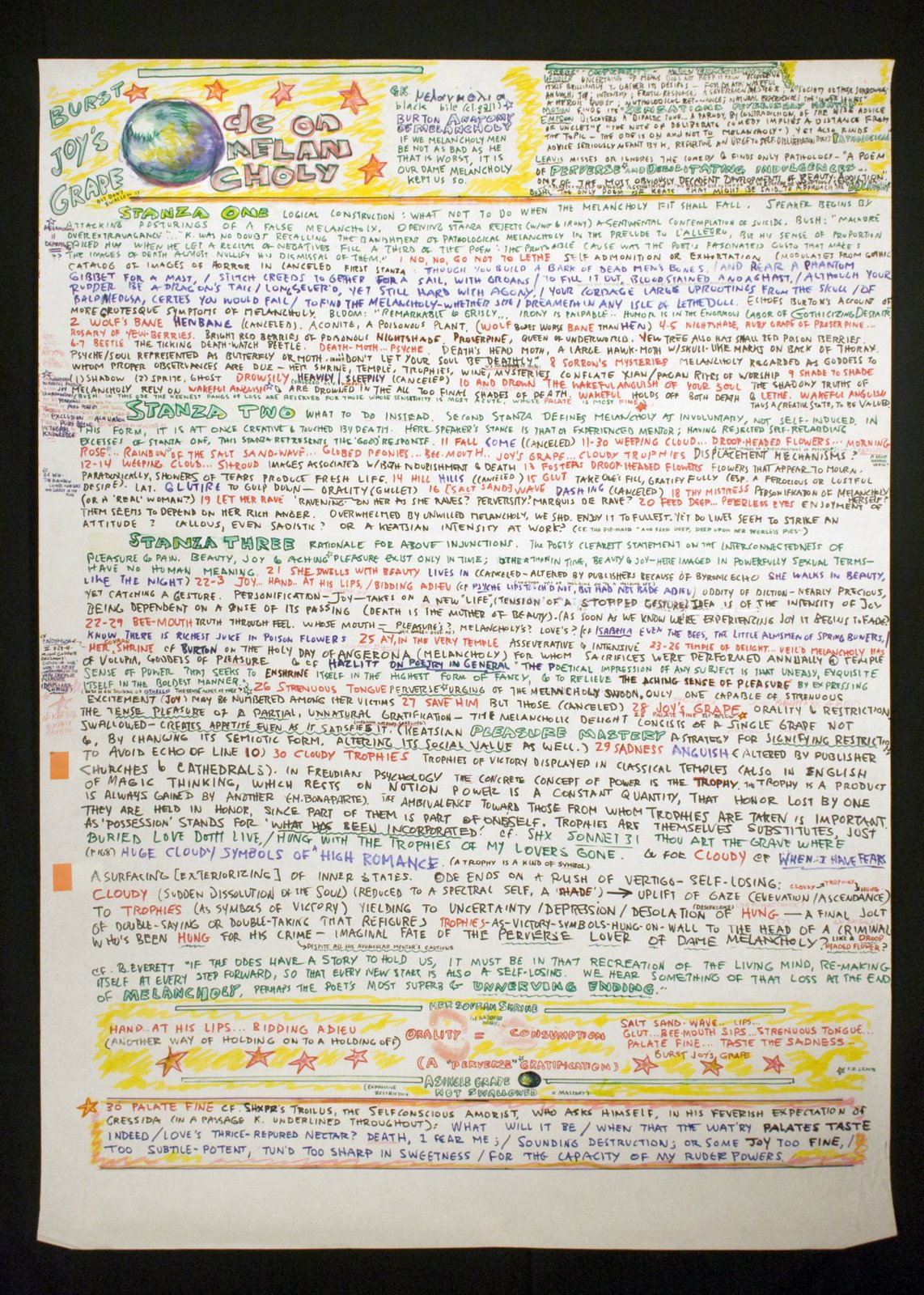

The Bay of Baiae, with Apollo and Sibyl: Joseph Mallord William Turner, 1823 (Tate Gallery)

The Bay of Baiae, with Apollo and Sibyl: Joseph Mallord William Turner, 1823 (Tate Gallery)