Article of clothing worn by a victim of the 6 August 1945 atomic bombing of Hiroshima, seen in the archive of the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum: photo by Ishiuchi Miyako From “Here and Now: Atomic Bomb Artifacts, ひろしま/Hiroshima 1945/2007—"; image via Behold, 27 August 2014 (Andrew Roth Gallery)

I come and stand at every door

But no one hears my silent tread

I knock and yet remain unseen

For I am dead, for I am dead.

I'm only seven although I died

In Hiroshima long ago

I'm seven now as I was then

When children die they do not grow.

My hair was scorched by swirling flame

My eyes grew dim, my eyes grew blind

Death came and turned my bones to dust

And that was scattered by the wind.

I need no fruit, I need no rice

I need no sweet, nor even bread

I ask for nothing for myself

For I am dead, for I am dead.

All that I ask is that for peace

You fight today, you fight today

So that the children of this world

May live and grow and laugh and play.

Nâzim Hikmet Ran (1902-1963): Kız Çocuğu (The Little Girl), translated by Jeanette Turner as I Come and Stand At Every Door

"In the late '50's I got a letter: 'Dear

Pete Seeger: I've made what I think is a singable translation of a poem

by the Turkish poet, Nazim Hikmet. Do you think you could make a tune

for it? (Signed), Jeanette Turner.' I tried for a week. Failed.

Meanwhile I couldn't get out of my head an extraordinary melody put

together by a Massachusetts Institute of Technology student who had put a

new tune to a mystical ballad The Great Silkie from the Shetland

Islands north of Scotland. Without his permission I used his melody for

Hikmet's words. It was wrong of me. I should have gotten his permission.

But it worked. The Byrds made a good recording of it, electric guitars

and all."

Pete Seeger (1919-2014), from Where Have

All the Flowers Gone: A Singer's Stories, Songs, Seeds, Robberies (A

Musical Autobiography), 1993

Article of clothing worn by a victim of the 6 August 1945 atomic bombing of Hiroshima, seen in the archive of the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum: photo by Ishiuchi Miyako From “Here and Now: Atomic Bomb Artifacts, ひろしま/Hiroshima 1945/2007—"; image via Behold, 27 August 2014 (Andrew Roth Gallery)

Article of clothing worn by a victim of the 6 August 1945 atomic bombing of Hiroshima, seen in the archive of the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum: photo by Ishiuchi Miyako From “Here and Now: Atomic Bomb Artifacts, ひろしま/Hiroshima 1945/2007—"; image via Behold, 27 August 2014 (Andrew Roth Gallery)

Article of clothing worn by a victim of the 6 August 1945 atomic bombing of Hiroshima, seen in the archive of the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum: photo by Ishiuchi Miyako From “Here and Now: Atomic Bomb Artifacts, ひろしま/Hiroshima 1945/2007—"; image via Behold, 27 August 2014 (Andrew Roth Gallery)

Article of clothing worn by a victim of the 6 August 1945 atomic bombing of Hiroshima, seen in the archive of the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum: photo by Ishiuchi Miyako From “Here and Now: Atomic Bomb Artifacts, ひろしま/Hiroshima 1945/2007—"; image via Behold, 27 August 2014 (Andrew Roth Gallery)

Article of clothing worn by a victim of the 6 August 1945 atomic bombing of Hiroshima, seen in the archive of the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum: photo by Ishiuchi Miyako From “Here and Now: Atomic Bomb Artifacts, ひろしま/Hiroshima 1945/2007—"; image via Behold, 27 August 2014 (Andrew Roth Gallery)

Article of clothing worn by a victim of the 6 August 1945 atomic bombing of Hiroshima, seen in the archive of the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum: photo by Ishiuchi Miyako From “Here and Now: Atomic Bomb Artifacts, ひろしま/Hiroshima 1945/2007—"; image via Behold, 27 August 2014 (Andrew Roth Gallery)

80,000 insanın bir anda, 200,000 insanın sonraki yıllarda ölmesine neden olan saldırıyı yapan #Enola Gay adlı uçak: image via Murad @muradcobanoglu, 6 August 1945

Hiroşima'da yüz binlerce insanın ölümüne neden olan #Enola Gay adlı uçağın kaptan pilotu Tuğg. Paul Warfield Tibbets.: image via Murad @muradcobanoglu, 6 August 1945

Hiroşima'da yüz binlerce insanın ölümüne neden olan #Enola Gay adlı uçağın kaptan pilotu Tuğg. Paul Warfield Tibbets.: image via Murad @muradcobanoglu, 6 August 1945

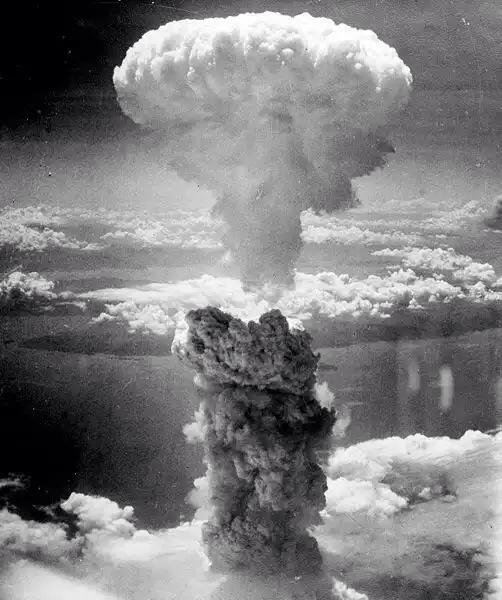

#TarihteBugün: ABD, 80,000 insanın ölümüne neden olan ilk atom bombasını 1945'te Japonya'nın Hiroşimakentine attı.: image via Murad @muradcobanoglu, 6 August 1945

#TarihteBugün: ABD, 80,000 insanın ölümüne neden olan ilk atom bombasını 1945'te Japonya'nın Hiroşimakentine attı.: image via Murad

@muradcobanoglu, 6 August 1945

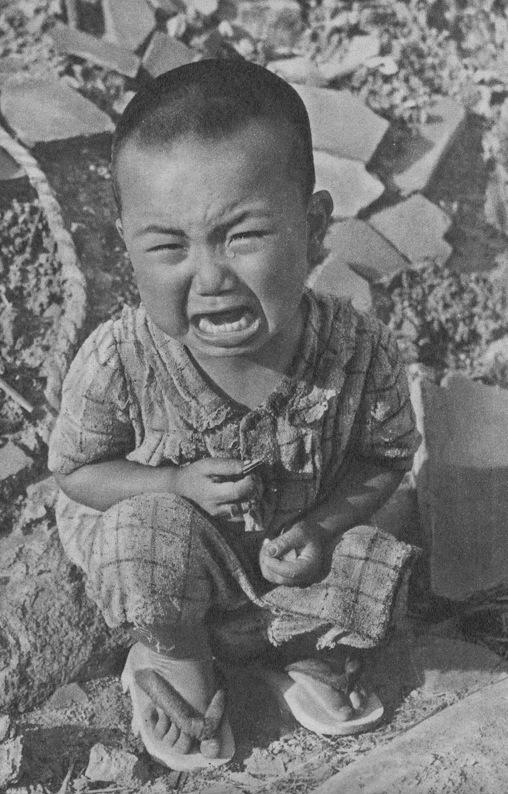

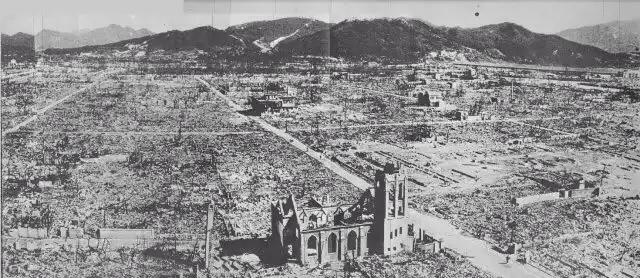

Hiroshima 6 Agosto 1945

70 Anni fà ... #Pernondimenticare Che l'uomo ha dominato l'uomo a suo danno...: image via nando mele @mele_nando 6 August 2015 Milan, Lombardy

Hiroshima 6 Agosto 1945 70 Anni fà ... #Pernondimenticare Che l'uomo ha dominato l'uomo a suo danno...: image via nando mele @mele_nando 6 August 2015 Milan, Lombardy

August 6, 1945: United States dropped the 1st (of

2) atomic bomb on Hiroshima, Japan: est. 140,000 deaths.: image via

History #HistoryTime, 6 August 2015

Hiroshima 6 Agosto 1945 70 Anni fà ... #Pernondimenticare Che l'uomo ha dominato l'uomo a suo danno...: image via nando mele @mele_nando 6 August 2015 Milan, Lombardy

The shadows of the parapets are imprinted on the surface of the bridge, 2,890 feet (880 meters) south-south-west of the hypocenter. These shadows give a clue as to the exact location of the hypocenter: photo by U. S. Army, August 1945

Kız Çocuğu (Nazım Hikmet) ~ Fazıl Say

ReplyDeletePete Seeger Marks the 68th Anniversary of Hiroshima bombing by Singing I Come and Stand At Every Door (2013)

Black Mamba reads I Come and Stand At Every Door {2006)

The Corries: The Great Silkie of Sule Skerry

beautiful and touching verse!

ReplyDeleteThanks for this one, Tom. It's a beautiful & affecting poem. As you know, it's pretty hard to write a simple Blakean ballad like this & have it come out so well. I loved Pete Seeger---saw him a number of times in the 60s & then shared the bill with him when he and Celtic Thunder (and I can't remember who else) did some kind of labor salute to Sean O'Casey in Manhattan, probably in the late '80s. And the Weavers: I was a major fan of theirs when I was a kid. Had all their LPs memorized. But I'm a little irritated at Pete's borrowing "without permission" someone else's music & compounding the situation by not even naming the MIT student. But maybe I'm taking him out of context. Hikmet, too: what a virtuoso. I think I like the Byrds rendition of the song version of this poem the best. (As for the Corries and that weird sitar-like instrument: I would not want to be stoned while trying to tune that thing.)

ReplyDeleteHeartbreaking. Thank you for these images, Tom.

ReplyDeletehttps://www.youtube.com/watch?v=IYxwQCqHkRw

ReplyDeleteI had to struggle to scroll down. My parents were heavily involved in CND but I'd never seen the images of the clothes before. It was like learning of the horror for the first time.

ReplyDeleteI ask for nothing for myself

For I am dead, for I am dead.

How can you wipe away those smiles by the Enola Gay? They leave a stain on the mind.

Many thanks to all for moving testimony.

ReplyDeleteTerry, rest assured the credit situation had long since been settled up fair and square by the time Pete Seeger, at 90, did that amazing a capella version for Democracy Now.

The song is now and forever copyighted c Nazim Hikmet/James W. Waters.

Here's the easy way to get to Hilton's link: this is where I reckon Terry and Hilton and indeed most of us who are older first became aware of the great Hikmet's poem without yet knowing he was at the time already, quite possibly, the century's premier world poet -- the Byrds' version of Hikmet's lyric, midwifed by Pete Seeger, recorded nearly half a century ago (early 1966, to be exact):

The Byrds: I Come and Stand at Every Door (from Fifth Dimension, 1967

__

About the first set of images here, photos by Ishiuchi Miyako (b. 1947 Japan), the curator of her exhibition had a bit to say concerning her motives and procedure in an introduction contributed by Jordan G. Teicher of Behold:

__

[quoting:]

In 2007, the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum opened its archive to Ishiuchi, and since then she’s photographed hundreds of artifacts. Some of the objects came from bombed buildings or were found on the streets; others came from families who held onto items for decades after the blast. People are still coming into the museum to donate, Roth said. “It's not a nostalgic project. She’s not interested in that. She’s not even really interested in the history of what happened in Hiroshima because it’s known. She's more interested in the life of these objects she's photographing and the life that's there now,” he said.

Early on in her project, Ishiuchi photographed the objects on a light table, making the items of clothing translucent. She then shifted to photographing off the table and in the daylight, making the photographs more “about the physical thing itself.” All of the objects are fragile, so museum staff set each one out carefully for Ishiuchi on a tabletop or on the floor. “Since she’s often had an interest in how the body ages, she’s careful to choose artifacts to photograph that had contact with the body. That's why most artifacts are articles of clothing. They’re the extra layer that drapes over the skin of a body. Even the other artifacts—the shoes, the makeup kits, the wristwatch -- had contact with the body somehow,” he said.

Sometimes Ishiuchi photographs a full article of clothing. Other times, she zooms closer on the details or scars on the surface of the objects. “It's the body that she’s interested in and these artifacts take on a kind of life. I don’t think she's trying to get back to who the person was who was wearing the dress, for instance. It's more about getting to know the dress or the shirt today and what it has to say,” Roth said.

[ending quote]

__

The exhibition contains a variety of artifacts. I've shown here only items of dress that might have been worn by the poet's titular "little girl", or perhaps her sister, mother, grandmother...

Meanwhile, as this is blogging, I suppose I ought to put in that my first remembered personal awareness of a specific date in world history arrived on a morning nearly seventy years ago when the bold banner headline of the daily Chicago Tribune seemed momentous -- at least, it was having that effect on adults, who were the judges of what is momentous. The headline read, as I recall, JAPS SURRENDER!

ReplyDeleteThis was meant of course to signify a famous victory.

Yet my childhood, as that of many urban American children of the period, was shadowed by fears hatched from that supposed triumph. American triumphalism is always like that. Today the great victory. Tomorrow the uncontrollably proliferating horrors, disguised as further victories.

Hiding under your school desk or tacking blankets over your windows at home did not perhaps seem the celebratory behaviour of a gloriously triumphant people, still for some years that became routine.

Many years later it came to pass that I wore the military uniform of this victorious people and attended academic classes in the geography and logistics of hypothetical nuclear wars all across the globe. In this same period, at one point the imminent threat of a nuclear war gripped the campus. On a chilly dawn in the dormitory parking lot, hundreds of red-kneed sorority girls in plaid kiltlike skirts with big ornamental safety pins were being loaded into station wagons by anxious dads, to be ferried off to the relative safety of Grand Rapids or Kalamazoo.

Still more years later I learned in conversation with Dan Ellsberg just how close those skirts had come to becoming articles later found in some archive of apocalyse, like those photographed in the archives of the Hiroshima Peace Museum by Ishiuchi Miyako.

Michael Hiltzik, a Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist, has just come out with a book that reminds one all over again: it's impossible to escape the shadow of nuclear apocalypse, no matter how far one flees. The genie is out of the bottle, just having a rest break.

ReplyDeleteIn “Big Science: Ernest Lawrence and the Invention That Launched the Military-Industrial Complex,” Hiltzik rubs it in.

I dwell and cower in the town where ultimate human evil, in the disguise of Big Science, was loaded onto the dock of the elevated plateau from which it presently dominates, and threatens to extinguish, all life, by means not merely of nuclear weapons, but of a vast panoply of new, benign-sounding "tools" and "apps" and the like.

I've heard Hiltzik speak in an interview about the book. Lucid, chilling listening. The parable of Big Science vs Little Earth is awful to consider. A one-sided contest from the first.

And just up yon hill, the Big Science money's still flowing even as the water's giving out for all but the wrongest uses, the ghosts of the native Indians are still drifting restlessly through the yellowing oaks, and the grant-motored death-tech-heads are still hard at it.

Robert Crease reviewed Hiltzik's book last month in NYTBR. Hiltzik, writes Crease,

[quoting:]

provides a solid account of the early days of the trend toward such gargantuan projects. Its progenitor was Ernest O. Lawrence, an intense and ambitious South Dakota youth whose passionate inquisitiveness, practical abilities and scientific intuition drew him to experimental physics. With a forgivable touch of false journalistic precision, Hiltzik identifies the birth date of Big Science as a spring day in 1929 when Lawrence, a 28-year-old associate professor at the University of California, Berkeley, realized he could create a new scientific tool by turning particles into bullets. Instead of using lots of energy all at once to kick particles down a straight barrel as others were doing, Lawrence would send them in circles, giving them a gentle push with each lap. Lawrence spent the next decade welding together science and engineering in ever bigger “cyclotrons,” as they were jokingly called. Indispensable tools of nuclear physics, cyclotrons grew in diameter from four inches to 11 inches, 27 inches, 37 inches and 60 inches — and increased in cost from less than $100 to tens of thousands of dollars — with a stupendous 184-inch machine in the works by 1939, the year Lawrence won the Nobel for the achievement.

Lawrence’s greatest contribution, however, was not building any specific cyclotron — a task often delegated to others — but creating the infrastructure that made them possible. His was less a scientific than a managerial genius. He learned how to feed the ambitions of wealthy and powerful patrons. To university administrators he promised prestige, to biologists medical isotopes, to industrialists new materials and energy sources, to philanthropists glory.

In 1931, Lawrence acquired his own building for cyclotron research, the “Rad Lab.” From the outside, one visitor recalled, the two-story wooden shack resembled “a secondhand tin shop, a dinky little place.” Inside, science was undergoing a phase change. The Rad Lab’s environment was nearly egalitarian, strongly collaborative and generally exciting — no closed doors, no private ownership of equipment or ideas. The only authority was the cyclotron. It was the theater, the humans its stagehands.

[Crease on Hiltzik's Big Science, continuing:]

ReplyDeleteOne of Lawrence’s closest friends was J. Robert Oppenheimer. The two were “a most enigmatic pair,” Hiltzik writes — the extroverted, well-groomed and apolitical Lawrence, whose parents were Midwestern Lutherans, contrasted with the moody, ruminative and leftist Oppenheimer, whose parents were wealthy secular Jews from Manhattan’s Upper West Side. The book contains a photograph of the two in which Lawrence, neat and grinning, stands alert and balanced “like a youthful Mark Antony,” while Oppenheimer slouches against a Packard, James Dean-like, “his hair an unkempt mop, his eyes glaring mistrustfully at the lens from under hooded brows.” The two ruled American physics in the 1930s; Lawrence its experimental, Oppenheimer its theoretical wing.

Lawrence had a dark side. His cockiness and haste undermined some of the Rad Lab’s early scientific work, causing it to miss some discoveries and make embarrassing mistakes. But he learned from these episodes, incorporated more rigor into the laboratory’s work and redoubled his efforts.

World War II wrought another phase change. Lawrence was deeply involved with the Manhattan Project and got along famously with its head, Gen. Leslie Groves. He rescued the bomb project from cancellation and helped install Oppenheimer as leader of the Los Alamos laboratory, promising to take over if Oppenheimer failed. Lawrence’s devices separated the uranium used in the Hiroshima bomb, and produced the first samples of the plutonium used in the Nagasaki bomb.

As the Manhattan Project’s huge scientific-engineering juggernaut rolled into action, Big Science finally began to outrun Lawrence’s ability to control it. He built huge cyclotron-like separators, called calutrons, to make uranium bomb fuel — but the original one failed when its powerful magnets threatened to pull the machine apart. For the first time in his career, Hiltzik writes, Lawrence was faced with “an engineering crisis he could not fix himself.” Exhausted, depressed, tortured by back spasms, he checked himself into a hospital.

He recovered, and by the end of the war was dreaming up dramatic new possibilities, which produced “a transformation of American science as profound as any change inspired purely by scientific discovery: the launch of peacetime government patronage.” But realizing these ambitions required cultivating political and military leaders, and the formerly apolitical Lawrence found he could no longer keep political issues out of the Rad Lab.

Lawrence’s dark side now grew darker. He refused to repudiate the controversial University of California Regents’ requirement that all employees sign a loyalty oath, which caused several Rad Lab scientists to leave. He founded a weapons lab to develop the hydrogen bomb that still bears his name (Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory). When Oppenheimer’s security clearance was revoked, in part because of his earlier left-wing activities, Lawrence initially agreed to testify against his old friend. (Belatedly realizing this would damage the Rad Lab, he backed out of testifying, citing a debilitating attack of colitis and showing visitors his bloody toilet as proof.) He opposed a proposed nuclear test ban during the 1956 presidential election. In 1958, Lawrence attended a conference on test-ban inspections in Geneva that taxed his health. He died a few weeks after returning.

Hiltzik’s tale is important for understanding how science and politics entwine in the United States...

(ending quote]

And finally, Duncan, those happy Enola Gay crewmen and their spiritual descendants have just gone on smiling, pretty much, as this poll so very depressingly (yet not unsurprisingly) suggests:

ReplyDelete__

56% of Americans still believe Hiroshima bombing was justified – poll: RT: Question More, 6 August 2015

Seventy years after the first atomic bomb was dropped on Hiroshima, destroying tens of thousands of lives, a new poll shows that most Americans still believe the nuclear attacks on the city and Nagasaki were justified.

More specifically, 56 percent of Americans think the use of atomic weapons against Japan during World War II was justified, according to a new poll by the Pew Research Center. Meanwhile, 34 percent said their use was not justified.

While the number of Americans supporting the bombings has dropped nearly 30 percent since the immediate aftermath of the war – a 1945 Gallup poll found 85 percent in support – the number appears to have remained steady over the last decade. A 2005 Gallup poll found that 57 percent of Americans approved of the twin bombings.

The latest poll did find that attitudes have changed most dramatically in the younger generation of Americans. Another large gap was observed between registered Democrats and Republicans.

“Seven-in-ten Americans ages 65 and older say the use of atomic weapons was justified, but only 47 percent of 18- to 29-year-olds agree,” Pew stated. “There is a similar partisan divide: 74 percent of Republicans but only 52 percent of Democrats see the use of nuclear weapons at the end of World War II as warranted.”

In Japan, the poll unsurprisingly found that the public adamantly believed that destroying Hiroshima and Nagasaki with nuclear weapons was not justified. Seventy-nine percent of the Japanese said it was not, while 14 percent said that it was.

The bombing of Hiroshima is estimated to have killed anywhere between 66,000 to 150,000 people, mostly civilians.

["56% of Americans still believe Hiroshima bombing was justified – poll" -- continuing:]

ReplyDeleteIn America, the debate over President Harry Truman’s decision to unleash the weapons has continued to be a controversial topic even in spite of majority support for it.

Those critical of the decision have presented a litany of arguments against it, including the contention that the atomic bomb was only meant to be used defensively, if ever, and that its real purpose was to act as a deterrent. As a way of defending this argument, they note that outside of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, the bomb has only been used to deter opponents.

Opponents also state that the bombs’ use was intended more as a way to intimidate the Soviet Union than as a way to bring about an end to the war, since the Soviets were planning to declare war on Japan and aid the US just about a week after the first bomb dropped on Hiroshima. Others say there were alternatives to ending the war, such as permitting the emperor to remain as a powerless figurehead. If the US really wanted to demonstrate the power of the atomic bomb, it could have also conducted a test demolition as a warning.

Speaking with RT, Madelyn Hoffman of New Jersey Peace Action, said the “utter, total devastation and destruction of lives” that occurred was not worth the US deploying the weapons as “a flex of the muscle.”

“History, I believe, has shown that Japan was ready to surrender, that the dropping of the bombs was not necessary, and that they were dropped more to show US strength towards the former Soviet Union than anything that was going on in the war,” she added.

Those who believe that it was justifiable to drop the bombs often argue that, compared to a land invasion of the main Japanese islands, Truman’s decision saved tens of thousands of American lives. According to the Authentic History Center, US military studies suggested that America could suffer anywhere between 23,000 and 49,000 casualties in the first 30 days of an invasion alone. Estimates for total casualties, meanwhile, projected hundreds of thousands of deaths.

Similarly, it has been argued that the bomb cut the duration of the war down significantly and forced the Japanese emperor to decide that maintaining the war was not an option. By ending the war more quickly, the argument goes, less Japanese died than would have in a drawn-out invasion.

“I think that the bombs were believed at the time to be necessary. as General [George] Marshall, who was head of the US military during the war said after the war, ‘we didn’t want to have to invade Japan,’” Richard Rhodes, an American historian, journalist and author who won a Pulitzer Prize for his book “The Making of the Atomic Bomb,” told RT.

All of that, of course, is completely inane.

ReplyDeleteEvery stick and particle of the still-obscenely-huge US nuclear arsenal is, was, and always will be intended for nothing but death, and that is equally true of every stick and particle of the equally still-obscenely-huge Russian nuclear arsenal, every stick and particle of the absolutely unaccountably enormous Israeli nuclear arsenal, and every stick and particle of any other nuclear arsenal that may yet be amassed, for we all understand that the mad amassing and storing and maintaining of nuclear arsenals -- whether these be "meaner and cleaner" (yeah) or meanier and dirtier, whichever the most advanced and arrogant "research" of the moment may command -- will go roaring on as long as there's profit to turned, by the ever more vast and extensive military industrial complex (as Ike called it, forgetting he ought to have said academic scientific greedhead corporate global military industrial complex), and until...

But no. Only kidding. Pay no mind. This is an entertainment medium, yeah? Let's just go out and throw the kids in the car and grab some some of that serious drought-and-wildfire-laced summer fun, while it lasts. And buy now!!

My bad, I had Pete Seeger being 90 when he sang Hikmet's Hiroshima lyric on the clip, in fact he was then 94, and had a bit less than six months to live.

ReplyDelete94, an age not noted for kidding around.

Any of us should be so lucky as to know what that's like.

I'm currently regarding next year as a mythic improbability.

This country has never had a poet of the heartfulness, generosity, humour and stubborn political intelligence of Hikmet -- the most beloved poet of his land, but unable by cause of conscience to stay out of prison there, before finally fleeing for good to Moscow.

The closest thing we've had to Hikmet, it may be, that is, a true populist among bearers of song to the people, and widely beloved for it, was Pete Seeger (also, by the way, once a Communist, and never all that apologetitc about it).

Two of my favourites from this grand poet:

ReplyDeleteNâzim Hikmet Ran: Two Poems