.

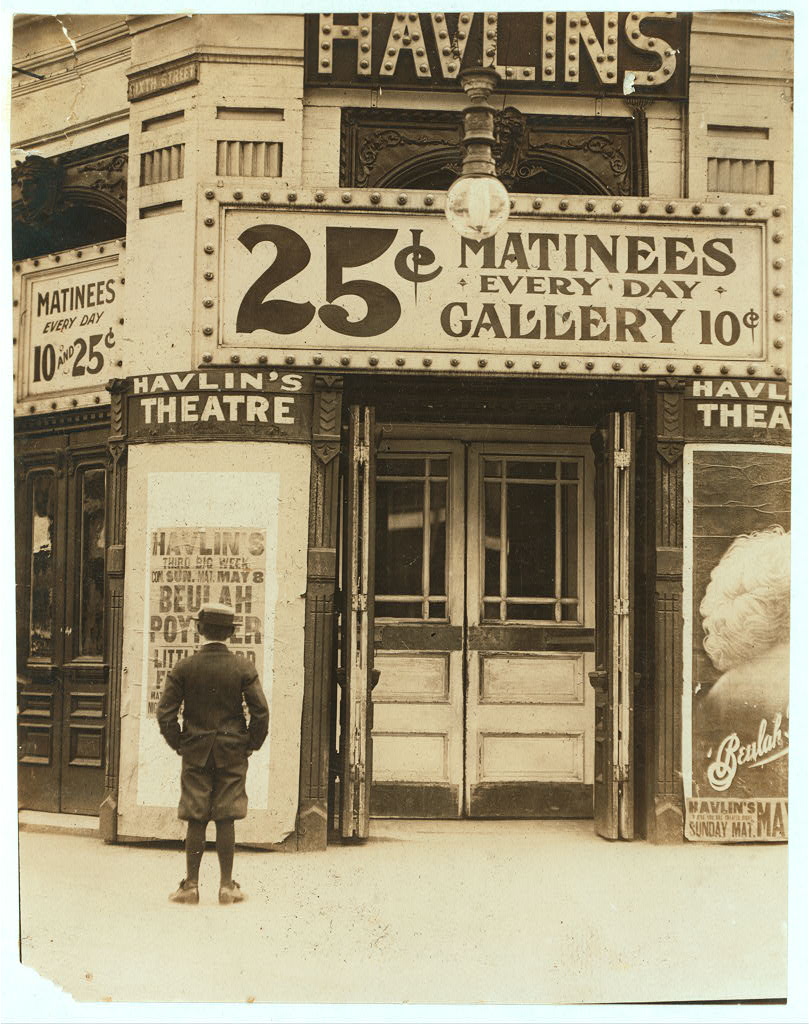

Where the boys spend their money. St. Louis, Missouri: photo by Lewis Wickes Hine (1874-1940), May 1910 (National Child Labor Committee Collection, Library of Congress)

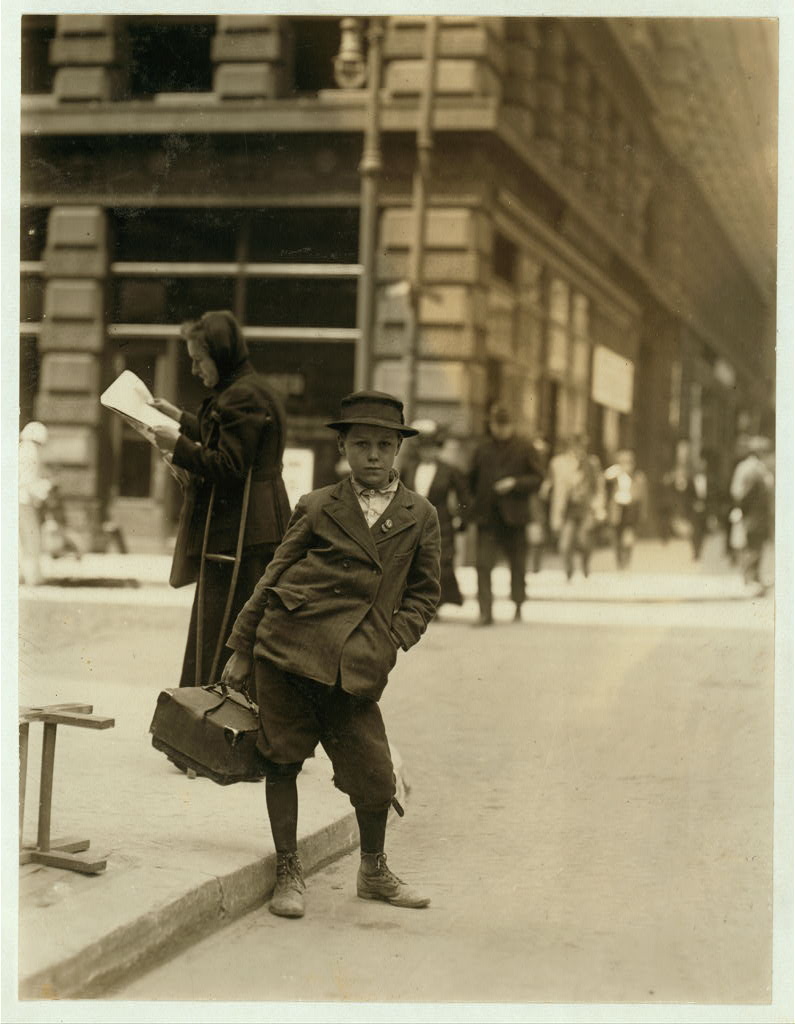

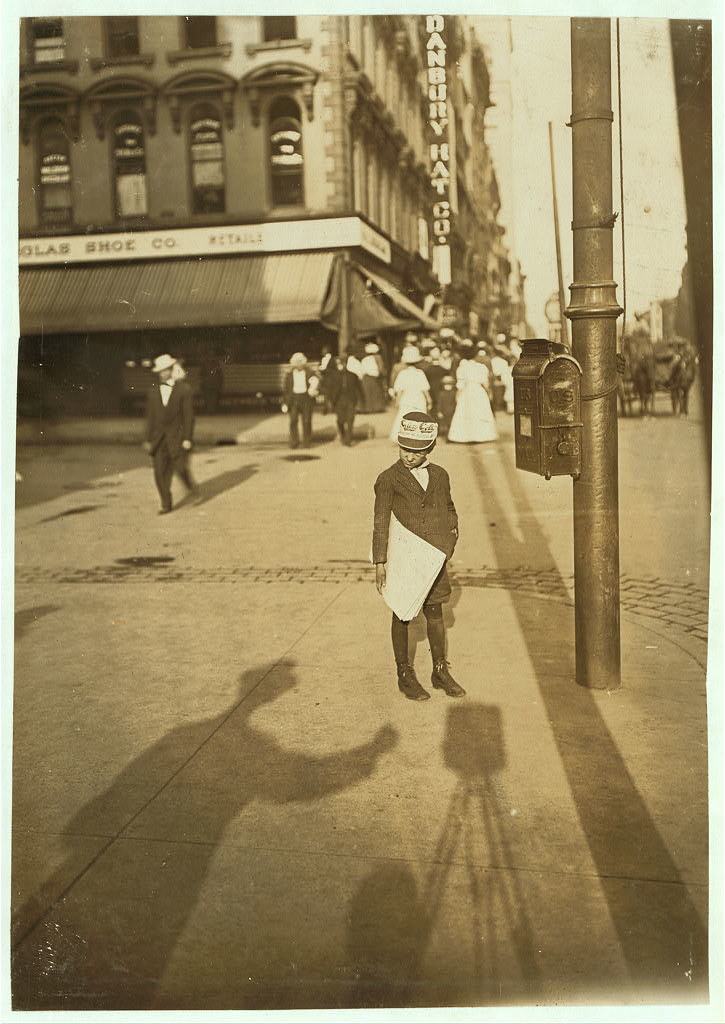

Bundle boy. St. Louis, Missouri: photo by Lewis Wickes Hine (1874-1940), May 1910 (National Child Labor Committee Collection, Library of Congress)

Bootblack, City Hall Park, New York City: photo by Lewis Wickes Hine (1874-1940), 25 July 1924 (National Child Labor Committee Collection, Library of Congress)

5:00 A.M., Sunday. Newsboys starting out with papers from McIntyres Branch, Chestnut and 16th Streets, St. Louis, Missouri: photo by Lewis Wickes Hine (1874-1940), 8 May 1910 (National Child Labor Committee Collection, Library of Congress)

Group of Breaker Boys in #9 Breaker, Hughestown Borough, Pennsylvania Coal Company. Smallest boy is Angelo Ross. Pittston, Pennsylvania: photo by Lewis Wickes Hine (1874-1940), January 1911 (National Child Labor Committee Collection, Library of Congress)

Street gang, corner Margaret and Water Streets, 4:30 P.M., Springfield, Massachusetts: photo by Lewis Wickes Hine (1874-1940), 27 June 1916 (National Child Labor Committee Collection, Library of Congress)

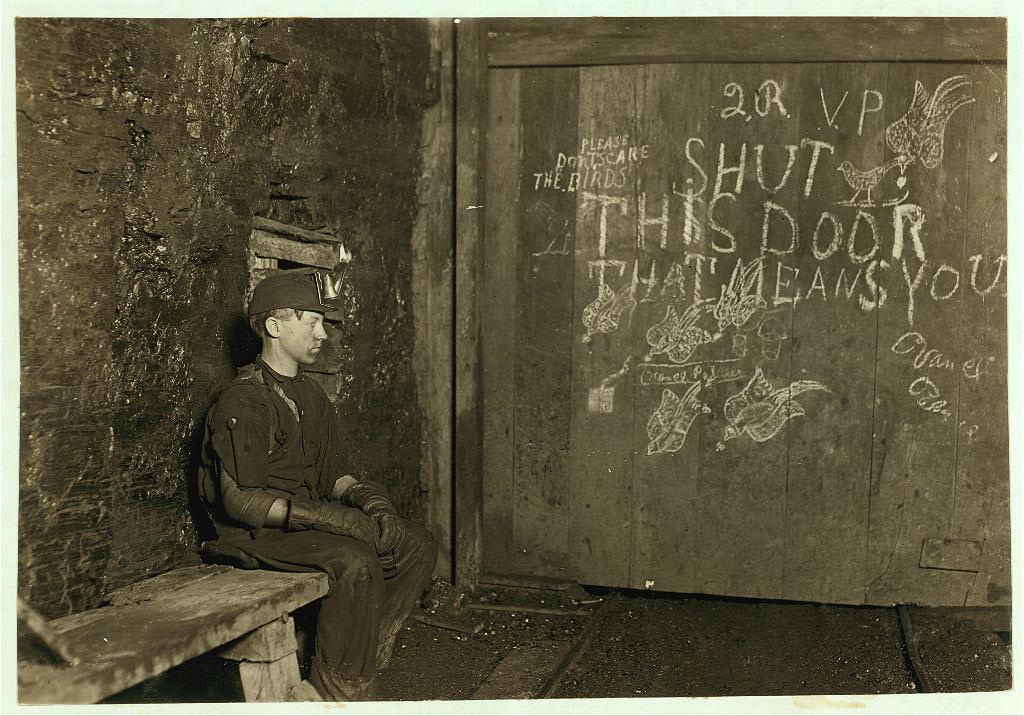

Vance, a Trapper Boy, 15 years old. Has trapped for several years in a West Virginia coal mine at a wage of $.75 a day for 10 hours work. All he does is to open and shut this door: most of the time he sits here idle, waiting for the cars to come. On account of the intense darkness in the mine, the hieroglyphics on the door were not visible until plate was developed: photo by Lewis Wickes Hine (1874-1940), September 1908 (National Child Labor Committee Collection, Library of Congress)

Eagle and Phoenix Mill, Columbus, Georgia. "Dinner-toter" waiting for the gate to open. This is carried on more in Columbus than in any other city I know, and by smaller children. Many of them are paid by the week for doing it, and carry, sometimes, ten or more times a day. They go around in the mill, often help tend to the machines, which often run at noon, and so learn the work. A teacher told me the mothers expect the children to learn this way, long before they are of proper age: photo by Lewis Wickes Hine (1874-1940), April 1913 (National Child Labor Committee Collection, Library of Congress)

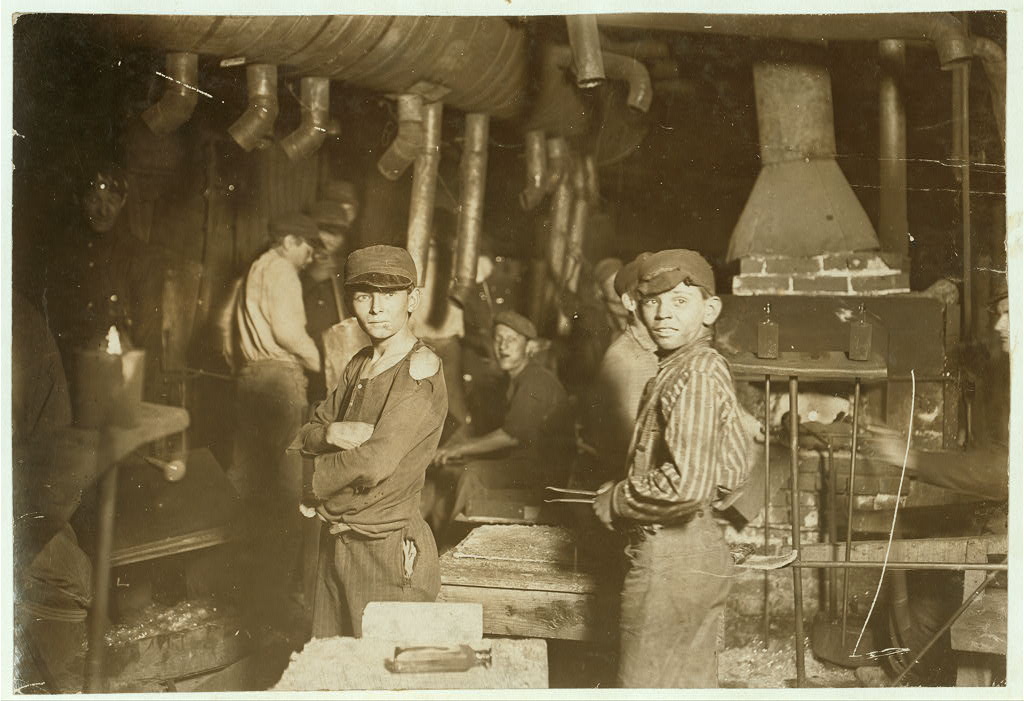

Glass works, midnight, Indiana: photo by Lewis Wickes Hine (1874-1940), August 1908 (National Child Labor Committee Collection, Library of Congress)

A Little "Shaver". Indianapolis Newsboy, 41 inches high. Said he was 6 years old. Witness, E. N. Clopper. Indianapolis, Indiana: photo by Lewis Wickes Hine (1874-1940), August 1908 (National Child Labor Committee Collection, Library of Congress)

John Howell, an Indianapolis newsboy, makes $.75 some days. Begins at 6 a.m., Sundays. Lives at 215 W. Michigan Street. Indianapolis, Indiana: photo by Lewis Wickes Hine (1874-1940), August 1908 (National Child Labor Committee Collection, Library of Congress)

Fruit Vendors, Indianapolis Market. Witness, E. N. Clopper. Indianapolis, Indiana: photo by Lewis Wickes Hine (1874-1940), August 1908 (National Child Labor Committee Collection, Library of Congress)

Manuel, the young shrimp-picker, five years old, and a mountain of child-labor oyster shells behind him. He worked last year. Understands not a word of English. Dunbar, Lopez, Dukate Company. Biloxi, Mississippi: photo by Lewis Wickes Hine (1874-1940), February 1911 (National Child Labor Committee Collection, Library of Congress)

Amos is 6 and Horace 4 years old. Their father, John Neal is a renter and raises tobacco. He said (and the owner of the land confirmed it) that both these boys work day after day from "sun-up to sun-down" worming and suckering, and that they are as steady as a grown-up. Albaton, Warren County, Kentucky: photo by Lewis Wickes Hine (1874-1940), 19 August 1916 (National Child Labor Committee Collection, Library of Congress)

Lunch Time, Economy Glass Works, Morgantown, West Virginia. Plenty more like this, inside: photo by Lewis Wickes Hine (1874-1940), October 1908 (National Child Labor Committee Collection, Library of Congress)

Messenger boy working for Mackay Telegraph Company. Said fifteen years old. Exposed to Red Light dangers. Waco, Texas: photo by Lewis Wickes Hine (1874-1940), September 1913 (National Child Labor Committee Collection, Library of Congress)

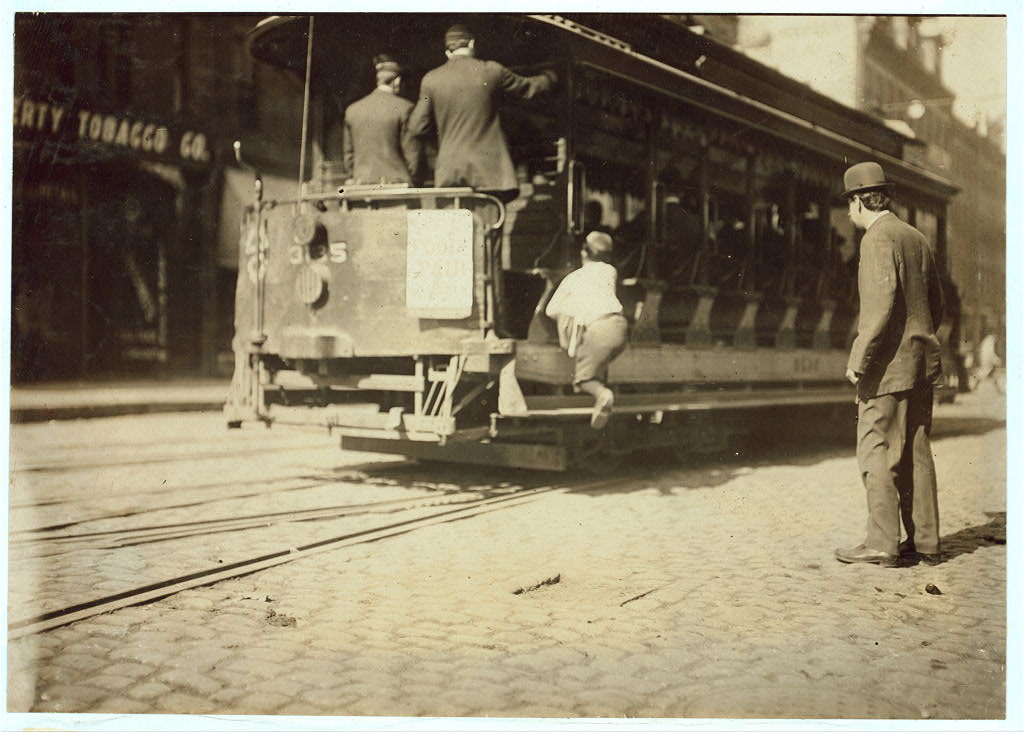

Newsie, "flipping cars". Boston, Massachusetts: photo by Lewis Wickes Hine (1874-1940), October 1909 (National Child Labor Committee Collection, Library of Congress)

Boys picking over garbage on "the Dumps." Boston, Massachusetts: photo by Lewis Wickes Hine (1874-1940), October 1909 (National Child Labor Committee Collection, Library of Congress)

Young Cigarmakers in Englehardt and Company, Tampa, Florida. These boys looked under 14. Work was slack and youngsters were not being employed much. Labor told me in busy times many small boys and girls are employed. Youngsters all smoke. Witness, Sara R. Hine. Tampa, Florida: photo by Lewis Wickes Hine (1874-1940), January 1909 (National Child Labor Committee Collection, Library of Congress)

Brown McDowell, 12 year old usher in Princess Theatre. Works from 10 A.M. to 10 P.M. Can barely read; has reached the second grade in school only. Investigator reports little actual need for earnings. Birmingham, Alabama: photo by Lewis Wickes Hine (1874-1940), October 1914 (National Child Labor Committee Collection, Library of Congress)

Shooting craps. Providence, Rhode Island: photo by Lewis Wickes Hine (1874-1940), November 1912 (National Child Labor Committee Collection, Library of Congress)

Morris Levine, 212 Park Street. 11 years old and sells papers every day -- been selling five years. Makes 50 cents Sundays and 30 cents other days. Burlington, Vermont: photo by Lewis Wickes Hine (1874-1940), 17 December 1916 (National Child Labor Committee Collection, Library of Congress)

A 9 year old boy, Jo Cafarella, 39 Warren Street, Somerville, Massachusetts. His sister Lena, 10 years, and Mary Lazzaro, 13 years old, his cousin, live at 17 South Street. This is typical of their work. Very few boys work on crochet, but he has for 2 years: photo by Lewis Wickes Hine (1874-1940), August 1912 (National Child Labor Committee Collection, Library of Congress)

Pin boys in Les Miserables Alleys. Frank Jarose, 7 Fayette Street, Mellens Court, said 11 years old, made $3.72 last week. Joseph Philip, 5 Wall Street, said 11 years old, and works until midnight every week night; said he made $2.25 last week and $1.75 the week before. Willie Payton, 196 Fayette Street, said 11 years old, made over $2 last week, works there every night until midnight. Lowell, Massachusetts: photo by Lewis Wickes Hine (1874-1940), October 1911 (National Child Labor Committee Collection, Library of Congress)..

lovely boys...a great wordless poem !!

ReplyDeletelooks very much like my North East of the 1950's

ReplyDeleteD.C.

just change the knickers to Roebucks

and you got my UTE I even had a shoe-shine box

just like area north-east of Union Station all the way out towards the Atlas Theater up on about 12 th & H Streets

more black kids than seen in your photos...

now ? that area has been BIG TIME gentrified... the shacks now selling to MOSTLY whit UPPIES for

$ 1/2 Mill and up !

next step in this process ? ignore & obliterate the poor and the old folks... the people who know how to do things and how to survive like rats in the sewer-system !

Sandra, muchas gracias.

ReplyDeleteTal vez esto sea de su interés:

Lewis Hine: Periodismo Global: la otra mirada

muchas gracias Tom...es muy interesante...y tenemos que repetir "una foto puede decir más que mil palabras"

ReplyDeleteWhen I finally got shoes

ReplyDeletethey made noise

I made sure of that

kept them

fancy.

I chose the mountains

over the streets.

Those days like that

so much walking

thousands of miles.

I did not want to be a convict.

ReplyDeleteThose striped

clothes. The work

I was used to.

The words

imaginable

with no shoes.

She was used to slave work

ReplyDeletewanted America

to forget this past

only it was not this

once she got here.

Still, she forgave them

for putting her through

endless abandonment of choice.

She would never fit into

small landscapes of conformity

she thought she left far behind.

There they were: headlines.

Rafael Díaz Arias, over at Periodismo Global (following your link, Tom), notes that Hine’s purpose was not to inform but to re-form, ‘to make the world lest unjust.’ Scarcely a hundred years on, Díaz adds, we’ve reverted to the very world that Hine denounced in photographs, so clear and straight-ahead that we cannot doubt what we are seeing, nor doubt the urgency to act. But, of course, there are always those who cannot really see anything because they cannot feel anything. This is no mere character disorder; this is sociopathy. Such people have turned language on its head and perverted thought and reason: today, Díaz points out, to reform means to destroy the very institutions created to aid and protect those who are vulnerable. The consciousness of this country, if we could speak of such a thing, is becoming a sclerotic consciousness. What fascists demand today is a counter-reformation. Around the US, people with pronounced sociopathic tendencies, some of them vying for public office, announce that they want to abolish the protections afforded children under child labor laws; they want to execute (their term) both rebellious children as well as the parents of illegitimate children. These deliberately-orphaned children, they claim, would then be put up for adoption. More likely, they would be put to work as wards of corporate parents, who, by another contortion of logic, are now real persons.

ReplyDeleteSo poignant it leaves one speechless.

ReplyDeleteFrom the newsboys to the breaker boys is a terrible jump.

ReplyDeleteLewis Hine, a tremendous documenter of American reality, suffered the general dwindling of interest in his work in the 1930s, and died broke. Overdoses of truthfulness have often proved fatal to artists in this country.

ReplyDeleteThanks to Hazen for considering the Rafael Díaz Arias article, a useful view from outside the pale.

Díaz Arias, as Hazen says, "notes that Hine’s purpose was not to inform but to re-form, ‘to make the world lest unjust.’ Scarcely a hundred years on, Díaz adds, we’ve reverted to the very world that Hine denounced in photographs, so clear and straight-ahead that we cannot doubt what we are seeing, nor doubt the urgency to act. But, of course, there are always those who cannot really see anything because they cannot feel anything. This is no mere character disorder; this is sociopathy. Such people have turned language on its head and perverted thought and reason: today, Díaz points out, to reform means to destroy the very institutions created to aid and protect those who are vulnerable..."

At the same I felt that Sandra was right on the mark in suggesting this Lewis Hine set makes a "wordless poem", there also lingered the sense that each of these shots could deserve a poem of its own.

But this old car-battered codger needs a post to lean up against any more... so was very grateful to our brilliant poet friend Vassilis for picking up the flickering torch of the memory of one small nameless tyke from another century, and taking it to the finish line:

Little "Shaver" (Paper Boy), August, 1905

Barefoot, leaning

Back against gigantic candy-

Striped barber pole,

Says he’s six years old, all of

Forty-one inches high, the paper he’s holding

That takes up half his frame holds

All the news you’d want to know.

__

I found particular poignancy in Lewis Hine's choice of "high" as a descriptive term in his caption, eschewing "tall". The Little Shaver may have a (minimal) bit of height (length) -- but of tallness, none at all.

The "stunted growth" of the poor, malnutrition hand in hand with impoverishment, tells a tale that would be lost on today's armies of screaming brats in devil, angel and witch costumes, being herded about the neighborhoods of a doomed nation by overprotective, often comfortably overweight parents, chauffeuring the greedy candy-grubbing hordes from door to door.

Trick or treat... or trick and trick!

The boy in the top shot, by the way, is ogling the billboards of Havlin's Theatre in St. Louis, perhaps considering whether the advertised show is worth his last hard-earned dime (gallery rate). Havlin's was a vaudeville house at Sixth and Walnut (the site is now home to the St Louis Cardinals). The actress and writer Beulah Poynter (1886-1960) was a native of St. Louis, and her company of players opened their "season of stock" in that city on 24 April 1908. Two weeks later, on 8 May, Poynter's "new and original" version of Little Lord Fauntleroy (in which, naturally, she played a leading role), had its first performance. As Lewis Hine gives that date for the photo, it would seem the play's St. Louis run was opening with that day's Matinee.

ReplyDeleteFor those born less than a century ago, "Little Lord Fauntleroy" may not be the household phrase it once was. In this classic rags-to-riches (fairy) tale, the youthful hero, Cedric, lives with his widowed mother in New York City in semi-genteel poverty until it is discovered, by way of a surprising visit from an English lawyer, that there is aristocracy in the family; Cedric is now Lord Fauntleroy and heir to an Earldom and a vast estate. The claim is contended by a dastardly pretender, but, with the assistance of his loyal New York City friends, especially a bootblack named Dick (see the third photo here for a possible Dick, on a bad day), justice prevails, Cedric's mom gets to move into the ancestral castle, while our Cedric (Little Lord Fauntleroy), stays on in America, becoming iconic.

Frances Hodgson Burnett's novel Little Lord Fauntleroy was serialized in St Nicholas magazine in 1885-6 and became a huge hit, the Harry Potter of its epoch. Since that time there have been no fewer than eight film adaptations.

The fashion statement seeded in the story outlasted its deus ex machina drama. The Lord Fauntleroy outfit, visualized in Burnett's prose and in Reginald Birch's detailed pen-and-ink drawings (a velvet cut-away jacket and matching knee pants worn with fancy blouse and large lace or ruffled collar), instigated a vogue for exaggerated formal dress among American children:

"What the Earl saw was a graceful, childish figure in a black velvet suit, with a lace collar, and with lovelocks waving about the handsome, manly little face, whose eyes met his with a look of innocent good-fellowship."

The doting mothers of small male children of the upward-mobile American middle classes fell for this fancy-boy look like the proverbial ton of bricks.

In my childhood, "Little Lord Fauntleroy" was a mildly derisive term applied to any lad who betrayed a bit of the priggish or prissy -- approximately synonymous with "mother's boy". The effeminacy connotation was clear enough to create interesting humouresque effects in having the role played by Mary Pickford in the extremely popular 1921 film version:

"You curly headed sissy!"

One may presume the lad in Lewis Hine's photo was not being groomed for pseudo aristocracy. Still those are doubtless his best Saturday duds, and that is a spiffy straw boater.

"These are sweet-bitter pics of boys," comments Prince Andrei Codrescu back-channel, "-- Romney might take us right back to child labor, some sad faces."

ReplyDeleteThanks for these extraordinary photos, Tom. It's easy to see why life expectancy was so brief not so long ago.

ReplyDeleteTerry,

ReplyDeleteThat's of course the first thought one has, seeing these sad little starveling faces. The sight seems to have compelled Lewis Hine to commit his energies and skills to the remarkable (and largely singlehanded) campaign to amount the documentary evidence that in the end, did bring about the institution of child labor laws -- which are taken for granted now, but seemed novel back then.

My grandfather (that Kerryman) worked in the streets as a lamp lighter before the age of ten, drove a Chicago streetcar at fourteen, yet later on never complained about these things. Indeed his reminiscences of those early labors were intended to impress upon his comparatively far less enterprising grandson the importance of hard work as a qualification for manhood.

Now I hear from the CBS radio morning news that kids spend some incalculably large proportion of their time on Smartphones arranging "casual" sexual encounters. One anonymous teenager, interviewed, shrugged, "Yeah, but, y'know, it's kinda like work, in a way."

Dear T: I think it's difficult to grasp, if you've never done it, how hard physical work can grind you down. I did 5 summers as a construction laborer, starting at age 17, and the experience left a permanent impression on me, even though I knew I wouldn't have to stay stuck there with the pick & shovel the rest of my life. Give me a casual sexual encounter any day. When Gingrich proposed that poor kids be made to clean their schools' bathrooms, I wanted to send him off to a year of backfilling ditches.

ReplyDeleteTerry,

ReplyDeleteHey, I'll have one of those too. Just hand me my crutch.

At sixteen I went into the noble profession of crowd control as an usher for the big ushering syndicate in Chicago (that syndicated town), working everything from wrestling to church dances, roller derby to racetrack, fights, the several and various ballparks & c. I never really thought of it as physical labour until one steamy night at a church dance on the South Side a brick came flying through the air and I had to perform the one act I would ever be any good at -- duck. It hit the guy standing next to me. For a few weeks he had a great livid red rectangle imprinted in his forehead (the mark of the Beast). His usher cap only partially concealed the damage. At that age and stage there was perhaps never really any pain.

But that ol' Newt, now there was a guy for hard work. Where is he now that we need him?

Towering over tall buildings in an oversize sailor suit, last I heard.

Some years back, when it seemed like he might turn out to be a major contender, I devoted this small Ode to his incipient puffly flopply hot-air-and-bluster-filled stay-puft cult.

The state of the union

is the dysfunction

of the nation

and we'd all better

hide our heads

under our beds

if those godsent

red necks

elect

the angry stay puft marshmallow man!

Tom: You've definitely got an eye for Newt.

ReplyDeleteI was wondering if extraneous or other photos taken by Hine ever show up on the market? I was also wondering who might be considered current authorities on Hine's career?

ReplyDeleteI have a photo positive, silver-gelatin, that has the appearance of a Hine photograph. Can anyone out there place Hine in a blueberry field with children pickers?

My fav is the John Howell/ Indy shot because we view the photographer by his shadow. We can also see his technique of holding the shutter release. The tube is very clear amid the texture of the environment.

\No comments for four years? I am not Jim Jones, that is AKA Google. I am Dave