.

UN

says 370,000 Rohingya flee Myanmar for Bangladesh #AFP Picture taken

at the Bangladeshi side of Naf river in Teknaf. Photo @uz_munir: image via Aurelia BAILLY @AureliaBAILLY, 13 September 2017

My god, this shot of Rohingya refugees watching their houses burn across the border in Myanmar (Masfiqur Sohan/NurPhoto): image via pourmecoffee @pourmecoffee, 12 September 2017

Their villages burning in the distance behind them

Global split over Rohingya crisis as China backs Myanmar crackdown #AFP Picture taken near the Bangladeshi town of Teknaf. Photo @uz_munir: image via Aurelia BAILLY @AureliaBAILLY, 12 September 2017

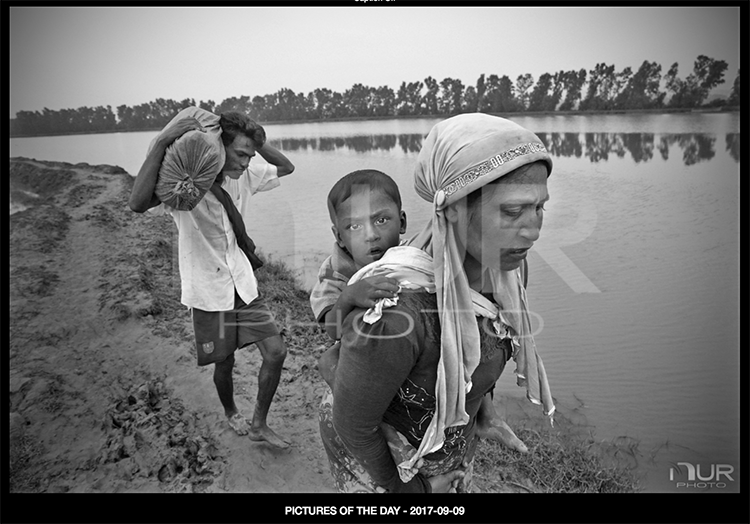

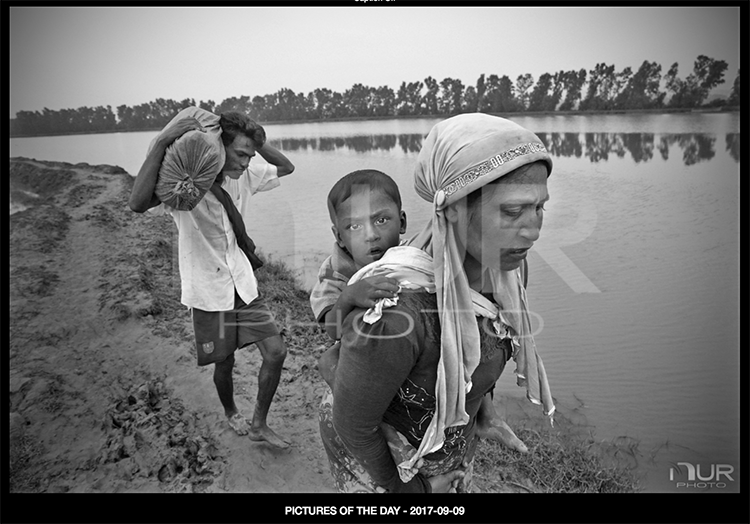

Nowhere else to go #Rohingya #refugees try their luck at #Bangladesh border.: image via NurPhoto @NurPhoto, 7 September 2017

#Rohingya refugees cross over to #Bangladesh from #Myanmar.: image via NurPhoto @NurPhoto, 11 September 2017

#Monsoon rains in South Asia put 1/3rd #Bangladesh under water. #climate: image via Nur Photo @NurPhoto, 21 August 2017

#Rohingya wait at #Bangladesh border after fleeing #Myanmar.: image via Nur Photo @NurPhoto, 2 September 2017

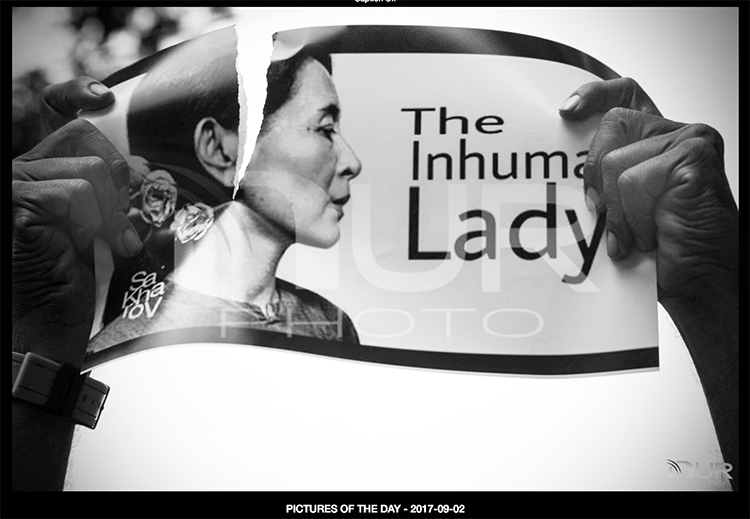

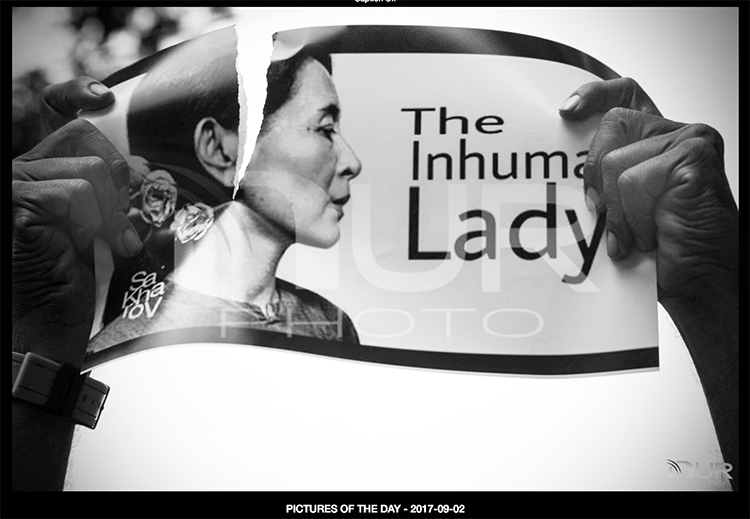

Rally against #Rohingya persecutions in #Jakarta.: image via Nur Photo @NurPhoto, 4 September 2017

Nowhere else to go #Rohingya #refugees try their luck at #Bangladesh border.: image via NurPhoto @NurPhoto, 7 September 2017

#Rohingya refugees cross over to #Bangladesh from #Myanmar.: image via NurPhoto @NurPhoto, 11 September 2017

Rohingya refugees wait for food to be distributed by local organisations

near Balukhali makeshift refugee camp in Cox's Bazar, Bangladesh,

September 13, 2017.: photo by Danish Siddiqui/Reuters, 13 September 2017

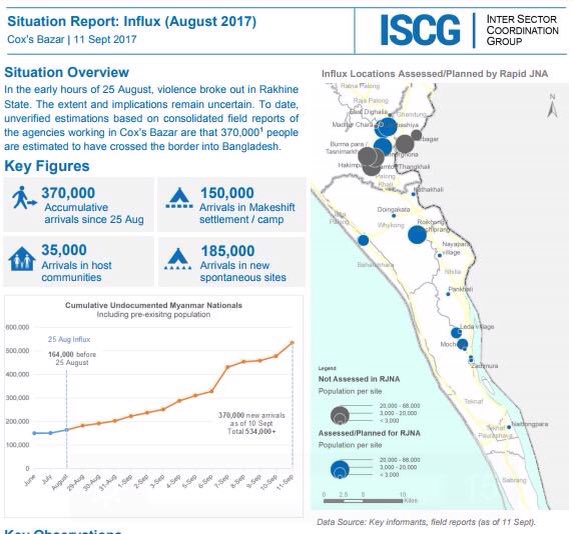

U.N. seeks 'massive' aid boost amid Rohingya 'emergency within an emergency': Krishna N. Das, Reuters, 13 September 2017

KUTUPALONG

CAMP, Bangladesh (Reuters) - Aid agencies have to step up operations

“massively” in response to the arrival in Bangladesh of about 400,000

refugees fleeing violence in Myanmar, and the amount of money needed to

help them has risen sharply, a senior U.N. official said on Wednesday.

The

exodus of Muslim Rohingya to Bangladesh began on Aug. 25 after Rohingya

militants attacked about 30 police posts and an army camp. The attacks

triggered a sweeping military counter-offensive by security forces in

Buddhist-majority Myanmar which the U.N. rights agency said was a

“textbook example of ethnic cleansing”.

“We

will all have to ramp up our response massively, from food to shelter,”

George William Okoth-Obbo, assistant high commissioner for operations at

the U.N. refugee agency, told Reuters during a visit to the Kutupalong

refugee camp in Bangladesh.

The United Nations

said on Tuesday 370,000 people had crossed into Bangladesh but

Okoth-Obbo estimated the figure was now 400,000. He declined to

speculate on how many more might come.

Bangladesh

was already home to about 400,000 Rohingya, who fled earlier conflict

in Myanmar including a similar security crackdown in western Myanmar’s

Rakhine state in response to militant attacks in October.

Many of the new arrivals are hungry and sick, without shelter or clean water in the middle of the rainy season.

“We

have an emergency within an emergency with conditions in existing

camps,” he said, pointing to a mud-clogged road in the camp.

Last

week, the United Nations appealed for $77 million to cope with the

crisis but Okoth-Obbo said that would not now be enough.

“The

appeal that was issued of $77 million on behalf of the aid agencies was

based on the situation as it was roughly about two weeks ago,” he said.

“There were only 100,000 people then. We are already four times that figure now. The funds need clearly is going to continue.”

He declined to say how much he thought was needed.

He

also declined to say if he thought aid agencies were getting proper

access to the conflict zone in Myanmar, though he said it was important

to ensure that people were safe where they were.

“Of course, also that access is provided to all the responders to provide humanitarian assistance,” he added.

Myanmar

has restricted most aid agency access to the north of Rakhine. Some

officials have accused aid agencies of supporting the insurgents.

Okoth-Obbo

said he agreed with the Bangladeshi position that the most important

solution was for the refugees to be able to return home in safety.

Bangladeshi

Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina said on Tuesday the refugees would all

have to go home and Myanmar should set up safe zones to enable them to

do so.

“Under difficult circumstances this country has kept its borders open,” Okoth-Obbo said of Bangladesh.

“All of us should support that and ensure that the response is strong.”

0004899e Rohingya refugees walk through water after crossing border by boat through the Naf River in Teknaf, Bangladesh, September 7, 2017. (Photo by Mohammad Ponir Hossain/Reuters): image by Jean Bosco SIBOMANA, 11 September 2017

0004899e Rohingya refugees walk through water after crossing border by boat through the Naf River in Teknaf, Bangladesh, September 7, 2017. (Photo by Mohammad Ponir Hossain/Reuters): image by Jean Bosco SIBOMANA, 11 September 2017

0004899e Rohingya refugees walk through water after crossing border by boat through the Naf River in Teknaf, Bangladesh, September 7, 2017. (Photo by Mohammad Ponir Hossain/Reuters): image by Jean Bosco SIBOMANA, 11 September 2017

0004899e Rohingya refugees walk through water after crossing border by boat through the Naf River in Teknaf, Bangladesh, September 7, 2017. (Photo by Mohammad Ponir Hossain/Reuters): image by Jean Bosco SIBOMANA, 11 September 2017

0004899e Rohingya refugees walk through water after crossing border by boat through the Naf River in Teknaf, Bangladesh, September 7, 2017. (Photo by Mohammad Ponir Hossain/Reuters): image by Jean Bosco SIBOMANA, 11 September 2017

0004899e Rohingya refugees walk through water after crossing border by boat through the Naf River in Teknaf, Bangladesh, September 7, 2017. (Photo by Mohammad Ponir Hossain/Reuters): image by Jean Bosco SIBOMANA, 11 September 2017

Myanmar faces mounting pressure over Rohingya refugee exodus: Krishna N. Das, Reuters, 11 September 2017

COX‘S

BAZAR, Bangladesh (Reuters) - Pressure mounted on Myanmar on Tuesday to

end violence that has sent about 370,000 Rohingya Muslims fleeing to

Bangladesh, with the United States calling for protection of civilians

and Bangladesh urging safe zones to enable refugees to go home.

But China, which competes for influence in its southern neighbor with the United States, said it backed Myanmar’s efforts to safeguard “development and stability”.

The government of Buddhist-majority Myanmar says its security forces are fighting Rohingya militants behind a surge of violence in Rakhine state that began on Aug. 25, and they are doing all they can to avoid harming civilians.

The government says about 400 people have been killed in the fighting, the latest in the western state.

The top U.N. human rights official denounced Myanmar on Monday for conducting a “cruel military operation” against Rohingya, branding it “a textbook example of ethnic cleansing”.

The United States said the violent displacement of the Rohingya showed Myanmar’s security forces were not protecting civilians. Washington has been a staunch supporter of Myanmar’s transition from decades of harsh military rule that is being led by Nobel peace laureate Aung San Suu Kyi.

“We call on Burmese security authorities to respect the rule of law, stop the violence, and end the displacement of civilians from all communities,” the White House said in a statement.

Myanmar government spokesmen were not immediately available for comment but the foreign ministry said shortly before the U.S. statement was issued that Myanmar was also concerned about the suffering. Its forces were carrying out their legitimate duty to restore order in response to acts of extremism.

“The government of Myanmar fully shares the concern of the international community regarding the displacement and suffering of all communities affected by the latest escalation of violence ignited by the acts of terrorism,” the ministry said in a statement.

Myanmar’s government regards Rohingya as illegal migrants from Bangladesh and denies them citizenship, even though many Rohingya families have lived there for generations.

But China, which competes for influence in its southern neighbor with the United States, said it backed Myanmar’s efforts to safeguard “development and stability”.

The government of Buddhist-majority Myanmar says its security forces are fighting Rohingya militants behind a surge of violence in Rakhine state that began on Aug. 25, and they are doing all they can to avoid harming civilians.

The government says about 400 people have been killed in the fighting, the latest in the western state.

The top U.N. human rights official denounced Myanmar on Monday for conducting a “cruel military operation” against Rohingya, branding it “a textbook example of ethnic cleansing”.

The United States said the violent displacement of the Rohingya showed Myanmar’s security forces were not protecting civilians. Washington has been a staunch supporter of Myanmar’s transition from decades of harsh military rule that is being led by Nobel peace laureate Aung San Suu Kyi.

“We call on Burmese security authorities to respect the rule of law, stop the violence, and end the displacement of civilians from all communities,” the White House said in a statement.

Myanmar government spokesmen were not immediately available for comment but the foreign ministry said shortly before the U.S. statement was issued that Myanmar was also concerned about the suffering. Its forces were carrying out their legitimate duty to restore order in response to acts of extremism.

“The government of Myanmar fully shares the concern of the international community regarding the displacement and suffering of all communities affected by the latest escalation of violence ignited by the acts of terrorism,” the ministry said in a statement.

Myanmar’s government regards Rohingya as illegal migrants from Bangladesh and denies them citizenship, even though many Rohingya families have lived there for generations.

Attacks

by a Rohingya insurgent group, the Arakan Rohingya Salvation Army

(ARSA), on police posts and an army base in the north of Rakhine on Aug.

25 provoked the military counter-offensive that refugees say is aimed

at pushing Rohingya out of the country.

A similar but smaller

wave of attacks by the same insurgents last October also sparked what

critics called a heavy-handed response by the security forces that sent

87,000 Rohingya fleeing to Bangladesh.

Reports from refugees and

rights groups paint a picture of widespread attacks on Rohingya villages

in the north of Rakhine by the security forces and ethnic Rakhine

Buddhists, who have put numerous Muslim villages to the torch.

But

Myanmar authorities have denied that the security forces, or Buddhist

civilians, have been setting the fires, instead blaming the insurgents.

Nearly 30,000 Buddhist villagers have also been displaced, they say.

0004899a0 Rohingya refugees wait for boat to cross a canal after crossing the border through the Naf river in Teknaf, Bangladesh, September 7, 2017. (Photo by Mohammad Ponir Hossain/Reuters): image by Jean Bosco SIBOMANA, 11 September 2017

0004899a0 Rohingya refugees wait for boat to cross a canal after crossing the border through the Naf river in Teknaf, Bangladesh, September 7, 2017. (Photo by Mohammad Ponir Hossain/Reuters): image by Jean Bosco SIBOMANA, 11 September 2017

0004899a0 Rohingya refugees wait for boat to cross a canal after crossing

the border through the Naf river in Teknaf, Bangladesh, September 7,

2017. (Photo by Mohammad Ponir Hossain/Reuters): image by Jean Bosco SIBOMANA, 11 September 2017

0004899a0 Rohingya refugees wait for boat to cross a canal after crossing the border through the Naf river in Teknaf, Bangladesh, September 7, 2017. (Photo by Mohammad Ponir Hossain/Reuters): image by Jean Bosco SIBOMANA, 11 September 2017

0004899a0 Rohingya refugees wait for boat to cross a canal after crossing the border through the Naf river in Teknaf, Bangladesh, September 7, 2017. (Photo by Mohammad Ponir Hossain/Reuters): image by Jean Bosco SIBOMANA, 11 September 2017

‘STOP THE VIOLENCE’

The

U.N. Security Council is to meet on Wednesday behind closed doors for

the second time during the crisis since Aug. 25. British U.N. Ambassador

Matthew Rycroft said he hoped there would be a public statement agreed

by the council on the crisis.

“It

is important that the Security Council plays its role in responding,”

said Sweden’s U.N. Ambassador Olof Skoog said on Tuesday. Britain and

Sweden requested the meeting.

However, rights groups slammed the

15-member council for not holding a public meeting. Diplomats have said

China and Russia would likely object to such a move and protect Myanmar

if there was any push for council action to try and end the crisis.

“This

is ethnic cleansing on a large scale it seems, and the Security Council

can’t open its doors and stand in front of the cameras? It’s appalling,

frankly,”

Human Rights Watch U.N. director Louis Charbonneau told

reporters on Tuesday.

Sherine Tadros, head of Amnesty International in New York, said if the council doesn’t act “the price is being paid.”

“The

danger is without some sort of public proclamation by Security Council

members ... the message that you’re sending to the Myanmar government is

deadly, and they will continue to do it,” Tadros told reporters.

The

exodus to Bangladesh shows no sign of slowing with 370,000 the latest

estimate, according to a U.N. refugee agency spokeswoman, up from an

estimate of 313,000 on the weekend.

Bangladesh was already home to about 400,000 Rohingyas.

Many

refugees are hungry and sick, without shelter or clean water in the

middle of the rainy season. The United Nations said 200,000 children

needed urgent support.

Two emergency flights organized by the

U.N. refugee agency arrived in Bangladesh with aid for about 25,000

refugees. More flights are planned with the aim of helping 120,000, a

spokesman said.

Worry is also growing about conditions inside

Rakhine State, with fears a hidden humanitarian crisis may be unfolding.

Myanmar has rejected a ceasefire declared by ARSA to enable the

delivery of aid there, saying it did not negotiate with terrorists.

But Bangladeshi Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina said Myanmar should set up safe zones to enable the refugees to go home.

“Myanmar

will have to take back all Rohingya refugees who entered Bangladesh,”

Hasina said on a visit to the Cox’s Bazar border district where she

distributed aid.

"Myanmar has created the problem and they will

have to solve it,“ she said, adding: ”We want peaceful relations with

our neighbors, but we can’t accept any injustice.

“Stop this violence against innocent people.”

Myanmar has said those who can verify their citizenship can return but most Rohingya are stateless.

In

Beijing, Chinese foreign ministry spokesman Geng Shuang said, “The

international community should support Myanmar in its efforts to

safeguard development and stability.”

Scorched earth: A state-led massacre triggers an exodus of Rohingyas from Myanmar: The Burmese army is burning villages, and raping and killing their inhabitants: The Economist, 9 September 2017

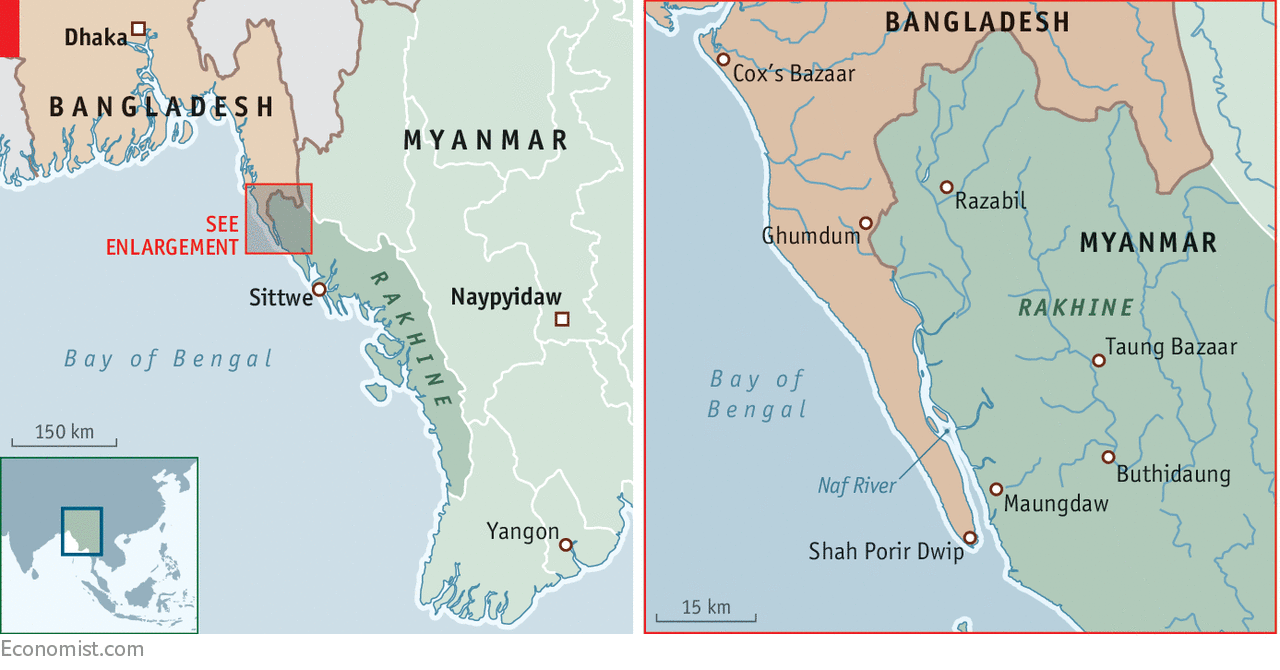

Across

the border, inside Myanmar, columns of smoke can be seen rising at

dawn; each evening dusk reveals the fires at their bases. All week

villages have been burning in northern Rakhine state, home of the

Rohingyas, a persecuted Muslim minority. Refugees have been fleeing to

Bangladesh across rice paddies, along muddy mountain paths and in boats

over the Naf river, which divides the two countries. They are fleeing

systematic violence from the Burmese army and armed mobs of Rakhines,

another local ethnic group. The UN has counted 164,000 who have already

arrived in Bangladesh; many more are thought to be on their way.

At

the end of the Myanmar-Bangladesh Friendship Road, backed against the

border fence near the town of Ghumdum, is a rapidly growing, makeshift

camp holding some 5,000 new refugees. A Bangladeshi border guard points

to a nearby hillock where a fire is raging; he says the Burmese army is

burning down houses. Nurul Islam, a 30-year-old farmer, says he left his

home in Razabil village in Myanmar last week when soldiers opened fire

on villagers and set the houses on fire. Women and men were separated.

Soldiers raped his 13-year-old sister Khadiza; mobs of Rakhines armed

with swords mutilated her body. His father was also killed.

Fatima

Khatun managed to escape her burning village and arrived in Bangladesh

on September 4th with eight members of her family. She says many

children and old people died on the week-long trek through the muddy

monsoon-soaked hills. When she and others crossed a river inside Myanmar

by clinging to bamboo rafts, soldiers opened fire on them. Many more

villagers are hiding in Myanmar or have lost their way, she says.

At

a nearby petrol station, Mohammad Jahangir explains that he has just

arrived from the town of Taung Bazaar after a 13-day march. He is

carrying his 8-year-old son, who cannot walk because of a bullet wound

on his right leg.

Matthew Smith of Fortify Rights, an

NGO, says that based on copious, detailed testimony from many witnesses,

“We can now say with a high level of confidence that state-led security

forces and local armed residents have committed mass killings.” It

looks, says Mr Smith, as if the Burmese army is trying to drive all

Rohingyas out of the country. Fortify Rights has documented many cases

of indiscriminate killing, rape, mutilation and other crimes.

To

the south of Ghumdum, at another border crossing, locals reckon 5,000

refugees have arrived that morning alone. One member of the exhausted

procession is Sawza (who goes by one name), a health worker from the

town of Buthidaung. She left her home on August 25th, the day the

Burmese army went on the rampage in response to attacks by Rohingya

militants that killed 12 policemen. At first, Sawza thought it would be

safe for her family to stay. But when she heard that Zabar Khalimullah, a

wealthy local, had been killed, she decided to flee. Unlike during

another bout of violence last year, affluent landowning Rohingyas are

leaving this time. Sawza says that during her 15-day journey she saw

parents forced to abandon children who were too weak to keep walking and

a man in his 50s who had to leave his 80-year-old father by the

wayside.

Even farther south, on the beach at Shah Porir

Dwip, the southernmost tip of Bangladesh, Roshida Begum climbs out of a

wooden boat with a few belongings and what is left of her family.

Burmese soldiers took away her daughters, who were 16 and 22, she says.

She later found their mutilated bodies. Her husband was also killed.

Farther along the beach is another group of 30 or so Rohingyas, who

spent five days hiding in the hills before crossing to Bangladesh.

Obaida Khatun, the oldest woman in the group, says that three of the

young women with her were raped.

The narrow strip of

Bangladesh that juts into the Bay of Bengal alongside Myanmar already

hosts hundreds of thousands of Rohingya refugees from previous exoduses,

in 1978 and 1991-92. They compete with locals for food, firewood, land

and jobs. It is the poorest part of Bangladesh. Literacy in the region

is 27%. Aid is arriving in dribs and drabs—food, water purifiers,

tarpaulins—but not nearly enough. Among the throngs of refugees looking

for shelter in the area this week was Zainab Begum, whose father was

killed by Burmese soldiers. “Everything has turned to ashes,” she says.

Rohingya exodus puts pressure back on UN rights probe @Sara_Perria: image via IRIN News @irinnews, 13 September 2017

With 370,000 Rohingya in Bangladesh, close to half the Rohingya population of Northern Rakhine State has left. Govt figure for 2016: 755,371: image via LaetitiavandenAssum @lvandenassum, 12 September 2017

00048af6 Smoke is seen on Myanmar's side of border as an exhausted Rohingya refugee woman is carried to the shore after crossing the Bangladesh-Myanmar border by boat through the Bay of Bengal, in Shah Porir Dwip, Bangladesh September 11, 2017. (Photo by Danish Siddiqui/Reuters): image by Jean Bosco SIBOMANA, 12 September 2017

000488e7 A Rohingya refugee girl sits next to her mother who rests after crossing the Bangladesh-Myanmar border, in Teknaf, Bangladesh, September 6, 2017. (Photo by Danish Siddiqui/Reuters): image by Jean Bosco SIBOMANA, 10 September 2017

000488e7 A Rohingya refugee girl sits next to her mother who rests after crossing the Bangladesh-Myanmar border, in Teknaf, Bangladesh, September 6, 2017. (Photo by Danish Siddiqui/Reuters): image by Jean Bosco SIBOMANA, 10 September 2017

000488e7 A Rohingya refugee girl sits next to her mother who rests after crossing the Bangladesh-Myanmar border, in Teknaf, Bangladesh, September 6, 2017. (Photo by Danish Siddiqui/Reuters): image by Jean Bosco SIBOMANA, 10 September 2017

000489a1Rohingya refugees walk on a muddy path after crossing the Bangladesh-Myanmar border in Cox's Bazar, Bangladesh September 8, 2017. (Photo by Danish Siddiqui/Reuters): image by Jean Bosco SIBOMANA, 11 September 2017

000489a1Rohingya refugees walk on a muddy path after crossing the Bangladesh-Myanmar border in Cox's Bazar, Bangladesh September 8, 2017. (Photo by Danish Siddiqui/Reuters): image by Jean Bosco SIBOMANA, 11 September 2017

000489a1Rohingya refugees walk on a muddy path after crossing the Bangladesh-Myanmar border in Cox's Bazar, Bangladesh September 8, 2017. (Photo by Danish Siddiqui/Reuters): image by Jean Bosco SIBOMANA, 11 September 2017

000488e6 A Rohingya refugee carries a child through a paddy field after crossing the Bangladesh-Myanmar border, in Teknaf, Bangladesh, September 6, 2017. (Photo by Danish Siddiqui/Reuters): image by Jean Bosco SIBOMANA, 11 September 2017

000488e6 A Rohingya refugee carries a child through a paddy field after crossing the Bangladesh-Myanmar border, in Teknaf, Bangladesh, September 6, 2017. (Photo by Danish Siddiqui/Reuters): image by Jean Bosco SIBOMANA, 11 September 2017

000488e6 A Rohingya refugee carries a child through a paddy field after crossing the Bangladesh-Myanmar border, in Teknaf, Bangladesh, September 6, 2017. (Photo by Danish Siddiqui/Reuters): image by Jean Bosco SIBOMANA, 11 September 2017

000488e8 Rohingya refugees walk to the shore with their belongings after crossing the Bangladesh-Myanmar border by boat through the Bay of Bengal in Teknaf, Bangladesh, September 5, 2017. (Photo by Mohammad Ponir Hossain/Reuters): image by Jean Bosco SIBOMANA, 10 September 2017

000488e8 Rohingya refugees walk to the shore with their belongings after crossing the Bangladesh-Myanmar border by boat through the Bay of Bengal in Teknaf, Bangladesh, September 5, 2017. (Photo by Mohammad Ponir Hossain/Reuters): image by Jean Bosco SIBOMANA, 10 September 2017

000488e8 Rohingya refugees walk to the shore with their belongings after crossing the Bangladesh-Myanmar border by boat through the Bay of Bengal in Teknaf, Bangladesh, September 5, 2017. (Photo by Mohammad Ponir Hossain/Reuters): image by Jean Bosco SIBOMANA, 10 September 2017

0004899f A man carries a Rohingya refugee woman from the shore after she

crossed the Bangladesh-Myanmar border by boat through the Bay of Bengal

in Teknaf, Bangladesh September 7, 2017. (Photo by Danish

Siddiqui/Reuters): image by Jean Bosco SIBOMANA, 11 September 2017

0004899f A man carries a Rohingya refugee woman from the shore after she

crossed the Bangladesh-Myanmar border by boat through the Bay of Bengal

in Teknaf, Bangladesh September 7, 2017. (Photo by Danish

Siddiqui/Reuters): image by Jean Bosco SIBOMANA, 11 September 2017

0004899f A man carries a Rohingya refugee woman from the shore after she

crossed the Bangladesh-Myanmar border by boat through the Bay of Bengal

in Teknaf, Bangladesh September 7, 2017. (Photo by Danish

Siddiqui/Reuters): image by Jean Bosco SIBOMANA, 11 September 2017

0004881a Rohingya refugees sit as they are temporarily held by the Border Guard Bangladesh (BGB) in an open area after crossing the border, in Teknaf, Bangladesh, September 3, 2017. (Photo by Mohammad Ponir Hossain/Reuters): image by Jean Bosco SIBOMANA, 11 September 2017

0004881a Rohingya refugees sit as they are temporarily held by the Border Guard Bangladesh (BGB) in an open area after crossing the border, in Teknaf, Bangladesh, September 3, 2017. (Photo by Mohammad Ponir Hossain/Reuters): image by Jean Bosco SIBOMANA, 11 September 2017

0004881a Rohingya refugees sit as they are temporarily held by the Border Guard Bangladesh (BGB) in an open area after crossing the border, in Teknaf, Bangladesh, September 3, 2017. (Photo by Mohammad Ponir Hossain/Reuters): image by Jean Bosco SIBOMANA, 11 September 2017

00048818 Rohingya refugees walk on the muddy path after crossing the Bangladesh-Myanmar border in Teknaf, Bangladesh, September 3, 2017. (Photo by Mohammad Ponir Hossain/Reuters): image by Jean Bosco SIBOMANA, 11 September 2017

00048818 Rohingya refugees walk on the muddy path after crossing the Bangladesh-Myanmar border in Teknaf, Bangladesh, September 3, 2017. (Photo by Mohammad Ponir Hossain/Reuters): image by Jean Bosco SIBOMANA, 11 September 2017

00048818 Rohingya refugees walk on the muddy path after crossing the Bangladesh-Myanmar border in Teknaf, Bangladesh, September 3, 2017. (Photo by Mohammad Ponir Hossain/Reuters): image by Jean Bosco SIBOMANA, 11 September 2017

Framing the Rohingya: Fake News

As Maungdaw burns, official narrative goes up in smoke: Nyan Hlaing Lynn, Frontier (Myanmar), 12 September 2017

Around the lush green paddy fields, herds of cattle and goats roam

freely without their owners, set against a backdrop of the rolling Mayu

Mountains. Off in the distance, occasional plumes of smoke can be seen

sprouting up into the sky.

This is Maungdaw, the sparse district in northern Rakhine State that

has been the scene of heightened security, and violence, for the better

part of a year following the emergence of a militant group known as the

Arakan Rohingya Salvation Army.

ARSA first made their presence known on October 9 last year, with

attacks on Border Guard Police outposts that saw almost a dozen security

officers killed. The attacks led to a months-long security operation

that came with accusations of disproportionate force, a charge

continuously denied by the military and civilian government.

Police officer on patrol in Alae Than Kyaw village in Maungdaw Township last week.: photo by Nyan Hlaing Lynn via Frontier, 9 September 2017

After a period of relative calm, ARSA again launched attacks on the

morning of August 25, just hours after the Advisory Commission on

Rakhine State, headed by former UN secretary-general Kofi Annan,

submitted its final report to the Myanmar government.

Violence, fear and distrust have returned to northern Rakhine and the conflict at this point appears intractable.

I have had the opportunity to visit the region on two separate

occasions. The first visit was immediately after the October 9 attacks

and the second shortly after the latest uptick of violence started.

Independent media face restrictions accessing the region and both of

these visits were on media trips organised and tightly controlled by the

government.

Our recent trip took place on September 6 and 7, with 18 journalists

from domestic and international media visiting some of the communities

affected by the latest violence. Due to time constraints, we were not

able to get a full grasp of the situation on the ground, but the trip

did offer some insights.

Staged photos

One of our first visits was to a small school on the outskirts of

Maungdaw town that was being used as a camp for Hindus displaced by the

violence.

“There’s no one around here. I’m scared,” said our first interviewee, a Hindu motorbike repairman.

The people there all told us that attacks had been launched by

Muslims, forcing them to flee. They said they were taking shelter at the

school, which was guarded by security forces, and were too scared to

return to their homes. According to a government statement, three homes

in their ward had been burned by ARSA extremists on August 26.

A

photo provided to reporters that appeared to show Muslims burning their

own homes. Evidence later emerged that the photos were staged.

(Supplied): image via Frontier, 9 September 2017

From there we were taken to the Zawtikayon monastery, where a monk told us he had seen Muslims burning down homes nearby.

“When they set the houses on fire, I went and told them to stop,” the monk told us.

We were then shown photos apparently of the incident the monk had

witnessed. They looked questionable. They showed men in Muslim-style

caps burning down a thatched roof, as women – with what appeared to be

tablecloths over their heads – stood nearby waving machetes.

Evidence later emerged that one woman in the photos was among the

group of “displaced Hindus” we had earlier interviewed, while another

man in the photos wearing a distinctive checked shirt and longyi had

also been seen at the displacement camp.

Clearly, the photos had been staged.

A

monk told reporters he had seen Muslims setting fire to homes, but

evidence later emerged that the photos had been staged.: photo by Nyan Hlaing

Lynn | Frontier, 9 September 2017

Widespread distrust

We then visited a Muslim village called Shwe Zar. Before the

violence, the village had been home to about 15,000 residents, but

during our visit we saw just a handful of people walking along the

street, and most of the doors to the homes were closed.

“There are people inside – no one fled from this village,” said local

resident Roshi Amad, 59, who was concerned that his two sons, both who

are in 10th standard, would not be allowed to return to school to

complete their education.

“If people are allowed to do their business, their livelihoods, I think everything will be calm and peaceful,” Roshi Amad said.

Hindu

residents fleeing the violence sparked by the August 25 attacks took

refuge at a makeshift IDP camp in Maungdaw town.: photo Nyan Hlaing Lynn |

AFP via Frontier, 9 September 2017

When we asked him about the violence, he repeatedly told us he could

not say anything. Many other villagers we tried to interview refused to

speak with us, while others expressed concern that ARSA had taken root

in their village.

“We don’t have terrorists. We don’t want violence,” said Mamad Zawli,

48, who later told us that the key to improving the situation would be

for authorities to work closely with residents from all communities.

Mamad Zawli was the only Muslim we met during the trip who holds a

National Registration Card, but even he cannot leave the village

currently. One thing all the residents we met in the village agreed on

was the fact that Muslims and Rakhine had lived and worked peacefully

side by side before, but that the distrust was so strong that a return

to normalcy was not possible for the time being.

He believes that the key to re-building trust in the region is for authorities and the local people to work side by side.

On the following day when we reached Myoma Kanyindan village, a

Muslim betel seller told reporters that the government was not doing

enough to resolve the situation.

“International assistance is needed. The government is not doing enough and now we can’t go anywhere,” said the vendor.

Charred villages

Charred villages

At Mawrawady village, we spoke to ethnic Rakhine who said they had

been frequently threatened by Muslims living in surrounding villages.

Originally home to about 600 residents, only about 120 remain, with the

rest having fled for Maungdaw town or Sittwe.

“If [the violence] continues to happen, we can no longer live here,”

said resident U San Hla Phyu, 57. “Formerly both communities were

interdependent and worked and lived together. I can’t understand why

violence suddenly erupted here.”

He called on the government to grant citizenship to those who can

prove they qualify under the 1982 citizenship law and said those who

cannot should be put into camps.

“We can live together with them,” he said.

At another village, Alethankyaw, Muslim and Rakhine residents had

lived side by side, even after the October attacks. But that changed

after the latest violence, when a Border Guard Police outpost was

attacked, thousands of people fled and an immigration officer killed.

Now, Alethankyaw is silent, except for ashes and smoke, and only a few

residents remain.

The charred remains of homes in Alae Than Kyaw village: photo by Nyan Hlaing Lynn via Frontier, 9 September 2017

“I heard people shouting ‘Kill, kill’ nearby, and when I came out and

looked I saw that they [ARSA] had captured more than half of the

[police] camp,” said Daw Thet Thet recalling the events.

The attack appeared to pit neighbours against neighbours in some cases. Thet Thet told Frontier that she recognised some of those who had launched the attacks.

“I didn’t think the situation would be so bad,” she said.

Police-Lieutenant Aung Kyaw Moe, who oversees security in the

village, said he had received a tip-off that an attack was being planned

so moved the ethnic Rakhine and government staff to a nearby camp in

advance.

Authorities then escorted the reporters along a nearby track. After

half an hour we reached an area where damage from a recent fire had

caused widespread devastation and sporadic sounds of gunfire could be

heard in the distance.

We continued further along the track and eventually reached the top

of a hill from where we could see the beautiful Bay of Bengal in the

distance.

We then noticed a figure moving slowly towards us. As he got closer,

we saw that it was a man carrying some belongings. Immediately upon

seeing us, he sat down quickly and held up his hands.

His name was Haribraman, 55. He said he had been walking for two days

from a village called Thawun Chaung that had witnessed fighting between

security forces and ARSA. His family was following closely behind, he

said, and he was hoping to take a boat to Bangladesh.

We left Haribraman to his journey and made our way back to the

vehicles for the return journey to Maungdaw town. While travelling along

the road, we passed a village that was on fire. After some negotiation

with the authorities, we were allowed to stop.

The village was called Gawduthara and had been Muslim-majority before

the residents had fled. We could see religious books, some with Arabic

script, strewn across the floor. An empty plastic jug, smelling of

petrol, was sitting on the floor.

A home in Gawduthara village ablaze on the afternoon of September 7: photo by Nyan Hlaing Lynn | Frontier, 7 September 2017

We could see no Muslims in the area, but we could see some people –

who appeared to be Rakhine by their appearance – standing around

watching in small groups. Some were holding swords or machetes. Frontier approached

one of the unarmed men and asked what he had seen. He said he was from a

nearby village and that “Bengalis” – a term many in Myanmar use to call

the Muslim minority who identify as Rohingya – had set fire to their

houses at 5am that morning.

I checked my watch. It was 1:44pm, almost nine hours after the man

said the fires had been lit. It was clear that the fires flickering

before us had been set much more recently than that.

Authorities have claimed that Muslims are setting fire to their own homes and blaming it on the military.

Colonel Phone Thit, state minister for security and border affairs,

had previously told us that the “Bengali terrorists” had set fire to the

villages to make local residents scared of them. “Their plans are

successful if the villagers are displaced and the international

community condemns the military,” he said.

“That’s why they set fire to

the homes.”

But as I stood watching the flames, I recalled a conversation from a

day earlier with the Muslim betel seller in Myoma Kanyindan village.

“It’s not like that,” he said, referring to reports that Muslims had

set fire to their own homes. “We know who did it. It’s impossible for

someone to set fire to their own home. Impossible.”

Framing the Rohingya: Their eyes are blank. They've seen everything. "Everything has turned to ashes."

Framing the Rohingya: Their eyes are blank. They've seen everything. "Everything has turned to ashes."

In this Sept. 5, 2017 photo, newly arrived Rohingya rest in a makeshift tent in Kutupalong, Bangladesh.: photo by Bernat Armangue/AP, 5 September 2017

Rohingya scuffle to get clothes from local volunteers Kutupalong, Bangladesh, Friday, Sept. 8, 2017.: photo by Bernat Armangue/AP, 8 September 2017

A Rohingya man holds the body of a two-day-old baby before his burial at Kutupalong's refugee camp cemetery, Sept. 8, 2017, Bangladesh. On Friday, two infants were interred there. A six-day-old baby, who was born on the road as his family escaped, was buried next to the two-day-old child born to a woman from the old camp.: photo by Bernat Armangue/AP, 8 September 2017

A Rohingya man holds the body of a two-day-old baby before his burial at Kutupalong's refugee camp cemetery, Sept. 8, 2017, Bangladesh. On Friday, two infants were interred there. A six-day-old baby, who was born on the road as his family escaped, was buried next to the two-day-old child born to a woman from the old camp.: photo by Bernat Armangue/AP, 8 September 2017

00048866 A Rohingya family reaches the Bangladesh border after crossing a creek of the Naf river on the border with Myanmar, in Cox's Bazar's Teknaf area, Tuesday, Sept. 5, 2017. (AP Photo/Bernat Armangue): image by Jean Bosco SIBOMANA, 11 September 2017

A Rohingya family reaches the Bangladesh border after crossing a creek of the Naf river on the border with Myanmar, in Cox's Bazar's Teknaf area, Tuesday, Sept. 5, 2017. (AP Photo/Bernat Armangue): image by Jean Bosco SIBOMANA, 11 September 2017

A Rohingya family reaches the Bangladesh border after crossing a creek of the Naf river on the border with Myanmar, in Cox's Bazar's Teknaf area, Tuesday, Sept. 5, 2017. (AP Photo/Bernat Armangue): image by Jean Bosco SIBOMANA, 11 September 2017

Bengali (Border of the Frame)

![Daily Soap_Dhaka#2 | by ShifaturShantu [The Craftsman]](https://c1.staticflickr.com/5/4339/36985835401_c0f1ca7738_h.jpg)

No comments:

Post a Comment