.

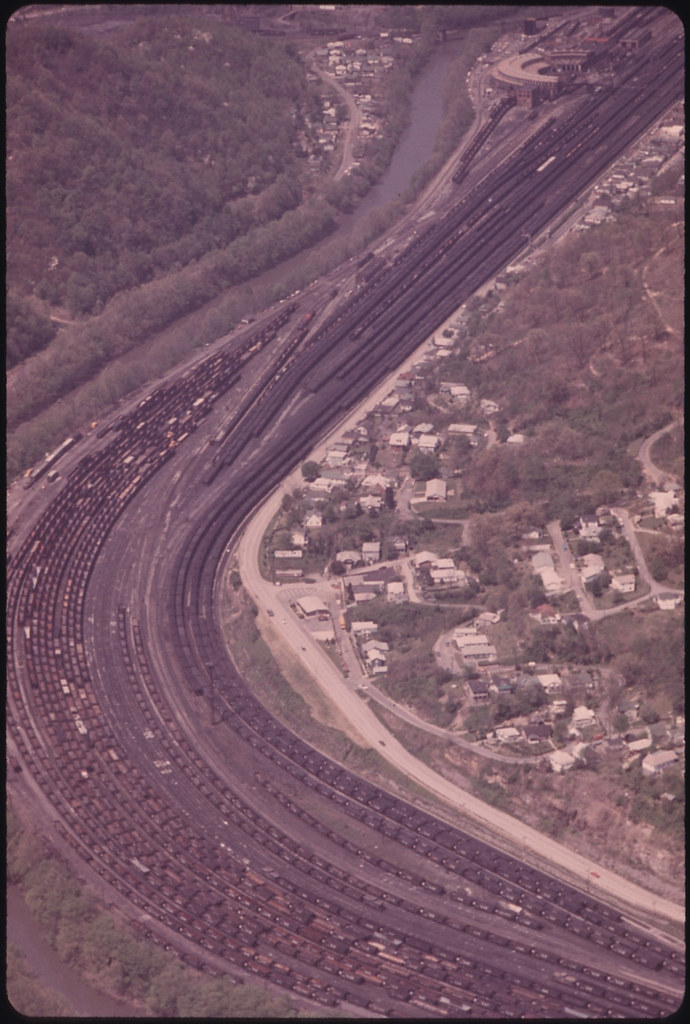

Loaded coal cars sit in the rail yards at Danville, West Virginia, near Charleston, awaiting shipment to customers. It is one of the largest transshipment points for coal in the world. A constant stream of rail cars is moved in and out of the small town, April 1974

What was it like for you, down there

becoming another statistical indicator

carved on the long wall of the subterranean

psychogeography

......................that severe account book

smudged ledger

where the numbers were never going to

add up for you Those production figures

were never meant

to account for the human price

at which the company store

computes your life

as a fraction of the overall

profit margin

.................haul

sixteen tons what do you

get

another day older

and that much closer to the depth

accumulation the pulmonary

soot burden

dead reckoning

from which there's no rescue

A portion of the rail yards at Danville, West Virginia, near Charleston, loaded with coal cars ready to be hauled to customers in various parts of the country. It is one of the largest transshipment points for coal in the world. A constant stream of coal cars Is moved in and out of the small town, April 1974

Closeup of the old coal company mining town of Red Ash, Virginia, near Richlands in the southwestern part of the state. This Is a classic picture of a company town with a railroad in the valley flanked by miners' homes. These houses are two-family dwellings. The road Is made of red dog [aka coal slag], a mining byproduct, April 1974

Old coal company town of Red Ash, Virginia, near Richlands in Tazewell

County in the southwestern part of the state. This Is a classic picture of a company town with a railroad in the valley flanked by miners' homes. The coal mine superintendent's home Is up the hill in

the upper left portion of the picture. The separation Is symbolic of

the caste system which has ruled in the mining towns. The road Is made of red dog [aka coal slag], a mining byproduct, April 1974

Miner homes in a company town near Cabin Creek and Charleston, West Virginia. The one story structures have four rooms compared to those housing the mine superintendents which were two story with four rooms on each floor. The superintendent homes were apart from the miners, usually on the hill above -- a residual symbol of the caste system which prevailed in earlier mining days, June 1974

Coal City Club in Coal City, West Virginia, a part of Beckley. All of the men are coal miners. Note that some of them are "hunkering down" rather than sitting. This Is a familiar stance to all miners who use this posture in the mine shafts which have low ceilings, June 1974

David Shanklin, 19, lives in a coal company town near Sunbright, West Virginia, and graduated from Logan County High School. His girlfriend, Janet Edwards, 17, still attends high school in Logan. David's father was killed in the mines in 1954 by a roof fall and he wants to be a miner, but his mother doesn't want him to. The youth has a brother working in the mines. Notice the outhouses in front of the homes, April 1974

One of the daughters of Jerry Rainey, 34, a miner who was out on strike against the Brookside Mining Company in Brookside, Kentucky, near Middlesboro, for several months during 1974. She Is on the back porch of the house Rainey rents from the company. Notice the outhouses in the background. The family was threatened by eviction during the lengthy and sometimes violent strike despite a state law which outlaws such a practice, July 1974

Nannie Rainey, 34, wife of miner Jerry Rainey, who lives in housing owned by the Brookside Mine Company near Middlesboro, Kentucky. The company Is owned by the Duke Power Company. She was arrested during the strike in 1974 during an altercation on the picket line in which she was accused of whipping a Kentucky State Highway Patrolman with a switch, a charge she does not deny. She and her children went to jail until bailed out by union officials, June 1974

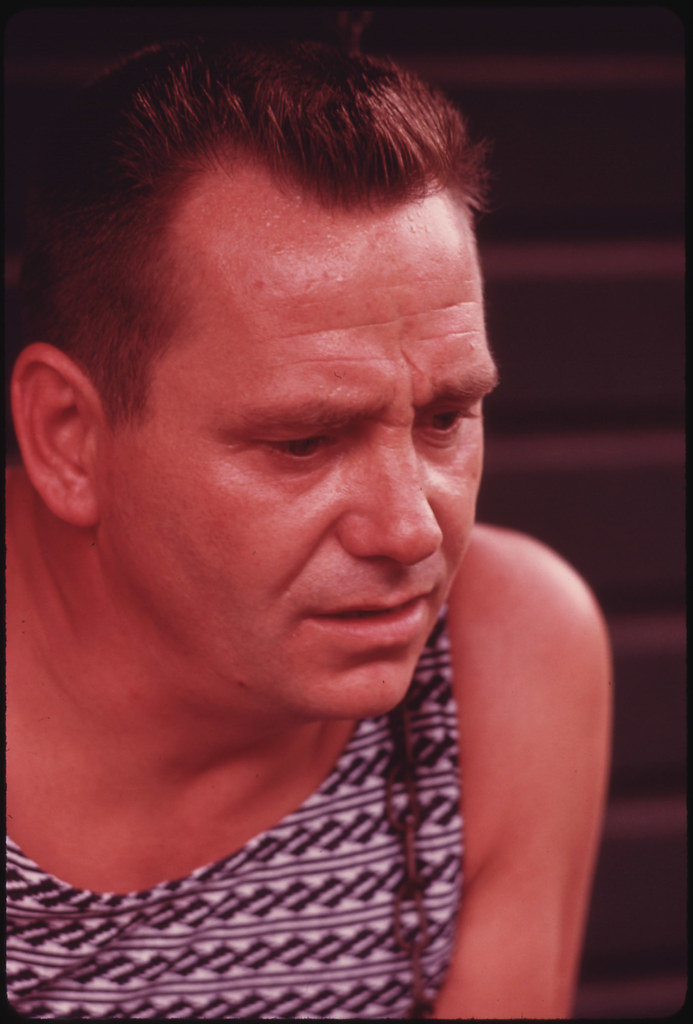

Closeup of Jerry Rainey, 34, miner at the Brookside Mine Company who was out on strike in the summer of 1974. The family had just received an eviction notice from the company house they rented, in violation of a Kentucky state law which prohibits such action during a strike. It was a bitter strike between the Duke Power Company that owned the mine and the United Mine Workers. The strike was violent and lasted several months. It ended when a man was shot and killed on the picket line near Middlesboro, Kentucky, June 1974

Row of miners' homes in the Brookside Mine Company town of Brookside, Kentucky, near Middlesboro. The mine, owned by the Duke Power Company, was the scene of a protracted and sometimes violent strike between the mine company and the United Mine Workers Union during 1974. The strike ended when a man was shot and killed on the picket line in Harlan County. The home of the Jerry Rainey family is in the foreground. They were threatened with eviction during the strike, June 1974

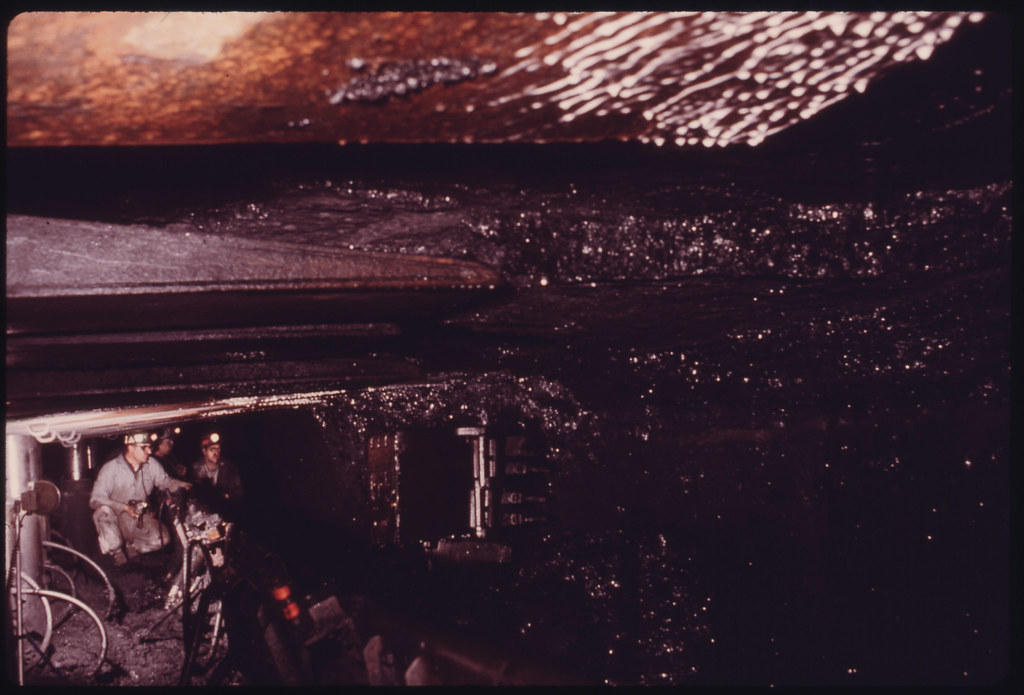

Miner bathed in the glow of a co-worker's lamp Is shown with a shuttle car used for transporting safety men or other small groups. The shuttles used for the miners going to and from work are larger. This Is the Virginia-Pocahontas Coal Company Mine #3 near Richlands, Virginia, April 1974

Miner in Virginia-Pocahontas Coal Company Mine #3 near Richlands, Virginia, operates a shuttle car which takes the coal from the Continuous Miner and moves It out of the tunnel to a conveyor for transport out of the mine. This mine processes metallurgical coal for use in steelmaking furnaces. The shuttle car driver will turn and face the other way on the trip back, April 1974

General scene underground in the Virginia-Pocahontas Coal Company Mine #3 near Richlands, Virginia. The tunnel Is 1,250 feet below the surface and one and a half miles from the elevator shaft which brings the miners to and from work. This is a typical mine scene from a miner's viewpoint, April 1974

Picture of the Long Wall miner with jacks holding up the ceiling to the left and the teeth of the miner on the right. The teeth rake the coal to the conveyor belt below. A continuous spray of water is used on the coal to cut down on the amount of airborne particles (not shown in picture). The face of the Long Wall of coal Is 450 feet. A typical shift Includes 10 men -- a foreman, 2 machine operators, utility man, 5 to 6 jack setters and sometimes a repairman, April 1974

Harley Owens in position as a machine operator on the end of the Long Wall where the coal Is placed on a conveyor belt. A tail operator works on the other end of the machine 450 feet away. This Is Mine #3 of the Virginia-Pocahontas Coal Company near Richlands, Virginia. Long Wall mining is relatively new and more costly, but allows about twice as much coal to be taken from a mine, April 1974

The elevator to the main shaft for men and equipment at the Virginia-Pocahontas Coal Company Mine #4 near Richlands, Virginia. The green building on the right contains an office, shower rooms and warehouses. The small yellow cars behind the elevator fit Into the elevator and are used in the mine. A switch engine, used for outside work, Is seen between the elevator and the building. Coal cars are shown on railroad tracks in the foreground, April 1974

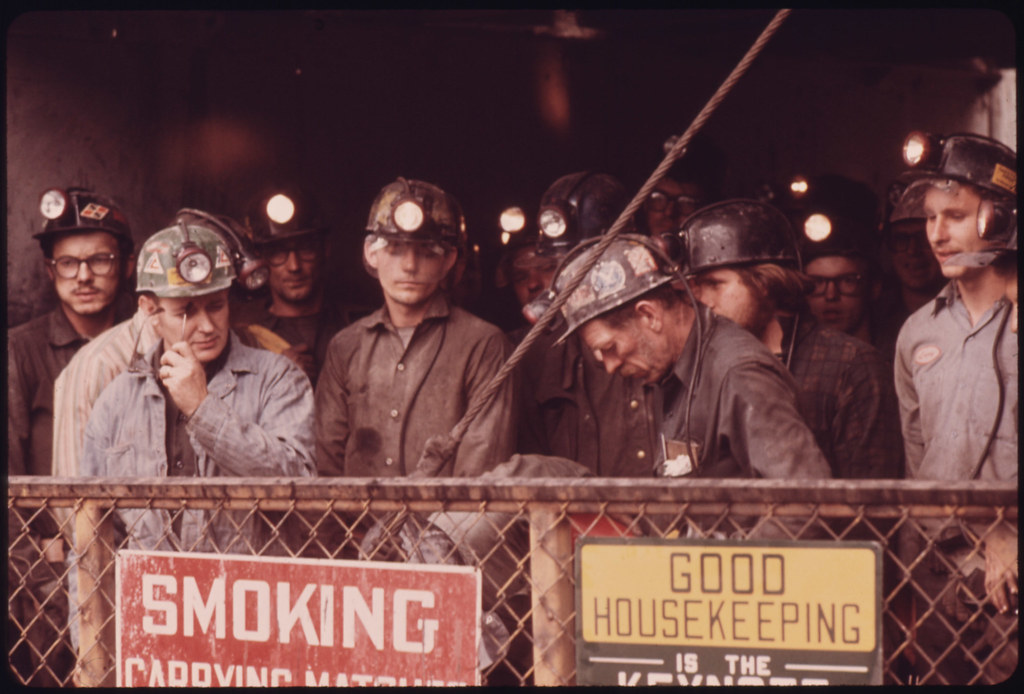

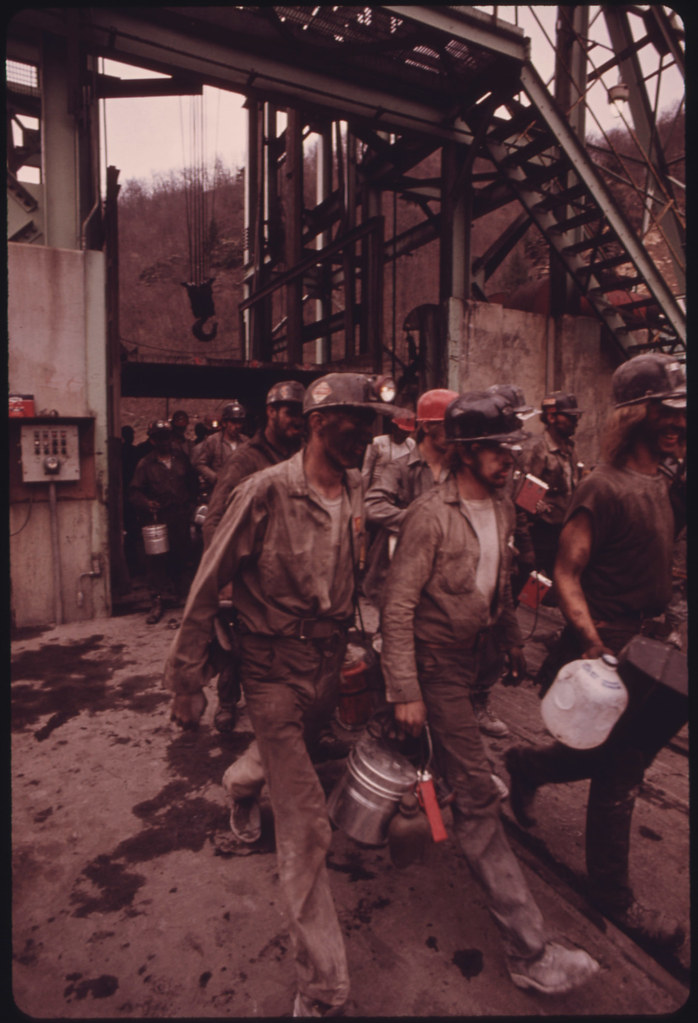

Miners llne up to go into the elevator shaft at the Virginia-Pocahontas Coal Company Mine #4 near Richlands, Virginia. The man at the right wears a red hat which means he Is a new miner and has worked below less than a month. His belt also shows less wear than the others. The miner at the left carries Red Man Chewing Tobacco, used by many of the men because they cannot smoke in the mines. They also prefer to carry their own water rather than use what the company provides, April 1974

Shift of miners in the elevator which will take them down to work in the Virginia-Pocahontas Mine #4 near Richlands, Virginia. They are headed for the 1,200 Foot Level. The black hats signify that the men are experienced miners. The miner with the green Hat Is a safety man. These mines have three shifts, two working and one cleanup, April 1974

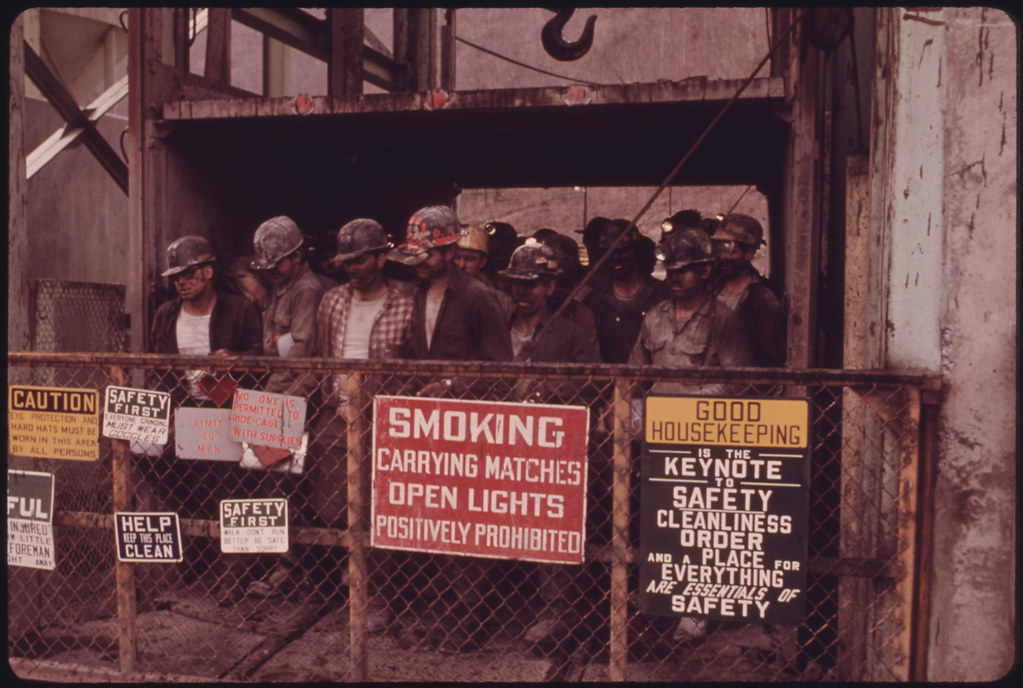

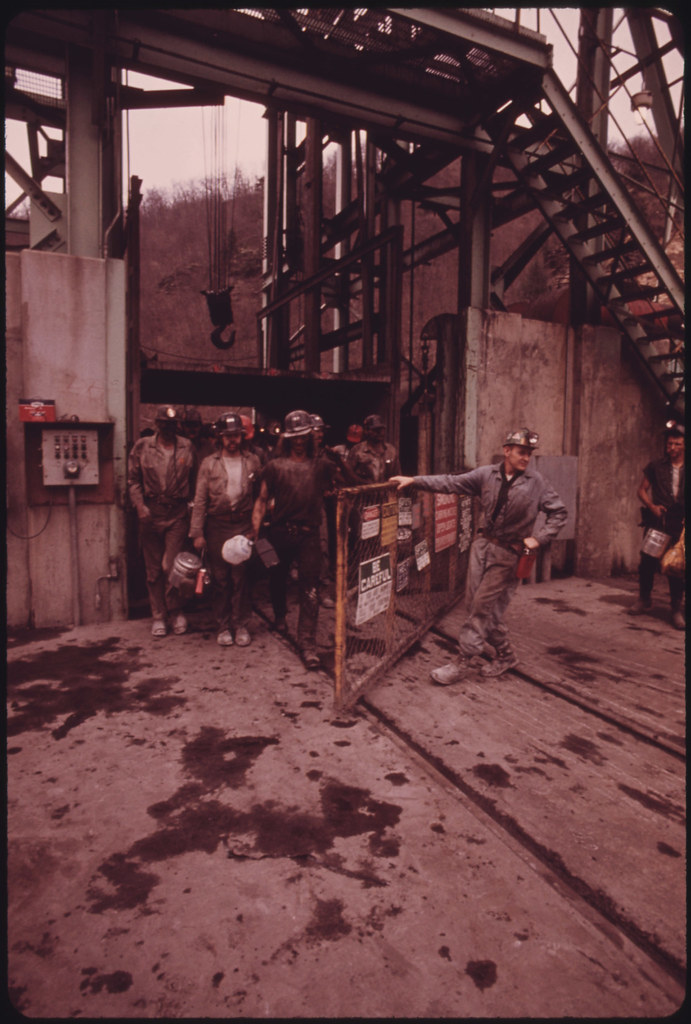

Miners just surfacing on the mine elevator at the Virginia-Pocahontas Mine #4 near Richlands, Virginia. They will make way for the 4 P.M. to midnight shift. The mines have two work shifts and a midnight to morning or "Hoot-Owl" shift for cleanup operations. Note the variety of safety signs on the elevator gate and the prohibition of carrying matches, cigarettes or an open light into the mines. Most of the men who smoke chew tobacco while on the job, April 1974

Miners just emerging from the elevator of Virginia-Pocahontas Coal Company Mine #4 near Richlands, Virginia after returning to the surface from work below. They will be replaced by miners on the 4 P.M. to midnight shift. Both of these shifts are concerned with digging and getting the coal out of the mine. A midnight to morning or "Hoot-Owl" shift Is Involved in daily cleanup operations, April 1974

Miners who have just returned to the surface of Virginia-Pocahontas Coal Company Mine #4 near Richlands, Virginia and will be replaced by men on the 4 P.M. to midnight shift. Many of the miners carry their own water Into work rather than use that provided by the company. They also use chewing tobacco while in the mines because they are not allowed to smoke underground, April 1974

Miners just leaving the elevator shaft of Virginia-Pocahontas Coal Company Mine #4 near Richlands, Virginia at 4 P.M. There are three mine shifts. The first two are employed in digging and removing the coal. The midnight to morning or "Hoot-Owl" shift works on cleanup operations. These miners are headed for the company shower room to clean up before going home. The younger miners run to the showers and knock down anyone in the way; the older miners walk, April 1974

View of the town of Raleigh, West Virginia, a suburb of Beckley, showing some of the homes and a portion of the railroad tracks used to carry coal from the mines to industry throughout the country. Raleigh was a mining headquarters in the past. New mines are opening around Beckley and should give a boost to the economy, July 1974

Early morning light enriches a bucolic scene at Claypool Hill, near Richlands, Virginia, about a dozen miles from the coal mines, October 1974

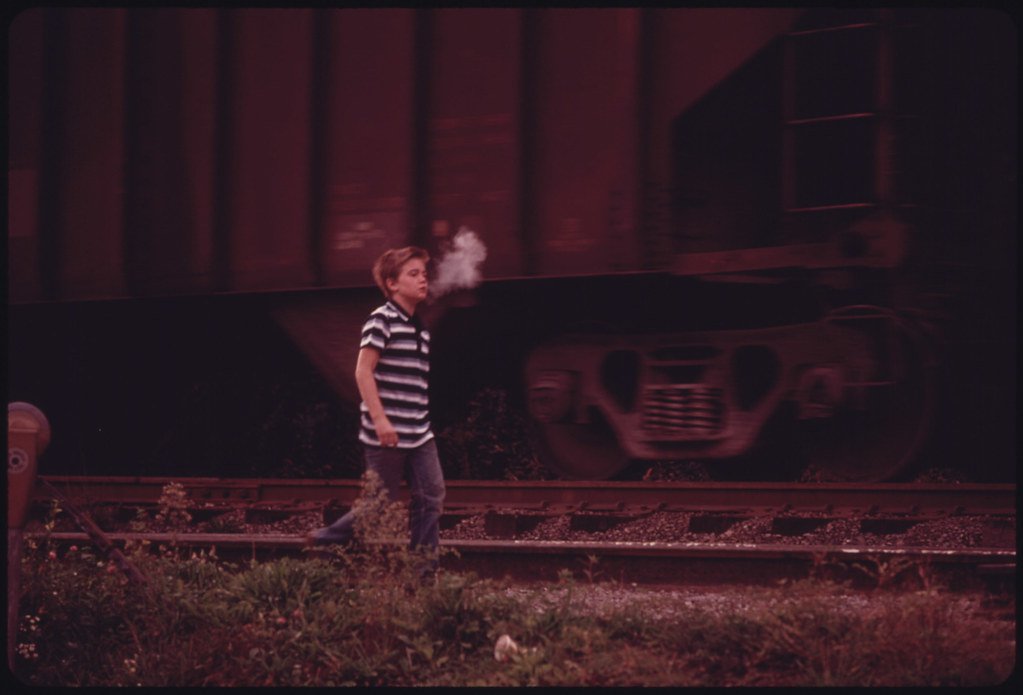

The cool morning air condenses a boy's breath as he walks along a coal car on his way to school in Cumberland, Kentucky, in Harlan County. Coal mining remains the largest single industry in the area. When the youngsters grow up many of them face the choice of working in coal-related jobs or moving away from the area, and family and friends, October 1974

Houses in Besoco, West Virginia, near Beckley. Their condition mirrors the decline of the once busy mining town. The mines are no longer worked there. The people who remain behind mostly are those receiving Black Lung, Social Security, pension or welfare benefits, July 1974

J.L. Bolen, 74, a blind, retired coal miner Is accompanied on a walk for fresh air by his wife in Besoco, West Virginia, near Beckley. He also likes to walk at night. Bolen was born in Besoco, named for the coal company that used to mine there. He started in the mines at age 14, and now gets Black Lung benefits as well as a United Mine Workers pension, May 1974

The main street through the small mining town of Rhodell, West Virginia, near Beckley. Coal is the only industry here and in other similar towns. Unless the youths want to go into coal-related Jobs, they are faced with searching for employment in the cities some distance away. This can be a heart-wrenching prospect to all members of the closeknit families, July 1974

Vicki Smith, 10, daughter of Mr. and Mrs. Jack Smith of Rhodell, West Virginia, near Beckley, stands next to a religious tapestry in the family home. Smith lost both legs in a mine cave-in and fought 18 years before receiving workmen's compensation. He now operates a beer joint. Smith comes from a family of nine brothers and seven sisters. All the men, except an infant who died, went to work in the mines, July 1974

Jack Smith, 42, a disabled miner in Rhodell, West Virginia, is wheeled down the street by his daughter, Donna, 16, to the beer joint he operates. He had worked in the mines for one year when his legs were crushed in a roof cave-in, but it was 18 years before he received workmen's compensation for the accident. Under his arm Is the cash box he uses at the tavern. Smith is active in the union and has manned the picket lines in his wheelchair in the past, July 1974

Jack Smith, 42, left, Rhodell, West Virginia, near Beckley, was a miner disabled when a roof caved in who had to wait 18 years to get workman's compensation. He was 21 when injured and had worked one year in the mines. Of the nine boys and seven girls in his family all the males went Into the mines except one who died in infancy. Smith Is shown on the porch of the beer joint he operates. Seated with him are his brothers, Leo, 39, and twin, Roy, 42, April 1974

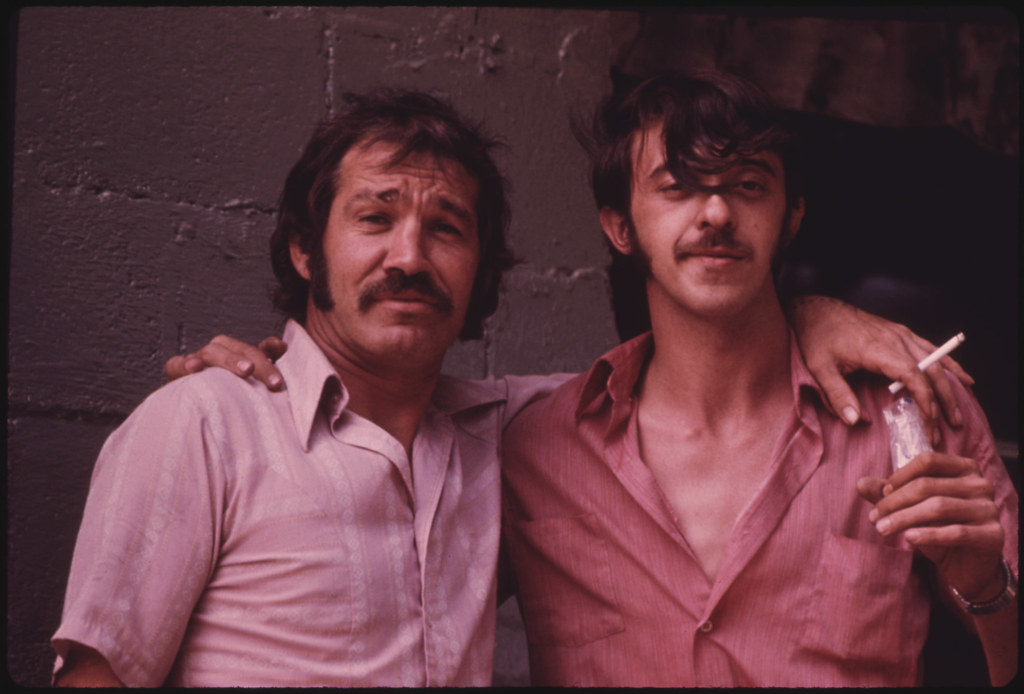

Two miners relaxing in a beer joint after finishing their shift. There is little to do in many of the small mining towns for the young men other than drink beer and talk. They are shown in the tavern operated by Jack Smith, Rhodell, West Virginia, near Beckley, June 1974

A tattered blanket hung on a line in Fireco, West Virginia, near Beckley, symbolizes the decline in the area after the coal mines gave out. The towns originally were built around the railroad tracks. The availability of such transportation made the mines possible, May 1974

Youngsters walk on ties of the railroad tracks that pass through Fireco, West Virginia, near Beckley. In the old mining communities the railroads always went through the center of the towns, which were built in the valleys around them. It was the railroads which made It possible to ship out the coal, the reason the towns were built. Fireco was in the middle of a once great coal area, but declined as the mines gave out, May 1974

Slag heap above housing on Buffalo Creek near Logan, West Virginia. Slag heaps are one of the items which make mining families mad. They can be ignited by spontaneous combustion, lightning, fire or a variety of other things, and burn indefinitely, April 1974

Coal slag heap burns above company houses near Hutchinson, West Virginia, near Logan, in the southern part of the state. Spontaneous combustion, lightning, a fire or a variety of other causes can result in ignition of these coal mine refuse piles, and they can burn for years. It Is one of the things that make the miners and their families mad, April 1974

Aerial view of clustered mobile homes used by families whose housing was wiped out in the early 1970's when an earthen dam gave way on Buffalo Creek near Man and Logan, West Virginia, and created a tidal wave that killed 104 people. Many of the homes in this Immediate area were washed away along with all the peoples' possessions, April 1974

Row of mobile homes near Madison, West Virginia, with trash thrown along the edge of the creek, a typical scene in the mining valleys that dot the area. The trailers are appealing to the young miners because they can be bought for less than conventional housing and take less space. Level land Is at a premium in the valleys, April 1974

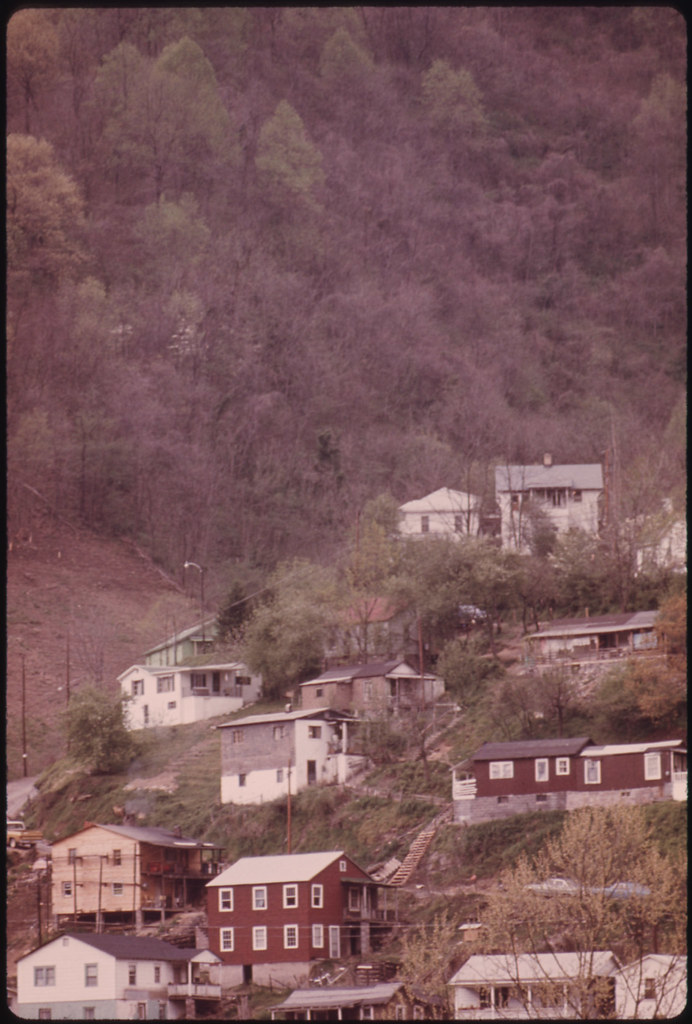

Houses perched on a hillside in Logan, West Virginia. Many homes are built on hilly ground because flat land in the valleys Is at a premium. Many of the younger mining families are buying mobile homes because they are cheaper than conventional housing and take up less space, April 1974

Kids playing outside a home in Sharples, West Virginia, north of Logan. Note the way the owner has built a place to park his car. Space is at a premium in the valleys of the mining area and this type of parking outside the home Is common, April 1974

Main street of Logan, West Virginia, showing a narrow street with parking on only one side which Is typical in many of the small towns in southern West Virginia, April 1974

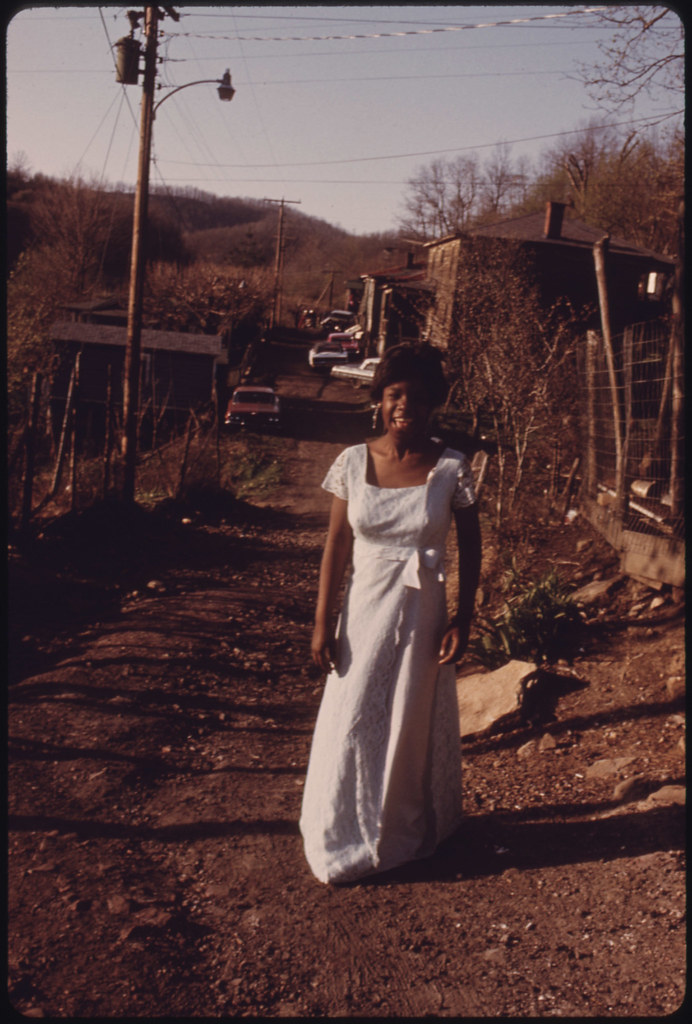

Dora Darlene Hancock, living in Fireco, West Virginia, near Beckley. The town Is divided between black and white populations by the railroad tracks. Dora Is walking up her street in a new dress on her way to a band concert at the local grade school, April 1974

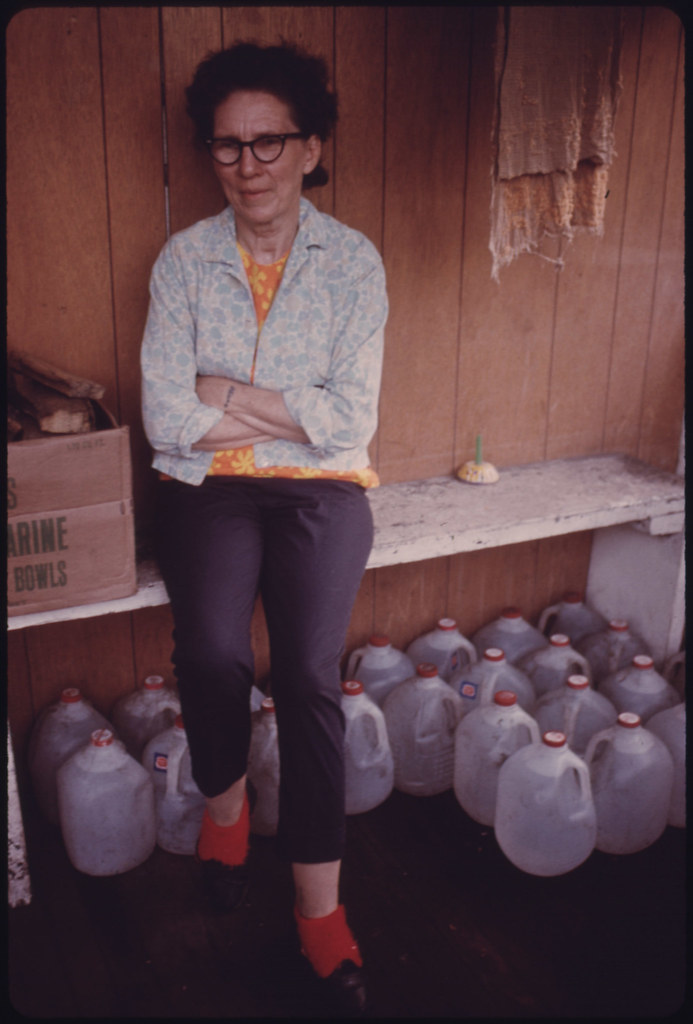

Alice Thompson, Besoco, West Virginia, Is shown with milk bottles. Her neighbors furnish her with water with after her water lines were cut off. She Is divorced From a coal miner who was imprisoned for killing a man, April 1974

Four young men gather in a beer joint in Clothier, West Virginia, near Madison. They are, left to right, Michael Doss, 18; Lanny Green, 21; Junior Jeffory, 20; and Robert Johnson, 18. All their parents work or have worked in the mine. Jeffory Is a mining foreman after two years, but does not like it and wants to join the Navy. Green can't find a job but would like to work for the railroad. Doss isn't working, but is waiting for a job in the mines, April 1974

Robert Johnson, 18, and Lanny Green, 21, outside a beer joint in Clothier, West Virginia, near Madison. They had been drinking beer and visiting with friends Inside. Johnson has passed a job physical and Is waiting to go to work in the mines. Green has not worked in the mines and isn't interested, but has not located a job. He would like to work for the railroad, April 1974

Robert Johnson, 18, sits on a pool table in a beer joint in Clothier, West Virginia, near Madison. He has passed a job physical and is waiting to go to work in the mines. Many of the young men like to get together in the taverns and drink beer and talk. There Is little else to do in the small mining towns, April 1974

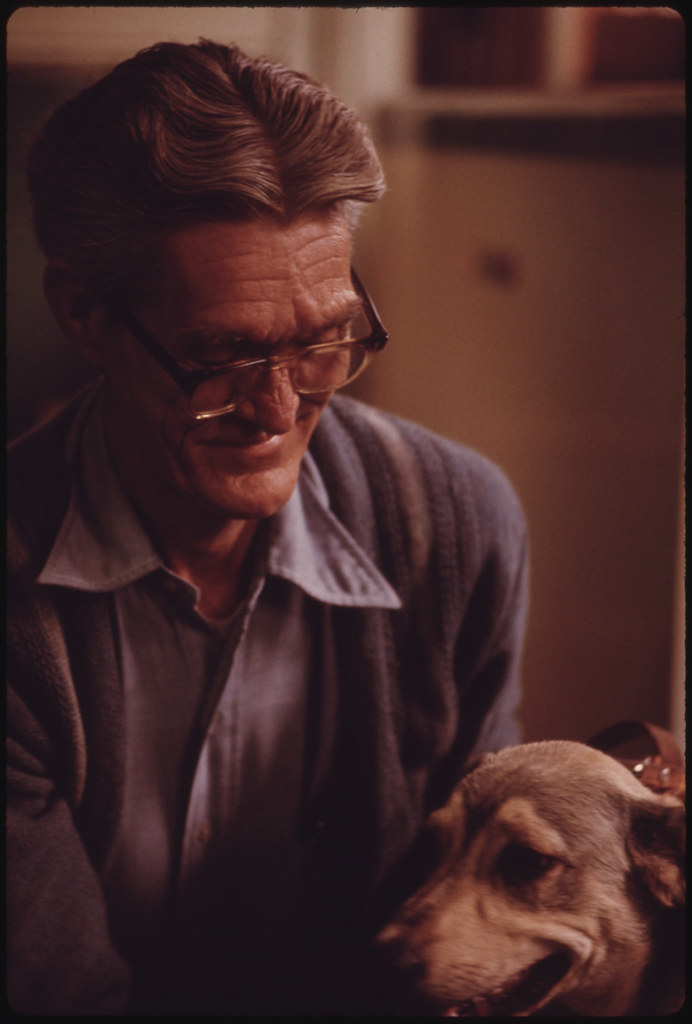

Edgar Zornes of Clothier, West Virginia, near Madison, with his dog. A miner for 23 years, he has Black Lung. Doctors have determined miners contract Black Lung from airborne particles of coal dust in the mines, which fill up air sacs in their lungs and

make it increasingly difficult to breathe, April 1974

Otis Saunders, in his late 80's, suns in front of his home in Fireco, near Beckley, West Virginia. Like most of the older men in the area, He Is a retired miner. Fireco was once a great mining town, but the region has been mined out, May 1974

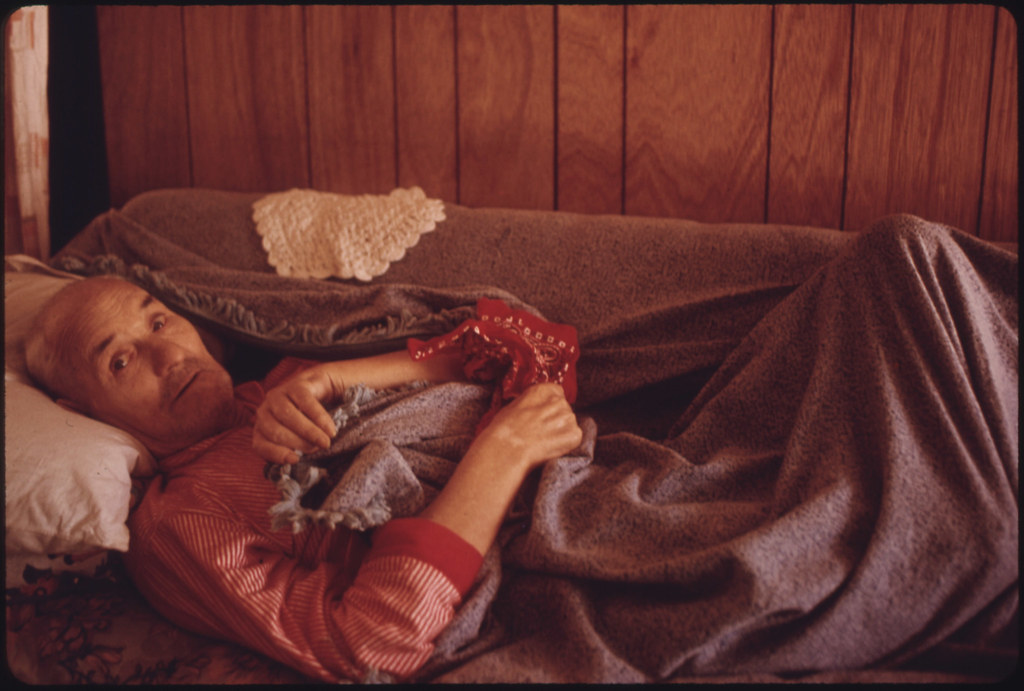

Ken Hatfield, 74, of Newton, West Virginia, near Charleston, in Mingo County. A World War Ii veteran, he began working in the mines at 18 and was employed underground at least 30 years. A sick man, he has lost one leg. He receives $78 a month in Social Security payments, plus a veteran's pension of $148 per month. Hatfield said he was having a tough time. Paul Bryant Is a neighbor and looks in on him, April 1974

One of the entrances to Chattaroy, West Virginia, near Williamson, leads past a Church of God. There are many small churches in the mining area and most have a fundamentalist belief. Chattaroy Is a small town with no industry. Most of the people survive on welfare, Social Security, pensions and Black Lung benefits, April 1974

Youngster returning to school after going home during recess to get an ice cream cone. The town of Chattaroy, West Virginia, near Williamson, Is small enough so the youngsters can do this. Many of them also go home for lunch. The town has no industry, and most of the people survive on welfare, pensions, Social Security and Black Lung benefits, April 1974

This pile of coal contains part of the one million tons kept on hand by the Tennessee Valley Authority steam plant at Cumberland City, Tennessee, near Clarksville. Coal for the furnaces arrives by barge and Is unloaded by automated equipment, July 1974

Coke furnaces at Keen Mountain, near Richlands, Virginia. Made from coal, the coke will be sent for use in the furnaces at the steel mills, April 1974

Aerial of Williamson, West Virginia, showing the coal rail yards and the river that divides Kentucky, at the upper left, and West Virginia. The town has the largest coal train yard in the world, followed by Danville, West Virginia, April 1974

Photos by Jack Corn (1929-) for the Environmental Protection Agency's Documerica Project (U.S. National Archives)

Merle Travis: Sixteen Tons (first recorded 1946)

ReplyDeleteForty-Two Years: A Original Song about Coal Mining and Black Lung, by Nimrod Workman, Chattaroy, West Virginia ("Both lungs were blowed down/by breathin' bad air")

Nimrod Workman, in Harlan County, USA (1976), Barbara Kopple's documentary about coal miners' 1973 strike against the Brookside Mine of the Eastover Mining Company

Harlan County, USA (trailer for the 1976 Barbara Kopple documentary)

Harlan County 7/6/2010: Steve Earl --"I'm gonna get out of here someday"

Again such wonderful photos, poem. I really like the way you combine text and photo, and the research behind. A lot of work. From one underground to another one...

ReplyDeleteMighty grim, Tom.

ReplyDeleteSixteen tons--Tennessee Ernie Ford.

When the oil runs out, and nuclear has finally been abandoned, the coal will be the fall-back energy.

First-hand reports tell us living in a coal-rich environment was oppressive. London in the 19th Century was like Purgatory. Householders would have to take down the heavy Victorian curtains and wash off the accumulated black soot periodically. The air in London was like "pea soup"--black pea soup. Black dust everywhere. People with all kinds of respiratory disorders. What with the heavy humidity of the British Isles, and all that coal soot, it must have been a dreary place.

Re: Steve Earl

ReplyDeleteAll of this, TC, all of this is what drew my Grandfather, a teacher no less, "out of (t)here" to far-away sleeping on depression era Detroit park benches for a chance to do something, anything else.

For his trouble, as was the fate of any production foreman/supervisor at the time, he graciously spent his "free" weekends tending the expansive lawn and painting/repainting the mansion's outbuildings on the Briggs Bloomfield Hills family estate.

Years later, I spent an afternoon inside that by then time-ravished, leaky Big House wondering which rooms he might have plastered.

“. . . to account for the human price . . .”

ReplyDeleteTwo years ago, big coal companies in the region formed a dummy corporation to buy up all union contracts. Now the dummy (Patriot Coal) is declaring bankruptcy so it won’t have to pay health benefits to retired union miners, and to escape other contractual obligations as well.

Thank you Marie, that means a lot, your marvelous weddings of word and text have been an inspiration -- a revelation, really.

ReplyDeleteKent, the Steve Earle plaint seems to give voice to the trapped young men in those mined-out towns captured in Jack Corn's eloquent series -- everyone, as per your report, requiring but not getting that elusive "chance to do something, anything else".

Curtis, The Tennessee Ernie hit single version of the song came out nine years after Merle Travis had recorded it on an album called Folk Songs of the Hills. The song is generally credited to Merle, though there is probably a prior source.

Travis said the chorus ("another day older and deeper in debt") came out of a refrain oft repeated by his father, a coal miner.

However the liner notes of a 1966 Folkways album by George E. Davis, a Kentucky coal miner turned folk singer, credit the song to Davis, who claimed to have writ the song in the 1930s.

The Davis version has interesting elaborations of the familiar lyric.

Lew Dite tenor banjo cover of George E. Davis version.

Hazen -- 'twas ever thus. As you would well know -- that's your precinct, after all.

So depressing. You drive through W. Va. now and there are all these signs for Clean Coal, a favorite myth of politicians.

ReplyDeleteGreat poem and photos.

If only there were light at the end. Somehow.

Nin,

ReplyDeleteClean Coal, games with words, round and round, squaring the circle that will always be broken.

And talking of... words... oops, Marie, the old miner/matchmaker meant to say "weddings of image and text"!

I thought so :-)) It made me smile.

ReplyDeletebut wedding of word and text.... has to be a happy one!

Marie,

ReplyDeleteWhat this post has been crying out for -- a smile!

But will the heavens ever smile upon the violated earth of Appalachia?

Much as one would wish to say the scenes captured by Jack Corn in the 1970s represent only a passing moment in the history of this part of the country, there's the sobering truth that the filthy business of coal extraction had been going on in this area long before he arrived with his camera ...and did not cease with his departure. As long as there is something remaining in the earth that the energy business wants, it's always going to be a case of (as the expression used to have it) Katy-bar-the-door.

Only the methods and scale of the operation have changed.

Just consider (for example) the meaning of the phrase "mountaintop removal mining".

Eight Billion Tons of What America Got Out of Kentucky (Eastern Coalfields, Then and Now)

the depth/ accumulation the pulmonary/ soot burden/ dead reckoning

ReplyDeleteAll those everyday dying breaths leading to such a density.

soot burden - those two words stick especially.

With Thatcher gone, I've been thinking about the Miner's Strike in the UK; what it meant for us on the left and at the same time how the industry wore at the lungs and the landscape and the air.

WB,

ReplyDeleteMany thanks.

Whether in navigational, mathematical, or (figurative) human terms, dead reckoning is of course a limited and faulty form of calculation.

But as limited and faulty creatures, what other kind have we got?

(And by the by, we'll be having no moments of silence for the Iron Lady here.)