.

This is what I see in my dreams about final exams:

two monkeys, chained to the floor, sit on the windowsill,

the sky behind them flutters,

the sea is taking its bath.

two monkeys, chained to the floor, sit on the windowsill,

the sky behind them flutters,

the sea is taking its bath.

The exam is the history of Mankind.

I stammer and hedge.

One monkey stares and listens with mocking disdain,

the other seems to be dreaming away --

but when it's clear I don't know what to say

he prompts me with a gentle

clinking of his chain.

the other seems to be dreaming away --

but when it's clear I don't know what to say

he prompts me with a gentle

clinking of his chain.

Wislawa Szymborska (1923-2012): Bruegel's Two Monkeys, translated from the Polish by Stanislaw Baranczak and Clare Cavanagh in Szymborska: View with a Grain of Sand: Selected Poems (1995)

Antverpia -- bird's eve view of the city of Antwerp (Brabant), 1572: Georg Braun and Frans Hogenberg, from thire atlas Civitates orbis terrarum, vol. 1, 1572; image by Walrasiad, 23 June 2010

Dwie malpy Bruegla

Tak

wygląda mój wielki maturalny sen:

siedzą w oknie dwie małpy przykute łańcuchem,

za oknem fruwa niebo

i kąpie się morze.

Zdaję z historii ludzi.

Jąkam się i brnę.

Małpa wpatrzona we mnie, ironicznie słucha,

druga niby to drzemie --

a kiedy po pytaniu nastaje milczenie,

podpowiada mi

cichym brzękaniem łańcucha.

siedzą w oknie dwie małpy przykute łańcuchem,

za oknem fruwa niebo

i kąpie się morze.

Zdaję z historii ludzi.

Jąkam się i brnę.

Małpa wpatrzona we mnie, ironicznie słucha,

druga niby to drzemie --

a kiedy po pytaniu nastaje milczenie,

podpowiada mi

cichym brzękaniem łańcucha.

Wislawa Szymborska (1923-2012): Dwie Malpy Bruegla (Bruegel's Two Monkeys), first published in Zycie Literackie, June 1957; text here given as appears in Szymborska's third volume of verse, Wolanie do Yeti (Waiting for the Yeti), July 1957

"We demand bread!": candid photo taken by secret police during Poznań protests: photographer unknown, June 1956; image by Jarekt, 5 December 2010

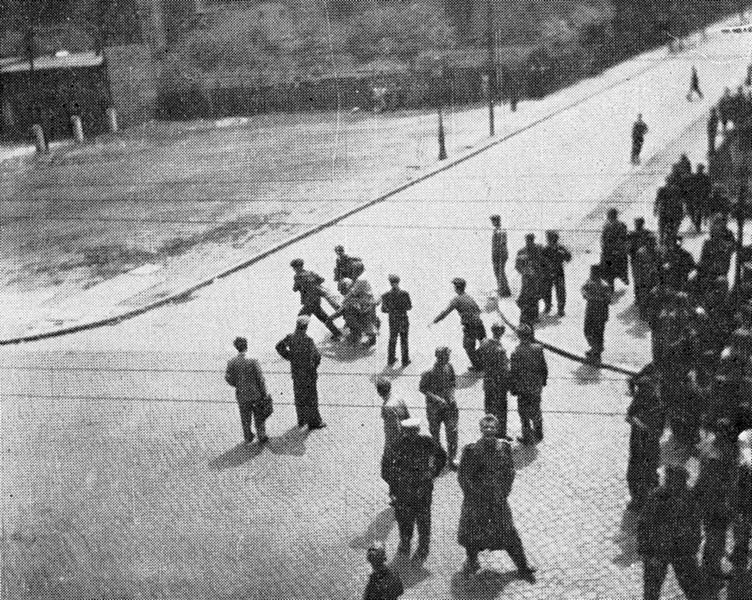

Kochanowskiego Street in Poznań; transporting one of the victims, June 1956: photographer unknown, from Jarosław Maciejewski, Zofia Trojanowicz: Poznański czerwiec 1956, Poznań 1981; image by Belissarius, 17 November 2011

Funeral of one of the victims, Poznań protests, June 1956: photographer unknown, from Jarosław Maciejewski, Zofia Trojanowicz: Poznański czerwiec 1956, Poznań 1981; image by Belissarius, 17 November 2011

Soviet tanks and empty Joseph Stalin Square in Poznań, June 1956: photographer unknown, from Jarosław Maciejewski, Zofia Trojanowicz: Poznański czerwiec 1956, Poznań 1981; image by Belissarius, 17 November 2011

Capuchin Monkeys (Cebus capucinus, from Cebus apella group), sharing: photo by Frans de Waal, from K. Powell, Economy of the Mind, 2003; image by Ayacop, 2006

In Szymborska's poem the speaker experiences trepidation when confronted by her graduation exam; she appears to be failing. She stammers and falls silent when asked about the history of humanity. A monkey rattles its chain, and, perhaps, a conversation begins.

ReplyDeleteIn 1956 Polish workers' riots and student protest demonstrations led to crisis, with Soviet troops massed menacingly along the border; only an October compromise allowed Poland to avoid the fate of Hungary.

Bruegel's Two Monkeys appeared in the Polish literary weekly Zycie Literackie in June 1957. It came out again in July, in Szymborska's third collection, Waiting for the Yeti.

Bruegel's small 1562 panel of two chained monkeys presents its subjects confined within an aperture opening upon a view of Antwerp's harbour. Bruegel spent much of the decade in Antwerp, in a time when that city was ruled by the Spanish Habsburg dynasty, and was operated as the central money market of Europe under German merchants like the Fuggers and Welsers of Augsburg. Luxury imports arriving at Antwerp harbour woud have included rare specimens from Africa, such as these monkeys, which Bruegel painted with obvious care for detail.

ReplyDelete"Antwerp's second boom was launched by the increase in exports of silver from South America via Seville. By 1537, silver was so abundant in Spain that Charles V's government was forced to revalue gold: the gold/silver ratio went up from 1:10.11 to 1:10.61. This influx in wealth gave Spain (or more properly Castile) a new economic and political dimension. The Habsburg dynasty, in the person of the emperor Charles V, found itself master not only of Spain but of the Netherlands, the empire and Italy which been firmly under its control since 1535. Being obliged to pay out sums of money all over Europe, the emperor had had dealings since 1519 with the merchant-moneylenders of Augsburg, whose real centre of operations was Antwerp. It was the Fuggers and the Welsers who raised and transported the money without which there would have been no imperial policy. In the circumstances, the emperor could not do without the services of the Antwerp money market which was being created between 1521 and 1535, precisely during the period when trade was in the doldrums and loans to the sovereign were the only fruitful means of employing capital -- which was not uncommonly being lent at rates of over 20%...

"The years 1535-57 unquestionably correspond to the high point of Antwerp's career. Never had the city been so prosperous. It was constantly expanding: the population had been no more than 44,000 to 49,000 in 1500, in the early days; by 1568 it was probably 100,000, and the number of houses had virtually doubled, from 6800 to 13,000. The city was covered with building sites, as new squares were designed, new streets (almost 8 kilometres of them) cut across the old -- in short as a new economic infrastructure with several centres was constructed. Luxury, capital, industrial activity and culture all blossomed together. Ad of course, there was the other side of the coin: rising wages and prices, with a growing gap between the rich who became richer and the poor who became poorer, as the numbers swelled of the proletariat of unskilled labourers -- porters, unloaders, errand-boys. The deterioration of conditions found its way into powerful guilds where wage-labour was gaining ground over independent craft production. The tailors' guild in 1540 included over a thousand unskilled or semi-skilled workers -- far cry from the restrictive code of Ypres in the old days. Manufactories were set up in new industries: sugar and salt, refineries, soap-making, dye-works; these employed poor wretches at derisory wages, barely 60% of a skilled worker's pay. The mass of unskilled labour undoubtedly curtailed the possibility of striking, which remained the weapon of the skilled worker. But if there were few strikes, there were or would be one day explosions of anger and violent revolts.

"Antwerp's second period of prosperity came to an abrupt end with the Spanish state bankruptcy of 1557, a bankruptcy which affected all the countries ruled by Spain... The financial circuit which had been supporting Antwerp collapsed and never really recovered again: the German bankers lost their position in Castilian finances where their place was taken by the Genoese. The age of the Fuggers was over."

-- Fernand Braudel: from The Perspective of the World (Le Temps du Monde), 1979, Volume 3 of Civilization and Capitalism, 15th-18th century (Civilisation materielle économie et capitalisme); translated from the French by Sîan Reynolds, 1984

he prompts me with a gentle

ReplyDeleteclinking of the chain

Antwerp guilds and Poznan protesters. Maybe de Waal's monkeys are quietly ringing out a reminder of their own unfreedom.

Tom - The 'History of Mankind' is a tough exam topic anywhere, nowhere more so than Poland as the Poznan photos you posted testify.

ReplyDeleteSzymborska's fondness for apes and other animals can be seen in the postcard collages she created:

http://serendipityproject.wordpress.com/2012/03/03/mar-3-2012-a-gallery-of-twenty-nine-postcard-collages-and-portraits-i-m-wislawa-szymborska-1923-2012/#jp-carousel-6022

-David

Monkey see, monkey no do.

ReplyDeleteI so appreciated this and will certainly be spending time with it all week. Thank you for posting the poem in Polish also, a language I know very little about, but am trying to "sound" my way through. There's so much here and any encounter with Capuchin monkeys is fine with me. Years ago I remember being in the Central Park Zoo in Manhattan and being importuned closer by a Capuchin to its enclosure. He had the most intelligent and thoughtful face and he really caught me in his gaze to the point that I was utterly surprised when he grabbed the can of Coke out of my hand, receded a bit into the cage and enjoyed the rest of it. The other Capuchins seemed to enjoy the scene and I was grateful that the zookeepers didn't see any of this. I really wasn't trying to break any rules and the monkey clearly knew that even if the signs outside the cage applied to him also, he wasn't violating the rule against feeding the animals. Curtis

ReplyDeleteMany thanks, friends, for your patience with the historical aspects and dimensions of these arts of word and picture: the frame in which imagination must inevitably play itself out, in all ages.

ReplyDeleteCurtis, there's a wonderful irony in this:

"I really wasn't trying to break any rules and the monkey clearly knew that even if the signs outside the cage applied to him also, he wasn't violating the rule against feeding the animals."

David, those collage postcards are a revelation of the playful side of Szymborska's poetic imagination.

A form of inspired "monkeying with" things as they are...

Collage postcard, Wislawa Szymborska to Wandy Klominkowej, 1984

(na swiecie, aby osiagnac sukces, trzeba uchodzic za... = in the world, to achieve success you have to pass for...?) )

And the poet's abiding, rueful consciousness of the perilous fate it is to be an isolated, vulnerable sentient organism caught up in the murderous tides of history is captured succinctly in this one:

Collage postcard, Wislawa Szymborska to Jerzego Zagorskiego, 1979

(nie upadamy na duchu = do not lose heart)

Encouraged by the good response to the work of this great world poet, another offering:

Wislawa Szymborska: Nothing's a Gift

Charles North has a nice poem on the Bruegel painting...

ReplyDeleteWHAT IT IS LIKE

Two pensive monkeys chained heartbreakingly to a metal ring in a high, thick-walled window arch (no glazing) which looks out behind on a pale harbor and filmy blue and green city in the far distance. Clearly the monkeys are conscious; have consciousness. We know what it is like for them to have given up hope and to look only inward, while appearing to stare at the ring imprisoning them and the space just below the window in front, between it and us.

http://www.charlesnorth.net/site/Home.html

I don't wish to argue with Charles North, but the monkeys have not given up hope. They're thinking, that's all. They are spirited, indomitable, sentient thinking beings. Curtis

ReplyDelete