On a steep, gardenia-scented street in the north-eastern Athens

suburb of Gerakas, in one corner of a patch of bare ground, stands a

small caravan.

Plastic mesh fencing –- orange, of the kind builders use –- encloses a

neat garden in which peppers, courgettes, lettuces and beans grow in

well-tended raised beds. Flowers, too.

The caravan is old, but spotless. It is home to Georgios

Karvouniaris, 61, and his sister Barbara, 64, two Greeks for whom all

the Brussels wrangling over VAT rates, corporation tax and pension

reforms has meant nothing -- because they have nothing, no income of any

kind.

Next Sunday’s referendum -- which, if the country stays solvent that long, will either send Greece

back to the negotiating table with its creditors or precipitate its

exit from the eurozone -- is unlikely to affect them much either.

“I do not see how any of it will change our lives. I have no hope,

anyway,” said Georgios, sitting in a scavenged plastic garden chair

beneath a parasol liberated from a skip.

After seven years of a crisis that has left 26% of Greece’s workforce

unemployed, 30% of its people below the poverty line, 17% unable to

meet their daily food needs and 3.1 million without health insurance, it

is hard to see how anything decided in Brussels or in Athens in the

coming week will do much to change the lives of a large number of Greeks

any time soon.

“Those that were already on the margins have been pushed right to the

very, very edge, and those who were in the middle have been pushed to

the margins,” said Ioanna Pertsinidou of Praksis, a charity that runs

day centres for vulnerable people and offers legal and employment

advice.

“So

many people – ordinary, low-to-middle income people with jobs and homes

and their lives on track -- have seen their lives go drown the drain so

fast,” Pertsinidou said. “People who never dreamed that one day they

would not be able to pay their electricity bill, or feed their children

properly.”

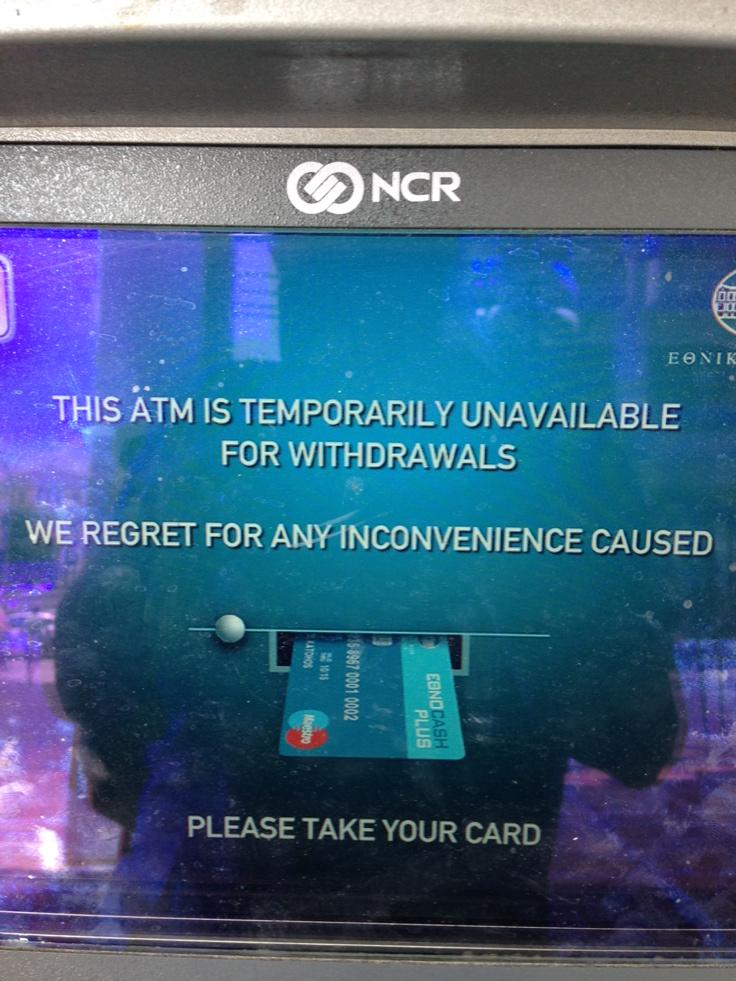

As it has scrabbled for every last cent to satisfy its creditors and

ward off bankruptcy, Greece’s government has taken cash wherever it

could -- local authorities, healthcare, pensions, social services have

all been tapped. In a country of 11 million people, public spending is

now €65bn (£45.6bn) less than it was in 2010. “There is no safety net

left,” said Pertsinidou.

No one need tell that to the Karvouniaris family. Georgios is a stern

man, still strong, smartly shaven and dressed in a clean green polo

short and jeans. His sister, remarkably jovial, wears black for their

younger brother Vangelis, who died of nobody will say exactly what two

years ago next month, aged 52. He spent a brief week in hospital before

his death, for which his siblings recently received a €2,000 bill --

which they managed to get written off.

Until March 2013, the three lived in an apartment a mile or so away

that they had shared since 1980. None of them had ever married. It

worked well. Georgios, a welder and mechanic before becoming a bank

security guard, and Vangelis, a salesman, shoe repairer and, latterly,

gardener, were the breadwinners. Barbara cooked, cleaned and looked

after her brothers.

Quite early in Greece’s crisis, Vangelis lost his job. Then in

February 2011, Georgios lost his at the Agrotiki bank, where he had

worked for 12 years. After leaving school at 12 and working ever since,

Georgios got €465 unemployment benefit for eight months, then €200 for a

year, then nothing.

The rent on the apartment was €250. “We spent all we had,” he said.

“Our savings. We sold Barbara’s jewellery, for half its worth. We tried

to sell this patch of land but no one would buy it. For the first time

in 30 years, we didn’t pay our rent. By the end we couldn’t even afford

food.”

If the Karvouniarises are not now sleeping rough, it is because a

neighbour saw them sitting in tears outside their apartment building,

formally threatened with eviction and all packed up but with nowhere to

go. They had not eaten for three days.

It took time, but Despina Moragianis -- a relative of that neighbour --

and her friends, Ann Papastavrou and Niki Festas, women in their 60s,

rallied their women’s group in Halandri.

Twenty-odd people, none wealthy, pitched in to buy the 15-year-old

caravan, which was towed to the Kourvaniaris family’s small plot, once

intended as Barbara’s dowry.

For 13 months there was no water, but a campaign by the women

persuaded the Gerakas town hall to fit a standpipe in May last year.

Later, the group raised €1,000 to have it plumbed into the caravan and a

septic tank dug, so the toilet works. The next target is a solar panel

for electricity.

Georgios Karvouniaris and his sister Barbara outside their caravan: photo by Jon Henley for The Guardian, 28 June 2015

Every month the group holds a raffle, the proceeds of which buy fresh

fruit and vegetables -- apples, oranges, beans, potatoes -- which

Moragianis and her friends bring up to the caravan once a week. Fresh

meat is once a week. Non-perishables -- spaghetti, rice, flour, condensed

milk, tomato sauce -- come from the food bank.

And so the Karvouniaris siblings survive. Georgios digs, recycles

what he can find on the streets, takes long walks and dreams of fresh

milk. No electricity means no fridge. Barbara cooks – there is a gas

stove – cleans, washes clothes and tends her garden.

The couple have no money -- a friendly town hall official paid their

latest €18 water bill out of his own pocket -- and no hope of any until

Georgios qualifies for his pension at 67. “I’d hoped it might be 65, in

four years’ time, but they’ve just recently decided to raise the age

limit,” he said.

He is not sure how much he will get even then. Pensions have been a

major stumbling block in Greece’s aid-for-reforms talks with its

creditors, who want further savings from a system whose benefits have

already been cut by 45%, leaving nearly half of Greece’s pensioners

below the monthly poverty threshold of €665.

It is not just pensioners in penury. Under a limited relief programme

promised by the Syriza party during its election victory in January,

more than 300,000 of the poorest Greek households applied last month for

food aid, a small rent allowance and to have their electricity

reconnected for free.

So far the government has found the money to pay a small housing

benefit to precisely 1,073 people, the social solidarity minister,

Theano Fotiou, admitted. The €70 a month grocery voucher Georgios and

Barbara were promised under the scheme -- “We have no house and no power,

so there was nothing else we qualified for,” said Georgios -- has yet to

materialise.

Barbara’s face briefly clouds. How does she feel about the way they

have been treated? “Disgusted,” she said, quietly. “Just … disgusted.”

She smiles again. “But we’ve been lucky. There are people who have

nowhere to sleep at all.”

According to a University of Crete study earlier this year, there are

now 17,700 people without proper and secure housing in Athens alone.

Some sleep rough or in cars, others camp with friends or relatives, or

live in squats and hostels.

A majority are in their own homes, threatened with imminent eviction

because they are among the estimated 320,000 Greek families who have

fallen behind with a mortgage or other payment to their bank.

Two are in a small donated caravan, living on food donated by a group

of Greek women. Georgios is grateful, but he also gets angry sometimes.

“I have worked all my life. I’ve paid my taxes all my life,” he said.

“I’m 61 years old and if it wasn’t for the generosity of people who

three years ago we had never met, we would be sleeping on a bench. You

do what you can. But it doesn’t seem right.”

#GreeceCrisis Graffiti and people in the streets in Athens on June 28, 2015. #AFP PHOTO by @ArisMessinis: image via Aurelia BAILLY @Aurelia BAILLY, 28 June 2015