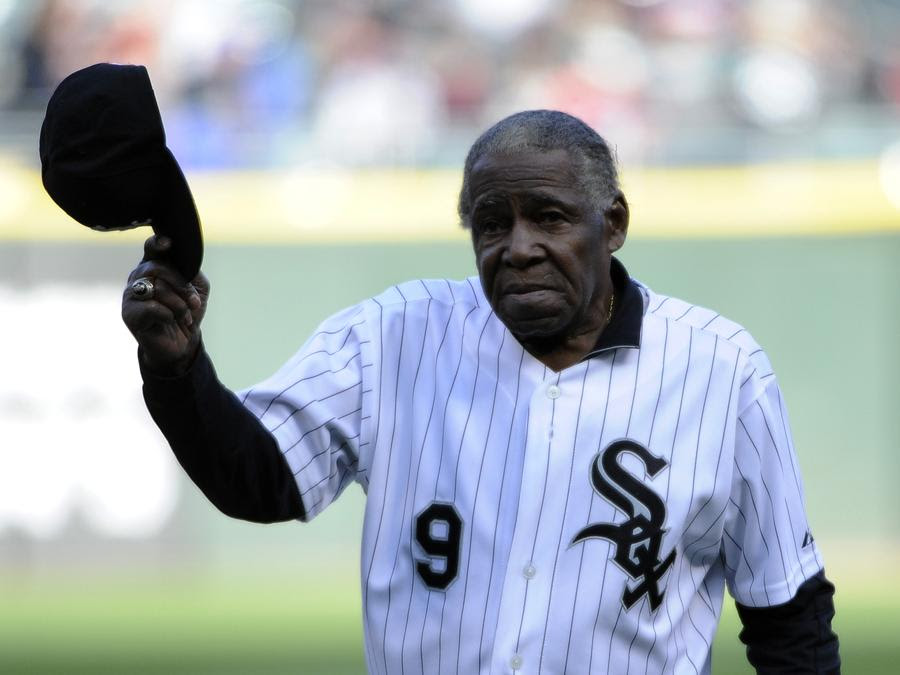

Nobody looked like they were having more fun #RIPMinnie: image via Matt Rodewald @MattRodewald, 1 March 2015

Saturnino Orestes Armas Miñoso Arrieta. He was the best ballplayer I ever got to see up close, on a regular basis. I worked at the ballpark. I

got to see him play 60-70 times a year, in his prime -- or as close to

it as he was going to be, having left his youth and no doubt some of his

best years in Cuba and the Negro League. His famous friendly disposition was no act; he was

cool with everybody. He had to be. He also possessed a kind of natural

happy

swagger that was new. Off the field, the flashy shirts and hats and ties. The big

green convertible. His abilities made all that extravagance possible.

But he was as

tough as any player who had ever played the game. He had to be. Now

there is

talk of five-tool players. Minnie had the standard five -- run,

throw, play the field, hit, hit with power -- plus some others that were

at least equally important: the personal and cultural skills that

allowed him to endure the racial abuse that came as a matter of course

in that time, place and situation. He let it all roll off, kept on

smiling anyway. Pitchers feared him and threw at him mercilessly, but he

refused to back off the plate, even after one particular "purpose

pitch", delivered a bit too purposefully, fractured his skull. He missed

a couple of weeks, came back attacking at the plate as before. His attitude was, Bring it on.

He ran the bases just as aggressively, with an edge and abandon that

surprised opponents, routinely stretching singles

into doubles, doubles into triples, giving outfielders bad dreams. His

daring as a basestealer distracted and aggravated opposing pitchers and

managers, but proved contagious in his own team. The traditionally lame

and near-inert White Sox suddenly became a very interesting team;

sparked by Minnie's example, everybody was stealing bases; the old

ballpark in its mean South Side precinct, over which, on sultry summer

nights, the prevailing breezes from the prairie always seemed to waft

the choking reek of the stockyards, was now awake with a new energy,

crowds chanting Go! Go! Go! into the stinking night whenever a

White Sox player reached base. Meanwhile Minnie, who had initiated all

this, continued giving the impression he was enjoying everything

enormously. Of course one understood he had left family behind in Cuba,

and that he was troubled by having done so. There had to be things he

was holding to himself. Yet, that wonderful sunny demeanour. His

English wasn't very good, but his teammates seemed to think the things

he said were charming and funny, though they could only half-understand.

A little thing like English wasn't going to hold Minnie back. Given

how far he'd had to come to get where he was, really nobody was going to

get him to back off ever.

Minnie was hurt by being left out of the Hall of Fame. He is the finest player ever to have the honour of being left out of that elite company. His absence makes it seem just that little bit less elite. Last year he made it into the baseball Hall of Fame in his native country, however. Safely home at last.

Perico, Matanzas, Cuba: photo by Denise Diaz via Spirited Pursuit, 8 July 2014

Legendario pelotero cubano Minnie Miñoso murió en Estados Unidos:

El cubano Minnie Miñoso, oriundo de la occidental provincia de

Matanzas, fue seleccionado a nueve Juegos de Estrellas y ganador de tres

Guantes de Oro en las Grandes Ligas: Juventud Rebelde, 1 de Marzo del 2015

WASHINGTON, marzo 1.— El expelotero cubano Orestes Miñoso, primer latino negro en jugar en las Grandes Ligas de Estados Unidos, falleció este domingo en el condado de Cook, Illinois, reporta PL.

Minnie Miñoso, como era conocido, debutó en 1949 con los Indios de Cleveland, dos años después que el estadounidense Jackie Robinson rompiera la barrera racial con los Dodgers de Brooklyn.

El jardinero, oriundo de la occidental provincia de Matanzas, fue cambiado en 1951 a las Medias Blancas de Chicago, equipo con el cual se estrenó conectando un jonrón en su primer turno al bate, el 1 de mayo contra el diestro de los Yankees de Nueva York Vic Raschi.

Aquel cuadrangular fue el primero de los 135 en 12 torneos con Chicago, al que tributó también un promedio ofensivo de .304 y 808 carreras impulsadas.

La franquicia de la Windy City (Ciudad de los Vientos) retiró en 1983 el número 9 utilizado por Saturnino Orestes Armas Miñoso Arrieta, su nombre completo, cuya estatua aparece en el U.S. Cellular Field.

En Cuba, el beisbolista fue nombrado Novato del Año en su primera temporada (1945-1946), ganó dos pergaminos de Jugador Más Valioso (1952-53 y 1956-57), además de conquistar un título de bateo y varios lideratos en carreras anotadas, triples y bases robadas con los Tigres de Marianao.

Miñoso, seleccionado a nueve Juegos de Estrellas y ganador de tres Guantes de Oro en las Grandes Ligas, no llegó a Cooperstown, el Salón de la Fama del béisbol estadounidense, un templo al que sus número lo catapultaron hace mucho tiempo ya.

El pasado año Miñoso fue incluido en el Salón de la Fama del béisboll cubano junto a Conrado Marrero y Camilo Pascual, quienes también brillaron en la Major League Baseball.

#Minoso #latinopride #Chicago #WhiteSox thank you, rest in paradise: image via Alberto Gomez @Betowskie, 1 March 2015

WASHINGTON, marzo 1.— El expelotero cubano Orestes Miñoso, primer latino negro en jugar en las Grandes Ligas de Estados Unidos, falleció este domingo en el condado de Cook, Illinois, reporta PL.

Minnie Miñoso, como era conocido, debutó en 1949 con los Indios de Cleveland, dos años después que el estadounidense Jackie Robinson rompiera la barrera racial con los Dodgers de Brooklyn.

El jardinero, oriundo de la occidental provincia de Matanzas, fue cambiado en 1951 a las Medias Blancas de Chicago, equipo con el cual se estrenó conectando un jonrón en su primer turno al bate, el 1 de mayo contra el diestro de los Yankees de Nueva York Vic Raschi.

Aquel cuadrangular fue el primero de los 135 en 12 torneos con Chicago, al que tributó también un promedio ofensivo de .304 y 808 carreras impulsadas.

La franquicia de la Windy City (Ciudad de los Vientos) retiró en 1983 el número 9 utilizado por Saturnino Orestes Armas Miñoso Arrieta, su nombre completo, cuya estatua aparece en el U.S. Cellular Field.

En Cuba, el beisbolista fue nombrado Novato del Año en su primera temporada (1945-1946), ganó dos pergaminos de Jugador Más Valioso (1952-53 y 1956-57), además de conquistar un título de bateo y varios lideratos en carreras anotadas, triples y bases robadas con los Tigres de Marianao.

Miñoso, seleccionado a nueve Juegos de Estrellas y ganador de tres Guantes de Oro en las Grandes Ligas, no llegó a Cooperstown, el Salón de la Fama del béisbol estadounidense, un templo al que sus número lo catapultaron hace mucho tiempo ya.

El pasado año Miñoso fue incluido en el Salón de la Fama del béisboll cubano junto a Conrado Marrero y Camilo Pascual, quienes también brillaron en la Major League Baseball.

#Minoso #latinopride #Chicago #WhiteSox thank you, rest in paradise: image via Alberto Gomez @Betowskie, 1 March 2015

Perico, Matanzas, Cuba: photo by Denise Diaz via Spirited Pursuit, 8 July 2014

Former MLB All-Star Minnie Minoso writes about his hopes for his home country: Time, 22 December 2014

When I heard the news that the United States and my home country, Cuba, were resuming diplomatic relations, I was so happy. I never thought this day would come in my lifetime. Though it took too long—I’m 90 years old—I’m thrilled to be here to see it. I’ve been an American citizen for 30 years. I have always loved living here. Playing major league baseball in America was my dream. But you always have a soft spot for the place where you were born.

I grew up on a sugar farm in Perico, a small town around 90 miles east of Havana. We were poor; we had no electricity, no radio. But I was raised in a loving family, and my parents taught me the values of hard work. Like my father, I worked in the sugar fields while growing up, but also knew I had baseball talent. Each sugar ranch had a baseball team, and I threw so hard—I was a pitcher back then -- that other players were afraid of facing me. We didn’t have real gloves. To pay for our uniforms, we would buy empty sugar boxes and resell them for a dollar profit. We gave our money to a woman who made them out of cotton flour sacks.

In 1945, I left Cuba to play in the Negro Leagues in the U.S. Some people warned me not to go to America, because of racial discrimination and segregation. But although segregation wasn’t as formal as it was in the United States, Cuba was no racial paradise. It was very, very difficult for black ballplayers to play professionally in Cuba.

As my major league career took off in the 1950s, I went home to Cuba every offseason, to play winter ball and visit my family. It was a golden age. Tourists vacationed in Cuba. Havana nightlife was thriving. You can’t overstate how big baseball was in Cuba.

A view of a rural road in Perico (Matanzas Province, Cuba). The street is just nearby the central gas station on the Carretera Central: photo by Der Borg, 18 January 2013

Things started to change once Fidel Castro came into power in 1959. I

was a ballplayer, not a politician. To me, you don’t prop up the poor

by taking away from the well-off. I feared the Cuban people would lose

their freedom, their hard-earned property.

In 1961, I made the painful decision to leave Cuba for good. I saw where the country was headed, and did not agree with the Castro’s policies. I said goodbye to my two sisters, and my father. I never saw them again.

This brought great pain. But I like to look at the positive: We are entering a new era. If my doctor says I’m healthy enough to fly, I plan on traveling to Cuba soon, to be inducted into a hall of fame. Maybe I’ll see some of the same trees, the same sugar fields, I remembered as a boy.

We still don’t know what this new policy means for Cuban baseball players. Will they be able to go to the majors, and have the same opportunities I did? Will baseball teams construct academies in Cuba, like they’ve done in the Dominican Republic? If I get to talk to any young up-and-coming Cuban baseball players, I will tell them: don’t try to escape. Be legal. Don’t risk it. Everything is going to work out now. Everything is going to be happy. -– as told to Sean Gregory

Minnie Minoso, a seven-time MLB All-Star, is the first black Cuban player to appear in the major leagues, and the only player to appear in a professional baseball game during seven different decades.

When I heard the news that the United States and my home country, Cuba, were resuming diplomatic relations, I was so happy. I never thought this day would come in my lifetime. Though it took too long—I’m 90 years old—I’m thrilled to be here to see it. I’ve been an American citizen for 30 years. I have always loved living here. Playing major league baseball in America was my dream. But you always have a soft spot for the place where you were born.

I grew up on a sugar farm in Perico, a small town around 90 miles east of Havana. We were poor; we had no electricity, no radio. But I was raised in a loving family, and my parents taught me the values of hard work. Like my father, I worked in the sugar fields while growing up, but also knew I had baseball talent. Each sugar ranch had a baseball team, and I threw so hard—I was a pitcher back then -- that other players were afraid of facing me. We didn’t have real gloves. To pay for our uniforms, we would buy empty sugar boxes and resell them for a dollar profit. We gave our money to a woman who made them out of cotton flour sacks.

In 1945, I left Cuba to play in the Negro Leagues in the U.S. Some people warned me not to go to America, because of racial discrimination and segregation. But although segregation wasn’t as formal as it was in the United States, Cuba was no racial paradise. It was very, very difficult for black ballplayers to play professionally in Cuba.

As my major league career took off in the 1950s, I went home to Cuba every offseason, to play winter ball and visit my family. It was a golden age. Tourists vacationed in Cuba. Havana nightlife was thriving. You can’t overstate how big baseball was in Cuba.

A view of a rural road in Perico (Matanzas Province, Cuba). The street is just nearby the central gas station on the Carretera Central: photo by Der Borg, 18 January 2013

In 1961, I made the painful decision to leave Cuba for good. I saw where the country was headed, and did not agree with the Castro’s policies. I said goodbye to my two sisters, and my father. I never saw them again.

This brought great pain. But I like to look at the positive: We are entering a new era. If my doctor says I’m healthy enough to fly, I plan on traveling to Cuba soon, to be inducted into a hall of fame. Maybe I’ll see some of the same trees, the same sugar fields, I remembered as a boy.

We still don’t know what this new policy means for Cuban baseball players. Will they be able to go to the majors, and have the same opportunities I did? Will baseball teams construct academies in Cuba, like they’ve done in the Dominican Republic? If I get to talk to any young up-and-coming Cuban baseball players, I will tell them: don’t try to escape. Be legal. Don’t risk it. Everything is going to work out now. Everything is going to be happy. -– as told to Sean Gregory

Minnie Minoso, a seven-time MLB All-Star, is the first black Cuban player to appear in the major leagues, and the only player to appear in a professional baseball game during seven different decades.

Perico, Matanzas, Cuba: photo by Denise Diaz via Spirited Pursuit, 8 July 2014

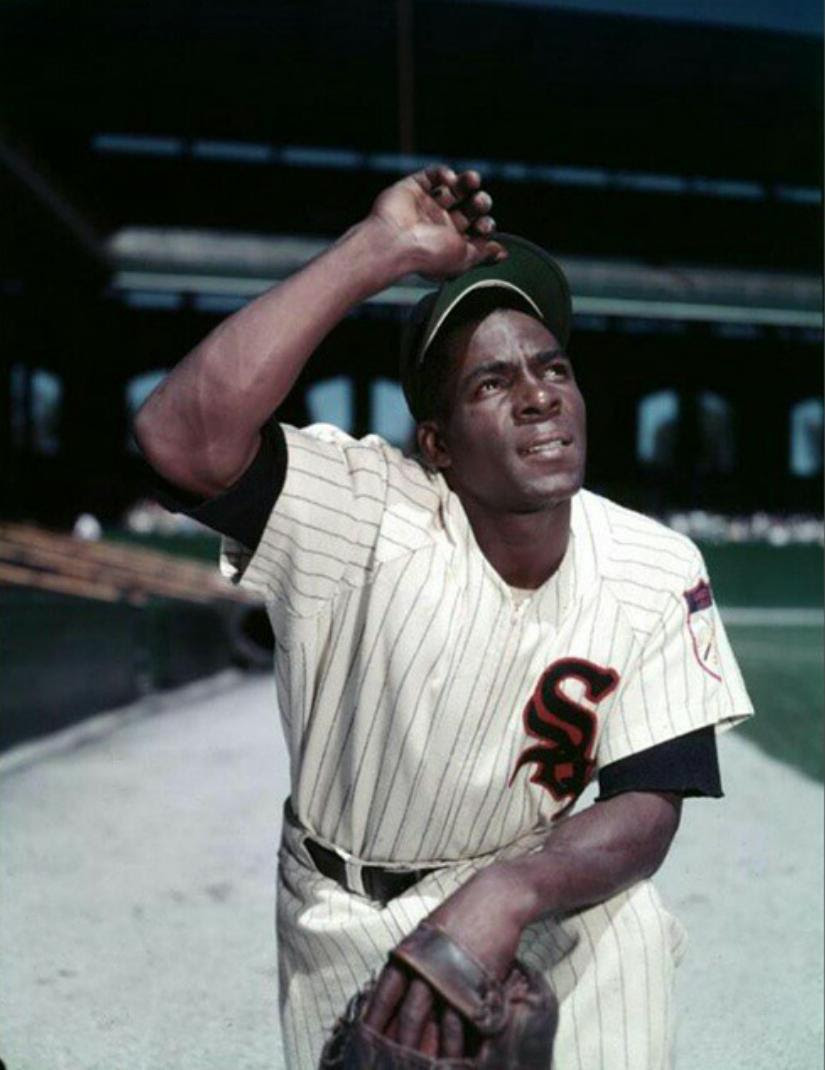

White

Sox outfielder Minnie Minoso poses outside the Comiskey Park dugout on

Sept. 3, 1960: photo by John Austad via Chicago Tribune, 1 March 2015

Minnie

Minoso, the “Cuban comet” who became Chicago’s first black major league

baseball player when he signed on with the White Sox in 1951, died

Sunday.

He was 90, according to Major League Baseball, but accounts of his age vary.

Found

unresponsive in the driver’s seat of a car at a Chicago gas station at

about 1 a.m., Minoso was declared dead at the scene, police said. Family

members believe Minoso’s death was caused by a heart ailment, his son

Charlie Rice-Minoso told the Chicago Tribune.

The son of sugar-cane cutters in Cuba, Minoso was

regarded as the first Latin American superstar, inspiring young players

from the region who dreamed of joining him in the big leagues.

Puerto

Rican native and Hall of Famer Orlando Cepeda once called him “the

Jackie Robinson for all Latinos; the first star who opened doors for all

Latin American players. He was everybody's hero. I wanted to be Minoso.

[Roberto] Clemente wanted to be Minoso.”

Minoso was a seven-time

All-Star whose combination of speed and power led a White Sox revival in

the 1950s. In his later years, he served as one of the team’s top

goodwill ambassadors.

Warm and outgoing, he decked himself out in broad-brimmed hats and colorful shirts.

“He

was adorned with gold -- on his wrists and his neck and in his teeth,”

sportswriter Marty Noble wrote in a tribute for Major League Baseball.

“He liked to flash cash and loved his green Cadillac. Minoso became

famous for being fabulous. The public adored him.”

From his first

at-bat for Chicago -- a home run against the New York Yankees -- Minoso

became an immediate star, batting over .300 eight times, with 1,023 RBIs

over 17 major league seasons.

In 1952 and 1953, he led the

American League in stolen bases. He led the league in triples in 1954

and 1956 and in doubles in 1957.

With

his tightly crouched batting stance, Minoso also made the record books

for the number of times he was hit by a pitch -- 22 in 1956 alone. For 10

seasons he led the American League. In 1955, he spent nine nights in a

hospital after a pitch fractured his skull.

Yankees

manager Casey Stengel once marveled at how fearless Minoso appeared as

hurlers aimed for the strike zone he was crowding.

“I tell my fellows to throw 'em inside there with plenty of mustard on the pitch,” Stengel said. “But that don't scare Minnie.”

Minnie Minoso at Comiskey Park on June 19, 1954: photo via Chicago Tribune, 1 March 2015

Born

Saturnino Orestes Armas Minoso Arrieta in the small Cuban town of

Perico, Minoso said in his 1994 autobiography “Just Call Me Minnie” that

his birth date was Nov. 29, 1925. Confusion arose, he said, after he

inflated his age by three years on a U.S. visa application. However, a

biography on his website gives the date as 1922, as do other sources.

At

14, Minoso played for a team run by the Ambrosia Candy Co. in Havana.

He was well known as a professional in Cuban baseball before coming to

the U.S. in 1945 and playing three seasons for the New York Cubans in

the Negro Leagues.

In 1948, Bill Veeck, then owner of the

Cleveland Indians, purchased his contract and Minoso made his major

league debut in 1949, playing nine late-season games for the Indians.

Traded to the White Sox in 1951, he hit .326 in his first season and was a runner-up for rookie of the year.

After

another few years with Cleveland in the late 1950s, he rejoined the

White Sox in 1960. Veeck by then owned the Chicago team and the two

maintained a decades-long relationship.

Famous for his

crowd-drawing gimmicks, Veeck brought Minoso out of retirement for

fleeting appearances as a player in 1976 and in 1980. In the former

outing, Minoso managed one hit in eight at bats; in the latter he went 0

for 2.

Still, Veeck scored with publicity and Minoso walked away

with bragging rights, pointing out that he was on the field for the

White Sox in five successive decades.

Minoso received some

criticism for participating in Veeck’s publicity stunts. According to

some baseball pundits, it even hurt his chances for election to

Baseball’s Hall of Fame.

In 2014, the most recent White Sox

campaign to get Minoso to Cooperstown failed, despite his .298 career

batting average, his .389 on-base percentage, and his well-known skills

in the outfield.

Bill James, a baseball statistics expert, rated Minoso the 10th-best left fielder of all time in a 2001 analysis.

“Had

he gotten the chance to play when he was 21 years old, I think he'd

probably be rated among the top thirty players of all time,” James

wrote.

In his later years, Minoso made no secret of his hope for a speedy induction.

“Don't put me in the Hall after I'm dead,” he said. “I want to taste it, like a good steak. I want to enjoy it.”

Minoso’s survivors include Sharon, his wife of 30 years; sons Orestes Jr. and Charlie; and daughters Marilyn and Cecilia.

Chisox legend Minnie Minoso, 1960. Minoso died today at 90. Another sad day for baseball.#minoso #ripminnie #HofF: image via Vintage Tribune @vintagetribune, 1 March 2015

#rip MLB's 1st black Latino star, Minnie #Minoso, has died (Getty image): image via Anne Trujillo @annnetrujillo7, 1 March 2015

What terrible, terrible news to wake up to. You will truly be missed. #RIPMinnie: image via Louie Penna @Louie_Penna, 1 March 2015 Justice, IL

Chicago loses another one of baseball's greats. R.I.P Minnie Miñoso #WhiteSox #minoso #minnieminoso: image via Louie Penna @SalOMag, 1 March 2015

Say hello to Nellie Fox for me Minnie. They were teammates 1951-1957 #RIPMinnie: image via Bob from Niles @Bob_from_Niles, 1 March 2015

Nobody looked like they were having more fun #RIPMinnie: image via Matt Rodewald @MattRodewald, 1 March 2015

Nobody looked like they were having more fun #RIPMinnie: image via Matt Rodewald @MattRodewald, 1 March 2015

Nobody looked like they were having more fun #RIPMinnie: image via Matt Rodewald @MattRodewald, 1 March 2015

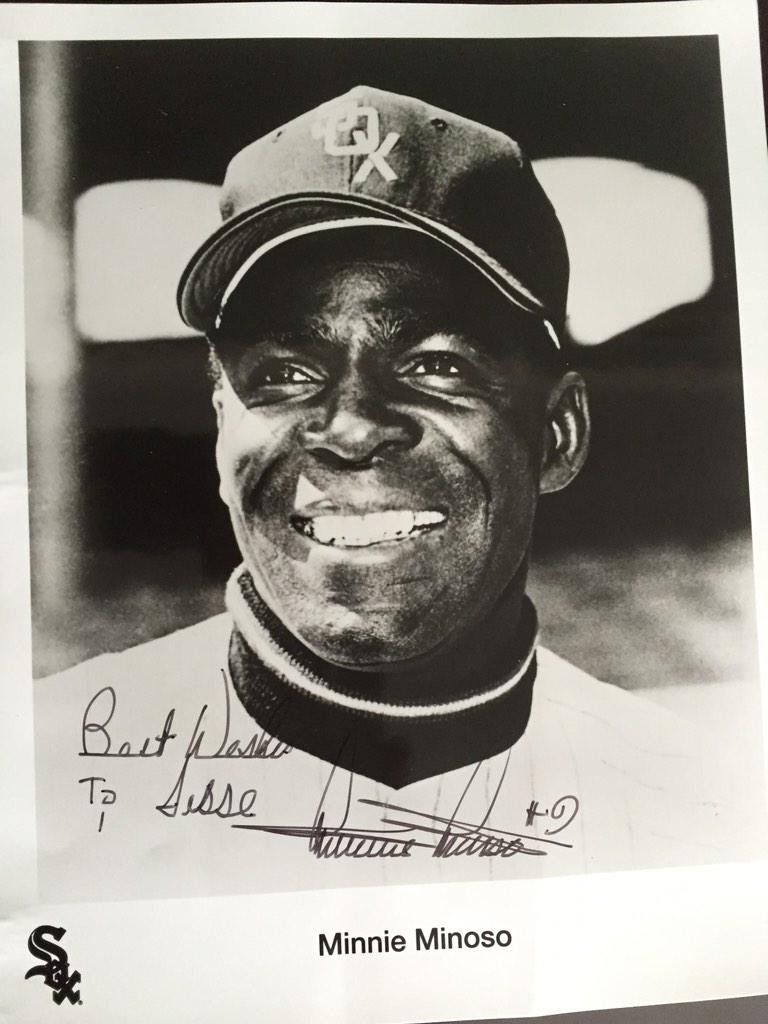

Minnie lit up and talked to us for 5-10 mins and gave me an autograph. Really made my day as a kid. #RIPMinnie: image via jesse @WhiteCrow12, 1 March 2015

Miñoso was an instrumental piece of the Go-Go Sox: photo by AP via The Guardian, 1 March 2015

White Sox players of Latin descent (left to right) Mike Fornieles, Chico Carrasquel, Minnie Minoso and Jim Rivera, pose for a photo at Comiskey Park in 1955: photo via Chicago Tribune, 1 March 2015

Minnie Minoso is greeted by fans as the team arrived at LaSalle St. Station on May 28, 1951: photo via Chicago Tribune, 1 March 2015

White

Sox great Minnie Minoso, 82, visits the mural that features him

prominently as the largest figure (see player directly behind him) in a

series of African American ballplayers that was unveiled on 35th Street

below the Metra tracks at Federal: photo by Nancy Stone via Chicago Tribune, 1 March 2015

The White Sox's Minnie Minoso slides into third for a triple in a 12-1 route of the Cleveland Indians on May 12, 1951: photo via Chicago Tribune, 1 March 2015

Safely home. RIP Minnie #CubanComet #Minoso: image via MOReilly @oreillys708, 1 March 2015

nice tribute !

ReplyDeleteWhat a wonderful tribute to Minnie Minoso... who should have been voted into the Baseball Hall of Fame decades ago.

ReplyDeleteThank you for showing us that Minnie certainly weren't no mouse--too bad the Hall of Fame selection team was infested by rats.

ReplyDeleteOf course, who knew what was going on inside Minnie. Getting hit by pitches 16 times a year merely means they were trying to hit you three or four times that often, but missed. He had a great eye and was famous for his sense of the strike zone, almost unerring -- you could look it up like they say. He walked something like 800 times in his career, struck out only a quarter or so of that number, very rare for a hitter, let alone a ferocious hitter like Minnie. But what am I saying. He was a force.

ReplyDeleteA few years back the so called Golden Era selection committee, whose privilege it is to resuscitate forgotten heroes by belatedly admitting them to the Hall, considered Minnie's case once again; the opportunity for this sort of late admission comes every three years; toward the end of this past year the committee adjudicated again, Minnie was again passed over. He was disappointed. Bitter almost, maybe. A few months after that he was dead