.

Dancing Bear, State Fair of Texas: photo by Lynn Lennon, 1985 (Southern Methodist University, Central University Libraries, DeGolyer Library)

Stond who so list vpon the Slipper toppe

...Of courtes estates and lett me heare rejoyce

And vse me quyet without lett or stoppe

...Vnknowen in courte that hath suche brackishe ioyes

.....In hidden place so lett my dayes forthe passe

...That when my yeares be done withouten noyse

.....I may dye aged after the common trace

Ffor him death greepthe right hard by the croppe

...That is moche knowen of other and of him self alas

...Doth dye unknowen dazed with dreadfull faceThomas Wyatt (1503-1542): Stond who so list vpon the Slipper toppe, c. 1540 (text from Arundel Harington ms.)

1 Slipper = slippery. Cf. Wyatt's translation of Plutarch, Quyet of Mind: "slypper riches".

1 toppe (culmine). Cf. Sir T. Elyot's version of the Seneca chorus.

3 use...stop. i.e., Comport myself quietly without hindrance or impediment from others [R. Rebholz].

4 Vnknowen in courte (nullis nota Quiritibus). Cf. Elyot: "Myyde unknowen".

4 that hathe suche brackish ioyes [Wyatt's addition to the Latin].

4 brackishe: being spoiled to the point of being nauseous by the mixture of the salty with the fresh [Rebholz].

6 withouten noyse (per tacitum): Elyot.

7 common (translates plebeius).

7 after the common trace: (1) a common way or path; (2) like other people. The Latin has "a common man" (plebeius) [Rebholz].

8 dazed with dreadfull face [Wyatt's addition].

8 dazed: (1) bewildered, stupefied (2) benumbed with cold.

8 croppe (crop): (1) bird's neck; (2) throat.

8 death...croppe: Latin has "Death lies heavy on him" (illi mors gravis incubat).

10 unknowen (ignotus): Elyot.

Side show attraction, State Fair of Texas: photo by Lynn Lennon, 1985 (Southern Methodist University, Central University Libraries, DeGolyer Library)

Seneca: Chorus 2: from Thyestes

Stet, quicumque volet, potens

aulae culmine lubrico:

me dulcis saturet quies.

obscuro positus loco

leni perfruar otio;

nullis nota Quiritibus

aetas per tacitum fluat.

sic cum transierint mei

nullo cum strepitu dies,

plebeius moriar senex.

Illi mors gravis incubat

qui, notus nimis omnibus,

ignotus moritur sibi.

Lucius Annaeus Seneca (c 4 BC-AD 65), Thyestes, ll. 391-403

Outdoor ice show, "Pepsi on Ice", State Fair of Texas: photo by Lynn Lennon, 1985 (Southern Methodist University, Central University Libraries, DeGolyer Library)

Andrew Marvell: Senec. Traged. ex Thyeste Chor. 2

...Stet quicunque volet potens

...Aulae culmine lubrico &c.

...Aulae culmine lubrico &c.

...........Translated.

Tottering Favour's slipp'ry hill.

All I seek is to lye still.

Settled in some secret Nest

In calm Leisure let me rest;

And far off the publick Stage

Pass away my silent Age.

Thus when without noise, unknown,

I have liv'd out all my span,

I shall dye, without a groan,

An old honest Country man.

Who expos'd to others Eyes,

Into his own Heart ne'r pry's,

Death to him's a Strange surprise.

Andrew Marvell (1621-1678): The Second Chorus from Seneca's Tragedy, Thyestes (probably composed after 1668; published posthumously 1678)

State Fair of Texas: photo by Lynn Lennon, 1985 (Southern Methodist University, Central University Libraries, DeGolyer Library)

John Norris: The Choice (after Seneca)

No, I shan't envy him who're he be

That stands upon the Battlements of State;

....Stand there who will for me,

....I'd rather be secure than great.

Of being so high the pleasure is but small,

But long the Ruin, if I chance to fall.

Let me in some sweet shade serenely lye,

Happy in leisure and obscurity;

....Whilst others place their joys

....In Popularity and noise.

Let my soft moments glide obscurely on

Like subterraneous streams, unheard, unknown.

Thus when my days are all in silence past,

A good plain Country-man I'll dye at last;

....Death cannot chuse but be

....To him a mighty misery,

Who to the World was popularly known,

And dies a Stranger to himself alone.

John Norris (1657-1711), The Choice (after Seneca)

Carousel, State Fair of Texas: photo by Lynn Lennon, 1985 (Southern Methodist University, Central University Libraries, DeGolyer Library)

Stuffed pony prizes hang from game booth, State Fair of Texas: photo by Lynn Lennon, 1985 (Southern Methodist University, Central University Libraries, DeGolyer Library)

Dancing Bear, State Fair of Texas: photo by Lynn Lennon, 1985 (Southern Methodist University, Central University Libraries, DeGolyer Library)

Big Tex is the symbol of the State Fair of Texas: photo by Lynn Lennon, 1985 (Southern Methodist University, Central University Libraries, DeGolyer Library)

State Fair of Texas: Tower building houses executive offices and food concessions: photo by Lynn Lennon, 1985 (Southern Methodist University, Central University Libraries, DeGolyer Library)

Surgery, Portuguese Institute of Oncology, Lisbon. Architect: Hermann Distel. Conception of project: 1938. Period of construction: 1940-1953. Opening: 1954: photo by Estúdio Horácio Novais, 1950(?)-1953 (Biblioteca de Arte / Art Library Fundaçao Calouste Gulbenkian)

Hospital of Santa Maria, Lisbon. Architect: Hermann Distel. Conception of project: 1938. Period of construction: 1940-1953. Opening: 1954: photo by Estúdio Horácio Novais, 1950(?)-1953 (Biblioteca de Arte / Art Library Fundaçao Calouste Gulbenkian)

Crowd in Rua do Carmo, Lisbon: photo by Estúdio Horácio Novais, 25 April 1974 (Biblioteca de Arte / Art Library Fundaçao Calouste Gulbenkian)

Members of the NSB (Dutch national

socialist party) and shaven 'kraut girls' are being brought in by

members of the Dutch Resistance. Deventer, The Netherlands: photo by Willem van de Poll, 11 April 1945 (Anefo photo collection / Nationaal Archief)

Grande Hotel da Figueira da Foz, Portugal Aechitect: Inácio Peres Fernandes. Opened 1953: photo by Estúdio Horácio Novais, 1950s (Biblioteca de Arte / Art Library Fundaçao Calouste Gulbenkian)

In [Wyatt's] finest imitations... historical consciousness goes... further. Imitation becomes fully heuristic and frequently dialectical; it takes the full responsibility for its cultural moment and location, "in Kent and Christendome," with the vulnerabiity as well as the strength these involve. To demonstrate this degree of consciousness, one need only cite the superb little version of Seneca, doubtless written after the execution of Wyatt's patron [Thomas] Cromwell [in 1540]... this derives from a chorus of Seneca's Thyestes... Wyatt Englishes this by suppressing the Latin leni... otio, the easy leisure that calls up an aristocratic Roman villa. Wyatt's language identifies him as an Anglo-Saxon countryman whose quietude will not be voluptuous, and whose death will not simply go unremarked, nullo cum strepitu, but whose obscurity will adhere to the traditional manner of ordinary folk, "after the common trace". "Trace" is itself one of those rustic words that help to situate the speaker. Wyatt omits the hint of sensual satisfaction in Seneca's saturet, adds the powerful modifier "brackishe" (salty, nauseating) in his fourth line, plays the force of "rejoyce" against the sobriety of "quyet", with its echo of the poet's translation of Plutarch, The Quyet of Mynde. Above all, Wyatt rewrites the closing lines, roughening Seneca's neat antithesis in ll. 12-13 and suppressing his sinister image of suffocation (incubat -- settles down upon, broods upon like a bird) for the more violent clutch of Death's abrupt hand: "him death greep'the right hard by the croppe." The five stressed monosyllables in unbroken sequence violate the rhythmic pattern with a wrench that corresponds to the action, and the harsh Anglo-Saxon words maintain the identity of a speaker hidden in the countryside outside a Latinate court. The control of verse movement, expert throughout, culminates in the majestic rallentando of the last line and a half, its terrible subsiding intensified by the pitiless alliteration. Brilliantly, Wyatt chooses not to explain why the lack of knowledge renders death's grip so much harder, not to explain the brilliant concluding phrase, his own addition -- "dazed with dreadfull face". The great man is "dazed" -- stupefied, bewildered, numbed -- because death's assault has been so sudden, because its numbing physiological effect has already begun or is completed, because we can assume the dying man has fallen from the slipper top of eminence, and perhaps because in his naive egoism he had thought of himself as immune from mortality. He is "dreadfull" -- inspiring reverence, awe, fear -- because as a power at court he has always inspired those, because he is suffering the humiliation of death after so much sway, because conceivably he has been publicly executed like Cromwell, and because, most profoundly, he is suffering this death in the limelight without the redeeming possession or acquisition of self-knowledge; he remains "of him self... unknowen." Wyatt's use of the Latin chorus only serves to help him find an idiom that is radically anti-Latinate and calls attention to its own parochial rusticity; his use of the somewhat facile Stoic morality helps him to adumbrate a drama of his own time and place. By insisting on its English provincialism the text assumes a vulnerability toward the elegant classicism of its subtext, and only by accepting this vulnerability can it implicitly criticize the subtext's facility. This is an intensely Tudor poem and conscious of itself as such, awake to the dialectical distinctions it has created. By achieving this degree of control over potential anachronism, Wyatt made it possible for the first time to speak of mature English imitation.

Thomas M. Greene, from The Light in Troy: Imitation and Discovery in Renaissance Poetry, 1982

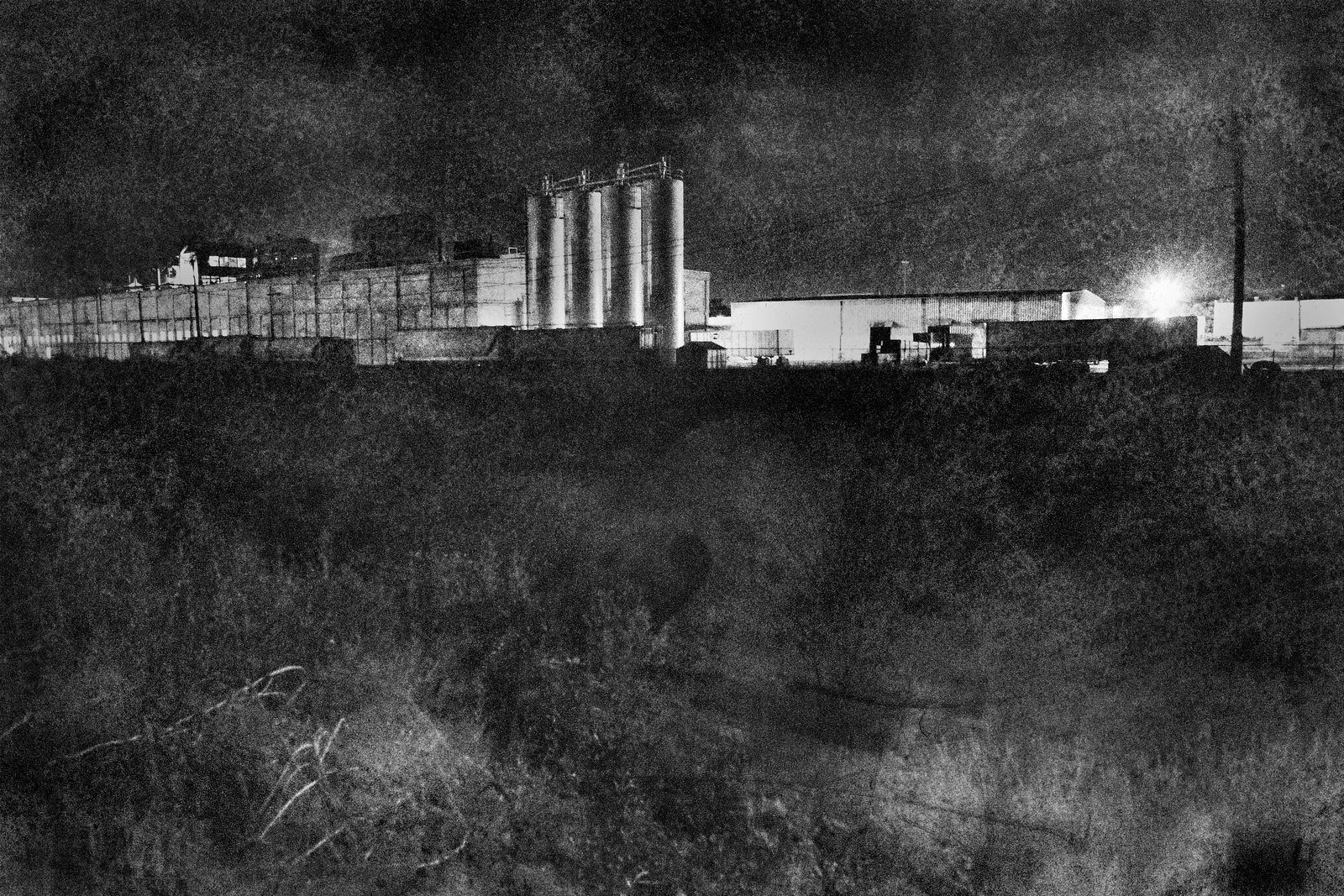

Factory, Dogtown (St. Louis): photo by chalkdog, 7 September 2013

Utility poles in moonlight, Dogtown (St. Louis): photo by chalkdog, 18 September 2013

Act of State. Vidkun Quisling. Torchlight procession: photographer unknown, 1 February 1942 (National Archives of Norway)

shinjuku, tokyo: photo by wire_paladinSF, 10 April 2014

Wow! I need to spend much more time with these texts and images, and the stories they tell. For the moment, transfixed by the chalk dog photo of utility poles in Dogtown, St. Louis.

ReplyDelete-David

David,

ReplyDeleteMany thanks for looking. Yes, have we not all been mesmerized, one way or another, by the utilities, indeed by the entire infrastructure, of St Louis, these past few weeks... and chalkdog, as a denizen, has been watching even longer.

I suppose that would have to qualify him as an expert witness.

Many of these photos have a certain "depth", historically speaking, as I suppose must be obvious. It's not an indecipherable code -- the past, that is -- but I do think the ability (or time, or willingness) to sort it out grows scarcer by the day... unlike, say, the code of the Ice Bucket Challenge.

Which would probably resolve down to the Celebrity Index.

(Or is that too a part of history... in the making?)