.

Untitled (Dodge, Alameda, California): photo by Christopher Hall (Dead Slow), 16 January 2009

Samuel Beckett on involuntary memory

The most successful evocative experiment can only project

the echo of a past sensation, because, being an act of intellection, it

is conditioned by the prejudices of the intelligence which abstracts

from any given sensation, as being illogical and insignificant, a

discordant and frivolous intruder, whatever word or gesture, sound or

perfume, cannot be fitted into the puzzle of a concept. But the essence

of any new experience is contained precisely in this mysterious element

that the vigilant will reject as an anachronism. It is the axis about

which the sensation pivots, the centre of gravity of its coherence. So

that no amount of voluntary manipulation can reconstitute in its

integrity an impression that the will has–so to speak–buckled into

incoherence. But if, by accident, and given favourable

circumstances (a relaxation of the subject’s habit of thought and a

reduction of the radius of his memory, a generally diminished tension of

consciousness following upon a phase of extreme discouragement), if by

some miracle of analogy the central impression of a past sensation

recurs as an immediate stimulus which can be instinctively identified by

the subject with the model of duplication (whose integral purity has been retained because it has been forgotten),

then the total past sensation, not its echo nor its copy, but the

sensation itself, annihilating every spatial and temporal restriction,

comes in a rush to engulf the subject in all the beauty of its

infallible proportion.

The most trivial experience -- he says in effect -- is encrusted with

elements that logically are not related to it and have consequently been

rejected by our intelligence: it is imprisoned in a vase filled with

a certain perfume and a certain colour and raised to a certain

temperature. These vases are suspended along the height of our years,

and, not being accessible to our intelligent memory, are in a sense

immune, the purity of their climatic content is guaranteed by

forgetfulness, each one is kept at its distance, at its date. So that

when the imprisoned microcosm is besieged in the manner described, we

are flooded by a new air and a new perfume (new precisely because

already experienced), and we breathe the true air of Paradise, of the

only Paradise that is not the dream of a madman, the Paradise that has

been lost.

But if this mystical experience communicates an extratemporal

essence, it follows that the communicant is for the moment an

extratemporal being. Consequently the Proustian solution consists, in so

far as it has been examined, in the negation of Time and Death, the

negation of Death because the negation of Time. Death is dead because

Time is dead. (At this point a brief impertinence, which consists in

considering Le Temps Retrouvé almost as inappropriate a description of the Proustian solution as Crime and Punishment

of a masterpiece that contains no allusion to either crime or

punishment. Time is not recovered, it is obliterated. Time is recovered,

and Death with it, when he leaves the library and joins the guests,

perched in precarious decrepitude on the aspiring stilts of the former

and preserved from the latter by a miracle of terrified equilibrium. If

the title is a good title the scene in the library is an anticlimax.)

Samuel Beckett: from Proust (1931)

Boat (Cadillac, San Francisco, California): photo by Christopher Hall (Dead Slow), 23 October 2008

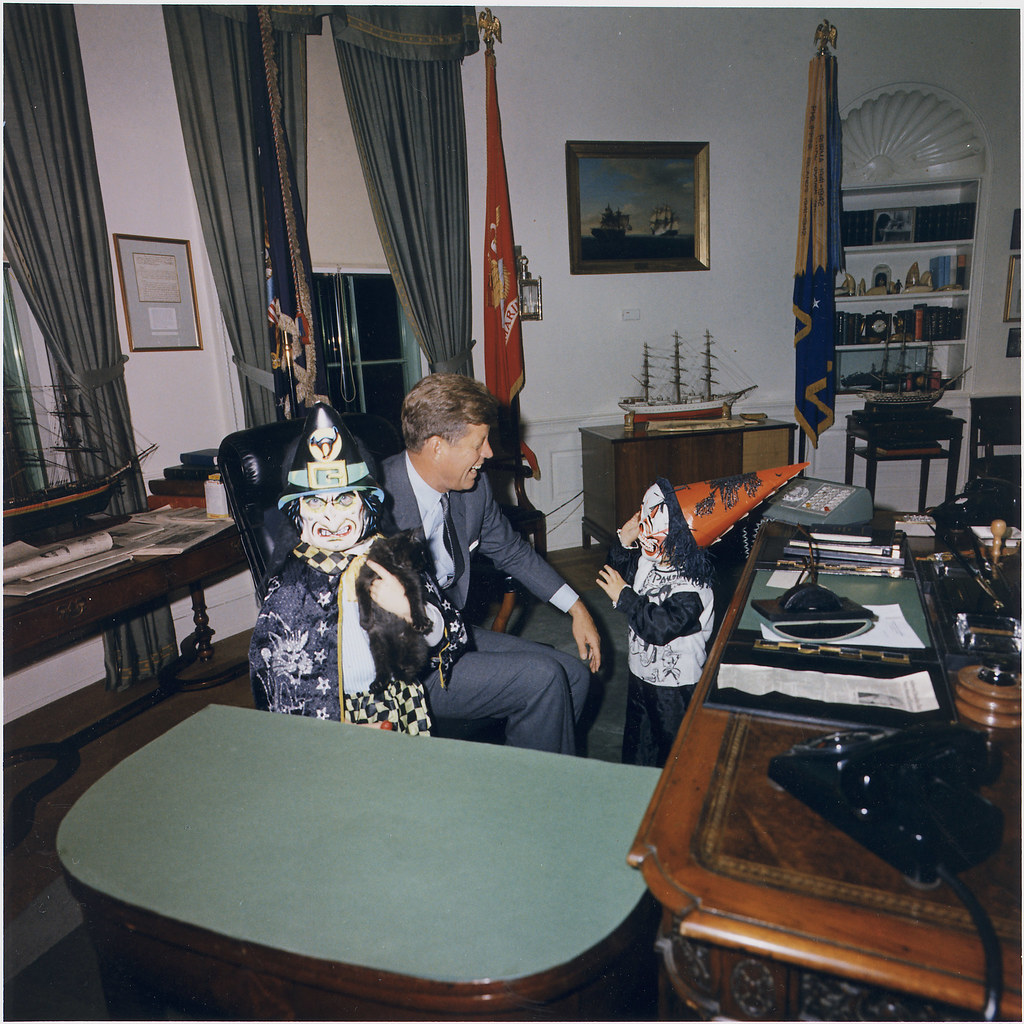

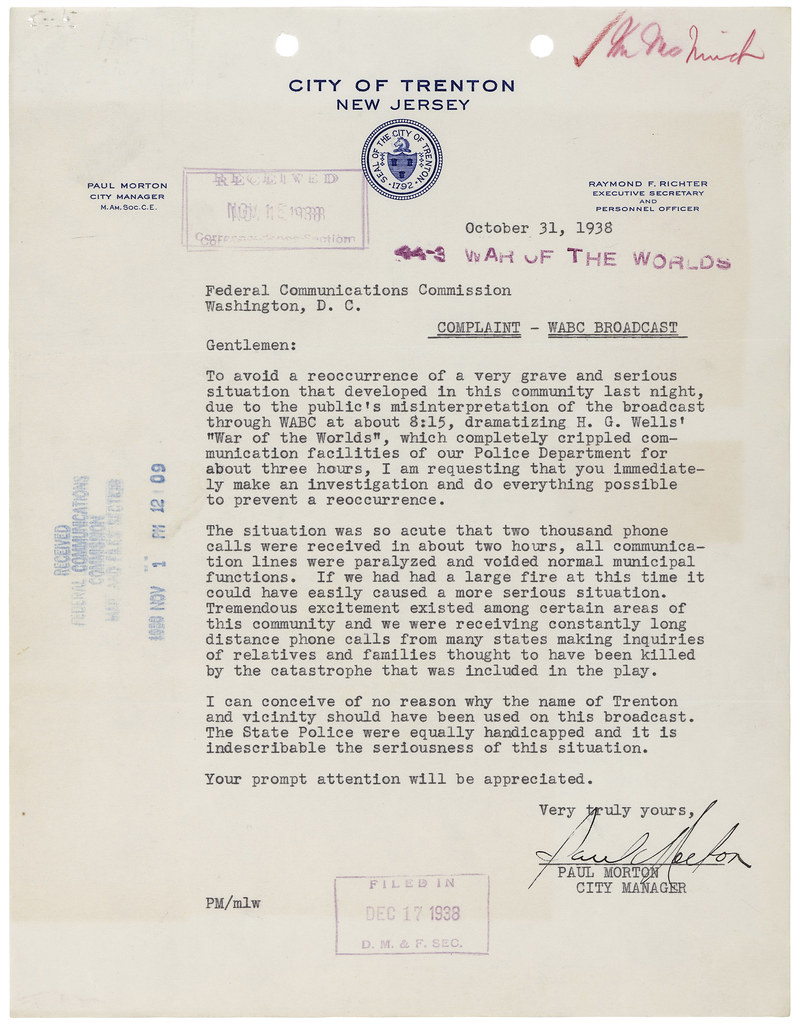

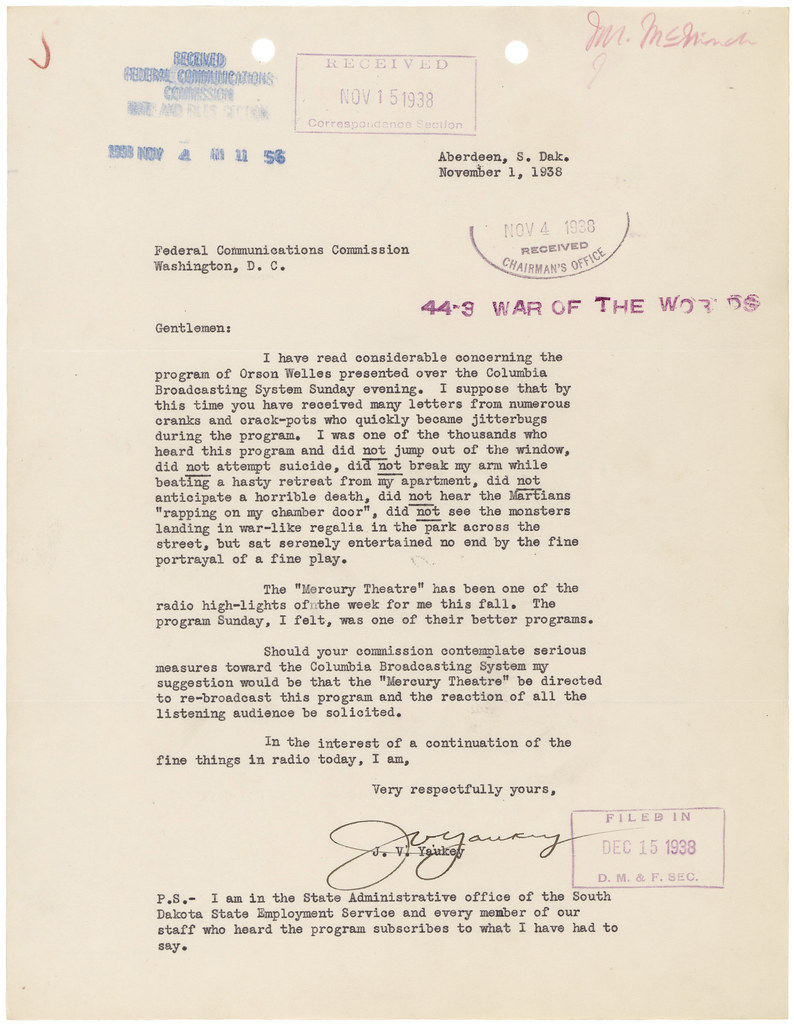

From an interview with photographer Christopher Hall

I find your work to be almost instantly recognizable by the

tones, mood, and atmosphere of your shots. Was this a sort of vision

you worked to achieve or is it more natural than intentional?

I think it was a happy accidental discovery, which I now doggedly

pursue. I prefer the muted light you get on overcast days, and it’s a

look that comes through in most of my photos. I almost always wish for

gloomy weather. When it comes to photography, I’ll usually just stay

home if it’s bright and sunny outside.

A large percentage of your work is focused on the automobile

and its place in our environment. At some point was that direction a

conscious decision?

I think the automobile really defines the American way of life. For

better or worse, our entire country has been (re-)designed for the

benefit of the automobile driver. On the one hand, the strip malls you

used to find in so many places were such horrific creations, yet they

were a by-product of the suburban neighborhoods I grew up in and where I

felt so safe during my childhood. Eventually, the strip malls were

bulldozed so they could build an enormous Wal-Mart, with a huge parking

lot where you can park your car while you buy stuff. That’s probably a

good starting point for understanding the love/hate relationship I have

with the automobile.

I have noticed in comments you have made, that the automobile

itself is not particularly a point of passion for you, yet you seem to

use it as a starting point for something larger – as if it becomes an

ingredient for something more telling. Could you comment on that?

Well, I think the car is a key ingredient in the casserole, but I

don’t really see my photos as being just about a car. That’s really

secondary. The scenes are all “found,” never arranged, but I like taking

an approach to composition that helps make things seem just a bit

implausible. Sometimes it’s because everything seems trapped in a time

capsule -- in others, there’s some unbelievable color coordination

happening that people suspect is staged. I like that my photos can

convey the idea that things aren’t quite what they seem. There’s also a

good deal of processing childhood memories involved. I had a happy

childhood in the suburbs, and everything seemed perfect to me at the

time. Dad went to work, Mom was a housewife, there were always meals on

the table, and I spent my days in school with the other kids. But the

60′s really weren’t that happy when you think about it. The Civil Rights

movement was a source of tremendous turmoil; we were bogged down in a

war in Vietnam; tensions were often high because of the Cold War; and

one assassination followed another. But there we were, enjoying our

happy life in the suburbs, and gas cost 34 cents a gallon.

I think my photos mourn a place that probably never really existed,

except in my own mind. Everything was fine, but only because I wasn’t

old enough to know better. There are traces of that time that you can

find even now, if you look hard enough. But was it really the way you

remember? Did it even exist?

Christopher Hall, from an interview in American Elegy, 1 May 2011

Untitled (Chevrolet, Alameda, California): photo by Christopher Hall (Dead Slow), 25 October 2008

Untitled (Chevrolet, Alameda, California): photo by Christopher Hall (Dead Slow), 25 October 2008

Odd Fellow (Dodge Dart Swinger, Vallejo, California): photo by Christopher Hall (Dead Slow), 9 December 2008

West End Town (Alameda, California): photo by Christopher Hall (Dead Slow), 2 February 2010

Untitled (Ford Thunderbird, Berkeley, California). While I was shooting this, a neighbor came out and told me about the

car. It's owned by Miss Ruthie Witherspoon, who bought it new in 1956

and has been driving it ever since. That's Miss Witherspoon's house in

the background, too: photo by Christopher Hall (Dead Slow), 10 February 2010

Untitled (Ford, Oakland, California): photo by Christopher Hall (Dead Slow), 19 February 2010

Everything's gone green (Camaro and Lincoln, Oakland, California): photo by Christopher Hall (Dead Slow), 24 March 2010

Untitled (Oakland, California): photo by Christopher Hall (Dead Slow), 28 March 2010

Untitled (Plymouth, Oakland, California): photo by Christopher Hall (Dead Slow), 1 April 2010

Untitled (AMC Ambassador Wagon, West Oakland, California): photo by Christopher Hall (Dead Slow), 20 May 2010

Curtis and Addison Streets, Berkeley: photo by Christopher Hall (Dead Slow), 15 August 2010

Untitled (Saab, San Francisco, California): photo by Christopher Hall (Dead Slow), 23 September 2010

Untitled (16th Street, San Francisco, California): photo by Christopher Hall (Dead Slow), 5 November 2010

Untitled (Volvo, San Francisco, California): photo by Christopher Hall (Dead Slow), 28 December 2010

Untitled (Potrero Hill, San Francisco, California): photo by Christopher Hall (Dead Slow), 1 May 2011

Untitled (Cadillac, Alameda, California): photo by Christopher Hall (Dead Slow), 1 May 2011

Untitled (Ford Falcon, Emeryville, California): photo by Christopher Hall (Dead Slow), 8 December 2011

Florida Street (VW Bus, Mission District, San Francisco, California): photo by Christopher Hall (Dead Slow), 21 January 2012

Untitled (Ford Thunderbird, San Francisco, California): photo by Christopher Hall (Dead Slow), 22 January 2012

Untitled (Plymouth, San Francisco, California): photo by Christopher Hall (Dead Slow), 3 February 2012

Untitled (Ford Galazie 500, Alameda, California): photo by

Christopher Hall (Dead Slow), 12 February 2012

Union and Jones (San Francisco, California): photo by Christopher Hall (Dead Slow), 7 June 2012

Union and Jones (San Francisco, California): photo by Christopher Hall (Dead Slow), 7 June 2012

Untitled (Lincoln Continental, San Francisco, California): photo by Christopher Hall (Dead Slow), 14 December 2012

Untitled (Richmond, California): photo by Christopher Hall (Dead Slow), 21 January 2013

Untitled (International Travelall, Alameda, California): photo by

Christopher Hall (Dead Slow), 8 February 2013

Untitled (Berkeley, California): photo by Christopher Hall (Dead Slow), 2 May 2013

Untitled (Ford Falcon, Alameda, California): photo by Christopher Hall (Dead Slow), 2 September 2013

Untitled (San Francisco, California): photo by Christopher Hall (Dead Slow), 9 August 2012