Example of one species of tall grass, Big Bluestem, making a comeback in overgrazed pasture near Troy, Kansas, in Doniphan County in the extreme northeast corner of the state. Conservationists say this area Is unique because it contains the only hardwood forest in Kansas in addition to tallgrass prairie. September 1974

Indian grass grows with the bluestem;

switchgrass also ripples there in the wind.

Going west you get less rain:

the little bluestem grows waist high, and so does

the side oats grama, and the bearded needlegrass.

Further west, the short grass of the Plains grows:

the blue grama, knee high; and the buffalo

grass, which grows up to the ankles.

TC: Grasses, from A Short Guide to the High Plains, 1981

Remnant of the tallgrass prairie which once flourished in the northeast corner of Kansas is seen overlooking the Missouri River from a bluff near White Cloud and Troy, Kansas, in Doniphan County. This area of the state Is unique because it contains the only hardwood forest in Kansas in addition to tallgrass prairie. September 1974

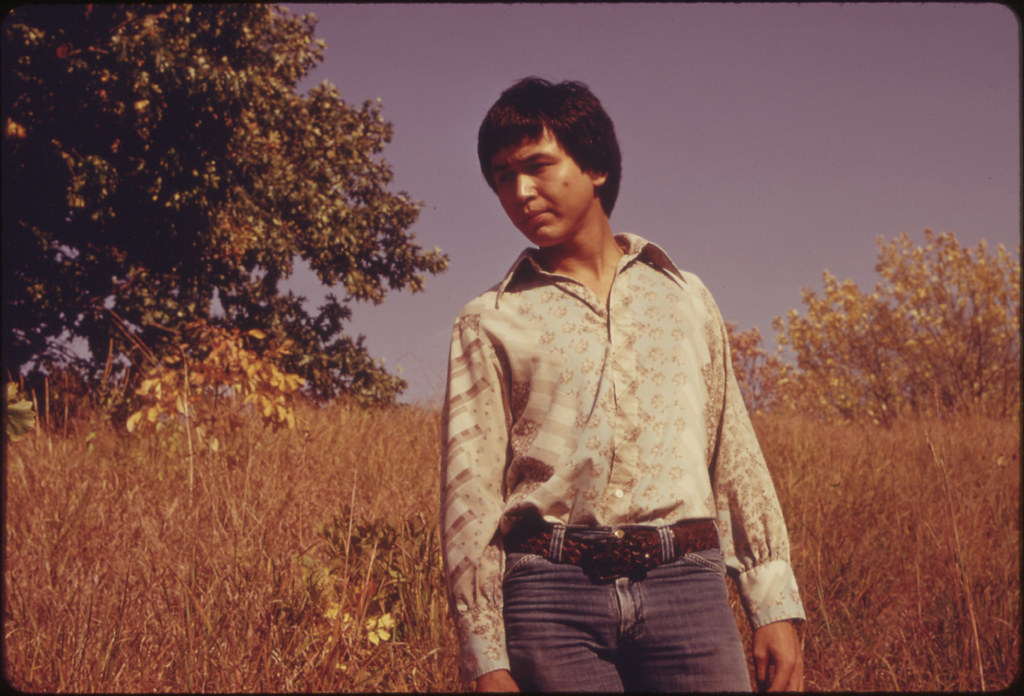

Ron Mckinney, 22, whose Indian name Is Mahkuk, is standing in a virgin tallgrass prairie area near White Cloud and Troy, Kansas in Doniphan County in the extreme northeast corner of the state. The Young Man, a Potawatomie-Kickapoo, lives near White Cloud, which was named for the last great chief of the Iowa Indian tribe. The Indians were given the area land by treaty in 1836. The small town Is located at the edge of the Iowa-Sac-Fox Indian Reservation. October 1974

Flocks of Blue Geese stop at the Squaw Creek National Wildlife Refuge near Mound City, Missouri, at the northwest corner of the state. The Refuge covers approximately 6,000 acres and a major stopover on the Mississippi flyway for migrating shore birds. October 1974

Flocks of migrating Blue Geese and Snow Geese Stop at the Squaw Creek National Wildlife Refuge near Mound City, Missouri, at the northwest corner of the state. October 1974

Cornfield that formerly was open tallgrass prairie near White Cloud and Troy in Doniphan County, Kansas, in the northeast corner of the state. The wave of pioneers cleared the native grasses and planted crops in the fertile soil. As a result only isolated patches of native tallgrass prairie survive. There Is a bill in Congress which would make an area of Kansas a Tallgrass Prairie National Park, but it has been stalled in committee for several years. October 1974

Closeup of tall grasses being taken over by forest and sumac, near White Cloud and Troy in northeastern Kansas. A wave of pioneers cleared the native grasses and planted crops in the fertile soil. As a result only isolated patches of native tallgrass prairie survive. October 1974

Rusted iron hand pump on land which used to be covered by tallgrass prairie in Johnson County, Kansas, near Kansas City. The wave of pioneer farmers cleared the native grasses and planted crops in the fertile soil. As a result only isolated patches of native tallgrass prairie survive. September 1974

Abandoned house and rusted iron hand pump on land which used to be covered by tallgrass prairie in Johnson County, Kansas, near Kansas City. The wave of pioneer farmers cleared the native grasses and planted crops in the fertile soil. As a result only isolated patches of native tallgrass prairie survive. September 1974

Former prairie which Is now farmland in Waubaunsee County Kansas, near Manhattan, in the heart of the Flint Hills region. The county Is one of the sites under consideration for a Tallgrass Prairie National Park. There Is a bill in Congress for such a park, but It faces opposition and has not yet been reported out from committee. January 1975

Former prairie which Is now farmland in Waubaunsee County Kansas, near Manhattan, in the heart of the Flint Hills region. The county Is one of the sites under consideration for a Tallgrass Prairie National Park. There Is a bill in Congress for such a park, but It faces opposition and has not yet been reported out from committee. January 1975

A prairie cemetery in Wabaunsee County, Kansas, near Manhattan, in the heart of the Flint Hills region. Cemeteries are very good places to find the original plants of the tallgrass prairie. January 1975

A prairie cemetery with tall grass growing along the fence in Wabaunsee County Kansas, near Manhattan, in the heart of the Flint Hills region. January 1975

Sunset view of a horse in pastureland that once was tallgrass prairie in Wabaunsee County Kansas, near Manhattan, in the heart of the Flint Hills region. January 1975

Santa Fe Railroad engine on the tracks in Johnson County Kansas, near Kansas City. Tallgrass prairie Is seen in the foreground. The tracks follow the Kansas River along the general route of the early explorers who made trails through the area. Much of the state was tallgrass prairie before the wave of settlers in the last century. February 1975

The Konza Prairie near Manhattan, Kansas. It represents 1,000 acres of virgin tallgrass prairie given to Kansas State University by Katharine Ordway of New York City and Weston, Connecticut through the Nature Conservancy. The prairie Is used primarily for research and Is maintained by periodic burning because there are no large grazing animals on It. August 1974

A view of a portion of Konza Prairie, 1,000 Acres of virgin tallgrass prairie near Manhattan, Kansas. Although the picture was taken in August during a summer of extreme drought, the prairie remains green because Its grass roots grow so deep. The native tall grasses retain 18 times the moisture of cultivated grasses such as wheat, corn and bluegrass. One acre of native tallgrass releases the same amount of moisture as a 70-ton air conditioner. Baldwin's Ironweed, seen in the foreground, Is a common tallgrass prairie plant. August 1974

Closeup of Baldwin's Ironweed, a common tallgrass prairie plant seen on the Konza Prairie, 1,000 Acres of virgin tallgrass prairie near Manhattan, Kansas. Although the picture was taken in August during a summer of extreme drought, the prairie remains green because Its grass roots grow so deep. One acre of native tallgrass releases the same amount of moisture as a 70-ton air conditioner. August 1974

View of tallgrass prairie plants seen on the Konza Prairie. August 1974

View of the Konza Prairie, 1,000 acres of virgin tallgrass prairie near Manhattan, Kansas, in the winter. The mood and look of the prairie changes drastically from season to season. February 1975

View of the Konza Prairie, 1,000 acres of virgin tallgrass prairie near Manhattan, Kansas, in the winter. The mood and look of the prairie changes drastically from season to season. February 1975

View of the Konza Prairie, 1,000 acres of virgin tallgrass prairie near Manhattan, Kansas, in the winter. The mood and look of the prairie changes drastically from season to season. February 1975

View of the Konza Prairie, 1,000 acres of virgin tallgrass prairie near Manhattan, Kansas, in the winter. The mood and look of the prairie changes drastically from season to season. February 1975

View of the Konza Prairie, 1,000 acres of virgin tallgrass Prairie near Manhattan, Kansas, in the winter, showing a typical overcast sky. In the foreground Is Indian Grass, a major prairie tallgrass. February 1975

Tall grasses in winter covered by ice and snow at Lake Quivira, Kansas, near Kansas City. This is a transition area in which the grasses are being crowded out by forest. February 1975

Closeup of tall grass, Big Bluestem, covered with winter ice and snow at Lake Quivira, Kansas, near Kansas City. Such vegetation makes excellent cover for wildlife. February 1975

Closeup of tall grass, Big Bluestem, covered with winter ice and snow at Lake Quivira, Kansas, near Kansas City. Such vegetation makes excellent cover for wildlife. February 1975

Photos by Patricia D. Duncan (1932-) for the Environmental Protection Agency's DOCUMERICA Project (U.S. National Archives)

Thanks, Tom

ReplyDeleteThanks, Tom: what was isn't, and vice versa. And all popped a memory up from the 1950s of a "sci-fi" book called The Death of Grass by I think a pen-name John Christopher.

ReplyDeleteAnd thanks to you, Tom.

ReplyDeleteAnd what's more, Tom, what isn't (sci-fi), always might be (the new plundered world, inexorably gaining on us).

The conversation about Ed over on Nor[m]a's brilliant Vaquero comic left me suspended between worlds, as it were... That is, between past and I-don't-want-to-know.

Ed was fond of this poem and in fact (those were the days) I understand he actually SANG it (yet!) at the MLA Convention in Houston (this was in 1984 or so), with the renowned country-swing musical-artist-cum-hobo poet Dobro Dick Dillof (who I believe had been living in a railroad car in Montana around that time) providing string accompaniment.

(Memory services always of course just that wee bit doubtful but equally gratis so at least the price of looking back is usually about right.)

in the grass...we are the same...

ReplyDeleteJohn Christopher! I read his Tripods novels when I was an apocalypse-minded preteen. I'll have to read Death of Grass now that I'm an apocalypse minded adult.

ReplyDeleteI'm about to head out on a walk up Mt. Tam. Thanks, Tom C. for giving me a rhythm to walk with.

Great poem.

ReplyDeleteFor a while, I lived in Champaign-Urbana, where some thoughtful souls had preserved a plot of prairie grass against the ravages of ‘progress.’ Prairie grass, I later learned, puts down such a deep and robust root system that when pioneer sodbusters systematically ‘broke the plains,’ their new-and-improved steel plows created a loud popping noise, like gunshots, as they ripped through the earth.

Great pictures.

Many thanks, friends.

ReplyDeleteHazen, you've about summed it up re. the sodbusters.

"...a loud popping noise, like gunshots, as they ripped through the earth."

"Sons of the pioneers," that hackneyed phrase, means the inheritors of the great American tradition: use it up, ruin it for everybody else forever, then move on to the next place that looks ripe for trashing.

It's amazing that Native American peoples managed these lands so well for so long -- the systems of the earth kept intact and thriving and sustained from generation to generation -- through a kind of wisdom so much more impressive (to me anyhow) than that of (say) Google, which now has to sequester entire runways and hangars at one "public" airport (San Jose, to all intents and purposes their company town) merely to provide barn-space for its fleets of corporate jets & c.

But speaking of "public" spaces... dream on, Tom... Google owns the very comment boxes in which we flail and thresh with our ineffectual little words. We're merely worker drones on their cyber labour farms.

And we won't even speak of e.g. Monsanto, here.

It took two generations after Patricia D. Duncan's magnificent photo survey, and a great deal of further trouble as well, before in 2005 ecology lobby groups (led by the Nature Conservancy) managed to secure a tiny fraction (4%) of the remaining tallgrass prairie, in the Flint Hills region of Kansas, as a protected area. In 2009 thirteen bison were shipped in, in hope of rebuilding some semblance of that vast herd of grazing animals which once made the tallgrass ecosystem a self-maintaining proposition. But of course the second temple was never going to be like the first -- so time, like they say, must tell.

ReplyDeleteTallgrass Prairie National Preserve

The rolling hills are still there, and those few token bison, feeding on that patch of nutritious, deep-rooted big bluestem which is all that remains of the virgin prairie... and right alongside those few bison, the thousands of head of cattle which are shipped into Kansas every spring to be fattened up so that a nation of incorrigible consumers of animal flesh may continue the great historical animal sacrifice ritual which incidentally fills the bodies of the citizenry with all that good stuff that keeps the heart attacks and strokes coming, thus in turn ensuring the continuing success of all those vast medical and pharmaceutical industries which make this nation what it is.

__

BTW It clicks in somewhere in the unlit rear chambers of the cranial noodleroni-unit that the Christopher book made it into the movies, in typically mutated form (well, after all, what would the end of life on this planet be without a few good mutations?). Cornel Wilde directed it for MGM, under the title No Blade of Grass. For plant virus, substitute nuclear fallout. (Six of one & c.) Full film as well as previews available on U-Boats. A bit earlier the Christopher book (well, it turns out Christopher's name was actually Sam Youd) was also mined by Hollywood for another film which might even be a hair more subtle (though when the last defense of civilization against the post-apocalyptic punk-swarms is a gun-toting Frankie Avalon, firing at will from the back of the mobile home... it's ducktail v. ducktail, then... pop-pop-pop, take that, daddy-o!... what hope has the race?)

The latter vehicle stars an extremely agitated Ray Milland, at least. It was called Panic in Year Zero.

But digging up the Christopher, one discovers that, in ye original textogram, the virus which kills off the grasses begins as a mutation in Southeast Asian rice crops and then spreads worldwide -- only is no respecter of grass strains, so kills off the wheat and barley as well as the tall grasses. Thus, no more proper food for ye earthlings, ever, sorry about that.

But wait, isn't that happening already?

Post-apocalyptic famine-dodging may soon become a fine art. Our dwarf czar there in the casa blanca may be forced to call in a drone strike, target-of-opportunity naturally. But which general direction of fire shall we choose, sir -- after all, there are at least four "on the table".

Either that or simply stamp the eagle talon of approval upon that new secret legislation providing for genetically modified human embryos, requiring no food at all and resistant to all strains of virus, including life.

IN REVERENCE

ReplyDeleteSo sad the long

Grasses, heads bowed

To the whims of the gods of the stock

Market winds.

Thanks for this posting, Tom. I've always loved your poem "Grasses," and the photos are perfect.

ReplyDeleteThank you friends, for communalizing this small elegy for the tall grasses.

ReplyDeleteReminded of Marvell's Mower to the Glow-Worms:

Ye living lamps, by whose dear light

The nightingale does sit so late,

And studying all the summer night,

Her matchless songs does meditate;

Ye country comets, that portend

No war nor prince’s funeral,

Shining unto no higher end

Than to presage the grass’s fall...