.

Samuel Johnson on Measure for Measure

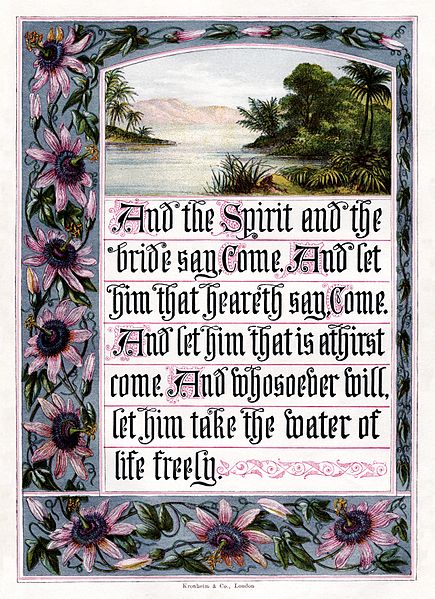

III.i.14 (63,3) [For all the accommodations, that thou bear'st Are nurs'd by baseness] Dr. Warburton is undoubtedly mistaken in supposing that by baseness is meant self-love here assigned as the motive of all human actions. Shakespeare only meant to observe, that a minute analysis of life at once destroys that splendour which dazzles the imagination. Whatever grandeur can display, or luxury enjoy, is procured by baseness, by offices of which the mind shrinks from the contemplation. All the delicacies of the table may be traced back to the shambles and the dunghill, all magnificence of building was hewn from the quarry, and all the pomp of ornaments dug from among the damps and darkness of the mine.

James Buchan on Money

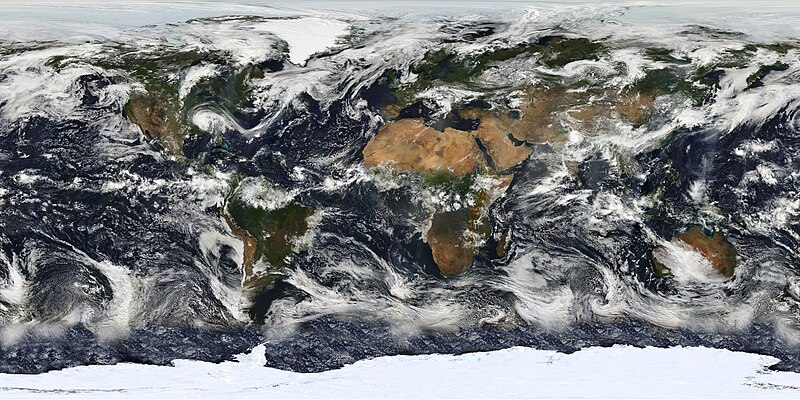

Americans, as Santayana noted, prefer to talk of quantities rather than qualities and are therefore apt to consider things and actions in terms of money quantities. The great diversion of United States life -- and the force that runs through U.S. history, and makes it intelligible... -- is speculation in real estate: that is, the conversion of Eden into money. It was the force behind the great movements westward, where pioneers sold out their homesteads at immense premiums to a timid second generation; then, when the coast was reached, there was money to be made in swampland in Florida in the 1920s, in subdivided farmland in the 1950s and 1960s and, in the 1980s, in shoreland reclaimed from the sea.

*

For money to serve you, you must believe in it; if you doubt it a moment, it vanishes, like a ghost. What happened at the turn of the 1930s was that Americans lost faith in money. People stopped borrowing and bankers stopped lending... Most [Americans] felt quite helpless. Because they had believed that the markets of the 1920s were real, when those broke it seemed to Americans that reality had been turned upside down: that the snow of the 1929 winter, in Fitzgerald's formulation, was somehow of a different order because it was wet and cold and nobody swept it away, because, in short, money couldn't make it vanish.

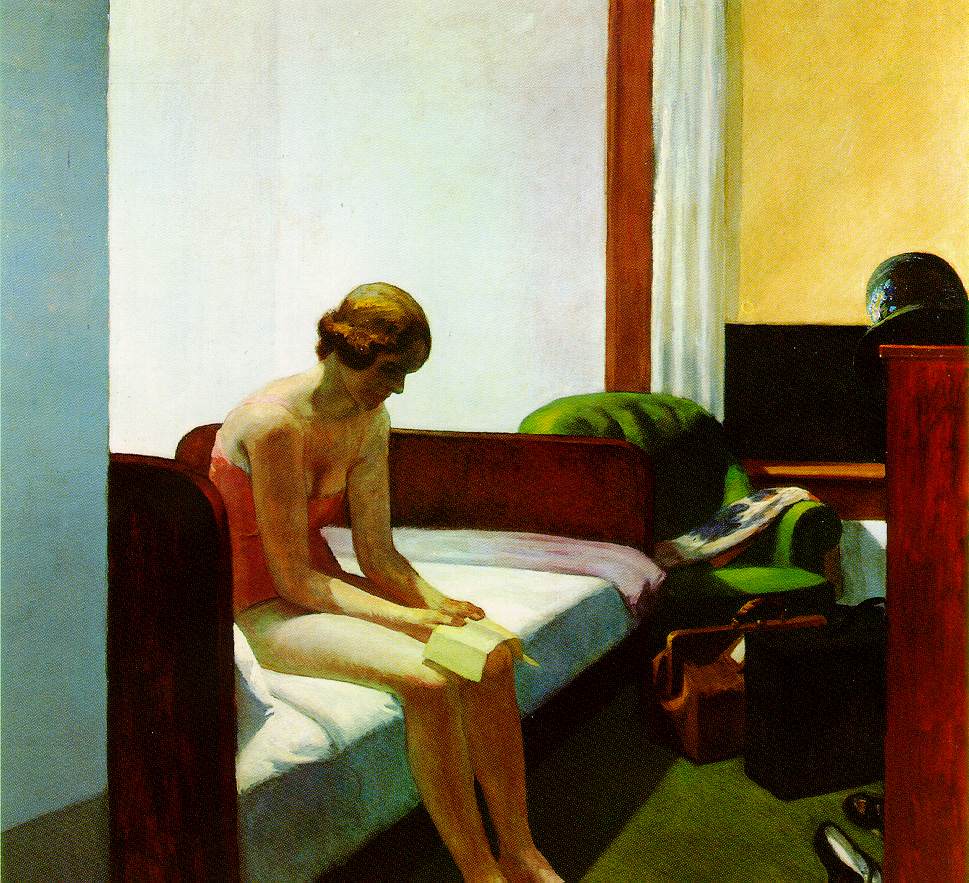

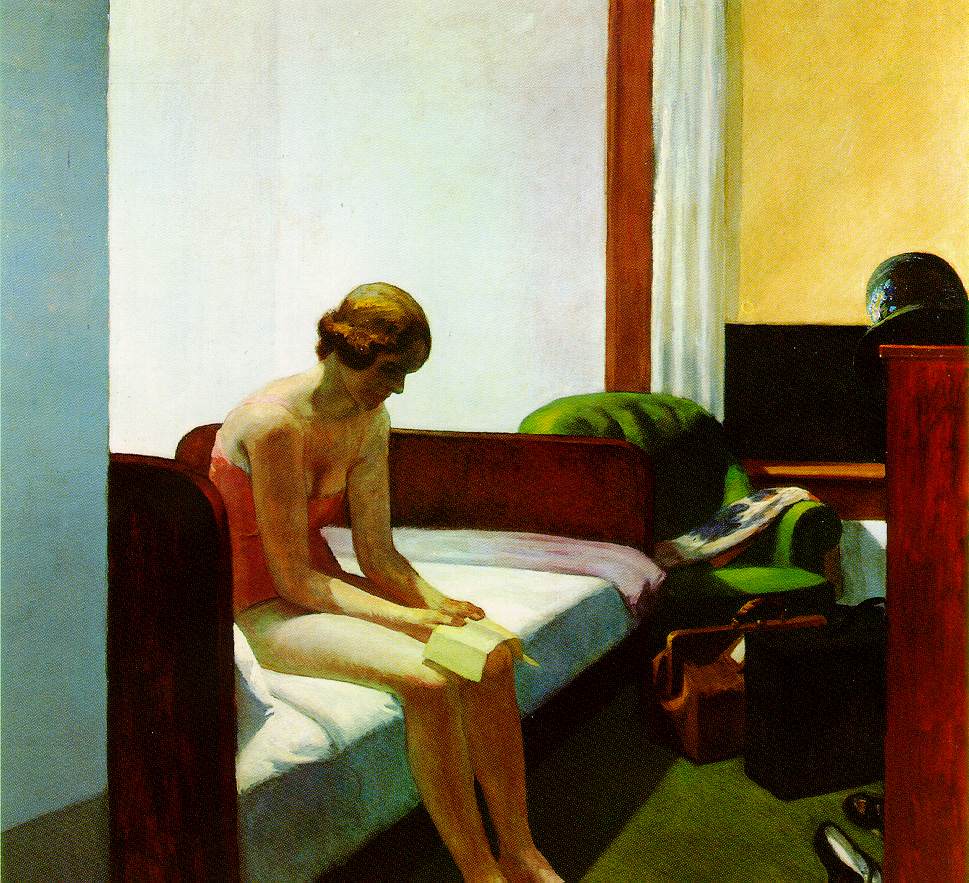

Reality was suddenly transformed, not just in the market indices but in the hard, sensuous world that had been forgotten, which was now a world of street corners and ruined family farms and busted banks and men walking from town to town shooting vermin for food. In that transfiguration --- the moment so prized by the Greek tragedians in which the hero recognises that he has been made mad -- things stood out in hard, unyielding concreteness. Corporations emerged from behind their stock symbols as cold furnaces and shuttered gates; bank presidents made grovelling fools of themselves before government committees; crowds dissipated into lonely, struggling individuals. In certain of Hopper's paintings of that period Americans are shown in a cold, mute isolation, squatters in their own civilisation. A little drawing in a gallery I saw on Madison Avenue, two zeroes to represent the tops of gasoline pumps, three undulating lines to show the telephone wires loping away into infinity, a squiggle that represents the open bonnet of a Ford, still fills me with the sensation of a desperate, pointless flight. It is the definition for me of the antique conception of panic.

Samuel Johnson: Notes on Shakespeare, 1765

James Buchan: Frozen Desire: The Meaning of Money, 1997

Paintings by Edward Hopper:

Approaching a City, 1946 (The Phillips Collection)

New York Movie, 1939 (Museum of Modern Art, New York)

Hotel Room, 1931 (Fondation Thyssen-Bornemisza)