.

Diplomatic letter from Burra-Buriyash of Babylon to Naphurareya (Akhenaten) (r. 1352-1336 BC), the heretic pharaoh who founded a new capital at Tell El-Amarna: clay cuneiform tablet, front; written in complicated Babylonian; corners are broken. Length: 5.25 inches. Width: 2.75 inches. From The Amarna Letters, 14th c. BC, found at Tell El-Amarna, Upper Egypt (Middle East Department, British Museum)

Approximately ten years ago I began to first shyly and reverentially sketch out in pencil everything I produced, which naturally imparted a sluggishness and slowness to the writing process that assumed practically colossal proportions. This pencil system, which is inseparable from a logically consistent, office-like copying system, has caused me real torments, but this torment taught me patience, such that I now have mastered the art of being patient [. . .]

This pencil method has great meaning for me. The writer of these lines experienced a time when he hideously, frightfully hated his pen, I can’t begin to tell you how sick of it he was; he became an outright idiot the moment he made the least use of it; and to free himself from this pen malaise he began to pencil-sketch, to scribble, fiddle about. With the aid of my pencil I was better able to play, to write; it seemed this revived my writerly enthusiasm. I can assure you (this all began in Berlin) I suffered a real breakdown in my hand on account of the pen, a sort of cramp from whose clutches I slowly, laboriously freed myself by means of the pencil. A swoon, a cramp, a stupor -- these are always both physical and mental. So I experienced a period of disruption that was mirrored, as it were, in my handwriting and its disintegration, and when I copied out the texts from this pencil assignment, I learned again, like a little boy, to write.

Robert Walser to editor Max Rychner, 1927

The Microscripts by Robert Walser: photo by Ourit, 7 February 2012

Usually I first put on a prose piece jacket, a sort of writer’s smock, before venturing to begin with composition; but I’m in a rush right now, and besides, this is just a tiny little piece, a silly trifle featuring beer coasters as round as plates [. . .]

I know that you are namelessly grateful to me for these few lines. Oh these slice-of-bread affairs! Godful! I feel as if I could continue this report on into all incredulity . . . What else does the infinite consist of other than the incalculability of little dots? When she was handing him a piece of bread like that, she didn't even look at him but rather continued reading her newspaper undisturbed. She gave it to him utterly mechanically. That's what was so wonderful about it, the part that cannot be surpassed, the way she gave him the bread utterly, utterly mechanically. The mechanicalness of the gesture is what was so beautiful about it. I have also written this prose piece, I must confess, utterly mechanically, and I hope it will please you for this reason. I wish it pleases you so much it will make you tremble, that it will be, for you, in certain respects, a horrific piece of writing. I did not even groom myself properly in order to write it. This alone should suffice to prevent its being anything other than a masterpiece or masterworklet.

Robert Walser: from Usually I first put on a prose piece jacket: Microscript 190, in Microscripts, translated from the German with an introduction by Susan Bernofsky, New Directions, 2010

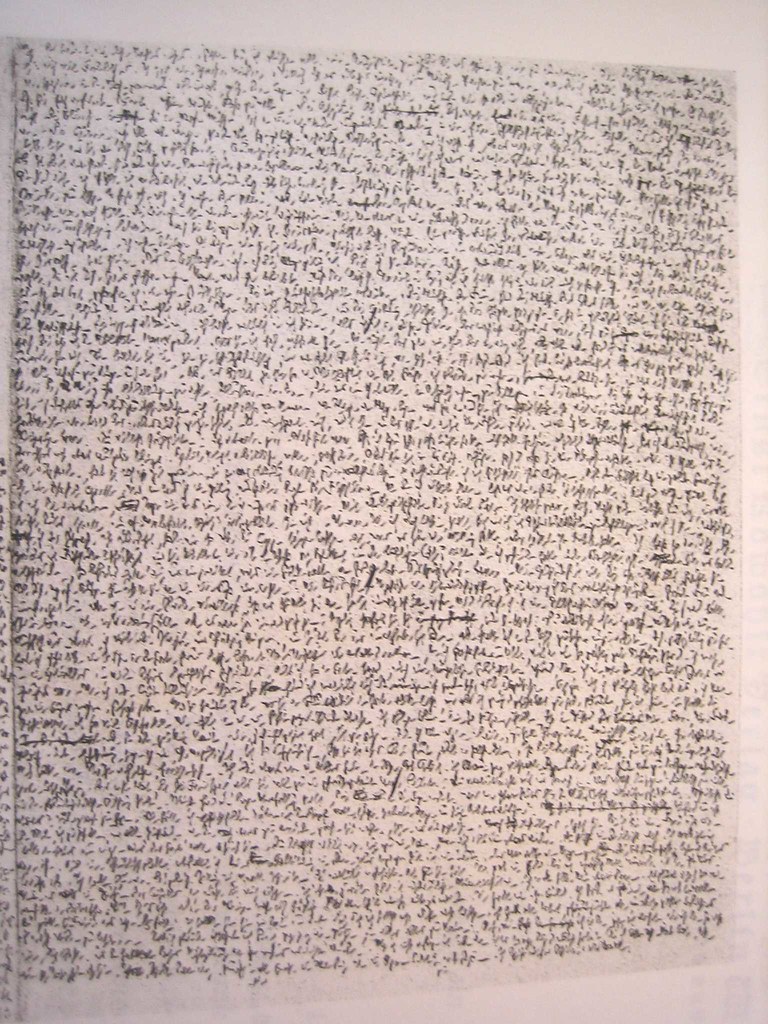

Robert Walser Microscript #1. A Walser manuscript page. Bernhard Echte gave me a copy of this page

when I visited the Walser archive in Zurich. Echte and Werner Morlang spent many years transcribing these pages into readable German: image by Sam Jones, 17 January 2006

Robert Walser Microscript #1 (closeup): image by Sam Jones, 17 January 2006

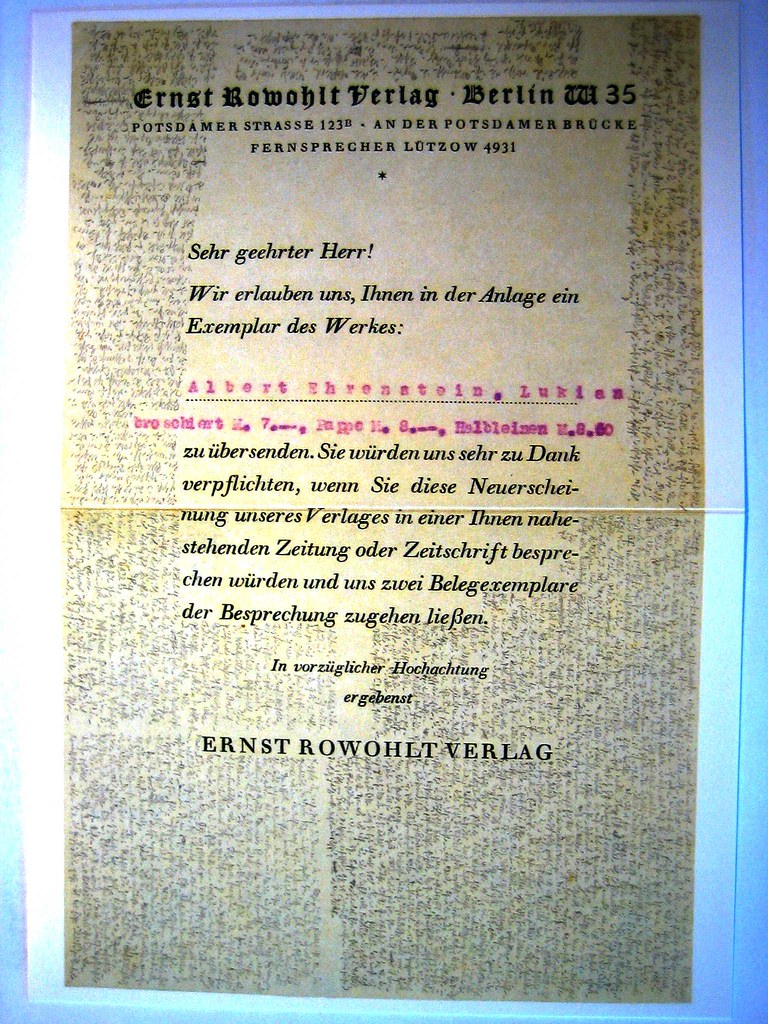

Robert Walser Microscript #2. An image of a notecard I purchased at the Museum Neuhaus in Biel, Switzerland, Walser's birthplace. The legend says "Micrograme No. 147 (Autumn 1925); crayon, 20.5 x 13.2 cm." As I recall, the text consists of a review Walser wrote of the book that accompanied this publisher's announcement: image by Sam Jones, 17 January 2006 (Robert Walser-Archiv, Zurich/Museum Neuhaus, Biel)

Robert Walser Microscript #2 (closeup): image by Sam Jones, 17 January 2006 (Museum Neuhaus, Biel)

Diplomatic letter from Burra-Buriyash of Babylon to Naphurareya (Akhenaten) (r. 1352-1336 BC), the heretic pharaoh who founded a new capital at Tell El-Amarna: clay cuneiform tablet, back; written in complicated Babylonian; corners are broken. Length: 5.25 inches. Width: 2.75 inches. From The Amarna Letters, 14th c. BC, found at Tell El-Amarna, Upper Egypt (Middle East Department, British Museum)

Tom,

ReplyDeleteEach letter in its place -- how writing gets written -- these images of cuneiform tablets next to Robert Walser's microscript pages.

11.12

light coming into sky above still black

ridge, moon below planet by pine branch

in foreground, sound of wave in channel

blue faded an ordinary blue,

green and orange door

a place in which each being,

position, is possible

cloudless blue sky reflected in channel,

shadowed green slope of ridge across it

And beyond that ordinary blue, behind that green and orange door:

ReplyDeleteRobert Walser: This life, how old it is

Walser is an interesting author...I like his style ...a mixture of naiveness and honesty...

ReplyDelete"I learned again, like a little boy, to write."

ReplyDeleteThere's a chance to have! His aching body shows him the way back to the beginning.

The clay tablets - It's interesting to think about these early forms of writing in relation to Akhenaten's prohibition on all images but that of the Sun.

Just thinking about that microscript gives me eyestrain. The translator’s efforts are in the nature of a sacrifice. A ‘masterworklet’ all around.

ReplyDeleteThe miniscule writing made mincemeat out of what it was written on. Like tiny trails of worms in old wardrobes--it made each item more precious, worked, lived. Its value went up as its maker disappeared behind each tiny filigree, flourish, scratch, and scroll. It was art, it was worm-eaten. What did it mean?

ReplyDeleteI love the look of Cuneiform. Always have. Even the word makes me happy.

ReplyDeleteIt's interesting to think about--I also love the term, pen malaise, and am relieved to think others are as interested in the implements of writing as I am, to the point of being obsessed.

"Usually I first put on a prose piece jacket, a sort of writer’s smock, before venturing to begin with composition"

ReplyDeleteI like the notion of dressing before putting pen to paper.

From these acute comments I gather that the obsessive decoration of the writer's smock -- like trails of worms in old wardrobes -- is something that several of us here may be familiar with.

ReplyDelete(If not at least vaguely ashamed about.)

When writing takes on the appearance of unintelligible signs scratched or scored by hand upon material surfaces, we are forced to remember that the distance between such signs and what we might think of as "meaning" is an unbridgeable abyss. There appear to be others some like me who have kept pocket size notebooks, and got into the habit of extremely tiny writing in these, to save space on the small pages. If such marks, like mine, had been made in pencil; and the graphite had been rubbed away with the years, and one's vision had deteriorated concurrently; a return to the pages is likely to discover all trace of meaning gone, suggesting that perhaps the meaning had never really been there in the first place.

A useful response to this book came from reviewer Rivka Galchen in Harper's, 17 September 2010 -- "From the Pencil Zone: Robert Walser's Masterworklets". Galchen's piece concludes with a reference to the story excerpted in the present post, offering a slightly expanded extract from the passage here quoted.

ReplyDelete"Robert Walser was born in Biel, Switzerland, in 1878, into a family of modest means and many siblings, none of whom went on to have children of their own. Through his twenties and thirties Walser published numerous shorts and several novels (admired by Kafka!) and even had a biography written about him, but as the market for shorts dwindled, his career began to decline, he moved through a series of smaller and smaller apartments in less and less pleasant cities, his handwriting diminished in size, and, by 1929, when Walser basically stopped publishing, he was already forgotten. He settled himself into one and then another mental institution, spending the last twenty-seven years of his life in an isolation punctuated by reading the newspaper and long lonely walks.

. . .

"Stable employment of a kind eventually came to Walser, in the role of Crazy Person. Scholarship suggests he wasn't straightforwardly 'crazy' (some doctors encouraged him to try living outside institutional care), but that's another matter. In 1929, Walser was diagnosed with schizophrenia and entered the Waldau sanatorium in Bern, Switzerland. Four years later, his family had him transferred to another sanatorium, closer to their home of Herisau, and he lived out his last twenty-three years there, cared for by the state. It was from that final and steady non-employment that Walser claimed finally to abandon the avocation game altogether, with a line now remarkably famous considering that it comes from the least famous canonical writer: 'I'm not here to write. I'm here to be mad.'

"Whether Walser in fact stopped writing is not quite clear. But we do know that the works of his we have are written on the backs of tear-away calendar pages or on the detached covers of penny dreadfuls and that the writing is in a script so tiny as to be nearly illegible. ...[T]he 526 pages of microscripts that were found after Walser's death ... have been published in Germany in six volumes, under the title Aus dem Bleistiftgebiet, or 'From the Pencil Zone'...) Many of the stories have no titles; some seem to have been abandoned before they were finished; a number of them date from after Walser became a voluntary patient in Waldau, but none are known to date from after the 1933 move to the sanatorium at Herisau.

"Visually, these texts call to mind the laboriousness of a Darger scroll, or the crowded word-clouds and asemic writing of Robert Crumb's tragic brother, Charles. Which is to say: They call to mind genuine madness. Walser's companion and literary executor, Carl Seelig, had seen these writings and assumed that the tiny hatch marks crowding up the scraps of paper Walser carried around were a private code, but one signifying nothing. When Seelig was contacted by a man who claimed to have deciphered a microscript (an enlarged mimeograph of one had run in the journal Du as a sort of artwork), Seelig didn't answer the inquiring letter, and it was Seelig who controlled access to Walser's papers. Arguably, Seelig was the better Brod, keeping the secrets of a writer who clearly wanted to keep secrets -- why else make your writing unreadable and stop sending things out? -- though Seelig may have overlooked the deeper and perennial secret of secret -- keepers: that they don't want to keep secrets at all. 'Such a peculiar vice,' Walser writes in Jakob von Gunten, 'to be secretly pleased to be allowed to observe that one is being slightly robbed.'

[continues]

ReplyDelete"...Walser had long -- even before the asylum -- been writing in Kurrent, the script widely used in his time. A version of a medieval shorthand, Kurrent, which dramatically reduces the number of strokes used to represent each letter, is particularly vulnerable to (or amenable to) becoming nearly inscrutable when made small. And made small it was, with the letters about one to two millimeters tall; Walser was able to fit, for example, six stories on a postcard received from a newspaper editor. The difficulty of reading Walser's script makes it seem like Walser gave up on the writing game even as he was, in fact, writing. It took the team of decoders, Morlang and Echte (names that sound like either characters in a Lovecraft story or the founders of a German cutlery company), much of the 1980s to decipher the microscripts. Looking at ... reprints of the originals ... with their tidy little marks, one gets the sense of a terminal Bartleby, just barely preferring not to prefer not to.

"Walser's methodology -- not quite sleepy, not quite caffeinated, but analogous -- works not just on the level of handwriting, of course. One Walser legerdemain is that of the insignificant subject matter... Walser's technique in this way resembles a Dutch still life: a small and domestic scene, a woman with a water jug, say, and yet there's always a map, the sea out the window, an instrument that comes from a distant shore -- the small domestic scene encompasses the world.

"Walser expands on this Dutch Renaissance trick -- light coming through the window -- in one of the microscripts from 1925, a piece about beer coasters written on the back of an art print and not published in Walser's lifetime. We meet "silly beer-glass mats" that 'were filled with radiant joyousness at seeing themselves employed to playful ends.' The coasters are nothing but also animate; they're insignificant and yet also ecstatic as servants of the Lord. Later in the short, as if panning out, we meet the children playing with the beer mats and the 'overjoyed' dog also present. The text then digresses into a small hostility between a (characteristically) unnamed man and woman. After describing the scene in just a few strokes -- the 'she' indifferently hands the 'he' a slice of bread -- the narrator interpolates: 'I could write you a thirteen hundred page, that is to say a very fat book about this, if I wanted, but at least for the time being I don't want to. Maybe later.' Even Walser's impassioned denyings deny themselves the full force of denial.

"And instead of any actual 1,300-page tome, Walser provides assurances in the selfsame short that he is at his best -- the best servant to the reader -- when he's not himself at all. After the namelessness of the man in the piece is noted to make the man happy -- to be nameless, a kind of invisible, is always a kind of joy not just for Walser but also in Walser; one thinks of Dickinson's 'How dreary -- to be -- Somebody/How Public -- like a Frog' -- the same modesty is attributed to the reader:

[continues]

ReplyDelete"'I know that you are namelessly grateful to me for these few lines. Oh these slice-of-bread affairs! Godful! I feel as if I could continue this report on into all incredulity . . . What else does the infinite consist of other than the incalculability of little dots? When she was handing him a piece of bread like that, she didn't even look at him but rather continued reading her newspaper undisturbed. She gave it to him utterly mechanically. That's what was so wonderful about it, the part that cannot be surpassed, the way she gave him the bread utterly, utterly mechanically. The mechanicalness of the gesture is what was so beautiful about it. I have also written this prose piece, I must confess, utterly mechanically, and I hope it will please you for this reason. I wish it pleases you so much it will make you tremble, that it will be, for you, in certain respects, a horrific piece of writing. I did not even groom myself properly in order to write it. This alone should suffice to prevent its being anything other than a masterpiece or masterworklet, as we would no doubt rather say with forbearance. We wish to give forbearance the upper hand, and isn't it true that you were glad about the late addition of the piece of bread? I most certainly was. I would presuppose the greatest joyfulness on this score, for this is the most important thing, and you must consider it the best. You must without fail be satisfied with me, do you hear? Without fail. And then that little mat. This reality. This treasure trove of in-fact-having-occurred-nesses. This car drove off, and he and she were sitting in the back. How do you like my "trove" and "drove"? Make a note of these words! They're not my invention. How could such delicate expressions have originated with me? I just snapped them up and am now putting them to good use. Don't you think my "trove" is ben trovato? Please do be so good as to think so. Accept my heartfelt greetings and do not forget the pride of that silly little dog. He was adorable.'"