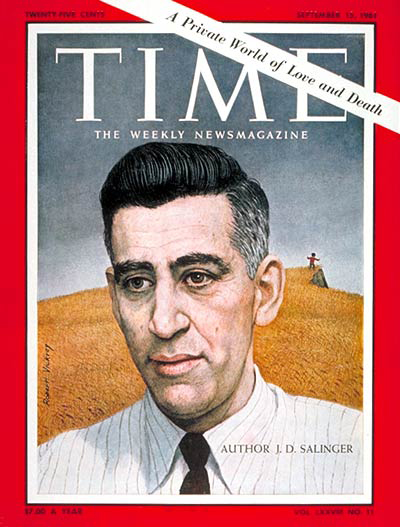

Perhaps the strangest tale of #Borges, La intrusa (The Intruder) #Argentina #BuenosAires #cuentos: image via Hadi Deeb @HadiDeeb, 14 April 2012

Jorge Luis Borges: La intrusa

Dicen (lo cual es improbable) que

la historia fue referida por Eduardo, el menor de los Nelson, en el

velorio de Cristian, el mayor, que falleció de muerte natural, hacia mil

ochocientos noventa y tantos, en el partido de Moran. Lo cierto es que

alguien la oyó de alguien, en el decurso de esa larga noche perdida,

entre mate y mate, y la repitió a Santiago Dabove, por quien la supe.

Años después, volvieron a contármela en Turdera, donde había

acontecido. La segunda versión, algo mas prolija, confirmaba en suma la

de Santiago, con las pequeñas variaciones y divergencias que son del

caso. La escribo ahora porque en ella se cifra, si no me engaño, un breve

y trágico cristal de la índole de los orilleros antiguos. Lo haré con

probidad, pero ya preveo que cederé a la tentación literaria de acentuar

o agregar algún pormenor.

En Turdera los llamaban los Nilsen. El párroco me dijo que su predecesor recordaba, no sin sorpresa, haber visto en la casa de esa gente una gastada Biblia de tapas negras, con caracteres góticos; en las últimas páginas entrevió nombres y fechas manuscritas. Era el único libro que había en la casa. La azarosa crónica de los Nilsen, perdida como todo se perderá. El caserón, que ya no existe, era de ladrillo sin revocar; desde el zaguán se divisaban un patio de baldosa colorada y otro de tierra. Pocos, por lo demás, entraron ahí; los Nilsen defendían su soledad. En las habitaciones desmanteladas durmieron en catres; sus lujos eran el caballo, el apero, la daga de hoja corta, el atuendo rumboso de los sábados y el alcohol pendenciero. Sé que eran altos, de melena rojiza. Dinamarca o Irlanda, de las que nunca oirían hablar, andaban por la sangre de esos dos criollos. El barrio los temía a los Colorados; no es imposible que debieran alguna muerte. Hombro a hombro pelearon una vez a la policía. Se dice que el menor tuvo un altercado con Juan Iberra, en el que no llevó la peor parte, lo cual, según los entendidos, es mucho. Fueron troperos, cuarteadores, cuatreros y alguna vez tahúres. Tenían fama de avaros, salvo cuando la bebida y el juego los volvían generosos. De sus deudos nada se sabe ni de dónde vinieron. Eran dueños de una carreta y una yunta de bueyes.

Físicamente diferían del compadraje que dio su apodo forajido a la Costa Brava. Esto, y lo que ignoramos, ayuda a comprender lo unidos que fueron. Mal quistarse con uno era contar con dos enemigos.

Los Nilsen eran calaveras, pero sus episodios amorosos habían sido hasta entonces de zaguán o de casa mala. No faltaron, pues, comentarios cuando Cristian llevó a vivir con Juliana Burgos. Es verdad que ganaba así una sirvienta, pero no es menos cierto que la colmó de horrendas baratijas y que la lucia en las fiestas. En las pobres fiestas de conventillo, donde la quebrada y el corte estaban prohibidos y donde se bailaba, todavía, con mucha luz. Juliana era de tez morena y de ojos rasgados, bastaba que alguien la mirara para que se sonriera. En un barrio modesto, donde el trabajo y el descuido gastan a las mujeres, no era mal parecida.

Eduardo los acompañaba al principio. Después emprendió un viaje a Arrecifes por no sé que negocio; a su vuelta llevó a la casa una muchacha, que había levantado por el camino, y a los pocos días la echó. Se hizo más hosco; se emborrachaba solo en el almacén y no se daba con nadie. Estaba enamorado de la mujer de Cristian. El barrio, que tal vez lo supo antes que él, previó con alevosa alegría la rivalidad latente de los hermanos.

Una noche, al volver tarde de la esquina, Eduardo vio el oscuro de Cristian atado al palenque. En el patio, el mayor estaba esperándolo con sus mejores pilchas. La mujer iba y venia con el mate en la mano. Cristian le dijo a Eduardo:

—Yo me voy a una farra en lo de Farias. Ahí la tenes a la Juliana; si la queres, úsala.

El tono era entre mandón y cordial. Eduardo se quedó un tiempo mirándolo; no sabía qué hacer, Cristian se levantó, se despidió de Eduardo, no de Juliana, que era una cosa, montó a caballo y se fue al trote, sin apuro.

Desde aquella noche la compartieron. Nadie sabrá los pormenores de esa sórdida unión, que ultrajaba las decencias del arrabal. El arreglo anduvo bien por unas semanas, pero no podía durar. Entre ellos, los hermanos no pronunciaban el nombre de Juliana, ni siquiera para llamarla, pero buscaban, y encontraban, razones para no estar de acuerdo. Discutían la venta de unos cueros, pero lo que discutían era otra cosa. Cristian solía alzar la voz y Eduardo callaba. Sin saberlo, estaban celándose. En el duro suburbio, un hombre no decía, ni se decía, que una mujer pudiera importarle, mas allá del deseo y la posesión, pero los dos estaban enamorados. Esto, de algún modo, los humillaba.

Una tarde, en la plaza de Lomas , Eduardo se cruzó con Juan Iberra, que lo felicitó por ese primor que se había agenciado. Fue entonces, creo, que Eduardo lo injirió. Nadie, delante de él, iba a hacer burla de Cristian.

La mujer atendía a los dos con sumisión bestial; pero no podía ocultar alguna preferencia por el menor, que no había rechazado la participación, pero que no la había dispuesto.

Un día, le mandaron a la Juliana que sacara dos sillas al primer patio y que no apareciera por ahí, porque tenían que hablar. Ella esperaba un dialogo largo y se acostó a dormir la siesta, pero al rato la recordaron. Le hicieron llenar una bolsa con todo lo que tenia, sin olvidar el rosario de vidrio y la crucecita que le había dejado su madre. Sin explicarle nada la subieron a la carreta y emprendieron un silencioso y tedioso viaje. Había llovido; los caminos estaban muy pesados y serian las cinco de la mañana cuando llegaron a Morón. Ahí la vendieron a la patrona del prostíbulo. El trato ya estaba hecho; Cristian cobró la suma y la dividió después con el otro.

En Turdera, los Nilsen, perdidos hasta entonces en la maraña (que también era una rutina) de aquel monstruoso amor, quisieron reanudar su antigua vida de hombres entre hombres. Volvieron a las trucadas, al reñidero, a las juergas casuales. Acaso, alguna vez, se creyeron salvados, pero solían incurrir, cada cual por su lado, en injustificadas o harto justificadas ausencias. Poco antes de fin de año el menor dijo que tenia que hacer en la Capital. Cristian se fue a Moron; en el palenque de la casa que sabemos reconoció al overo de Eduardo. Entró; adentro estaba el otro, esperando turno. Parece que Cristian le dijo:

—De seguir así, los vamos a cansar a los pingos. Más vale que la tengamos a mano.

Habló con la patrona, sacó unas monedas del tirador y se la llevaron. La Juliana iba con Cristian; Eduardo espoleó al overo para no verlos.

Volvieron a lo que ya se ha dicho. La infame solución había fracasado; los dos habían cedido a la tentación de hacer trampa. Caín andaba por ahí, pero el cariño entre los Nilsen era muy grande —¡quién sabe que rigores y qué peligros habían compartido!— y prefirieron desahogar su exasperación con ajenos. Con un desconocido, con los perros, con la Juliana, que había traído la discordia.

El mes de marzo estaba por concluir y el calor no cejaba. Un domingo (los domingos la gente suele recogerse temprano) Eduardo, que volvía del almacén, vio que Cristian uncía los bueyes. Cristian le dijo:

—Veni; tenemos que dejar unos cueros en lo del Pardo; ya los cargue, aprovechemos la fresca.

El comercio del Pardo quedaba, creo, más al Sur; tomaron por el Camino de las Tropas; después, por un desvío. El campo iba agrandándose con la noche.

Orillaron un pajonal; Cristian tiró el cigarro que había encendido y dijo sin apuro:

—A trabajar, hermano. Después nos ayudaran los caranchos. Hoy la maté. Que se quede aquí con sus pilchas. Ya no hará mas perjuicios.

Se abrazaron, casi llorando. Ahora los ataba otro vinculo: la mujer tristemente sacrificada y la obligación de olvidarla.

Jorge Luis Borges (1899-1986): La intrusa (The Intruder), from El informe de Brodie, 1970

2 Reyes, i, 26.

En Turdera los llamaban los Nilsen. El párroco me dijo que su predecesor recordaba, no sin sorpresa, haber visto en la casa de esa gente una gastada Biblia de tapas negras, con caracteres góticos; en las últimas páginas entrevió nombres y fechas manuscritas. Era el único libro que había en la casa. La azarosa crónica de los Nilsen, perdida como todo se perderá. El caserón, que ya no existe, era de ladrillo sin revocar; desde el zaguán se divisaban un patio de baldosa colorada y otro de tierra. Pocos, por lo demás, entraron ahí; los Nilsen defendían su soledad. En las habitaciones desmanteladas durmieron en catres; sus lujos eran el caballo, el apero, la daga de hoja corta, el atuendo rumboso de los sábados y el alcohol pendenciero. Sé que eran altos, de melena rojiza. Dinamarca o Irlanda, de las que nunca oirían hablar, andaban por la sangre de esos dos criollos. El barrio los temía a los Colorados; no es imposible que debieran alguna muerte. Hombro a hombro pelearon una vez a la policía. Se dice que el menor tuvo un altercado con Juan Iberra, en el que no llevó la peor parte, lo cual, según los entendidos, es mucho. Fueron troperos, cuarteadores, cuatreros y alguna vez tahúres. Tenían fama de avaros, salvo cuando la bebida y el juego los volvían generosos. De sus deudos nada se sabe ni de dónde vinieron. Eran dueños de una carreta y una yunta de bueyes.

Físicamente diferían del compadraje que dio su apodo forajido a la Costa Brava. Esto, y lo que ignoramos, ayuda a comprender lo unidos que fueron. Mal quistarse con uno era contar con dos enemigos.

Los Nilsen eran calaveras, pero sus episodios amorosos habían sido hasta entonces de zaguán o de casa mala. No faltaron, pues, comentarios cuando Cristian llevó a vivir con Juliana Burgos. Es verdad que ganaba así una sirvienta, pero no es menos cierto que la colmó de horrendas baratijas y que la lucia en las fiestas. En las pobres fiestas de conventillo, donde la quebrada y el corte estaban prohibidos y donde se bailaba, todavía, con mucha luz. Juliana era de tez morena y de ojos rasgados, bastaba que alguien la mirara para que se sonriera. En un barrio modesto, donde el trabajo y el descuido gastan a las mujeres, no era mal parecida.

Eduardo los acompañaba al principio. Después emprendió un viaje a Arrecifes por no sé que negocio; a su vuelta llevó a la casa una muchacha, que había levantado por el camino, y a los pocos días la echó. Se hizo más hosco; se emborrachaba solo en el almacén y no se daba con nadie. Estaba enamorado de la mujer de Cristian. El barrio, que tal vez lo supo antes que él, previó con alevosa alegría la rivalidad latente de los hermanos.

Una noche, al volver tarde de la esquina, Eduardo vio el oscuro de Cristian atado al palenque. En el patio, el mayor estaba esperándolo con sus mejores pilchas. La mujer iba y venia con el mate en la mano. Cristian le dijo a Eduardo:

—Yo me voy a una farra en lo de Farias. Ahí la tenes a la Juliana; si la queres, úsala.

El tono era entre mandón y cordial. Eduardo se quedó un tiempo mirándolo; no sabía qué hacer, Cristian se levantó, se despidió de Eduardo, no de Juliana, que era una cosa, montó a caballo y se fue al trote, sin apuro.

Desde aquella noche la compartieron. Nadie sabrá los pormenores de esa sórdida unión, que ultrajaba las decencias del arrabal. El arreglo anduvo bien por unas semanas, pero no podía durar. Entre ellos, los hermanos no pronunciaban el nombre de Juliana, ni siquiera para llamarla, pero buscaban, y encontraban, razones para no estar de acuerdo. Discutían la venta de unos cueros, pero lo que discutían era otra cosa. Cristian solía alzar la voz y Eduardo callaba. Sin saberlo, estaban celándose. En el duro suburbio, un hombre no decía, ni se decía, que una mujer pudiera importarle, mas allá del deseo y la posesión, pero los dos estaban enamorados. Esto, de algún modo, los humillaba.

Una tarde, en la plaza de Lomas , Eduardo se cruzó con Juan Iberra, que lo felicitó por ese primor que se había agenciado. Fue entonces, creo, que Eduardo lo injirió. Nadie, delante de él, iba a hacer burla de Cristian.

La mujer atendía a los dos con sumisión bestial; pero no podía ocultar alguna preferencia por el menor, que no había rechazado la participación, pero que no la había dispuesto.

Un día, le mandaron a la Juliana que sacara dos sillas al primer patio y que no apareciera por ahí, porque tenían que hablar. Ella esperaba un dialogo largo y se acostó a dormir la siesta, pero al rato la recordaron. Le hicieron llenar una bolsa con todo lo que tenia, sin olvidar el rosario de vidrio y la crucecita que le había dejado su madre. Sin explicarle nada la subieron a la carreta y emprendieron un silencioso y tedioso viaje. Había llovido; los caminos estaban muy pesados y serian las cinco de la mañana cuando llegaron a Morón. Ahí la vendieron a la patrona del prostíbulo. El trato ya estaba hecho; Cristian cobró la suma y la dividió después con el otro.

En Turdera, los Nilsen, perdidos hasta entonces en la maraña (que también era una rutina) de aquel monstruoso amor, quisieron reanudar su antigua vida de hombres entre hombres. Volvieron a las trucadas, al reñidero, a las juergas casuales. Acaso, alguna vez, se creyeron salvados, pero solían incurrir, cada cual por su lado, en injustificadas o harto justificadas ausencias. Poco antes de fin de año el menor dijo que tenia que hacer en la Capital. Cristian se fue a Moron; en el palenque de la casa que sabemos reconoció al overo de Eduardo. Entró; adentro estaba el otro, esperando turno. Parece que Cristian le dijo:

—De seguir así, los vamos a cansar a los pingos. Más vale que la tengamos a mano.

Habló con la patrona, sacó unas monedas del tirador y se la llevaron. La Juliana iba con Cristian; Eduardo espoleó al overo para no verlos.

Volvieron a lo que ya se ha dicho. La infame solución había fracasado; los dos habían cedido a la tentación de hacer trampa. Caín andaba por ahí, pero el cariño entre los Nilsen era muy grande —¡quién sabe que rigores y qué peligros habían compartido!— y prefirieron desahogar su exasperación con ajenos. Con un desconocido, con los perros, con la Juliana, que había traído la discordia.

El mes de marzo estaba por concluir y el calor no cejaba. Un domingo (los domingos la gente suele recogerse temprano) Eduardo, que volvía del almacén, vio que Cristian uncía los bueyes. Cristian le dijo:

—Veni; tenemos que dejar unos cueros en lo del Pardo; ya los cargue, aprovechemos la fresca.

El comercio del Pardo quedaba, creo, más al Sur; tomaron por el Camino de las Tropas; después, por un desvío. El campo iba agrandándose con la noche.

Orillaron un pajonal; Cristian tiró el cigarro que había encendido y dijo sin apuro:

—A trabajar, hermano. Después nos ayudaran los caranchos. Hoy la maté. Que se quede aquí con sus pilchas. Ya no hará mas perjuicios.

Se abrazaron, casi llorando. Ahora los ataba otro vinculo: la mujer tristemente sacrificada y la obligación de olvidarla.

Jorge Luis Borges: The Intruder

2 Kings, I, 26.

They say (which is improbable) that the story was told by Eduardo,

the younger of the Nelsons, at the wake of Cristian, the elder, who died

a natural death in the 1890s in the administrative area of Morón. What

we can say for certain is that someone heard it from someone else

during that long, lost night between matés, and repeated it to Santiago

Dabove, from whom I heard it. Years later I was told the story again in

Turdera, where it had taken place. In short, this second, somewhat

tidier version, confirmed Santiago's account – albeit with some small

variations and divergences, which is to be expected. I am writing it

now because, if I am not mistaken, it contains the brief and tragic

essence of these remote bordermen of yore. Although I shall write with

integrity, I foresee succumbing to the literary temptation of

accentuating or adding a detail here and there.

In Turdera they were called the Nilsens. The parish priest told me

that his predecessor remembered, not without some surprise, having

espied in their family home a well-worn Bible bound in black with Gothic

lettering; handwritten numbers and dates peppered the last pages. It

was the only book in the house – the hazard-ridden saga of the Nilsens,

lost as everything would eventually be lost. The sprawling house, which

no longer exists, was of unfinished brick; from the hallway two patios

split off, one in red tiles, the other of dirt. Few, as it were, would

enter there; the Nilsens closely guarded their solitude. In the

dismantled rooms they slept on cots. Their luxuries were their horses,

their harnesses, their short-bladed daggers, their lavish Saturday

attire, and their trouble-making alcohol. I know that they were tall

with long, reddish hair. Denmark or Ireland, of which they had never

heard, coursed through the veins of these creoles. The neighborhood

feared The Redheads; it was not impossible that they might have had

someone's death on their conscience. One time, standing back to back,

they brawled with the police. It is said that the younger Nilsen had an

altercation with Juan Iberra and in the end was not the worse off of

the two, which, in our understanding, is rather impressive. They were

herders, towers, rustlers, and sometimes cardsharps. They were renowned

as misers; only with drink and gambling did they become generous. No

one knew anything of their relatives or even where they came from. They

were the owners of a cart and a team of oxen.

Physically they differed from the usual breed that had lent its

outlaw nickname to the Costa Brava. This fact and what we don't know

can help us understand how united they were. To get along poorly with

one of them was to anticipate having two enemies.

The Nilsens were rakes, but

their amorous episodes had hitherto involved the hallway or their

baleful house. There was no lack of commentary, however, when Cristian

went to live with Juliana Burgos. It was true that in this way he was

gaining a servant. But it was no less certain that he plied her with

awful knickknacks and showed her off on holidays, on those poor holidays

in the slums where both the broken and the regal were banned and where,

nevertheless, there was dancing and a lot of light. Juliana had a dark

complexion and almond-shaped eyes; someone only had to glance at her

and she would smile. She was not bad-looking amidst a modest

neighborhood in which work and negligence conspired to wear women out.

At the beginning Eduardo accompanied them. Then he took a trip to Arrecifes

for who knows what type of business; upon his return he brought home a

girl he had picked up on the way back, and a few days later threw her

out. He became more surly; he got drunk only at the grocery store and

didn't socialize with anyone. He was in love with Cristian's woman.

The neighborhood, who perhaps knew this before he did, foresaw with

treacherous happiness the latent rivalry of the brothers.

One night, coming back late

from the corner, Eduardo espied Cristian's dark horse tethered to the

fence. His older brother was waiting for him on the patio in his best

clothes; the woman was coming and going with maté in her hand. Cristian said to Eduardo:

"I'm going out partying at the Farías' place. Here you have Juliana; if you wish, make use of her."

His tone wavered somewhere between commanding and cordial. Eduardo

remained looking at him for a while; not knowing what to do, Cristian

got up, bid farewell to Eduardo but not to Juliana, which was something,

mounted the horse and, without rushing, set off on a trot.

From that night on they shared her. It is possible that no one knew

the details of this sordid union, which exceeded the decencies of the

slums.

The arrangement went well for a few weeks, but it could not endure.

The brothers did not mention Juliana's name to one another, not even to

call her, but instead looked for, and found, reasons so as to disagree.

They argued over the sale of some hides, but what they argued over was

another matter. Cristian tended to raise his voice as Eduardo remained

silent. Without knowing it, they were jealous of one another. In a

harsh suburb a man did not say – not even to himself – that a woman

could matter to him beyond desire and possession, but both of them were

in love. For them, in a way, this was humiliating.

One evening, on Lomas square,

Eduardo crossed paths with Juan Iberra, who congratulated him for having

scored himself such an exquisite female. It was then, I believe, that

Eduardo laid into him. No one could make fun of Cristian in front of

his brother.

The woman would wait for both

of them with animal-like submissiveness; but she could not hide her

preference for the younger brother, who had not refused to participate

yet had also not made her available.

One day they ordered Juliana to bring two chairs to the first patio and not linger there because they had to talk. She anticipated a long conversation and went to take a siesta, but soon thereafter they remembered her. They made her pack a bag with everything she had, not forgetting the glass rosary and the crucifix that her mother had left her. Without explaining a thing to her, they placed her in the coach and undertook a silent and tedious journey. It had rained; the roads were very oppressive and it may have been around five in the morning when they reached Morón. Here they sold her to the madam of a brothel. The deal was already done; Cristian collected the amount and later divided it with his brother.

One day they ordered Juliana to bring two chairs to the first patio and not linger there because they had to talk. She anticipated a long conversation and went to take a siesta, but soon thereafter they remembered her. They made her pack a bag with everything she had, not forgetting the glass rosary and the crucifix that her mother had left her. Without explaining a thing to her, they placed her in the coach and undertook a silent and tedious journey. It had rained; the roads were very oppressive and it may have been around five in the morning when they reached Morón. Here they sold her to the madam of a brothel. The deal was already done; Cristian collected the amount and later divided it with his brother.

In Turdera, the Nilsens,

hitherto lost in the tangle (which was also a routine) of this monstrous

love, wished to renew their old life of men among men. They returned

to their riggings, to their cockpit, to their casual binges. Perhaps at

some point they believed themselves saved; but they would incur, each

for his own part, unjustified or extremely justified absences. Just

before the end of the year, the younger brother said that he had to go

to the capital. Cristian went to Morón;

on the fence of the house we all know he found Eduardo's peach-colored

horse. He entered; inside the other brother was waiting his turn. I

believe Cristian said to him:

"If we keep this up, we are going to tire out the horses. Better that we keep her with us."

He spoke with the madam, produced some coins from his belt, and they

took her away. Juliana went with Cristian; Eduardo spurred on his

peach-colored horse so as not to have to look at them.

They returned to what has

already been mentioned. The infamous solution had failed; both of them

had given in to the temptation of cheating. Cain certainly wandered

through these parts, but the affection between the Nilsens was very

strong – who knew what rigors and perils they had shared! –

and they preferred to vent their exasperation on outsiders. On a

stranger, on the dogs, on Juliana, who had brought them discord.

The month of March was about to end and the heat was not letting up. One Sunday (on Sundays people are supposed to come home early) Eduardo, returning from the grocery store, saw that Cristian was yoking the oxen. Cristian said to him:

The month of March was about to end and the heat was not letting up. One Sunday (on Sundays people are supposed to come home early) Eduardo, returning from the grocery store, saw that Cristian was yoking the oxen. Cristian said to him:

"Come, we have to leave a few hides at the Pardo's place. I've already loaded them; let's take advantage of the fresh air."

The Pardo's business was, I believe, more to the south; they took the Camino de las tropas, the cattle route, then a detour. The field was growing bigger with the night.

They came upon a scrub-land; Cristian took out the cigarette he had lit and said, without the slightest haste:

"To work, brother. The caracaras will help us afterwards. Today I killed her. May she remain here with her clothes and do no more damage."

They embraced, almost crying. Now yet another shackle bound them together: the sad sacrifice of the woman and the obligation to forget her.

Jorge Luis Borges (1899-1986): La intrusa (The Intruder), from El informe de Brodie, 1970; English vrsion by Hadi Deeb

Southern Caracara Polyborus plancas | Huaco, San Juan, Argentina: photo by Joxerra Aihartza, 11 August 2009

Monumento a San Martin en Arrecifes, Provincia de Buenos Aires: photo by Instituto Sanmartiniano, 11 March 2015

Estacion Arrecifes: Carte nomenclador de la estacio: photo by Marcelofx3. 19 April 2011

No comments:

Post a Comment