Portrait of Dr. Johannes Cuspinian (detail): Lucas Cranach the Elder, c. 1502 (Oskar Reinhart Collection, Winterthur)

I misbehaved in the cosmos yesterday.

I lived around the clock without questions, without surprise.

I performed daily tasks

as if only that were required.

Inhale, exhale, right foot, left, obligations,

not a thought beyond

getting there and getting back.

getting there and getting back.

The world might have been taken for bedlam,

but I took it just for daily use.

No whats -- no what fors --

and why on earth it is --

and how come it needs so many moving parts.

and how come it needs so many moving parts.

I was like a nail stuck only halfway in the wall

or

(comparison I couldn’t find).

(comparison I couldn’t find).

One change happened after another

even in a twinkling’s narrow span.

Yesterday’s bread was sliced otherwise

by a hand a day younger at a younger table.

Clouds like never before and rain like never,

since it fell after all in different drops.

The world rotated on its axis,

but in a space abandoned forever.

This took a good 24 hours.

1,440 minutes of opportunity.

86,400 seconds for inspection.

86,400 seconds for inspection.

The cosmic savoir vivre

may keep silent on our subject,

still it makes a few demands:

occasional attention, one or two of Pascal’s thoughts,

and amazed participation in a game

with rules unknown.

Wislawa Szymborska (1923-2012): Distraction, from Colon (2005), translated by Clare Cavanagh in MAP: Collected and Last Poems, 2015

still it makes a few demands:

occasional attention, one or two of Pascal’s thoughts,

and amazed participation in a game

with rules unknown.

Wislawa Szymborska (1923-2012): Distraction, from Colon (2005), translated by Clare Cavanagh in MAP: Collected and Last Poems, 2015

Portrait of Dr. Johannes Cuspinian: Lucas Cranach the Elder, c. 1502, oil on wood, 59 x 45 cm (Oskar Reinhart Collection, Winterthur)

Yes, but what time is it? These four clock faces in the new Bristol bus station have one hand each. The furthest right moves fast enough to be a second hand... I'm not sure about the rest. They don't seem to be pointing in appropriate directions for the time (just after five past two).: photo by Rob Brewer, 3 December 2005

Sundial on the steeple of the parish church Saint Nicholas at Liesing, municipality Lesachtal, district Hermagor, Carinthia/Austria: photo by Johann Jaritz, 23 May 2007

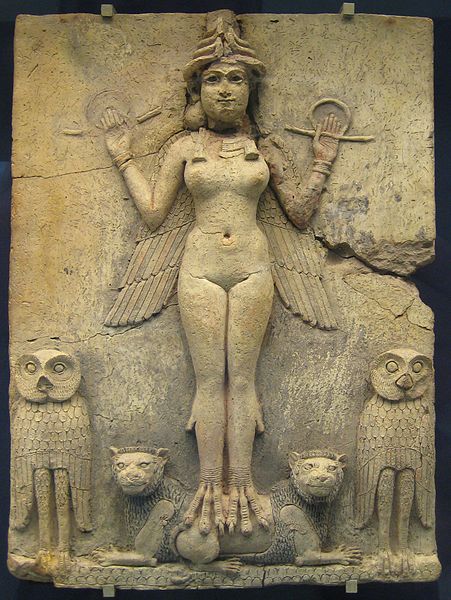

Hindu Time Goddess Kali with written invitation for Kalipuja (festival), near Kolkata. To left, an election mural of the Indian Communist Party of India (Marxist): photo by Christina Kundu, 23 May 2005

Listen Fates,

who sit nearest of gods to the throne of Zeus, and weave with shuttles

of adamant, inescapable devices for councels of every kind beyond

counting, Aisa, Clotho and Lachesis, fine-armed daughters of Night,

hearken to our prayers, all-terrible goddesses, of sky and earth.

Pindar: Fragmenta Chorica Adespota, 5

Now if it is not the causal connections which we are concerned with, then the activities of the mind lie open before us. And when we are worried about the nature of thinking, the puzzlement which we wrongly interpret to be one about the nature of a medium is a puzzlement caused by the mystifying use of our language. This kind of mistake recurs again and again in philosophy; e.g. when we are puzzled about the nature of time, when time seems to us a queer thing. We are most strongly tempted to think that here are things hidden, something we can see from the outside but which we can't look into. And yet nothing of the sort is the case. It is not new facts about time which we want to know. All the facts that concern us lie open before us. But it is the use of the substantive "time" which mystifies us. If we look into the grammar of that word, we shall feel that it is no less astounding that man should have conceived of a deity of time than it would be to conceive of a deity of negation or disjunction.

Ludwig Wittgenstein: from The Blue Book (1930s Cambridge lecture notes as circulated by students), 1958

Ludwig Wittgenstein: from Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus, 1921

Pindar: Fragmenta Chorica Adespota, 5

Now if it is not the causal connections which we are concerned with, then the activities of the mind lie open before us. And when we are worried about the nature of thinking, the puzzlement which we wrongly interpret to be one about the nature of a medium is a puzzlement caused by the mystifying use of our language. This kind of mistake recurs again and again in philosophy; e.g. when we are puzzled about the nature of time, when time seems to us a queer thing. We are most strongly tempted to think that here are things hidden, something we can see from the outside but which we can't look into. And yet nothing of the sort is the case. It is not new facts about time which we want to know. All the facts that concern us lie open before us. But it is the use of the substantive "time" which mystifies us. If we look into the grammar of that word, we shall feel that it is no less astounding that man should have conceived of a deity of time than it would be to conceive of a deity of negation or disjunction.

Ludwig Wittgenstein: from The Blue Book (1930s Cambridge lecture notes as circulated by students), 1958

Death is not an event in life: we do not live to

experience

death.

If we take eternity to mean not infinite temporal duration but timelessness, then eternal life belongs to those who live in the present.

Our life has no end in just the way our visual field has no

limits.

If we take eternity to mean not infinite temporal duration but timelessness, then eternal life belongs to those who live in the present.

Ludwig Wittgenstein: from Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus, 1921

The Three Fates, called by Hesiod the Daughters of the Night. Atropos or Aisa (left) was the oldest of the Three Fates, and was known as the "inflexible" or "inevitable." It was Atropos who chose the mechanism of death and ended the life of each mortal by cutting their thread with her "abhorred shears." She worked along with her two sisters, Clotho, who spun the thread, and Lachesis, who measured the length: Cecchino del Salviati, 1550 (Galleria Palatino, Pizzi Palace, Florence)

Atropos (Ἄτροπος, "inexorable" or "inevitable", literally "unturning, without turn"), in Greek myth one of the three Moirai, goddesses of Fate: Asmus Jacob Carsten (model), 1794 (Städelsches Kunstinstitut, Frankfurt)

The

Triumph of Death, or The Three Fates. The Three Fates, Clotho (right),

Lachesis (centre) and Atropos (left), who spin, draw out and snip the thread of Life,

represent Death,

triumphing over the fallen body of Chastity, in this tapestry

illustrating the third subject in

Petrarch's poem The Triumphs (first, Love triumphs; then Love is

overcome by Chastity, Chastity by Death, Death by Fame, Fame by Time and

Time by Eternity): Flemish tapestry, probably Brussels, c. 1510-1520; image by Wilhem Meis, 5 December 2004

The Three Moirai (Greek "apportioners", l. to r. Clotho, Atropos, Lachesis), tomb of Prince Alexander von Mark: Johann Gottfried Schaddow, 1788-1789; image by Andreas Praefcke, February 2006 (Alte Nationalgalerie, Berlin)

Allegory of Melancholy: Lucas Cranach the Elder, 1532, oil and tempera on wood, 77 x 56 cm (Musée d'Unterlinden, Colmar)

Allegory of Melancholy: Lucas Cranach the Elder, 1528, oil and tempera on wood, 113 x 72 cm (National Gallery of Scotland)

Portrait of Anna Cuspinian: Lucas Cranach the Elder, c. 1502, oil on wood, 59 x 45 cm (Oskar Reinhart Collection, Winterthur)

Portrait of Anna Cuspinian (detail): Lucas Cranach the Elder, c. 1502 (Oskar Reinhart Collection, Winterthur)

Portrait of Anna Cuspinian (detail): Lucas Cranach the Elder, c. 1502 (Oskar Reinhart Collection, Winterthur)

Landscape (fragment): Lucas Cranach the Elder, 1525-30, oil and tempera on wood, 43 x 28 cm (Private collection)

I love Szymborska! Great post.

ReplyDeletelove the poem and the quotes ...!!

ReplyDeleteis nice

ReplyDeleteJust what the doctor ordered and it's not our usual dose of omphaloskepsis.

ReplyDeleteLovely to be reminded this wonderful poet is not just a private taste -- many thanks to all Szymborska's brilliant testifying friends!

ReplyDeleteIn response, a bit more of a good thing, this one from a half century earlier on (how many poets have that kind of staying power?):

Wislawa Szymborska: Tarsier