West Mesa, Albuquerque, New Mexico: photo by Jorge Guadalupe Lizárraga, September 2017

West Mesa, Albuquerque, New Mexico: photo by Jorge Guadalupe Lizárraga, September 2017

West Mesa, Albuquerque, New Mexico: photo by Jorge Guadalupe Lizárraga, September 2017

I Intersectionality: Was the sky too large for them?

Your dream is my nightmare, I said to the unkempt giant barking spider doll who refused to shut upEveryone was starting to run. Get down! someone yelled. Did you hear that? Firecrackers? Get down!

Just don't take away my god given gun

Don't worry about it. The screaming, the glass and shell fragments.

It's probably nothing at all. You know, just another behavioral experiment.

What's that wet stuff? Did you hear something?

It's getting really dark, I think. Like, almost even darker than before.

There was then an adjustment of the horizon. The mountains seemed

nearer, the desert moved off farther and farther away.

And yet the traffic, so dense now no one was even noticing... and the ocean...

Do not look at the pavement in that Parking lot. Repeat not.

San Francisco Pastoral. San Francisco, Ca.: photo by Robert Ogilvie, 1 October 2017

Truth or Consequences, New Mexico: photo by Jorge Guadalupe Lizárraga, July 2017

Truth or Consequences, New Mexico: photo by Jorge Guadalupe Lizárraga, July 2017

Truth or Consequences, New Mexico: photo by Jorge Guadalupe Lizárraga, July 2017

Large Collection [Hamilton, Ontario]: photo by Tyler Wilson, 17 March 2015

San Mateo, CA: photo by Ivan Echevarria, 30 September 2017

San Mateo, CA: photo by Ivan Echevarria, 30 September 2017

San Mateo, CA: photo by Ivan Echevarria, 30 September 2017

West Indian School Road. Phoenix, Arizona.: photo by Dean Terasaki, 27 August 2017

West Indian School Road. Phoenix, Arizona.: photo by Dean Terasaki, 27 August 2017

West Indian School Road. Phoenix, Arizona.: photo by Dean Terasaki, 27 August 2017

Untitled: photo by Missy Prince, 1 October 2017

Untitled: photo by Missy Prince, 1 October 2017

Untitled: photo by Missy Prince, 1 October 2017

Athletes stage on-field protests as President Trump calls for team owners to fire those who refuse to stand: image via AP Images @AP_Images, 1 October 2017

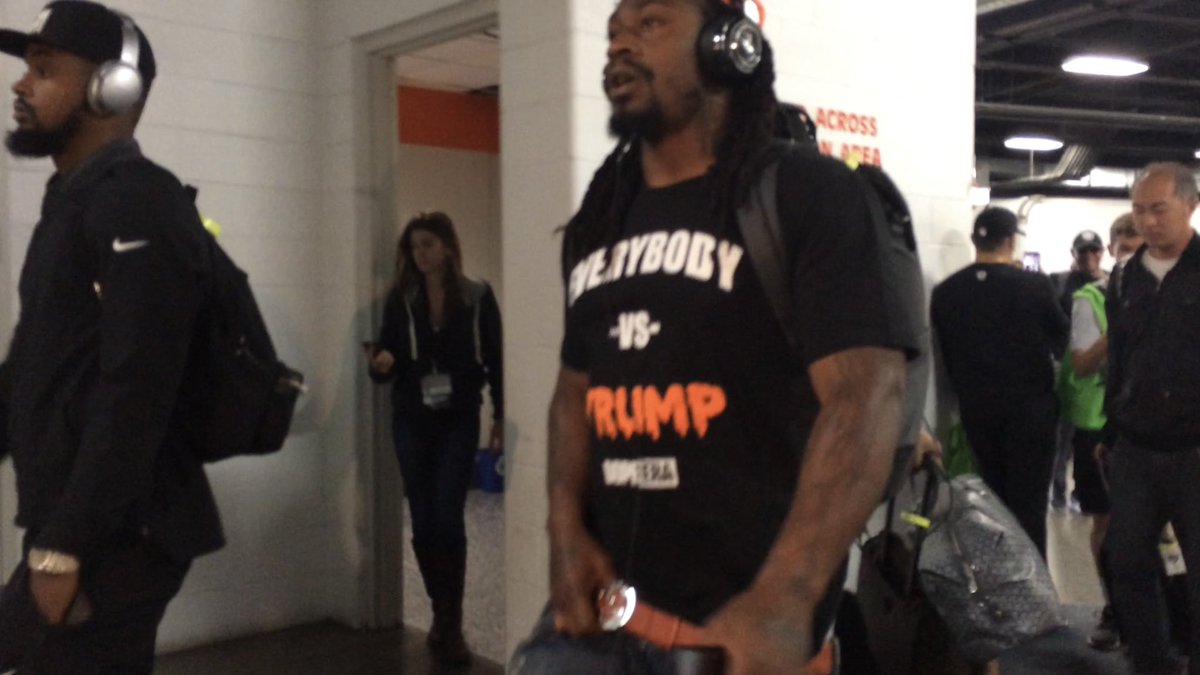

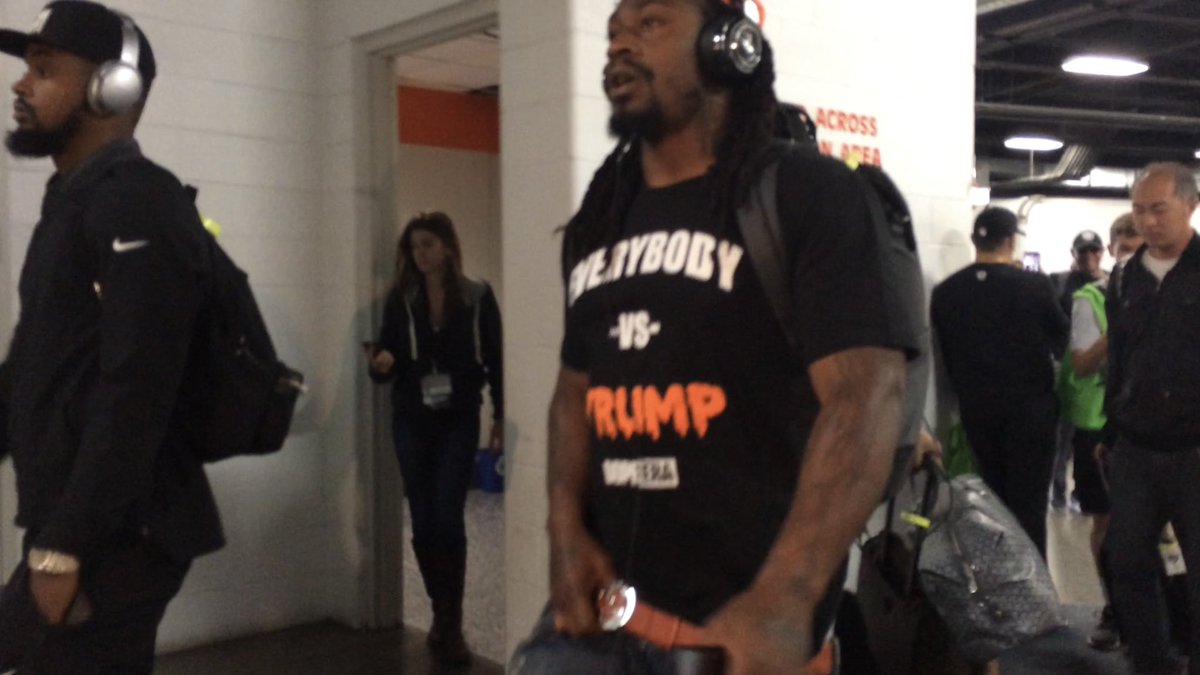

Marshawn Lynch arriving in a "Everybody vs. Trump" shirt #RaiderNation: image via Fanatics View @thefanaticsview, 1 October 2017

At least one gunman reported to have opened fire at Las Vegas music festival, hundreds fleeing from the scene: image via BBC Breaking News @BBCBreaking, 1 October 2017

At least one gunman reported to have opened fire at Las Vegas music festival, hundreds fleeing from the scene: image via BBC Breaking News @BBCBreaking, 1 October 2017

At least one gunman reported to have opened fire at Las Vegas music festival, hundreds fleeing from the scene: image via BBC Breaking News @BBCBreaking, 1 October 2017

At least one gunman reported to have opened fire at Las Vegas music festival, hundreds fleeing from the scene: image via BBC Breaking News @BBCBreaking, 1 October 2017

Multiple victims hospitalised with 'gunshot wounds' after shooting at Las Vegas country music festival: image via BBC Breaking News @BBCBreaking, 1 October 2017

STURDY SAFE. Fresno, Ca.: photo by akahawkeyefan, 30 September 2017

STURDY SAFE. Fresno, Ca.: photo by akahawkeyefan, 30 September 2017

STURDY SAFE. Fresno, Ca.: photo by akahawkeyefan, 30 September 2017

Elmyra St. [DTLA]: photo by Andrew Murr, 1 October 2017

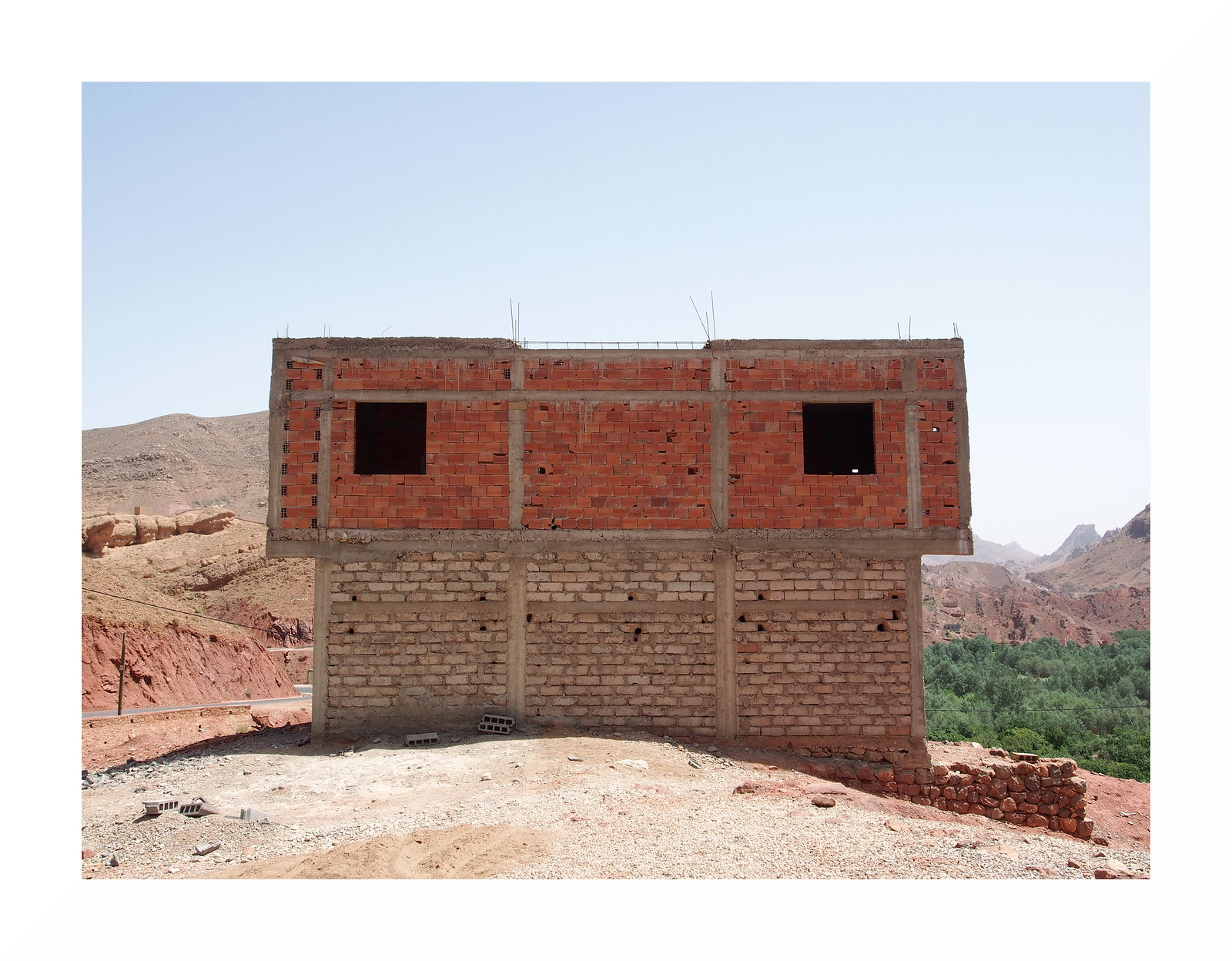

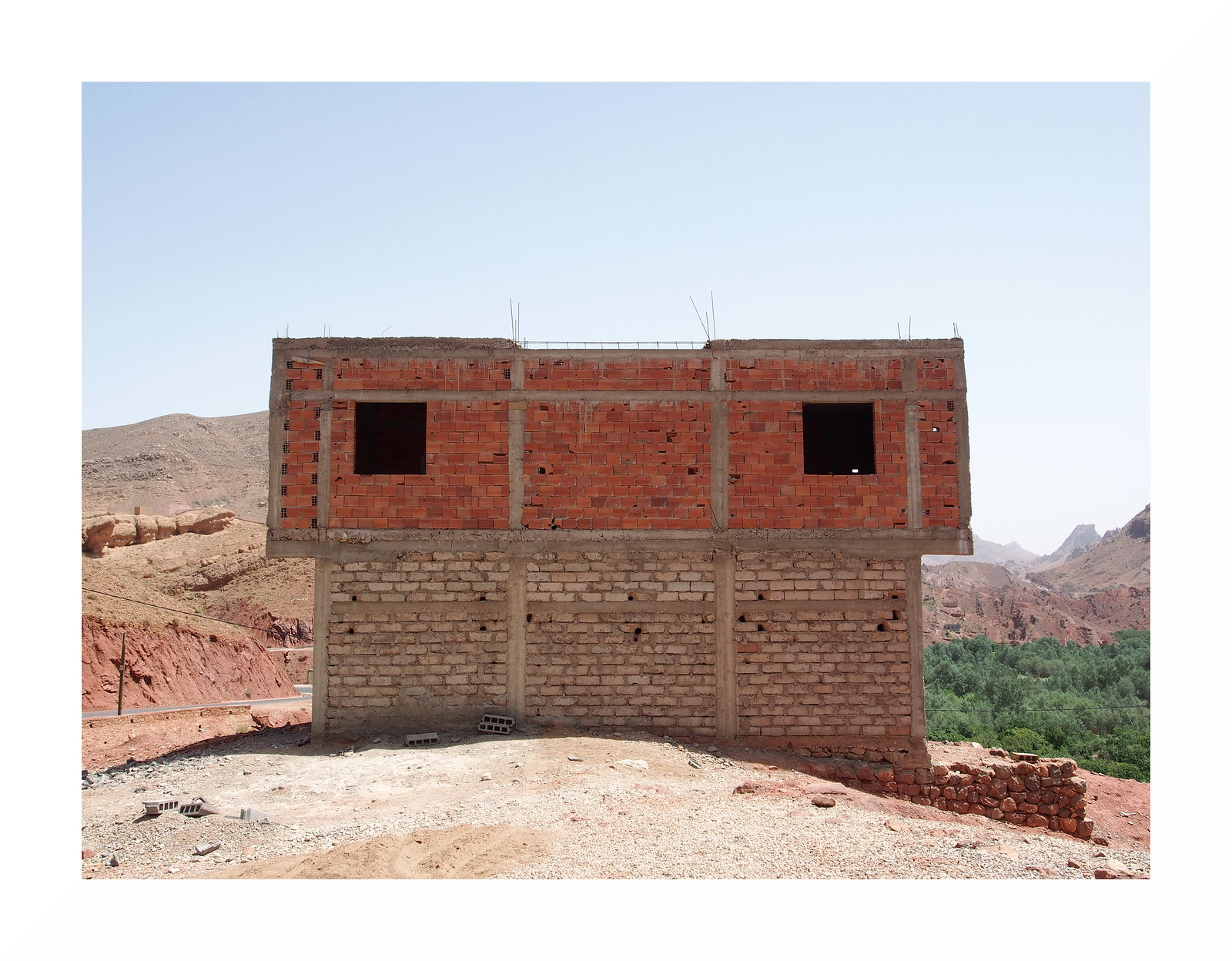

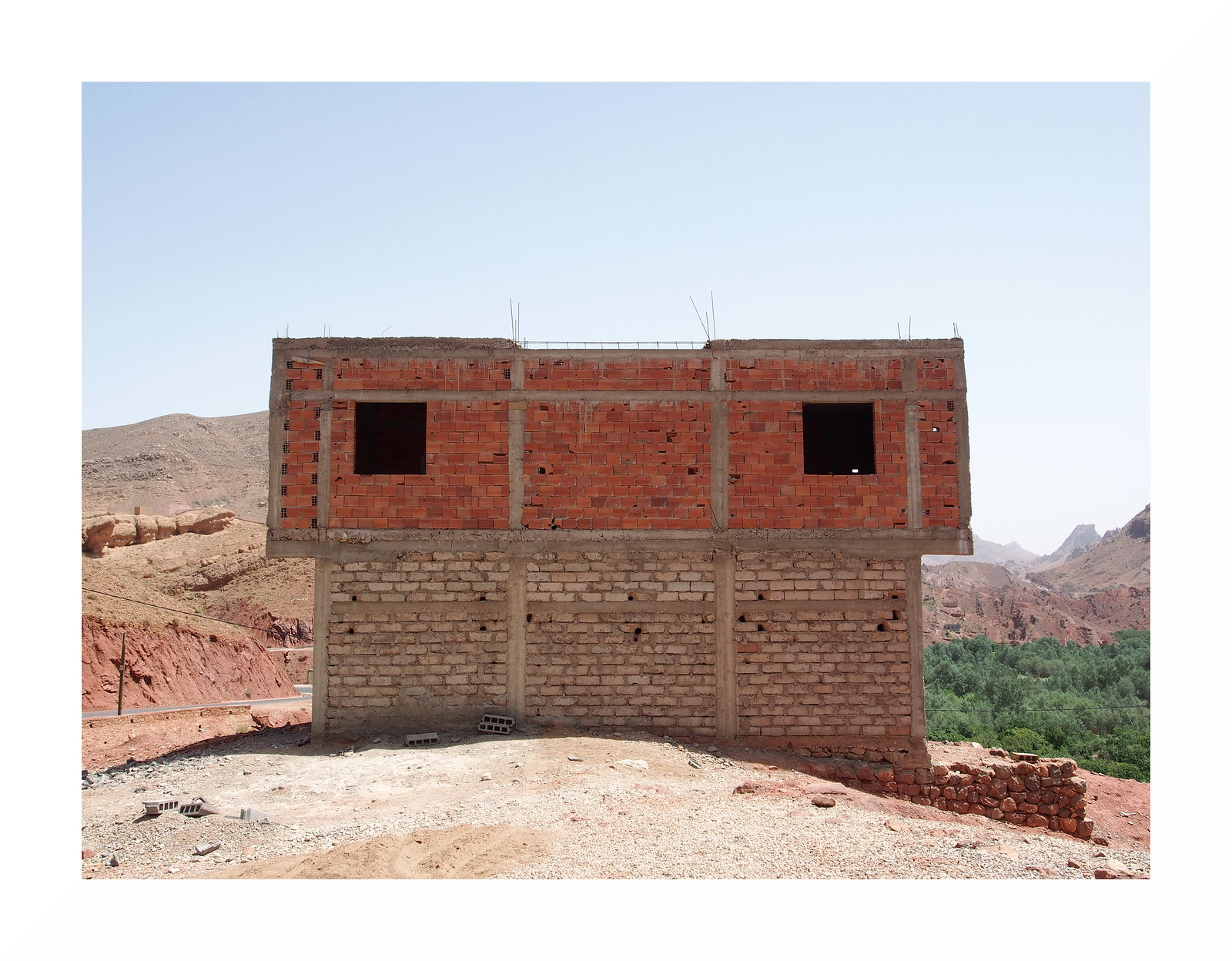

Morocco: photo by Mathieu Forcier, 27 September 2017

Morocco: photo by Mathieu Forcier, 27 September 2017

Untitled [Naples]: photo by Andrew Murr, 30 September 2017

Blue car mattress tarp [DTLA]: photo by Andrew Murr, 30 September 2017

Untitled [LA]: photo by Andrew Murr, 30 September 2017

salton sea: photo by live..simply, 27 September 2017

salton sea: photo by live..simply, 27 September 2017

salton sea: photo by live..simply, 27 September 2017

Ocean Beach, San Francisco: photo by Bill, 30 September 2017

the hunter [Tempe, Arizona]: photo by m.r. nelson, 24 September 2017

the hunter [Tempe, Arizona]: photo by m.r. nelson, 24 September 2017

the hunter [Tempe, Arizona]: photo by m.r. nelson, 24 September 2017

Untitled [Navajo, Arizona]: photo by Patrick, April 2017

2017-191. Berkeley, CA.: photo by biosfear, August 2017

2017-192. Oakland, CA.: photo by biosfear, 24 September 2017

Downtown Minneapolis #7. Minneapolis, Minnesota.: photo by Dean Terasaki, 10 March 2017

Downtown Minneapolis #7. Minneapolis, Minnesota.: photo by Dean Terasaki, 10 March 2017

Downtown Minneapolis #7. Minneapolis, Minnesota.: photo by Dean Terasaki, 10 March 2017

2017-195. Oakland, CA.: photo by biosfear, September 2017

Untitled [Monument Valley, Utah]: photo by Patrick, April 2017

salton sea: photo by live..simply, 27 September 2017

Death Valley: photo by Missy Prince, 29 September 2017

Death Valley: photo by Missy Prince, 29 September 2017

Death Valley: photo by Missy Prince, 29 September 2017

the far reaches, mojave desert, ca. 2015. tucked away in the far northwest corner of the antelope valley lies a collection of tumbledown cabins, most abandoned.: photo by eyetwist, 30 May 2015

Linnton, Portland, Oregon: photo by Jorge Guadalupe Lizárraga, February 2013

Linnton, Portland, Oregon: photo by Jorge Guadalupe Lizárraga, February 2013

side view [Alpena, Michigan]: photo by Ben Thompson, 22 July 2017

side view [Alpena, Michigan]: photo by Ben Thompson, 22 July 2017

side view [Alpena, Michigan]: photo by Ben Thompson, 22 July 2017

Dry Pasture [Coastal CA]: photo by Andrew Murr, 29 September 2017

Who gets the middle? [Deutschtown, Pittsburgh]: photo by David Grim, 20 April 2017

Who gets the middle? [Deutschtown, Pittsburgh]: photo by David Grim, 20 April 2017

Who gets the middle? [Deutschtown, Pittsburgh]: photo by David Grim, 20 April 2017

No Loitering [Helena, Ark.]: photo by Andrew Murr, 29 September 2017

The loneliness of the short distance driver [Toledo, Ohio]: photo by Robert Saucier, 29 September 2017

The loneliness of the short distance driver [Toledo, Ohio]: photo by Robert Saucier, 29 September 2017

The loneliness of the short distance driver [Toledo, Ohio]: photo by Robert Saucier, 29 September 2017

The loneliness of the short distance driver [Toledo, Ohio]: photo by Robert Saucier, 29 September 2017

The loneliness of the short distance driver [Toledo, Ohio]: photo by Robert Saucier, 29 September 2017

The loneliness of the short distance driver [Toledo, Ohio]: photo by Robert Saucier, 29 September 2017

John and Andrew Fox's house, after eviction, Clongorey, County Kildare: photo by Robert French, c. 1888 (Lawrence Photographic Collection National Library of Ireland)

John and Andrew Fox's house, after eviction, Clongorey, County Kildare: photo by Robert French, c. 1888 (Lawrence Photographic Collection National Library of Ireland)

John and Andrew Fox's house, after eviction, Clongorey, County Kildare: photo by Robert French, c. 1888 (Lawrence Photographic Collection National Library of Ireland)

II earth is in the hands of the wrong people -- horrors on another level, if that's even possible

Rohingya refugee Minara Begum, 18, holds her sick nine-day old-daughter, in Cox's Bazar, Bangladesh. REUTERS/Cathal McNaughton: image via Cathal McNaughton @Cathal1978, 1 October 2017

Rohingya refugee and mother of eight Shalida Begum, 25, waits to be transferred to a camp in Cox's Bazar. REUTERS/Cathal McNaughton: image via Cathal McNaughton @Cathal1978, 2 October 2017

Newly arrived Rohingya refugees board a boat as they transfer to a camp in Cox's Bazar, Bangladesh. REUTERS/Cathal McNaughton: image via Cathal McNaughton @Cathal1978, 2 October 2017

Rohingya

collapse exhausted from trip and from fear. Then they get up, pick up

their children and start walking into miserable unknown: image via Damir Sagolj @damirsagolj, 2 October 2017

Of almost 500K Rohingya refugees who recently fled Myanmar more than half are children. Fled with fear and trauma. And now what?: image via Damir Sagolj @damirsagolj, 2 October 2017

Of almost 500K Rohingya refugees who recently fled Myanmar more than half are children. Fled with fear and trauma. And now what?: image via Damir Sagolj @damirsagolj, 2 October 2017

Just off the Inani beach where their boat capsized yesterday a Rohingya man buried his three daughters, another one three children and wife.: image via Damir Sagolj, 29 September 2017

To hear about horrors on another level, if that's even possible, there is a special Rohingya ward at hospital in Cox's Bazar:

image via Damir Sagolj, 30 September 2017

Rohingya Muslim refugee walks on the shore after crossing the Naf River to Bangladesh from Myanmar. #afp @freddufour: image via Fred Dufour @freddufour_afp, 29 September 2017

Rohingya refugees react before the funeral of a family member who they say died from injuries sustained in Myanmar. REUTERS/Cathal McNaughton: image via Cathal McMaughton @Cathal1078, 29 September 2017

A Rohingya boy stands next to his father, whose family say succumbed to injuries inflicted by the Myanmar Army. REUTERS/Cathal McNaughton: image via Cathal McNaughton @Cathal1078, 29 September 2017

A Rohingya boy stands next to his father, whose family say succumbed to injuries inflicted by the Myanmar Army. REUTERS/Cathal McNaughton: image via Cathal McNaughton @Cathal1078, 29 September 2017

A Rohingya Muslim Mohamed Rafiq hands a drink of water and

biscuits to his wife Noora Khatum who lies exhausted on the ground as

they reach Teknaf, Bangladesh, Friday, Sept. 29, 2017. He trekked to

Bangladesh as part of an exodus of a half million people from Myanmar,

the largest refugee crisis to hit Asia in decades. But after climbing

out of a boat on a creek on Friday, Rafiq could go no further. He

collapsed onto a muddy spit of land cradling his wife in his lap, a limp

figure so exhausted and so hungry she could no longer walk or even

raise her wrists.: photo by Gemunu Amarasinghe/AP, 29 September 2017

Myanmar refugee exodus tops 500,000 as more Rohingya flee: Todd Pitman, AP, 30 September 2017

TEKNAF, Bangladesh (AP) — He trekked to Bangladesh as part of an

exodus of a half million people from Myanmar, the largest refugee crisis

to hit Asia in decades. But after climbing out of a boat on a creek on

Friday, Mohamed Rafiq could go no further.

He collapsed onto a muddy spit of land cradling his wife in his lap — a limp figure so exhausted and so hungry she could no longer walk or even raise her wrists.

The couple had no food, no money, no idea what to do next. Their two traumatized children huddled close beside them, unsure what to make of the country they had arrived in just hours earlier, in the middle of the night.

Rafiq said their third child, an 8-month-old boy, had been left behind. Buddhist mobs in Myanmar burned the child to death, he said, after setting their village ablaze while security forces stood idly by — part of a systematic purge of ethnic Rohingya Muslims from Buddhist-majority Myanmar that the United Nations has condemned as “a textbook example of ethnic cleansing.”

Five weeks after the mass exodus began on Aug. 25, the U.N. says the total number of arrivals in Bangladesh has now topped 501,000.

And still, they keep coming.

“We don’t ever want to go back,” a stunned Rafiq said, describing his family’s ordeal as Bangladeshi volunteers stuffed a small wad of cash into his hand and gave their children biscuits. Another man offered a bottle of water, and Rafiq poured some into his wife’s mouth as she lay in his arms, staring blankly at the sky.

“This is not our home. It is not our country,” Rafiq said. “But at least, we feel safe here.”

Not all those who have fled over the last few desperate weeks have survived. The International Organization for Migration said more than 60 refugees were confirmed dead or missing and presumed dead after one vessel capsized on rough seas in the area Thursday.

The crisis began when a Rohingya insurgent group launched attacks with rifles and machetes on a series of security posts in Myanmar on Aug. 25, prompting the military to launch a brutal round of “clearance operations” in response.

Those fleeing have described indiscriminate attacks by security forces and Buddhist mobs, including monks, as well as killings and rapes.

While the international community has condemned the violence and called on Myanmar to protect the Rohingya, Sufi Ullah, a police officer in Teknaf, said nothing has changed.

“We’re seeing them come across whenever they get the chance,” Ullah said.

“They’re hiding themselves in the forests and hills (inside Myanmar) in the daytime. And when they get the chance, they run. The Myanmar army is putting pressure on them. These people are afraid.”

Ullah said several thousand new refugees arrived by boat in Bangladesh on Friday, and authorities were not expecting the flow to let up any time soon.

On Friday, dramatic scenes played out over and over as hordes of Rohingya who had crossed into Bangladesh overnight tried to make their way further inland. They trudged out of boats and through mud that in some places was knee deep. Men carried babies and old women on their backs. Everyone was exhausted.

Sonabanu Chemmon was among those too weak to walk. Her son-in-law had carried her to one of Bangladeshi’s inland creeks, near Shah Porir Dip. But he then abandoned her along with several of her adult daughters.

Asked why, Chemmon covered her eyes as tears fell down her cheeks.

“He said he had carried me far enough, that he couldn’t carry me anymore,” she said. “He told me, ‘You can make it from here. I have to look after my own children.’”

Chemmon was finally helped by several Bangladeshis who are among a small army of local citizenry collecting donations, food and clothing, and handing it out to desperate new arrivals.

“Some of these people haven’t eaten or slept in days. They’re so weak, they can’t even walk,” said Mohamed Ismail, a Bangladeshi volunteer who traveled here from the city of Chittagong.

“I’ve never seen anything like it. They have nothing. It’s painful to watch,” he said, turning away, overcome with emotion. “Bangladesh is not rich, but we have to help.”

Karim Elguindi, who heads the U.N. World Food Program office in Cox’s Bazar, described the scene Friday as “distressing.”

“There’s more and more people coming and there’s not enough space in the existing camps” to accommodate them, said Elguindi, who was touring the area after hearing a new influx was underway. “I don’t know how many Rohingya are left in Myanmar ... but there’s more on the way.”

Elguindi said many of the refugees had been traveling for five days or more, and many were not carrying food during the journey. “These people are very vulnerable, very hungry ... they need shelter, they need water.”

Myanmar’s government, led by Nobel Peace Prize winner Aung San Suu Kyi, and its still powerful military do not allow independent media free access to northern Rakhine state, from where the Rohingya are fleeing. While fires are no longer visible from the Bangladeshi border, some refugees told The Associated Press that their homes had been burned as recently as two days ago.

Rafiq said he and his wife, Noor Khatum, fled their home in the Maungdaw village in Khai Dar Para in the first week of September, after police and soldiers moved in and Buddhist mobs, including monks, set fire to homes there in the middle of the night.

Rafiq managed to get his 5-year-old daughter out, while his wife carried their 2-year-old son. But their house, made of wood and sticks, burned quickly, collapsing on their baby boy before they could save him.

After fleeing, they took shelter with relatives in another village, but several days later that village, too, was torched by Buddhist mobs. Rafiq and his family then hid with others in an abandoned house near the border for two weeks, but had no money to pay boatmen to take them across the Naf River to Bangladesh.

So for two days, Rafiq helped other families escape, carrying them and their goods in exchange for amounts of cash. On Friday at 3 a.m., his own family finally made it out.

Now, in Bangladesh, a far more uncertain chapter of their lives has begun.

“We don’t know where we will go,” Rafiq said forlornly, as a long line of families trudged single file toward the town of Teknaf, where authorities were assessing the new arrivals and trucking them to camps further north. “We have nothing. We don’t know what we will do.”

A newly arrived Rohingya Muslim Mohamed Rafiq, center, comforts his wife Noora Khatum and his children as they reach Teknaf, Bangladesh, Friday, Sept. 29, 2017. He trekked to Bangladesh as part of an exodus of a half million people from Myanmar, the largest refugee crisis to hit Asia in decades. But after climbing out of a boat on a creek on Friday, Rafiq could go no further. He collapsed onto a muddy spit of land cradling his wife in his lap, a limp figure so exhausted and so hungry she could no longer walk or even raise her wrists.: photo by Gemunu Amarasinghe/AP, 29 September 2017

He collapsed onto a muddy spit of land cradling his wife in his lap — a limp figure so exhausted and so hungry she could no longer walk or even raise her wrists.

The couple had no food, no money, no idea what to do next. Their two traumatized children huddled close beside them, unsure what to make of the country they had arrived in just hours earlier, in the middle of the night.

Rafiq said their third child, an 8-month-old boy, had been left behind. Buddhist mobs in Myanmar burned the child to death, he said, after setting their village ablaze while security forces stood idly by — part of a systematic purge of ethnic Rohingya Muslims from Buddhist-majority Myanmar that the United Nations has condemned as “a textbook example of ethnic cleansing.”

Five weeks after the mass exodus began on Aug. 25, the U.N. says the total number of arrivals in Bangladesh has now topped 501,000.

And still, they keep coming.

“We don’t ever want to go back,” a stunned Rafiq said, describing his family’s ordeal as Bangladeshi volunteers stuffed a small wad of cash into his hand and gave their children biscuits. Another man offered a bottle of water, and Rafiq poured some into his wife’s mouth as she lay in his arms, staring blankly at the sky.

“This is not our home. It is not our country,” Rafiq said. “But at least, we feel safe here.”

Not all those who have fled over the last few desperate weeks have survived. The International Organization for Migration said more than 60 refugees were confirmed dead or missing and presumed dead after one vessel capsized on rough seas in the area Thursday.

The crisis began when a Rohingya insurgent group launched attacks with rifles and machetes on a series of security posts in Myanmar on Aug. 25, prompting the military to launch a brutal round of “clearance operations” in response.

Those fleeing have described indiscriminate attacks by security forces and Buddhist mobs, including monks, as well as killings and rapes.

While the international community has condemned the violence and called on Myanmar to protect the Rohingya, Sufi Ullah, a police officer in Teknaf, said nothing has changed.

“We’re seeing them come across whenever they get the chance,” Ullah said.

“They’re hiding themselves in the forests and hills (inside Myanmar) in the daytime. And when they get the chance, they run. The Myanmar army is putting pressure on them. These people are afraid.”

Ullah said several thousand new refugees arrived by boat in Bangladesh on Friday, and authorities were not expecting the flow to let up any time soon.

On Friday, dramatic scenes played out over and over as hordes of Rohingya who had crossed into Bangladesh overnight tried to make their way further inland. They trudged out of boats and through mud that in some places was knee deep. Men carried babies and old women on their backs. Everyone was exhausted.

Sonabanu Chemmon was among those too weak to walk. Her son-in-law had carried her to one of Bangladeshi’s inland creeks, near Shah Porir Dip. But he then abandoned her along with several of her adult daughters.

Asked why, Chemmon covered her eyes as tears fell down her cheeks.

“He said he had carried me far enough, that he couldn’t carry me anymore,” she said. “He told me, ‘You can make it from here. I have to look after my own children.’”

Chemmon was finally helped by several Bangladeshis who are among a small army of local citizenry collecting donations, food and clothing, and handing it out to desperate new arrivals.

“Some of these people haven’t eaten or slept in days. They’re so weak, they can’t even walk,” said Mohamed Ismail, a Bangladeshi volunteer who traveled here from the city of Chittagong.

“I’ve never seen anything like it. They have nothing. It’s painful to watch,” he said, turning away, overcome with emotion. “Bangladesh is not rich, but we have to help.”

Karim Elguindi, who heads the U.N. World Food Program office in Cox’s Bazar, described the scene Friday as “distressing.”

“There’s more and more people coming and there’s not enough space in the existing camps” to accommodate them, said Elguindi, who was touring the area after hearing a new influx was underway. “I don’t know how many Rohingya are left in Myanmar ... but there’s more on the way.”

Elguindi said many of the refugees had been traveling for five days or more, and many were not carrying food during the journey. “These people are very vulnerable, very hungry ... they need shelter, they need water.”

Myanmar’s government, led by Nobel Peace Prize winner Aung San Suu Kyi, and its still powerful military do not allow independent media free access to northern Rakhine state, from where the Rohingya are fleeing. While fires are no longer visible from the Bangladeshi border, some refugees told The Associated Press that their homes had been burned as recently as two days ago.

Rafiq said he and his wife, Noor Khatum, fled their home in the Maungdaw village in Khai Dar Para in the first week of September, after police and soldiers moved in and Buddhist mobs, including monks, set fire to homes there in the middle of the night.

Rafiq managed to get his 5-year-old daughter out, while his wife carried their 2-year-old son. But their house, made of wood and sticks, burned quickly, collapsing on their baby boy before they could save him.

After fleeing, they took shelter with relatives in another village, but several days later that village, too, was torched by Buddhist mobs. Rafiq and his family then hid with others in an abandoned house near the border for two weeks, but had no money to pay boatmen to take them across the Naf River to Bangladesh.

So for two days, Rafiq helped other families escape, carrying them and their goods in exchange for amounts of cash. On Friday at 3 a.m., his own family finally made it out.

Now, in Bangladesh, a far more uncertain chapter of their lives has begun.

“We don’t know where we will go,” Rafiq said forlornly, as a long line of families trudged single file toward the town of Teknaf, where authorities were assessing the new arrivals and trucking them to camps further north. “We have nothing. We don’t know what we will do.”

A newly arrived Rohingya Muslim Mohamed Rafiq, center, comforts his wife Noora Khatum and his children as they reach Teknaf, Bangladesh, Friday, Sept. 29, 2017. He trekked to Bangladesh as part of an exodus of a half million people from Myanmar, the largest refugee crisis to hit Asia in decades. But after climbing out of a boat on a creek on Friday, Rafiq could go no further. He collapsed onto a muddy spit of land cradling his wife in his lap, a limp figure so exhausted and so hungry she could no longer walk or even raise her wrists.: photo by Gemunu Amarasinghe/AP, 29 September 2017

A Rohingya Muslim woman who just crossed the border from Myanmar into Bangladesh puts her head down and cries in Teknaf, Bangladesh, Friday, Sept. 29, 2017. More than a month after Myanmar’s refugees began spilling across the border, the U.N. says more than half a million have arrived.: photo by Gemunu Amarasinghe/AP, 29 September 2017

A Rohingya Muslim man from Myanmar carries an elderly woman after they crossed the border into Bangladesh from Myanmar, in Teknaf, Bangladesh, Friday, Sept. 29, 2017. More than a month after Myanmar’s refugees began spilling across the border, the U.N. says more than half a million have arrived.: photo by Gemunu Amarasinghe/AP, 29 September 2017

Rohingya Muslims walk towards a camp for refugees after crossing the boder from Myanmar into Bangladesh in Teknaf, Friday, Sept. 29, 2017. More than a month after Myanmar’s refugees began spilling across the border, the U.N. says more than half a million have arrived.: photo by Gemunu Amarasinghe/AP, 29 September 2017

A newly arrived Rohingya Muslim boy from Myanmar walks towards a camp for refugees in Teknaf, Bangladesh, Friday, Sept. 29, 2017. More than a month after Myanmar’s refugees began spilling across the border, the U.N. says more than half a million have arrived.: photo by Gemunu Amarasinghe/AP, 29 September 2017

Tears roll down the cheek of a Rohingya Muslim woman who crossed over the border from Myanmar into Bangladesh in Teknaf, Friday, Sept. 29, 2017. More than a month after Myanmar’s refugees began spilling across the border, the U.N. says more than half a million have arrived.: photo by Gemunu Amarasinghe/AP, 29 September 2017

Bangladeshi volunteers help a newly arrived Rohingya Muslim woman Sonabanu Chemmon at Teknaf, Bangladesh, Friday, Sept. 29, 2017. Chemmon was among those too weak to walk. Her son-in-law had carried her to one of Bangladeshi’s inland creeks, near Shah Porir Dip. But he then abandoned her along with several of her adult daughters. Chemmon was finally helped by several Bangladeshis who are among a small army of local citizenry who are collecting donations, food and clothing and handing it out to desperate new arrivals.: photo by Gemunu Amarasinghe/AP, 29 September 2017

A Bangladeshi volunteer carries a newly arrived elderly Rohingya Muslim woman Sonabanu Chemmon and heads towards a camp for refugees in Teknaf, Bangladesh, Friday, Sept. 29, 2017. Chemmon was among those too weak to walk. Her son-in-law had carried her to one of Bangladeshi’s inland creeks, near Shah Porir Dip. But he then abandoned her along with several of her adult daughters. Chemmon was finally helped by several Bangladeshis who are among a small army of local citizenry who are collecting donations, food and clothing and handing it out to desperate new arrivals.: photo by Gemunu Amarasinghe/AP, 29 September 2017

A newly arrived Rohingya Muslim boy carries a bottle of water and a pair of sandals and runs past a muddy patch to a camp for refugees in Teknaf, Bangladesh, Friday, Sept. 29, 2017. More than a month after Myanmar’s refugees began spilling across the border, the U.N. says more than half a million have arrived.: photo by Gemunu Amarasinghe/AP, 29 September 2017

A Rohingya Muslim man carries an elderly woman and walks towards a camp for refugees after crossing over the border from Myanmar into Bangladesh in Teknaf, Bangladesh, Friday, Sept. 29, 2017. More than a month after Myanmar’s refugees began spilling across the border, the U.N. says more than half a million have arrived. : photo by Gemunu Amarasinghe/AP, 29 September 2017

A Rohingya Muslim from Myanmar holds a hen on his lap as

he travels on a wooden boat after crossing over from Myanmar into

Bangladesh in Teknaf, Bangladesh, Friday, Sept. 29, 2017. More than a

month after Myanmar’s refugees began spilling across the border, the

U.N. says more than half a million have arrived.: photo by Gemunu Amarasinghe/AP, 29 September 2017

Rohingya Muslims carry a sick woman in a basket as they

walk towards a camp for refugees after crossing the border from Myanmar

into Bangladesh in Teknaf, Bangladesh, Friday, Sept. 29, 2017. More than

a month after Myanmar’s refugees began spilling across the border, the

U.N. says more than half a million have arrived. The prejudice and

hostility that Rohingya Muslims face in Myanmar stretch beyond the

country’s notoriously brutal security forces to a general population

receptive to an often-virulent form of Buddhist nationalism that has

seen a resurgence since the end of military rule.: photo by Gemunu Amarasinghe/AP, 29 September 2017

A Bangladeshi volunteer carries a Rohingya Muslim woman

Sonabanu Chemmon off a boat after she arrived with a group of other

Rohingya at Teknaf, Bangladesh, Friday, Sept. 29, 2017. Chemmon was

among those too weak to walk. Her son-in-law had carried her to one of

Bangladeshi’s inland creeks, near Shah Porir Dip. But he then abandoned

her along with several of her adult daughters. Chemmon was finally

helped by several Bangladeshis who are among a small army of local

citizenry who are collecting donations, food and clothing and handing it

out to desperate new arrivals.: photo by Gemunu Amarasinghe/AP, 29 September 2017

A Rohingya Muslims girl rests on a pile of bags, as she waits with others to walk towards a camp for refugees after crossing into Bangladesh from Myanmar, in Teknaf, Bangladesh, Friday, Sept. 29, 2017. More than a month after Myanmar’s refugees began spilling across the border, the U.N. says more than half a million have arrived. The prejudice and hostility that Rohingya Muslims face in Myanmar stretch beyond the country’s notoriously brutal security forces to a general population receptive to an often-virulent form of Buddhist nationalism that has seen a resurgence since the end of military rule.: photo by Gemunu Amarasinghe/AP, 29 September 2017

Dear @realDonaldTrump,

While you tweet from your golf club, the Mayor of San Juan is saving lives. You've done NOTHING.

Sincerely,

America: image via Michael Skolnik @Michael Skolnik, 20 September 2017

6:53 p.m.

San Juan

“Solitude kills,” Ana Luz Pérez said, breaking down in tears at her small glass dining table.: image via The New York Times @nytimes, 30 September 2017

President Donald Trump speaks to the media as he walks to

Marine One as he departs the White House, Friday, Sept. 29, 2017, in

Washington. Trump is en route to Bedminster, N.J.: photo by Alex Brandon/AP, 29 September 2017

Trump lashes out at San Juan mayor who begged for more help: Jill Colvin, AP, 30 September 2017

BRANCHBURG, N.J. (AP) — President Donald Trump on Saturday lashed out

at the mayor of San Juan and other officials in storm-ravaged Puerto

Rico, contemptuous of their claims of a laggard U.S. response to the

natural disaster that has imperiled the island’s future.

“Such poor leadership ability by the Mayor of San Juan, and others in

Puerto Rico, who are not able to get their workers to help,” Trump said

in a series of tweets a day after the capital city’s mayor appealed for

help “to save us from dying.”

“They want everything to be done for them when it should be a community effort,” Trump wrote from his New Jersey golf club.

The tweets were a biting attack on the leader of a community in

crisis. After 10 days of desperation, with many still unable to access

essentials including food and water, San Juan Mayor Carmen Yulin Cruz

accused the Trump administration Friday of “killing us with the

inefficiency” after Hurricane Maria. She implored the president, who is

set to visit the U.S. territory on Tuesday, to “make sure somebody is in

charge that is up to the task of saving lives.”

“I am begging, begging anyone that can hear us, to save us from

dying,” Cruz said at a news conference, her voice breaking with rage.

It was an unusually pointed rebuke from the president in the heat of a

disaster — a time when leaders often put aside partisan differences in

the name of solidarity. But it was a reminder of Trump’s unrelenting

penchant for punching back against critics, whatever the circumstances.

Trump has said he’s doing everything possible to help the “great

people of PR!” and has pledged to spare no effort to help the island

recover from Maria’s ruinous aftermath. He has also repeatedly applauded

his government’s recovery efforts, saying military personnel and first

responders have done “an amazing job,” despite the significant

logistical challenges.

Thousands more Puerto Ricans have received water and rationed food as

an aid bottleneck has begun to ease. But many, especially outside the

capital, remain desperate for necessities, including water, power and

fuel.

Trump’s administration has tried in recent days to combat the

perception that he failed to quickly grasp the magnitude of Maria’s

destruction and has given the U.S. commonwealth less attention than he’d

bestowed on states like Texas, Louisiana and Florida after they were

hit by hurricanes Harvey and Irma. Trump had repeatedly praised the

residents of those states as strong and resilient, saying at one point

that Texas could “handle anything.”

Administration officials have held numerous press conferences

providing updates on relief efforts and Trump on Saturday spoke by phone

from New Jersey with FEMA Administrator Brock Long, Puerto Rico’s

governor, Ricardo Rosselló, and other several other local officials.

But after a week of growing criticism, the president’s patience appears to be waning.

“The Mayor of San Juan, who was very complimentary only a few days

ago, has now been told by the Democrats that you must be nasty to

Trump,” the president charged, without substantiation.

FEMA administrator Brock Long also piled on: “The problem that we

have with the mayor unfortunately is that unity of command is ultimately

what’s needed to be successful in this response,” he said, requesting

that she report to a joint field office.

Cruz declined to engage in the tit-for-tat, instead calling for a

united focus on the people who need help. “The goal is one: saving

lives. This is the time to show our ‘true colors.’

We cannot be

distracted by anything else,” she tweeted, along with photos of herself

meeting with residents and rescue workers, wading hip-deep through a

flooded street and comforting an elderly woman.

After a day of tweets criticizing the news media, Trump seemed to

echo the sentiment: “We must all be united in offering assistance to

everyone suffering in Puerto Rico and elsewhere in the wake of this

terrible disaster.”

Trump’s Saturday tweets are the latest example of his insistence on

“punching back,” even against those with far less power. After a deadly

terror attack in London in June, for instance, Trump singled out London

Mayor Sadiq Khan, suggesting he wasn’t taking the attacks seriously

enough.

Natural disasters sometimes bring moments of rare bipartisan

solidarity. In the aftermath of Superstorm Sandy, which wreaked havoc

along the East Coast in 2012, New Jersey’s Republican governor, Chris

Christie, praised Democratic President Barack Obama for his personal

attention and compassion at a joint press conference. Still, the fight

over relief money became politicized and contentious, with numerous

Republicans voting against a delayed relief bill.

In the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina, tensions between local and

federal officials also ran high. Then-New Orleans Mayor Ray Nagin

pleaded with the government to send help in sometimes colorful terms,

while Terry Ebbert, the city’s Homeland Security director, called relief

efforts a “national disgrace.”

Kate Hale, Dade County’s emergency management chief during Hurricane

Andrew, also blasted FEMA’s response in an angry news conference that

was credited with spurring federal government action.

“I wasn’t there to criticize; I was there to beg for help,” she said.

“I was terrified of what was going to happen to people that otherwise

could have been saved. It was never my intention to criticize; it was my

intention to cry for help, my intention to beg for help. And it came

out like it did, because it just does.”

“We were all at the end of our rope,” she said. “We didn’t know what else to do.”

She called Cruz’s remarks a passionate outcry “from a woman who loves

her community and the people in it, has watched it be destroyed and is

now watching people die.”

President Trump defended his administration’s response to

the devastation in Puerto Rico following Hurricane Maria. He also said

some “very bad things” happened to American diplomats who were harmed by

unexplained health “attacks” in Cuba.: photo by AP, 29 September 2017

“We are dying here. And I cannot fathom the thought that the greatest nation in the world cannot figure out the logistics for a small island of 100 miles by 35 miles. So, mayday, we are in trouble.

Carmen Yulín Cruz, the mayor of San Juan. Ms. Cruz had criticized the Trump administration on Friday for its rosy comments on the state of hurricane relief efforts in Puerto Rico, and the president responded Saturday morning.: photo by Victor J. Blue for The New York Times, 30 September 2017

As emergency workers and troops struggled to restore basic services in a commonwealth with no electricity and limited fuel and water, Mr. Trump spent the day at his New Jersey golf club, blasting out Twitter messages defending his response to the storm and repeatedly assailing the capital’s mayor, Carmen Yulín Cruz, and the news media.

“The Mayor of San Juan, who was very complimentary only a few days ago, has now been told by the Democrats that you must be nasty to Trump,” the president wrote on Twitter. “Such poor leadership ability by the Mayor of San Juan, and others in Puerto Rico, who are not able to get their workers to help.”

Mr. Trump said the people of Puerto Rico should not depend entirely on the federal government. “They want everything to be done for them when it should be a community effort,” he wrote. “10,000 Federal workers now on Island doing a fantastic job. The military and first responders, despite no electric, roads, phones etc., have done an amazing job. Puerto Rico was totally destroyed.”

The president’s stream of Twitter bolts appeared repeatedly over the course of 12 hours and touched off a furious day of recriminations that fueled questions about his leadership during the crisis. Although Mr. Trump earned generally high marks for his handling of hurricanes that struck Texas and Florida recently, he has been sharply criticized for being slow to sense the magnitude of the damage in Puerto Rico, an American territory, and project urgency about helping.

He has explained that the challenges are different because Puerto Rico is “an island surrounded by water — big water, ocean water,” as he put it on Friday, but in recent days he has stepped up his public statements and dispatched a three-star general to take over the response. Mr. Trump’s aggressive Twitter messages on Saturday were in keeping with how he has acted during other moments of crisis, notably when he assailed the mayor of London, who is Muslim, after a terrorist attack, asserting that he did not take the threat seriously enough.

In the case of Ms. Cruz, Mr. Trump took her outcry as a personal assault on him. While other presidents generally ignore most of the criticism they invariably attract, Mr. Trump is not one to let anything go unanswered. In one of his books, he titled a chapter “Revenge,” writing that “when someone crosses you, my advice is ‘Get even!’ If you do not get even, you are just a schmuck!”

His attack on Ms. Cruz on Saturday was amplified by a top aide, who retweeted a message she had written during last year’s campaign endorsing Hillary Clinton over Mr. Trump. “@realDonaldTrump hater, the Mayor of San Juan — is the perfect example of an opportunistic politician,” wrote Dan Scavino Jr., the president’s social media director.

Responding to Mr. Trump’s tweets on Saturday, Ms. Cruz said she would not be distracted by “small comments” and denied that she was attacking the president at the behest of the Democrats. “Actually, I was asking for help,” she told MSNBC. “I wasn’t saying anything nasty about the president.”

She pointed to comments made on Friday by Lt. Gen. Jeffrey Buchanan, who is leading the response effort and who said on Friday that he did not have enough troops and equipment. “So who am I?” Ms. Cruz asked. “I’m just a little mayor from the capital city of San Juan. This is a three-star general telling the world that right now he does not have the appropriate means and tools to take care of the situation.”

The attacks on the mayor generated a backlash from celebrities and others who noted that the president was spending the weekend in the comfort of his golf club while the mayor was struggling to help her constituents on an island with no power. “She has been working 24/7,” Lin-Manuel Miranda, the creator of “Hamilton,” the hit Broadway musical, wrote on Twitter. “You have been GOLFING. You’re going straight to hell. Fastest golf cart you ever took.”

Lady Gaga, who has twice as many Twitter followers as the president, said that “it’s clear where the ‘poor leadership’ lies @realDonaldTrump” and added that he was “not helping PR because of the electoral votes u need to be re-elected.” As an American territory, Puerto Rico does not have votes in the Electoral College, which determines the presidency every four years.

Russel L. Honoré, the retired lieutenant general who took over the response to Hurricane Katrina in 2005 after an initially inadequate federal effort, also noted the president’s weekend retreat. “The mayor’s living on a cot, and I hope the president has a good day at golf,” he said on CNN.

The president was out of sight on Saturday, secluded at his club in Bedminster, N.J., miles away from the pool of journalists who follow him. Aides would not say whether he went golfing, although they said he had telephone calls scheduled with Puerto Rico’s governor and the head of the Federal Emergency Management Agency.

Ms. Cruz became a powerful voice of grievance on Friday when she went on television to plead for help and reject assertions by the Trump administration about how well it was responding. She was incensed by comments made by Elaine Duke, the acting secretary of Homeland Security, who had said on Thursday that it was “really a good news story in terms of our ability to reach people and the limited number of deaths” from the hurricane.

“This is, damn it, this is not a good news story,” Ms. Cruz said on CNN. “This is a ‘people are dying’ story. This is a ‘life or death’ story. This is ‘there’s a truckload of stuff that cannot be taken to people’ story. This is a story of a devastation that continues to worsen.”

Ms. Duke traveled to Puerto Rico on Friday and tried to smooth things over, agreeing that the situation on the ground was “not satisfactory.”

General Buchanan, who arrived in Puerto Rico on Thursday to take over the hurricane response, said on Friday that he needed more personnel and resources. “The answer is no, it’s not enough and we’re bringing more in,” he said on CNN.

Ms. Cruz, a member of the Popular Democratic Party, which advocates maintaining the island’s commonwealth status, was unmollified and went back on CNN on Friday night to continue her pleas for help wearing a black T-shirt that said, “Help Us, We Are Dying.”

“We’re dying here,” she told the anchor Anderson Cooper. “We truly are dying here. And I keep saying it, SOS. If anyone can hear us, if Mr. Trump can hear us, let’s just get it over with and get the ball rolling.”

At least 16 people have died in Puerto Rico in the aftermath of Maria, which came soon after Hurricane Irma, although that number could rise. The island has a population of 3.4 million people, roughly the same as Connecticut. In addition to appointing General Buchanan, the Trump administration has waived the Jones Act, a maritime commerce statute that was seen as a hindrance to relief efforts.

Mr. Trump plans to travel to Puerto Rico with his wife, Melania, on Tuesday, nearly two weeks after the hurricane slammed into the island but the earliest he said he could get there without diverting resources from the rescue and recovery efforts. He said on Saturday that he would also “hopefully be able to stop at the U.S. Virgin Islands,” where 100,000 American citizens are also struggling to recover from storm devastation.

The president dismissed complaints about the federal response as distortions from the news media. “Fake News CNN and NBC are going out of their way to disparage our great First Responders as a way to ‘get Trump,’” he wrote. “Not fair to FR or effort!”

Hours later, he added: “Results of recovery efforts will speak much louder than complaints by San Juan Mayor. Doing everything we can to help great people of PR!”

8:48 a.m. San Juan. Elizabeth Parrilla turned the corner at Calle Loíza and trudged quietly down the dead-end road leading to her home of 50 years on Calle Pablo Andino. Her wedges were beginning to get filthy from the damp foliage left behind by the waters that had inundated her street several days before.: photo by Victor J. Blue for The New York Times, 30 September 2017

7:44 a.m. Corozal. Three hundred cars and trucks were lined up on the shoulder of the highway just outside town. Another line of at least 100 cars had formed on the other side of the Ecomaxx gas station.: Kirsten Luce for The New York Times, 30 September 2017

9:05 a.m. Joey Ramos descended the stairs of his two-story home in water boots and swimming trunks. He carried a green electric saw and waded across the black waters that had flooded Calle Santa Cecilia. Ever since Hurricane Maria flooded the first floor of his house in Ocean Park, Mr. Ramos has been boxed in the second floor of his home, hunkered down with his wife and his four pitbull-mastiff mix dogs, which guard his house.: photo by Victor J. Blue for The New York Times, 30 September 2017

11:57 a.m. San Juan. In front of the pink and green, art deco facade of the Telégrafo building in Santurce, dozens of people checked their phones. The section of the street is one of the few spots on the island where residents can connect to free Wi-Fi.: photo by Victor J. Blue for The New York Times, 30 September 2017

3:08 p.m. Guayama. Three plainclothes security guards protect the Plaza Tu Supermarket, which is a mess of tangled metal, from potential burglars. “All the tire shops on the street were looted. They did it right in front of us and didn’t care,” said one guard, who would only give his first name, Albert. “You should have seen, there were tires rolling all down the street right to the projects.”: photo by Erika P. Rodriguez for The New York Times, 30 September 2017

4:19 p.m. Barrio Vietnam, Guaynabo. A man whose three houses were ravaged in this poor, informal coastal community salvages what he can from the wreckage and struggles to clean up.: photo by Victor J. Blue for The New York Times, 30 September 2017

Carmen Yulín Cruz, 30 September:

“We are dying here. And I cannot fathom the thought that the greatest nation in the world cannot figure out the logistics for a small island of 100 miles by 35 miles. So, mayday, we are in trouble.

“Fema [the Federal Emergency Management Administration] asks for documentation, I think we’ve given them enough documentation.

“They had the gall this morning – look at this [gestures to

two large binders filled with paper] – they had the gall this morning to

ask me: ‘What are your priorities, mayor?’

“Well, where have you been?

“And I have been very respectful of the Fema employees. I have been patient but we have no time for patience any more.

“So, I am asking the president of the United States to make sure somebody is in charge that is up to the task of saving lives.

“They were up the task in Africa when Ebola came over. They

were up to the task in Haiti [after the earthquake of 2010]. As they

should be. Because when it comes to saving lives we are all part of one

community of shared values.

“I will do what I never thought I was going to do: I am

begging. I am begging anyone that can hear us to save us from dying. If

anybody out there is listening to us, we are dying. And you are killing

us with the inefficiency and bureaucracy.

“We will make it with or without you because what stands behind me is all due to the generosity of other people.

“Again, this is what we got last night: four pallets of

water, three pallets of meals and 12 pallets of infant food. Which, I

gave them to Comerío, where people are drinking out of a creek.

“So I am done being polite. I am done being politically

correct. I am mad as hell because my people’s lives are at stake. And we

are but one nation. We may be small, but we are huge in dignity and

zealous for life.

“So I’m asking members of the press to send a mayday call

all over the world. We are dying here. And if we don’t stop and if we

don’t get the food and the water into people’s hands, what we we are

going to see is something close to a genocide.

“So, Mr Trump, I am begging you to take charge and save

lives. After all, that is one of the founding principles of the United

States of North America. If not, the world will see how we are treated

not as second-class citizens but as animals that can be disposed of.

Enough is enough.”

Carmen Yulín Cruz, the mayor of San Juan. Ms. Cruz had criticized the Trump administration on Friday for its rosy comments on the state of hurricane relief efforts in Puerto Rico, and the president responded Saturday morning.: photo by Victor J. Blue for The New York Times, 30 September 2017

Trump Lashes Out at Puerto Rico Mayor Who Criticized Storm Response: Peter Baker, The New York Times, 30 September 2017

WASHINGTON — President Trump lashed out at the mayor of San Juan on Saturday for

criticizing his administration's efforts to help Puerto Rico after Hurricane Maria, accusing her of “poor leadership” and implying

that the people of the devastated island were not doing enough to help

themselves.

As emergency workers and troops struggled to restore basic services in a commonwealth with no electricity and limited fuel and water, Mr. Trump spent the day at his New Jersey golf club, blasting out Twitter messages defending his response to the storm and repeatedly assailing the capital’s mayor, Carmen Yulín Cruz, and the news media.

“The Mayor of San Juan, who was very complimentary only a few days ago, has now been told by the Democrats that you must be nasty to Trump,” the president wrote on Twitter. “Such poor leadership ability by the Mayor of San Juan, and others in Puerto Rico, who are not able to get their workers to help.”

Mr. Trump said the people of Puerto Rico should not depend entirely on the federal government. “They want everything to be done for them when it should be a community effort,” he wrote. “10,000 Federal workers now on Island doing a fantastic job. The military and first responders, despite no electric, roads, phones etc., have done an amazing job. Puerto Rico was totally destroyed.”

The president’s stream of Twitter bolts appeared repeatedly over the course of 12 hours and touched off a furious day of recriminations that fueled questions about his leadership during the crisis. Although Mr. Trump earned generally high marks for his handling of hurricanes that struck Texas and Florida recently, he has been sharply criticized for being slow to sense the magnitude of the damage in Puerto Rico, an American territory, and project urgency about helping.

He has explained that the challenges are different because Puerto Rico is “an island surrounded by water — big water, ocean water,” as he put it on Friday, but in recent days he has stepped up his public statements and dispatched a three-star general to take over the response. Mr. Trump’s aggressive Twitter messages on Saturday were in keeping with how he has acted during other moments of crisis, notably when he assailed the mayor of London, who is Muslim, after a terrorist attack, asserting that he did not take the threat seriously enough.

In the case of Ms. Cruz, Mr. Trump took her outcry as a personal assault on him. While other presidents generally ignore most of the criticism they invariably attract, Mr. Trump is not one to let anything go unanswered. In one of his books, he titled a chapter “Revenge,” writing that “when someone crosses you, my advice is ‘Get even!’ If you do not get even, you are just a schmuck!”

His attack on Ms. Cruz on Saturday was amplified by a top aide, who retweeted a message she had written during last year’s campaign endorsing Hillary Clinton over Mr. Trump. “@realDonaldTrump hater, the Mayor of San Juan — is the perfect example of an opportunistic politician,” wrote Dan Scavino Jr., the president’s social media director.

Responding to Mr. Trump’s tweets on Saturday, Ms. Cruz said she would not be distracted by “small comments” and denied that she was attacking the president at the behest of the Democrats. “Actually, I was asking for help,” she told MSNBC. “I wasn’t saying anything nasty about the president.”

She pointed to comments made on Friday by Lt. Gen. Jeffrey Buchanan, who is leading the response effort and who said on Friday that he did not have enough troops and equipment. “So who am I?” Ms. Cruz asked. “I’m just a little mayor from the capital city of San Juan. This is a three-star general telling the world that right now he does not have the appropriate means and tools to take care of the situation.”

The attacks on the mayor generated a backlash from celebrities and others who noted that the president was spending the weekend in the comfort of his golf club while the mayor was struggling to help her constituents on an island with no power. “She has been working 24/7,” Lin-Manuel Miranda, the creator of “Hamilton,” the hit Broadway musical, wrote on Twitter. “You have been GOLFING. You’re going straight to hell. Fastest golf cart you ever took.”

Lady Gaga, who has twice as many Twitter followers as the president, said that “it’s clear where the ‘poor leadership’ lies @realDonaldTrump” and added that he was “not helping PR because of the electoral votes u need to be re-elected.” As an American territory, Puerto Rico does not have votes in the Electoral College, which determines the presidency every four years.

Russel L. Honoré, the retired lieutenant general who took over the response to Hurricane Katrina in 2005 after an initially inadequate federal effort, also noted the president’s weekend retreat. “The mayor’s living on a cot, and I hope the president has a good day at golf,” he said on CNN.

The president was out of sight on Saturday, secluded at his club in Bedminster, N.J., miles away from the pool of journalists who follow him. Aides would not say whether he went golfing, although they said he had telephone calls scheduled with Puerto Rico’s governor and the head of the Federal Emergency Management Agency.

Ms. Cruz became a powerful voice of grievance on Friday when she went on television to plead for help and reject assertions by the Trump administration about how well it was responding. She was incensed by comments made by Elaine Duke, the acting secretary of Homeland Security, who had said on Thursday that it was “really a good news story in terms of our ability to reach people and the limited number of deaths” from the hurricane.

“This is, damn it, this is not a good news story,” Ms. Cruz said on CNN. “This is a ‘people are dying’ story. This is a ‘life or death’ story. This is ‘there’s a truckload of stuff that cannot be taken to people’ story. This is a story of a devastation that continues to worsen.”

Ms. Duke traveled to Puerto Rico on Friday and tried to smooth things over, agreeing that the situation on the ground was “not satisfactory.”

General Buchanan, who arrived in Puerto Rico on Thursday to take over the hurricane response, said on Friday that he needed more personnel and resources. “The answer is no, it’s not enough and we’re bringing more in,” he said on CNN.

Ms. Cruz, a member of the Popular Democratic Party, which advocates maintaining the island’s commonwealth status, was unmollified and went back on CNN on Friday night to continue her pleas for help wearing a black T-shirt that said, “Help Us, We Are Dying.”

“We’re dying here,” she told the anchor Anderson Cooper. “We truly are dying here. And I keep saying it, SOS. If anyone can hear us, if Mr. Trump can hear us, let’s just get it over with and get the ball rolling.”

At least 16 people have died in Puerto Rico in the aftermath of Maria, which came soon after Hurricane Irma, although that number could rise. The island has a population of 3.4 million people, roughly the same as Connecticut. In addition to appointing General Buchanan, the Trump administration has waived the Jones Act, a maritime commerce statute that was seen as a hindrance to relief efforts.

Mr. Trump plans to travel to Puerto Rico with his wife, Melania, on Tuesday, nearly two weeks after the hurricane slammed into the island but the earliest he said he could get there without diverting resources from the rescue and recovery efforts. He said on Saturday that he would also “hopefully be able to stop at the U.S. Virgin Islands,” where 100,000 American citizens are also struggling to recover from storm devastation.

The president dismissed complaints about the federal response as distortions from the news media. “Fake News CNN and NBC are going out of their way to disparage our great First Responders as a way to ‘get Trump,’” he wrote. “Not fair to FR or effort!”

Hours later, he added: “Results of recovery efforts will speak much louder than complaints by San Juan Mayor. Doing everything we can to help great people of PR!”

8:48 a.m. San Juan. Elizabeth Parrilla turned the corner at Calle Loíza and trudged quietly down the dead-end road leading to her home of 50 years on Calle Pablo Andino. Her wedges were beginning to get filthy from the damp foliage left behind by the waters that had inundated her street several days before.: photo by Victor J. Blue for The New York Times, 30 September 2017

7:44 a.m. Corozal. Three hundred cars and trucks were lined up on the shoulder of the highway just outside town. Another line of at least 100 cars had formed on the other side of the Ecomaxx gas station.: Kirsten Luce for The New York Times, 30 September 2017

9:05 a.m. Joey Ramos descended the stairs of his two-story home in water boots and swimming trunks. He carried a green electric saw and waded across the black waters that had flooded Calle Santa Cecilia. Ever since Hurricane Maria flooded the first floor of his house in Ocean Park, Mr. Ramos has been boxed in the second floor of his home, hunkered down with his wife and his four pitbull-mastiff mix dogs, which guard his house.: photo by Victor J. Blue for The New York Times, 30 September 2017

11:57 a.m. San Juan. In front of the pink and green, art deco facade of the Telégrafo building in Santurce, dozens of people checked their phones. The section of the street is one of the few spots on the island where residents can connect to free Wi-Fi.: photo by Victor J. Blue for The New York Times, 30 September 2017

3:08 p.m. Guayama. Three plainclothes security guards protect the Plaza Tu Supermarket, which is a mess of tangled metal, from potential burglars. “All the tire shops on the street were looted. They did it right in front of us and didn’t care,” said one guard, who would only give his first name, Albert. “You should have seen, there were tires rolling all down the street right to the projects.”: photo by Erika P. Rodriguez for The New York Times, 30 September 2017

4:19 p.m. Barrio Vietnam, Guaynabo. A man whose three houses were ravaged in this poor, informal coastal community salvages what he can from the wreckage and struggles to clean up.: photo by Victor J. Blue for The New York Times, 30 September 2017

4:53 p.m. Utuado. Out in the countryside, on the

west bank of the Vivi River, the remaining chunk of a bridge washed away

by Maria juts violently and jaggedly, toward the east, like a broken

promise. There, two young women in

exercise gear stepped carefully off the broken bridge and descended a

homemade wooden ladder, some 40 feet up. They dropped onto a big pile of

debris and then crossed the knee-high waters to the opposite bank. Kayshla Rodríguez, 24, clambered up the east bank with her best friend, Mireli Mari, 27. Ms. Rodríguez’s parents owned one

of the houses on the east bank and were now stranded by the broken

bridge. There was no cell service here, and there was no way for her to

call her parents from her home in Mayagüez. So she drove here with Ms. Mari, a

three-hour journey with the post-hurricane traffic. When they finally

got to the house, and Ms. Rodríguez finished hugging her parents, she

learned that they had water from a spring at the top of the mountain and

enough food for a while. Her mother, Marilyn Luciano, 49, offered them

something to eat, but the daughter declined. “You need it more than I

do,” she said. Her father advised her to cross

back over the river before it rose too high. Reluctantly the two women

said their goodbyes, hopped in a white sedan and began the long drive

back.: photo by Kirsten Luce for The New York Times, 30 September 2017

6:23 p.m. Arecibo. Luis Rodríguez Perez, 28, sat

under a freeway overpass, making a video call to his brother in Buffalo,

N.Y. His wife was a few feet away, in the passenger seat of their

sedan. Mr. Rodríguez Perez lives in the

country, about 40 minutes from Arecibo. He had come to this overpass,

where he could get a faint cell signal, to call his brother and ask him

if he could find a ticket from Puerto Rico to Buffalo. This time, at

least, his brother found nothing.: photo by Kirsten Luce for The New York Times, 30 September 2017

6:53 p.m. San Juan. “Once night falls, you won't see me outside,” said Ana Luz Pérez at her tidy apartment at the Luis Lloréns Torres housing project, the largest in Puerto Rico. It has 140 buildings and is plagued by crime.She ran through her options for light in the gloom of her apartment. She decided to conserve the two candles she had left and instead used the remaining gas in her green camping lantern. She turned the knob of the gaslight, and the light flickered, bringing the shadows in the kitchen to life. The rice with ham and sausage she had cooked for her boyfriend earlier in the day were growing cold on a small stove connected to a white gas tank on the floor. She turned on the stove to warm the meal. “It's the last tank left,” Ms. Pérez said. "We didn't know it was going to be so difficult." The blackout had given Ms. Pérez plenty of sleepless nights. She spends much of the time smoking cigarettes on her balcony or splashing her face with cool water. She’s up by 4 a.m. She thinks of her four children, ages 21 to 27, living in the Bronx. She worries about her mother, who is 60 and has cancer.“Solitude kills,” she said, breaking down in tears at her small glass dining table. Over the cacophony of barking dogs, her boyfriend, Carlos Rivera, climbed the stairs to her apartment. As his shadow grew bigger by her apartment door, Ms. Pérez did not attempt to hide her tears.: photo by Victor J. Blue for The New York Times, 30 September 2017

6:56 p.m. Arecibo. A long line formed to buy ice in Arecibo.: photo by Kirsten Luce for The New York Times, 30 September 2017

7:08 p.m. San Juan. Residents of the the Luis Lloréns Torres housing project watched a television hooked up to a car battery in San Juan on Wednesday.: photo by Victor J. Blue for The New York Times, 30 September 2017

2:30 a.m. Ponce. The Tropical Ice company does not open until 7 a.m., but already people were lined up outside. They brought lawn chairs, books and playing cards. Some brought blankets. They clearly aimed to spend the night, and plenty of them were already fast asleep. Roberto Gallego, 69, was first, an impressive feat in a row of people at least 100 deep. “11 o’clock at night!” he proudly exclaimed when asked what time one had to arrive at the ice factory to be first in line for two $1.50 bags of watery ice. Ice was not the only thing he was anticipating. Mr. Gallego was also anxious for the airports to reopen. “This changed my life,” he said. “I’m going to Orlando.”: photo by Erika P. Rodriguez for The New York Times, 30 September 2017

5:28 a.m. San Juan. There’s an expression in Puerto Rico: “Hay que echar pa’ lante.” It roughly translates to “Gotta move forward.” It is an expression of optimism in the face of adversity, which Puerto Rico had in abundance even before Maria. The storm threw Puerto Rico into the darkest, most hellish abyss it has seen in generations. Maybe it would be naïve to think that a sustained dose of “Hay que echar pa’ lante” is enough for the island and its people to make it through. But it would be a misunderstanding of Puerto Rico’s people and culture not to factor it in.: photo by Victor J. Blue for The New York Times, 30 September 2017

. Joey Ramos stays to protect his home from looters.: photo by Victor J. Blue for The New York Times, 30 September 2017

A village street, Ponce

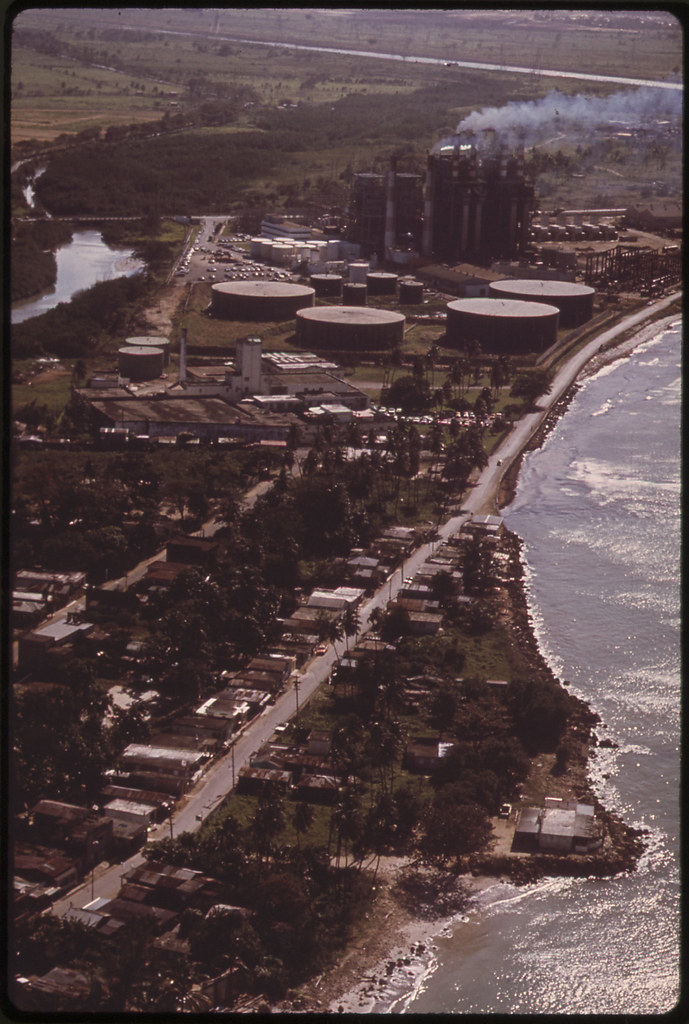

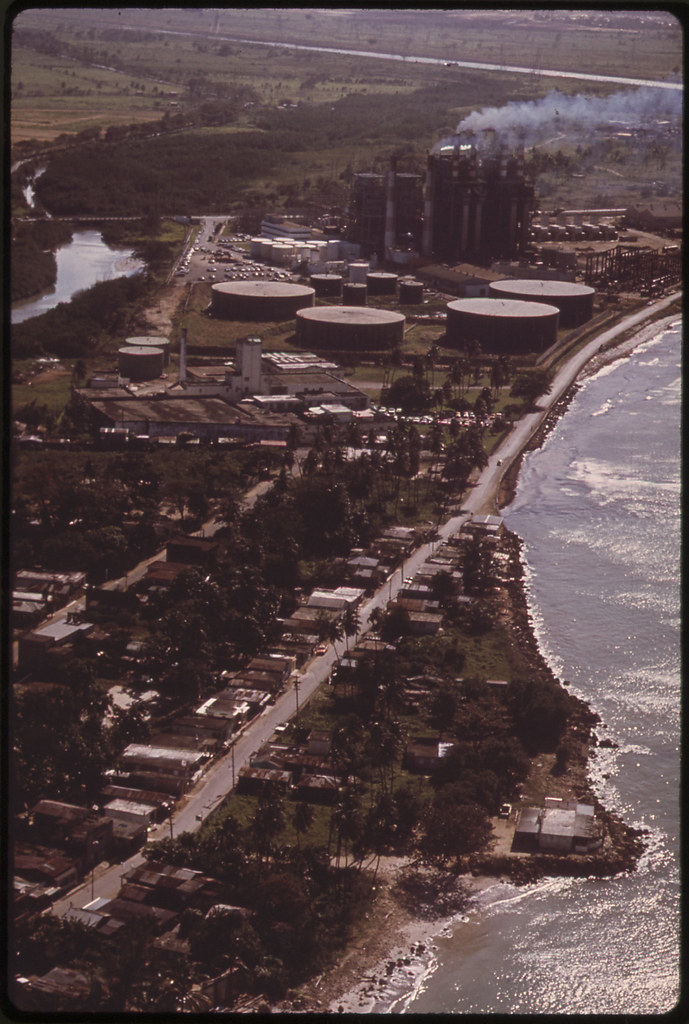

Sugar cane field and refinery, Ponce

Petrochemical plant in coastal area, Ponce

Oil refinery in the sunset, Ponce

Oil pipeline on the beach

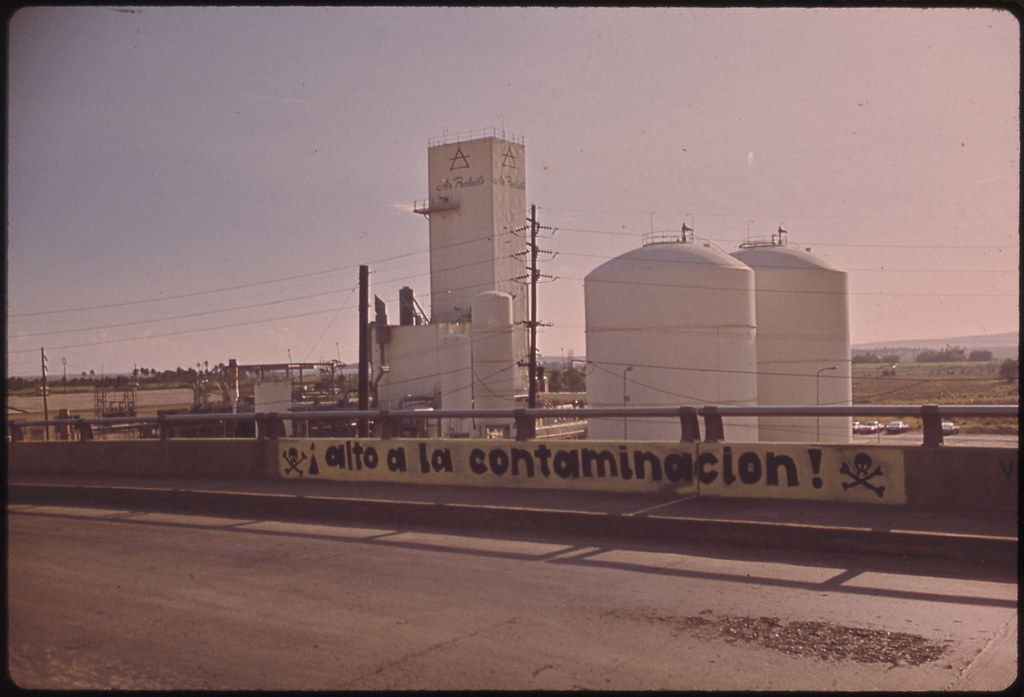

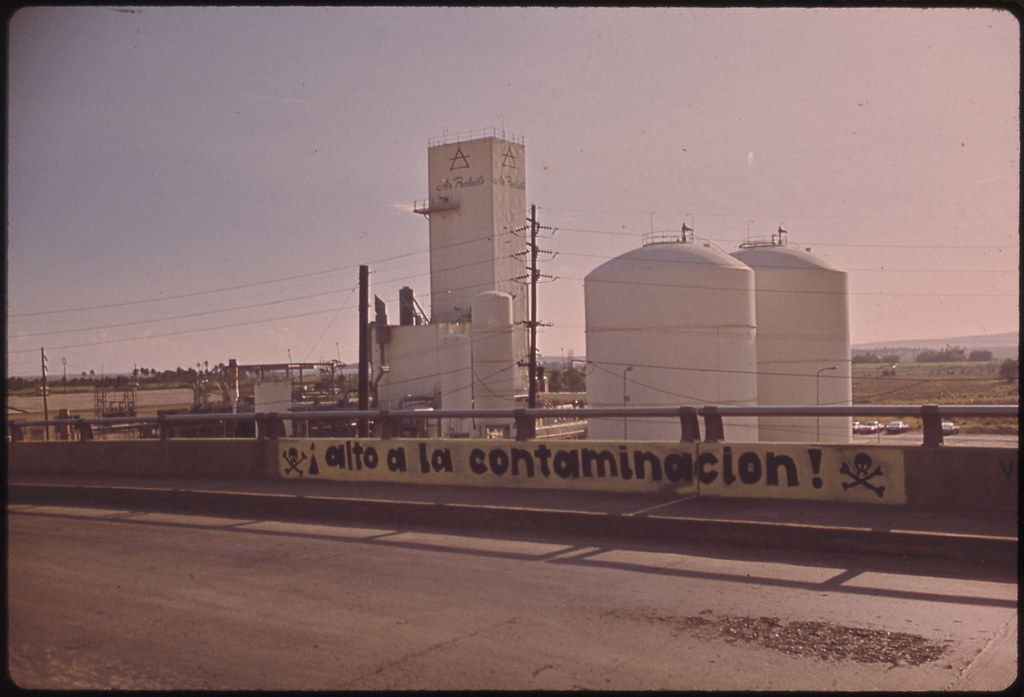

Sign on bridge near PPG plant protesting air pollution, Ponce

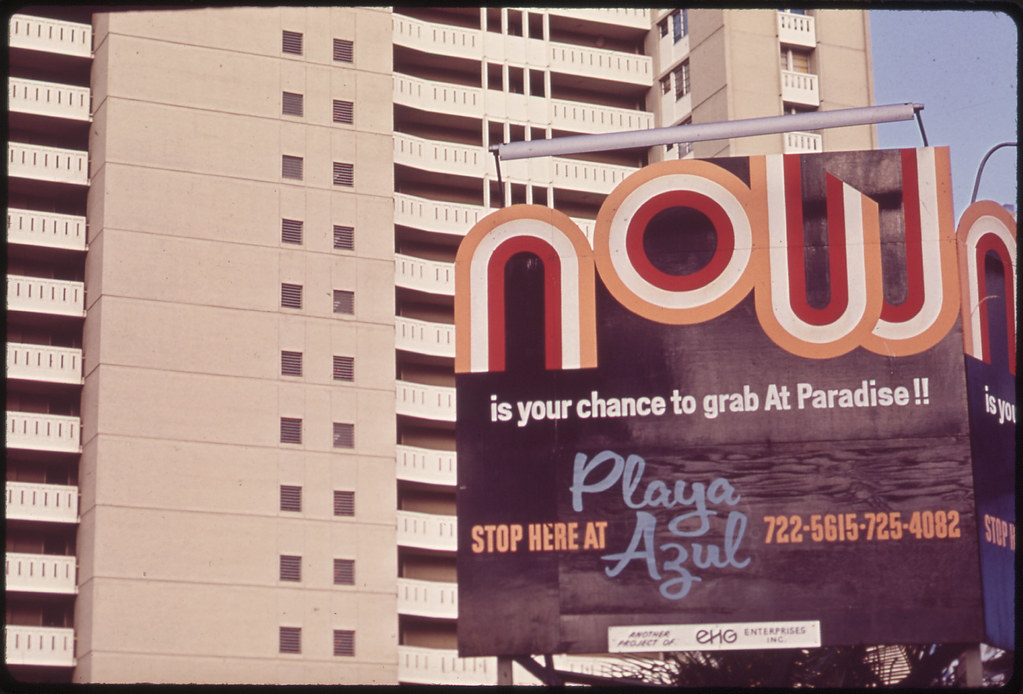

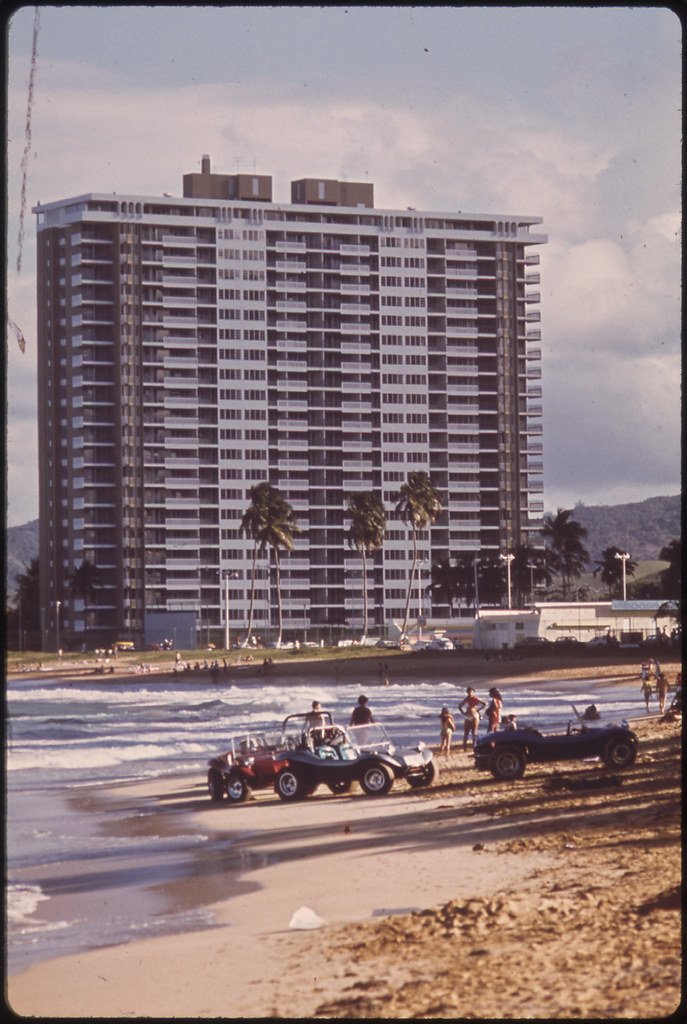

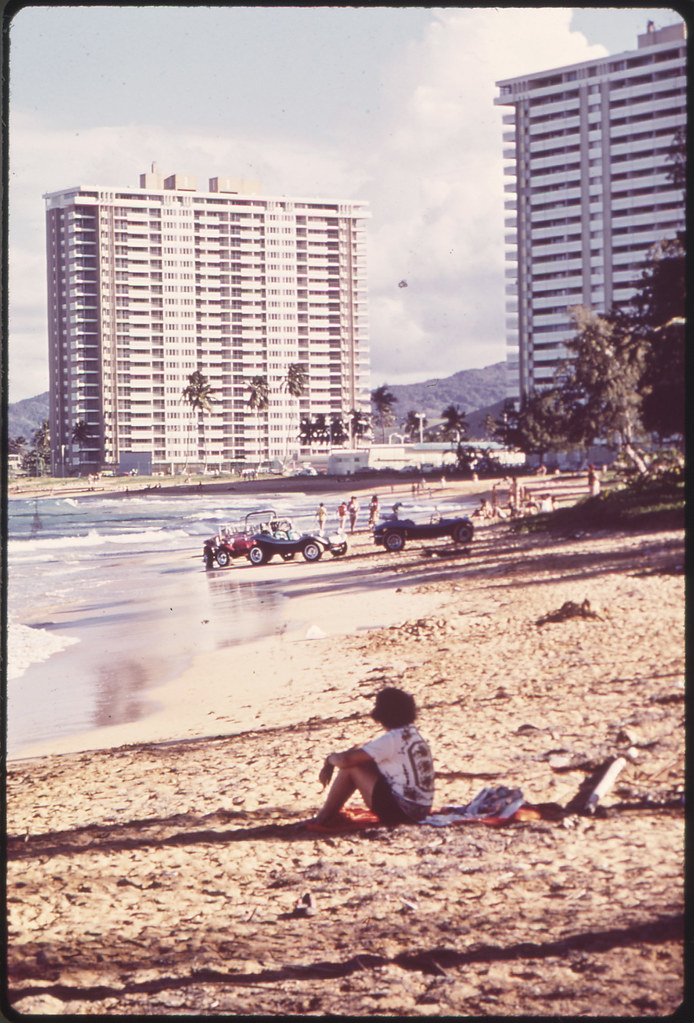

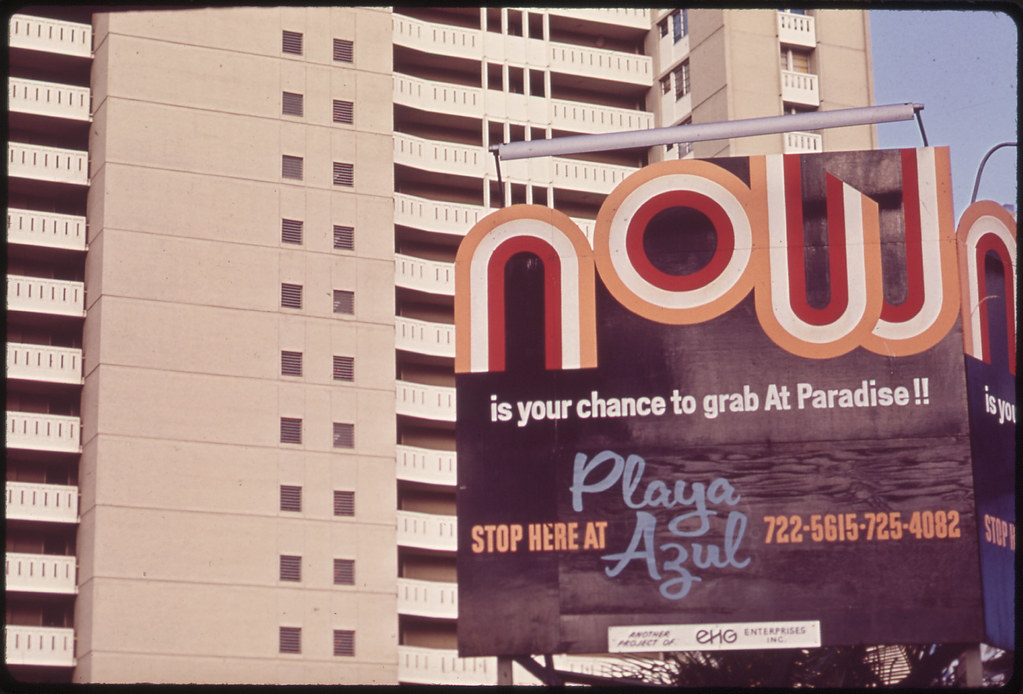

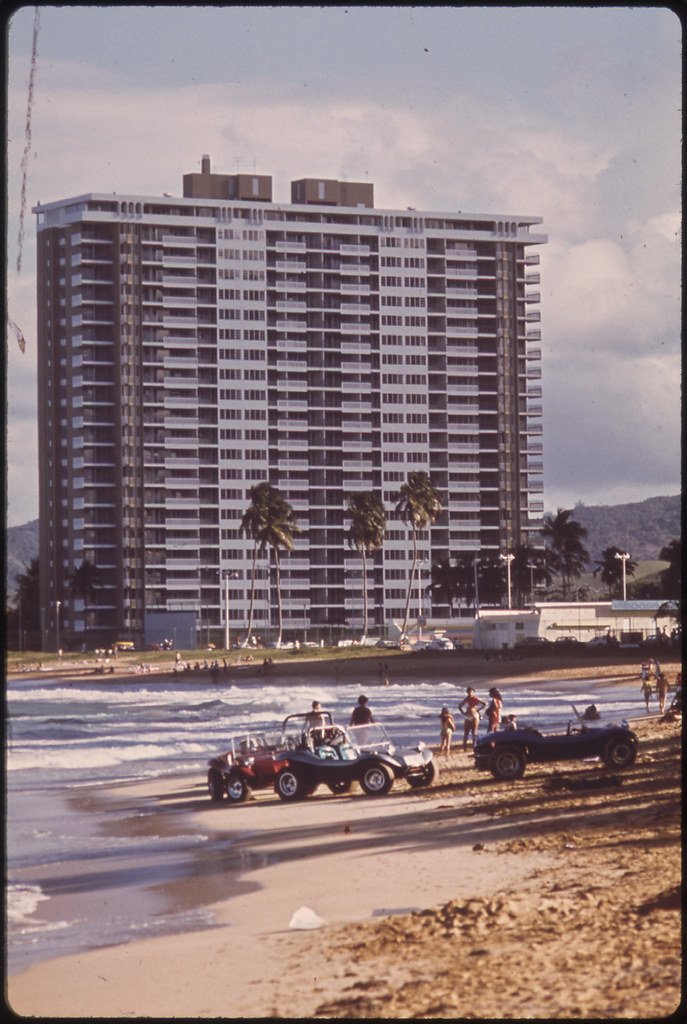

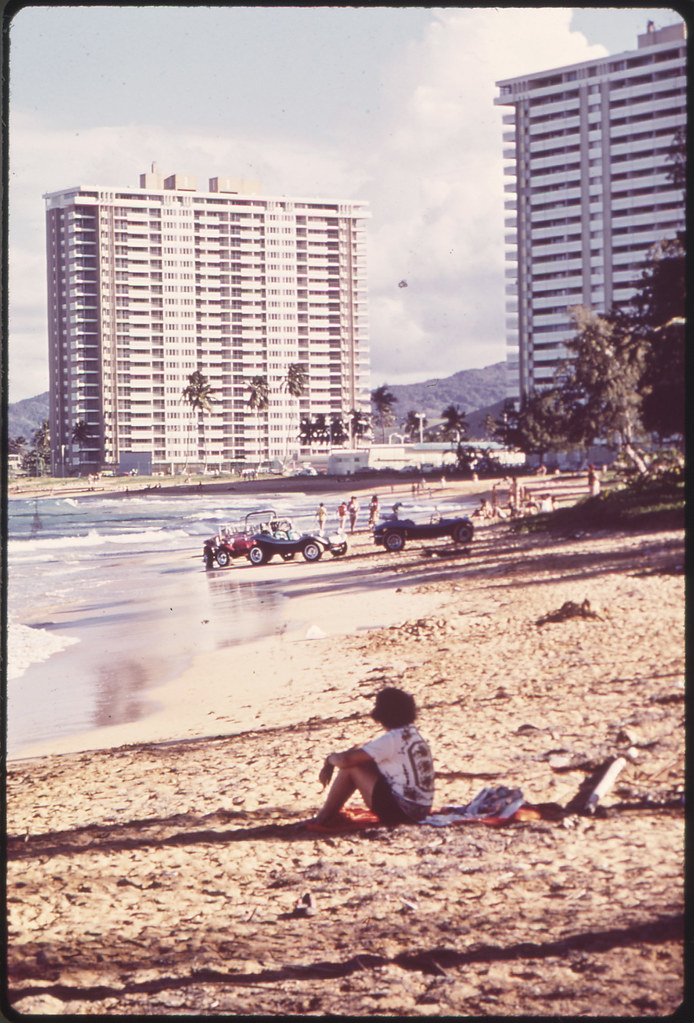

Luquillo Beach condominium, San Juan

On the coast

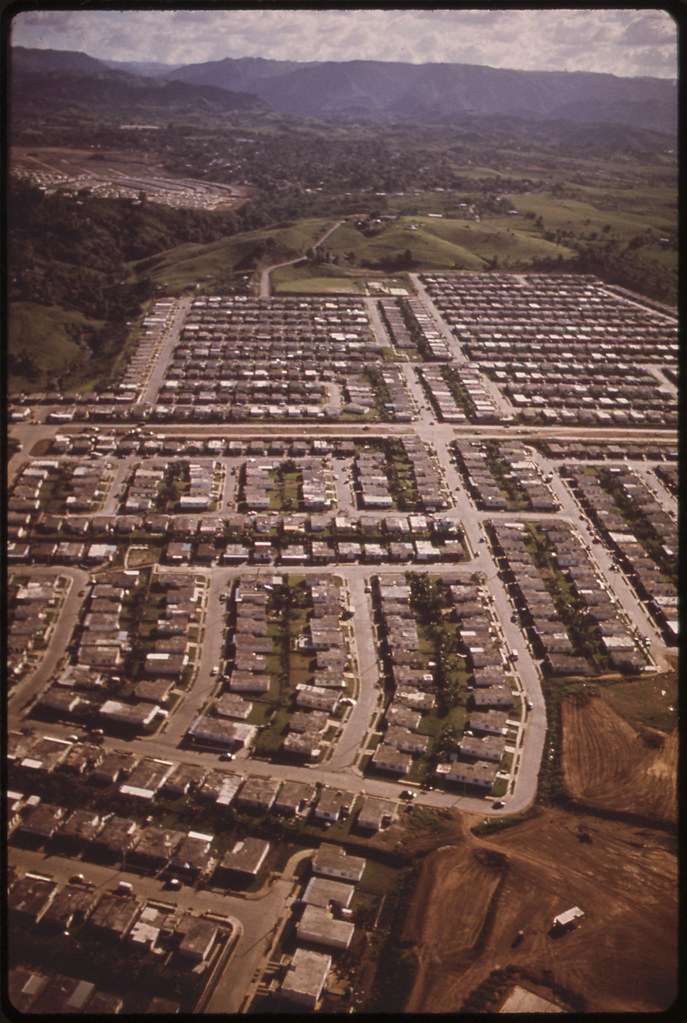

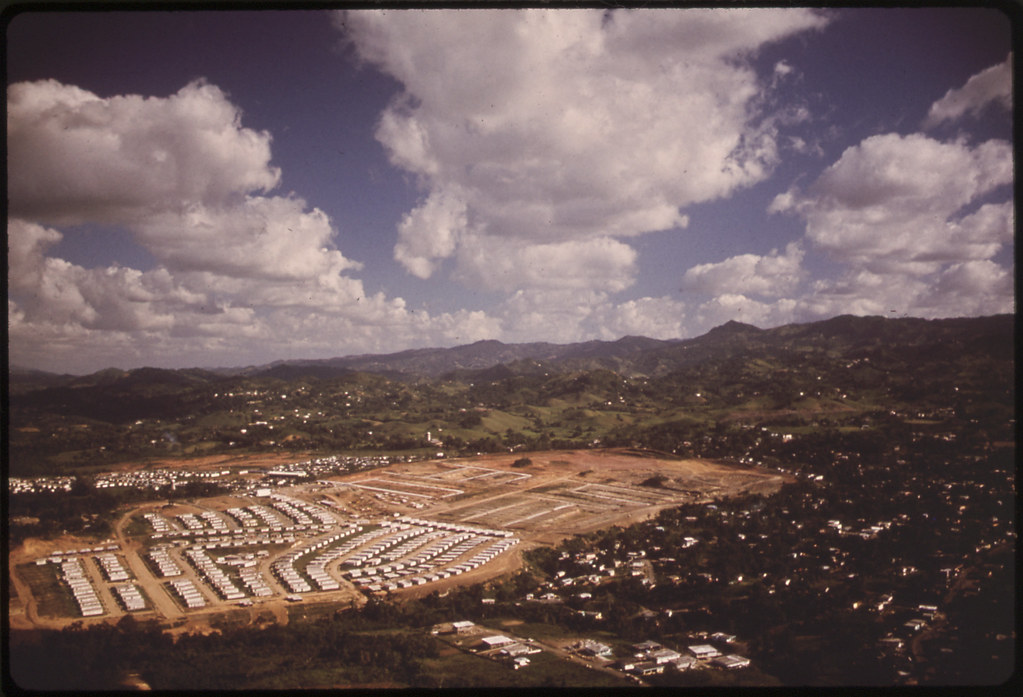

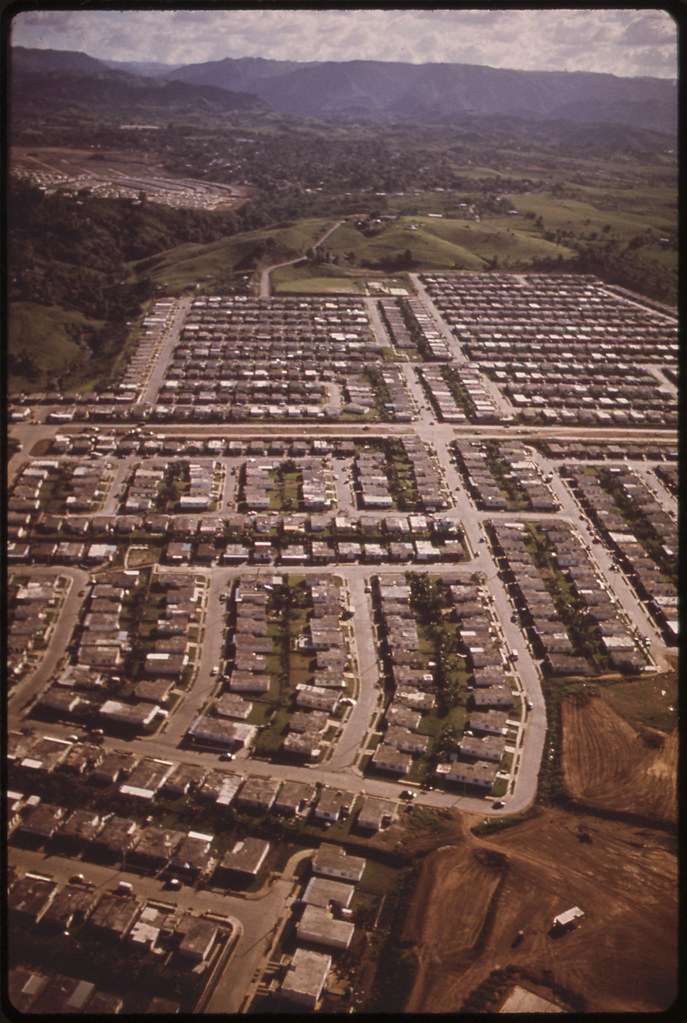

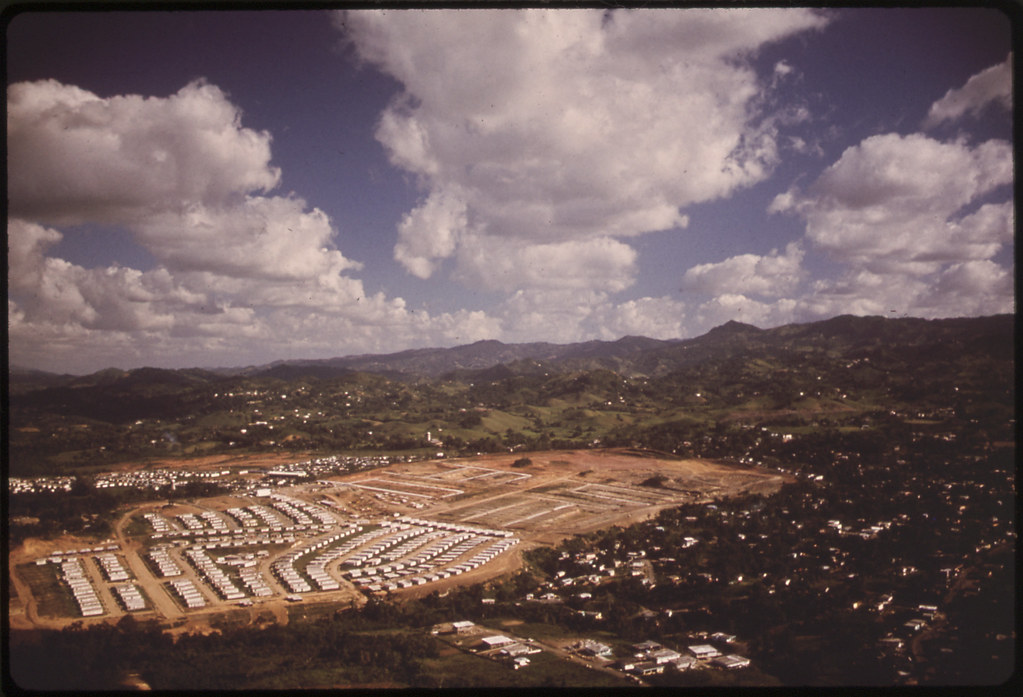

Bayamón housing development, San Juan

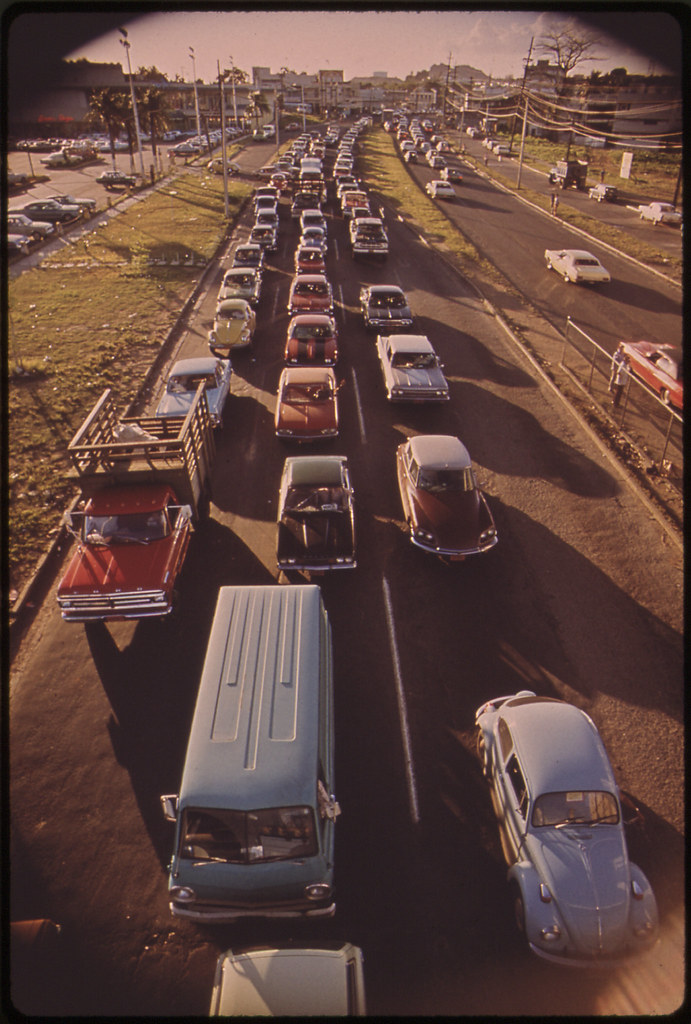

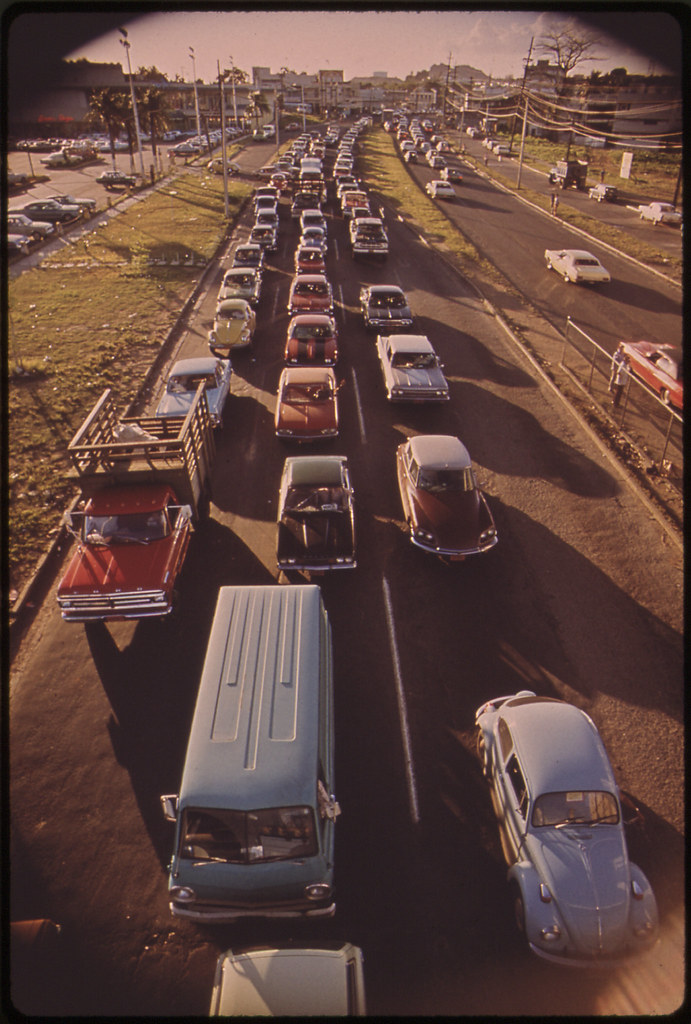

5 P.M. traffic on Route 2 in Bayamón

Bayamón housing development, San Juan

Atlantic Beach, Arecibo

Garbage-strewn Atlantic beach, Arecibo

Caribbean coastline, Santa Isabel, Guayama

Caribbean harbor outside Salinas, Guayama

Industrial area, San Juan

Industrial area, San Juan

Luquillo Beach, San Juan

Luquillo Beach, San Juan

Luquillo Beach, San Juan

Luquillo Beach, San Juan

Boat launching from Luquillo Beach, San Juan

Mayagüez-Aguadilla, Puerto Rico

Fishing from the dock at Playa de Playuela, Mayagüez

Burning garbage at an open dump on Highway 112 north of San Sebastian, Mayagüez

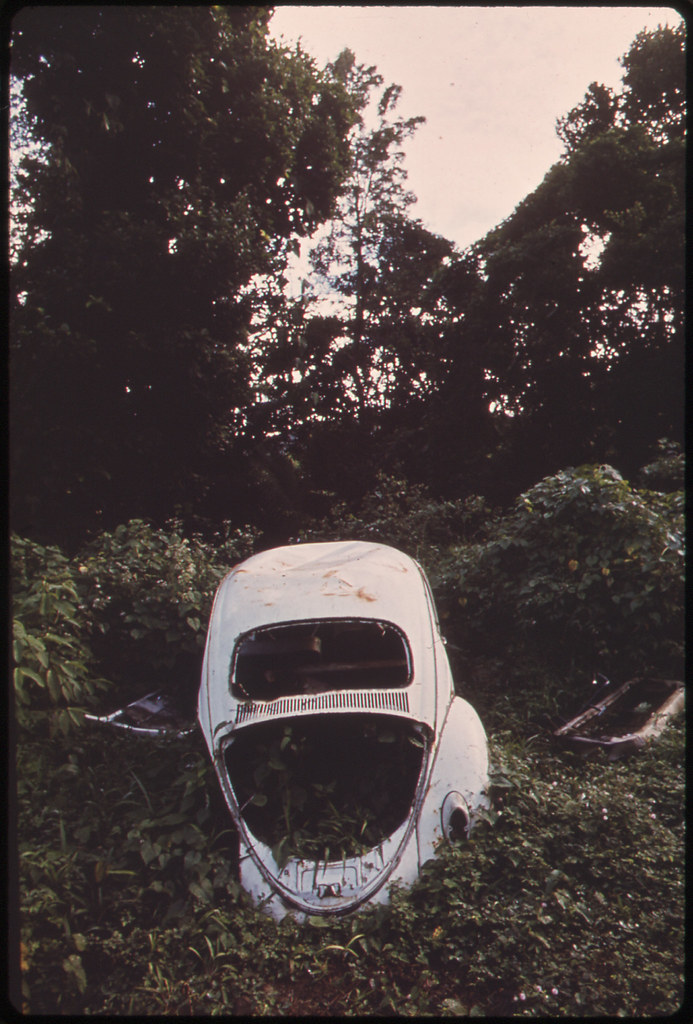

Burning garbage at an open dump on Highway 112 north of San Sebastian, Mayagüez

Burning garbage at an open dump on Highway 112

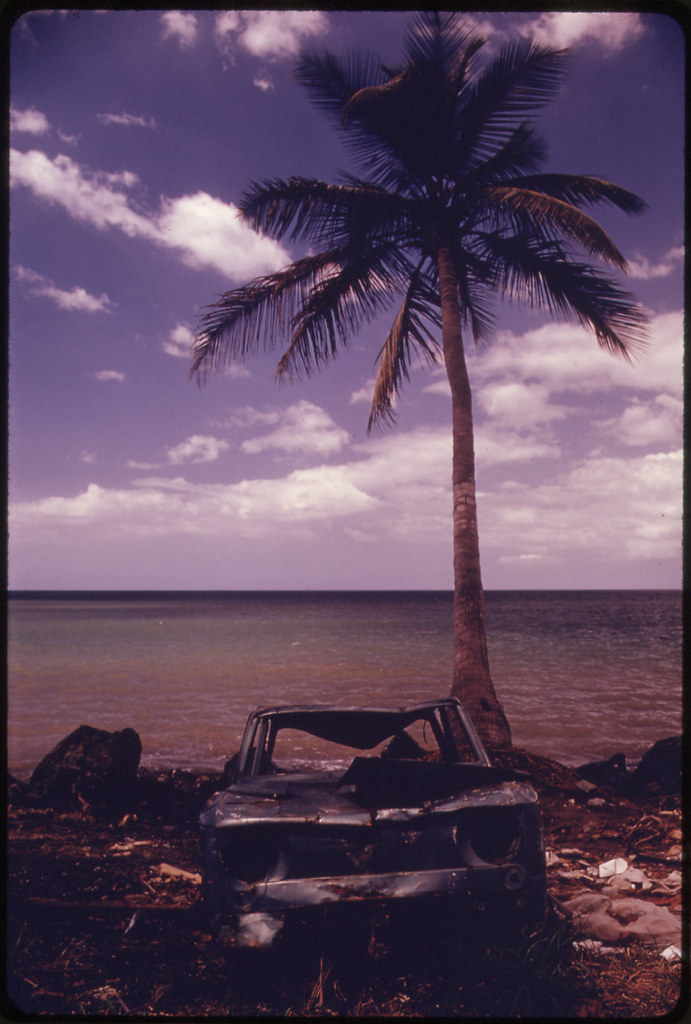

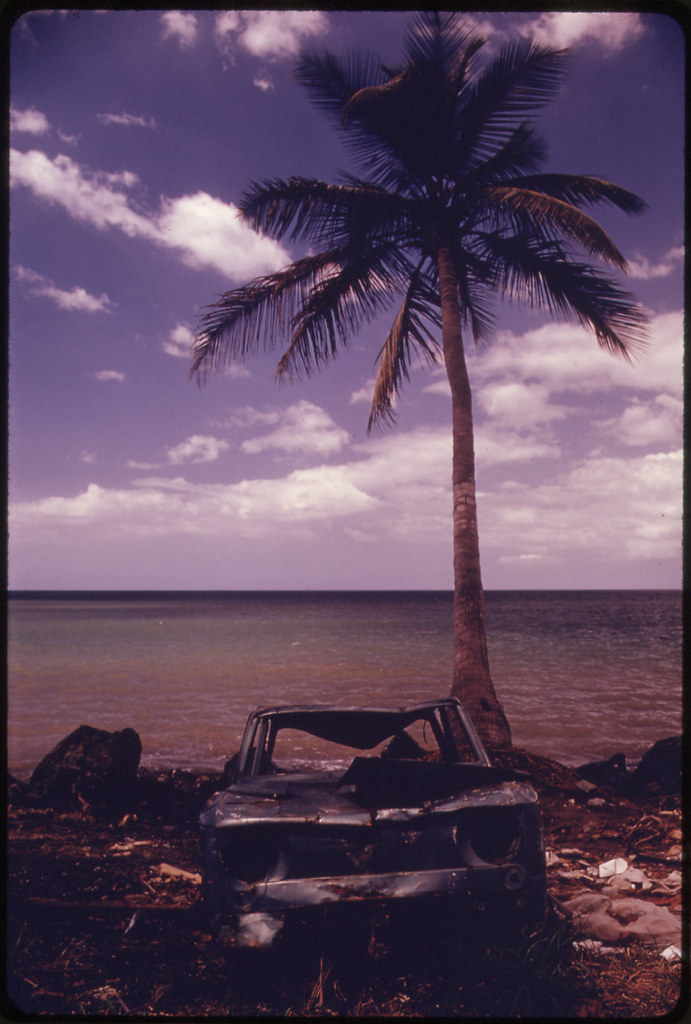

Abandoned car under a palm tree at Rincon, Mayagüez

Sugar cane and refinery near Mayagüez

Sugar refinery, Mayagüez

Sugar refinery. Trucks bring in freshly cut cane, Mayagüez

Sugar refinery and drainage ditch

Guaynabo River south of San Juan

Road near San Juan

A farmer clears his land with a machete

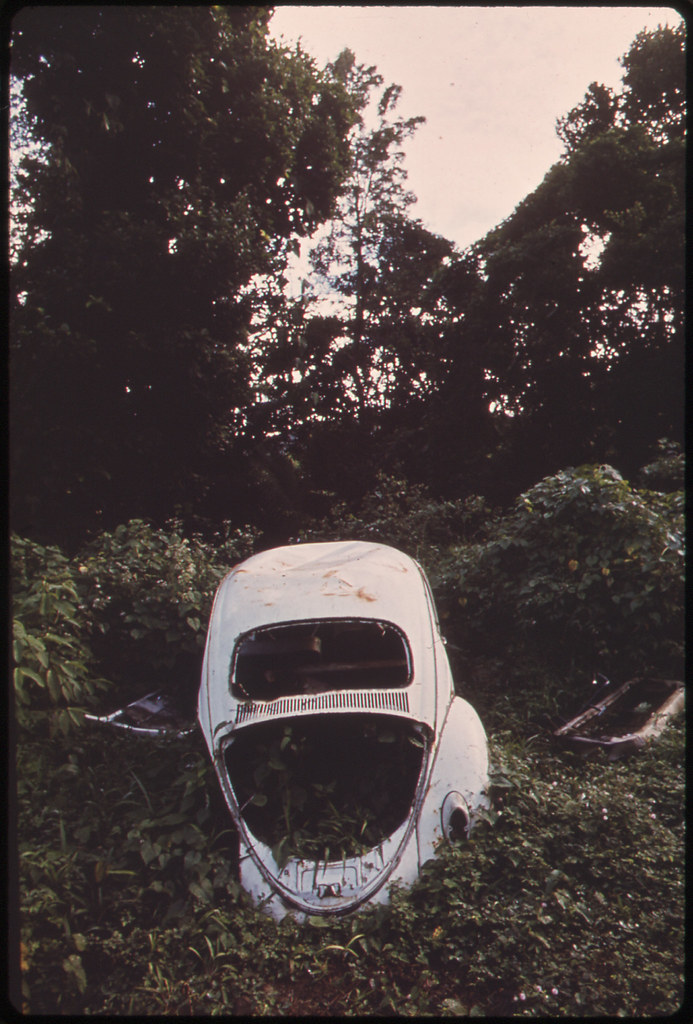

Abandoned car off highway in Rio Grande

Abandoned autos, near San Juan

New apartment buildings, San Juan

New apartment buildings, San Juan

High rise apartments on southern outskirt of the city, San Juan

Father and son fishing on Isla de Cabras, San Juan

Smoking chimneys of a cement plant in industrial area of San Juan

Palo Seco electric power plant across the bay from San Juan

Catano industrial area, across the bay from Old San Juan

Palo Seco electric power plant in the background, San Juan

Reservoir dam under construction, south of the city, San Juan

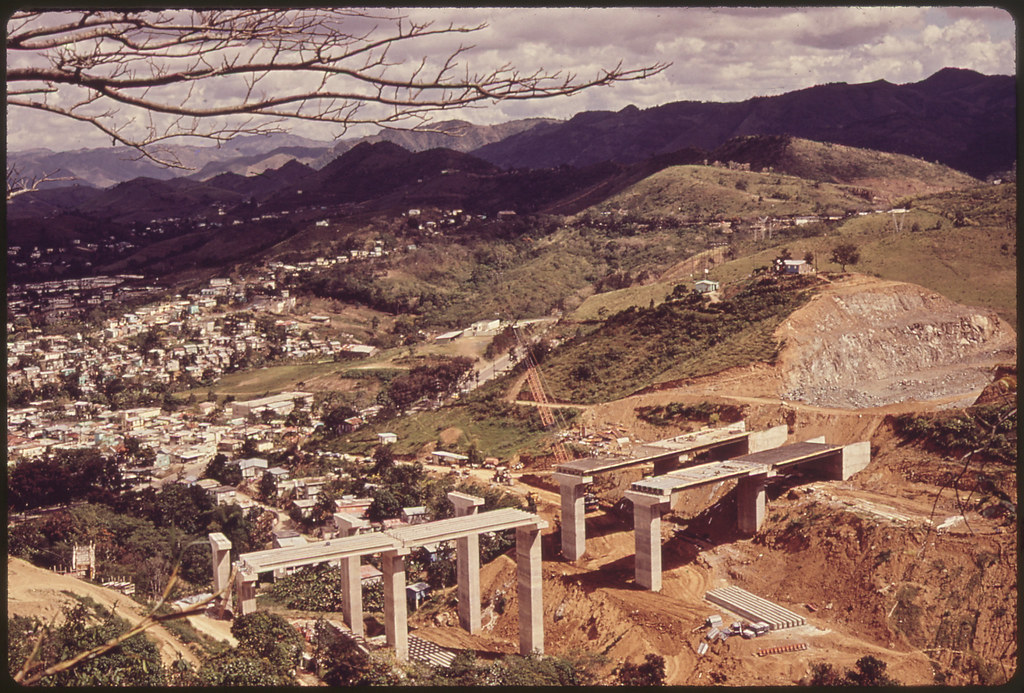

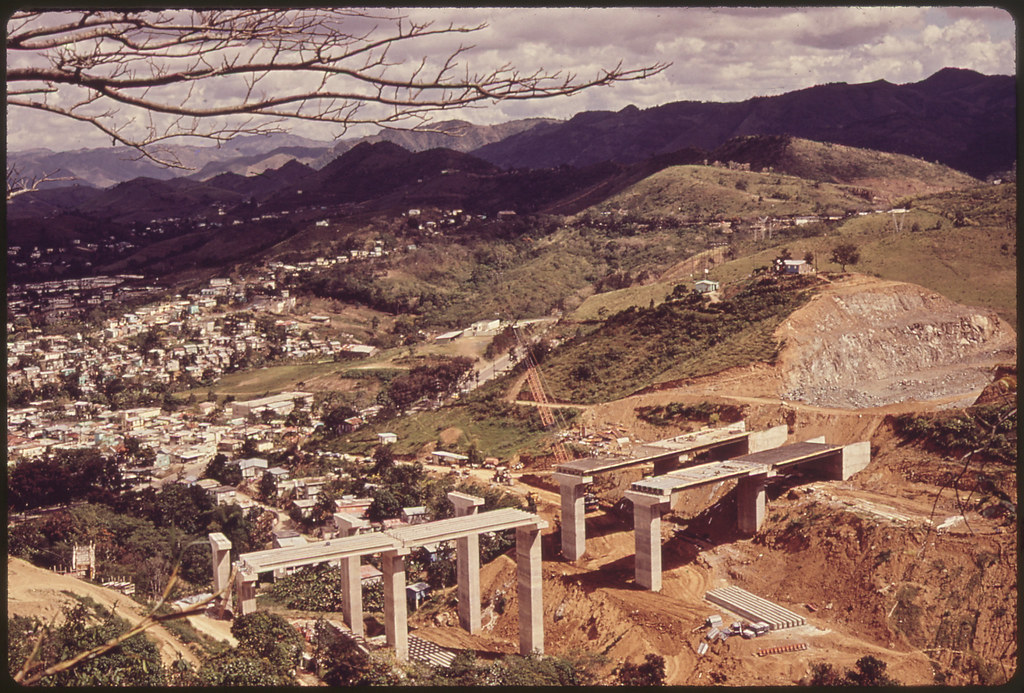

New toll road under construction between San Juan and Ponce; this section at Cayey

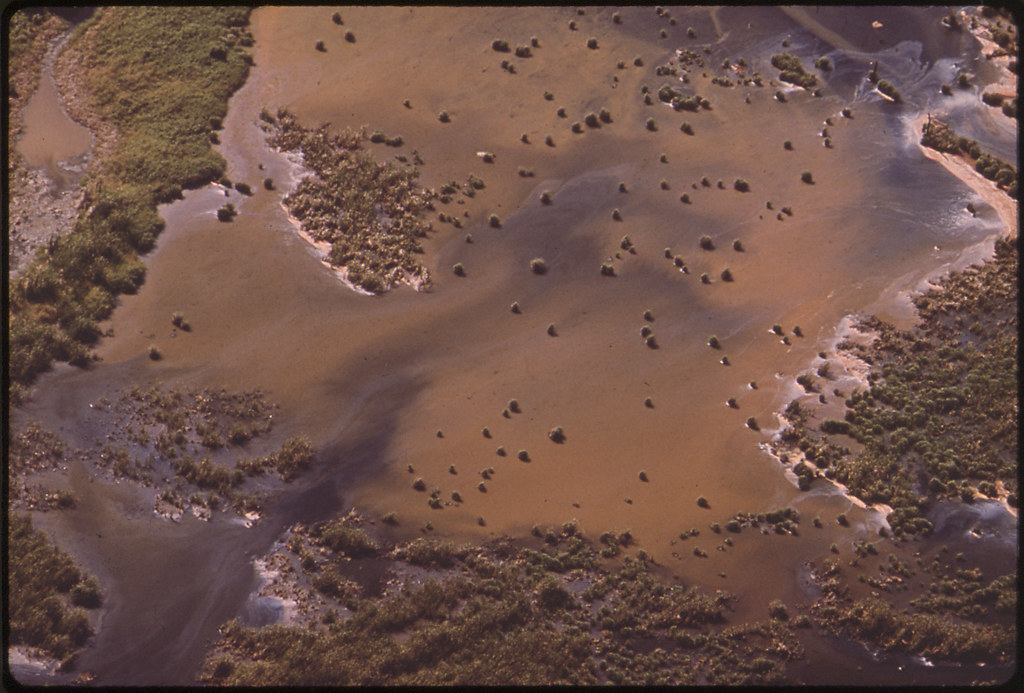

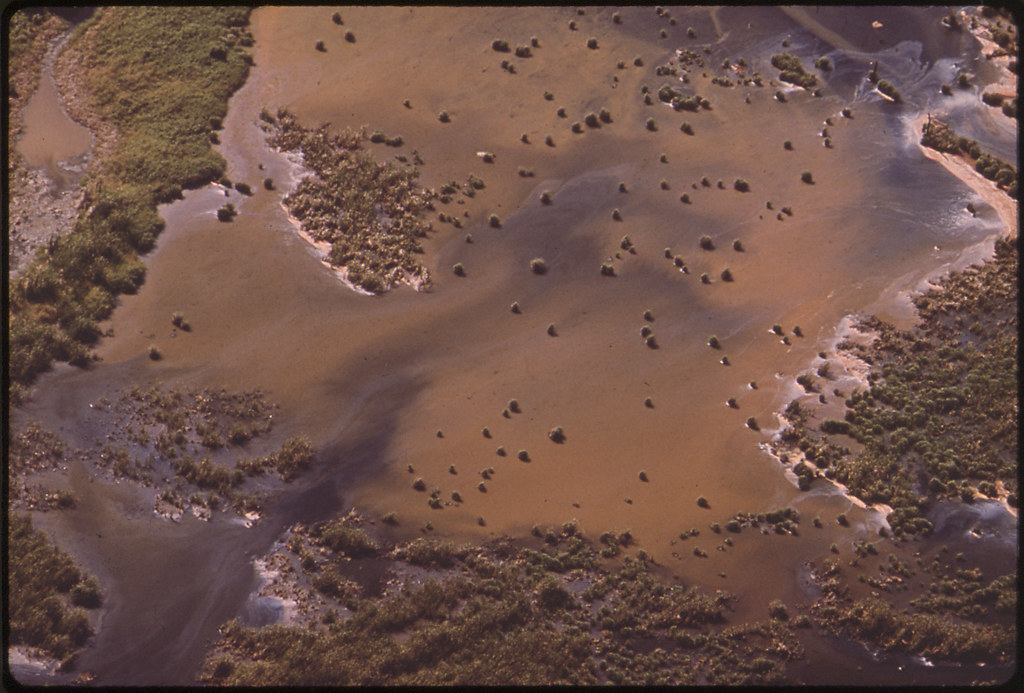

Aerial view of body of polluted water, Puerto Rico

Aerial view of body of polluted water, Puerto Rico

6:53 p.m. San Juan. “Once night falls, you won't see me outside,” said Ana Luz Pérez at her tidy apartment at the Luis Lloréns Torres housing project, the largest in Puerto Rico. It has 140 buildings and is plagued by crime.She ran through her options for light in the gloom of her apartment. She decided to conserve the two candles she had left and instead used the remaining gas in her green camping lantern. She turned the knob of the gaslight, and the light flickered, bringing the shadows in the kitchen to life. The rice with ham and sausage she had cooked for her boyfriend earlier in the day were growing cold on a small stove connected to a white gas tank on the floor. She turned on the stove to warm the meal. “It's the last tank left,” Ms. Pérez said. "We didn't know it was going to be so difficult." The blackout had given Ms. Pérez plenty of sleepless nights. She spends much of the time smoking cigarettes on her balcony or splashing her face with cool water. She’s up by 4 a.m. She thinks of her four children, ages 21 to 27, living in the Bronx. She worries about her mother, who is 60 and has cancer.“Solitude kills,” she said, breaking down in tears at her small glass dining table. Over the cacophony of barking dogs, her boyfriend, Carlos Rivera, climbed the stairs to her apartment. As his shadow grew bigger by her apartment door, Ms. Pérez did not attempt to hide her tears.: photo by Victor J. Blue for The New York Times, 30 September 2017

6:56 p.m. Arecibo. A long line formed to buy ice in Arecibo.: photo by Kirsten Luce for The New York Times, 30 September 2017

7:08 p.m. San Juan. Residents of the the Luis Lloréns Torres housing project watched a television hooked up to a car battery in San Juan on Wednesday.: photo by Victor J. Blue for The New York Times, 30 September 2017

2:30 a.m. Ponce. The Tropical Ice company does not open until 7 a.m., but already people were lined up outside. They brought lawn chairs, books and playing cards. Some brought blankets. They clearly aimed to spend the night, and plenty of them were already fast asleep. Roberto Gallego, 69, was first, an impressive feat in a row of people at least 100 deep. “11 o’clock at night!” he proudly exclaimed when asked what time one had to arrive at the ice factory to be first in line for two $1.50 bags of watery ice. Ice was not the only thing he was anticipating. Mr. Gallego was also anxious for the airports to reopen. “This changed my life,” he said. “I’m going to Orlando.”: photo by Erika P. Rodriguez for The New York Times, 30 September 2017

5:28 a.m. San Juan. There’s an expression in Puerto Rico: “Hay que echar pa’ lante.” It roughly translates to “Gotta move forward.” It is an expression of optimism in the face of adversity, which Puerto Rico had in abundance even before Maria. The storm threw Puerto Rico into the darkest, most hellish abyss it has seen in generations. Maybe it would be naïve to think that a sustained dose of “Hay que echar pa’ lante” is enough for the island and its people to make it through. But it would be a misunderstanding of Puerto Rico’s people and culture not to factor it in.: photo by Victor J. Blue for The New York Times, 30 September 2017

. Joey Ramos stays to protect his home from looters.: photo by Victor J. Blue for The New York Times, 30 September 2017

III John Vachon: Peligro (Puerto Rico, February 1973)

A village street, Ponce

Victor Hernández Cruz: Song 3

There was still no central heating

in the tenements

We thought that the cold was

the oldest thing on the planet earth

We used to think about my Uncle Listo

Who never left his hometown

We’d picture him sitting around

cooling himself with a fan

In that imaginary place

called Puerto Rico.

Victor Hernández Cruz (b. 1949, Aguas Buenas, Puerto Rico): Song 3

Mountain farm, Ponce

Mountain area, Ponce, Puerto Rico

A mountain farmhouse

Father and son fill their containers at the community water pump, mountain farming area, Ponce

Wild flowers, mountain area

There was still no central heating

in the tenements

We thought that the cold was

the oldest thing on the planet earth

We used to think about my Uncle Listo

Who never left his hometown

We’d picture him sitting around

cooling himself with a fan

In that imaginary place

called Puerto Rico.

Victor Hernández Cruz (b. 1949, Aguas Buenas, Puerto Rico): Song 3

Mountain farm, Ponce

Mountain area, Ponce, Puerto Rico

A mountain farmhouse

Father and son fill their containers at the community water pump, mountain farming area, Ponce

Wild flowers, mountain area

Sugar cane field and refinery, Ponce

Petrochemical plant in coastal area, Ponce

Oil refinery in the sunset, Ponce

Oil pipeline on the beach

Sign on bridge near PPG plant protesting air pollution, Ponce

Luquillo Beach condominium, San Juan

On the coast

Bayamón housing development, San Juan

5 P.M. traffic on Route 2 in Bayamón

Bayamón housing development, San Juan

Atlantic Beach, Arecibo

Garbage-strewn Atlantic beach, Arecibo

Caribbean coastline, Santa Isabel, Guayama

Caribbean harbor outside Salinas, Guayama

Industrial area, San Juan

Industrial area, San Juan

Luquillo Beach, San Juan

Luquillo Beach, San Juan

Luquillo Beach, San Juan

Luquillo Beach, San Juan

Boat launching from Luquillo Beach, San Juan

Mayagüez-Aguadilla, Puerto Rico

Fishing from the dock at Playa de Playuela, Mayagüez

Burning garbage at an open dump on Highway 112 north of San Sebastian, Mayagüez

Burning garbage at an open dump on Highway 112 north of San Sebastian, Mayagüez

Burning garbage at an open dump on Highway 112

Abandoned car under a palm tree at Rincon, Mayagüez

Sugar cane and refinery near Mayagüez

Sugar refinery, Mayagüez

Sugar refinery. Trucks bring in freshly cut cane, Mayagüez

Sugar refinery and drainage ditch

Guaynabo River south of San Juan

Road near San Juan

A farmer clears his land with a machete

Abandoned car off highway in Rio Grande

Abandoned autos, near San Juan

New apartment buildings, San Juan

New apartment buildings, San Juan

High rise apartments on southern outskirt of the city, San Juan

Father and son fishing on Isla de Cabras, San Juan

Smoking chimneys of a cement plant in industrial area of San Juan

Palo Seco electric power plant across the bay from San Juan

Catano industrial area, across the bay from Old San Juan

Palo Seco electric power plant in the background, San Juan

Reservoir dam under construction, south of the city, San Juan

New toll road under construction between San Juan and Ponce; this section at Cayey

Aerial view of body of polluted water, Puerto Rico

All photos by John Vachon (1914-1975), February 1973, from the series DOCUMERICA: The Environmental Protection Agency's Program to Photographically Document Subjects of Environmental Concern (1972-1977) (Still Picture Records Section, Special Media Media Archives Services

Division, US National Archives at College Park, Maryland)

Iggy Pop: Lust for Life + Pumping for Jill (live, Cabaret Tour, Encore, SF 1981)

ReplyDeleteHey Tom. We've travelled to Chicago, Baltimore & Pittsburgh in recent weeks. Enjoyed the pictures of those places, esp. Pittsburgh -- Dive Bar, the opposing steps & Mexican War Streets on the North Side. Your daily work here on the relentless cruelty on the Rohingya people is heartbreaking. You've been watching that emerge for years. Now there is evidently a film on the breadth of Wirathu's evil. Maybe it will help but maybe not as it does appear the earth is indeed in the hands of the wrong people. John Vachon's pictures are a dream turned into our nightmare, no? Another paradise lost, as per Borges? Finally, had to laugh at the Marquis de Favras' last words. I can say for sure I didn't write the edict, Boss.

ReplyDeleteThanks, Tom. Sounds like an interesting trip. If you were tempted to suspect the Pittsburgh photos I've posted of late were meant for you... you'd be right.

ReplyDeleteYes, Vachon, another lost paradise, as he found it (pave paradise and put up a parking lot). A beautiful dispassionate survey of the protracted expropriation of the island as playground/factory, by the same bad big-brother neighbors we were then and still are now.