#MyLai: @Seymour Hersh habla de la masacre que EEUU perpetró en 1968 y que él mismo denunció: image via Democracy Now! Es @DemocracyNowEs, 25 March 2015

Seymour Hersh: My Lai Revisited: excerpts from transcription of an interview, via Democracy Now!, 25 March 2015

If you remember, Richard Nixon came to

office, defeated Humphrey in 1968. Humphrey would not go against the

war, Lyndon Johnson’s war, his president’s war. He was the vice

president. Nixon won by claiming he had a secret plan to end the war.

And by the middle of 1969, or late 1969, it was clear his secret plan

was to win it — not end it, but win it. And so, antiwar feelings were

getting high. And I got a tip from — there were a lot of desertions, a lot

of trouble inside the Army. Also, there were hearings and

investigations, particularly one particular hearing in Detroit,

Michigan, where a group of GIs, even a year earlier, 1968, had gone

public with story after story of horrific incidents taking place. And I

had read all those things. I was — you know, I guess I believe you can’t

really write if you don’t read. And I knew how much there was an

underbelly of very ugly stuff in that war that wasn’t being reported.

And so, when I got a tip in 1969, late 1969, I

was a freelance writer. I had worked for the Associated Press, etc. And

I had learned — I had covered the Pentagon for a few years and learned

sort of OJT on how the war was being driven.

Promotions in the war by 1966 and '67 were being driven by body

count — how many could you kill? And inevitably, the officers and

soldiers, eager to get more deaths, more killings, would stop

differentiating in many areas, particularly the areas in Vietnam where

My Lai took place — Quang Ngai, Quang Tri, Quang Nam — sort of areas known

to be heavily engaged and committed to opposition to the South

Vietnamese government. We called them Viet Cong. They weren't

really — many of them were not communist, per se; they were nationalists against the war. But nonetheless, we carried the war — we were carrying the war very hard to them.

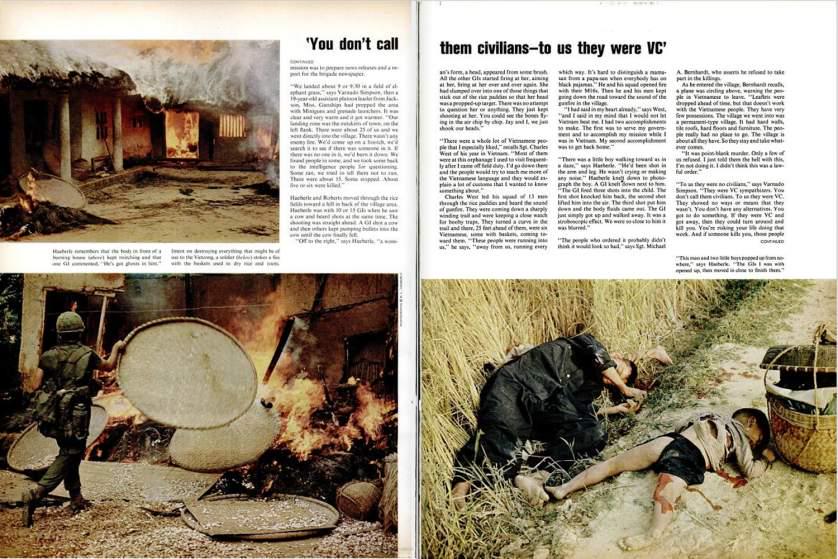

Unidentified bodies near burning house. My Lai, Vietnam, March 16, 1968: photo by Sgt Ronald L. Ronald Haeberle, from Department of the Army Review of the Preliminary Investigations in the My Lai Incident; image by bcs78, 31 December 2006

So I knew all that. So when I got a tip from a

lawyer, named Geoffrey Cowan, at the time, he was just involved in

antiwar issues, working in Washington, that he had heard something about

a massacre, I went looking. And there’s — you know, I was a soldier, I

was in the Army, and I covered the Pentagon. And there is an enormous

streak of decency and goodwill among many officers. And I’ve always — I

always say this about the American intelligence community, too. Don’t

write them off. There’s a lot of people with a lot of high integrity.

And there was one day — I got nowhere on this story. And one day I was in

the Pentagon, rolling around, I guess; I was going through the legal

offices. The fact that officers had been detained by the Army on the

suspicion of mass murder was not part of the record. I actually had run

across Lieutenant Calley’s name, but I was told he was a — he had shot up a

bunch of prostitutes in a bar in Saigon or something like that. Whoever

told me that, that’s what he believed, that’s what he was told. But it

wasn’t true. I didn’t know that.

And anyway, I ran into a colonel I knew, I had

known when I was in the Pentagon earlier, who had just been promoted to

general. And he was limping. He had been shot in the war. And I just

started talking with him about it, teased him a little bit about taking a

bullet to make general. You know, the black humor always is very big in

the military. And then I said, "What’s this about some guy shooting up a

lot of people?" And the colonel, soon to be a general, slammed his hand

against his wounded knee, the knee in which he had a bullet while in

Vietnam, and he said to me, "Oh, Hersh," he said, "that guy Calley

didn’t shoot anybody higher than that." And at that moment, at that

moment, I knew I had a story, that there was something there, something

big. So I just kept on going.

I eventually found the name of Lieutenant

Calley’s lawyer. I eventually got to the lawyer. I eventually got to

Calley. And it was interesting, because I had heard so much about

Calley. And I had actually seen by then a charge sheet accusing him. The

Pentagon had initially accused him of something like 109 or 111, the

killing of — get this — Oriental human beings. That was the initial charge

sheet, as if 10 whites equaled one Oriental, or 12 blacks equaled one — I

wasn’t sure what the number was. But believe me, they got rid of that as

soon as I went public with that word. They took it out of the charge.

It was a very interesting sort of notion, the notion of racism that’s so

dominant in that war, as it is in all wars, I guess. You have to

dehumanize the other person.

#OTD March 16 - 1968 #VietnamWar 450 @Men #Women and #Children die in the #MyLai #Massacre: image via Gerald McDonald @NovaRoma1, 16 March 2015

At the time of the massacre, this was going to

be a big operation, and everybody thought, boy, we’re going to

get — there was very bad intelligence. The intelligence was a Viet Cong

battalion was there, the 48th, I think, and our boys were going to go in

and kill them, and there was going to be a big ambush. And, of course,

when we went in, there was nothing but women and children. The

intelligence was lousy, as it always was. And they murdered everybody.

They had been told to kill everybody you see. God knows what the real

reality was, whether that was actually what — what happened, they went out

of control, as they had many times before.

But, what I learned was that this was the big

deal for the whole division. Charlie Company was attached to a task

force, that was attached to a battalion, that was attached to a

division. You know, we’re talking about 20,000 men, led by a major

general named Koster. And that day, Koster, his deputy, another general

named Young, a colonel who was in charge of the regiment to which the

task force was attached, a battalion — colonels, generals, lieutenant

colonels, majors were flying above, and I can just tell you from what I

know, you had to understand, when you saw that village, with pits full

of bodies, you knew there was something horrible that happened. They all

knew it. They all covered it up. Actually, what they did is they

reported to headquarters that that day had produced a great victory,

that they had killed 128 Viet Cong with only three weapons captured — I

mean, which was a flag in itself.

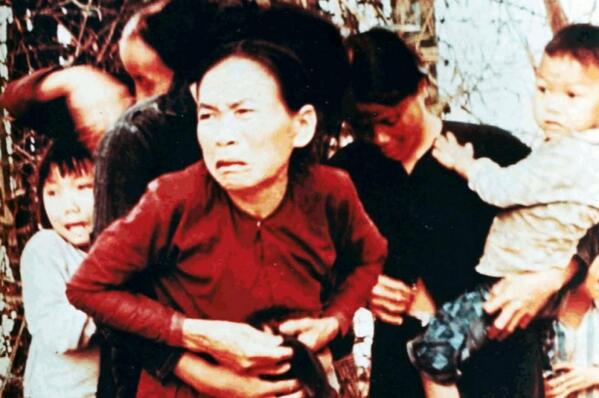

For Decades, the Media Have Ignored the #Rapes Behind a Famous Vietnam War Photo #myLai: image via Winter Thur @winterthur, 31 October 2013

They went in in the morning, a group of boys — and you’ve got

to give them credit. You know, they toked the night before, and they

did their whiskey the night before. They had their — you know, their

drugs. But that morning, they got up thinking they were going to be in

combat against the Viet Cong. They were happy to do it. Charlie Company

had lost 20 people through snipers, etc. They wanted payback. And they

had been taking it out on the people, but they had never seen the enemy.

They’d been in country, as I said, in Vietnam for three or four months

without ever having a set piece war. That’s just the way it is in

guerrilla warfare — which is why we shouldn’t do it, but that’s another

story. And they went in that morning ready to kill and be killed on

behalf of America, to their credit. They landed. There were just nothing

but women and children doing the usual, cooking, warming up rice for breakfast — and they began to put them

in ditches and start executing them.

Calley’s company — Calley had a platoon. There

were three platoons that went in. They rounded up people and put them in

a ditch. And Meadlo was ordered by Calley. He was among one or two or

three boys who did a lot of shooting. There was a big distinction,

basically, between the white boys, country boys like Paul Meadlo who did

the shooting, and the African Americans and Hispanics, who made up

about 40 percent of the company. In my interviews, I found that

distinction. Most of the African Americans and Hispanics, that was

Whitey’s war. The whole thing was Whitey’s war for them. And they did

shoot, because they were afraid that their white colleagues might shoot

at them if they weren’t participating, but they shot high. One guy even

shot himself in the foot to get out of there. I mean, we had that going

on, too, above and beyond the normal stuff.

The other companies just went along, didn’t

gather people, just went from house to house and killed and raped and

mutilated, and had just went on until everybody was either run away or

killed. Four hundred and some-odd people in that village alone, of the

500 or 600 people who lived there, were murdered that day, all by noon,

1:00.

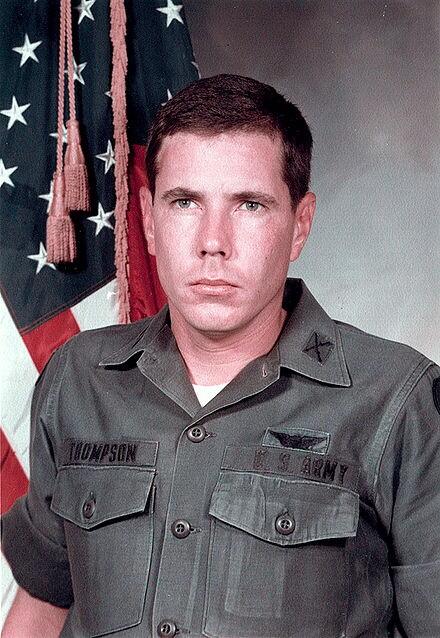

On 1 of the darkest days in US history, Hugh Thompson, Jr was a hero. He would've been 71 today. #myLai: image via Brent Scales @Boiler40, 15 April 2014

At one point, one helicopter pilot, a wonderful man named

Thompson, saw what was going on and actually landed his helicopter. He

was a small combat — had two gunners. He just landed his small helicopter,

and he ordered his gunners to train their weapons on Lieutenant Calley

and other Americans. And Calley was in the process of — apparently going

to throw hand grenades into a ditch where there were 10 or so Vietnamese

civilians. And he put his guns on Calley and took the civilians, made a

couple trips and took them out, flew them out to safety. He, of course,

was immediately in trouble for doing that.

It was just the instinct to not do the right

thing. You know, the thing that you discovered about Vietnam was, there

was no such thing as a war crime. It just didn’t exist. The idea of a

war crime didn’t exist. There were violations of rules and things you

did wrong. And one of things that emerged in Vietnam — a defense to, let’s

say, rape — would have been what they called the MGR,

the Mere Gook Rule: It was just a gook. I’m not exaggerating. It was

that terrible, that racist. You talk about number of deaths in Iraq, and

the number is staggering, but we usually talk in Vietnam — we don’t get

within — we talk — is it one or two or three million civilians and innocents

killed between the North and the South?

Photo: Guerre du Vietnam, le Massacre de My Lai #myLai #vietnam #guerreduvietnam: image via Forum Vietnam @ForumVietnam, 25 March 2015

[Paul Meadlo] and another soldier from Texas had been asked by Calley — they had no

idea what Calley’s intent was. Paul Meadlo was a kid. You know, he had

been married young. He was from New Goshen, Indiana, from a farm family.

His father worked in the mines on the border with Illinois. And they

were very close to the border in New Goshen, near Terre Haute. He was a

farm kid, into the Army, trained to be a killer. His brother told me

when I was doing interviews for this piece — I talked to his brother,

Larry, who lives near him, and said Paul was the — he couldn’t skin an

animal after shooting them when hunting. He didn’t like the sight of

blood. The last person that should have been drafted, but he was

drafted, and he went.

And that morning, Calley ordered Meadlo and

others to collect a group of women and children. They had 40 or 50,

perhaps more, some old men, mostly women and kids. And Paul and the

other guys, Calley said to watch them. And so they did what kids,

American guys, will do: They passed out candy. They were horsing around

with the kids, playing with the kids. They told the people where to sit.

And Calley came back and said, you know, in effect, "What are you

doing?" He said, "I told you to take care of them." He said, "Well, I

am." He said, "No, I want them killed."

La companie #US #CHARLIE a massacré #MYLAI au #Vietnam le 16 mars 1968! #USA #URSS #Russie: image via Claire - Normans @Slava_Russia72, 1 March 2015

And then Meadlo began following orders. He

began crying. This is something I did not know until I revisited some of

the investigations. I went and reread everything that the Army had

done. I just had not read it all before. And I found other witnesses who

testified at Army hearings. After my stories came out, there was a big

investigation by a general named Peers. And there was another soldier, a

New York kid. Naturally, a New York street kid wasn’t going to shoot,

but he watched what happened. He testified about Meadlo beginning to

cry. He didn’t want to do it, and Calley ordered him to. And he began to

shoot and shoot. And they fired clips — I don’t know how many clips; he

told me at one point five or six; he testified later about one, but he

told me four, maybe five, clips — a clip in that rifle, an M1, has 17

bullets — into it, into the ditch.

And there was a horrible moment that got me,

really got me. At some point, when they were done shooting, some mother

had protected a baby underneath her body in the bottom of the ditch. And

the GIs heard, as somebody said to me, a keening, a crying, whimpering

noise, and a little two- or three-year-old boy crawled his way out full

of other people’s blood from the ditch. It’s hard for me to talk about

this. And right across what was — it’s now been plowed over, but it was a

rice ditch. It’s now been paved over at the site. And I saw it all. I’d

seen it in my mind, and I saw it visually that day I was there. And the

kid was running away, and Calley went after it — Calley, big, tough guy

with his rifle — and dragged him, grabbed him, dragged him back into the

ditch and shot him. And that stuck in people’s minds.

#Taldíacomohoy de 1970, #EEUU, Guerra #Vietnam, teniente William Calley va a juicio por ordenar la masacre de #MyLai: image via Red Communismor @RedCommunismo, 17 November 2014

That’s how I got to Calley. It was a repressed

memory, what happened at that ditch. And as I was doing my interviews

early in the story — I had written two stories for Dispatch. And the

press, I will tell you, the American press, was — they were open to the

story. They didn’t really get into it. They let me sort of run with it

for weeks. It made me think, as I still do, that you can really do stuff

if you want to do stuff. The American press, they may not be

aggressive, but if you do stuff that they think is right, they will

publish it. I’d like to think that’s still true. I mean, it happened in

Abu Ghraib, and it happened in other stories I’ve written. There’s a lot

of resistance to stories sometimes, but not in this case. It just

seemed right. And anyway, soldiers had told me — finally, they told me

about Paul Meadlo. And as I wrote in the piece, I was in Salt Lake City

at the time I heard about him and what he did and what happened. I

didn’t hear about crying, but I heard about his resistance and about the

little boy. And I spent hours on a payphone. His name was M-E-A-D-L-O,

and I knew he lived in Indiana. I called every major phone district,

city, and got the chief operator and asked for Meadlo, finally found

him.

And I asked — I got the house, and I called the

house in New Goshen. And I asked — I knew he had had his — the next day,

Paul Meadlo had had his leg blown off by stepping on a mine. And he kept

on saying — as he was waiting for the helicopter to take him to a

hospital, he kept on yelling at Calley, "God is punishing me! And God

will get you, B! God will get you for this!" And they finally took him

away. So, when I called his home, and I would ask — I got this woman, this

old Southern voice, and I said, "Is Paul there?" And she said, "Yes,"

which was great. And I said, "How is his leg?" She says, "Well, you

know, I don’t know." And I asked if I could see him. She said, "Yes. Ask

him." She didn’t know. She didn’t know much about what happened. She

knew something bad had happened. And I flew down there.

And I went — it took me a long time to get to New Goshen, Indiana. No GPS

then. I mean, I flew across country all night, but I got there by

afternoon to this little rinkety-dinkety farm full of — a farm with no man

around, full of chickens, that were — chicken coops that were broken

down. But she came out to meet me. And this is one of those moments you

live for as a journalist, I guess. This woman, who really wasn’t really

in the world, didn’t know much about what was going on. Paul hadn’t told

her much. She came out to meet me, and I pulled in 3:00 or 4:00 in the

afternoon. And I said, "I’m the" — I told her I was a reporter, and I

said, "I’ve come to see Paul. Is he in?" She said, "He’s in there." She

said, "I don’t know if he’ll talk to you, but he’s in there. He knows

you’re coming." And then she said to me, this old woman, she said, in

this tone of a voice, "I gave them a good boy, and they sent me back a

murderer." And you can go a long time in this business without having a

line like that played in your head.

#MyLai one of many examples of the "#freedom and #democracy" our NATO EU régimes, South Korea, Taiwan, Saigon love: image via @VivaSAA Rafiq @Rafiq_al_Taneen, 29 April 2014

Sy Hersh tells the story of how he found William Calley

ReplyDeleteMy Lai Massacre, March 16, 1968

ReplyDeletehttp://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/My_Lai_Massacre

That My Lai is the story that got out, that there were countless other atrocities, that's the horror that sticks.

ReplyDeleteDidn't Colin Powell have something to do with the cover up?

Duncan,

ReplyDeleteBy Hersh's account -- and he was and is an extremely thorough investigative reporter -- the coverup of My Lai went through the whole command structure, up to and including Powell.

Many corroborative sources, here.

This via Consortium News:

By late 1968, Powell had jumped over more senior officers into the important post of G-3, chief of operations for division commander, Maj. Gen. Charles Gettys, at Chu Lai. Powell had been "picked by Gen. Gettys over several lieutenant colonels for the G-3 job itself, making me the only major filling that role in Vietnam," Powell wrote in his memoirs.

But a test soon confronted Maj. Powell. A letter had been written by a young specialist fourth class named Tom Glen, who had served in an Americal mortar platoon and was nearing the end of his Army tour. In a letter to Gen. Creighton Abrams, the commander of all U.S. forces in Vietnam, Glen accused the Americal division of routine brutality against civilians. Glen's letter was forwarded to the Americal headquarters at Chu Lai where it landed on Maj. Powell's desk.

"The average GI's attitude toward and treatment of the Vietnamese people all too often is a complete denial of all our country is attempting to accomplish in the realm of human relations," Glen wrote. "Far beyond merely dismissing the Vietnamese as 'slopes' or 'gooks,' in both deed and thought, too many American soldiers seem to discount their very humanity; and with this attitude inflict upon the Vietnamese citizenry humiliations, both psychological and physical, that can have only a debilitating effect upon efforts to unify the people in loyalty to the Saigon government, particularly when such acts are carried out at unit levels and thereby acquire the aspect of sanctioned policy."

Glen's letter contended that many Vietnamese were fleeing from Americans who "for mere pleasure, fire indiscriminately into Vietnamese homes and without provocation or justification shoot at the people themselves." Gratuitous cruelty was also being inflicted on Viet Cong suspects, Glen reported.

"Fired with an emotionalism that belies unconscionable hatred, and armed with a vocabulary consisting of 'You VC,' soldiers commonly 'interrogate' by means of torture that has been presented as the particular habit of the enemy. Severe beatings and torture at knife point are usual means of questioning captives or of convincing a suspect that he is, indeed, a Viet Cong...

"It would indeed be terrible to find it necessary to believe that an American soldier that harbors such racial intolerance and disregard for justice and human feeling is a prototype of all American national character; yet the frequency of such soldiers lends credulity to such beliefs. ... What has been outlined here I have seen not only in my own unit, but also in others we have worked with, and I fear it is universal. If this is indeed the case, it is a problem which cannot be overlooked, but can through a more firm implementation of the codes of MACV (Military Assistance Command Vietnam) and the Geneva Conventions, perhaps be eradicated."

Glen's letter echoed some of the complaints voiced by early advisers, such as Col. John Paul Vann, who protested the self-defeating strategy of treating Vietnamese civilians as the enemy. In 1995, when we questioned Glen about his letter, he said he had heard second-hand about the My Lai massacre, though he did not mention it specifically. The massacre was just one part of the abusive pattern that had become routine in the division, he said.

[Consortium News report continues:]

ReplyDeletePowell's Response

The letter's troubling allegations were not well received at Americal headquarters. Maj. Powell undertook the assignment to review Glen's letter, but did so without questioning Glen or assigning anyone else to talk with him. Powell simply accepted a claim from Glen's superior officer that Glen was not close enough to the front lines to know what he was writing about, an assertion Glen denies.

After that cursory investigation, Powell drafted a response on Dec. 13, 1968. He admitted to no pattern of wrongdoing. Powell claimed that U.S. soldiers in Vietnam were taught to treat Vietnamese courteously and respectfully. The Americal troops also had gone through an hour-long course on how to treat prisoners of war under the Geneva Conventions, Powell noted.

"There may be isolated cases of mistreatment of civilians and POWs," Powell wrote in 1968. But "this by no means reflects the general attitude throughout the Division." Indeed, Powell's memo faulted Glen for not complaining earlier and for failing to be more specific in his letter.

Powell reported back exactly what his superiors wanted to hear. "In direct refutation of this [Glen's] portrayal," Powell concluded, "is the fact that relations between Americal soldiers and the Vietnamese people are excellent."

Powell's findings, of course, were false. But it would take another Americal hero, an infantryman named Ron Ridenhour, to piece together the truth about the atrocity at My Lai. After returning to the United States, Ridenhour interviewed Americal comrades who had participated in the massacre.

On his own, Ridenhour compiled this shocking information into a report and forwarded it to the Army inspector general. The IG's office conducted an aggressive official investigation and the Army finally faced the horrible truth. Courts martial were held against officers and enlisted men implicated in the murder of the My Lai civilians.

__

Ronald Ridenhour would prove a key informant for Hersh, providing him with names.

Hersh: I went from Calley — I wrote a story about Calley, and then I went and began to find people, kids who were involved, with the help of a wonderful soldier named Ronald Ridenhour, who’s now passed away, but Ridenhour was one of the few people who knew about My Lai and tried to do something about it.

__

As to the similar atrocities occurring in the same period: Hersh insists the My Lai incident was not isolated, but typical.

Here again, another excerpt from this week's interview:

Hersh: It was hard to see the ditch. It was hard to see how so many American boys could do so much and how it could be so thoroughly covered up by the government, not only up until the time I wrote about it, but even afterwards. There were investigations that couldn’t cope with the reality, which is — one of the realities is, one of the massacres was, even on that day, the same unit, the same — it was a task force with three companies, Charlie Company, led by the infamous William Calley, who of course was one of six or seven officers on the ground, but he was the fall guy. They did the killing in My Lai. But less than a mile or two, maybe a mile and a half, away was another village called My Khe, where the same task force with a different company went in and executed 97 people. So, the Army, when it began to look seriously into what I had written about, discovered the second massacre, in their own interviewing, and, of course, just couldn’t cope with it. They simply buried that fact. So, My Lai, yes, it was terrible. It was much worse than other incidents. But incidents killing 60, 100, 120, there was just much too much of that during the war. Really bad leadership.

Tom, this is-in a strange way-compelling reading, but, but...

ReplyDelete"And there is an enormous streak of decency and goodwill among many officers. And I’ve always — I always say this about the American intelligence community, too. Don’t write them off. There’s a lot of people with a lot of high integrity."

Really? Seriously?

I don't know, was reading Yellow Birds (a half decent book) and it's always there: it's not *really* us..we can't be the bad guys. Rotten apples and all that.

By the by, one of the few sensitive early reports on the enormity of the My Lai atrocity, and its context, came in Frances Fitzgerald's great 1972 book, Fire in the Lake: The Vietnamese and the Americans in Vietnam.

ReplyDeleteFitzgerald:

[At My Lai] a photographer had taken pictures of screaming women, dead babies, and a mass of bodies piled up in a ditch. How could American soldiers have committed such an atrocity?... [But] the incident was not exceptional in the American war.

Young men from the small towns of America, the GIs who came to Vietnam found themselves in a place halfway round the earth among people with whom they could make no human contact. Like an Orwellian army, they knew everything about military tactics, but nothing about where they were or who the enemy was. And they found themselves not attacking fixed positions but walking through the jungle or through villages among small yellow people, as strange and exposed among them as if they were Martians. Their buddies were killed by land mines, sniper fire and mortar attacks, but the enemy remained invisible, not only in the jungle, but among the people of the villages -- an almost metaphysical enemy who inflicted upon them heat, boredom, terror and death, and gave them nothing to show for it -- no territory taken, no visible sign of progress except the bodies of small yellow men. And they passed around stories: you couldn't trust anyone in this country, not the laundresses or the prostitute or the boys of six years old. The enemy would not stand up and fight, but he had agents everywhere, among the villagers, even among the ARVN officers. The Vietnamese soldiers were lazy and the officials corrupt -- they were all out to get you one way or another. They were all "gooks", after all. Just look how they lived in the shacks and the filth: they'd steal the watch off your arm.

And the stories of combat were embellished...

Billoo, sorry, hadn't seen your comment till a moment ago.

ReplyDeleteYes, this statement of Hersh's bothered me too.

"And there is an enormous streak of decency and goodwill among many officers. And I’ve always — I always say this about the American intelligence community, too. Don’t write them off. There’s a lot of people with a lot of high integrity."

I considered editing it out -- after all, I've already edited he Hersh interview extensively, here, because it wanders off at some points -- but decided that would be neither fair nor honest.

In fact I heard the interview "live", also.

My sense of the thing is that Hersh, as a veteran, not only a military veteran from way back when, but by now a veteran investigative reporter, is speaking honestly when he says there were men of decency and goodwill, a minority certainly, but still -- but, at the same time, that there are several factors to be considered when looking at such a statement.

The most important by far is the inarguable truth that Hersh's style of reporting, dogged, persistent, tireless and almost entirely dependent upon gaining the trust of those who could and very often did lead him closer to the heart of the matter, has been reliant all along on his sources.

And he would clearly intend to keep it that way.

Does this make him complicit?

Each of us must be her/his own judge, on that. Not forgetting that with Hersh, and his style of reporting, there are truths about American military conduct in Vietnam, and Iraq, and Afghanistan, that may never have seen the light, or at any rate would certainly have taken longer to be brought out into it.

In the earlier tv interview to which I linked at the top of these comments, Hersh makes a statement to the effect that the burden of pain was in the long run perhaps greater for the My Lai perpetrators than for their victims.

My partner here scoffed at that.

I would do likewise... were it not for the understanding that Hersh followed those perpetrators closely in later years, and saw what they had become -- moral husks, cripples, drug and alcohol abusers, loners hiding out from a past for which they could no longer rationally account.

Not in any case that they'd been able to rationally account, at the time, or ever, for the things they had done in that war.

As far as I'm concerned, personally, it tore America apart, forever, and only the broken pieces remain, to go on conducting the neverending wars.

Since late 1965, and the Battle of the Ia Drang Valley, in which several of my school classmates died in close combat with a surprisingly efficient force of NVA regulars, and after which no more believable lies could ever be maintained as to the depth and seriousness and meaning of this conflict for America, and yet the conflict was nonetheless pursued with greater and greater fury on the part of the war criminals on high, I've felt very much like someone without a country, apart from it, whether outside or in it -- and this has had consequences.

So I can't take any of the matters touched on here lightly.

Tom,

ReplyDeleteI have no doubt whatsoever about Hersh's integrity or the incredible work he has produced (the little I've read of it).

And of course it's worth remembering-trying to remember-that many people (kids) are duped or suckered into violent acts for king and country. And I'm sure a lot of them suffer in one way or another (guilt, remorse, psychological distress). I'm not saying that one can or should ignore that. But-as in Yellow Birds- our sympathies are supposed to be for the *perpetrators* of violence. In a strange twist, they become the victims! and we're all supposed to show our humanity by thinking of their sorrow. Fine. But not if it detracts from the real horror and not if it means that the latter gets written out of the story.

Just my tuppence worth.

"I gave them a good boy, and they sent me back a murderer."--a bullet straight into the heart of America.

ReplyDeleteAnd that bullet is still turning in the wound.

ReplyDeleteAnd Billoo, as to your latest -- couldn't agree more. The nobility of the dead, in our historical memories, doesn't do them much good. The ignoble yet real sufferings of the perpetrators -- presumably guilt and remorse will eventually bore their way even through the thickest hide -- can't bear comparison.

(Calley, making a rare public appearance at a veterans' event near Fort Benning a few years back, claimed to bhave been haunted by his crimes, every day, for nearly half a century now.)

Hersh covered the war from America, not from Vietnam. He had later visited the North. His first visit to My Lai came only recently.

During his long investigations he had become personally familiar with the perpetrators, but was reduced, perforce, to a much less intimate sort of contact with the victims.

This changed when he went back to Vietnam, on assignment for The New Yorker.

Quoting now from his New Yorker piece:

I visited My Lai (as the hamlet was called by the U.S. Army) for the first time a few months ago, with my family. Returning to the scene of the crime is the stuff of cliché for reporters of a certain age, but I could not resist. I had sought permission from the South Vietnamese government in early 1970, but by then the Pentagon’s internal investigation was under way and the area was closed to outsiders. I joined the Times in 1972 and visited Hanoi, in North Vietnam. In 1980, five years after the fall of Saigon, I travelled again to Vietnam to conduct interviews for a book and to do more reporting for the Times. I thought I knew all, or most, of what there was to learn about the massacre. Of course, I was wrong.

My Lai is in central Vietnam, not far from Highway 1, the road that connects Hanoi and Ho Chi Minh City, as Saigon is now known. Pham Thanh Cong, the director of the My Lai Museum, is a survivor of the massacre. When we first met, Cong, a stern, stocky man in his late fifties, said little about his personal experiences and stuck to stilted, familiar phrases. He described the Vietnamese as “a welcoming people,” and he avoided any note of accusation. “We forgive, but we do not forget,” he said. Later, as we sat on a bench outside the small museum, he described the massacre, as he remembered it. At the time, Cong was eleven years old. When American helicopters landed in the village, he said, he and his mother and four siblings huddled in a primitive bunker inside their thatch-roofed home. American soldiers ordered them out of the bunker and then pushed them back in, throwing a hand grenade in after them and firing their M-16s. Cong was wounded in three places—on his scalp, on the right side of his torso, and in the leg. He passed out. When he awoke, he found himself in a heap of corpses: his mother, his three sisters, and his six-year-old brother. The American soldiers must have assumed that Cong was dead, too. In the afternoon, when the American helicopters left, his father and a few other surviving villagers, who had come to bury the dead, found him.

[Hersh, TNY, continues:]

ReplyDeleteLater, at lunch with my family and me, Cong said, “I will never forget the pain.” And in his job he can never leave it behind. Cong told me that a few years earlier a veteran named Kenneth Schiel, who had been at My Lai, had visited the museum — the only member of Charlie Company at that point to have done so — as a participant in an Al Jazeera television documentary marking the fortieth anniversary of the massacre. Schiel had enlisted in the Army after graduation from high school, in Swartz Creek, Michigan, a small town near Flint, and, after the subsequent investigations, he was charged with killing nine villagers. (The charges were dismissed.)

The documentary featured a conversation with Cong, who had been told that Schiel was a Vietnam veteran, but not that he had been at My Lai. In the video, Schiel tells an interviewer, “Did I shoot? I’ll say that I shot until I realized what was wrong. I’m not going to say whether I shot villagers or not.” He was even less forthcoming in a conversation with Cong, after it became clear that he had participated in the massacre. Schiel says repeatedly that he wants to “apologize to the people of My Lai,” but he refuses to go further. “I ask myself all the time why did this happen. I don’t know.”

Cong demands, “How did you feel when you shot into civilians and killed? Was it hard for you?” Schiel says that he wasn’t among the soldiers who were shooting groups of civilians. Cong responds, “So maybe you came to my house and killed my relatives.”

A transcript on file at the museum contains the rest of the conversation. Schiel says, “The only thing I can do now is just apologize for it.” Cong, who sounds increasingly distressed, continues to ask Schiel to talk openly about his crimes, and Schiel keeps saying, “Sorry, sorry.” When Cong asks Schiel whether he was able to eat a meal upon returning to his base, Schiel begins to cry. “Please don’t ask me any more questions,” he says. “I cannot stay calm.” Then Schiel asks Cong if he can join a ceremony commemorating the anniversary of the massacre.

Cong rebuffs him. “It would be too shameful,” he says, adding, “The local people will be very angry if they realize that you were the person who took part in the massacre.”

Before leaving the museum, I asked Cong why he had been so unyielding with Schiel. His face hardened. He said that he had no interest in easing the pain of a My Lai veteran who refused to own up fully to what he had done. Cong’s father, who worked for the Vietcong, lived with Cong after the massacre, but he was killed in action, in 1970, by an American combat unit. Cong went to live with relatives in a nearby village, helping them raise cattle. Finally, after the war, he was able to return to school.

Thanks for that, Tom. Cong's response reminded me a bit of Primo Levi's response to a German (doctor?): don't give an inch, don't shift the balance..

ReplyDeleteI dunno, maybe it's just that the personal stories of people just like us (people we went to school with, ordinary folks) is something we can relate to more easily. And so the media will pick up that side (like Deer Hunter which still remains a brilliant film today).

Hmm, Cong and Primo.

ReplyDeleteCong, possibly made of tougher stuff, wouldn't have jumped down the stairwell, for one.

(But of course neither would Primo, as it turns out.)

Well, in any case, that "just like us" can be somewhat complicated.

The Deer Hunter, powerful American fantasy mythology -- just like us indigenous-to-the-Steel Belt Hollywood actors deerhunting in the snow-peaked Ukrainian-American Cascades of the Allegheny Valley.

In reference to a person like Cong, really, beyond the intelligible nationalism, Just like us can only mean something larger -- people like those who have sustained extraordinary suffering over a great duration, and endured, and survived.

A "just like us" in regard to ordinary US folks, has, alas, always been a bit beyond my capacity, shameful to admit.

But it's hard not to be thinking on through the rheumy eyed night about all this history -- in effect the story of one's life.

The person now trying to sleep in the next room, not an American by the way, and I, now keeping her awake, were wed the same week My Lai happened.

Not that we knew of it.

We were on the run from it.

A cross-country car-crash-interrupted fugitive trek later, at the airport in Colorado Springs, a transit point for the wartime military, we saw thousands of terrified youth, in crisp new uniforms, with fear, not triumph, in their eyes, preparing to be flown off to battle.

The whole deal had come apart by then. The war would go on another five years. Five years of nothing but bad. And not even ending then. The bad done by Kissinger still blows up in the faces of children and rice farmers in Laos, every day, now, in the New Millennium.

Hearing Hersh talk about his long investigation, it's plain there were signal moments, when a hint or a clue would drive him on to renewed beavering and burrowing in pursuit of the story.

This is old time journalism at its best, driven, but tight.

Still the energy has to come from somewhere.

Hearing Hersh's account of his work on this story, it's plain certain moments were key.

The moment to which Vassilis points.

And prior to that of course, Hersh's instinctive grasp of the historical depth of the story seems to spring up almost like tears from a stone, with learning of Paul Meadlo's tears.

It's hard to conjure from this distance the dimensions of the burning lake of tears, of those years.

There were a number of terrific writers to come out of the Vietnam ordeal.

One of a different sort, less reporter than writer, was Michael Herr.

Herr also saw the war turning on certain key moments, slipping into that well of confusion and tears, in this bit concerning the unhappy American experience at Dak To: the tears of the woman in the brief text, and the haunted, unseeing faces of the GIs coming away -- the expression for it was "Thousand Yard Stare".

Michael Herr: Dislocation (The Battle of Dak To, November 1967)

I love the way you always bring the personal perspective back into the comments Tom.

ReplyDeleteI'm not sure if it's worthwhile commenting on who is made of stronger stuff. Those who appear strong may not always be so. Primo levi-in his prose at least-always seemed unruffled.

Also, isn't that sometimes just another fantasy: the strong man is the Real Dude.

Just like us can only mean something larger -- people like those who have sustained extraordinary suffering over a great duration, and endured, and survived.

I think that's spot on. For those who haven't gone through that though there's only the fantasy of association.

"old style". I wonder who in the British press matches up to that? Perhaps Fisk?

Fisk, yes, But it's an awfully short list anymore.

ReplyDeleteIt's perhaps important to keep these things in historical perspective, even if we must fall back upon our own faltering, flawad independent resources, to do so, while we still can.

No one's really fooling anyone who's conscious, even if that lot is down to being counted on one hand, in any case, I don't think.

Sy Hersh has, quite plainly, "worked the System", all along to get his stories.

How else were you going to get the stories?

The System is, and has been, fucked up beyond belief, since the period when, as Ike ruefully noted, the Permanent War Machine (he called it the military-industrial complex) took over this country.

The System is the greatest threat the planet has ever faced, whatever mask it's wearing this week, Saudi or...

The Kubrick film Doctor Strangelove is prescient in this respect. That's Kissinger up there for real, getting off on the End of the World.

Cut to America Now, same same. World get ready. Here come those cute death-bearing Republicans! And there's ol' Hank up there again in Congress! And here comes Code Pink with the handcuffs!

The war in Southeast Asia mattered a great deal in Europe, back in the day when it was Indochina. The rubber was there. Old time colonial. Bonjour François! How soon you forget.

In Paris, where I went sometime to work, the Fall of Dien Bien Phu was the stuff of major motion pictures. There was a film, something like The Four Hundred, about the last doomed French, heroically under siege.

The French to paraphrase Sterne on another subject knew about these things. Defeats, that is. The Americans, not so much.

Khe Sanh was Dien Bien Phu all over again. You'd think somebody would sooner or later try to teach somebody something about history.

Among all the writers on the modern imperialist/colonialist wars in Vietnam, one of the most interesting was Bernard Fall.

He had written beautifully of the French defeat, in Hell is a Very Small Place.

He had been, as the saying now is, embedded, with the French. (Of course, where else where was there to be at Dien Bien Phu.)

Then later, though he knew he was dying, and loved his family, leaving them to go back, and be embedded again, with the Americans, Charlie Company, and to die with them, the last sound he would ever utter being the "b" in "ambush.

He'd been vetted indeed hired by the spooks, how else could he get out there, back there, to the Street Without Joy, where the story was. Just like them, just like us.

He was a scholar, and as such an NSA contractor. The NSA, as is their wont, cut him loose and put him on the Twist In the Wind List.

The documents are here.

Bernard Fall: Death on The Street Without Joy

(And don't ever be tempted to think that any of this is a laughing matter at the spook cave to this day -- else why the unusual interest in our trivial conversation, all through the completely innocuous, totally hypothetical, entirely putative night?)

On the eve of the first Iraq War I did a long interview with Dan Ellsberg, and when it came to the Village We Had to Destroy In Order To Save It, he wept terribly, as if uncontrollably, and there was the feeling he'd been doing that for a very long time.

He had been bred from Harvard and the think tank to join the Best Minds, under Lansdale, schooled on Buchan and Lawrence of Arabia.

But something happened to even the Best Minds, there in the turmoil of the chopper wash, in the deep elephant grass of the Delta.

Perhaps relevant here also is this bit of overview from Sy Hersh, which I did not include in my edit of the interview transcript as it appears in the post:

ReplyDelete___

We just can’t — history — you know, things recede with history, but not for me, and not for many people in Vietnam. I understand that for the modern generation — you know, I remember growing up as a kid in the Second World War. The First World War was, you know, about fields of poppy and Ernest Hemingway and ambulances. So, we don’t really pay much attention to the history. But this history is pretty acute, because it does tell us about the present. We fought a war in a society where we didn’t understand the culture. We didn’t have any respect for the culture. We didn’t know the language. Our soldiers were trained incredibly poorly. The discipline was terrible. The lack of — the small-unit leadership was disgraceful. I think the Army came out of this war in terrible shape. I’d like to think it’s in better shape now. I don’t know. Many bad things still happen in the wars we’re in now in Afghanistan. As you know, I wrote about Abu Ghraib for The New Yorker a decade ago, and what happened there was very eerily similar — you know, the contempt for prisoners, the contempt for people whose societies we don’t understand.

And so, I’d like to think that, you know, just to take what I learned from Vietnam and put it into the modern context, we have been fighting the war on terror since 9/11, you know, 13, 14 years now, with drones and soldiers, and it’s only gotten worse. The fundamentalism and the hatred of America has gotten more acute. And maybe we ought to think that there’s other ways to conduct ourselves when we have opposition like we do in this case of religious opposition and opposition to our way of life and our notion of democracy. I’d really like to think that maybe we can learn something. Instead what we seem to be doing is spreading into the use of drones, so we have not even any direct responsibility, no soldiers engaging, no chance for a — you don’t have a Meadlo anymore, but you also don’t have any chance for collective guilt and collective understanding of what we do.

John Steinbeck's son, John Steinbeck lV,

ReplyDeletewas first that I knew of who was there early-on

and reported on what was really going on..

I forget for what paper... (not a mainstream paper)

He was around here for awhile... you know what happened to him ? He was kind-of "freaked out" when I met him.

see my previous comment. and

ReplyDeletethat was SOME interview on Democracy Now the other day... we've learned nothing from

what we did in Viet Nam... except that war and warfare makes the rich richer and the poor poorer... and deader !

OH MY TOM... My recollections of John Steinbeck lV just came flooding back to me... It must have been around 1970 when I met his AND

seeing this photo of him in 1968 with his dad and LBJ ... well

all this bringing tears via the memories... turns out JS lV and his buddy started a news service and where the first to publish Sy Hersh's My Lai

story...

I couldn't read this entire Wiki article...too painful:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/John_Steinbeck_IV

Ed, I was living and working as a journalist in Boulder and environs when JS was also living there. That's a whole other story. Yes, he and Sean Flynn had started up Dispatch, an early model of the "alternative" news outlet. Flynn of course was also the son of a very famous person -- in fact he became himself a legendary character, in that period, briefly, before he and the great combat photographer Dana Stone biked off into Cambodia in 1970, in search of that elusive story that would never be found. There's a good picture of Dana Stone, seventh-from-bottom, here:

ReplyDeleteMichael Herr: Sleepless at Khe Sanh / Lorenzo Thomas: Inauguration

The emotions of that war are perhaps receding as the rememberers dwindle in number and capacity to feel. But then, as we know, emotions have nothing to do with number, and only slightly more than that to do with capacity.

ahhhhh.... my muse/ subject/object in my Stone Girl E-pic

ReplyDeleteis Nguyen Doan Trang. She was born in Han Noi in 1975

and her dad got her and what was left of their family out

& to this Promised Land when she was about 10 or 12.

she now has two children, owns and operates an high-end finger-nail place on Wisconsin Ave. in Georgetown North and drives a newish BMW that she calls "My Beammer", & calls her dad "a grouch".

I recall the story of the photographer who biked-off into Cambodia ... and Steinbeck was around here in like 1966 '67 ' 68... with a gal as I recall named "The Head BooHoo. anyway... emotions aside, what else are we but our memories & phantasies ? cheers, Ed

http://www.stridemagazine.co.uk/Stride%20mag%202012/Jan%202012/edBaker.htm

Warfare is a fascinating subject. Despite the dubious morality of using violence to achieve personal or political aims. It remains that conflict has been used to do just that throughout recorded history.

ReplyDeleteYour article is very well done, a good read.