.

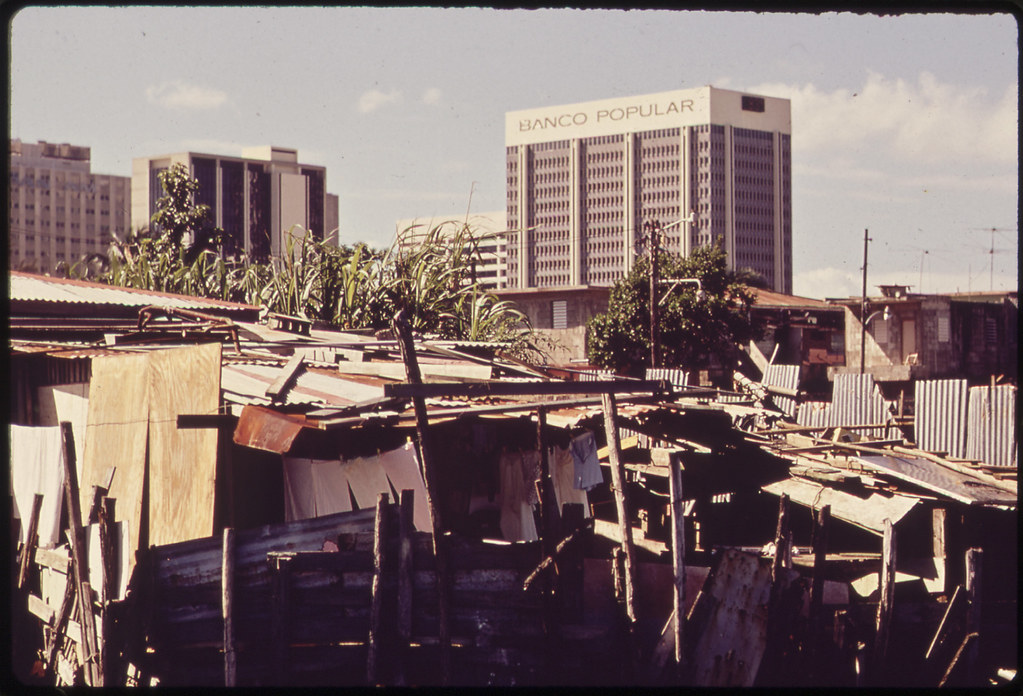

Modern buildings tower over the shanties crowded along the Martín Peña Canal, San Juan: photo by John Vachon for the Environmental Protection Agency's Documerica Project, February 1973 (U.S. National Archives)

For centuries, water from the San José Lagoon emptied

into the ocean by way of the Martin Peña Canal, a shallow, narrow,

three-mile-long channel surrounded by mangrove swamps that runs

through the heart of the city of San Juan.

Until the mid-twentieth century, the area around the canal was unsettled and undeveloped. The Great Depression hit Puerto Rico's agricultural economy especially hard, and Hurricanes San Felipe and San Ciprian, two of the worst in Puerto Rican history, destroyed agricultural production and left hundreds of thousands of people homeless. Migrants fled ravaged rural communities for San Juan, and there, lacking the resources for anything else, they began settling the swampland around the Martin Peña Canal.

Generations of Puerto Ricans have since migrated from the countryside to the city, and the canal area is now home to some 30,000 residents in eight distinct communities spanning hundreds of acres. Residents have made the swampland habitable by sinking dirt, garbage, and debris into the swampland until it became firm enough to support the makeshift homes they built from salvaged wood and corrugated tin. There are no paved roads and few basic utilities. Sewage has flowed directly into the canal or into improvised septic systems. These communities fall well below the poverty line. Many residents are the backbone of San Juan's skilled labor force, and their purchases sustain many of the city's small businesses.

These are, as the Puerto Rican legislature has recognized, "communities of irreplaceable importance for the city."

The canal area is, however, also in a state of environmental crisis that has threatened the whole San Juan Bay Estuary system. The wetlands have become dry land. The canal, once some four hundred feet wide at points, has shrunk so much that it no longer serves as the vital link between the San José Lagoon and San Juan Bay. Instead, water from the Lagoon floods the settlements, dredging up raw sewage and eighty years' worth of detritus, sweeping away the ground beneath the homes, and imperiling residents.

By 2001, the Commonwealth and the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, recognizing the severity of this problem, had committed to a far-reaching project to dredge the canal, restore the flow of water, and clean up decades of environmental pollution. Because the lack of sewage systems has been a major source of pollution, as well as a major health hazard, the government has also committed to rehabilitating and revitalizing the canal and its communities as a central aspect of this project. The government estimates that the project will take at least twenty years to complete.

Excerpt from a legal document filed 28 April 2010, United States Court of Appeals for the First Circuit, Case #09-2569

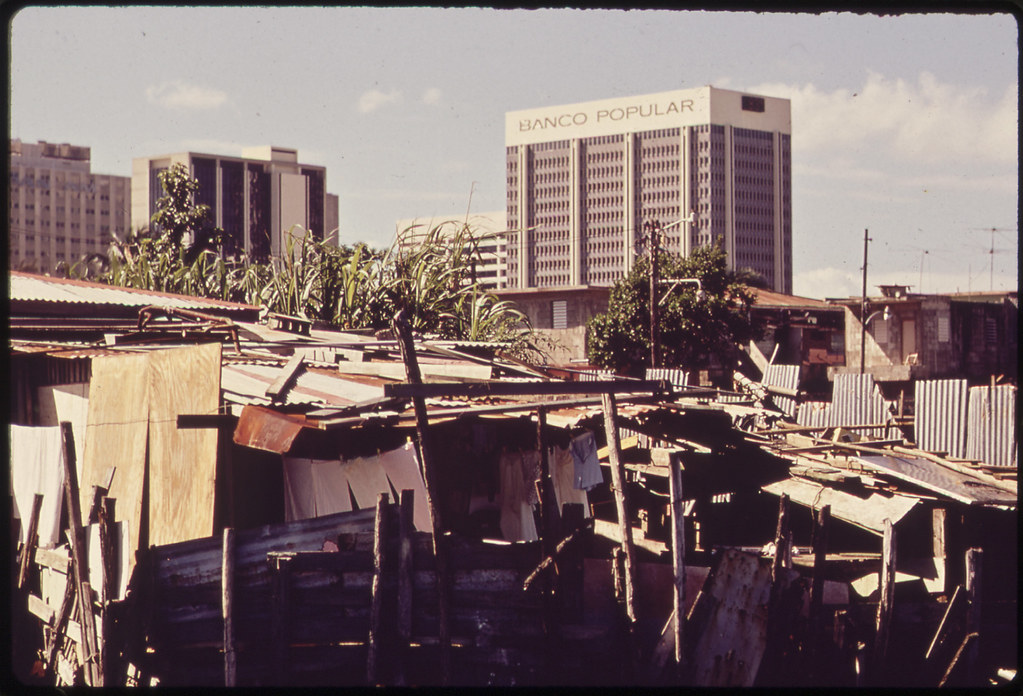

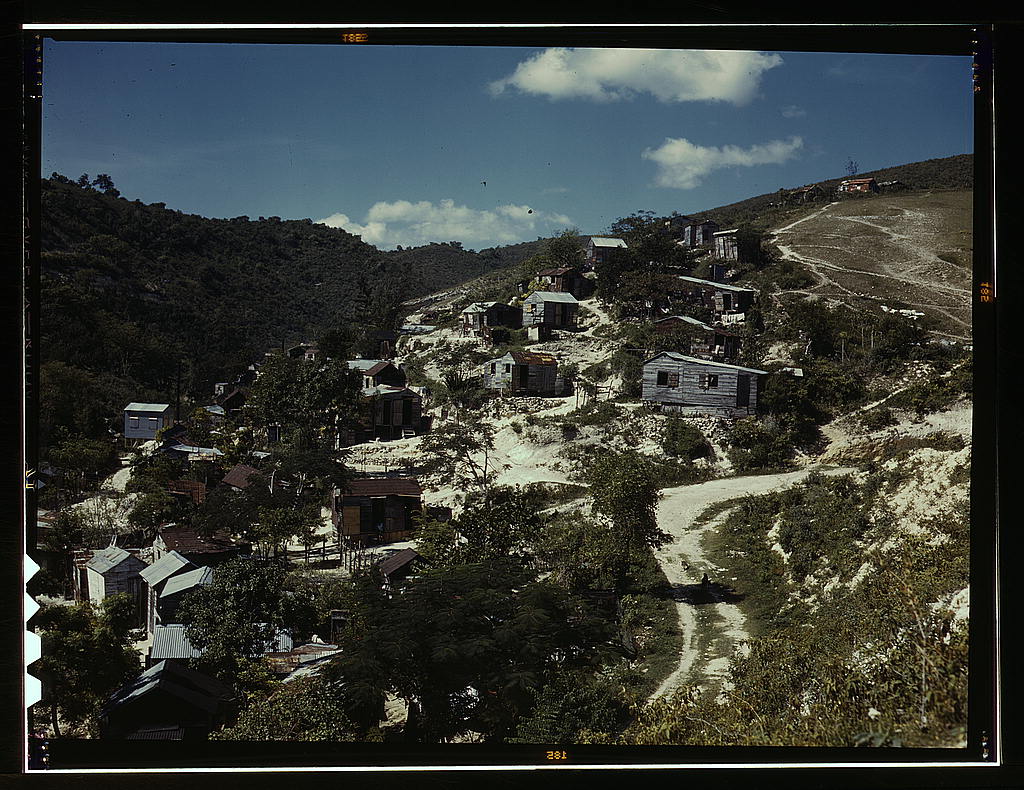

Squatters' Community, San Juan, Puerto Rico: photo by Ken Heyman for the Environmental Protection Agency's Documerica Project, April 1972 (U.S. National Archives)

Modern buildings tower over the shanties crowded along the Martín Peña Canal, San Juan: photo by John Vachon for the Environmental Protection Agency's Documerica Project, February 1973 (U.S. National Archives)

Martín Peña area of Santurce, San Juan, Puerto Rico: photo by Ken Heyman for the Environmental Protection Agency's Documerica Project, April 1972 (U.S. National Archives)

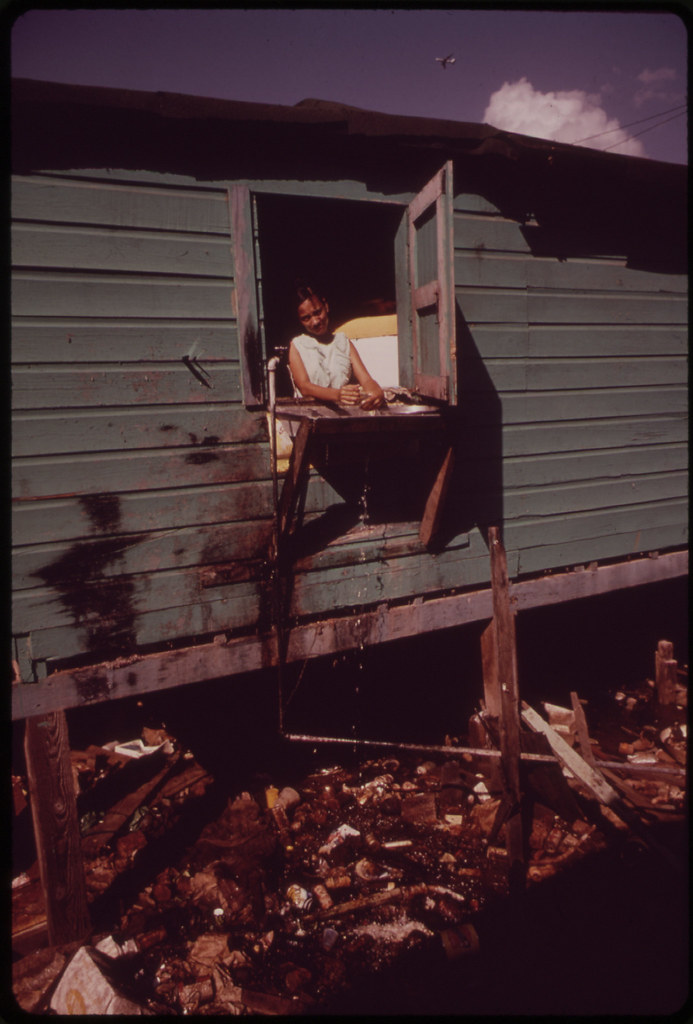

Martín Peña area of Santurce, San Juan, Puerto Rico: photo by Ken Heyman for the Environmental Protection Agency's Documerica Project, April 1972 (U.S. National Archives)

Until the mid-twentieth century, the area around the canal was unsettled and undeveloped. The Great Depression hit Puerto Rico's agricultural economy especially hard, and Hurricanes San Felipe and San Ciprian, two of the worst in Puerto Rican history, destroyed agricultural production and left hundreds of thousands of people homeless. Migrants fled ravaged rural communities for San Juan, and there, lacking the resources for anything else, they began settling the swampland around the Martin Peña Canal.

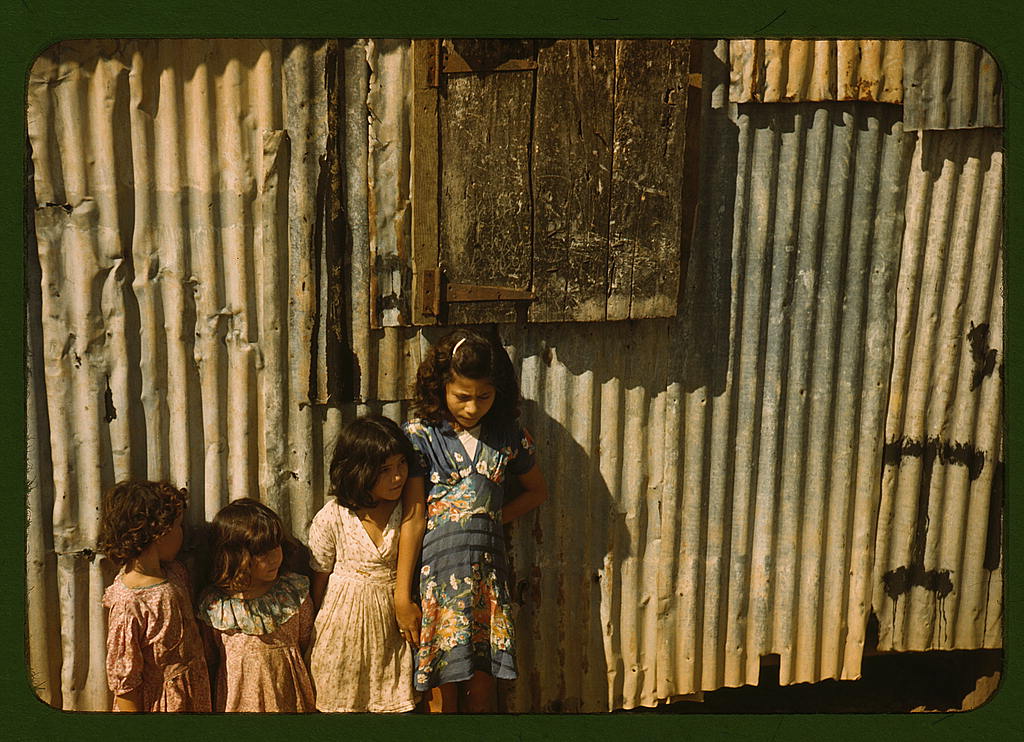

Generations of Puerto Ricans have since migrated from the countryside to the city, and the canal area is now home to some 30,000 residents in eight distinct communities spanning hundreds of acres. Residents have made the swampland habitable by sinking dirt, garbage, and debris into the swampland until it became firm enough to support the makeshift homes they built from salvaged wood and corrugated tin. There are no paved roads and few basic utilities. Sewage has flowed directly into the canal or into improvised septic systems. These communities fall well below the poverty line. Many residents are the backbone of San Juan's skilled labor force, and their purchases sustain many of the city's small businesses.

These are, as the Puerto Rican legislature has recognized, "communities of irreplaceable importance for the city."

The canal area is, however, also in a state of environmental crisis that has threatened the whole San Juan Bay Estuary system. The wetlands have become dry land. The canal, once some four hundred feet wide at points, has shrunk so much that it no longer serves as the vital link between the San José Lagoon and San Juan Bay. Instead, water from the Lagoon floods the settlements, dredging up raw sewage and eighty years' worth of detritus, sweeping away the ground beneath the homes, and imperiling residents.

By 2001, the Commonwealth and the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, recognizing the severity of this problem, had committed to a far-reaching project to dredge the canal, restore the flow of water, and clean up decades of environmental pollution. Because the lack of sewage systems has been a major source of pollution, as well as a major health hazard, the government has also committed to rehabilitating and revitalizing the canal and its communities as a central aspect of this project. The government estimates that the project will take at least twenty years to complete.

Excerpt from a legal document filed 28 April 2010, United States Court of Appeals for the First Circuit, Case #09-2569

Squatters' Community, San Juan, Puerto Rico: photo by Ken Heyman for the Environmental Protection Agency's Documerica Project, April 1972 (U.S. National Archives)

Modern buildings tower over the shanties crowded along the Martín Peña Canal, San Juan: photo by John Vachon for the Environmental Protection Agency's Documerica Project, February 1973 (U.S. National Archives)

Martín Peña area of Santurce, San Juan, Puerto Rico: photo by Ken Heyman for the Environmental Protection Agency's Documerica Project, April 1972 (U.S. National Archives)

Martín Peña area of Santurce, San Juan, Puerto Rico: photo by Ken Heyman for the Environmental Protection Agency's Documerica Project, April 1972 (U.S. National Archives)

Martín Peña area of Santurce, San Juan, Puerto Rico: photo by Ken Heyman for the Environmental Protection Agency's Documerica Project, April 1972 (U.S. National Archives)

Martín Peña area of Santurce, San Juan, Puerto Rico: photo by Ken Heyman for the Environmental Protection Agency's Documerica Project, April 1972 (U.S. National Archives)

Martín Peña area of Santurce, San Juan, Puerto Rico: photo by Ken Heyman for the Environmental Protection Agency's Documerica Project, April 1972 (U.S. National Archives)

Martín Peña area of Santurce, San Juan, Puerto Rico: photo by Ken Heyman for the Environmental Protection Agency's Documerica Project, April 1972 (U.S. National Archives)

Martín Peña area of Santurce, San Juan, Puerto Rico: photo by Ken Heyman for the Environmental Protection Agency's Documerica Project, April 1972 (U.S. National Archives)

El Fanguito, San Juan: photo by Melvin Lauver, c. 1946-48; image by Tom Lehman, 20 July 2011

(El Fanguito translates to Little Mud. It was the largest slum in San Juan, extending from next to Miramar Naval Station, along both sides of the Martin Peña Canal all the way to the bridge in Hato Rey. The residents were moved to Caserío San José in Rio Piedras and the shacks were torn down.-- Tito Stevens)

Man carrying wicker furniture for sale, San Juan: photo by Melvin Lauver, c. 1946-48; image by Tom Lehman, 19 July 2011

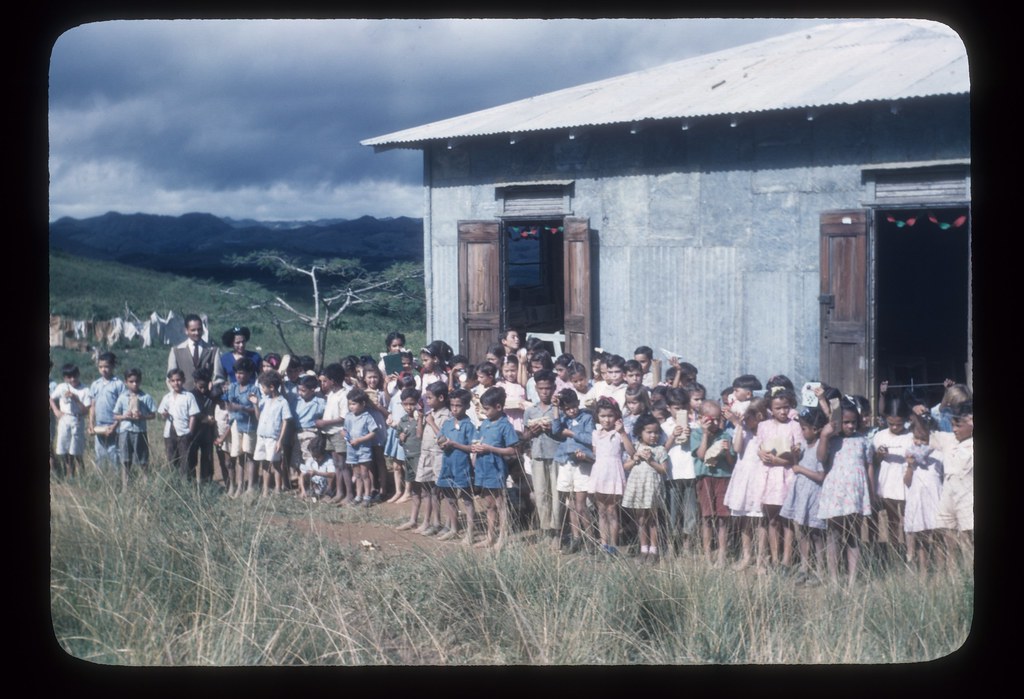

Children in front of school, Puerto Rico: photo by Melvin Lauver, c. 1946-48; image by Tom Lehman, 20 July 2011

Three children and chickens by house close to tobacco field, Puerto Rico: photo by Melvin Lauver, c. 1946-48; image by Tom Lehman, 18 July 2011

Alcoholado Mejor sign, Ponce: photo by Melvin Lauver, c. 1946-48; image by Tom Lehman, 10 July 2011

Baseball game, Sixto Escobar Stadium, San Juan: photo by Melvin Lauver, c. 1946-48; image by Tom Lehman, 10 July 2011

Fort San Felipe del Morro, San Juan, Puerto Rico: photo by Robert Yarnall Richie, 1939 (Southern Methodist University Central Libraries / DeGolyer Library)

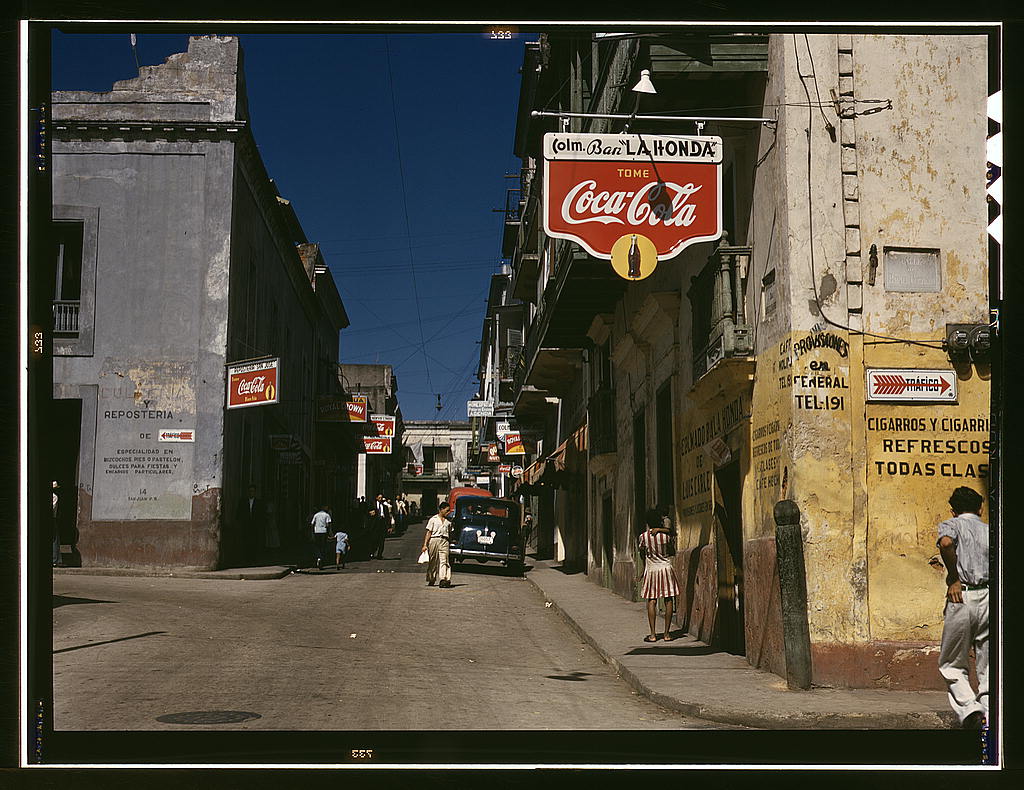

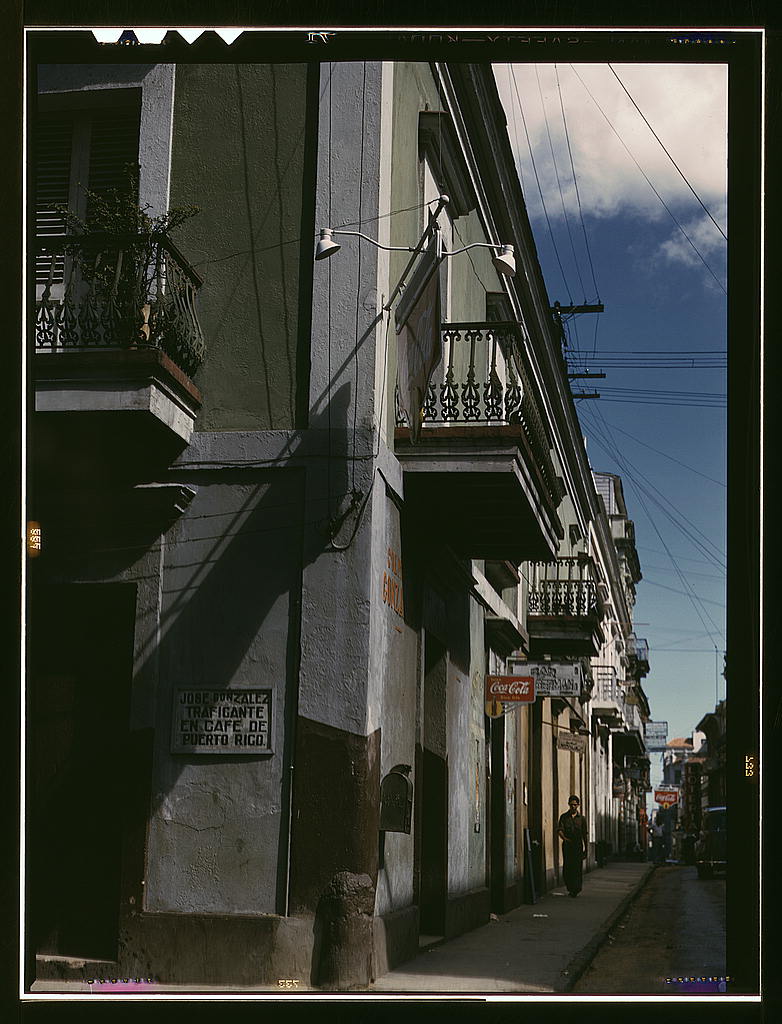

Street in San Juan: photo by Jack Delano, December 1941 (Farm Security Administration/Office of War Information Collection, Library of Congress)

Street in San Juan: photo by Jack Delano, December 1941 (Farm Security Administration/Office of War Information Collection, Library of Congress)

Children in a company housing settlement, Puerto Rico: photo by Jack Delano, December 1941 (Farm Security Administration/Office of War Information Collection, Library of Congress)

FSA -- T[enant] P[urchase] borrowers? by their house, Puerto Rico: photo by Jack Delano, December 1941 or January 1942 (Farm Security Administration/Office of War Information Collection, Library of Congress)

FSA -- T[enant] P[urchase] borrower? by his field, Puerto Rico: photo by Jack Delano, December 1941 or January 1942 (Farm Security Administration/Office of War Information Collection, Library of Congress)

Child of an FSA -- R.R. borrower? in front of house, Puerto Rico: photo by Jack Delano, December 1941 or January 1942 (Farm Security Administration/Office of War Information Collection, Library of Congress)

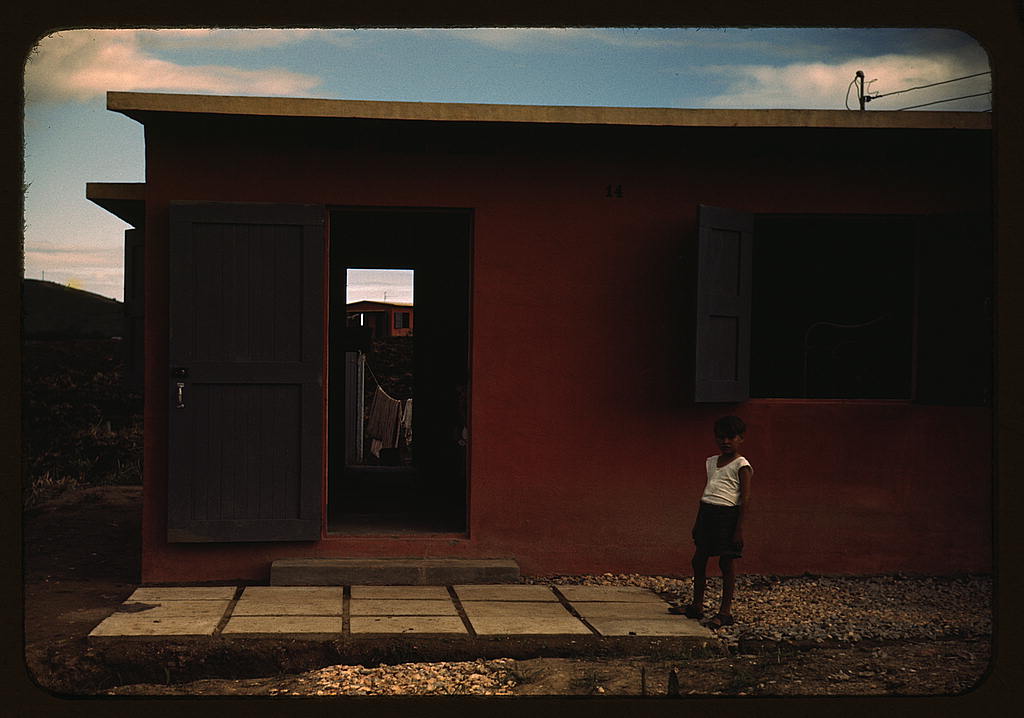

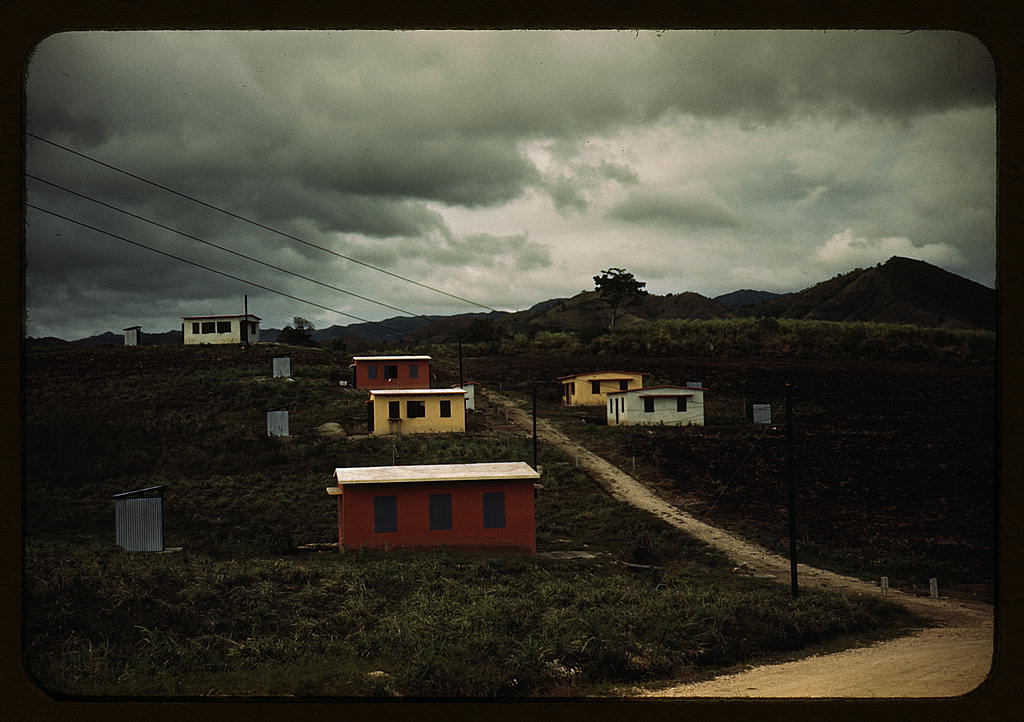

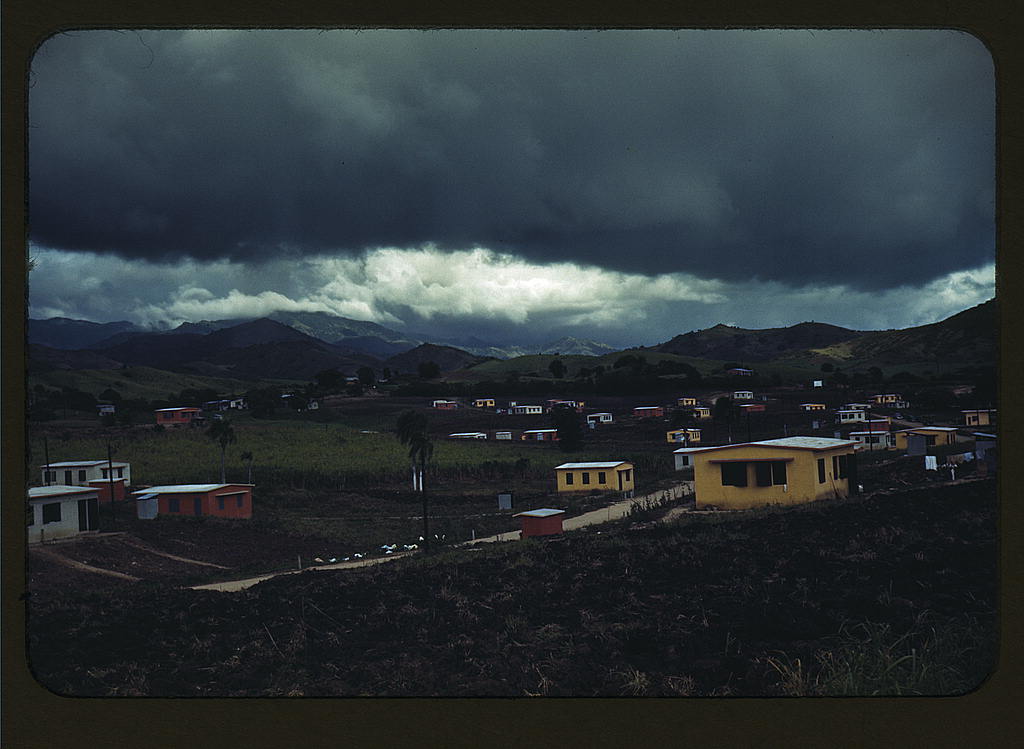

Federal housing project on the outskirts of the town of Yauco, Puerto Rico: photo by Jack Delano, January 1942 (Farm Security Administration/Office of War Information Collection, Library of Congress)

Federal housing project on the outskirts of the town of Yauco, Puerto Rico: photo by Jack Delano, January 1942 (Farm Security Administration/Office of War Information Collection, Library of Congress)

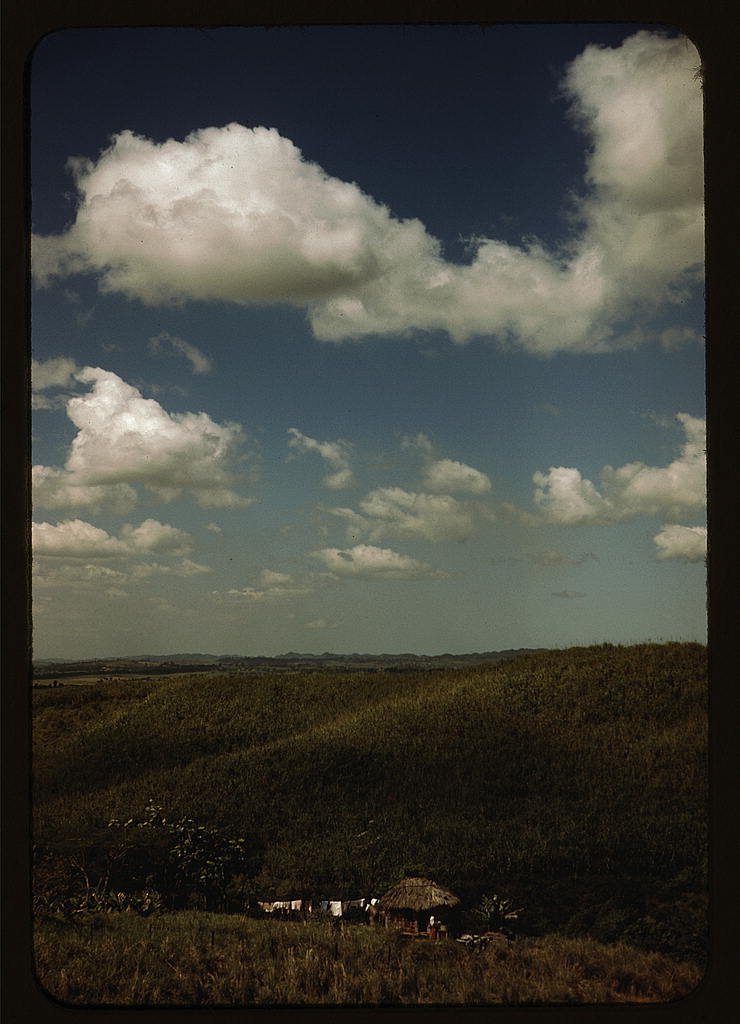

Sugar cane land, vicinity of Rio Piedras, Puerto Rico: photo by Jack Delano, December 1941 (Farm Security Administration/Office of War Information Collection, Library of Congress)

Sugar cane land, vicinity of Rio Piedras, Puerto Rico: photo by Jack Delano, December 1941 (Farm Security Administration/Office of War Information Collection, Library of Congress)

Sugar cane worker and his woman, Rio Piedras, Puerto Rico: photo by Jack Delano, December 1941 (Farm Security Administration/Office of War Information Collection, Library of Congress)

Sugar cane workers resting, Rio Piedras, Puerto Rico: photo by Jack Delano, December 1941 (Farm Security Administration/Office of War Information Collection, Library of Congress)

A town in Puerto Rico: photo by Jack Delano, December 1941 (Farm Security Administration/Office of War Information Collection, Library of Congress)

A town in Puerto Rico: photo by Jack Delano, December 1941 (Farm Security Administration/Office of War Information Collection, Library of Congress)

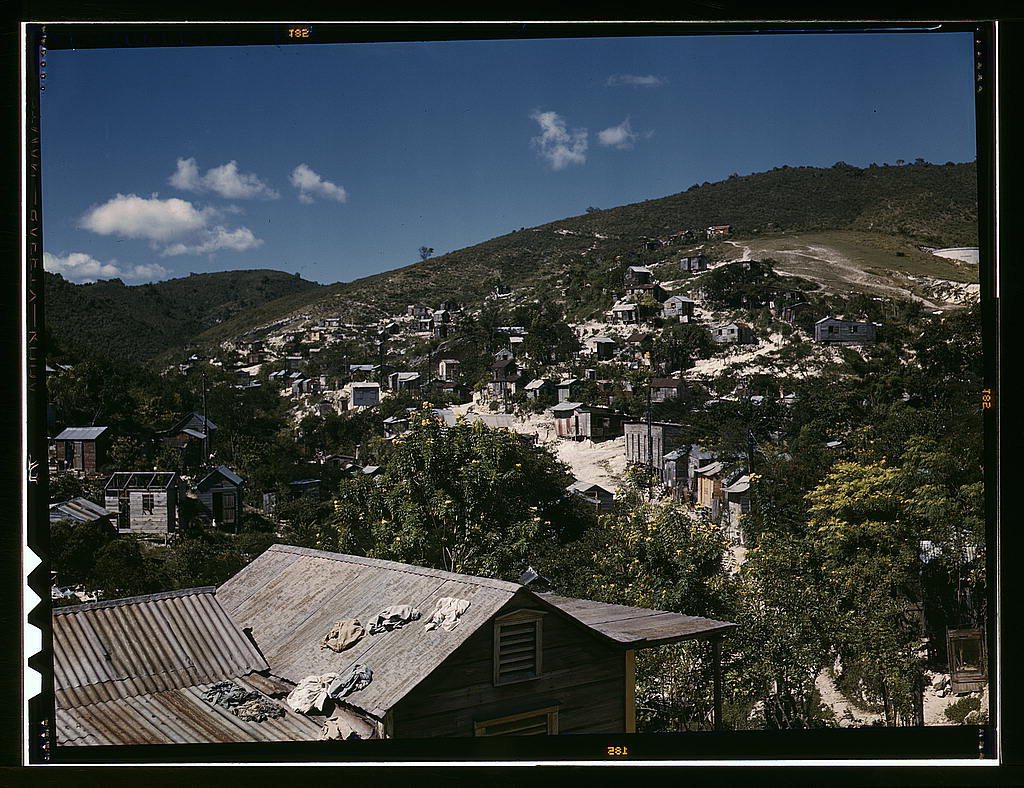

Small farms in the hills, vicinity of Corozal, Puerto Rico: photo by Jack Delano, December 1941 (Farm Security Administration/Office of War Information Collection, Library of Congress)

Malaria poster, Puerto Rico: photo by Jack Delano, December 1941 (Farm Security Administration/Office of War Information Collection, Library of Congress)

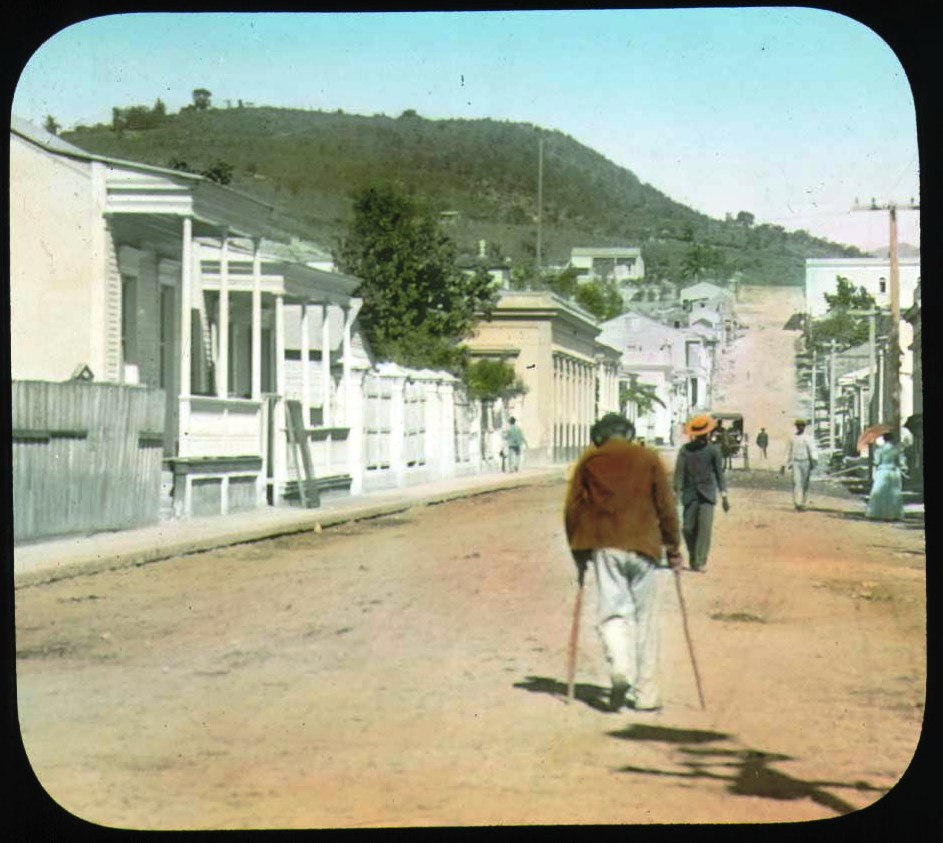

Street with people, San Juan, Puerto Rico: hand colored lantern slide from Alison V. Armour Expedition, 1898-99 [In 1898, during the Spanish–American war, Puerto Rico was invaded and subsequently became a possession of the United States]; image by The Field Museum Library, 8 March 2007

Street with people, man on crutches, Ponce, Puerto Rico: hand colored lantern slide from Alison V. Armour Expedition, 1898-99; image by The Field Museum Library, 8 March 2007

Marketplace in Ponce, Puerto Rico: hand colored lantern slide from Alison V. Armour Expedition, 1898-99 [In 1898, during the Spanish–American war, Puerto Rico was invaded by and subsequently became a possession of the United States]; image by The Field Museum Library, 8 March 2007

Settlements on the margins of the Caño Martín Peña, San Juan: photo by Moebiusuibeom-en, 9 November 2012

"In the beginning of the twentieth century, during a time of hardship and extreme poverty, many Puerto Ricans migrated to the larger coastal cities on the Island in search of employment and a better life. In the process of laying a solid foundation for their homes and families, these people gave rise to a number of close-knit communities; they established the precedent so that others in similar situations would have at the very least a glimmer of hope for a brighter future for themselves and their families." — extract from The Caño Martín Peña Community Land Trust is Struggling to Survive, by María E. Hernández-Torrales, member of the Board of Trustees of the Fideicomiso de la Tierra del Caño Martín Peña. Barrio Obrero, Santurce: photo by Moebiusuibeom-en, 9 November 2012

Valley with hills and river, Puerto Rico: photo by Melvin Lauver, c. 1946-48; image by Tom Lehman, 18 July 2011

Lush valley, Puerto Rico: photo by Melvin Lauver, c. 1946-48; image by Tom Lehman, 10 July 2011

Sailboats in San Juan Bay: photo by Melvin Lauver, c. 1946-48; image by Tom Lehman, 20 July 2011

Shoreline, Puerto Rico: photo by Robert Yarnall Richie, 1939 (Southern Methodist University Central Libraries / DeGolyer Library)

Map of Porto Rico [Puerto Rico]: from Porto Rico: the Land of the Rich Port by Joseph Bartlett Seabury, 1903 (Stanford University Library)

Testing [captured] Spanish guns, San Cristobal, Puerto Rico: hand colored lantern slide from Alison V. Armour Expedition, 1898-99 ; image by The Field Museum Library, 8 March 2007

Boat in harbor flying U.S. flag, Puerto Rico: hand colored lantern slide from Alison V. Armour Expedition, 1898-99; image by The Field Museum Library, 8 March 2007

Portrait of Christopher Columbus, explorer credited with the "discovery" of Puerto Rico: Sebastian del Piombo, c. 1520, oil on canvas; image by Jarekt, 4 August 2009

Portrait of Christopher Columbus: Cristofano dell'Altissimo, 1556, oil on canvas, 59 x 42 cm (Galleria degli Uffizi, Florence)

Gold is a most excellent thing. It constitutes treasure. Whoever has it can do what he likes in the world and even manage to get souls into Paradise.

-- Cristóbal Colón (aka Christopher Columbus), merchant navigator of Genoa, dictated dispatch from the Indies to The Most Serene, High and Potent Princes, the King and Queen, Ferdinand and Isabella of Spain, 7 July 1503

Glory of Spain (detail): Giovanni Battista Tiepolo, 1762-66, fresco, 2700 x 1000 cm (Throne Room, Palacio Real, Madrid)

Tom,

ReplyDelete"Gold is a most excellent thing. It constitutes treasure. Whoever has it can do what he likes in the world and even manage to get souls into Paradise."

And here we are, and the rains are back --

2.19

grey white rain cloud against invisible

top of ridge, sparrow calling on branch

in foreground, wave sounding in channel

from center to point at far

right, color position

across the picture, pyramid

beyond which, picture

grey white clouds reflected in channel,

shadowed green pine on tip of sandspit

So familiar, these photos. I lived a year in the teak forests above Arecibo, and stood on those ramparts at El Morro. I ate my first-ever paella in Old San Juan, and trekked the interior of the island, where the mountains are like haystacks and bilharzia lurked in the streams.

ReplyDeleteBeautiful Puerto Rico. It fell into our clutches after another ginned up war, this time with a moribund European empire. Maybe we didn’t invent the false flag gambit, but we’ve perfected it. We went up against Spain “to free the Cubans from the tyranny” (sounds familiar) and grabbed Puerto Rico and the Philippines and a bit more real estate to boot. The Dollar Follows the Flag became the slogan of the day. Your photos illustrate what else followed in the wake of our imperial ambitions.

Today Columbus, the greedy old bugger, would be what they call an entrepreneur, when in reality he was vicious sociopath.

Wonderful photos. Incidentally, that photo of Santiago is most likely at Santiago de Cuba.

Steve,

ReplyDeleteSlopping down in buckets over here this morning, too, just

across the picture.

Hazen,

The Genovese mercenary gives it all away with that steely glance.

And...

"With a little help from one's friends" always has room for a bit of new meaning.

Of course you are right, and the archivist of the Field Museum, dead wrong, about the Cristóbal Colón.

I had a a funny feeling about that caption. After all, the same ship cannot be sunk in two harbors at once -- even by the US Navy.

The picture has now been buried at sea.

And I have had the opportunity to refresh my knowledge font

regarding the Battle of Santiago de Cuba, 3 July 1898 -- the decisive naval engagement of the Spanish-American War.

The picture didn't belong, but in a larger sense (?), Old Empire v. New, perhaps the story fits here anyhow.

As follows:

"Within a little more than an hour, five of the six ships of the Spanish Caribbean Squadron had been destroyed or forced aground. Only one vessel, the speedy new armored cruiser Cristóbal Colón, still survived, steaming as fast as she could for the west and freedom. Though modern in every respect and possibly the fastest ship in either fleet, Cristóbal Colón had one serious problem: She had been only recently purchased from Italy, and her main 10 in (250 mm) armament was not yet installed because of a contractual issue with the British firm of Armstrong. She therefore sailed with empty main turrets, albeit retaining her ten 6 in (150 mm) secondary battery. This day, speed was her primary defense.

"At her best rate of nearly 20 kn (23 mph; 37 km/h), Cristóbal Colón slowly distanced herself from the pursuing U.S. fleet. Her closest antagonist, USS Brooklyn, had begun the battle with just two of her four engines coupled, because of her long stay on the blockade line, and could manage barely 16 kn (18 mph; 30 km/h) while building steam. As Brooklyn ineffectively fired 8 in (200 mm) rounds at the rapidly disappearing Cristóbal Colón, there was only one ship in the U.S. fleet with a chance of maintaining the pursuit, the Oregon. For 65 minutes, Oregon pursued Cristóbal Colón. Cristóbal Colón had to hug the coast and was unable to turn toward the open sea because Oregon was standing out about 1.5 mi (1.3 nmi; 2.4 km) from Cristóbal Colón's course and would have been able to fatally close the gap had Cristóbal Colón turned to a more southerly course.

"Finally, three factors converged to end the chase: First, Cristóbal Colón had run through her supply of high-quality Cardiff coal and was forced to begin using an inferior grade obtained from Spanish reserves in Cuba. Second, a peninsula jutting out from the coastline would soon force her to turn south, across Oregon's path. And third, on the flagship Brooklyn, Commodore Schley signaled Oregon's Captain Charles Clark to open fire. Despite the immense range still separating Oregon and Cristóbal Colón, Oregon's forward turret launched a pair of 13 in (330 mm) shells which bracketed Cristóbal Colón's wake just astern of the ship.

"Captain Emilio Diaz Mopreu, declining to see his crew killed to no purpose, abruptly turned the undamaged Cristóbal Colón toward the mouth of the Tarquino River and ordered the scuttle valves opened and the colors struck as she grounded. His descending flag marked the end of Spain's naval power in the New World."

Tom, Good read. In the case of the Cristóbal Colón, it seems that "contractual issues"—not loose lips—sink ships. Ah, the exigencies, and the fine print, of empire.

ReplyDeleteTake heart, my children—no matter how dirt poor backwards and enslaved you can be, there will always be a Coca-Cola sign leading you forward to the land of the free.

ReplyDeleteWell, of course one can never trust a contractor.

ReplyDeleteI believe I counted five Coca-Cola and three Royal Crown signs in that one narrow San Juan side street.

But then what would Paradise be without the sugar?

I want to thank you for making this blog and posting this priceless documentary. My father is a survive of this filthy place.

ReplyDeleteHe tells of the many times he and his five brothers roamed the filthy street looking for food and a place to lay their heads.

He vowed that he would never allow his children to live this way. With his hard work and perseverance, he gave us the best money could buy including a private school education.

Because of him, we are all very successful in life.

Today, he lives in Central Florida, retired, and lives with his soul mate for the past 55 years.

Thank you for sharing this priceless documentary with the world. God bless you!