[Untitled]: photo by Tonatiuh Cabello, 4 March 2017

You have to dive down, as it were,

and sink more rapidly

than that which sinks in advance of you.

A boy peeks out of the window of his house in Nuevo Laredo, Tamaulipas state, Mexico, across the border from Laredo in the U.S, on Friday: photo by Rodrigo Abd/AP, 24 March 2017

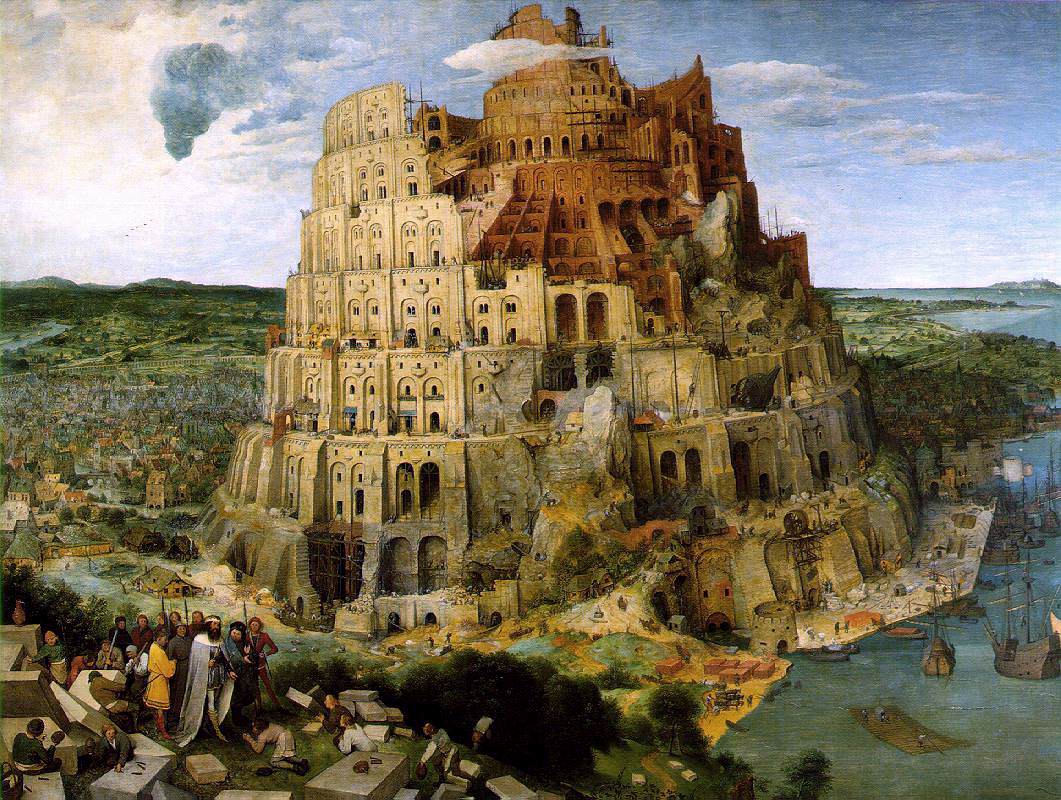

The Tower of Babel (detail): Pieter Bruegel the Elder, 1563, oil on oak panel (Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna)

_MG_2195: photo by Filiberto Morales, 18 February 2017

_MG_2195: photo by Filiberto Morales, 18 February 2017

_MG_2195: photo by Filiberto Morales, 18 February 2017

The Tower of Babel (detail): Pieter Bruegel the Elder, 1563, oil on oak panel (Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna)

The Tower of Babel (detail): Pieter Bruegel the Elder, 1563, oil on oak panel (Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna)

_MG_1674: photo by Filiberto Morales, 4 February 2017

_MG_1674: photo by Filiberto Morales, 4 February 2017

_MG_1674: photo by Filiberto Morales, 4 February 2017

The Tower of Babel (detail): Pieter Bruegel the Elder, 1563, oil on oak panel (Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna)

The Tower of Babel (detail): Pieter Bruegel the Elder, 1563, oil on oak panel (Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna)

Great Wall at Mutianyu. The great wall - not yet reconstructed.: photo by niragag, 7 February 2011

Great Wall at Mutianyu. The great wall - not yet reconstructed.: photo by niragag, 7 February 2011

Great Wall at Mutianyu. The great wall - not yet reconstructed.: photo by niragag, 7 February 2011

The Construction of the Tower of Babel (The "little" Tower of Babel): Pieter Bruegel the Elder, c. 1563 (Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen, Rotterdam)

The Construction of the Tower of Babel (The "little" Tower of Babel): Pieter Bruegel the Elder, c. 1563 (Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen, Rotterdam

The Construction of the Tower of Babel (The "little" Tower of Babel) (detail): Pieter Bruegel the Elder, c. 1563 (Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen, Rotterdam

The Construction of the Tower of Babel (The "little" Tower of Babel) (detail): Pieter Bruegel the Elder, c. 1563 (Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen, Rotterdam

Franz Kafka: The Great Wall of China

The Tower of Babel: Pieter Bruegel the Elder, 1563 (Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna)

First,

it has to be said that achievements were brought to fruition at that

time which rank slightly behind the Tower of Babel, although in the

pleasure they gave to God, at least by human reckoning, they made an

impression exactly the opposite of that structure. I mention this

because at the time construction was beginning a scholar wrote a book

in which he drew this comparison very precisely. In it he tried to show

that the Tower of Babel had failed to attain its goal not at all for

the reasons commonly asserted, or at least that the most important

causes were not among these well-known ones. He not only based his

proofs on texts and reports, but also claimed to have carried out

personal inspections of the location and thus to have found that the

structure collapsed and had to collapse because of the weakness of its

foundation. And it is true that in this respect our age was far

superior to that one long ago. Almost every educated person in our age

was a mason by profession and infallible when it came to the business of

laying foundations. But it was not at all the scholar’s aim to prove

this. Instead he claimed that the great wall alone would for the first

time in the age of human beings create a secure foundation for a new

Tower of Babel. So first the wall and then the tower. In

those days the book was in everyone’s hands, but I confess that even

today I do not understand exactly how he imagined this tower. How could

the wall, which never once took the form of a circle but only a sort

of quarter or half circle, provide the foundation for a tower? But it

could be meant only in a spiritual sense. But then why the wall, which

was something real, a product of the efforts and lives of hundreds of

thousands of people? And why were there plans in the book—admittedly

hazy plans—sketching the tower, as well as detailed proposals about how

the energies of the people could be strictly channeled into the new

work in the future?

The Construction of the Tower of Babel (The "little" Tower of Babel), detail: Pieter Bruegel the Elder, c. 1563 (Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen, Rotterdam)

There

was a great deal of mental confusion at the time—this book is only one

example—perhaps for the simple reason that so many people were trying

as hard as they could to join together for a single purpose. Human

nature, which is fundamentally careless and by nature like the whirling

dust, endures no restraint. If

it restricts itself, it will soon begin to shake the restraints madly

and tear up walls, chains, and even itself in every direction.

[Untitled]: photo by Tonatiuh Cabello, 22 September 2015

[Untitled]: photo by Tonatiuh Cabello, 22 September 2015

It

is possible that even these considerations, which argued against

building the wall in the first place, were not ignored by the

leadership when they decided on piecemeal construction. We—and here I’m

really speaking on behalf of many—actually first found out about it by

spelling out the orders from the highest levels of management and

learned for ourselves that without the leadership neither our school

learning nor our human understanding would have been adequate for the

small position we had within the enormous totality. In the office of

the leadership—where it was and who sat there no one I asked knows or

knew—in this office I imagine that all human thoughts and wishes revolve

in a circle, and all human aims and fulfillments in a circle going in

the opposite direction. But through the window the reflection of the

divine worlds fell onto the hands of the leadership as they drew up the

plans.

The Construction of the Tower of Babel (The "little" Tower of Babel), detail: Pieter Bruegel the Elder, c. 1563 (Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen, Rotterdam)

And

for this reason the incorruptible observer will reject the notion that

if the leadership had seriously wanted a continuous construction of

the wall, they would not have been able to overcome the difficulties

standing in the way. So the only conclusion left is that the leadership

deliberately chose piecemeal construction. But building in sections

was something merely makeshift and impractical. So the conclusion

remains that the leadership wanted something impractical. An odd

conclusion! True enough, and yet from another perspective it had some

inherent justification. Nowadays one can perhaps speak about it without

danger. At that time for many people, even the best, there was a secret

principle: Try with all your powers to understand the orders of the

leadership, but only up to a certain limit—then stop thinking about

them. A very reasonable principle, which incidentally found an even

wider interpretation in a later often repeated comparison:

Stop further thinking, not because it could harm you—it is not at all

certain that it will harm you. In this matter one cannot speak in

general about harming or not harming. What will happen to you is like a

river in spring. It rises, grows stronger, eats away more powerfully

at the land along its banks, and still maintains its own course down to

the sea and is more welcome as a fitter partner for the sea. Reflect

upon the orders of the leadership as far as that. But then the river

overflows its banks, loses its form and shape, slows down its forward

movement, tries, contrary to its destiny, to form small seas inland,

damages the fields, and yet cannot maintain its expansion long, but

runs back within its banks, in fact, even dries up miserably in the hot

time of year which follows. Do not reflect on the orders of the

leadership to that extent.

![[Cn1202-03.jpg]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEhqDenj5zWCzlesHxwy3lVpd9NMvxX3xLH1Q5e1j-H80dElGkpuoQ46gBB9fm9SHUQ7VpYHHKJb1Ce2bbctMSj7UAOqXscfhdP6sy51JQsrbqihffBZR4A4z8UUuvzsa8od6UD11dfZ2So/s1600/Cn1202-03.jpg)

The first turn of the Yangtze, at Shigu, Yunnan Province: photo by Jialiang Gao, 2003

Now,

this comparison may perhaps have been extraordinarily apt during the

construction of the wall, but it has at least only a limited relevance

to my present report. For my investigation is merely historical. There

is no lightning strike flashing any more from storm clouds which have

long since vanished, and thus I may seek an explanation for the

piecemeal construction which goes further than the one people were

satisfied with back then. The limits which my

ability to think sets for me are certainly narrow enough, but the

region one would have to pass through here is endless.

The Tower of Babel (detail): Pieter Bruegel the Elder, 1563, oil on oak panel (Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna)

Against whom was the great wall to provide protection? Against the people of the north. I

come from south-east China. No northern people can threaten us there.

We read about them in the books of the ancients. The atrocities which

their nature prompts them to commit make us heave a sigh on our

peaceful porches. In the faithfully accurate pictures of artists we see

these faces of damnation, with their mouths flung open, the sharp

pointed teeth stuck in their jaws, their straining eyes, which seem to

be squinting for someone to seize, someone their jaws will crush and

rip to pieces. When children are naughty, we hold up these pictures in

front of them, and they immediately burst into tears and run into our

arms. But we know nothing else about these northern lands. We have never

seen them, and if we remain in our village, we never will see them,

even if they charge straight at us and hunt us on their wild horses.

The land is so huge, it would not permit them to reach us, and they

would lose themselves in the empty air.

The Construction of the Tower of Babel (The "little" Tower of Babel), detail: Pieter Bruegel the Elder, c. 1563 (Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen, Rotterdam)

So

if things are like this, why do we leave our homeland, the river and

bridges, our mothers and fathers, our crying wives, our children in

need of education, and go away to school in the distant city, with our

thoughts on the wall to the north, even further away? Why? Ask the

leadership. They know us. As they mull over their immense concerns,

they know about us, understand our small worries, see us all sitting

together in our humble huts, and approve or disapprove of the prayer

which the father of the house says in the evening in the circle of his

family. And if I may be permitted such ideas about the leadership, then I

must say that in my view the leadership existed even earlier. It did

not come together like some high mandarins quickly summoned to a

meeting by a beautiful dream of the future, something hastily

concluded, a meeting which by evening saw to it that the general

population was driven from their beds by a knocking on the door so that

they could carry out the decision, even if it was only to set up a

lantern in honour of a god who had shown favour to the masters the day

before, so that he could thrash them in some dark corner the next day,

when the lantern had only just died out. On the contrary, I imagine the

leadership has existed since time immemorial, along with the decision

to construct the wall as well. Innocent northern people believed they

were the cause; the admirable and innocent emperor believed he had

given orders for it. We who were builders of the wall know otherwise

and are silent.

The Tower of Babel (detail): Pieter Bruegel the Elder, 1563, oil on oak panel (Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna)

Even back then during the construction of the wall and afterwards, right up to the present day, I have devoted myself almost exclusively to the histories of different people. There are certain questions for which one can, to some extent, get to the heart of the matter only in this way. Using this method I have found that we Chinese possess certain popular and state institutions which are uniquely clear and, then again, others which are uniquely obscure. Tracking down the reasons for these, especially for the latter phenomena, always appealed to me, and still does, and the construction of the wall is fundamentally concerned with these issues.

Nezahualcóyoltl, Mexico: photo by Tonatiuh Cabello, 30 May 2012

Now,

among our most obscure institutions one can certainly include the

empire itself. Of course, in Peking, right in the court, there is some

clarity about it, although even this is more apparent than real. And

the teachers of constitutional law and history in the high schools give

out that they are precisely informed about these things and that they

are able to pass this knowledge on to their students. The deeper one

descends into the lower schools, the more the doubts about the

students’ own knowledge understandably disappear, and a superficial

education surges up as high as a mountain around a few precepts drilled

into them for centuries, sayings which, in fact, have lost nothing of

their eternal truth, but which remain also eternally unrecognized in

this mist and fog.

Afternoon light on the gorge of the Yangzi River, Yunnan Province: photo by Peter Morgan, 2005

But,

in my view, it’s precisely the empire we should be asking the people

about, because in them the empire has its final support. It’s true that

in this matter I can speak once again only about my own homeland.

Other than the agricultural deities and the service to them, which so

beautifully and variously fills up the entire year, our thinking

concerns itself only with the emperor. But not with the present emperor. We

would have concerned ourselves with the present one if we had

recognized who he was or had known anything definite about him. We were

naturally always trying—and it’s the single curiosity which consumed

us—to find out something or other about him, but, no matter how strange

this sounds, it was hardly possible to learn anything, either from

pilgrims, even though they wandered through much of our land, or from

the close or remote villages, or from boatmen, although they have

travelled not merely on our little waterways but also on the sacred

rivers. Of course, we heard a great deal, but could gather nothing from

the many details.

The Construction of the Tower of Babel (The "little" Tower of Babel), detail: Pieter Bruegel the Elder, c. 1563 (Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen, Rotterdam)

Our

land is so huge, that no fairy tale can adequately deal with its size.

Heaven hardly covers it all. And Peking is only a point, the imperial

palace only a tiny dot. It’s true that, by contrast, throughout all the

different levels of the world the emperor, as emperor, is great. But

the living emperor, a human being like us, lies on a peaceful bed, just

as we do. It is, no doubt, of ample proportions, but it could be

merely narrow and short. Like us, he sometimes stretches out his limbs

and, if he is very tired, yawns with his delicately delineated mouth.

But how are we to know about that thousands of miles to the south,

where we almost border on the Tibetan highlands? Besides, any report

which might come, even if it reached us, would get there much too late

and would be long out of date. Around the emperor the glittering and

yet murky court throngs—malice and enmity clothed as servants and

friends, the counterbalance to the imperial power, with their poisoned

arrows always trying to shoot the emperor down from his side of the

balance scales. The empire is immortal, but the individual emperor

falls and collapses. Even entire dynasties finally sink down and

breathe their one last death rattle. The people will never know

anything about these struggles and suffering. Like those who have come

too late, like strangers to the city, they stand at the end of the

thickly populated side alleyways, quietly living off the provisions

they have brought with them, while far off in the market place right in

the middle foreground the execution of their master is taking place.

The Construction of the Tower of Babel (The "little" Tower of Babel), detail: Pieter Bruegel the Elder, c. 1563 (Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen, Rotterdam)

There

is a legend which expresses this relationship well. The Emperor—so

they say—has sent a message, directly from his death bed, to you alone,

his pathetic subject, a tiny

shadow which has taken refuge at the furthest distance from the imperial

sun. He ordered the herald to kneel down beside his death bed and

whispered the message to him. He thought it was so important that he

had the herald repeat it back to him. He confirmed the accuracy of the

verbal message by nodding his head. And in front of the entire crowd of

those who have come to witness his death—all the obstructing walls

have been broken down and all the great ones of his empire are standing

in a circle on the broad and high soaring flights of stairs—in front

of all of them he dispatched his herald. The messenger started off at

once, a powerful, tireless man. Sticking one arm out and then another,

he makes his way through the crowd. If he runs into resistance, he

points to his breast where there is a sign of the sun. So he moves

forward easily, unlike anyone else. But the crowd is so huge; its

dwelling places are infinite. If there were an open field, how he would

fly along, and soon you would hear the marvelous pounding of his fist

on your door. But instead of that, how futile are all his efforts. He

is still forcing his way through the private rooms of the innermost

palace. He will never win his way through. And if he did manage that,

nothing would have been achieved. He would have to fight his way down

the steps, and, if he managed to do that, nothing would have been

achieved. He would have to stride through the courtyards, and after the

courtyards the second palace encircling the first, and, then again,

stairs and courtyards, and then, once again, a palace, and so on for

thousands of years. And if he finally did burst through the outermost

door—but that can never, never happen—the royal capital city, the

centre of the world, is still there in front of him, piled high and full

of sediment. No one pushes his way through here, certainly not with a

message from a dead man. But you sit at your window and dream to

yourself of that message when evening comes.

The Construction of the Tower of Babel (The "little" Tower of Babel): Pieter Bruegel the Elder, c. 1563 (Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen, Rotterdam)

Indeed,

procrastination is the true meaning of that noteworthy and often

striking fullness of detail which according to Max Brod lay at the heart

of Kafka's search for perfection and the true way. Brod observes: "Of

all the aspects of life to be taken seriously, we may say what a girl

in Das Schloss

says of the enigmatic letters from the authorities -- namely that 'the

reflections to which they give rise are interminable.'" But what Kafka

enjoys about these interminable reflections is the very fear that they

might come to an end.

Walter Benjamin: Franz Kafka: Beim Bau der Chinesischen Mauer (The Great Wall of China), radio talk broadcast July 1931, translated by Rodney Livingstone in Selected Writings, Volume 2: 1927-1934, 1999

Zeno of Elea's Racecourse Paradox: Suppose a runner needs to travel

from a start S to a finish F. To do this he must first travel to the

midpoint, M, and thence to F: but if N is the midpoint of SM, he must

first travel to N, and so on ad infinitum (Zeno: ‘what has been

said once can always be repeated’). But it is impossible to accomplish

an infinite number of tasks in a finite time. Therefore the runner

cannot complete (or start) his journey.

Oxford Dictionary of Philosophy

Oxford Dictionary of Philosophy

A boy peeks out of the window of his house in Nuevo Laredo, Tamaulipas state, Mexico, across the border from Laredo in the U.S, on Friday: photo by Rodrigo Abd/AP, 24 March 2017

"I would just move the company"

Ironhorse

loads up for the NTC. The 297th Inland Cargo Transfer Company, 180th

Transportation Battalion, 13th Sustainment Command helps Company A of

the 115th "Muleskinner" Brigade Combat Team, 1st Cavalry Division load

and transport shipping containers to Fort Hood's railhead in preparation

for the National Training Center.: U. S. Army photo by Pfc. Paige Pendleton, 1st Battalion Combat Team PAQ, 1st Cavalry Division, 14 January 2014

The beauty pageant to build Trump's border wall is beginning: Proposal deadline is first step in a process that combines three of

the president’s most successful ventures: pageants, reality TV

competitions and xenophobia: Julia Carrie Wong in San Francisco for The Guardian, 29 March 2017

Wednesday marks the deadline for the hundreds of companies interested in building Donald Trump’s signature campaign promise – a “great, great wall” on the US-Mexico border – to submit concept papers detailing their proposals.

It is the first step in a process that promises to combine

three of Trump’s most successful ventures: beauty pageants, reality TV

competitions and xenophobia.

After an initial elimination round, the remaining

contestants will submit more detailed technical proposals. Another round

of cuts will ensue, and then a group of finalists will convene in San

Diego, California, to construct both a 30ft-long prototype of their

design and a 10ft by 10ft “mock-up” that will be used by the government

to “test and evaluate the anti-destruct characteristics” of the design.

Think of it as a swimsuit competition followed by a

high-stakes Apprentice challenge. Those who can withstand the battering

ram for at least 90 minutes while also being “aesthetically pleasing”

(on the US-facing side) have a shot at winning a lucrative piece of one

of the US government’s largest infrastructure projects in decades.

Ironhorse

loads up for the NTC. The 297th Inland Cargo Transfer Company, 180th

Transportation Battalion, 13th Sustainment Command helps Company A of

the 115th "Muleskinner" Brigade Combat Team, 1st Cavalry Division load

and transport shipping containers to Fort Hood's railhead in preparation

for the National Training Center.: U. S. Army photo by Pfc. Paige Pendleton, 1st Battalion Combat Team PAQ, 1st Cavalry Division, 14 January 2014

The government’s initial pre-solicitation notice for the border wall asked for 30ft-tall “concrete wall structures”, but

when the request for proposals was published on 17 March, the scope was

expanded to allow for “other” proposals. So while some companies will

move ahead with reinforced concrete, others can put forward ideas for

alternative materials.

All proposals must meet some baseline standards, including

being “physically imposing in height” with “anti-climb” features and

“aesthetically pleasing” color on the north side. Non-concrete walls are

also required to have a “see-through component” to increase

“situational awareness”.

Matt Kaye of Integrated Security Corporation plans to submit a proposal with a group of other companies

that calls for two chain-link fences with a “no man’s land in between”

and his company’s intrusion detection systems in place. Kaye described

the concept as a “typical correctional type fence” (his company has

contracted for federal, state and local prisons) and said it would be

“far less expensive and far less intrusive” than a concrete wall.

Liz Derr, the founder and CEO of artificial intelligence

company Simularity, is proposing an “invisible or virtual wall” that

uses AI software to analyze satellite and surveillance imagery to

identify unusual activities.

Derr, who said that her company is “pro-immigration” and

“pro-diversity”, argued that a hi-tech solution to border security could

provide a 90% saving to the government, though she assumed her concept

would not be chosen since it does not include any physical barrier.

Kalmar Rough Terrain Center has an alternative idea for that physical barrier: shipping containers.: photo by Steve Speakes / Kalmar via The Guardian, 29 March 2017

Steve

Speakes, the president and CEO of Kalmar Rough Terrain

Center, has an alternative idea for that physical barrier: shipping

containers. Kalmar produces machines that can move shipping containers

in difficult terrain, so Speakes is hoping that any winning contractor

will be interested in his equipment. But he also strongly approved of

the idea of using the containers themselves as the building blocks for

the wall – as was proposed by a Florida architecture firm earlier this

year. The “sustainable” design drew immediate backlash (one

architecture site called it “the Bushwick of xenophobic nationalism”),

but Speakes defended the concept.

“That

is a very reasonable way to build a wall,” he said, noting that there

is a surplus of containers available now due to a slowdown in global

commerce.

Notably

absent from the list of interested contractors are any of the large,

multinational corporations that would probably have the capacity to

carry out the 1,000, $21bn project.

[Untitled]: photo by Tonatiuh Cabello, 3 August 2015

Such

companies may be put off by toxic politics surrounding

the project (62% of Americans oppose building the wall, according to a

February poll by the Pew Research Center), and the difficult path to

actually funding

it. The lack of name-brand bidders and challenge of getting the wall

through Congress have led some to speculate that the San Diego prototype

pageant will be as far as the project ever gets.

“The wall was a campaign promise,” said Phil Ting, a state

assembly member from California. “The administration is probably trying

to do the absolute minimum to gain the maximum press. I can see why

they’d want to cause the biggest possible splash, and then go quietly

away.”

After an initial elimination round, the remaining contestants will submit more detailed technical proposals for the wall: photo by Guillermo Arias/AFP via The Guardian, 29 March 2017

After an initial elimination round, the remaining contestants will submit more detailed technical proposals for the wall: photo by Guillermo Arias/AFP via The Guardian, 29 March 2017

Ting, a Democrat from San Francisco, is one of several state

and local legislators who are hoping to scare off potential bidders for

the project with threats of blacklists and divestment.

“We don’t want a single California cent going toward building this wall,” Ting said of the Resist Wall Act, which would require the state’s two giant pension funds to divest from any companies that take part in building the wall. Ting compared the measure to the divestment campaigns against Apartheid South Africa.

Lawmakers

in other states, including New York, Illinois and Arizona,

have proposed barring any involved companies from receiving state

contracts. The city of Berkeley, California, has already passed a

boycott measure, and other municipalities are considering following

suit.

Companies on the other side of the border are facing pressure as well. The Mexican government warned

of reputational damage to firms that might be interest in providing

materials for the wall, such as Cemex, a Mexican cement producer. The

Catholic archdiocese of Mexico wrote

in an op-ed that any participating company would be “immoral” and that

its shareholders and owners “should be considered traitors to the

homeland”.

Nezahualcóyoltl, Mexico: photo by Tonatiuh Cabello, 30 May 2012

Nezahualcóyoltl, Mexico: photo by Tonatiuh Cabello, 30 May 2012

Still, some businessmen are more interested in the morality

of employing their workers than the morality of keeping out migrants.

Speake, who said he’s had to lay off employees over the past two years,

said the opportunity to work on the wall was “heaven sent”.

Ron Schoenheit, the president of Cascade Coil, an

Oregon-based company that makes woven wire products, said that he would

not be deterred by backlash.

“If we did get some work on this project and people found

out about it, as liberal as the city of Portland is, they would probably

come burn our factory down,” he said. But that wouldn’t stop him, he

said.

“If it was a big contract, I would just move the company.”

Ironhorse loads up for the NTC. The 297th Inland Cargo Transfer Company, 180th Transportation Battalion, 13th Sustainment Command helps Company A of the 115th "Muleskinner" Brigade Combat Team, 1st Cavalry Division load and transport shipping containers to Fort Hood's railhead in preparation for the National Training Center.: U. S. Army photo by Pfc. Paige Pendleton, 1st Battalion Combat Team PAQ, 1st Cavalry Division, 14 January 2014

from Kafka's Diaries: The real fun side of writing

The Tower of Babel (detail): Pieter Bruegel the Elder, 1563, oil on oak panel (Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna)

I am powerless.

I am powerless.

The Tower of Babel (detail): Pieter Bruegel the Elder, 1563, oil on oak panel (Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna)

Complete standstill. Unending torments.

The Tower of Babel (detail): Pieter Bruegel the Elder, 1563, oil on oak panel (Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna)

How time flies; another ten days, and I have achieved nothing.

The Tower of Babel (detail): Pieter Bruegel the Elder, 1563, oil on oak panel (Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna)

A page now and then is successful, but I can't keep it up.

The Tower of Babel (detail): Pieter Bruegel the Elder, 1563, oil on oak panel (Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna)

A page now and then. The next day I am powerless.

The Tower of Babel (detail): Pieter Bruegel the Elder, 1563, oil on oak panel (Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna)

Complete standstill.

The Tower of Babel (detail): Pieter Bruegel the Elder, 1563, oil on oak panel (Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna)

I can't keep it up.

I can't keep it up.

The Tower of Babel (detail): Pieter Bruegel the Elder, 1563, oil on oak panel (Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna)

You have to dive down, as it were,

and sink more rapidly

than that which sinks in advance of you.

The Tower of Babel (detail): Pieter Bruegel the Elder, 1563, oil on oak panel (Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna)

You have to dive down, as it were.

You have to dive down, as it were.

The Tower of Babel (detail): Pieter Bruegel the Elder, 1563, oil on oak panel (Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna)

Kafka's diaries show the real fun side of writing.: image via Matt Haig @matthaig1, 19 March 2017

Por aquí no pasó Dios: photo by Tonatiuh Cabello, 24 September 2015

A boy peeks out of the window of his house in Nuevo Laredo, Tamaulipas state, Mexico, across the border from Laredo in the U.S, on Friday: photo by Rodrigo Abd/AP, 24 March 2017

[Untitled]: photo by Tonatiuh Cabello, 4 March 2017