.

Vietnamese girl, Danang. The combat photographer Dana Stone rented an apartment in Danang where he and his wife lived. He took this picture of a Vietnamese girl from his second-story window: photo by Dana Stone, 1967; image by fredleobrown, 25 February 2007

Sometimes, sleeping at Khe Sanh was like sleeping after a few pipes of opium, a floating and a drifting in which your mind still worked, so that you would ask yourself whether you were sleeping even while you slept, acknowledging every noise above ground, every explosion and every running tremor in the earth cataloging the specifics of each without ever waking. Marines would sleep with their eyes open, with their knees raised and rigid, often standing up on the doze as though touched by a spell. You took no pleasure from sleep there, no real rest. It was a commodity, it kept you from falling apart, the way cold, fat-caked C rations kept you from starving. That night, probably sleeping, I heard the sound of automatic-weapons fire outside. I had no real sense of waking, only of suddenly seeing three cigarettes glowing in the dark without any memory of their having been lighted.

"Probe," Mayhew said. He was leaning over me, completely dressed again, his face almost touching mine, and for a second I thought he had run over to cover me from any possible incoming. (It would not be the first time that a grunt had done that.) Everyone was awake, all of our poncho liners were thrown back, I reached for my glasses and helmet and realized that I'd already put them on. Day Tripper was looking at us. Mayhew was grinning.

"Listen to that fucker, listen to that, that fucker's gonna burn out the barrel for sure."

It was an M-60 machine gun and it was not firing in bursts, but in a mad, sustained manner. The gunner must have seen something, he was firing cover for a Marine patrol trying to get back in through the wire, maybe it was a three- or four-man probe that had been caught in the flare-light, something standing or moving, an infiltrator or a rat, but it sounded like the gunner was holding off a division. I couldn't tell whether there was answering fire or not, and then, abruptly, the firing stopped.

"Let's go see," Mayhew said, grabbing a rifle.

"Don't you go messin' with that out there," Day Tripper said. "They need us, they be sendin' for us. Fuckin' Mayhew."

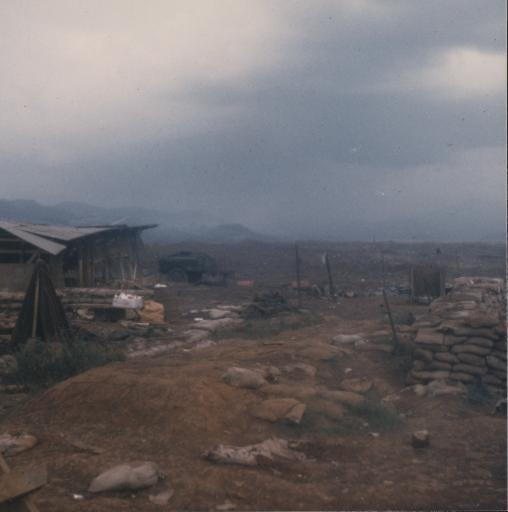

1st Battalion, 26th Marines Headquarters, during the siege of Khe Sanh: photographer unknown, 1968 (John M. Kaheny Collection, U.S. Marine Corps Archives and Special Collections)

.

"Well," the lieutenant said, "you missed the good part. You should have been here five minutes ago. We caught three of them out there by the first wire."

"What were they trying to do?" I asked.

"Don't know. Maybe cut the wires. Maybe lay in a mine, steal some of our Claymores, throw grenades, harass us some, don't know. Won't know, now."

We heard then what sounded at first like a little girl crying, a subdued, delicate wailing, and as we listened it became louder and more intense, taking on pain as it grew until it was a full, piercing shriek. The three of us turned to each other, we could almost feel each other shivering. It was terrible, absorbing every other sound coming from the darkness. Whoever it was, he was past caring about anything except the thing he was screaming about. There was a dull pop in the air above us, and an illumination round fell drowsily over the wire.

"Slope," Mayhew said. "See him there, see there, on the wire there?"

I couldn't see anything out there, there was no movement, and the screaming had stopped. As the flare dimmed, the sobbing started up and built quickly until it was a scream again.

A Marine brushed past us. He had a moustache and a piece of camouflaged parachute silk fastened bandana-style around his throat, and on his hip he wore a holster which held an M-79 grenade-launcher. For a second I thought I'd hallucinated him. I hadn't heard him approaching, and I tried now to see where he might have come from, but I couldn't. The M-79 had been cut down and fitted with a special stock. It was obviously a well-loved object; you could see the kind of work that had gone into it by the amount of light caught from the flares that glistened on the stock. The Marine looked serious, dead-eyed serious, and his right hand hung above the holster, waiting. The screaming had stopped again.

"Wait," he said. "I'll fix that fucker."

His hand was resting now on the handle of the weapon. The sobbing began again, and the screaming; we had the pattern now, the North Vietnamese was screaming the same thing over and over, and we didn't need a translator to tell us what it was.

"Put that fucker away," the Marine said, as though to himself. He drew the weapon, opened the breach and dropped in a round that looked like a great swollen bullet, listening very carefully all the while to the shrieking. He placed the M-79 over his left forearm and aimed for a second before firing. There was an enormous flash on the wire 200 metres away, a spray of orange sparks, and then everything was still except for the roll of some bombs exploding kilometres away and the sound of the M-79 being opened, closed again and returned to the holster. Nothing changed on the Marine's face, nothing, and he moved back into the darkness.

"Get some," Mayhew said quietly. "Man, did you see that?"

And I said, Yes (lying), it was something, really something.

The lieutenant said he hoped that I was getting some real good stories here. He told me to take her easy and disappeared. Mayhew looked out at the wire again, but the silence of the ground in front of us was really talking to him now. His fingers were limp, touching his face, and he looked like a kid at a scary movie. I poked his arm and we went back to the bunker for some more of that sleep.

"The Womb", Khe Sanh. The commissioned officers living quarters, dubbed "The Womb", was destroyed during the siege of Khe Sanh in 1968. The caption on this photograph notes that all occupants were on duty when the bunker was destroyed and no one was injured. The caption also states that the ruined bunker was used "to store the remaining brandy": photographer unknown (John M. Kaheny Collection, U.S. Marine Corps Archives and Special Collections)

.

On the afternoon of the day that we returned to Danang an important press conference was held at the Marine-operated, Marine-controlled press centre, a small compound on the river where most correspondents based themselves whenever they covered 1 Corps. A brigadier general from 3 MAF, Marine Headquarters, was coming over to brief us on developments in the DMZ and Khe Sanh. The colonel in charge of "press operations" was visibly nervous, the dining room was being cleared for the meeting, microphones set up, chairs arranged, printed material put in order. These official briefings usually did the same thing to your perception of the war that flares did to your night vision, but this one was supposed to be special, and correspondents had come in from all over 1 Corps to be there. Among us was Peter Braestrup of the Washington Post, formerly of The New York Times. He had been covering the war for nearly three years. He had been a captain in the Marines in Korea; ex-Marines are like ex-Catholics or off-duty Feds, and Braestrup still made the Marines a special concern of his. He had grown increasingly bitter about the Marines' failure to dig in at Khe Sanh, about their shocking lack of defences against artillery. He sat quietly as the colonel introduced the general and the briefing began.

The weather was excellent: "The sun is up over Khe Sanh by ten every morning." (A collective groan running through the seated journalists.) "I'm glad to be able to tell you that Route Nine is now open and completely accessible." (Would you drive Route 9 into Khe Sanh, General? You bet you wouldn't.)

"What about the Marines at Khe Sanh?" someone asked. "I'm glad we've come to that," the general said. "I was at Khe Sanh for several hours this morning, and I want to tell you that those Marines there are clean!"

There was a weird silence. We all knew we'd heard him, the man had said that the Marines at Khe Sanh were clean ("Clean? He said 'clean', didn't he?"), but not one of us could imagine what he'd meant. "Yes, they're bathing or getting a good wash every other day. They're shaving every day, every single day. Their mood is good, their spirits are fine, morale is excellent and there's a twinkle in their eye!"

Braestrup stood up.

"General."

"Peter?"

"General, what about the defences at Khe Sanh? Now, you built this wonderful, air-conditioned officers' club, and that's a complete shambles. You built a beer hall there, and that's been blown away." He had begun calmly, but now he was having trouble keeping the anger out of his voice. "You've got a medical detachment there that's a disgrace, set up right on the airstrip, exposed to hundreds of rounds every day, and no overhead cover. You've had men at the base since July, you've expected an attack at least since November, they've been shelling you heavily since January. General, why haven't those Marines dug in?"

The room was quiet. Braestrup had a fierce smile on his face as he sat down. When the question had begun, the colonel had jerked suddenly to one side of his chair, as though he'd been shot. Now, he was trying to get his face in front of the general's so that he could give out the look that would say, "See, General? See the kind of peckerheads I have to work with every day?" Braestrup was looking directly at the general now, waiting for his answer -- the question had not been rhetorical -- and it was not long in coming.

"Peter," the general said, "I think you're hitting a small nail with an awfully big hammer."

An ammunition dump struck by a shell explodes in front of U. S. Marines, Khe Sanh: photo by Robert Ellison from cover of Newsweek, 18 March 1968; image by Peer into the Past, 8 April 2013

.

Perhaps, as we claimed, the B-52s had driven them all away, broken the back of their will to attack. (We claimed 13,000 NVA dead from those raids.) Maybe they'd left the Khe Sanh area as early as January, leaving the Marines pinned down, and moved across 1 Corps in readiness for the Tet Offensive. Many people believed that a few battalions, clever enough and active enough, could have kept the Marines at Khe Sanh inside the wire and underground for all of those weeks. Maybe they'd come to see reasons why an attack would be impossible, and gone back into Laos. Or A Shau. Or Quang Tri. Or Hue. We didn't know. They were somewhere, but they were not around Khe Sanh anymore.

Incredible arms caches were being found, rockets still crated, launchers still wrapped in factory paper, AK-47s still packed in Cosmoline, all indicating that battalion-strength units had left in a hurry. The Cav and the Marines above Route 9 were finding equipment suggesting that entire companies had fled. Packs were found on the ground in perfect company formations, and while they contained diaries and often poems written by the soldiers, there was almost no information about where they had gone or why. Considering the amount of weapons and supplies being found (a record for the entire war), there were surprisingly few prisoners, although one prisoner did tell his interrogators that 75 percent of his regiment had been killed by our B-52s, nearly 1,500 men, and that the survivors were starving. He had been pulled out of a spider hole near Hill 881 North, and had seemed grateful for his capture. An American officer who was present at the interrogation actually said that the boy was hardly more than seventeen or eighteen, and that it was hideous that the North was feeding such young men into a war of aggression. Still, I don't remember anyone, Marine or Cav, officer or enlisted, who was not moved by the sight of their prisoners, by the sudden awareness of what must have been suffered and endured that winter.

Michael Herr (1940-): from "Khe Sanh", developed from the Esquire article "Khe Sanh" (September 1969), as revised in Dispatches, 1977

Khe Sanh, 1968. An American C-123 cargo plane burns after being hit by communist

mortars while taxiing on the Marine post at Khe Sanh: photo by Peter Arnett, AP, 1 March 1968; image by mannhai, 3 November 2010

Khe Sanh, March 1968. U.S. Air Force bombs create a curtain of flying shrapnel and debris

barely 200 feet beyond the perimeter of South Vietnamese ranger

positions defending Khe Sanh during the siege of the U.S. Marine base,

March 1968. The photographer, a South Vietnamese officer, was badly

injured when bombs fell even closer on a subsequent pass by U.S.

planes: photo by AP/ARVN, Major Nguyen Ngoc Hanh, March 1968; image by Tan Hiep, 3 November 2010

U.S. sniper team at Khe Sanh, 1968: photo by David Douglas Duncan, in Jack Shulimson, Leonard A Balisol, Charles R. Smith, and David A. Dawson: US Marines in Vietnam: The Defining Year, 1968; Image by RM Gillespie, 18 November 2006; edit by Quibik, 13 September 2009 (US Marine Corps)

U.S. sniper team at Khe Sanh, 1968: photo by David Douglas Duncan, in Jack Shulimson, Leonard A Balisol, Charles R. Smith, and David A. Dawson: US Marines in Vietnam: The Defining Year, 1968; Image by RM Gillespie, 18 November 2006; edit by Quibik, 13 September 2009 (US Marine Corps)

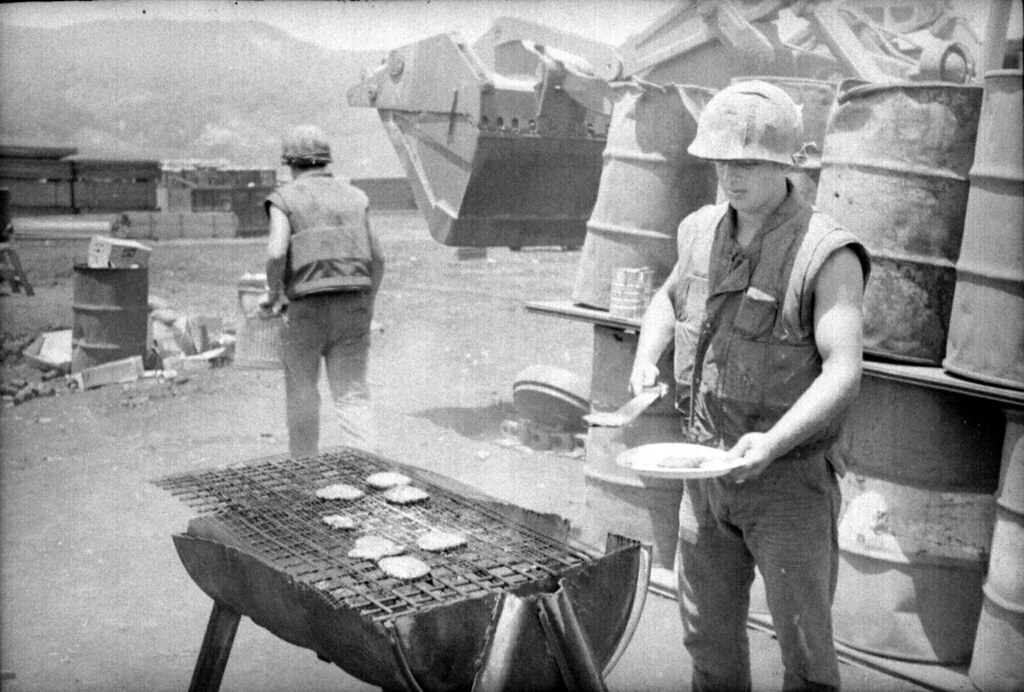

BBQ at Khe Sanh: photo by CBMU 301, March 1968 (U.S. Navy Seabee Museum)

Khe

Sanh post office, during the 77-day NVA siege of the U.S. Marine base:

photo by Dana Stone (1939-?1971), February 1968; image byfredleobrown, 13 January 2008

Khe Sanh (1): In the mist hanging low over this remote bombarded valley, Marines await the next move of the enemy surrounding them: photo by David Douglas Duncan (1916-), Life, 23 February 1968; image by mannhai, 21 September 2012

A U.S. Marine Corps Douglas A-4E Skyhawk from Marine Attack Squadron VMA-121 dropping a napalm canister near Khe Sanh, 1968: Official U.S. Marine Corps photograph in Close Air Support and the Battle for Khe Sanh; image by Cobatfor, 2 November 2012 (U.S. Marine Corps)

Khe Sanh (1): In the mist hanging low over this remote bombarded valley, Marines await the next move of the enemy surrounding them: photo by David Douglas Duncan (1916-), Life, 23 February 1968; image by mannhai, 21 September 2012

A U.S. Marine Corps Douglas A-4E Skyhawk from Marine Attack Squadron VMA-121 dropping a napalm canister near Khe Sanh, 1968: Official U.S. Marine Corps photograph in Close Air Support and the Battle for Khe Sanh; image by Cobatfor, 2 November 2012 (U.S. Marine Corps)

View of a B-52 strike near the U.S. Marine Corps base Khe Sanh, in 1968: photographer unknown; image by Cobatfor, 2 November 2012

Besieged

U.S. Marines at Khe Sanh, Vietnam, watch as a U.S. Air Force McDonnell

F-4 Phantom II makes close air support strike over the area: photo by Sgt. Robert F. Witowski, USAF, March 1968; image by Cobatfor, 9 June 2013

The final evacuation of Khe Sanh base complex: photographer unknown, 1 July 1968; image by HanLing 7 February 2013

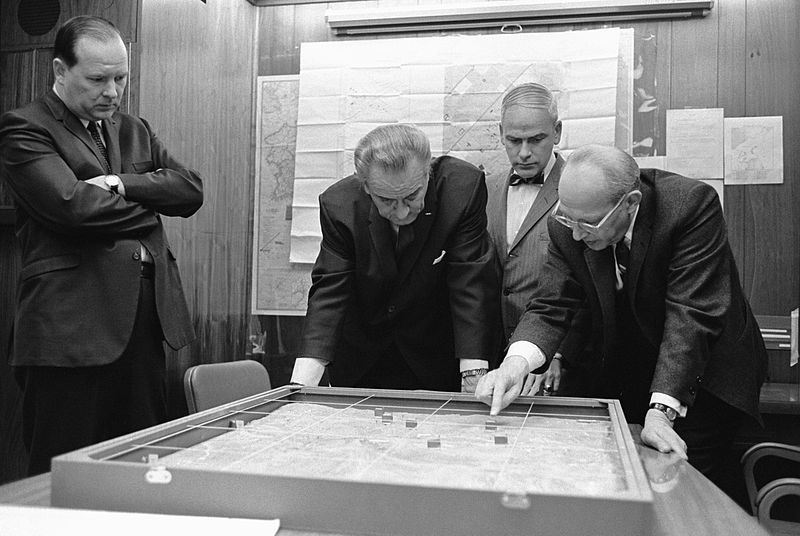

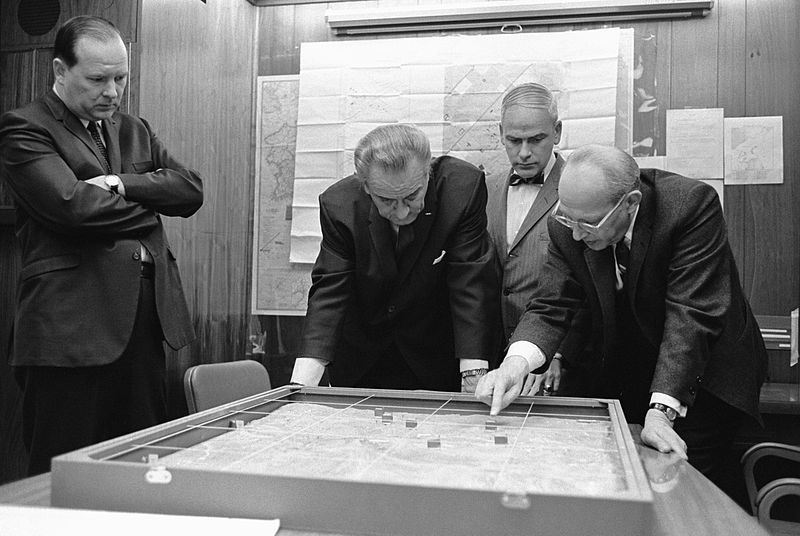

Situation Room: Walt Rostow shows President Lyndon B. Johnson a model of the Khe Sanh area: photographer unknown, 15 February 2008; image by Soerfm, 5 February 2013 (U.S. Department of Defense)

Lorenzo Thomas: Inauguration

Lorenzo Thomas: Inauguration, from Chances Are Few, 1979

Bob Hope, Danang, December 1967. Bob Hope on his way to a Christmas show in Vietnam: photo by Dana Stone, December 1967; image by fredleobrown, 13 January 2008

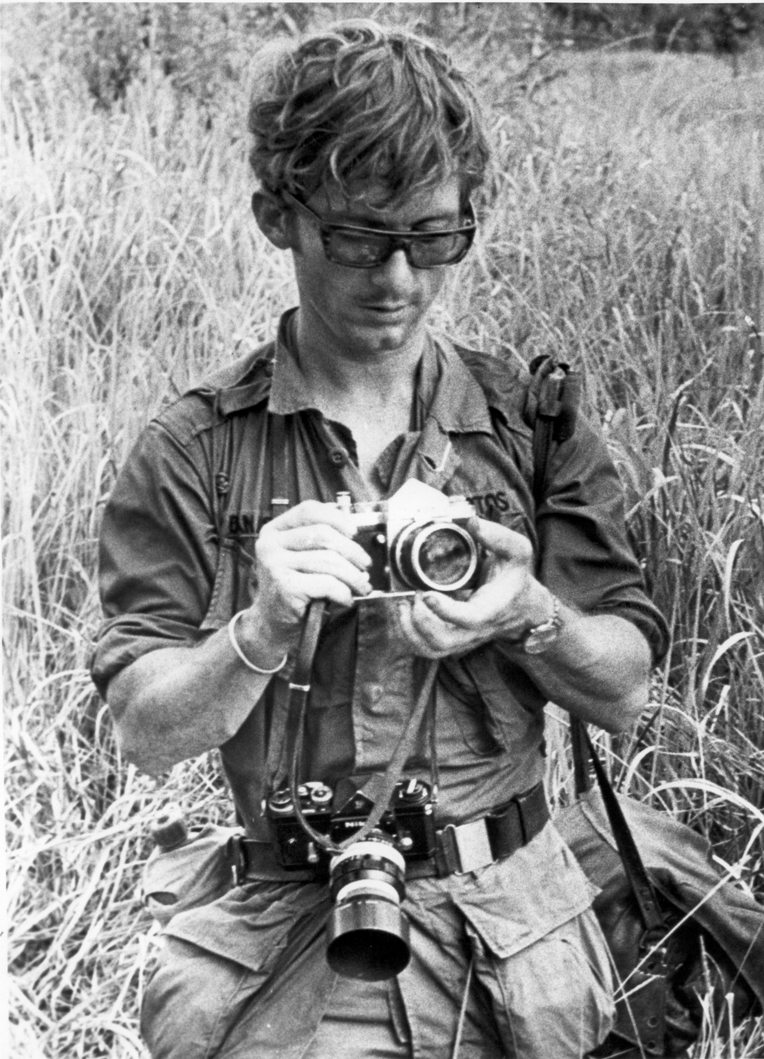

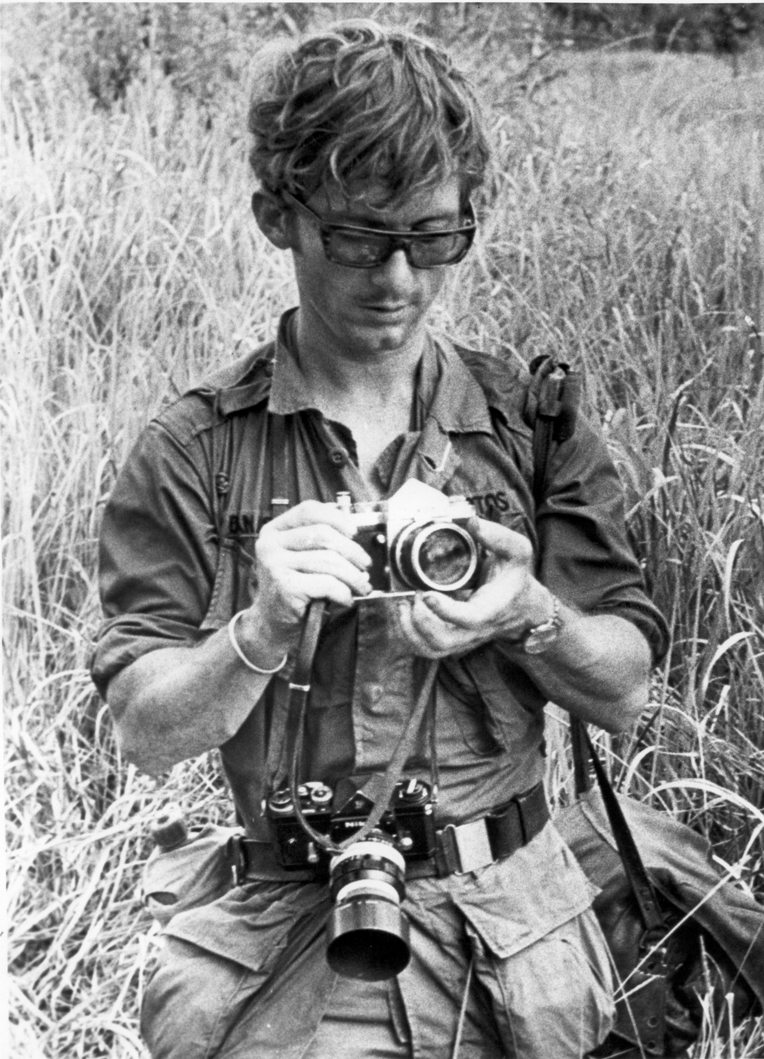

Dana Stone, Vietnam war combat photographer. Stone was captured on April 6, 1970 along with Sean Flynn (son of movie star Errol Flynn) after biking into Cambodia. Remains of neither man were found: photographer unknown, 1967; image by fredleobrown, 11 March 2007

"I don't have any pictures of Dana, but there's not much chance I'll forget what he looked like, that front-line face." -- Michael Herr, Dispatches

A man and a woman watching film footage of the Vietnam War in their living room: photo by Warren K. Leffler, 13 February 1968 (U. S. News & World Report Magazine Photograph Collection, Library of Congress)

Wounded servicemen arriving from Vietnam at Andrews Air Force Base: photo by Warren K. Leffler, 8 March 1968 (U. S. News & World Report Magazine Photograph Collection, Library of Congress)

Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara standing at a podium in front of a map of Vietnam during a press conference: photo by Marion J. Trikosko, 29 June 1966 (U. S. News & World Report Magazine Photograph Collection, Library of Congress)

Lorenzo Thomas: Inauguration

The land was there before us

Was the land. Then things

Began happening fast. Because

The bombs us have always work

Sometimes it makes me think

God must be one of us. Because

Us has saved the world. Us gave it

A particular set of regulations

Based on 1) undisputable acumen,

2) carnivorous fortunes, delicately

Referred to here as “bull market”

And (of course) other irrational factors

Deadly smoke thick over the icecaps,

Our man in Saigon Lima Tokyo etc etc

Lorenzo Thomas: Inauguration, from Chances Are Few, 1979

Bob Hope, Danang, December 1967. Bob Hope on his way to a Christmas show in Vietnam: photo by Dana Stone, December 1967; image by fredleobrown, 13 January 2008

Dana Stone, Vietnam war combat photographer. Stone was captured on April 6, 1970 along with Sean Flynn (son of movie star Errol Flynn) after biking into Cambodia. Remains of neither man were found: photographer unknown, 1967; image by fredleobrown, 11 March 2007

"I don't have any pictures of Dana, but there's not much chance I'll forget what he looked like, that front-line face." -- Michael Herr, Dispatches

A man and a woman watching film footage of the Vietnam War in their living room: photo by Warren K. Leffler, 13 February 1968 (U. S. News & World Report Magazine Photograph Collection, Library of Congress)

Wounded servicemen arriving from Vietnam at Andrews Air Force Base: photo by Warren K. Leffler, 8 March 1968 (U. S. News & World Report Magazine Photograph Collection, Library of Congress)

Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara standing at a podium in front of a map of Vietnam during a press conference: photo by Marion J. Trikosko, 29 June 1966 (U. S. News & World Report Magazine Photograph Collection, Library of Congress)

chuck (see full photo-caption below): photo by daveotuttle, 10 September 2010

this is chuck.

he lived across from me my last year in college.

his shirt says United States Marine Corps.

he wore that shirt every day.

his mullet says don't fuck with me and his eyes back it up.

he was pissed off at the world.

he wouldn't forget to let you know it.

and he drank.

a lot.

and yet...yet Chuck was just a kid.

a kid that grew up too fast in the chaos and war of Vietnam.

a kid that couldn't reconcile that chaos and a return to the world.

a kid who said he never spoke about "those days" yet would tell my friend Rob and I countless stories of his time spent at war, battles fought for indiscriminate points in the jungle, of endless marches through ambush after ambush, the battle and siege waged at Khe Sanh, would show us photographs of the many friends who died until his eyes overflowed with tears and his voice cracked with pain and he inevitably grabbed a handgun pointing it at and yelling at us to get the fuck out of his place, constantly battling the demons in his head.

i liked chuck.

he was a major asshole.

and i respected him.

i don't support war, and i don't support politicians that invent war for their own purposes, but i support our troops and wish a speedy and safe homecoming to them all.

he lived across from me my last year in college.

his shirt says United States Marine Corps.

he wore that shirt every day.

his mullet says don't fuck with me and his eyes back it up.

he was pissed off at the world.

he wouldn't forget to let you know it.

and he drank.

a lot.

and yet...yet Chuck was just a kid.

a kid that grew up too fast in the chaos and war of Vietnam.

a kid that couldn't reconcile that chaos and a return to the world.

a kid who said he never spoke about "those days" yet would tell my friend Rob and I countless stories of his time spent at war, battles fought for indiscriminate points in the jungle, of endless marches through ambush after ambush, the battle and siege waged at Khe Sanh, would show us photographs of the many friends who died until his eyes overflowed with tears and his voice cracked with pain and he inevitably grabbed a handgun pointing it at and yelling at us to get the fuck out of his place, constantly battling the demons in his head.

i liked chuck.

he was a major asshole.

and i respected him.

i don't support war, and i don't support politicians that invent war for their own purposes, but i support our troops and wish a speedy and safe homecoming to them all.

Team 116 near Khe Sanh, 1968: photo by Jalan's Place, 11 May 2013

Khe Sanh Memorial: photo by Paul Seventy, 2 February 2007

The Siege of Khe Sanh and the Tet Offensive, 1968

ReplyDeleteI'h holding the images of Bob Hope and Chuck together in my head.

ReplyDeleteThe sense of sleep as a "commodity".

Because

Us has saved the world. Us gave it

a particular set of regulations

Based on 1) indisputable acumen,

2) carnivorous fortunes.

For me, it's the picture of Robert McNamara looking flummoxed and frustrated behind the 1960s podium in front of the pre-back-projection-era paper map and chart, that makes the whole Vietnam exercise seem so abstract from US mainland reality, while of course it was everything but abstract to US citizens at home and our troops and the Vietnamese caught in its net. We tried to explain Vietnam to Jane again today, but it’s really difficult in a way that explaining the dismantling of the Berlin Wall isn't. It’s so appropriate to have Bob Hope's picture here, but again, trying to explain Bob Hope to a contemporary 16-year old is also challenging. It's very hard to "relive" this, as you’ve made us do, but I've always thought it must have been the worst possible thing to really live it in situ. I haven’t thought about Sean Flynn for quite some time, but I used to a lot. When people disappear and are never seen again, you can’t really grasp that easily. I recently saw Full Metal Jacket again; even though it’s only a movie, it goes off like a repeating gun again and again in your head. My friends and I were all terrified about being drafted (when the relevant time arrived, I drew a high lottery number and was safe from that), and this assemblage brings back so vividly why that was. Lorenzo Thomas was quite a poet. I just remember in the newspapers I read in my luxurious college library, “Khe Sanh; Khe Sanh.” A friend of mine is a history professor at Lafayette University in Easton, PA. I once objected to it when he referred to his students as “the morons.” (To be fair to him, he was under quite a bit of pressure at the time.) I asked him why he called them that and he told me a story about one of his students – one he liked and referred to as a star – who asked him whether or not it was true that Nixon got a raw deal. My friend said, no, he really didn’t think so, that Nixon was pardoned when people who worked for him went to jail, but that the kid didn’t seem to get it. I asked my friend what made this student more exceptional than the others and he told me that it was remarkable that the kid knew who Nixon was. He said that most of his students had no idea who Reagan was. And this was a while ago. Time fades away, as the song goes. Curtis

ReplyDeleteIt's hard to stop looking at these photos and also hard to keep looking at them (all of them), but in some ways the final one of the memorial showing the children standing around it that makes me the saddest.

ReplyDeleteCurtis

Duncan and Curtis,

ReplyDeleteThanks for pausing with me to look back. (At this stage I can use all the help available, if only to remind me to look three times before crossing over.)

Bob Hope, Chuck, Reagan, Nixon, Robert McNamara -- it all runs together, and narrows down to that.

The Ancient History App.

Not a great hit on Smartphones.

Dwelling upon this holiday of ritual cultural forgetting, it is hard not to feel the sadness of the terrible loss of anything approaching an understanding of the trajectory of descent that led us toward a universe dominated by instant messaging, Alexa Chung and Robin Thicke.

In any case, for better or worse (and at this moment I can't recall the better), these were the times and images which bent "my generation" out of shape, and I'll never be able to not remember the early months of 1968.

We had just married, lost what little we owned in a catastrophic Ohio turnpike wreck, and ended up stranded in the Colorado Springs airport (long story), among a throng of the most frightened-looking young men I'd ever seen, all in military greens, all en route to Southeast Asia as part of the great wave of troop callups that came with Tet.

Hi Tom (and Duncan):

ReplyDeleteWhat you wrote (Tom):

"Dwelling upon this holiday of ritual cultural forgetting, it is hard not to feel the sadness of the terrible loss of anything approaching an understanding of the trajectory of descent that led us toward a universe dominated by instant messaging, Alexa Chung and Robin Thicke."

and the rest really sums it up and begs no punctuation or extension.

It reminded me, though, of something that came up on Friday. The law client who relies on me most regularly has been very insistent that we conclude a pending real estate transaction asap. Running the other side's lawyer to ground has been difficult; like I am, he's a free agent, on-the-clock, and is juggling multiple obligations. I pleaded with him that we really try to conclude things by tomorrow and he said that would probably be achievable because courts and banks were closed on Veteran's Day.

Having lived in uber-aleatory world for some time, I had forgotten about this. Jane's school is open; tv doesn't mention it, etc. It's really another big change from my childhood and another example of things slipping down notches and honor becoming merely a Scrabble word.

I'm really out of touch with most of the current scene, but I remember pretty acutely the World War I poetry I first experienced against the backdrop of the Vietnam War and its effect on me.

Right now, with Twitter's IPO being story of the day, rather than the abomination that is Twitter, and other abominations being glossed over daily, to quote Lou Reed, "I guess that I just don't know."

But I think that if remembering and trying to honor the memories of those who served (the ones you knew and the ones you didn't) is all you can do, you should do it.

I met the brother of one of my college roommates after his discharge from Vietnam service. My roommate was an interesting guy -- a Penn State football player who transferred to my college, Swarthmore, a big switch, because he discerned that the different direction was better for him. (As you can imagine, his presence gave our football team -- we had one then -- a real shot in the arm.) Stan's brother Connie said that the day he arrived in Vietnam they were looking for volunteers to be chaplains' assistants. Connie felt that was likely to be the safest place to be -- you were largely called in to nasty places on an after-the-fact basis -- and he was right. For what it's worth, he seemed to be one of the most intelligent, best-adjusted people I had ever met and I felt really neurotic and self-indulgent in his presence.

Curtis

Curtis,

ReplyDeleteHaving joined the elite ranks of the shut-in amateur historians, I've spent an awful lot of time over the past several decades burrowing through the literature of that war. Most of it is not so good, but the narratives tend to form overlays after a while, and one realizes this is a composite history, and a complex subject -- one that matters.

That war probably didn't have a Stephen Crane but it had Michael Herr, whose work gets stronger with the passage of the years.

You may recall this bit on the horrendous Battle of Dak To, the way the 173d Airborne spent Veteran's Day 1967:

Michael Herr: Dislocation (The Battle of Dak To, 1967)