Eric Harris was shot by a 73-year-old reserve deputy who said he thought he was using his stun gun instead of his service weapon when he opened fire: photo by AP via The Guardian, 13 April 2015

Oklahoma officer charged in killing of black man after Taser 'mistake:' Sheriff’s office found fatal shooting of Eric Harris by deputy Bob Bates was ‘a mistake’ but family says: ‘This is simply evil’: Tom Dart, The Guardian, 13 April 2015

A 73-year-old insurance salesman and reserve sheriff’s deputy has been charged with second-degree manslaughter after he appeared to accidentally fire his gun instead of his Taser and shot dead an unarmed man, Eric Harris.

Harris, 44, died on 2 April after a sting operation designed to catch him selling a gun went wrong. He fled on foot but was caught and wrestled to the ground.

In video released by the Tulsa County sheriff’s office, the deputy, Bob Bates, yells “Taser”, then a shot is heard and he says: “I shot him, I’m sorry.”

A gun is visible on the ground next to Harris, who cries out in pain: “Oh God, he shot me, I didn’t do shit.”

WOW. RT @deray: in his hand: type of gun that killed #EricHarris -- on table: gun type sheriffs lied & said was used: image via Coach Kitty @CameraOnAmazon, 13 April 2015

On

Monday the district attorney, Steve Kunzweiler, told the Guardian the

sheriff’s office had provided him with the findings of its investigation

on Friday afternoon.

In filing the charges on Monday, he said: “Oklahoma law defines

culpable negligence as ‘the omission to do something which a reasonably

careful person would do, or the lack of the usual ordinary care and

caution in the performance of an act usually and ordinarily exercised by

a person under similar circumstances and conditions.”

Harris’

brother, Andre Harris, told reporters at a news conference on Monday

that officers from the sheriff’s department tried to discourage him from

hiring an attorney.

He said he did not believe the shooting was “a racial thing. I don’t

think this has anything to do with race. It might have a hint there

somewhere. … This is simply evil.”

“When

you’re the law, I guess you feel like you can do things and get away

with it and not get exposed. Well, we’ve come to expose it. We’ve come

to pull a mask off the evil.”

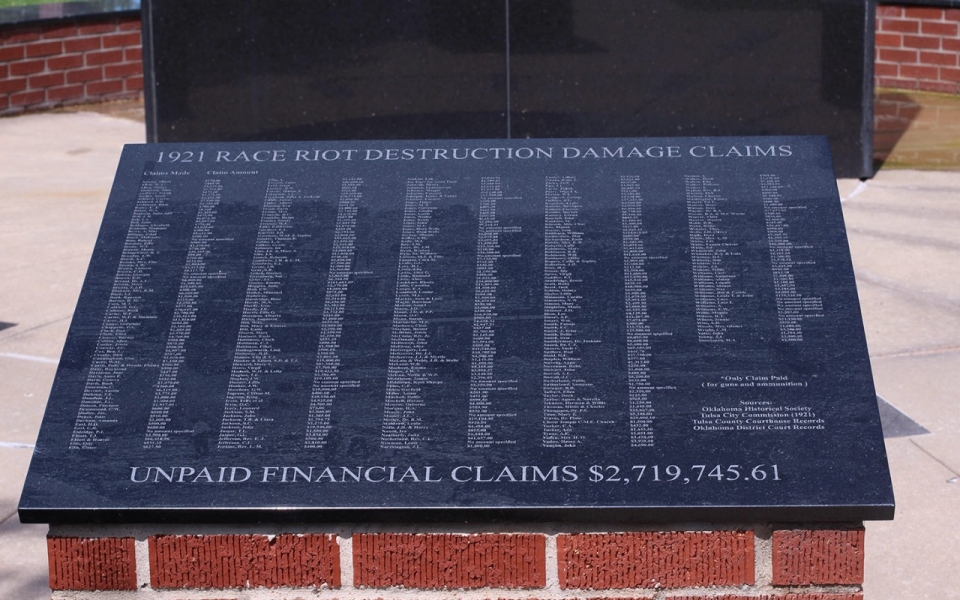

Bates,

a wealthy insurance executive in the Oklahoma city, was named

the department’s reserve deputy of the year in 2011. He worked for the

Tulsa police department for a year in the mid-1960s and is one of 130

volunteer reserves in the sheriff’s department, according to Tulsa

World, which said he had donated equipment as well as $2,500 to the

re-election campaign for sheriff Stanley Glanz in 2012.

Did the 73-year-old man who shot and killed #EricHarris pay to be a cop in his spare time?: image via CNN International @cnni, 13 April 2015

Glanz, 72, told Tulsa World he had not given his friend and fishing companion special treatment and

that the sheriff’s office once had an 81-year-old deputy. Bates simply

“made an error”, Glanz said. “How many errors are made in an operating

room every week?”

On Sunday, the Harris family issued a statement which said they “do

not believe it is reasonable for a 73-year-old insurance executive to be

involved in a dangerous undercover sting operation” and added: “We do

not believe it is reasonable -- or responsible -- for [the sheriff’s

office] to accept gifts from a wealthy citizen who wants to be [a] ‘pay

to play’ cop.”

History lives in the present. Never forget that fact. America's slave patrol police. #ericharris #walterscott: image via chauncey devega @chaunceydevega, 11 April 2015

In the video of events in Tulsa, which came from a police body

camera, officers continue to try to subdue Harris, one shouting: “Shut

the fuck up ... You ran, motherfucker, do you hear me, you fucking ran.”

When the 44-year-old says “I’m losing my breath,” an officer replies: “Fuck your breath.”

kneeling on his head, left hand grabbing neck, right hand clenched ready to punch #ericharris #firstaid: image via Mike Spangenberg @MikeSpangenberg, 11 April 2015

I

am a Black woman with asthma. I cannot even engage with "f--k your

breath" as something that one human being says to another human.

-- tweet via Ebony Elizabeth @Ebonyteach, 13 April 2015

The unimaginable cruelty of a world where a cop says "f*ck your breath" as you lay dying. Have mercy, God.

-- tweet via Yolanda Pierce @YNPierce, 13 April 2015

Hollow.

I don't have words for #EricHarris. My words won't form. His last words

- and his murderers' vile answers - keep ringing in my ear.

-- tweet via Ava DuVernay @AVAETC, 13 April 2015

-- tweet via Ava DuVernay @AVAETC, 13 April 2015

There's

not much more barbaric than continuing to physically/mentally terrorize

someone as they lay dying, screaming in fear. #Eric Harris

-- tweet via Jesse Benn @JesseBenn, 13 April 2015

-- tweet via Jesse Benn @JesseBenn, 13 April 2015

"F*ck your breath" is the experience.

-- tweet via StLNYC @StLnNYC, 13 April 2015

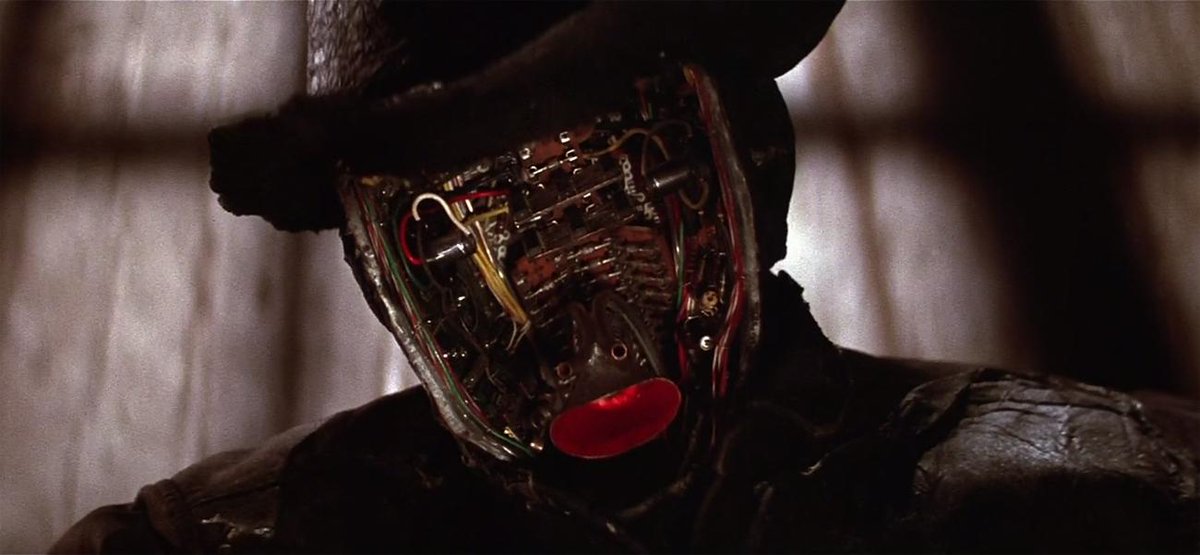

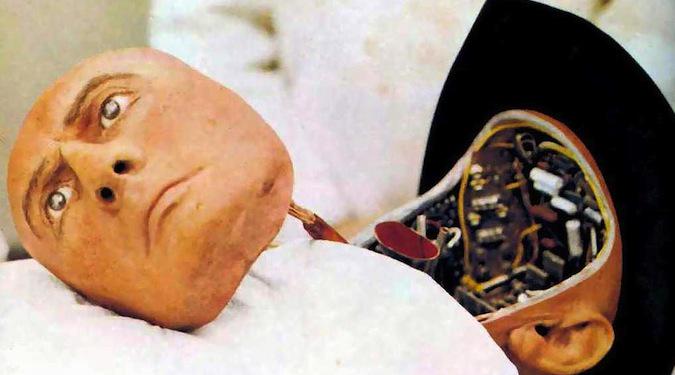

Westworld – Onde Ninguém Tem Alma | Retrospectiva #Westworld #MichaelCrichton: image via A Fábrica @Fabdeexpressos, 9 March 2015

Harris died in hospital.

In their statement, Harris’s family said: “Perhaps the most

disturbing aspect of all this is the inhumane and malicious treatment of

Eric after he was shot ... No human being deserves to be treated with

such contempt. These deputies treated Eric as less than human. They

treated Eric as if his life had no value.”

At a press conference last Friday, the Tulsa sheriff’s office said

its own investigation had concluded that Bates had made a mistake and

had not committed a crime. It brought in a Tulsa police sergeant, Jim

Clark, as a private consultant.

Tulsa Police Sgt. Jim Clark (right),

acting as an independent consultant for the Tulsa County Sheriff's

Office, and Sheriff's Capt. Billy McKelvey listen to a question during a

press conference about the shooting death of a suspect by a reserve

deputy: photo by Cory Young/Tulsa World, 11 April 2015

Clark told reporters that Bates was “a true victim of ‘slips and

capture’”, a term used to describe a mistake when someone thinks he or

she is taking one course of action but is following another.

It

was an argument used by former Oakland police officer Johannes Mehserle

to explain why he shot dead Oscar Grant at a Bart station in 2009 when,

Mehserle said, he had planned to use his Taser.

Mehserle was convicted of involuntary manslaughter. The incident inspired the 2013 film Fruitvale Station.

Oscar Grant,

shortly before being fatally shot by San Francisco Bay Area Rapid

Transit officer Johannes Mehserle, New Years Day, 2009: photo by

Associated Press

The deputy that shot and killed #EricHarris is an insurance executive who pays to play cop: image via AlexMedina @mrmedina. 13 April 2015

After the K.K.K. take off their hoods they go back to being your police, prosecutors and judges

#EricHarris #firstaid: image via Frank Clark @menes676, 11 April 2015

#MichaelCrichton Writer Series continues with #Westworld (1973): image via Motion State Review @motion_state, 8 April 2015

You are afforded the right to remain silent. #WalterScott #EricHarris: image via BlackHistoryStudies @BlkHistStudies, 13 April 2015

Steven W. Thrasher: Oklahoma and "Bad" History

If history teachers banished lessons on “bad” American history, what would be left?: photo by PhotoQuest via The Guardian, 19 February 2015

Sorry, Oklahoma. You don't get to ban history you don't like: Going after history classes that don’t teach “American Exceptionalism” is anything but patriotic: Steven W. Thrasher, The Guardian, 19 February 2015

Oklahoma

House Republicans on the Common Education Committee voted on Tuesday to

ban advanced placement US history courses, because they think [such

courses show] "what is bad about America". If I were Oklahoma, I’d want

to forget about “what is bad about” American history, too, especially in

my corner of it!

In

its “good” history, Oklahoma can boast being the basis of Rodgers and

Hammerstein musical and the home of Oral Roberts University.

But if Oklahomans were to purge all their local stories which reflect

“what is bad about America”, their history pages would be wiped as white

as a Tulsa klansman’s hood. Oklahoma was the extremely violent home to a

number of lynched African-Americans, as chronicled by America's Black

Holocaust Museum; the Native American men, women and children

slaughtered at what is now the Washita Battlefield National Historic

Site;

and the white people who killed them and likely went to church that

very week. It is where Timothy McVeigh committed the largest domestic

act of terrorism in recent years and blew up, killed and wounded

hundreds of people in the Alfred P Murrah Federal Building. Oklahoma is

chock full of former reservations

where Native Americans were forced to relocate. It’s where, just last

year, a botched execution took 45 minutes and left condemned Clayton

Lockett "a bloody mess". And it’s where the violent fracking of its

natural resources may be the reason why Oklahoma has gone from having

“one or two perceptible earthquakes a year” to “averaging two or three a

day.”

Just

last month, Education Week gave the state a D- on education and ranked

it 48th in the nation. Clearly, Oklahoma could move up from being third

dumbest, fourth most incarcerated, and sixth fattest state if it just

ignored its unpleasant history, right?

Nationally,

if history teachers were to banish everything “bad” about America from

our classrooms (i.e., the three-fifths compromise, Jim Crow, the lack of

women’s suffrage for a century and a half, the genocide of Native

Americans, the annexation of Mexico through war, the sexual assault of

one in three women in her lifetime, the apartheid of imprisoned African

Americans, Ronald Reagan, the internment of Japanese Americans,

McDonald's, the colonization of Puerto Rico, the Chinese Exclusion Act,

exporting chemical warfare, Three Mile Island, Applebee's [without

drones], TGIF’s [with drones], killing kids with drones, selling drones

to foreign countries, and Ryan Secrest,

to name just a few national disasters), and to instead only teach about

what was truly exceptional about America, what would be left to give

lessons on?

Who knew THIS SHIT could be topped by #FuckYourBreath: image via Steven Thrasher@hrasherxy, 13 April 2015

National

Republicans seem to agree with what the Okies are doing

here: when it comes to focusing too much on “bad” history (ie, not

propagating white superiority or creationism enough), Oklahoma

Republicans are in good company. Republicans in Arizona have already

banned ethnic studies in public schools. Wisconsin governor Scott Walker

wants to burnish his White House creds by cutting $300 mn from his

public university system.

Louisiana Republican Governor Bobby Jindal is also eyeing 2016 by

trying to gut $300 mn from his public university system, but from a

state which “has already cut more money, on a per-student basis, from

higher education than almost any other state in the country.”

National

Republicans aren’t any better: they blocked Democratic Senator

Elizabeth Warren’s bill to lend [money to] college students at the same

interest banks get. Senator Marco Rubio currently opposes President

Obama's plan to make community college free

because he says it doesn’t give “options” and will make the poor feel

“pressured to attend community college” just “because it’s the one

option paid for by the government.”

This

latest anti-education effort, which will only punish really

smart kids (who are the ones who want to earn college history credits

while in a high school AP course) came about because Republicans think

the coursework doesn’t shill for “American exceptionalism” enough. But

why would Oklahoma Republicans -- who embrace education "options" --

want to rob all of their brightest high school seniors of the choice

to inexpensively earn college history credits just because their history

lessons may be critical and not necessarily full of pro-American

propaganda?

If

America is exceptional for anything, it was exceptional for the

process its founders set in motion at the moment of its birth, when they

put their plans into the tangible words of the Constitution. It was an

imperfect document to be sure (that "three-fifths thing”, for example),

but words were a vastly improved repository for nationhood than a crown.

That Constitution gave us the impetus to place both our nation and

our history -- wretched and glorious alike – in writing, in a document

which could be amended, but would never be erased. We write shit down

and improve on it: that is the American exception. The written word

records our history, all of our history, in a way oral history alone can

not, especially not with the centuries-long holocaust of Americans of color.

Republicans’ efforts -- in Oklahoma

and otherwise -- to bury the past and replace it with a prettier version

are outright un-American -- in addition to being 100% ahistorical.

Holding our children’s futures hostage by refusing them the opportunity

to learn both the good and the bad is simply an effort to secure future

votes, not help children learn ... and you can’t hide the truth from

kids forever, as any parent who welcomed Santa Claus into their home

knows all too well.

Negro drinking at "Colored" water cooler in streetcar terminal, Oklahoma City, Oklahoma: photo by Russell Lee, July 1939 (Farm Security Administration Collection, Library of Congress)

Unappeased: The 1921 Tulsa race riot: "It really destroyed my faith in humanity"

Olivia

Hooker, 99, is one of the last survivors of the 1921 Tulsa

Race Riot. While her family home survived the destruction, the family

lost everything else they had -– including her father’s department store. Hooker,

who was only 6 at the time of the

riot, had never experienced racism before the mobsters burned down

Greenwood. After she witnessed white Tulsans loot her town, her

perceptions of race were dramatically altered: "It really destroyed my

faith in humanity". After 93 years of fighting for restitution, Hooker

admits it is not likely she’ll ever receive anything: photo by Al Jazeera America, 19 July 2014

Survivors

of infamous 1921 Tulsa race riot still hope for justice: Witness to the

destruction of their world, they are dying before reparations can reach

them: Dexter Mullins, AlJazeera America, 19 July 2014

The Greenwood neighborhood of Tulsa, Oklahoma, after the 1921 Tulsa race riot: photo courtesy of Tulsa Historical Society via Al Jazeera America, 19 July 2014

It was only a 1-square-mile area on the north side of Tulsa, but for

blacks in the 1900s, Greenwood was everything the South was not. Filled

with black lawyers, doctors and business owners, flush with prosperity,

here was an area where African-Americans finally had a chance to make

something of themselves, escaping the harsh racism of a nation that

deprived them of even the most basic dignities.

A dollar would circulate 19 times before leaving Greenwood, a

byproduct of the segregation laws, which kept blacks from shopping

anywhere else but also united the community financially. There was

affluence and education in Greenwood not seen anywhere else in the

country for African-Americans, and each day more people were coming to

carve out a piece of the dream for themselves, adding to the prosperity

of the neighborhood.

African-Americans taken prisoner during the riot. An armed white man rides on the running board of the truck: photo courtesy of Tulsa Historical Society via Al Jazeera America, 19 July 2014

This was the town Olivia Hooker was born in, the place she called

home as a little girl, an African-American child oblivious to the racism

plaguing the country until the day in 1921 when all of her neighborhood

would be wiped off the map in the space of a day: the bank, the elegant

brick homes, the Red Wing Hotel, Mann’s Grocery, the Dreamland Theatre,

even her father’s department store, the Sam D. Hooker Store at 124

Greenwood Avenue.

On May 30, 1921, a young black man was accused of assaulting a white

woman. That accusation was the tipping point for a town already reeling

from racial tension, and would turn into the worst 24 hours in the

city’s history, known as the Tulsa Race Riot.

Hooker is 99 now, a retired teacher living in White Plains, New York.

But when the riot happened, she was 6, exposed for the first time to

the brutal realities of discrimination and hatred. She was devastated.

“And so when this terrible thing happened, it really destroyed my

faith in humanity,” she said. “And it took a good long while for me to

get over it.”

There are fewer than a dozen survivors of the riot, which Hooker

refers to as “the catastrophe.” And for nearly a century now, the

survivors have been seeking reparations for the destruction of their

homes and businesses. Despite their best efforts, they have come up

empty-handed.

Experts and historians may have differing accounts of what happened,

but they all agree on one thing: It’s likely that the survivors will die

before they receive what they are seeking.

Thousands of families were left homeless from the fire that raged through the 35 blocks of Greenwood during the riot: photo courtesy of Tulsa Historical Society via Al Jazeera America, 19 July 2014

Tulsa wasn’t the first city to experience a race riot, and it would

not be the last. Racial disturbances were commonplace at the time, as

the nation struggled to grapple with its rapidly changing culture.

During the "Red Summer of 1919," there were more than two dozen race riots across the country. In

Chicago, tensions mounted over housing, job prospects and which race had

use of certain recreational areas, resulting in a bloody riot.

Washington, D.C., experienced its own unrest after a white woman

fabricated a story of being raped by two black men, a common lie of the

time that was then inflamed by the white press, kicking off yet another

riot.

There were similar eruptions in Knoxville, Tennessee, and Omaha,

Nebraska, that summer. And even after Tulsa, a rape accusation was the

cause of a riot in Rosewood, a black community in Florida that was

burned to the ground in 1923. In Tulsa, it all started because of an incident between Dick Rowland,

a black man, and Sarah Page, a young white woman, in an elevator at the

Drexel Building. It’s not exactly clear what the chain of events was --

even the state’s official report lists a variety of stories surrounding

what happened -- but most credible accounts agree on the basic facts.

On May 30, 19-year-old Rowland was riding in an elevator operated by 17-year-old Page. Rowland

tripped as he was exiting the elevator and grabbed Page’s arm in an

attempt to steady himself. She screamed, and he fled the elevator as a

white clerk from a nearby store came to investigate the noise. He

assumed Page, apparently distraught from the incident, had been

assaulted by Rowland and called the police.

Like a game of telephone, the story became more inflammatory with

each retelling, and spread rapidly. Rowland hid in Greenwood, terrified

he’d be lynched for allegedly raping a white girl. He was arrested the

next morning and taken to the courthouse, where a vigilante mob had

arrived to demand that police turn him over to the crowd.

Armed white men ride with a few black men in the car during the riot: photo courtesy of Tulsa Historical Society via Al Jazeera America, 19 July 2014

A group of black men, many of them World War I veterans, armed

themselves and went to the courthouse to protect Rowland, determined

that a black person would not be lynched in their town.

More than 75 of them twice arrived at the courthouse to offer their services to defend Rowland against a mob of thousands of angry whites. They were twice denied. Their departure from the courthouse the second time would be the tipping point.

According to the official report, a white man approached one of the black men, who was armed with a revolver.

“Nigger, what are you going to do with that pistol?” he said.

“I’m going to use it if I need to,” the black man replied.

The white man demanded he hand it over, and he refused. When the white man tried to disarm him, the gun went off and the riot began.

Over the course of 24 hours, Greenwood would be looted, set ablaze and literally burned off the map. All 35 blocks were gone.

When the smoke cleared on June 1, more than $1.5 million in damage (about $20 million in contemporary dollars) had been done; as many as 300 people, black and white, had been killed; and thousands of black families were left homeless, with nothing but rubble and ash to call home.

More than 75 of them twice arrived at the courthouse to offer their services to defend Rowland against a mob of thousands of angry whites. They were twice denied. Their departure from the courthouse the second time would be the tipping point.

According to the official report, a white man approached one of the black men, who was armed with a revolver.

“Nigger, what are you going to do with that pistol?” he said.

“I’m going to use it if I need to,” the black man replied.

The white man demanded he hand it over, and he refused. When the white man tried to disarm him, the gun went off and the riot began.

Over the course of 24 hours, Greenwood would be looted, set ablaze and literally burned off the map. All 35 blocks were gone.

When the smoke cleared on June 1, more than $1.5 million in damage (about $20 million in contemporary dollars) had been done; as many as 300 people, black and white, had been killed; and thousands of black families were left homeless, with nothing but rubble and ash to call home.

The damage to the Williams Dreamland Theatre in Greenwood: photo courtesy of Tulsa Historical Society via Al Jazeera America, 19 July 2014

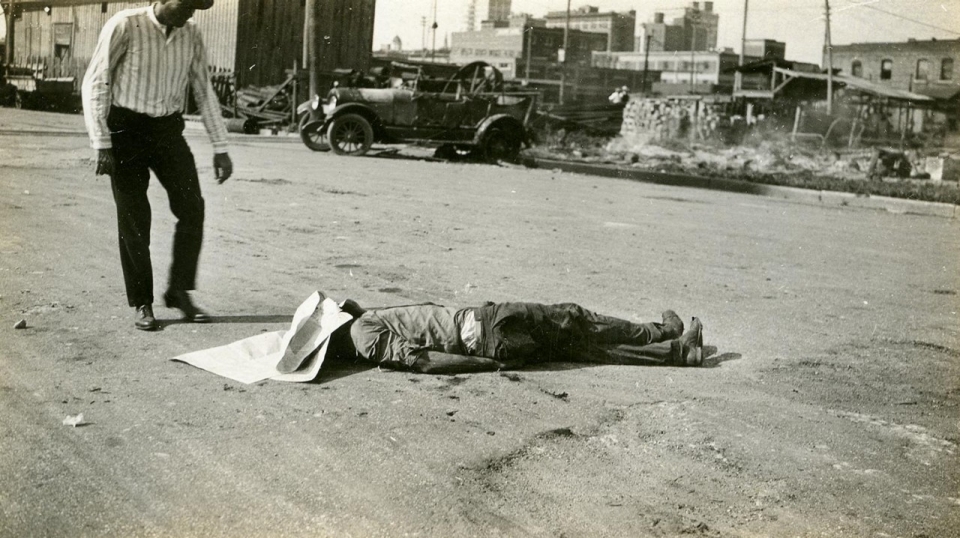

Even then, there were people who wanted to pay restitution.

According to a 1921 New York Times article,

Judge Loyal J. Martin, a former mayor of Tulsa who chaired the first

race riot committee -- the Tulsa City Commission -- just days after the

attack, said in a mass meeting that the city could redeem itself and

move forward only “by complete restitution and rehabilitation of the

destroyed black belt.”

"The rest of the United States must know that the real citizenship of

Tulsa weeps at this unspeakable crime and will make good the damage, so

far as it can be done, to the last penny,” he said.

But that never happened. Insurance companies denied claims from

African-Americans, leaving them with nothing but the clothes on their

backs, forced to start over or leave. Blacks tried to sue the city and

state for damages but had their claims blocked or denied, according to

the official report.

On June 14, just two weeks after the riot, Mayor T.D. Evans addressed

the commission, telling it that the incident was “inevitable” and that

the victims “should receive such help as we can give them.”

But then he said something else: “Let us immediately get to the

outside fact that everything is quiet in our city, that this menace has

been fully conquered, and that we are going on in a normal condition.”

In other words: The city should move on. And for 90 years, that’s what happened.

After an initial flurry of reports, with articles appearing as far

away as the London Times, news of the “troubles” in Tulsa vanished.

A Tulsa man is detained during the riot: photo courtesy of Tulsa Historical Society via Al Jazeera America, 19 July 2014

Greenwood did rebuild, bigger and better

than it was before. But desegregation claimed Greenwood just as it did

every black town in the United States; given the opportunity to spend

money outside their own neighborhood for the first time, and the chance

to live in areas previously off limits to them, African-Americans slowly

but steadily moved away from the area, and the businesses left with

them.

The Greenwood of today looks nothing like the once famous area. A

highway overpass cuts right through the middle of the neighborhood. The

sidewalks along Greenwood Avenue and Archer Street are lined with

hundreds of plaques that each list the name of a business that was

destroyed in the riot and whether or not it was rebuilt. Many were not.

But just behind the businesses on Greenwood Avenue is a shiny new

baseball stadium, and across the street is a new luxury condominium

building. A large chunk of Greenwood is now home to the Tulsa campuses

of both Oklahoma State University and Langston University.

An armed man during the riot: photo courtesy of Tulsa Historical Society via Al Jazeera America, 19 July 2014

From the time of the riot, whole

generations of Tulsans have grown up never hearing a word about the

darkest moment in the city’s history.

Damario Solomon-Simmons, an African-American attorney in Tulsa, is one of them.

A native of North Tulsa, Solomon-Simmons attended Carver Middle

School -- on Greenwood Avenue -- and still didn’t learn about Greenwood

and the riots until he took an African-American studies course at the

University of Oklahoma.

All of it -- the business district and the homes, the sudden

destruction -- left him flabbergasted. He argued with his professor,

telling him, “You’re wrong! I’m from Tulsa, I’m from North Tulsa, I’ve

never seen or heard of anything like that.’’

Marc Carlson, a historian and archivist at the University of Tulsa

who oversees the school’s race riot collection, said many of his

students don’t know either, not even the ones from Tulsa.

“I don’t know why that is,” he said, adding that the state Legislature requires schools to include the riot in their curriculum.

Oddly, there is more awareness of the event in other countries than in the U.S.

Michelle

Place, executive director of the Tulsa Historical Society, said

requests for information about the riot are the society’s No. 1 inquiry.

"About a month ago I talked to someone in New Zealand. I’ve talked to Tokyo, I’ve talked to London,” said Place.

She can understand why city leaders might be reluctant to put it in

school textbooks. But why, she wondered, didn’t the tale survive orally?

“The fact that it’s not just one of those things that we all knew

took place,” she said and paused, “… takes my breath away, brings me up

short.”

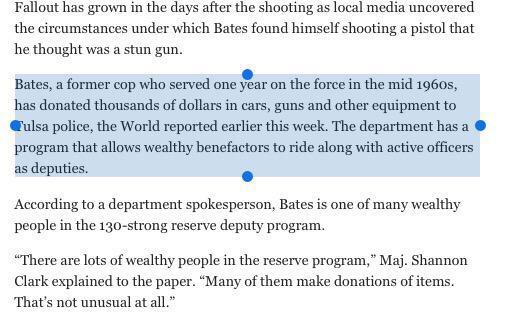

A dead body in the street, June 1, 1921: photo courtesy of Tulsa Historical Society via Al Jazeera America, 19 July 2014

Despite suffering massive losses from the riot, many people in the

black community did not and still do not know about it, said Mechelle

Brown, program coordinator at the Greenwood Cultural Center.

Many whites were ashamed of the incident, she said, so it would make

sense that they wouldn’t want to talk about it. But it was also hushed

up in the black community. Why, she wondered, wouldn’t they want people

to know what happened to them?

Firefighters extinguish the flames during the riot: photo courtesy of Tulsa Historical Society via Al Jazeera America, 19 July 2014

“But blacks, we asked years ago, ‘Why did you not talk about it?’ And

they said that after the race riot, when they came back here and there

was absolutely nothing to come home to, that they felt those same

feelings of anger and resentment and bitterness and fear,” Brown said.

“But they had to think about the next day, and the day after.”

Brown understands why they wouldn’t want to relive that pain, she said. At the same time, she sees it as a missed opportunity.

“It robbed us of something. It robbed us of our history. It robbed us of where we come from.”

A Ku Klux Klan gathering in Drumright, Oklahoma, 1922. The Klan's presence in Oklahoma increased after the riot: photo courtesy of Tulsa Historical Society via Al Jazeera America, 19 July 2014

In

2001, 80 years after the destruction of Greenwood, the Tulsa Race Riot

Commission recommended in a 178-page report that survivors be paid

reparations, calling it a “moral obligation.”

“Justice demands a closure as it did with Japanese Americans and

Holocaust victims of Germany,” the report reads. The issue is not if

reparations are to be paid, but “which government entity should provide

financial repair to the survivors and the condemned community that

suffered under vigilante violence?”

Paying reparations was just not something Oklahomans were interested in entertaining.

Brown said that almost as soon as word got out about the possibility

of reparations, the Greenwood Cultural Center began to receive hate mail

and angry, anonymous phone calls from people who did not support paying

out. A lot of the calls were similar: “I wasn’t here, my parents

weren’t involved in it.”

The Oklahoma state Legislature accepted the report and the “moral

responsibility on behalf of the state and its citizens” but flatly

refused to pay any type of reparations.

More than 200 people sued the state, seeking recourse for damages.

The survivors weren’t asking for individual checks for themselves or

their descendants; they wanted educational benefits such as scholarships

for students in the area to attend historically black colleges and

universities and health benefits for descendants who remained in

Greenwood.

Unfortunately,

Oklahoma law requires that civil rights lawsuits be filed within two

years of an event, and District Judge James O. Ellison noted that the

clock began ticking right after the riot. The U.S. Supreme Court said

the same.

Thousands of families were left homeless from the fire that raged through the 35 blocks of Greenwood during the riot: photo by Dexter Mullins for Al Jazeera America, 19 July 2014

For Solomon-Simmons, an attorney who worked with the victims’ legal

team, having the case denied by the nation’s highest court just added

insult to injury.

“I felt like we were right. We had the facts on our side. I think we

should have had the law on our side,” he said. “I still get exceedingly,

if I’m frank, pissed off, just thinking about the fact that we were not

able to get redress for the survivors and their descendants.”

Tulsa did construct the John Hope Franklin Reconciliation Park

in the middle of Greenwood, a memorial to the destruction and a tribute

to the survivors. It’s one of two monuments in the area -- the other is

in front of the Greenwood Cultural Center and was built with money

raised exclusively by the center several years before the reconciliation

park.

The Mabel B. Little Heritage House, one of the few homes to survive the riot, is maintained by the Greenwood Cultural Center. The home is filled with items typical of a home in 1920s Greenwood: photo by Dexter Mullins for Al Jazeera America, 19 July 2014

Despite articles appearing in publications over the years, most people in the U.S. still have no idea the event

even occurred. There is a major push from the Tulsa Historical Society,

the Greenwood Cultural Center and the University of Tulsa to fix that.

The

historical society has digitized its riot archive and put the

collection onto an app, hoping to satisfy the seemingly unyielding

demand for information about the riot, and to reach new people.

The app launched in May for $9.99, and as more material comes in, it

will update so people can see the latest information. UT is also

digitizing the cultural center’s archives so the information can be

shared online.

The survivors may not have won their case, but at least now people may finally learn about the prosperity they once had.

After they lost their appeals, not much has happened in the way of

paying the few remaining survivors. Old age and time has claimed the

lives of many of them, and more die every year without any restitution.

There are some efforts in Congress to try and help. Rep. John

Conyers, D-Mich., introduces a bill every year on the floor of the House

to remove the statute of limitations in the Greenwood case to allow the

survivors’ lawsuit to go forward.

But that bill -- along with the one

Conyers presents each year to study reparations for slavery -- is not

likely to ever get further than that introduction, especially in today’s

divided Congress.

“We thought we might live long enough to see something happen, but

even though I’ve lived 99 years, nothing of that sort has actually

happened,” Hooker said. “You keep hoping, you keep hope alive, so to

speak.”

After all, it did take 80 years before the survivors of the riot even

got an official apology from the city of Tulsa. Mayor Kathy Taylor held a “celebration of conscience” and honored with a medal each of the survivors the city could contact.

But Hooker,who was the first African American woman to serve in the

Coast Guard and went on to earn a doctorate's in psychology, remains

optimistic.

“We’ll just keep right on trying, never giving up. Never, never giving up.”

Solomon-Simmons, on the other hand, isn’t nearly as hopeful.

The collective failure to act, to pay the victims, to set up a

scholarship fund or make a real attempt at restitution is a “stain on

our nation,” he said.

“And it’s sad to know that they’re probably all going to die without

receiving anything,” he added. “Unfortunately, black life in America is

still not worth that much.”

Sculptor Ed Dwight created three statues to convey the hostility, humiliation and hope experienced by the Greenwood neighborhood. Found in the John Hope Franklin Reconciliation Park, this statue represents humiliation: photo by Dexter Mullins for Al Jazeera America, 19 July 2014

.

ReplyDelete.

.

.

.

guess I should donate

something to the police

like a soul

since I'm not using mine

but wait

I can't seem to find it

.

.

.

.

Oklahoma! ("Plenty of room to swing a rope...")

ReplyDeleteTulsa, OK Cops Kill Unarmed Black Man Shooting Him In The Back: "In America, a dog is worth more than Eric Harris"

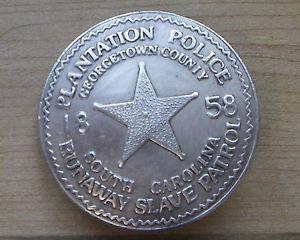

RUNAWAY SLAVE PATROL?

ReplyDelete