A Foggy Day in London Town. South Bank, London: photo by Becky Frances, 30 March 2017

A Foggy Day in London Town. South Bank, London: photo by Becky Frances, 30 March 2017

A Foggy Day in London Town. South Bank, London: photo by Becky Frances, 30 March 2017

City workers cross the Millennium Bridge over the River Thames on a foggy morning in London: photo by Toby Melville/Reuters, 2 November 2015

City workers cross the Millennium Bridge over the River Thames on a foggy morning in London: photo by Toby Melville/Reuters, 2 November 2015

A seagull flies past Westminster Bridge during a foggy day in central London today. Airports across Britain suffered disruption on Monday as heavy fog led to delays and cancellations for a second day. Flights to and from London airports were being affected, while foggy conditions in the capital and across Europe were causing problems to airports around the country: photo by Stefan Wermuth/Reuters, 2 November 2015

A seagull flies past Westminster Bridge during a foggy day in central London today. Airports across Britain suffered disruption on Monday as heavy fog led to delays and cancellations for a second day. Flights to and from London airports were being affected, while foggy conditions in the capital and across Europe were causing problems to airports around the country: photo by Stefan Wermuth/Reuters, 2 November 2015

William Wordsworth: A Crowd of Strangers (1805)

London Nocturne in Grey and Gold: Snow in Chelsea: James Abbot McNeill Whistler, 1876 (Fogg Museum, Cambridge, Massachusetts)

O Friend! one feeling was there which belong'd

To this great City, by exclusive right;

How often in the overflowing Streets,

Have I gone forward with the Crowd, and said

Unto myself, the face of every one

That passes by me is a mystery.

To this great City, by exclusive right;

How often in the overflowing Streets,

Have I gone forward with the Crowd, and said

Unto myself, the face of every one

That passes by me is a mystery.

Thus have I look'd, nor ceas'd to look, oppress'd

By thoughts of what, and whither, when and how,

Until the shapes before my eyes became

A second-sight procession, such as glides

Over still mountains, or appears in dreams;

And all the ballast of familiar life,

The present, and the past; hope, fear; all stays,

All laws of acting, thinking, speaking man

Until the shapes before my eyes became

A second-sight procession, such as glides

Over still mountains, or appears in dreams;

And all the ballast of familiar life,

The present, and the past; hope, fear; all stays,

All laws of acting, thinking, speaking man

Went from me, neither knowing me, nor known.

And once, far-travell'd in such mood, beyond

The reach of common indications, lost

Amid the moving pageant, 'twas my chance

Abruptly to be smitten with the view

Of a blind Beggar, who, with upright face,

Stood propp'd against a Wall, upon his Chest

Wearing a written paper, to explain

The story of the Man, and who he was.

My mind did at this spectacle turn round

As with the might of waters, and it seem'd

To me that in this Label was a type,

Or emblem, of the utmost that we know

Both of ourselves and of the universe;

And, on the shape of that unmoving man,

His fixèd face and sightless eyes, I looked,

As if admonish'd from another world.

The reach of common indications, lost

Amid the moving pageant, 'twas my chance

Abruptly to be smitten with the view

Of a blind Beggar, who, with upright face,

Stood propp'd against a Wall, upon his Chest

Wearing a written paper, to explain

The story of the Man, and who he was.

My mind did at this spectacle turn round

As with the might of waters, and it seem'd

To me that in this Label was a type,

Or emblem, of the utmost that we know

Both of ourselves and of the universe;

And, on the shape of that unmoving man,

His fixèd face and sightless eyes, I looked,

As if admonish'd from another world.

William Wordsworth (1770-1850): from The Prelude, Book VII (Residence in London), 1805

St. Mary le Strand, London: artist unknown, early 19th c.

Wordsworth saw strangeness, a loss of connection, not at first in social but in perceptual ways: a failure of identity in the crowd of others which worked back to a loss of identity in the self and then, in these ways, in society itself, its overcoming and replacement by a procession of images...

What is evident here is the rapid transition from the mundane fact that the people in the crowd are unknown to the observer -- though we now forget what a novel experience that must in any case have been to people used to customary small settlements -- to the now characteristic interpretation of 'strangeness' as 'mystery'. Ordinary modes of perceiving others are seen as overborne by the collapse of normal relationships and their laws: a loss of 'the ballast of familiar life'. Other people are then seen as if in 'second sight' or, crucially, as in dreams: a major point of reference for many subsequent modern artistic techniques.

What is evident here is the rapid transition from the mundane fact that the people in the crowd are unknown to the observer -- though we now forget what a novel experience that must in any case have been to people used to customary small settlements -- to the now characteristic interpretation of 'strangeness' as 'mystery'. Ordinary modes of perceiving others are seen as overborne by the collapse of normal relationships and their laws: a loss of 'the ballast of familiar life'. Other people are then seen as if in 'second sight' or, crucially, as in dreams: a major point of reference for many subsequent modern artistic techniques.

-- Raymond Williams

The Last Supper. Preston.: photo by Becky Frances, 12 January 2017

The Last Supper. Preston.: photo by Becky Frances, 12 January 2017

The Last Supper. Preston.: photo by Becky Frances, 12 January 2017

[Untitled]: photo by Gareth Bragdon, 9 August 2016

[Untitled]: photo by Gareth Bragdon, 9 August 2016

[Untitled]: photo by Gareth Bragdon, 9 August 2016

[Untitled, Belgrade]: photo by Aleksandra Perovic, 19 April 2017

[Untitled, Belgrade]: photo by Aleksandra Perovic, 19 April 2017

[Untitled, Belgrade]: photo by Aleksandra Perovic, 19 April 2017

Head in the Clouds. Soho, London.: photo by Becky Frances, 6 February 2017

Head in the Clouds. Soho, London.: photo by Becky Frances, 6 February 2017

Head in the Clouds. Soho, London.: photo by Becky Frances, 6 February 2017

Cobblestones in the Rain. Soho, London: photo by Becky Frances, 17 February 2016

Cobblestones in the Rain. Soho, London.: photo by Becky Frances, 17 February 2016

Cobblestones in the Rain. Soho, London.: photo by Becky Frances, 17 February 2016

Anonymous. Brick Lane, London: photo by Becky Frances, 23 October 2016

Anonymous. Brick Lane, London: photo by Becky Frances, 23 October 2016

Anonymous. Brick Lane, London: photo by Becky Frances, 23 October 2016

Paperface. Blackpool.: photo by Becky Frances, 13 January 2017

Paperface. Blackpool.: photo by Becky Frances, 13 January 2017

Paperface. Blackpool.: photo by Becky Frances, 13 January 2017

Light Fingered. Soho, London.: photo by Becky Frances, 30 March 2017

Light Fingered. Soho, London.: photo by Becky Frances, 30 March 2017

Light Fingered. Soho, London.: photo by Becky Frances, 30 March 2017

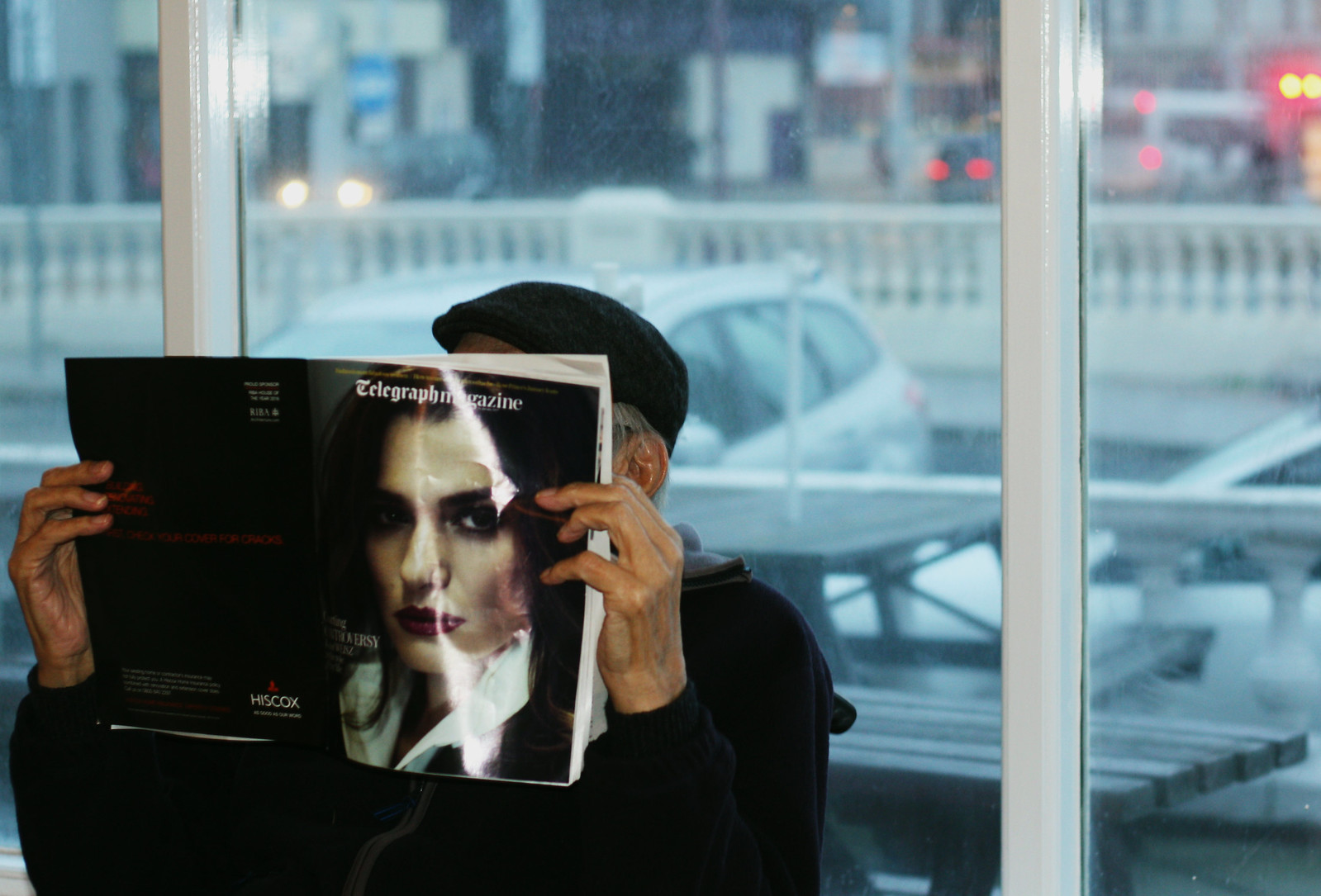

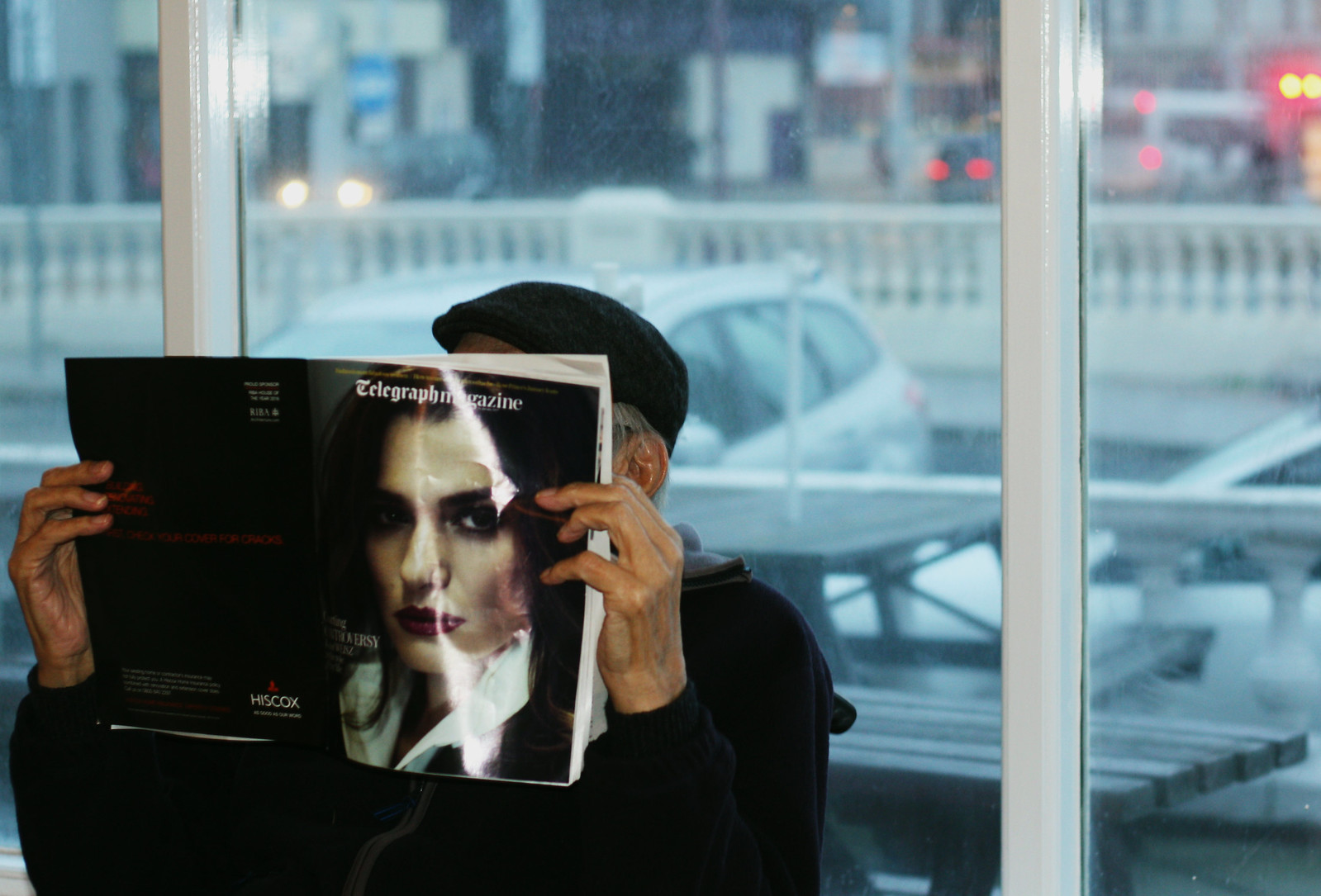

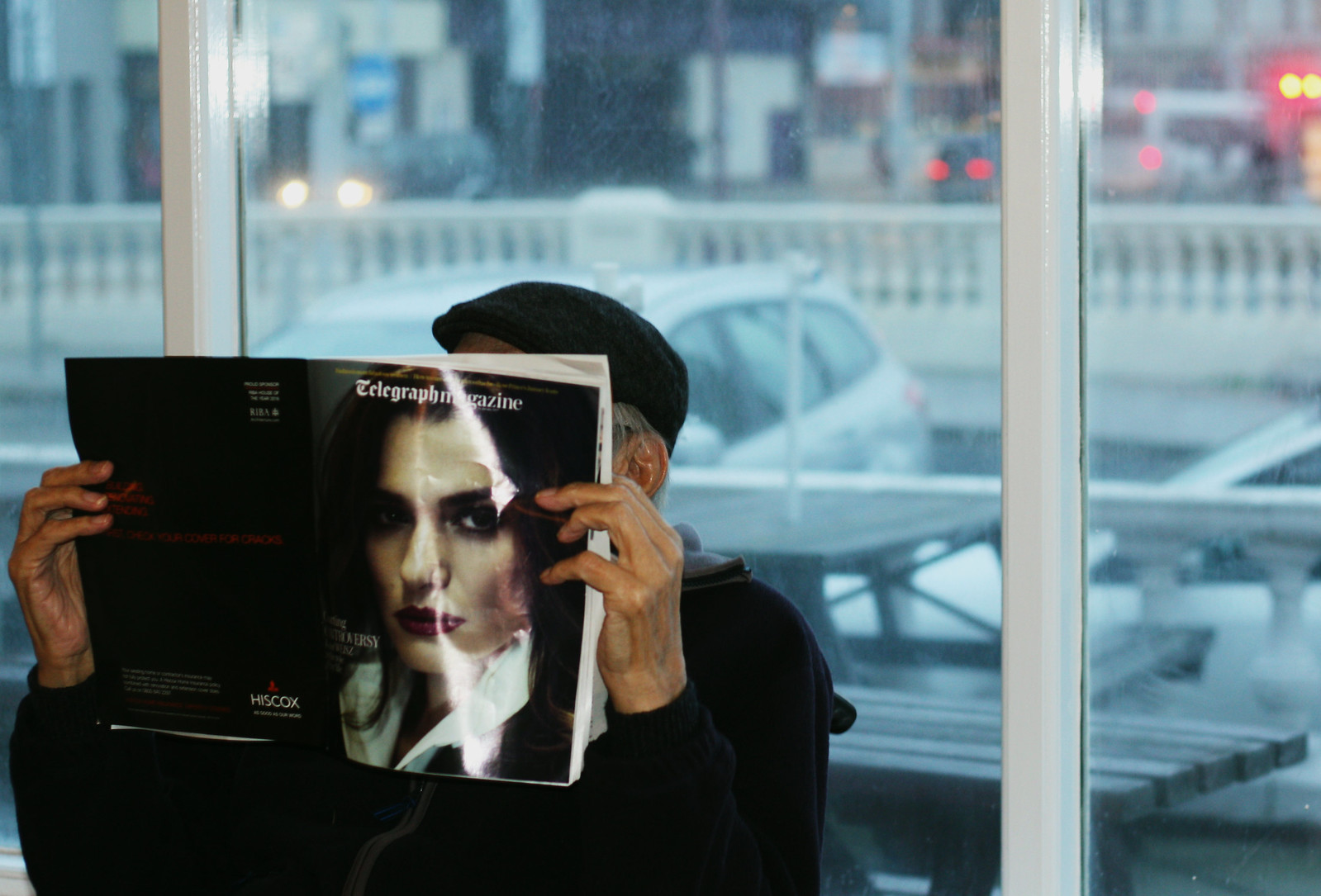

Two Faced. Blackpool.: photo by Becky Frances, 14 January 2017

Two Faced. Blackpool.: photo by Becky Frances, 14 January 2017

Two Faced. Blackpool.: photo by Becky Frances, 14 January 2017

Cafe Stories. Blackpool.: photo by Becky Frances, 13 January 2017

Cafe Stories. Blackpool.: photo by Becky Frances, 13 January 2017

Cafe Stories. Blackpool.: photo by Becky Frances, 13 January 2017

Shibuya shopping district, Tokyo, night: photo by

Bantosh, 2006

Tokyo Ginza in night rain: photo by Thomas Birke, 2008

from Dal Tokyo (detail): Gary Panter, 1983; image via Fantagraphics Books, 2012

from Dal Tokyo (detail): Gary Panter, 1983; image via Fantagraphics Books, 2012

shinjuku, tokyo: photo by wire_paladinSF, 10 April 2014

from Dal Tokyo (detail): Gary Panter, 1984; image via Fantagraphics Books, 2012

Tokyo Invasion: "All your base are belong to US". The Empire sent three Stormtroopers to invade Tokyo. One went off dancing and the other two decided to take some time off instead, seeing the sights at Akihabara, Shibuya, Asakusa and more.: photo by Danny Choo, 25 January 2011

From Shoreditch Wildife: photo by Dougie Wallace, 2014

.

. From Shoreditch Wildife: photo by Dougie Wallace, 2014

Friedrich Engels: The Great Towns (1845)

A town, such as London, where a man may wander for hours together without

reaching the beginning of the end, without meeting the slightest hint which

could lead to the inference that there is open country within reach, is a

strange thing.

This colossal centralisation, this heaping together of two and a

half millions of human beings at one point, has multiplied the power of this

two and a half millions a hundredfold; has raised London to the commercial

capital of the world, created the giant docks and assembled the thousand

vessels that continually cover the Thames.

I know nothing more imposing than

the view which the Thames offers during the ascent from the sea to London

Bridge.

The masses of buildings, the wharves on both sides, especially from

Woolwich upwards, the countless ships along both shores, crowding ever closer

and closer together, until, at last, only a narrow passage remains in the

middle of the river, a passage through which hundreds of steamers shoot by one

another; all this is so vast, so impressive, that a man cannot collect himself,

but is lost in the marvel of England's greatness before he sets foot upon

English soil.

Canary Wharf, London, viewed from Shadwell: photo by Dave Pape, 13 June 2007

But the sacrifices which all this has cost become apparent later.

After roaming the streets of the capital a day or two, making headway with difficulty through the human turmoil and the endless lines of vehicles, after visiting the slums of the metropolis, one realises for the first time that these Londoners have been forced to sacrifice the best qualities of their human nature, to bring to pass all the marvels of civilisation which crowd their city; that a hundred powers which slumbered within them have remained inactive, have been suppressed in order that a few might be developed more fully and multiply through union with those of others.

The very turmoil of the streets has something repulsive, something against which human nature rebels.

The hundreds

of thousands of all classes and ranks crowding past each other, are they not

all human beings with the same qualities and powers, and with the same interest

in being happy?

And have they not, in the end, to seek happiness in the same

way, by the same means?

And still they crowd by one another as though they had

nothing in common, nothing to do with one another, and their only agreement is

the tacit one, that each keep to his own side of the pavement, so as not to

delay the opposing streams of the crowd, while it occurs to no man to honour

another with so much as a glance.

The brutal indifference, the unfeeling

isolation of each in his private interest, becomes the more repellent and

offensive, the more these individuals are crowded together, within a limited

space.

And, however much one may be aware that this isolation of the

individual, this narrow self-seeking, is the fundamental principle of our

society everywhere, it is nowhere so shamelessly barefaced, so self-conscious

as just here in the crowding of the great city.

The dissolution of mankind into

monads, of which each one has a separate principle, the world of atoms, is here

carried out to its utmost extreme.

Hence it comes, too, that the social war, the war of each against all, is

here openly declared.

Just as in Stirner's recent book [The Ego and Its Own],

people regard each other only as useful objects; each exploits the other, and

the end of it all is that the stronger treads the weaker under foot; and that

the powerful few, the capitalists, seize everything for themselves, while to

the weak many, the poor, scarcely a bare existence remains.

What is true of London, is true of Manchester, Birmingham, Leeds, is true of

all great towns.

Everywhere barbarous indifference, hard egotism on one hand,

and nameless misery on the other, everywhere social warfare, every man's house

in a state of siege, everywhere reciprocal plundering under the protection of

the law, and all so shameless, so openly avowed that one shrinks before the

consequences of our social state as they manifest themselves here undisguised,

and can only wonder that the whole crazy fabric still hangs together.

Since capital, the direct or indirect control of the means of subsistence

and production, is the weapon with which this social warfare is carried on, it

is clear that all the disadvantages of such a state must fall upon the poor.

For him no man has the slightest concern. Cast into the whirlpool, he must

struggle through as well as he can.

If he is so happy as to find work, i.e., if

the bourgeoisie does him the favour to enrich itself by means of him, wages

await him which scarcely suffice to keep body and soul together; if he can get

no work he may steal, if he is not afraid of the police, or starve, in which

case the police will take care that he does so in a quiet and inoffensive

manner.

During my residence in England, at least twenty or thirty persons have died of simple starvation under the most revolting circumstances, and a jury has rarely been found possessed of the courage to speak the plain truth in the matter.

Let the testimony of the witnesses be never so clear and unequivocal,

the bourgeoisie, from which the jury is selected, always finds some backdoor

through which to escape the frightful verdict, death from starvation.

The bourgeoisie dare not speak the truth in these cases, for it would speak its own

condemnation.

But indirectly, far more than directly, many have died of

starvation, where long-continued want of proper nourishment has called forth

fatal illness, when it has produced such debility that causes which might

otherwise have remained inoperative brought on severe illness and death.

The

English working-men call this "social murder", and accuse our whole society of

perpetrating this crime perpetually. Are they wrong?

True, it is only individuals who starve, but what security has the

working-man that it may not be his turn tomorrow?

Who assures him employment,

who vouches for it that, if for any reason or no reason his lord and master

discharges him tomorrow, he can struggle along with those dependent upon him,

until he may find some one else "to give him bread"?

Who guarantees that

willingness to work shall suffice to obtain work, that uprightness, industry,

thrift, and the rest of the virtues recommended by the bourgeoisie, are really

his road to happiness?

No one. He knows that he has something today and that it

does not depend upon himself whether he shall have something tomorrow.

He knows

that every breeze that blows, every whim of his employer, every bad turn of

trade may hurl him back into the fierce whirlpool from which he has temporarily

saved himself, and in which it is hard and often impossible to keep his head

above water.

He knows that, though he may have the means of living today, it is

very uncertain whether he shall tomorrow.

Friedrich Engels: from Die Lage der arbeitenden Klasse in England (Condition of the Working Class in England), 1844-1845: published in Leipzig, 1845; English translation by Florence Kelley [Wischnewetzky], New York, 1887; London, 1891

La Proximité de la Mer (Borges), Canary Wharf, London: photo by galaad, 4 April 2010

Shanty town, Manila, beside Manila City Jail (seen from Recto LRT Station): photo by Mile Gonzalez, 20 May 2007

Sun sets over the old medina in central Tripoli: photo by Patrick André Perron, 2007

From Shoreditch Wildife: photo by Dougie Wallace, 2014

From Shoreditch Wildife: photo by Dougie Wallace, 2014

[Untitled, Sao Paulo]: photo by Gustavo Gomes, 9 November 2013

[Untitled, Sao Paulo]: photo by Gustavo Gomes, 9 November 2013

[Untitled, Sao Paulo]: photo by Gustavo Gomes, 9 November 2013

[Untitled, Sao Paulo]: photo by Gustavo Gomes, 9 November 2013

[Untitled, Sao Paulo]: photo by Gustavo Gomes, 9 November 2013

[Untitled, Sao Paulo]: photo by Gustavo Gomes, 9 November 2013

Tremendous. Engels and Wordsworth. And crowds and faces.

ReplyDelete

ReplyDeleteThank you, Hilton. Who knew until now that Freddie and Willy were so close, there, in the enveloping historical fog on Millennium Bridge.

TC: Maybe just waking up, but this one truly beyond the pale. Thanks.

ReplyDelete