Red Pike and Crummock Water nr Buttermere #lakedistrict. Love visiting this area, so many walks @WalksAndWalking: image via lynda hill @Windermere99, 10 March 2015

Signs I'm getting older..nature pics! Here's a wide shot of the #HonisterPass in the beautiful #LakeDistrict #Cumbria: image via Tim Holt @timholt, 4 March 2017

Sonntagsspaziergang im Schnee | Marchweg Wil [Switzerland]: photo by rdie, 10 December 2017

Sonntagsspaziergang im Schnee | Marchweg Wil [Switzerland]: photo by rdie, 10 December 2017

Sonntagsspaziergang im Schnee | Marchweg Wil [Switzerland]: photo by rdie, 10 December 2017

Harrowed Field with Windmill, Eastern Washington: photo by Austin Granger, 11 December 2017

Ward Hill #3 (Andover, Massachusetts): photo by Jim Rohan (LowerDarnley), 14 January 2014

They hail me as one living,

But don't they know

That I have died of late years,

Untombed although?

But don't they know

That I have died of late years,

Untombed although?

I am but a shape that stands here,

A pulseless mould,

A pale past picture, screening

Ashes gone cold.

A pulseless mould,

A pale past picture, screening

Ashes gone cold.

Not at a minute's warning,

Not in a loud hour,

For me ceased Time's enchantments

In hall and bower.

There was no tragic transit,

No catch of breath,

When silent seasons inched me

On to this death ....

-- A Troubadour-youth I rambled

With Life for lyre,

The beats of being raging

In me like fire.

But when I practised eyeing

The goal of men,

It iced me, and I perished

A little then.

When passed my friend, my kinsfolk,

Through the Last Door,

And left me standing bleakly,

I died yet more;

And when my Love's heart kindled

In hate of me,

Wherefore I knew not, died I

One more degree.

And if when I died fully

I cannot say,

And changed into the corpse-thing

I am to-day,

Yet is it that, though whiling

The time somehow

In walking, talking, smiling,

I live not now.

Thomas Hardy (1840-1928): The Dead Man Walking, from Time's Laughingstocks and Other Verses, 1909

Tree with Broken Windmill, Eastern Washington: photo by Austin Granger, 12 December 2017

Tree with Broken Windmill, Eastern Washington: photo by Austin Granger, 12 December 2017

Tree with Broken Windmill, Eastern Washington: photo by Austin Granger, 12 December 2017

Tree with Broken Windmill, Eastern Washington: photo by Austin Granger, 12 December 2017

Tree with Broken Windmill, Eastern Washington: photo by Austin Granger, 12 December 2017

Ward Hill #2 (Andover, Massachusetts): photo by Jim Rohan (LowerDarnley), 13 January 2014

Nelson Island #1 (Rowley, Massachusetts): photo by Jim Rohan (LowerDarnley), 12 January 2014

Trees in Fog, Washington: photo by Austin Granger, 7 December 2017

Trees in Fog, Washington: photo by Austin Granger, 7 December 2017

Trees in Fog, Washington: photo by Austin Granger, 7 December 2017

Sonntagsspaziergang im Schnee | Marchweg Wil [Switzerland]: photo by rdie, 10 December 2017

Sonntagsspaziergang im Schnee | Marchweg Wil [Switzerland]: photo by rdie, 10 December 2017

Sonntagsspaziergang im Schnee | Marchweg Wil [Switzerland]: photo by rdie, 10 December 2017

Windmill, Eastern Oregon: photo by Austin Granger, 10 December 2017

Windmill, Eastern Oregon: photo by Austin Granger, 10 December 2017

Windmill, Eastern Oregon: photo by Austin Granger, 10 December 2017

Krienseregg im Nebel Pilatus Luzern Switzerland: photo by rdie, 6 December 2017

Krienseregg im Nebel Pilatus Luzern Switzerland: photo by rdie, 6 December 2017

Krienseregg im Nebel Pilatus Luzern Switzerland: photo by rdie, 6 December 2017

Adams Pasture in Winter #9 (Newbury, Massachusetts): photo by Jim Rohan (LowerDarnley), 14 January 2014

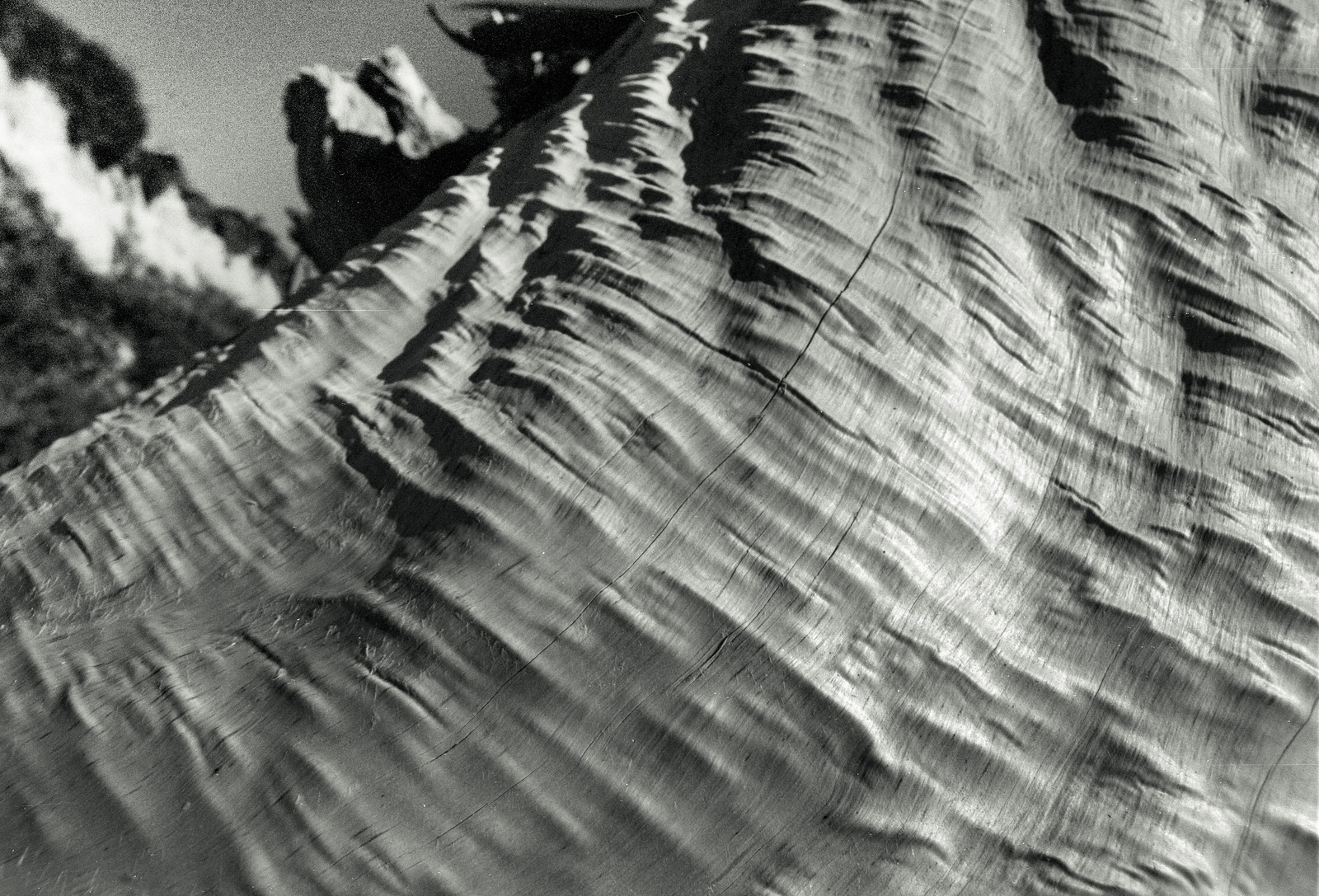

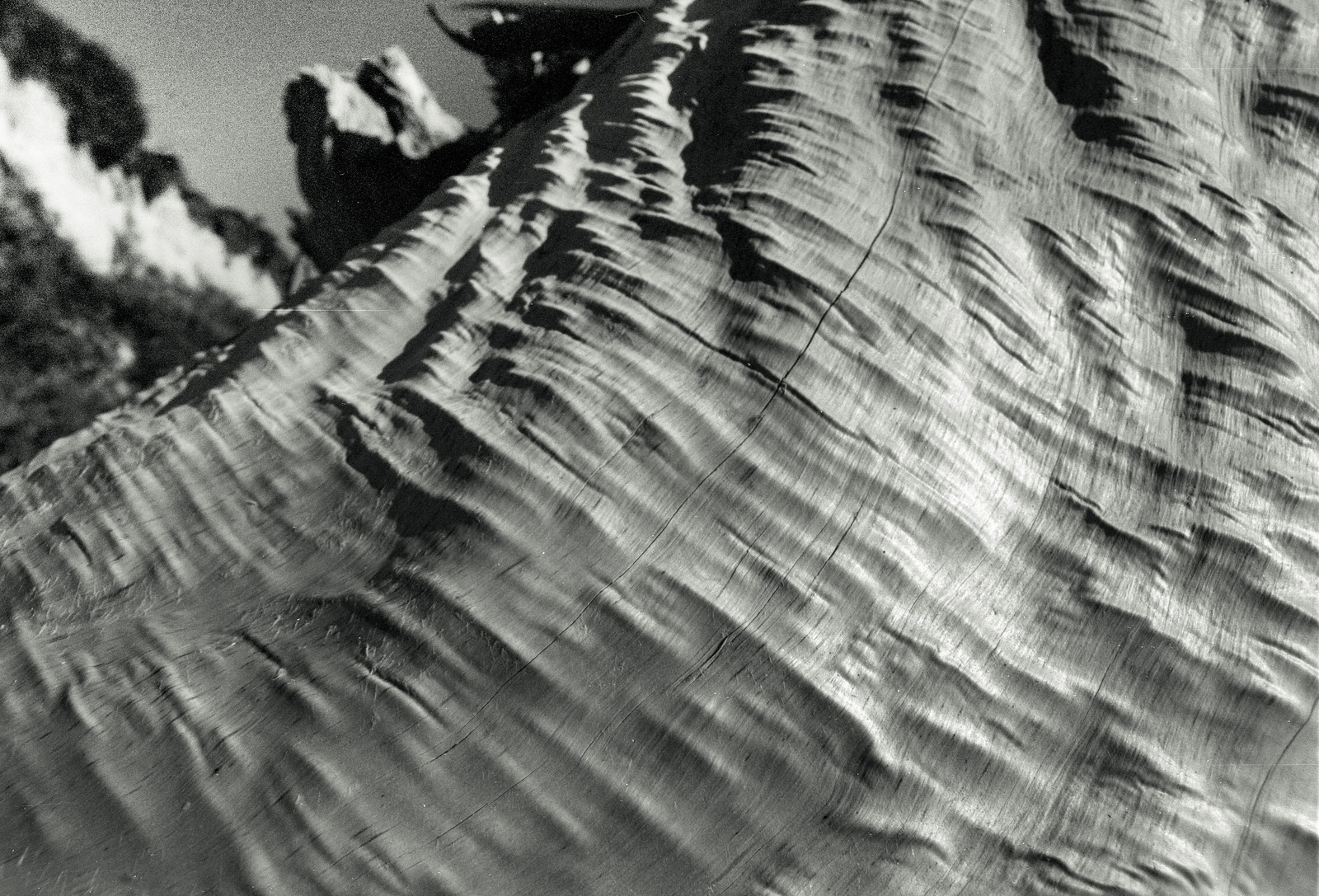

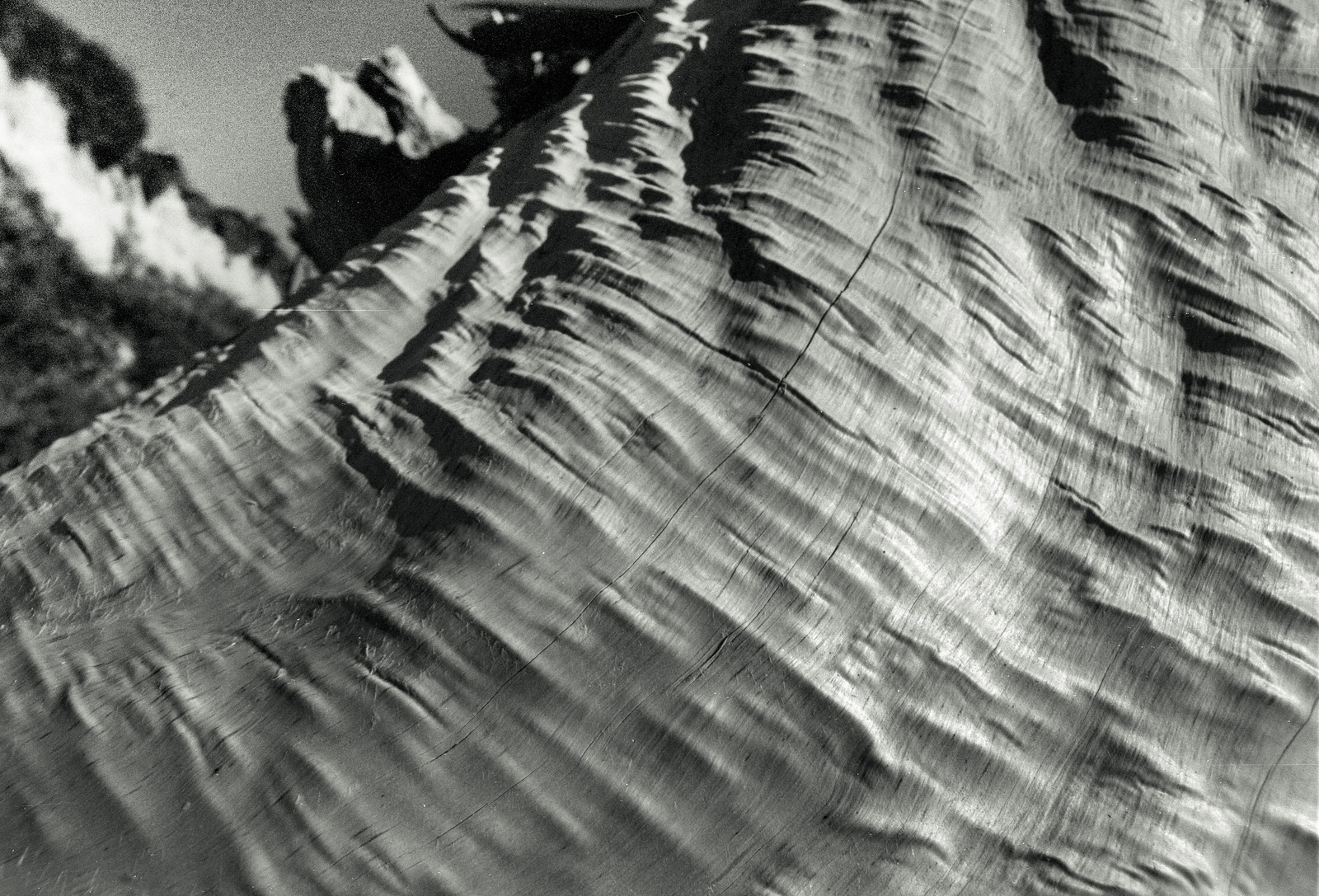

Spotmatic Drift 2: photo by Nick Lyle, 9 December 2017

Spotmatic Drift 2: photo by Nick Lyle, 9 December 2017

Spotmatic Drift 2: photo by Nick Lyle, 9 December 2017

5273 [gypsies]: photo by Petros Kotzabasis, 5 January 2010

5273 [gypsies]: photo by Petros Kotzabasis, 5 January 2010

Wallace Stevens: The Snow Man

Cat dancing in snow (Yippieeee! Let's dance!): photo by Matthias Zirngibl, 2006

One must have a mind of winter

To regard the frost and the boughs

Of the pine-trees crusted with snow;

To regard the frost and the boughs

Of the pine-trees crusted with snow;

And have been cold a long time

To behold the junipers shagged with ice,

The spruces rough in the distant glitter

To behold the junipers shagged with ice,

The spruces rough in the distant glitter

Of the January sun; and not to think

Of any misery in the sound of the wind,

In the sound of a few leaves,

Of any misery in the sound of the wind,

In the sound of a few leaves,

Which is the sound of the land

Full of the same wind

That is blowing in the same bare place

Full of the same wind

That is blowing in the same bare place

For the listener, who listens in the snow,

And, nothing himself, beholds

Nothing that is not there and the nothing that is.

And, nothing himself, beholds

Nothing that is not there and the nothing that is.

Wallace Stevens (1870-1955): The Snow Man, 1921, from Harmonium (1923)

black cat, white snow: photo by wikkanman, 26 January 2013

black cat, white snow: photo by wikkanman, 26 January 2013

Thomas Hardy: Snow in the Suburbs

White-throated Sparrow (Zonotrichia albicollis) in snow storm: photo by Steve Byland, 14 December 2013

........Every branch big with it,

........Bent every twig with it;

......Every fork like a white web-foot;

......Every street and pavement mute:

Some flakes have lost their way, and grope back upward, when

Meeting those meandering down they turn and descend again.

....The palings are glued together like a wall,

....And there is no waft of wind with the fleecy fall.

........

........A sparrow enters the tree,

........Whereon immediately

......A snow-lump thrice his own slight size

......Descends on him and showers his head and eyes,

..........And overturns him,

..........And near inurns him,

........And lights on a nether twig, when its brush

Starts off a volley of other lodging lumps with a rush.

........

........The steps are a blanched slope,

........Up which, with feeble hope,

........A black cat comes, wide-eyed and thin;

..........And we take him in.

Thomas Hardy (1840-1928): Snow in the Suburbs, from Human Shows, Far Phantasies, Songs and Trifles, 1925

Song Sparrow in snow, Lost Lagoon, Vancouver, British Columbia: photo by Valerie Sauve, 20 December 2013

Winter Weirder Land: photo by David Cory, 8 January 2011

Winter Weirder Land: photo by David Cory, 8 January 2011

Winter Weirder Land: photo by David Cory, 8 January 2011

Winter Weirder Land: photo by David Cory, 8 January 2011

Winter Weirder Land: photo by David Cory, 8 January 2011

Winter Weirder Land: photo by David Cory, 8 January 2011

Tree and snow: photo by David Cory, 2 January 2010

Winter Weirder Land: photo by David Cory, 8 January 2011

White-throated Sparrow in snow: photo by The Nature Nook, 9 March 2009

William Wordsworth: Two Lyrical Ballads

[Untitled]: photo by Danielle Houghton, 21 April 2017

William Wordsworth: "A slumber did my spirit seal"

Amur tiger (Panthera tigris altaica) with cub: photo by Dave Pape, 2008

A slumber did my spirit seal,

I had no human fears:

She seemed a thing that could not feel

The touch of earthly years.

No motion has she now, no force

She neither hears nor sees

Rolled round in earth's diurnal course

With rocks and stones and trees!

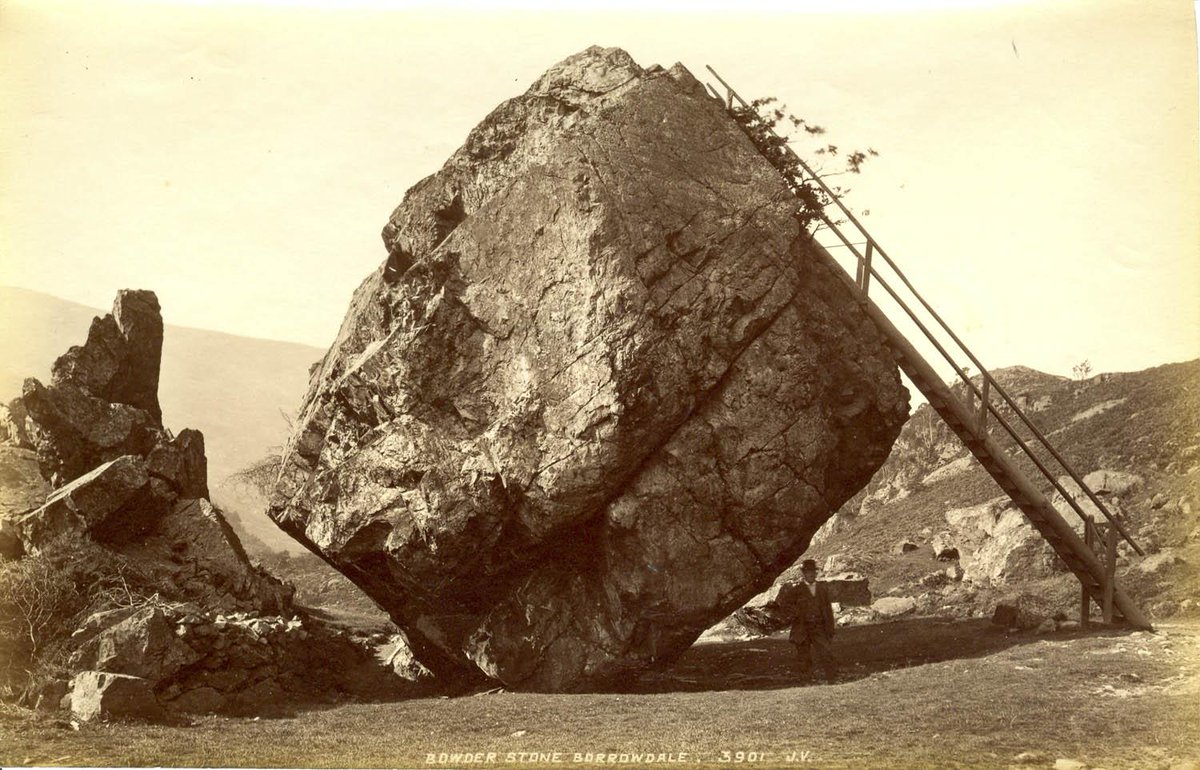

Late Victorian photograph of the iconic Bowder Stone in #Borrowdale #LakeDistrict @theldwalker @townsendoutdoor: image via The Ice Age @JamieWoodward_, 3 March 2015

William Wordsworth (1770-1850): "A slumber did my spirit seal", 1799, from Lyrical Ballads, 1800

William Wordsworth: "She dwelt among th'untrodden ways"

Semi-wild fell ponies, West Fell, 3km from Nether Row, Cumbria: photo by Chris Eilbeck, 4 November 2007

She dwelt among th' untrodden ways

Beside the springs of Dove,

A maid whom there were none to praise

And very few to love.

Beside the springs of Dove,

A maid whom there were none to praise

And very few to love.

Semi-wild fell ponies: photo by Roy Wall, 8 May 2005

A Violet by a mossy stone

Half-hidden from the eye!

-- Fair, as a star when only one

Is shining in the sky!

Half-hidden from the eye!

-- Fair, as a star when only one

Is shining in the sky!

A herd of ponies near Roundhouse near to Mosedale, Cumbria: photo by Helen Wilkinson, 13 November 2007

She lived unknown, and few could know

When Lucy ceased to be;

But she is in her Grave, and, Oh!

The difference to me!

But she is in her Grave, and, Oh!

The difference to me!

Ford and ponies, Hay Gill: photo by Bob Jenkins, 21 December 2005

Fell ponies roaming free over the commons near Mungrisdale and Caldbeck: photo by Ann Hodgson, 13 August 2003

William Wordsworth (1770-1850): "She dwelt among th' untrodden ways", 1799, from Lyrical Ballads, 1800

#Iraq A girl stands on a hill close to her home in eastern #Mosul. By @markodjurica @reuterspictures: image via Marko Djurica @markodjurica, 19 April 2017

#instantané Une fillette syrienne dans un camp situé à la frontière

turco-syrienne, dimanche Photo @Delilsouleman #AFP: image via Agence

France-Presse @afpfr, 24 April 2017

#Iraq An Iraqi woman carries a child in a street in the western part of

Iraq's northern city of Mosul during #MosulOffensive Photo @tofsimon: image via Frédérique Geffard @fgeffardAFP, 24 April 2017

#Italy A child sits on the deck of the Malta-based NGO @moas_eu ship Phoenix as it arrives in Augusta. By @darrinzi @reuterspictures: image via Photojournalism @photojournalink, 25 April 2017

#India A child lies in a hammock made from salvaged material at a garbage dump on the outskirts of Chennai. @ArunsankarKrish: image @Frédérique Geffard @fgeffardAFP, 25 April 2017

#Italy A child sits on the deck of the Malta-based NGO @moas_eu ship Phoenix as it arrives in Augusta. By @darrinzi @reuterspictures: image via Photojournalism @photojournalink, 25 April 2017

#India A child lies in a hammock made from salvaged material at a garbage dump on the outskirts of Chennai. @ArunsankarKrish: image @Frédérique Geffard @fgeffardAFP, 25 April 2017

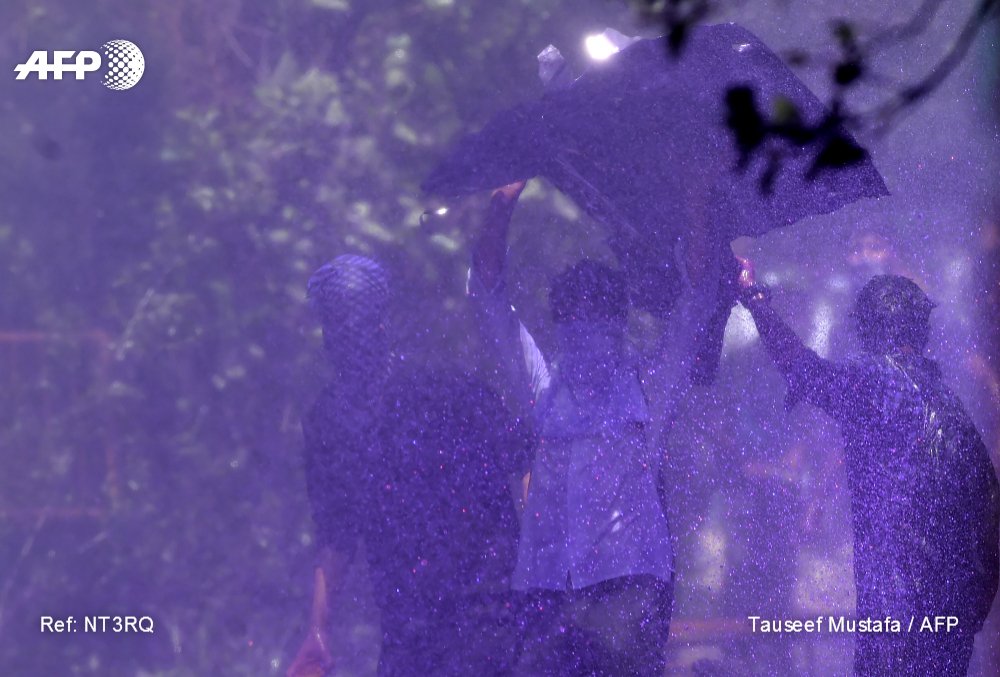

Muslims pray during celebrations for Miraj-Ul-Alam (ascension to heaven) at Kashmir's main Hazratbal Shrine in Srinagar. Photo @TauseefMUSTAFA: image via Frédérique Geffard @fgeffardAFP, 25 April 2017

Kashmiri Muslim devotees pray as a head priest displays a holy relic believed to be the hair from the beard of Prophet Mohammad, on Mehraj-u-Alam at the Hazratbal Shrine on the outskirts of Srinagar. Mehraj-u-Alam is believed to mark the ascension of Prophet Mohammad to heaven.: photo by Mukhtar Khan/AP, 25 April 2017

Kashmiri students gesture towards Indian government forces who fired a coloured water cannon in Srinagar's Lal Chowk. Photo @TauseefMUSTAFA: image via Frédérique Geffard @fgeffardAFP, 24 April 2017

Virginia Woolf: Wordsworth's Guide to the Lakes (1906)

1875 pic:: Picturesque #Grasmere Village, the burial place of English poet William #Wordsworth: image via villagehistorypics @villagehistory, 24 October 2015

WORDSWORTH’S GUIDE TO THE LAKES

With an Introduction, Appendices, and Notes, textual and illustrative, by ERNEST DE SÉLINCOURT (Frowde. 2s. 6d. net.)

MONTHS AT THE LAKES

By the Rev. H. D. RAWNSLEY (MacLehose. 5s. net.)

Wordsworth wrote his Guide to the Lakes in 1810, to preface a work by the Rev Joseph Wilkinson, who had drawn a folio volume of select views. But the drawings were, as Wordsworth was the first to pronounce, so “intolerable” that he had his preface severed from the main volume and published separately. In spite of its popularity in this shape, however –- some one asked him whether he had written anything else –- the book has not been reprinted as a separate volume since 1864; and many readers will have reason to thank Mr de Sélincourt for his letter of introduction to a new and happily permanent friend. In his excellent preface, which, besides furnishing all facts, suggests the right way of approaching them, Mr de Sélincourt tells us something of the sentimental history of the Lakes. In 1810 they were already the subject of curiosity, although they had not been domesticated in the sense that they are to-day. The people who went went in the conscious spirit of explorers, to bring back tales of what they had seen and to figure hereafter as travellers, rather than as private people who might keep their emotions to themselves. It was the custom to preserve these experiences in prose or verse; but these volumes do not, as Mr de Sélincourt says, “afford invigorating reading.” There was, perhaps, some affectation in their appreciation, and a tendency to approach lakes and mountains with a mind on the defensive against any attacks upon its sensibility. Mountains are “horrid”, and when praise is given, the curiously obsolete and artificial sound of it suggests that it is inspired by a wish to save the writer’s reputation as a man of taste rather than by a simple desire to write the truth.

Wordsworth, coming after these somewhat perplexed and perfunctory tourists, wrote with the calm authority of one who had lived for all but three years of his life among the scenes he describes. He has all the courtesy and consideration of an old inhabitant who does the honours of the place to a stranger, and who not only undertakes to show him the beauties, but will explain from his abundant and well-ordered knowledge any fact of history or geography that seems to him worth observation. He is jealous for his country’s credit, but his familiarity with the place is so perfect that no view will drive him into hasty exaggeration; he admires what he has seen and tested during a life time and knows to deserve and require every word he bestows. At first, it is true, the reader may detect some old-fashioned formality in his guide; he uses still the somewhat rigid vocabulary that was then thought proper for natural things; he will talk of a view that is “rich in a diversity of pleasing or grand scenery”, of “prospects” and “situations”, and he condescends more than a poet should to direct you how best to secure beds at the inn, “as there is but one, and it is much resorted to in summer.” But this very sedateness has its value, and seems to prove that the beauty is real enough to suffer examination by a perfectly candid and conscientious temper. These sober details, moreover, give a tone of solidity to the whole, and suggest the rough surface of the earth, which is as true a part of the country as its heights and its splendours.

Let us station ourselves in a cloud, he begins, hanging midway between Great Gavel or Scawfell; “we shall then see stretched at our feet a number of valleys, not fewer than eight . . . diverging from the point . . . like spokes from the nave of a wheel.” After this general survey he goes on to follow out certain paths in detail, making general observations on the form of the country and gradually narrowing his gaze till he gives us those closely-observed trifles which only a very penetrating eye after long search could have selected and described.

He knows not only the scientific reasons why the rocky part of a mountain is blue or “hoary grey”, with a tinge of red in it “like the compound hues of a dove’s neck”, but also which shade of green is due to the lichen and which to the fern that grows when the first grass is faded. But all through this minute and scrupulous catalogue there runs a purpose which solves it into one coherent and increasingly impressive picture. For all these details and more “which a volume would not be sufficient to describe” are of such interest to him because he sees them all as living parts of a vast and exquisitely ordered system. It is this combination in him of obstinate truth and fervent imagination that stamps his descriptions more deeply upon the mind than those of almost any other writer. “Days of unsettled weather,” he says, “with partial showers, are very frequent, but the showers, darkening or brightening as they fly from hill to hill, are not less grateful to the eye than finely interwoven passages of gay and sad music are touching to the ear.” Or again, “There is also an imaginative influence in the voice of the cuckoo, when that voice has taken possession of a deep mountain valley.” Or “We observed the lemon-coloured leaves of the birches, as the breeze turned them to the sun, sparkle, or rather flash like diamonds, and the leafless purple twigs were tipped with globes of shining crystal.” He suggests, moreover, in a curious way, the loneliness of nature; how one may think “of the primaeval woods shedding and renewing their leaves with no human eye to notice, or human heart to regret or welcome the change.” “Flowers, the most brilliant feathers, and even gems, scarcely surpass in colouring some of those masses of stone which no human eye beholds except the shepherd or traveller be led there by curiosity; and how seldom must this happen!”

But a more characteristic passage, perhaps, is that in which he reflects why it is that a lake carries you “into recesses of feeling otherwise impenetrable. The reason of this is that the heavens are not only brought down into the bosom of the earth, but that the earth is mainly looked at and thought of through the medium of a purer element.” A thought like that, he seems to suggest, must be common to every tourist; it is as easy for him to see heaven in the earth as to see grass and stones there. Indeed, his quiet assumption that not only mountains, trees and lakes, but the most minute changes of leaf and herb, are the seriously important things in all lives, amusing as it is at first, persuades us in the end that it is, or should be, really so. For in Wordsworth’s eyes this spectacle of the country-side which we find variously pleasant or delightful as a relief from other things is the most solemn truth that exists. It is no mere curiosity or a taste for the picturesque that drives him to walk out among the hills, and to know all that can be known about the things that grow there. Rather he is trying to read the signs which, whatever their meaning, are to him never made in vain. And, conscious as he is of a beautifully adjusted symmetry in all natural things, his condemnation is most severe of those whose arrogance leads them in any way, by their buildings or plantations, to violate that order. His usual austerity almost breaks into tenderness when he speaks of the little republics of shepherds and farmers which lie among the hills. Theirs was the perfect life whose constitution had been “imposed and regulated by the mountains which protected it”; and theirs, also, were the perfect dwelling places which seem “to have risen, by an instinct of their own, out of the native rock” and “appear to be received into the bosom of the living principle of things”. This belief, so gravely and reverently worshipped, one may almost say, in the live force which lies beneath woods and hills and is perpetually working in them for good, gives to this little book its tone of solemn enthusiasm. You draw from it the impression that a walk among the lakes is to be undertaken in a spirit of reverence, for the sights which rejoice the eye also minister to the soul.

Virginia Woolf (1882-1941): Review of Wordsworth's Guide to the Lakes (ed. Ernest de Sélincourt), from Times Literary Supplement, 15 June 1906

With an Introduction, Appendices, and Notes, textual and illustrative, by ERNEST DE SÉLINCOURT (Frowde. 2s. 6d. net.)

MONTHS AT THE LAKES

By the Rev. H. D. RAWNSLEY (MacLehose. 5s. net.)

Wordsworth wrote his Guide to the Lakes in 1810, to preface a work by the Rev Joseph Wilkinson, who had drawn a folio volume of select views. But the drawings were, as Wordsworth was the first to pronounce, so “intolerable” that he had his preface severed from the main volume and published separately. In spite of its popularity in this shape, however –- some one asked him whether he had written anything else –- the book has not been reprinted as a separate volume since 1864; and many readers will have reason to thank Mr de Sélincourt for his letter of introduction to a new and happily permanent friend. In his excellent preface, which, besides furnishing all facts, suggests the right way of approaching them, Mr de Sélincourt tells us something of the sentimental history of the Lakes. In 1810 they were already the subject of curiosity, although they had not been domesticated in the sense that they are to-day. The people who went went in the conscious spirit of explorers, to bring back tales of what they had seen and to figure hereafter as travellers, rather than as private people who might keep their emotions to themselves. It was the custom to preserve these experiences in prose or verse; but these volumes do not, as Mr de Sélincourt says, “afford invigorating reading.” There was, perhaps, some affectation in their appreciation, and a tendency to approach lakes and mountains with a mind on the defensive against any attacks upon its sensibility. Mountains are “horrid”, and when praise is given, the curiously obsolete and artificial sound of it suggests that it is inspired by a wish to save the writer’s reputation as a man of taste rather than by a simple desire to write the truth.

Wordsworth, coming after these somewhat perplexed and perfunctory tourists, wrote with the calm authority of one who had lived for all but three years of his life among the scenes he describes. He has all the courtesy and consideration of an old inhabitant who does the honours of the place to a stranger, and who not only undertakes to show him the beauties, but will explain from his abundant and well-ordered knowledge any fact of history or geography that seems to him worth observation. He is jealous for his country’s credit, but his familiarity with the place is so perfect that no view will drive him into hasty exaggeration; he admires what he has seen and tested during a life time and knows to deserve and require every word he bestows. At first, it is true, the reader may detect some old-fashioned formality in his guide; he uses still the somewhat rigid vocabulary that was then thought proper for natural things; he will talk of a view that is “rich in a diversity of pleasing or grand scenery”, of “prospects” and “situations”, and he condescends more than a poet should to direct you how best to secure beds at the inn, “as there is but one, and it is much resorted to in summer.” But this very sedateness has its value, and seems to prove that the beauty is real enough to suffer examination by a perfectly candid and conscientious temper. These sober details, moreover, give a tone of solidity to the whole, and suggest the rough surface of the earth, which is as true a part of the country as its heights and its splendours.

Let us station ourselves in a cloud, he begins, hanging midway between Great Gavel or Scawfell; “we shall then see stretched at our feet a number of valleys, not fewer than eight . . . diverging from the point . . . like spokes from the nave of a wheel.” After this general survey he goes on to follow out certain paths in detail, making general observations on the form of the country and gradually narrowing his gaze till he gives us those closely-observed trifles which only a very penetrating eye after long search could have selected and described.

He knows not only the scientific reasons why the rocky part of a mountain is blue or “hoary grey”, with a tinge of red in it “like the compound hues of a dove’s neck”, but also which shade of green is due to the lichen and which to the fern that grows when the first grass is faded. But all through this minute and scrupulous catalogue there runs a purpose which solves it into one coherent and increasingly impressive picture. For all these details and more “which a volume would not be sufficient to describe” are of such interest to him because he sees them all as living parts of a vast and exquisitely ordered system. It is this combination in him of obstinate truth and fervent imagination that stamps his descriptions more deeply upon the mind than those of almost any other writer. “Days of unsettled weather,” he says, “with partial showers, are very frequent, but the showers, darkening or brightening as they fly from hill to hill, are not less grateful to the eye than finely interwoven passages of gay and sad music are touching to the ear.” Or again, “There is also an imaginative influence in the voice of the cuckoo, when that voice has taken possession of a deep mountain valley.” Or “We observed the lemon-coloured leaves of the birches, as the breeze turned them to the sun, sparkle, or rather flash like diamonds, and the leafless purple twigs were tipped with globes of shining crystal.” He suggests, moreover, in a curious way, the loneliness of nature; how one may think “of the primaeval woods shedding and renewing their leaves with no human eye to notice, or human heart to regret or welcome the change.” “Flowers, the most brilliant feathers, and even gems, scarcely surpass in colouring some of those masses of stone which no human eye beholds except the shepherd or traveller be led there by curiosity; and how seldom must this happen!”

But a more characteristic passage, perhaps, is that in which he reflects why it is that a lake carries you “into recesses of feeling otherwise impenetrable. The reason of this is that the heavens are not only brought down into the bosom of the earth, but that the earth is mainly looked at and thought of through the medium of a purer element.” A thought like that, he seems to suggest, must be common to every tourist; it is as easy for him to see heaven in the earth as to see grass and stones there. Indeed, his quiet assumption that not only mountains, trees and lakes, but the most minute changes of leaf and herb, are the seriously important things in all lives, amusing as it is at first, persuades us in the end that it is, or should be, really so. For in Wordsworth’s eyes this spectacle of the country-side which we find variously pleasant or delightful as a relief from other things is the most solemn truth that exists. It is no mere curiosity or a taste for the picturesque that drives him to walk out among the hills, and to know all that can be known about the things that grow there. Rather he is trying to read the signs which, whatever their meaning, are to him never made in vain. And, conscious as he is of a beautifully adjusted symmetry in all natural things, his condemnation is most severe of those whose arrogance leads them in any way, by their buildings or plantations, to violate that order. His usual austerity almost breaks into tenderness when he speaks of the little republics of shepherds and farmers which lie among the hills. Theirs was the perfect life whose constitution had been “imposed and regulated by the mountains which protected it”; and theirs, also, were the perfect dwelling places which seem “to have risen, by an instinct of their own, out of the native rock” and “appear to be received into the bosom of the living principle of things”. This belief, so gravely and reverently worshipped, one may almost say, in the live force which lies beneath woods and hills and is perpetually working in them for good, gives to this little book its tone of solemn enthusiasm. You draw from it the impression that a walk among the lakes is to be undertaken in a spirit of reverence, for the sights which rejoice the eye also minister to the soul.

Virginia Woolf (1882-1941): Review of Wordsworth's Guide to the Lakes (ed. Ernest de Sélincourt), from Times Literary Supplement, 15 June 1906

It's a good job Herdwick Sheep are hardy. Can you spot 3 pregnant ladies high above Grasmere yesterday? #lakedistrict: image via lynda hill @Windermere99, 3 March 2015

Just after sunrise on Ullswater! No warm glow, just lots of minimalist mist. #cumbria lakedistrict: image via Paul Bullen @PaulBullen1, 3 March 2015

It was one of those wild/wonderful days today on the Fairfield Horseshoe #lakeDistrict #WalksAndWaking #sharelakes: image via lynda hill @Windermere99, 3 March 2015

Great shot! "@pete_savin: Deep #UKsnow on the ridge to Dove crag @CumbriaWeather #Lakedistrict": image via CumbriaWeather @CumbriaWeather, 4 March 2015

"@Croftfoot: A moment of calm before the next wintry shower. #cumbriaweather #lakedistrict @FarmersWeekly": image via RoughFellSheep @RoughFellSheep 3 March 2015

Snow awaits #fairfieldhorseshoe #LakeDistrict: image via Pete Savin @pete_savin, 4 March 2015

Kentmere Pike #lakedistrict today: image via Love the Lakes @love_the_lakes, 4 March 2015

Fantastic winter conditions on the #lakedistrict fells today: image via Love the Lakes @love_the_lakes, 4 March 2015

Last one from #kirkstone #lakedistrict #cumbria #theplacetobe: image via Mickledore @walkingcycling, 4 March 2015

Moody shot of Derwentwater #Keswick #lakedistrict: image via Keswick boot co @keswickbootco, 8 March 2015 North West, England

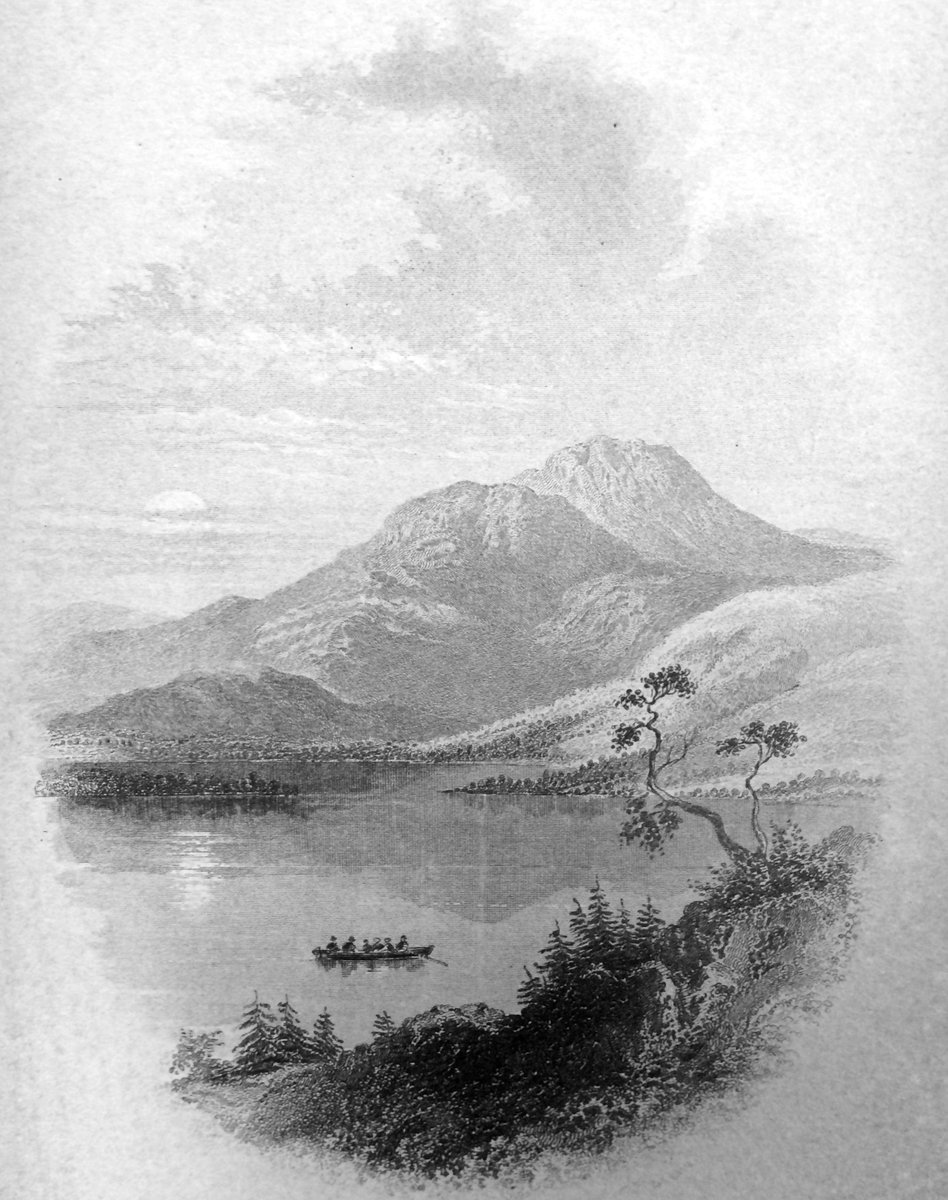

#RomanticismPix #Wordsworth #Windermere: image via villagehistorypics @villagehistory, 24 October 2015

White Out

Rawlins, Wyoming T/A in daylight: photo by aortali1375, 9 February 2008

Coming down out of Ten

Sleep Canyon into Worland

where they still haven't cleared the dust away

from last winter's thirty foot tall drifts

which just melted down and left puddles of

where they still haven't cleared the dust away

from last winter's thirty foot tall drifts

which just melted down and left puddles of

everything that blew through Worland since last Fall

TC: Worland (Worland, Wyoming, March 1980), from A Short Guide to the High Plains, 1981

TC: Worland (Worland, Wyoming, March 1980), from A Short Guide to the High Plains, 1981

Rawlins, Wyoming T/A: photo by aortali1375, 9 February 2008

Rawlins, Wyoming T/A in daylight: photo by aortali1375, 9 February 2008

Spokane I90 Sunday not my trailer: photo by aortali1375, 4 December 2007

Thomas Hardy: Waiting Both

A star looks down at me,

And says: “Here I and you

Stand, each in our degree:

What do you mean to do, --

Mean to do?”

I say: “For all I know,

Wait, and let Time go by,

Till my change come.” -- “Just so,”

The star says, “So mean I,

So mean I.”

Thomas Hardy (1840-1928): Waiting Both, writ early 1920s, first published in The London Mercury, November 1924, collected in Human Shows, Far Phantasies, Songs and Trifles, 1925

A star looks down at me,

And says: “Here I and you

Stand, each in our degree:

What do you mean to do, --

Mean to do?”

I say: “For all I know,

Wait, and let Time go by,

Till my change come.” -- “Just so,”

The star says, “So mean I,

So mean I.”

Thomas Hardy (1840-1928): Waiting Both, writ early 1920s, first published in The London Mercury, November 1924, collected in Human Shows, Far Phantasies, Songs and Trifles, 1925

[Wild Things XI -- Indian Brook]: photo by John Brownlow, 7 February 2006

[Wild Things XI -- Indian Brook]: photo by John Brownlow, 7 February 2006

[Untitled, Indian Brook, Clarksburg, Ontario]: photo by John Brownlow, 14 April 2006

[Untitled, Clarksburg, Ontario]: photo by John Brownlow, 5 July 2006

[Untitled, Thornbury, Ontario]: photo by John Brownlow, 16 October 2006

[Wild Things XXI -- Indian Brook]: photo by John Brownlow, 7 April 2015

Bob Dylan: Don't Think Twice, It's Alright (live c 2001)

ReplyDeleteThis little guy from Minnesota has more fun in the last five minutes of that than that cat dancing in the snow would be having if it were a furry incarnation of Charlie Chaplin dancing in snow in Switzerland.

Bob Dylan: Visions of Johanna (live 2002)

Ah, the old song & dance man...k

ReplyDeleteRemembering now who else would be his age, may I amend my comment to: the self-proclaimed song & dance man. TC forever youngish...k

ReplyDeleteNah, old is old. He must have a secret formula. Us, all we got's the flu, a bent frame, the flu and no bananas, sans hair, sans teeth, sans everything.

ReplyDeleteNot forgetting that the song and dance man is receding rapidly into the past, that was 16/17 years ago, when he was still young and purple.

My Back Pages (live, c. 2001)

But as younger than that now Bobby explains there, I became a Yemeni in the instant that I preached.

(If only!)