Un par de años hará (he perdido la carta), Gannon me escribió de Gualeguaychú anunciando el envío de una versión, acaso la primera española, del poema The Past, de Ralph Waldo Emerson, y agregando en una postdata de que don Pedro Damián, de quien yo guardaría alguna memoria, había muerto noches pasadas, de una congestión pulmonar. El hombre, arrasado por la fiebre, había revivido en su delirio la sangrienta jornada de Masoller; la noticia me pareció previsible y hasta convencional, porque don Pedro, a los diecinueve o veinte años, había seguido las banderas de Aparicio Saravia. La revolución de 1904 lo tomó en una estancia de Río Negro o de Paysandú, donde trabajaba de peón; Pedro Damián era entrerriano, de Gualeguay, pero fue adonde fueron los amigos, tan animoso y tan ignorante como ellos. Combatió en algún entrevero y en la batalla última; repatriado en 1905, retomó con humilde tenacidad las tareas de campo. Que yo sepa, no volvió a dejar su provincia. Los últimos treinta años los pasó en un puesto muy solo, a una o dos leguas del Ñancay; en aquel desamparo, yo conversé con él una tarde (yo traté de conversar con él una tarde), hacia 1942. Era hombre taciturno, de pocas luces. El sonido y la furia Masoller agotaban su historia; no me sorprendió que los reviviera, en la hora de su muerte... Supe que no vería más a Damián y quise recordarlo; tan pobre es mi memoria visual que sólo recordé una fotografía que Gannon le tomó. El hecho nada tiene de singular, si consideramos que al hombre lo vi a principios de 1942, una vez, y a la efigie, muchísimas. Gannon me mandó esa fotografía; la he perdido y ya no la busco. Me daría miedo encontrarla.

—Malas palabras —dijo el coronel—, que es lo que se grita en las cargas.

—Puede ser —dijo Amaro—, pero también gritó ¡Viva Urquiza!

Nos quedamos callados. Al fin, el coronel murmuró:

—No como si peleara en Masoller, sino en Cagancha o India Muerta, hará un siglo.

Agregó con sincera perplejidad:

—Yo comandé esas tropas, y juraría que es la primera vez que oigo hablar de un Damián.

No pudimos lograr que lo recordara.

En Buenos Aires, el estupor que me produjo su olvido se repitió. Ante los once deleitables volúmenes de las obras de Emerson, en el sótano de la librería inglesa de Mitchell, encontré, una tarde, a Patricio Gannon. La pregunté por su traducción de The Past. Dijo que no pensaba traducirlo y que la literatura española era tan tediosa que hacía innecesario a Emerson. Le recordé que me había prometido esa versión en la misma carta en que me escribió la muerte de Damián. Se lo dije, en vano. Con un principio de terror advertí que me oía con extrañeza, busqué amparo en una discusión literaria sobre los detractores de Emerson, poeta más complejo, más diestro y sin duda más singular que el desdichado Poe.

Algunos hechos más debo registrar. En abril tuve carta del coronel Dionisio Tabares; éste ya no estaba ofuscado y ahora se acordaba muy bien del entrerrianito que hizo punta en la carga de Masoller y que enterraron esa noche sus hombres, al pie de la cuchilla. En julio pasé por Gualeguaychú; no di con el racho de Damián,de quien ya nadie se acordaba. Quise interrogar al puestero Diego Abaroa, que lo vio morir; éste había fallecido antes del invierno. Quise traer a la memoria los rasgos de Damián; meses después; hojeando unos álbunes, comprobé que el rostro sombrío que yo había conseguido evocar era el del célebre tenor Tamberlinck, en el papel de Otelo.

Paso ahora a las conjeturas. La más fácil, pero también la menos satisfactoria, postula dos Damianes: el cobarde que murió en Entre Ríos hacia 1946, el valiente, que murió en Masoller en 1904. Su defecto reside en no explicar lo realmente enigmático: los curiosos vaivenes de la memoria del coronel Tabares, el olvido que anula en tan poco tiempo la imagen y hasta el nombre del que volvió. (No acepto, no quiero aceptar una conjetura más simple: la de haber yo soñado al primero.) Más curiosa es la conjetura sobrenatural que ideó Ulrike von Kuhlmann. Pedro Damián, decía Ulrike, pereció en la batalla, y en la hora de su muerte suplicó a Dios que lo hiciera volver a Entre Ríos. Dios vaciló un segundo antes de otorgar esa gracia, y quien la había pedido ya estaba muerto, y algunos hombres lo habían visto caer. Dios, que no puede cambiar el pasado, pero sí las imágenes del pasado, cambió la imagen de la muerte en la de un desfallecimiento, y la sombra del entrerriano volvió a su tierra. Volvió, pero debemos recordar su condición de sombra. Vivió en la soledad, sin una mujer, sin amigos; todo lo amó y lo poseyó, pero desde lejos, como del otro lado de un cristal; “murió”, y su tenue imagen se perdió, como el agua en el agua. Esa conjetura es errónea, pero hubiera debido sugerirme la verdadera (la que hoy creo la verdadera), que a la vez es la más simple y más inaudita. De un modo casi mágico la descubrí en el tratado De Omnipotentia, de Pier Damiani, a cuyo estudio me llevaron dos versos del Canto XXI del Paradiso, que plantean precisamente un problema de indentidad. En el quinto capítulo de aquel tratado, Pier Damiani sostiene, contra Aristóteles y contra Fredegario de Tours, que Dios puede efectuar que no haya sido lo que alguna vez fue. Leí esas viejas discusiones teológicas y empecé a comprender la trágica historia de don Pedro Damián.

Un par de años hará (he perdido la carta), Gannon me escribió de Gualeguaychú anunciando el envío de una versión, acaso la primera española, del poema The Past, de Ralph Waldo Emerson, y agregando en una postdata de que don Pedro Damián, de quien yo guardaría alguna memoria, había muerto noches pasadas, de una congestión pulmonar. El hombre, arrasado por la fiebre, había revivido en su delirio la sangrienta jornada de Masoller; la noticia me pareció previsible y hasta convencional, porque don Pedro, a los diecinueve o veinte años, había seguido las banderas de Aparicio Saravia. La revolución de 1904 lo tomó en una estancia de Río Negro o de Paysandú, donde trabajaba de peón; Pedro Damián era entrerriano, de Gualeguay, pero fue adonde fueron los amigos, tan animoso y tan ignorante como ellos. Combatió en algún entrevero y en la batalla última; repatriado en 1905, retomó con humilde tenacidad las tareas de campo. Que yo sepa, no volvió a dejar su provincia. Los últimos treinta años los pasó en un puesto muy solo, a una o dos leguas del ñancay; en aquel desamparo, yo conversé con él una tarde (yo traté de conversar con él una tarde), hacia 1942. Era hombre taciturno, de pocas luces. El sonido y la furia Masoller agotaban su historia; no me sorprendió que los reviviera, en la hora de su muerte... Supe que no vería más a Damián y quise recordarlo; tan pobre es mi memoria visual que sólo recordé una fotografía que Gannon le tomó. El hecho nada tiene de singular, si consideramos que al hombre lo vi a principios de 1942, una vez, y a la efigie, muchísimas. Gannon me mandó esa fotografía; la he perdido y ya no la busco. Me daría miedo encontrarla.

El segundo episodio se produjo en Montevideo, meses después. La fiebre y la agonía del entrerriano me sugirieron un relato fantástico sobre la derrota de Massoller; Emir Rodrígez Monegal, a quien referí el argumento, me dio unas líneas para el coronel Dionisio Tabares, que había hecho esa campaña. El coronel me recibió después de cenar. Desde un sillón de hamaca, en un patio, recordó con desorden y con amor los tiempos que fueron. Habló de municiones que no llegaron y de caballadas rendidas, de hombres dormidos y terrosos tejiendo laberintos de marchas, de Saravia, que pudo haber entrado en Montevideo y que se desvió, “porque el gaucho teme a la ciudad”, de hombres degollados hasta la nuca, de una guerra civil que me pareció menos la colisión de dos ejércitos que el sueño de un matrero. Habló de Illescas, de Tupambaé, de Maseller. Lo hizo con períodos tan cabales y de un modo tan vívido que comprendí que muchas veces había referido esas mismas cosas, y temí que detrás de sus palabras casi no quedaran recuerdos. En un respiro conseguí intercalar el nombre de Damián.

—¿Damián? ¿Pedro Damián? —dijo el coronel—. Ése sirvió conmigo. Un tapecito que le decían Daymán los muchachos. —Inició una ruidosa carcajada y la cortó de golpe, con fingida o veraz incomodidad.

Con otra voz dijo que la guerra servía, como la mujer, para que se probaran los hombres, y que antes de entrar en batalla, nadie sabía quién es. Alguien podía pensarse cobarde y ser un valiente, y asimismo al revés, como le ocurrió a ese pobre Damián, que se anduvo floreando en las pulperías con su divisa blanca y después flaqueó en Masoller. En algún tiroteo con los zumacos se portó como un hombre, pero otra cosa fue cuando los ejércitos se enfrentaron y empezó el cañoneo y cada hombre sintió que cinco mil hombres se habían coaliado para matarlo. Pobre gurí, que se la había pasado bañando ovejas y que de pronto lo arrastró esa patriada...

Absurdamente, la versión de Tabares me avergonzó. Yo hubiera preferido que los hechos no ocurrieran así. Con el viejo Damián, entrevisto una tarde, hace muchos años, yo había fabricado, sin proponérmelo, una suerte de ídolo; la versión de Tabares lo destrozaba. Súbitamente comprendí la reserva y la obstinada soledad de Damián; no las había dictado la modestia, sino el bochorno. En vano me repetí que un hombre acosado por un acto de cobardía es más complejo y más interesante que un hombre meramente animoso. El gaucho Martín Fierro, pensé, es menos menos memorable que Lord Jim o que Razumov. Sí, pero Damián, como gaucho, tenía obligación de ser Martín Fierro —sobre todo, ante gauchos orientales. En lo que Tabares dijo y no dijo percibí el agreste sabor de lo que se llama artiguismo: la conciencia (tal vez incontrovertible) de que el Uruguay es más elemental que nuestro país y, por ende, más bravo... Recuerdo que esa noche nos despedimos con exagerada efusión.En el invierno, la falta de una o dos circunstancias para mi relato fantástico (que torpemente se obstinaba en no dar con su forma) hizo que yo volviera a la casa del coronel Tabares. Lo hallé con otro señor de edad: el doctor Juan Francisco Amaro, de Paysandú, que también había militado en la revolución de Saravia. Se habló, previsiblemente, de Masoller. Amaro refirió unas anécdotas y después agregó con lentitud, como quien está pensando en voz alta:

—Hicimos noche en Santa Irene, me acuerdo, y se nos incorporó alguna gente. Entre ellos, un veterinario francés que murió la víspera de la acción, y un mozo esquilador, de Entre Ríos, un tal Pedro Damián.

Lo interrumpí con acritud.

—Ya sé —le dije—. El argentino que flaqueó ante las balas.

Me detuve; los dos me miraban perplejos.—Usted se equivoca, señor —dijo, al fin, Amaro—. Pedro Damián murió como querría morir cualquier hombre. Serían las cuatro de la tarde. En la cumbre de la cuchilla se había hecho fuerte la infantería colorada; los nuestros la cargaron, a lanza; Damián iba en la punta, gritando, y una bala lo acertó en el pecho. Se paró en los estribos, concluyó el grito y rodó por tierra y quedó entre las patas de los caballos. Estaba muerto y la última carga de Massoller le paso encima. Tan valiente y no había cumplido veinte años.

Hablaba, a no dudarlo, de otro Damián, pero algo me hizo preguntar qué gritaba el gurí.

—Malas palabras —dijo el coronel—, que es lo que se grita en las cargas.

—Puede ser —dijo Amaro—, pero también gritó ¡Viva Urquiza!

Nos quedamos callados. Al fin, el coronel murmuró:

—No como si peleara en Masoller, sino en Cagancha o India Muerta, hará un siglo.

Agregó con sincera perplejidad:

—Yo comandé esas tropas, y juraría que es la primera vez que oigo hablar de un Damián.No pudimos lograr que lo recordara.En Buenos Aires, el estupor que me produjo su olvido se repitió. Ante los once deleitables volúmenes de las obras de Emerson, en el sótano de la librería inglesa de Mitchell, encontré, una tarde, a Patricio Gannon. La pregunté por su traducción de The Past. Dijo que no pensaba traducirlo y que la literatura española era tan tediosa que hacía innecesario a Emerson. Le recordé que me había prometido esa versión en la misma carta en que me escribió la muerte de Damián. Se lo dije, en vano. Con un principio de terror advertí que me oía con extrañeza, busqué amparo en una discusión literaria sobre los detractores de Emerson, poeta más complejo, más diestro y sin duda más singular que el desdichado Poe.

La adivino así. Damián se portó como un cobarde en el campo de Masoller, y dedicó la vida a corregir esa bochornosa flaqueza. Volvió a Entre Ríos; no alzó la mano a ningún hombre, no marcó a nadie, no buscó fama de valiente, pero en los campos del ñancay se hizo duro, lidiando con el monte y la hacienda chúcara. Fue preparando, sin duda sin saberlo, el milagro. Pensó con lo más hondo: Si el destino me trae otra batalla, yo sabré merecerla. Durante cuarenta años la aguardó con oscura esperanza, y el destino al fin se la trajo, en la hora de su muerte. La trajo en forma de delirio pero ya los griegos sabían que somos las sombras de un sueño. En la agonía revivió su batalla, y se condujo como un hombre y encabezó la carga final y una bala lo acertó en pleno pecho. Así, en 1946, por obra de una larga pasión, Pedro Damián murió en la derrota de Masoller, que ocurrió entre el invierno y la primavera de 1904.

En la Suma Teológica se niega que Dios pueda hacer que lo pasado no haya sido, pero nada se dice de la intrincada concatenación de causas y efectos, que es tan vasta y tan íntima que acaso no cabría anular un solo hecho remoto, por insignificante que fuera, sin invalidar el presente. Modificar no es modificar un solo hecho; es anular sus consecuencias, que tienden a ser infinitas. Dicho sea de con otras palabras; es crear dos historias universales. En la primera (digamos), Pedro Damián murió en Entre Ríos, en 1946; en la segunda, en Masoller, en 1904. Esta es la que vivimos ahora, pero la supresión de aquélla no fue inmediata y produjo las incoherencias que he referido. En el coronel Dionisio Tabares se cumplieron las diversas etapas: al principio recordó que Damián obró como un cobarde; luego, lo olvidó totalmente; luego, recordó su impetuosa muerte. No menos corroborativo es el caso del puestero Abaroa; éste murió, lo entiendo, porque tenía demasiadas memorias de don Pedro Damián.

En cuanto a mí, entiendo no recorrer un peligro análogo. He adivinado y registrado un proceso no accesible a los hombres, una suerte de escándalo de la razón; pero algunas circunstancias mitigan ese privilegio temible. Por lo pronto, no estoy seguro de haber escrito siempre la verdad. Sospecho que en mi relato hay falsos recuerdos. Sospecho que Pedro Damián (si existió) no se llamó Pedro Damián, y que yo lo recuerdo bajo ese nombre para creer algún día que su historia me fue sugerida por los argumentos de Pier Damiani. Algo parecido acontece con el poema que mencioné en el primer párrafo y que versa sobre la irrevocabilidad del pasado. Hacia 1951 creeré haber fabricado un cuento fantástico y habré historiado un hecho real; también el inocente Virgilio, hará dos mil años, creyó anunciar el nacimiento de un hombre y vaticinaba el de Dios.

¡Pobre Damián! La muerte lo llevó a los veinte años en una triste guerra ignorada y en una batalla casera, pero consiguió lo que anhelaba su corazón, y tardó mucho en conseguirlo, y acaso no hay mayores felicidades.

Jorge Luis Borges (1899–1986): La otra muerte (The other death), from El Aleph, 1949

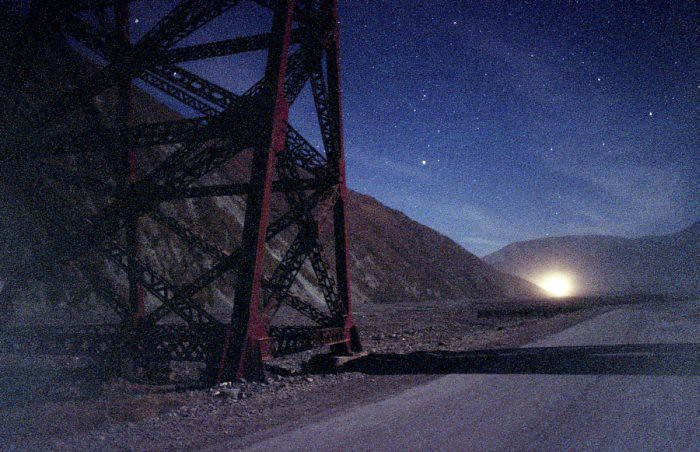

Untitled [Entre Rios, Argentina]: photo by . Lautaro Garcia ., January 2017

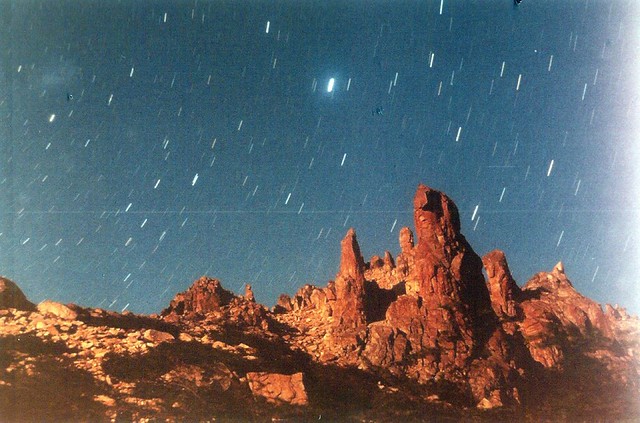

[Provincia de Buenos Aires]: photo by . Lautaro Garcia ., January 2016

Untitled [Provincia de Buenos Aires]: photo by . Lautaro Garcia ., January 2016

Untitled [Medanos, Provincia de Buenos Aires]: photo by . Lautaro Garcia ., January 2015

Untitled [Buenos Aires]: photo by . Lautaro Garcia ., August 2015

Untitled [Buenos Aires]: photo by . Lautaro Garcia ., 21 August 2012

The other death

A couple of years ago perhaps (I have lost the letter), Gannon wrote from Gualeguaychú and announced he would be sending me a version, maybe the first Spanish version, of the poem The Past, by Ralph Waldo Emerson. In a postscript he added that Don Pedro Damián, of whom I would retain some memory, had died the other night from pulmonary congestion. Devastated by fever, the man had relived in his delirium the day-long bloodbath of Masoller. This news seemed predictable, almost conventional, to me, since Don Pedro, when he was about nineteen or twenty, had fallen into the ranks of Aparicio Saravia. The Revolution of 1904 led him to sojourn in Río Negro or Paysandú where he labored on a farm. Pedro Damián was from Entre Ríos, an entrerriano, from Gualeguay to be exact, but went where his chums were, fully participating in their excitement and their ignorance. He fought in a skirmish and then in the final battle. Repatriated in 1905, he reassumed his field laborer duties with humble tenacity. As far as I know, he never again abandoned his native province. He would spend the last thirty years of his life in a very isolated place a league or two from Ñancay.

Around 1942 or so, amidst this state of neglect, I chatted with him

one evening; I should say, I tried to chat with him. He was a taciturn

fellow of feeble intellect. The Masoller sound and fury had swallowed

up all his other narratives, and it did not surprise me that he relived

those memories at the moment of his death. Knowing I would never see Damián

again, I wished to remember him. So poor is my visual memory that I

only recalled a photograph of him which Gannon had taken. There is

nothing strange about this fact if we consider that I saw the man only

once, in early 1942, and then many times in effigy. Gannon sent me this

photograph. I lost it and have not looked for it. I would be afraid

to find it again.

A second episode took place months later in Montevideo. The entrerriano's

fever and agony gave me the idea of writing a fantasy tale about

Masoller's defeat; Emir Rodríguez Monegal, to whom I recounted such a

plot, provided me with a few lines for Colonel Dionisio Tabares, who

had taken part in this campaign. The colonel received me for an

after-dinner talk. From a rocking chair on his patio, he recalled with

little structure but great affection the days that once had been. He

spoke of munitions that never arrived, exhausted horses, sleeping,

earth-colored men weaving in their labyrinthine marches; he spoke of

Saravia, who could have entered Montevideo and who turned off route,

"because that gaucho was scared of the city"; of men whose

throats were cut all the way around their necks; of a civil war that to

me seemed less like a collision of two armies than a crafty gaucho's dream. He talked about Illescas, about Tupambaé, about Masoller. He did so with passages so dignified

and in so lively a manner that I understood that he had mentioned these

same things many times, and I feared that behind his words almost no

memories remained. During a respite I managed to interject Damián's name.

"Damián?

Pedro Damián?" said the colonel. "He served with me. A pansy whom the

boys called Daymán." He let out a loud laugh, then stopped just as

suddenly, either out of feigned or genuine discomfort.

In another voice he said that

war was like a woman: it served as a test for men. And before entering

into battle no one knows who he is. Someone could think himself a

coward and turn out to be valiant; by the same token, the opposite could

occur, which was what happened with poor Damián,

who went prancing around the local stores with his white insignia and

then lost heart at Masoller. In some shootouts with the zumacos,

he comported himself like a man; but it was another matter when the

armies drew up, the cannonade began, and every man felt like five

thousand men had united to kill him. Poor lad, who had spent his days

bathing sheep and who was quickly dragged off by that jingoistic lot.

Absurdly, Tabares's account embarrassed me. I would have preferred that the events had not happened this way. With old Damián

as I had glimpsed him one evening many years ago, I had fabricated,

without intending to do so, a sort of idol; Tabares's account destroyed

it. All of a sudden I understood Damián's reserve and obstinate solitude: these

actions had been dictated not by modesty, but by embarrassment. In

vain I repeated to myself that a man hounded by an act of cowardice was

more complete and more interesting than a man who was merely spirited.

The gaucho Martín Fierro, I thought, was less memorable than Lord Jim or Razumov. Yet if Damián, as a gaucho, were obliged to be Martín Fierro – above all, before eastern gauchos. In what Tabares said and did not say I perceived the rugged flavor of what was called Artiguism:

the (perhaps incontrovertible) awareness that Uruguay was more

fundamental than our country and, in the end, more brave ... That night,

I remember, we bid farewell with exaggerated effusiveness.

In the winter, one or two details for my fantasy tale (which stupidly

was not assuming the needed shape) still eluded me, engendering a

return to the house of Colonel Tabares. I found him with another

gentleman of his age, Doctor Juan Francisco Amaro of Paysandú,

who had likewise taken up arms in Saravia's revolution. Predictably,

they had been talking about Masoller. Amaro recounted a few anecdotes

and then added, slowly like someone thinking aloud:

"I remember we spent the night

in Santa Irene, where some others were incorporated into our ranks: a

French veterinarian who died on the eve of the action, and a young skier

from Entre Ríos, a certain Pedro Damián."

I interrupted him acrimoniously.

"I already know that," I told him. "The Argentine who lost heart before the bullets."

I stopped; the two were gazing at me perplexed.

"You're

wrong, my dear sir," said Amaro finally. "Pedro

Damián died as any man would have wanted to die. It was probably four

o'clock in the afternoon. At the top of the mountain range the Colorado

infantry had made themselves very strong; our troops charged them with

spears. Damián

was at the head of the attack, yelling, and a bullet hit him in the

chest. He stopped his stirrups, concluded his yelling, rolled to the

ground, and remained between the horses' legs. He was dead and the last

charge of Masoller passed right over him. So brave and yet not even

twenty years old.

He was speaking, doubtless, of another Damián, yet something made me ask what the lad was yelling.

"Bad words," said the colonel. "Which is what one yells during a charge."

"That may be," said Amaro. "But he also screamed, 'Viva Urquiza!'"

We remained silent. At length, the colonel mumbled:

"It might be a signal were he not fighting in Masoller, but at Cagancha or at India Muerta."

Sincerely perplexed, he added:

"I commanded these troops, and I would swear this was the first time I heard anyone talk of a Damián."

We could not manage to make him remember.

In Buenos Aires, the stupor

engendered by his forgetfulness was repeated. One afternoon, in front

of eleven delightful volumes of Emerson in the basement of Mitchell's

English library, I met Patricio Gannon. I asked him for the translation

of The Past. He said he did not intend to translate it and

that Spanish literature was so tedious as to make Emerson unnecessary. I

reminded him that he had promised me that version in the same letter in

which he had written about Damián's

death. I told him this, all in vain. In horror I noticed that he was

listening to me with surprise; consequently, I sought refuge in a

literary discussion on Emerson's detractors, on that poet more complete,

more skillful, and undoubtedly more singular than unhappy Poe.

A few facts should be noted.

In April I received a letter from Colonel Dionisio Tabares. He was now

no longer uncertain or obscure and remembered very well the little entrerriano

who had headed the charge of Masoller and who, that same night, had

buried his men at the foot of the mountain range. In July I passed

through Gualeguaychú; I did not pass by Damián's

hut, and no one remembered him. I wanted to ask the rancher Diego

Abaroa, who had seen him die; but he too had died before the winter. I

wanted to etch Damián's features into my memory.

Months later, while leafing through some albums, I realized that the

gloomy face that I had managed to evoke was that of the celebrated tenor

Tamberlinck, in the role of Othello.

Now

I shall run through the conjectures. The most simple, yet also the

least satisfactory, holds that there exist two Damiáns: the coward who

died in Entre

Ríos around 1946, and the hero who died in Masoller in 1904. The flaw

in this conjecture resides in the fact that it does not explain the

truly enigmatic component: to wit, the curious swings in memory on the

part of Colonel Tabares, the oblivion which annuls in little time the

image and the name of the person who had returned. (I do not accept, I

do not wish to accept a conjecture that is too simple: that I had been

dreaming all along.) More curious is the supernatural theory posited by

Ulrike von Kuhlmann. Pedro Damián, said Ulrike, perished in the

battle, and at the moment of his death he begged God to return him to

Entre

Ríos. God hesitated for a second before granting this wish, and he who

had made this wish was already dead, and several men had seen him

fall. God, who cannot change the past, but can change the images of the

past, changed the image of death into that of a faint, and the shade of

the entrerriano returned to his native land. He returned, but

we must remember the shade's condition. He lived in solitude, without a

wife, without friends; he loved and possessed everything, but from far

off, as if from the other side of a crystal. He "died," and his image

was lost like water within water.

This theory is erroneous, but

to me it must have suggested the truth (that which I believe to be the

truth), which is at once the simplest and most unprecedented. In an

almost magical way, I discovered the truth in Peter Damian's treatise De Omnipotentia, the study of which I owe to two verses in Canto XXI of Paradiso,

presenting exactly the problem of identity. In the fifth chapter of

this treatise, St. Damian claims, against Aristotle and against

Fridugisus, that God can make what once was into something that has

never been. I read these old theological discussions and began to

understand the tragic history of Don Pedro Damián.

I divine the truth as follows. Damián

behaved like a coward on the battlefield of Masoller and dedicated his

life to correcting this embarrassing weakness. He returned to Entre Ríos; he did not lift his hand to any man, he did not mark

anyone, he did not seek out a hero's fame. Yet in the fields of Ñancay

he became hard, struggling with the mountain and the untamed estate.

He was preparing, doubtless without knowing it, the miracle. He thought

most deeply: if destiny brings me into another battle, I will know how

to be worthy of it. For forty years he maintained this battle with dark

hope, and in the end fate brought him a battle, at the moment of his

death. It brought it to him in the form of a delirium, but as the

Greeks already knew, we are the shadows of a dream. In his death-throes

he relived his battle and he comported himself like a man, and he

headed the final charge and a bullet hit him in the middle of his

chest. In this way, in 1946, owing to a long-held passion, Pedro Damián

died in the defeat of Masoller, which occurred between the winter and

the spring of 1904.

In the Summa Theologica,

it is refuted that God can make the past into something that has never

been, but nothing is said about the intricate concatenation of causes

and effects, a chain so vast and intimate that perhaps it would not be

possible to annul a single distant fact, as insignificant as it

may be, without invalidating the present. Modification is not the

modification of a single fact; it is the annulment of its consequences,

which have to be infinite. To say this in other words: it is the

creation of two universal histories. In the first one (let us say),

Pedro Damián died in Entre Ríos in 1946; in the second, in Masoller, in 1904.

The latter is what we are now living, but the suppression of the former

was not immediate and produced the incoherencies which I have

mentioned. In Colonel Dionisio Tabares all the different stages were

gathered: in the beginning he remembered that Damián

acted like a coward; later, he forgot him entirely; then, he remembered

his impetuous death. No less corroborative is the case of the ranch

farmer Abaroa; he died, as I understand, because he had too many

memories of Don Pedro Damián.

As far as I'm concerned, I do

not believe I am running a similar risk. I have guessed and recorded a

process not accessible to man, something akin to a scandal of reason;

yet certain circumstances mitigate this fearsome privilege. For the

moment, I am not sure I have always written the truth. I suspect that

in my narrative there are false memories. I suspect that Pedro Damián (if he existed) was not called Pedro Damián,

and that I remember him by this name so as someday to create his story

as suggested to me by the arguments of St. Peter Damian. Something

similar takes place with the poem mentioned in the first paragraph that

versifies on the irrevocability of the past. Until 1951, I believed I

had created a fantasy tale and had recorded a real event for posterity.

So then did the innocent Virgil, two thousand years ago or so, believe

he was announcing the birth of a man and foretold the birth of God.

Poor Damián!

Death took him at the age of twenty in a domestic battle in a sad,

obscure war, and yet he achieved what his heart yearned for, and took a

long time to achieve it, and perhaps there is no greater happiness than

this.

Jorge Luis Borges (1899–1986): La otra muerte (The other death), from El Aleph, 1949; English version by Hadi Deeb

Entre Rios - Argentina.: photo by Jorge Be, 15 April 2015

Paranacito, Entre Rios, Argentina. Foto Viejita / Oldie.: photo by Pablo Ferrari, 5 October 2013

Untitled [Provincia de Buenos Aires]: photo by . Lautaro Garcia ., April 2016

Ralph Waldo Emerson: The Past

The debt is paid,

The verdict said,

The Furies laid,

The plague is stayed,

All fortunes made;

Turn the key and bolt the door,

Sweet is death forevermore.

Nor haughty hope, nor swart chagrin,

Nor murdering hate, can enter in.

All is now secure and fast;

Not the gods can shake the Past;

Flies-to the adamantine door

Bolted down forevermore.

None can re-enter there,—

No thief so politic,

No Satan with a royal trick

Steal in by window, chink, or hole,

To bind or unbind, add what lacked,

Insert a leaf, or forge a name,

New-face or finish what is packed,

Alter or mend eternal Fact.

Ralph Waldo Emerson (1803-1882): The Past, from May-day and other pieces, 1867

Incredble String Band (Robin Williamson | Mike Heron}: The Half Remarkable Question (live tv, London, 28 March 1968)

ReplyDeleteThose other branches and other endings can haunt a man.

ReplyDeleteO it's the old forgotten question

What is that we are part of?

What is it that we are?

Duncan,

ReplyDeleteThe longer the years pile on, the more one is convinced (if they're me) that the maps and stories on which one has relied for understanding the world are in fact always more or less accidental and contingent and that other maps and stories might be made which would perhaps be equally accurate, that these several and divers maps and stories may perhaps be not only bafflingly divergent but even mutually contradictory; and the recognition of all this comes gradually, as a continuous challenge, requiring (demanding!) steady revision, reconsideration, expansion, even questioning and withdrawal of previous conclusions... a process which could go on forever and should and perhaps does instill doubt, modesty, sometimes regret, sometimes mere confusion... unless one is inclined to simply brush aside all evidence that goes contrary to assumption and expectation... which more or less routine and automatic setting-aside (sweeping-away) seems to be the case, "realistically speaking", maybe 99.46% of the time, for approx 98.21% of people.

Uh, if you get what I mean.

Anyhow though I do get how people might want to consider Borges an overly cerebral writer, too interested in intellectual problems, with none of that living warmth of affect, and of gossip, which are thought to make "fiction" come alive; or to regard ISB as a silly bit of dippy hippie fluff, curiously, I find both specimens extremely inspiring, in that strange own-world way which o'ertakes stubborn old age.

The wonderful long exposure night world of distance and solitude and starlight which Lautaro Garcia discovers (creates) in his native place (also JGB's) I take to be just the sort of gift which enlarges the view, in a small way, permanently, once experienced... so that what we are part of, and what we are, are seen, once again, thank the gods, in that slightly new way, for at least a moment... which then of course becomes if only very briefly the most precious of all possible/available moments.

creo que el tema de la muerte es uno de los temas más interesantes y (más difíciles de expresar) que puede tocar un escritor o un poeta...a veces basta una línea para dejarnos pensando en algo que nos une a todos

ReplyDelete"a veces basta una línea para dejarnos pensando en algo que nos une a todos"

ReplyDeletePor lo pronto, no estoy seguro de haber escrito siempre la verdad. Sospecho que en mi relato hay falsos recuerdos. Sospecho que Pedro Damián (si existió) no se llamó Pedro Damián, y que yo lo recuerdo bajo ese nombre para creer algún día que su historia me fue sugerida por los argumentos de Pier Damiani. Algo parecido acontece con el poema que mencioné en el primer párrafo y que versa sobre la irrevocabilidad del pasado. Hacia 1951 creeré haber fabricado un cuento fantástico y habré historiado un hecho real; también el inocente Virgilio, hará dos mil años, creyó anunciar el nacimiento de un hombre y vaticinaba el de Dios.