.

"Film is 24 lies per second at the service of truth, or at the service of the attempt to find the truth." -- Michael Haneke

It is 1913, 1914... a quiet rural Protestant village in northern Germany, on the eve of the First World War. Mysterious and ominous incidents are inexplicably occurring, unsettling the inhabitants of the small isolated community.

The town doctor, coming home from his appointed rounds, is thrown from his horse by a trip-wire concealed in the road. The local baronial landowner's son disappears, then is found bound and whipped. The baron's cabbage crop is destroyed. A window is left open, letting cold night air into the room where the steward's newborn child sleeps. The wife of a tenant farmer falls through rotted floorboards of a sawmill and perishes. The barn of the manor house is set ablaze in the night and burns to the ground. A farmer hangs himself. The local pastor's beloved pet canary is killed.

At the center of the bizarre events are the children who attend the local church and school, their families, and the village schoolteacher. Suspicion falls upon the children -- our suspicion, that is; as well as that of the schoolteacher, who, a typical Haneke character, equivocates in this knowledge. The events take on eerie aspects of ritual punishment. But the mystery remains unsolved... who is responsible for the transgressions? What motives or forces underlie these strange happenings?

The restrictions and disciplines imposed by the parents upon the children of the village are humiliating and cruel. The pastor forces two of his children to wear a white ribbon, visible symbol of their lost innocence. He whips his oldest son behind closed doors, and orders his hands tied at night to keep him from masturbating. In an especially unsettling cut we are given briefly to think we are seeing the pastor sodomizing his son. Instead the next shot reveals that what we are seeing is the doctor having sex with the midwife. (If this hint of incest proves a false one, we are shortly given sure evidence of the real thing occurring between different parties on the doctor's examining couch.)

In The White Ribbon, as often with Haneke, guilt is the subject. And it is not merely left to the spectator to determine where the guilt may lie; there is also a persistent, nagging sense that the direction of accusation has been reversed, and the audience itself has become anxiously complicit in some central unsolved crime. It was Haneke's leaving open this possibility of a shared responsibility for a crime that caused audiences to depart so uneasily from his masterpiece Caché.

The town doctor, coming home from his appointed rounds, is thrown from his horse by a trip-wire concealed in the road. The local baronial landowner's son disappears, then is found bound and whipped. The baron's cabbage crop is destroyed. A window is left open, letting cold night air into the room where the steward's newborn child sleeps. The wife of a tenant farmer falls through rotted floorboards of a sawmill and perishes. The barn of the manor house is set ablaze in the night and burns to the ground. A farmer hangs himself. The local pastor's beloved pet canary is killed.

At the center of the bizarre events are the children who attend the local church and school, their families, and the village schoolteacher. Suspicion falls upon the children -- our suspicion, that is; as well as that of the schoolteacher, who, a typical Haneke character, equivocates in this knowledge. The events take on eerie aspects of ritual punishment. But the mystery remains unsolved... who is responsible for the transgressions? What motives or forces underlie these strange happenings?

The restrictions and disciplines imposed by the parents upon the children of the village are humiliating and cruel. The pastor forces two of his children to wear a white ribbon, visible symbol of their lost innocence. He whips his oldest son behind closed doors, and orders his hands tied at night to keep him from masturbating. In an especially unsettling cut we are given briefly to think we are seeing the pastor sodomizing his son. Instead the next shot reveals that what we are seeing is the doctor having sex with the midwife. (If this hint of incest proves a false one, we are shortly given sure evidence of the real thing occurring between different parties on the doctor's examining couch.)

In The White Ribbon, as often with Haneke, guilt is the subject. And it is not merely left to the spectator to determine where the guilt may lie; there is also a persistent, nagging sense that the direction of accusation has been reversed, and the audience itself has become anxiously complicit in some central unsolved crime. It was Haneke's leaving open this possibility of a shared responsibility for a crime that caused audiences to depart so uneasily from his masterpiece Caché.

Michael Haneke is a filmmaker of great aesthetic austerity. There is a cold surgical rigor about his films. They routinely invert the normal kind of movie/audience relations, upsetting the customary expectation of the viewer that s/he may remain a passive recipient of the moviewatching experience. Haneke is an exacting and demanding master who requires his audiences to become intellectual and moral participants in the aesthetic event.

With most movies, one stares at the images, thus remaining in control of the viewing experience. With Haneke's movies it is as though the film were staring at its viewers, putting a series of difficult questions, insisting that what is being seen and heard be taken as the beginning of a thought process that will continue well after the viewing experience itself has ended.

The repressions, hypocrisies, deceptions and self-deceptions of the characters in Haneke's films have a way of uncomfortably mirroring the interior convolutions of the psyche of the viewer; one imagines that unexpected reflection to be a large part of the point of the films, in fact. Haneke has said he expects audiences of his films always to know when a character is lying. He imposes a similarly stringent self-knowledge upon the viewer, who is forced to scrutinize her/his responses in a way few other directors dare ask of audiences. To have fully experienced a Haneke film is not only to have been implicated in something but to have survived a self-inquisition.

The White Ribbon is shot in starkly magnificent black and white monochrome, tonally resonant with its often grimly Grimm-like parabolic subject matter. (Its German sub-title is Eine Deutsche Kindergeschichte, or "A German Children's Story"; the child actors in the film are mostly nonprofessionals, chosen for their resemblance to a desired historical "look"; Haneke has said 7000 schoolchildren were interviewed for the fifteen children's roles in the film.) The films it most closely evokes in tone and visual style are Dreyer's Ordet and certain works of Bresson like Pickpocket and Diary of a Country Priest. But the exalted spiritual dimensions of a Dreyer or a Bresson have no corollary in Haneke's frigid, fallen universe. (Asked about whether he believes in God, the director is to have said he would no more answer such a question than speak about his private sexual practices.)

The film is the product of an idea Haneke has shaped over two decades. It is plain that the children we are seeing are to be understood as the generation who would become the audience of Hitler. In interviews the Austrian director has made no secret of the fact that he constructed his film as a study of the origins of Fascism. "I chose this period in this country because I think it offers the [sources of] the most prominent horror in any country at any time. I think German people should see it as a film about Germany. But in other countries people should see it as a film about their own countries."

It's a film about the growth of "absolute ideologies," Haneke says. "A children's choir in Protestant Germany elevates their parents' preachings to the level of an absolute ideology and then judges their parents on the basis of that ideology."

As always with Haneke, the problematics of the work are meticulously applied at the level of scene construction. The audience, Haneke assumes, wants to know who's guilty. "I always try to construct my stories in such a way that a number of different explanations [of events] are possible. I give the spectator all possible freedom to construct the story."

Haneke's method is identifiable from film to film. Show only what is essential. Come into a scene late, exit early. Leave out more than you put in. A Haneke ellipsis can be a precipice that slips off into an abyss of uncertainty. "I excite the imagination of the spectator through everything I don't show, all the questions I don't answer."

The White Ribbon's Narrator (the village schoolteacher, looking back in later years) reveals at the outset of the film that he too may be in the dark about the events which he is to unfold for us:

"I don't know if the story I'm about to tell you is true in all respects. Some of it I know only from hearsay..."

It must be honestly admitted that the extended durations and hanging questions of the work, the resolute refusal of solution and closure, the studied wide-angle framings and the chilly black and whites, render The White Ribbon somewhat less than... a New Years Eve date movie?

Haneke's film is nearly three hours long and builds slowly. In its last hour an intensity accumulates and the always coolly distanced camera eye gradually achieves a cruelty and coldness similar to that warily trained upon one another by the villagers themselves: capturing them without mercy, as in a petri dish. This is a town where "apathy, envy, brutality and malice" (as the baron's unhappy wife, taking her departure, puts it) are all there is.

In the final scenes of the film many takes are extended. In Haneke's hands the inherent melancholy of the time-expanding long take is complicated by shivers of irony. As the damned children of the village of the damned lounge by a stream in carefully feigned nonchalance between violent depredations, we are perhaps seeing tomorrow's Hitler youth in their first expectant days. The film ends with the assassination of the Archduke Ferdinand at Sarajevo, sutured into history by Michael Haneke with brilliance and care and reverberating unanswered questioning.

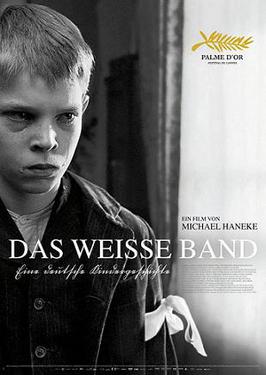

The White Ribbon (directed by Michael Haneke), 2009: theatrical poster (Sony Pictures Classics)

Hitler Youth, c.1933, training with gas masks: photo from German Federal Archive

The Alliance of Work and People, April 1934: photo from German Federal Archive

Yikes, Tom,

ReplyDeletefirst The Messenger, now Haneke! I better bring you by Darby O'Gill and the Little People or The Lady and the Tramp for the New Year or who knows where you are heading next.

But, it is a brilliant overview actually of all Haneke...who just keeps on digging deeper and deeper on the same truth serum and broad pan sniper camera.

The original Funny Games had just the black magic, then he forced the remake and I'm now convinced the poor guy is a bit of a sick mutt. With courage. And, after all, not quite Henri-Georges Clouzot.

Bob,

ReplyDeleteMany thanks. My attempt to spring the poor guy from the kennel jumped over the comment box fence and landed here.

"Fascism can come from any point

ReplyDeleteon the political compass" PJ O'Rourke.

These days I would be more worried

about the soft fascism of the politically correct left or clerical fascism of Islmaic extremists than the right(atleast

today). When I read Celine's trilogy of exile, it helped me

understand the human appeal of

fascism in a time of social

disintegration. The real Nazis

had more than a political ideology

and system, they had a religion.

I'm looking forward to seeing the

White Ribbon after TC's description. By the way, I have,

over the years developed, a simple

criteria for deeper friendships:it's this;If the Nazis

ever showed up again, who would

stand and fight. Some of the time

it's not who you would think it

would be...just look around.

Elmo,

ReplyDeleteFrom the statements he has made about this film, I think Michael Haneke would agree with the thrust of your comment.

E.g.:

"The film is an example intended to show what conditions have to be in place for children and for people to be turned into victims of an ideology. Depending on the context, that ideology can be right wing, it can be left wing, it can be political or religious. But I took the example of German fascism because it's the most prominent, it's the best-known example of such an ideology.

"I see it as a timeless subject. It's always the same that when people anywhere are in a situation of depression, of oppression, of humiliation, of suffering, when they see no way out, they are eager victims and will listen hungrily to anyone who says, 'I know how you can save yourselves. I know how you can get revenge. I know how you can get out of that situation.'"