.

A Scene from The Beggar's Opera, Act V: William Hogarth, 1728-1729, oil on canvas, 51 x 61 cm (National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.)

Act Three. Scene 13. The Condemn'd Hold

MACHEATH, in a melancholy Posture.

Air LXVII.--Green Sleeves.

Since Laws were made for ev'ry Degree,JAILOR. Some Friends of yours, Captain, desire to be admitted----I leave you together.

To curb Vice in others, as well as me,

I wonder we han't better Company,

Upon Tyburn Tree!

But Gold from Law can take out the Sting;

And if rich Men like us were to swing,

'Twould thin the Land, such Numbers to string

Upon Tyburn Tree!

Scene 14.

MACHEATH, BEN BUDGE, MATT OF THE MINT.

MACHEATH. For my having broke Prison,

you see, Gentlemen, I am order'd immediate Execution.----The Sheriff's

Officers, I believe, are now at the Door.----That Jemmy Twitcher should

peach me, I own surpris'd me!----'Tis a plain Proof that the World is

all alike, and that even our Gang can no more trust one another than

other People. Therefore, I beg you, Gentlemen, look well to yourselves,

for in all probability you may live some Months longer.

MATT. We are heartily sorry, Captain,

for your Misfortune.----But 'tis what we must all come to.

MACHEATH. Peachum and Lockit, you

know, are infamous Scoundrels. Their Lives are as much in your Power,

as yours are in theirs.----

Remember your dying Friend!----'Tis my last Request.----Bring those Villains to the Gallows before you, and I am satisfied.

MATT. We'll do it.

JAILOR. Miss Polly and Miss Lucy

intreat a Word with you.

MACHEATH. Gentlemen, adieu.

Scene 15.

LUCY, MACHEATH, POLLY.

MACHEATH. My dear Lucy----My dear

Polly. Whatsoever hath pass'd between us is now at an end----if you are

fond of marrying again, the best Advice I can give you is to Ship

yourselves to the West-Indies, where you'll have a fair Chance of

getting a Husband a-piece, or by good Luck, two or three, as you like

best.

POLLY. How can I support this Sight!

LUCY. There is nothing moves one so

much as a great Man in Distress.

Air LXVII.----All you that must take a

Leap, & c.

LUCY.

LUCY.

Would I might be hang'd!POLLY.

And I would so too!LUCY.

To be hang'd with you.POLLY.

My dear, with you.MACHEATH.

O leave me to Thought! I fear! I doubt!POLLY.

I tremble! I droop!----See, my Courage is out! [Turns up the empty Bottle.]

No Token of Love?MACHEATH.

See, my Courage is out. [Turns up the empty Pot.]LUCY.

No Token of Love?POLLY.

Adieu.LUCY.

Farewell.MACHEATH.

But hark! I hear the Toll of the Bell.CHORUS.

Tol de rol lol, &c.JAILOR. Four Women more, Captain, with a Child apiece! See, here they come. [Enter Women and Children.]

MACHEATH. What----four Wives

more!----This is too much----Here----tell the Sheriff's Officers I am

ready. [Exit Macheath guarded.]

Scene 16.

To them, Enter PLAYER and BEGGAR.

PLAYER. But, honest Friend, I hope you

don't intend that Macheath shall be really executed.

BEGGAR. Most certainly, Sir.----To make

the Piece perfect, I was for doing strict poetical Justice----Macheath

is to be hang'd; and for the other Personages of the Drama, the

Audience must have suppos'd they were all hang'd or transported.

PLAYER. Why then Friend, this is a

downright deep Tragedy. The Catastrophe is manifestly wrong, for an

Opera must end happily.

BEGGAR. Your Objection, Sir, is very

just, and is easily remov'd. For you must allow, that in this kind of

Drama, 'tis no matter how absurdly things are brought

about----So----you Rabble there----run and cry, A Reprieve! ----let the Prisoner

be brought back to his Wives in Triumph.

PLAYER. All this we must do, to comply

with the Taste of the Town.

BEGGAR. Through the whole Piece you may

observe such a Similitude of Manners in high and low Life, that it is

difficult to determine whether (in the fashionable Vices) the fine

Gentlemen imitate the Gentlemen of the Road, or the Gentlemen of the

Road, the fine Gentlemen.----Had the Play remain'd, as I first intended, it would have carried a most excellent Moral. 'Twould have shown that the lower sort of People have their Vices in a degree as well as the Rich: And that they are punish'd for them.

John Gay (1685-1732): from The Beggar's Opera (1728)

Lavinia Fenton (1710-1760), later Duchess of Bolton, as Polly Peachum in John Gay's The Beggar's Opera: Charles Jervas (1675-1739), 18th c., oil on canvas, 127 x 102.8 cm (Christie's)

Apron worn by Lavinia Fenton in originating the role of Polly Peachum in John Gay's The Beggar's Opera, 1728: photo by Lauren, 12 January 2005

Finale scene from Robert Wilson production of The Threepenny Opera (Die Dreigoschenoper), Berlin 2008: photo by Colya Kärcher (via Susan Berenofsky: The Berlin Blog)

"Swift's first conception of it -- the pastoral method applied to Newgate"

___

"There

is a natural connection between heroic and pastoral before they are

parodied, and this gives extra force to the comic mixture. Both when in

their full form assume or preach what the parody need not laugh at, a

proper or beautiful relation between rich and poor. Hence they belong to

the same play -- they are the two stock halves of the double plot.

"Clearly

it is important for a nation with a strong class system to have an

art-form that not merely evades but breaks through it, that makes the

classes feel part of a larger unity or simply at home with each other.

This may be done in odd ways, as well by mockery as admiration. The

half-conscious purpose behind the magical ideas of heroic and pastoral

was being finely secured by the Beggar's Opera when the mob roared its

applause both against and with the applause of Walpole.

"One

of the traditional ideas at the back of the hero was that he was half

outside morality, because he must be half outside his tribe in order to

mediate between it and God, or it and Nature.... This in a queer way was

still alive in the theatre; the perversion of human feeling might not

be justified in the Restoration tragic hero, because he was so ideal,

and the Restoration comic hero was a rogue because he was an aristocrat.

The process of fixing these forms into conventions, the Tragedy of Admiration and the comedy of the predatory wit, undertaken because the former had come to seem unreal,

for some reason brought out their primitive ideas more sharply. Now on

the one hand, this half-magical view seemed to the Augustans wicked as

well as ridiculous; all men were men; they had just put down the

witch-burnings; to a rational pacifism Marlborough and Alexander were

bullies glorified by toadies. On the other hand, they were Tory poets,

and the heroic tradition, always royalist (the King's divine right made the best magical symbol),

had died on their hands. The only way to use the heroic convention was

to turn it into the mock-hero, the rogue, the man half-justified by

pastoral, and the only romance to be extracted from the Whig government

was to satirise it as the rogue. The two contradictory feelings were

satisfied by the same attitude.

"The

rogue so conceived is not merely an object of satire; he is like the

hero because he is strong enough to be independent of society (in some

sense), and can therefore be the critic of it..."

___

"I

should say then that the essential process behind the Opera was a

resolution of heroic and pastoral into a cult of independence. But the

word is capable of great shift of meaning, chiefly because nobody can be

independent altogether; Gay meant Peachum to be the villain, and there

is a case for thinking him more independent than Macheath; the animus

against him seems more than that due to a traitor; Gay dislikes him as a

successful member of the shopkeeping middle class, whereas Macheath is

either from a high class or a low one..."

William Empson: from The Beggar's Opera: Mock Pastoral as the Cult of Independence in Some Versions of Pastoral, 1935

Lavinia Fenton (1710-1760), later Duchess of Bolton, as Polly Peachum in John Gay's The Beggar's Opera: Charles Jervas (1675-1739), 18th c., oil on canvas, 127 x 102.8 cm (Christie's)

Apron worn by Lavinia Fenton in originating the role of Polly Peachum in John Gay's The Beggar's Opera, 1728: photo by Lauren, 12 January 2005

An execution outside Newgate Prison: Thomas Rowlandson, between 1805 and 1810, ink and watercolour over pencil

The Beggar's Opera: print by Thomas Rowlandson, n.d. (via Grub Street EC2)

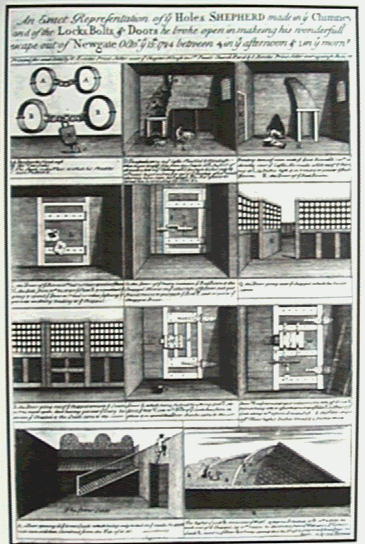

The

infamous outlaw Jack Sheppard, thought to be the "original" of John

Gay's Captain MacHeath, pointing to the door of his cell, plotting

another daring escape: engraving by George White, based on a

painting by James Thornhill made while the subject awaited

execution in Newgate Prison, 1728; plate from Christopher Hibbert, The Road to Tyburn, 1957; image by Geogre, 4 February 2007

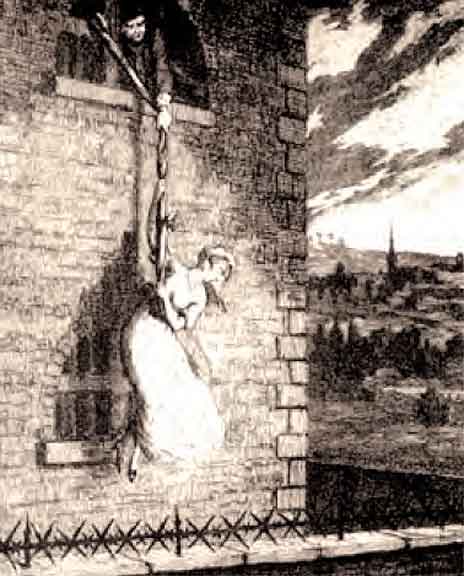

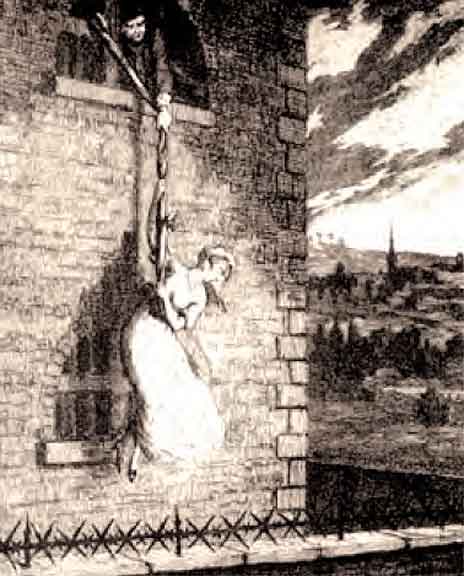

Jack Sheppard uses a rope of knotted bedclothes to lower his mistress Bess Lyon during their escape from New Prison in Clerkenwell, 25 May 1724: artist unknown

Jack Sheppard, notorious outlaw thought to have been the model for John Gay's MacHeath in The Beggar's Opera, in Newgate Prison before his fourth escape; the label "A" in the brickwork at rear marks the hole Sheppard made in the chimney during his escape: anonymous frontispiece drawing from the Narrative of Jack Sheppard's Life, published by John Applebee in 1724; image by RetiredUser2, 29 January 2007

Jack Sheppard uses a rope of knotted bedclothes to lower his mistress Bess Lyon during their escape from New Prison in Clerkenwell, 25 May 1724: artist unknown

Jack Sheppard, notorious outlaw thought to have been the model for John Gay's MacHeath in The Beggar's Opera, in Newgate Prison before his fourth escape; the label "A" in the brickwork at rear marks the hole Sheppard made in the chimney during his escape: anonymous frontispiece drawing from the Narrative of Jack Sheppard's Life, published by John Applebee in 1724; image by RetiredUser2, 29 January 2007

Wych Street, off Drury Lane, near Covent Garden, London; on this street Jack Sheppard, thought to be the original of John Gay's highwayman MacHeath, was indentured as a carpenter's apprentice in 1717: anonymous engraving, c. 1870 (Theatreleands Metropolitan Archive)

Jack Sheppard Gets Drunk: engraving by George Cruikshank (1792-1878), c. 1840 to illustrate the serialised novel Jack Sheppard by William Harrison Ainsworth, published in Bentley's Miscellany from January 1839

Jack Sheppard in the Stone Room in Newgate: anonymous engraving from Lives Of The Most Remarkable Criminals Who have been Condemned and Executed for Murder, the Highway, Housebreaking, Street Robberies, anon., n.d.

Jack Sheppard in Newgate: anonymous engraving from Jack Sheppard, Jail-Breaker in Norton, Richter: Early Eighteenth-Century Newspaper Reports: A Sourcebook

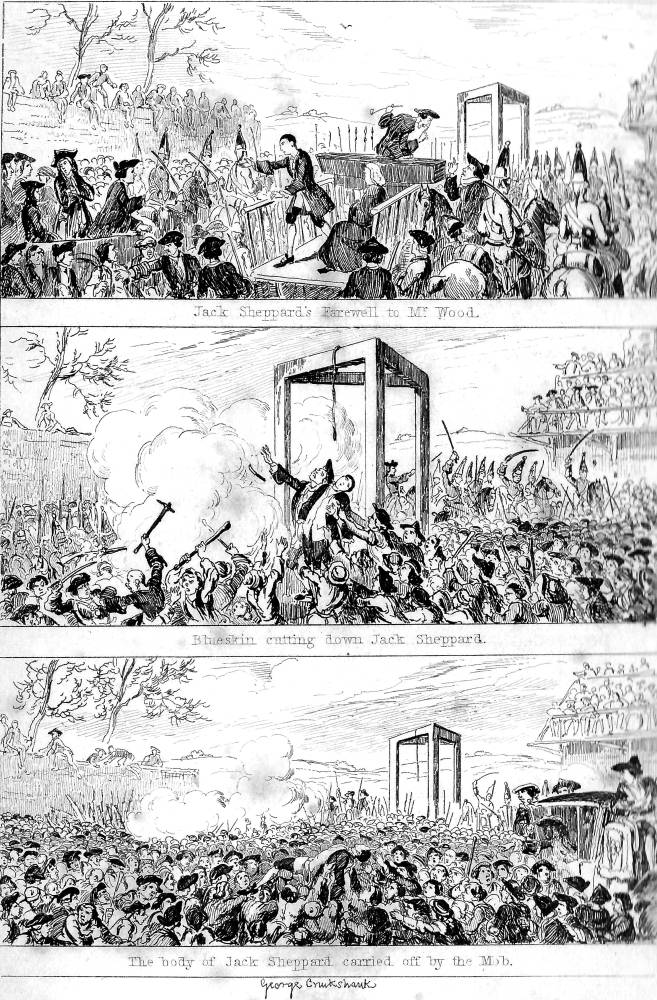

The Last Scene: engravings by George Cruikshank to illustrate the serialised novel Jack Sheppard by William Harrison Ainsworth, published in Bentley's Miscellany from January 1839; the captions read: "Jack Sheppard's Farewell to Mr Wood", "Blueskin cutting down Jack Sheppard", and "The body of Jack Sheppard carried off by the mob".

Scene from The Beggar's Opera:

print by John Doyle, b&w, 31 x 45 cm, published by Thos. McLean, 26

Haymarket, London, 15 December (Tabley House Collection Trust, University of Manchester / British Cartoon Archive, University

of Kent)

Scene from The Beggar's Opera: print by John Doyle, b&w, 31 x 45 cm, published by Thos. McLean, 26 Haymarket, London, 14 April 1841 (Tabley House Collection Trust. University of Manchester / British Cartoon Archive, University

of Kent)

Scene from The Beggar's Opera: print by John Doyle, b&w, 31 x 45 cm, published by Thos. McLean, 26 Haymarket, London, 8 April 1841 (Tabley House Collection Trust, University of Manchester / British Cartoon Archive, University of Kent)

The Beggar's Opera: print after William Hogarth (1697-1764), b & w, 58 x 45 cm, published by G. & J. Robinson, Paternoster Lane, London, 8 April 1841 (University of Manchester / British Cartoon Archive, University of Kent)

Old Bailey: drawing by Thomas Rowlandson and Augustus Pugin, aquatinting by Joseph Stadler, from Ackermann's Microcosm of London, 1808

Newgate Chapel: drawing by Thomas Rowlandson and Augutus Pugin, auatinting by J. Bluck, from Ackermann's Microcosm of London, 1808

Newgate took its name from one of the gates of the City of London. It was the jail for the most serious criminals. According to William Pyne, author of the Microcosm of London (1808), on the Sunday before the condemned were scheduled to die, the 'Ordinary' (the clergyman) of Newgate preached a special sermon in the jail's chapel. A black coffin would be placed on a table in the centre of the chapel (known as the dock). Those condemned to die sat immediately around the coffin.

The political activist, Francis Place, described his experience of visiting Newgate Prison in the mid-1790s:

"In

1794 I was several times in Newgate on visits to

persons confined for libel & c. -- one Sunday in particular I was there

when several respectable women were also there -- relatives of those I

went to see. When the time for leaving the prison arrived we came in a

body of nine or ten persons into a large yard which we had to cross --

into this yard a number of felons were admitted and they were in such a

condition that we were obliged to request the jailer to compel them to

tie up their rags so as conceal their bodies which were most indecently

exposed and was I have no doubt intentional to alarm the women and

extort money from the men. When they had made themselves somewhat decent

we came into the yard, and were pressed upon and almost hussled by the

felons whose arms and voices demanding money made a frightful noise and

alarmed the women. I who understood these matters collected all the

halfpence I could and by throwing a few at a time over the heads of the

felons set them scrambling swearing all but fighting whilst the women

and the rest made their way as quickly as possible across the yard."

(British Library, Add. MS. 27,826, Place papers. Vol.XXXVIII: Manners

and Morals, vol.II', fol.186)

The pillory at Charing Cross: hand-coloured aquatint printed by John Bluck after drawing by Thomas Rowlandson and Augustus Pugin for Ackermann's Microcosm of London, 1809

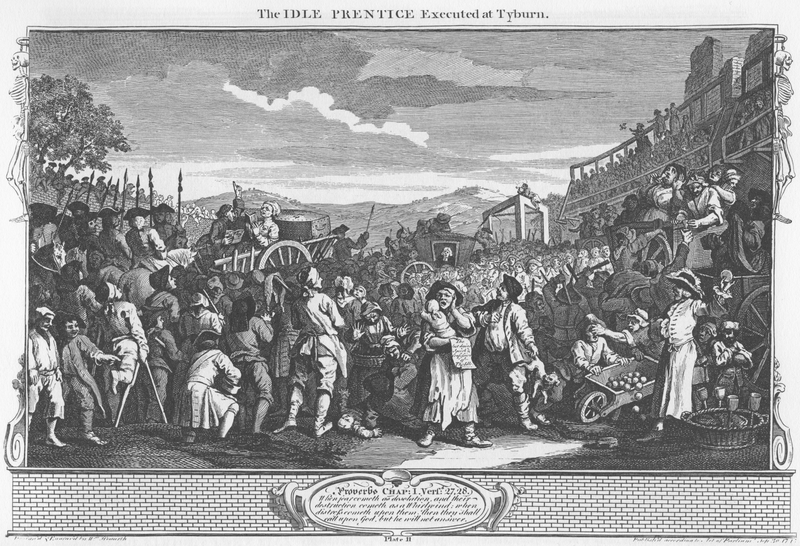

The permanent gallows at Tyburn, which stood where Marble Arch now stands. Executions at this site necessitated a three-mile cart ride in public from Newgate prison to the gallows. Huge crowds collected on the way and followed the accused to Tyburn. These were used as the gallows for London offenders from the 16th century until 1759. Note the size of this structure: about 4 metres tall, it was capable of hanging nine people at a time. The victim was led up to the gallows on a cart, put in the noose and the cart driven away, Here Jack Sheppard, aka "Gentleman Jack", notorious thief and multiple escapee, and allegedly the "original" of John Gay's Captain Macheath in The Beggar's Opera, was hanged 16 November 1724: author unknown, c. 1680 (UK National Archives)

The Idle Prentice executed at Tyburn: William Hogarth (1697-1764), plate 11 in Industry and Idleness (from Hogarth's Graphical Works)

Execution Day at York: Thomas Rowlandson, c. 1820 (York Art Gallery)

The manner of execution at Tyburn: author unknown, late 17th century

The Beggar's Opera: Air LXVII ("Since laws were made")

ReplyDeleteWe're never wholly done with class over here (for all Tony Blair's sentimental chatter): it's our great rich seam and our curse.

ReplyDeleteThe reprieve gives me great pleasure:

"All this we must do, to comply with the Taste of the Town"

Empson is spot on. The true critic must always tread delicately along the wire fence at the border.

Swift’s perspicacity and rapier wit has, in my opinion, no parallel today. He cuts to the heart of meanings and intentions that perhaps, only Plato/Socrates could reveal, meaning by meaning as to the whys and uses of the various archetypes found in theater and literature. Swift’s plumbing of art as a social and political safety net adds to the what lies behind bread and circus’s, how the status quo can be preserved, have its toxic blood let, yet entertain and for the discerning, educate and transcend amusement.

ReplyDeleteA dose of Swift is marvelous for the brain…Thank you TC.

WB,

ReplyDeleteSo glad you liked this; reading the Opera again lately, I found it quite wonderful, and was left dazzled by its genre-bending qualities, its merciless skewering of hypocrisy, avariciousnes and pomposity at all levels and in all nooks and crannies of the human "spectacle".

There is a great -- and obviously deliberate, this is the art of the thing -- blurring of borders in the Opera, as though that invisible wire fence between the classes had become tangled, so that the frontier between "high" and "low" moral and political values becomes impossibly (and hilariously) confused, and everything that is said seems to imply something else, quite often its opposite. Some of the period satire involves politics (the Whig PM, Walpole, paired with a comparable arch-manipulator, Peachum) and style (the rage in London for Handelian operatics, which the play exposes), but these references appear now to comprise the furniture of the piece, topical bits of joke overlaid upon its underlying structure.

Parallels between the opposed social classes are often presented in ways that would have seemed sharp, even embarrassing to some at the time. This shock effect along with the exuberant fun of the thing combined to make the play so successful that Handel was driven off the London stage for a whole season by Gay's triumph.

All these centuries later however the thrust and point of the play remain unblunted. To show that roguery reigns equally on both sides of the social no man's land, with the most powerful rogues on either side enjoying their successes at the expense of everybody else -- and only those of the "low" side ever getting caught out, due to something (something, we are shown, about human nature) built permanently into this terrible equation -- this achievement of Gay's seems at least as pertinent in 2012 as it would have in 1728.

The Beggar's Opera was the first of the ballad operas to hold the stage beyond the end of the eighteenth century, and in the nineteenth it developed into musical comedy. Some at the time thought Gay had got the idea from Addison's curious production Rosamund (1707). But Bonamy Dobrée, who was a close scholar of the period, wrote in 1959 as follows:

"...'Whether this new drama [of Gay's] was the product of judgement or of luck' as Dr Johnson was to comment, 'the praise of it must be given to its inventor'. And it had in it, as recent revivals suggest, the elements of permanence, because although human value are reversed, they exist by implication, and serve as a basis for the apparently careless grace and wit of the whole enchanting and virile performance. How far play-goers can be aware of what Gay is actually doing with them is doubtful: the 'double-irony' method, out of which the jokes are constructed, is inherent in the whole movement of the story', as Professor Empson analyses it in his brilliant study, and the method takes a little time to penetrate; the actors seem to say one thing while actually implying its contrary; delightful shocks are administered to moral sensibility; Macheath can come out with such a Senecan 'sentence' as

A moment of time may make us unhappy for ever;

and the underlying grimness itself stimulates the gaiety, which is sometimes of a weighty order. It is a serious criticism of society delivered as a light-hearted jest."

Artemisia,

ReplyDeleteSorry to have missed yours till I'd replied to the previous. But yes, Swift is certainly relevant here. It's thought he planted the idea for the Opera in Gay's mind; that would make sense; and in the end there came a brilliant harvest.

These days there is little taste for writers with these rapier skills; indeed, these days, the exercise of such skills would surely prove career-threatening; and skills that are not used can never have been developed; which is unfortunate, for we live in a society that at times seems to beg to be addressed not with kid-gloves fondness but upon the tines of a barbecue fork.

By the by, it's long seemed to me that a small bit of characteristically disarming self-memorializing Gay left behind to be remembered by might well serve equally for many a much less gifted writer:

ReplyDeleteMy own Epitaph

Life is a jest; and all things show it,

I thought so once; but now I know it.

RHETORICAL QUESTION

ReplyDeleteRapier skills as in rapier wit?

Alas, no point in asking

If parried by dullard,

Fencesitting dimwits.

Teachers are beggars in the Opera

ReplyDeleteoften the only ones in town

with jobs

from the state

theater of middle management

too much time

too much blood

on hands

wringing out

the results

from the newest

newly-laundered

exam

instead of strangling

little necks

as would seem proper

given this ongoing

paradox.

Sing it out, teachers

make the song loud

make it endless.

Venn Diagram: Kafka vs. Hitler

ReplyDeleteIn the middle

Is the need for shelter

From the surreal body

One moves outside the circle

Against the rules

One moves closer

To the middle

Of his circle the edge

Too mossy and fertile

Human humiliating

One keeps disappearing

Like he was not there

Anonymous

They both wanted

The mundane to be left alone

At the end. To do whatever.

We cannot stop thinking about them

About their fears

One was Ferdinand the Bull

One pretended to be

One dreamed of moss

One of modern convenience

Of which he was used

Mundane chores

Both were already in the future

About the paradox—

One left the diagram

Completely

Forced into

The number line

O teacher, o little lamb teacher

ReplyDeletepublic school teacher

fluffed up for the slaughter

for the sacrifice

of the test

that everyone cheats on--

are you now in your

little bunker

waiting for the end?

I see the mini-fridge

you desired

thought of in your widowhood

and the plug-in kettle

for java

who could not do without

these modern conveniences

in a modern classroom

as you wait

for the final bell

like a comfortable mummy

all wrapped up

in a cozy cardigan

despite the heat

reading about your husband

Mr. Franz Kafka.