.

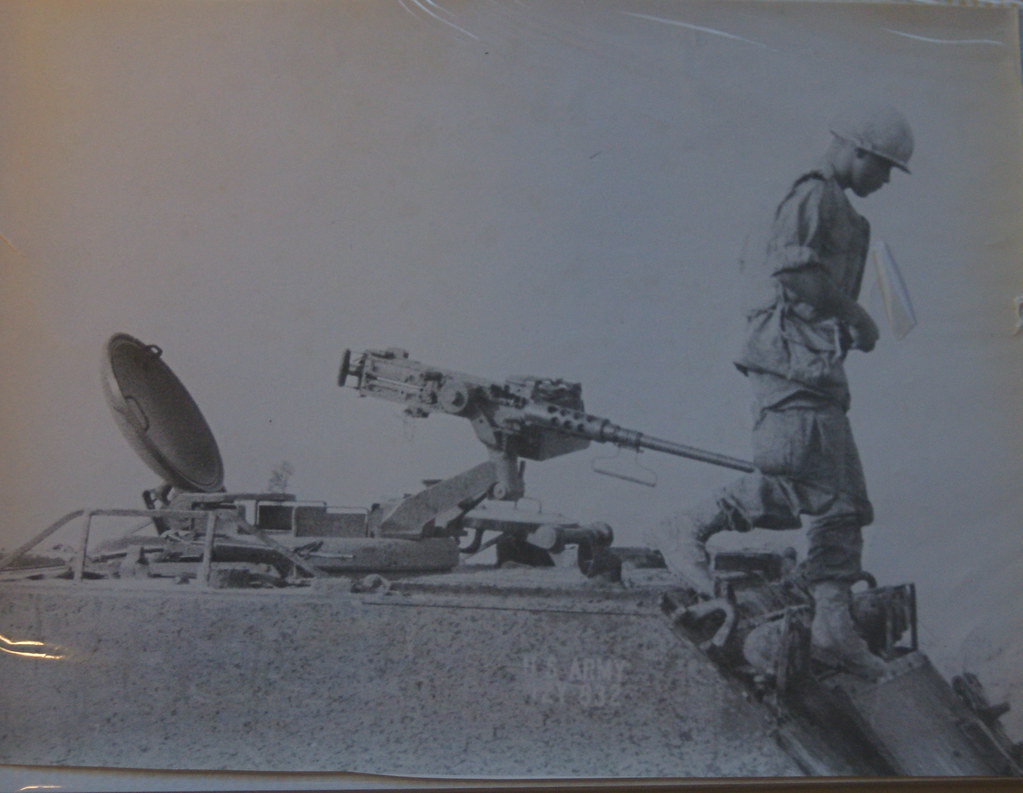

[Untitled, Vietnam]: photo by Clare Love (clare_love42), c.1968; posted 13 September 2008

Of mechanized arms and the man: from an interview with Larry Heinemann, author of Close Quarters (1977):

Q:

What did you want to say [in Close Quarters]?

Heinemann:

I always tried to talk about the war in terms of the work. It seemed like

a good place to start. What struck me about Moby Dick was that

Melville talked about what the work was so that you get an honest to God

appreciation. There is a reason why the passing of that work is not

mourned. Rowing after whales. You’re engaged in slaughterhouse work and

you’re up to your eyeballs in blood. I started writing Close Quarters

in 1968. I’ll hang the story on the work, the same as Melville. It struck

me that folks back here not only did not know what it was like to be in an

Army barracks, but also knew nothing about the war as work. In every sort

of work there is a literal physical satisfaction that comes over you when

a job’s well done, a personal pride. But if you’re an infantryman, your

job is to kill people. “Close and engage” the lifers call it. I’ve heard

historians refer to it as “state sanctioned murder.” But it’s still

murder. And how can you possibly have any good feeling about that? The

aftermath of a firefight is all exhaustion, and downrange it’s all meat.

In half an afternoon you are standing in a smell like no other in the

world. The stink of body count corpses.

I was in

mechanized infantry, a sort of junior armored cavalry. We had APCs,

armored personnel carriers. Tracks. What exactly was the work? Well,

there’s a .50 caliber machine gun that weighs about a hundred pounds and

throws a slug about the size of your thumb and can blow your head off at a

mile. Joseph Heller’s Snowden in Catch-22 was a fifty gunner.

That’s what they used to shoot down Messerschmidts. A very serious weapon.

I had never seen an APC before, but learned quickly because I was the

driver. I was in a recon platoon, so we had four guys on each track. If

you fuck up, three guys hump. You hump, but they hump, too. On the back

were two M-60 machine guns. Basically, you’re driving around in a 13-ton

bunker. We had Chevy 283 V-8s with a four-barrel carburetor and a blower

about the size of a room fan and a 90-gallon gasoline tank. So, you’re

always messing with machinery.

So I told

stories about night ambushes, search and destroy missions, and firefights

large and small. What you do with body count. Smoking grass, drinking

ourselves stupid. I never heard the word marijuana until I went to

Vietnam, and we smoked it all the time. Stories about how the war worked,

the same as you would go at any strange “process.” It’s the same in Robert

Mason’s Chickenhawk. He talks about what a helicopter is, for what,

the first 60 or 70 pages? And if there’s one symbol of Vietnam it’s the

Huey chopper. Mason called it “hauling ass and trash.” We just hauled

ass.

Q:

I remember a famous photograph of a truck pulling VC bodies behind it.

Heinemann:

I don’t need to see the picture. We did that a time or two. You get in a

firefight and afterwards go out and do what we referred to as a dismount,

just like the cavalry. Searching the bodies and making the count. You tie

the heels together with commo wire, which is like extension cord, and drag

them out to the road and leave them. There were some outfits that left

playing cards but we never bothered with that. The strong inference was,

“Fuck with us and this will happen to you.” Sometimes we had to drag the

bodies a good long way. That’s what got to me about reading The Iliad.

Achilles ties Hector’s corpse to a pair of horses. He gives them a whack

on the ass and Hector’s body get dragged round and round the city until

there was nothing left but what was tied at the ankles. How’s that for

“fuck you?”

We had maybe

ten thousand rounds of ammunition, which will last you all day. Crates of

hand grenades. M-79 grenade launchers with both high explosive rounds and

canister rounds, which were 40-millimeter casings with double ought buck

shot. The barrel was eight or nine inches long so you’re walking around

with a serious sawed-off shotgun. The M-16s back in those days were junk.

I took an M-16 on my first ambush and fired three rounds and it jammed.

Fuck this. So after that I took the M-60, the pig, we called it. You

really did carry it like Sylvester Stallone (laughs). You tied a long

strap to the barrel and the butt plate and slung it over your shoulder,

and you’ve got Pancho Villa style bandoleers of ammunition. I had a

12-gauge shotgun for a while, and then an AK-47, which has be the best in

the world.

You couldn’t

keep an M-16 clean enough. If I ever run into the motherfucker that sent

that rifle overseas, I’m going to make short work of him. The other

motherfucker I want to talk to is the asshole who sent gasoline-powered

APCs. Just behind the driver is a 90-gallon gasoline tank. An engineer

told me one gallon of gasoline is equivalent to 19 pounds of TNT and 19

pounds can blow the back of this house off.

Q:

How effective was the armor?

Heinemann:

It’s inch and a quarter aluminum alloy. Small arms fire will ricochet. My

track was all nicked up. By the way, it’s the same armor that they make

the Bradley Fighting Vehicle the Army uses nowadays. And they’re both

deathtraps. A rocket propelled grenade will go through inch and half

aluminum alloy armor plate like spit through a screen. You hit the gas

tank, the track goes up like the head of a match, mushroom cloud and all.

Happened more than once. The drivers had their bodies separated from their

heads. Many drivers got killed or burned to death. I ever run into the

fucking genius who sent gas-powered to Vietnam, he and I are going to have

a serious discussion. I would gladly do time in prison for the chance of

showing Mr. Genius what I think of his scheme.

Q:

Diesel wouldn’t do the same thing?

Heinemann:

Diesel will burn but it takes more to get it going. The only trick we had

was to keep the tank full. That was the myth anyway. The RPG round has a

magnesium core which burns of itself because it carries its own oxygen. So

if you get whacked with an RPG, the shrapnel will burn right through you.

Lots of casualties from that.

Q:

It sounds like complicated machinery didn’t work very well. What did work?

Heinemann:

We used our bayonets to clean our nails and open our mail. Shotguns never

failed. The M-79s were much coveted. The .45 pistols weren’t much good

beyond 25 or 30 feet but looked stylish. A lot of guys had personal

weapons. A good friend of mine’s father gave him a hand-made Bowie knife.

We drove our tracks hard, but they were beaters to start with.

Larry Heinemann in conversation with Kurt Jacobsen, from Logos 2.1, Winter 2003

5th of the 60th [M113 acav APC 5/60th Mechanized Infantry "Bandido Charlie"]. Not sure who the driver was. South of Tan An: photo by Moosejaw2, n.d., posted 27 November 2012

M113 acav 11 ACR "Blackhorse". The 11th Armored Cavalry troops move into position through heavy jungle grass in Vietnam, July 1967 (Al Chang Collection): image by Jerzy Krzeminski, 16 April 2007

Road to My Tho. Along the road between Dong Tam, "home" to the 9th Infantry

Division, and the city of My Tho in Dinh Tuong Province in Vietnam's

Mekong delta in 1968. I shot this with an old Practiflex 35mm camera

while riding in a 1 1/4 ton truck up this road: photo by Lance Nix (Lance and Cromwell), November 1968

M113 acav ""E" troop 11 ACR "Blackhorse". Track "C-20". Vietnam, September 1968 (Don McPhail Collection): image by Jerzy Krzeminski, 8 June 2012

M113 acav ""C" troop 11 ACR "Blackhorse". Unknown fire support base in Vietnam (James J. Trier Collection): image by Jerzy Krzeminski, 27 April 2012

M113 acav "B" troop 17th Cavalry, 82nd Airborne Division "All American". Track "B-34". Somewhere in Vietnam, author unknown: image by Jerzy Krzeminski, 8 June 2012

M113 acav "K" troop 11 ACR "Blackhorse". Vietnam '66-67 (Henry David McInnis Collection): image by Jerzy Krzeminski, 7 September 2012

M113 acav "K" troop 11 ACR "Blackhorse". Vietnam '66-67 (Henry David McInnis Collection): image by Jerzy Krzeminski, 7 September 2012

M113 acav "A" troop 3/5th Cavalry "Black Knights" 9th Infantry Division "Old Reliables". Near Quang Tri on the DMZ border -- patrol along the 17th Parallel. Vietnam, 1971 (Bruno Barbey Colection): image by Jerzy Krzeminski, 24 August 2012

M113 acav "A" troop 3/4th Cavalry 25th Infantry Division "Tropic Lightning". Unknown fire support base -- Cu Chi? Vietnam '66-'67 (Phil Hogue Collection): image by Jerzy Krzeminski, 1 October 2012

M113 acav 11 ACR "Blackhorse". U.S. soldiers of an armored unit dig in as they advance into Cambodia, about 10 miles north of Katum base in South Vietnam, in May 1970 (Henri Huet Collection): photo 1 May 1970; image by Jerzy Krzeminski

M113 APC "B" Company 1/5th Infantry "Bobcats" 25th Infantry Division "Tropic Lightning". Vietnam '70-'71 (Mike Smith Collection): image by Jerzy Krzeminski, 1 October 2012

M132 zippo track 919th Engineer Company "Red Devils" 11 ACR "Blackhorse". Vietnam '69-'70 (R.C. Perea Collection): image by Jerzy Krzeminski, 14 August 2012

[Untitled, Vietnam]: photo by Bandido Charlie 36, n.d., posted 27 November 2012

Two Charlie Company tracks leaving Tay Ninh base camp after a three day standdown: photo by Mario Tarin (mariotarin63), c. 1969-1970, posted 1 January 2008

Two Charlie Company tracks leaving Tay Ninh base camp after a three day standdown: photo by Mario Tarin (mariotarin63), c. 1969-1970, posted 1 January 2008

APC with .50 cal. going through Bien Hoa, 1967: photo by William Harrell (7th Surgical Hospital), 1967

A Duster with twin 40 mm guns passing by between the battalion aid station and the ammo dump, Tan Tru, Long An, Vietnam: photo by Dennis 2nd/60th/9th, 1968; posted 3 August 2009

M113 acav 11 ACR "Blackhorse". Probably 919th Engineer Company "Red Devils". Vietnam ['69-'70] (Chester Brozozowski Collection): image by Jerzy Krzeminski, 21 June 2012

5th of the 60th Mechanized Infantry, 9th Division. Traveling through Tan An on the way to the air strip: photo by Moosejaw2, n.d., posted 20 December 2012

M-113 "D" Company 16th Armor 173rd ABN. Vietnam (Jacob Thomas Collection): image by Jerzy Krzeminski, 4 August 2013

M113 acav "E" troop 1/1st cavalry 23rd Infantry Division "America!" Somewhere in Vietnam (Thomas Dovine Collection): image by Jerzy Krzeminski, 24 August 2013

M113 acav 1/61st Infantry Division "Red Diamond". Vietnam, June 1970 (Bud Wagner Collection): image by Jerzy Krzeminski, 16 September 2013

M113 acav 1/61st Infantry Division "Red Diamond". Vietnam, June 1970 (Bud Wagner Collection): image by Jerzy Krzeminski, 16 September 2013

M113 acav 1/61st Infantry Division "Red Diamond". Vietnam, June 1970 (Bud Wagner Collection): image by Jerzy Krzeminski, 16 September 2013

M106 mortar track1/61st Infantry Division "Red Diamond". Vietnam, June 1970 (Bud Wagner Collection): image by Jerzy Krzeminski, 16 September 2013

Alpha

4.2 Mounted [M106 mortar track]. I believe that's staff Sergeant Passmore's hind side: photo by David (dvdrhdgkns), c. 1969, posted 8 November 2009

111th ACR, Quan Loi, Vietnam '69-'70: photo by David McSpadden (DandS McSpadden), c. 1969-1970; posted 15 July 2009

111th ACR, Loc Ninh to Fishhook, Vietnam 1969-1970 [M577 command track]: photo by David McSpadden (DandS McSpadden), c. 1969-1970; posted 15 July 2009

Absolutely fascinating and intensely painful to read and look at. I think you've ordered the pictures here extremely well; the top photo is improbably beautiful. I have tried to explain this (meaning the Vietnam War) to Jane, but to the kids I know, it's much more abstract, say, than World War II, which they are made in school to associate with the atomic bomb and Anne Frank. Seeing these photographs reminds me of how when we traveled to China to adopt Jane and looked out from the windows of the airplane, Caroline and I both thought that it looked like classical Chinese landscape paintings. I had always thought of those as highly stylized, rather than realistic, before I saw China. Curtis

ReplyDeleteCurtis, I can't reflect back on that time without a certain sense of regret for everything that was lost in this country, and for this country, in the world, in consequence of that war. For me everything that's happened since has seemed mere aggravation and extenuation.

ReplyDeleteThe kids out there "in country" had no idea what the world was about, and yet the knowledge that then came to them, and through them to those of us as yet out of harm's way, had a tragic quality that should perhaps have served as instruction. But of course their memory has been denied -- it's that war nobody wants to hear about -- some old grizzled guys on the bus still wearing their worn and faded unit caps.

Of course it was "all for nothing", or worse.

"What makes people rebel against suffering is not really suffering itself, but the senselessness of suffering. Man, the most courageous animal, and the most inured to trouble, does not deny suffering per se; he seeks it out, provided that it can be given meaning."

Friedrich Nietzsche: from The Genealogy of Morals

Sometimes I remember and compare conversations I had when I was younger with my friends' parents who were veterans of WW II with those I had with recent Vietnam veterans who were either the brothers of college classmates or other people who unexpectedly mentioned to me their participation in the war when I casually inquired about their lives. Of course, the contexts were different. The WW II veterans had had time to move past their experiences quite a bit; they were in businesses or raising families; they were integrated in society and their experience enfranchised and in a real sense "certified" them. Vietnam was and remains a whole other thing. A few years ago, I was speaking with my then-internist in New York. He's a lovely man, distinguished in his field, and along with his partner, had the reputation of being the most expensive internist in the city. Chatting casually after the check-up, I asked him what he'd been up to since I'd last seen him and he explained that he'd "just come back from Vietnam again" with his wife and daughters. I said "again?" and he explained that he'd served as a physician during the war when he was just out of Yale Medical School. He seemed surprised that I didn't know that medical school graduates whose service had been deferred were then drafted, but he explained the basic story to me, saying essentially, that he'd been mostly assigned to gunboat-on-the-river duty and that, yes, it had been quite a bit like Apocalypse Now -- longish periods of boredom and tedium punctuated by episodes of horror. I'd never seen my doctor look so abstracted, but utterly real and involved in his own life and memories. In our relationship, he was mostly, appropriately, "about me." I think the trip back was therapeutic for him and our conversation taught me a lot and will always stay with me. Another person I know quite well reported an utterly different experience. This man was a senior finance person at one of my companies and, as a young C.P.A., had served in the quartermaster's corps. He said that for him the war had essentially been a quiet, reasonably pleasant (really, he said this) sojourn dispensing payroll. He said that the quartermaster's operation was really the safest place to be and that he would like to be able to speak in a more engaged way and relate possibly more dramatic and interesting stories, but that people really counted on getting paid and they were incredibly insulated in his division. Curtis

ReplyDeleteCurtis, early on in my college-hopping career I landed at one of those Federal Land Grant schools, which had been granted land by the government on condition of supplying officers to the military. It was a smallish all-male school and the ROTC program was compulsory, so that everybody had to serve. That meant not only the never-easy rituals involving drills, inspections, shining and spit polishing, cleaning and learning to fire the weapon and so on, but also quite a lot of classroom work. One signed a contract requiring at least two years' time in the program, so that when I then transferred on to a much larger school, where ROTC was voluntary and the only people in the program were the ones who wanted to be there, I found a different sort of atmosphere. The classroom work continued, there, and got more intense. We mapped and plotted war games. Southeast Asia mostly, but also Suez, Cuba, Central America, anywhere it seemed there might be action. The strategic maps of the world were dense with colored pins indicating the potential hot spots. We moved our units around on the maps and prepared to take up our role in steering the world toward... well, not so much toward anything at all, but specifically against Communism in all its noisome outcroppings around the planet. I suppose the presiding dream was the maintenance of a global "democratic" business alliance in which the world was defined as the constellation of our client states. The officers who taught these classes were all "lifers", all from the South or Southwest, and they would, along with the majority of the "shake and bake" second lieutenants (what we were being groomed for), end up in Vietnam.

ReplyDeleteIn the evolving bloody reality as opposed to the theorizing and gaming and mapping of the war, however, that old-school "old Army" element came to be superseded by another kind of soldier, the grunt whose purpose was simply to stay alive. In order to do that, he would readily roll a grenade into the tent of one of those gung-ho young junior lieutenants, should that officer have been foolish enough to aggressively lead his unit into combat. So there was then the war at the front against the mostly-invisible and extremely clever enemy, and the war at the back against the command structure -- not to mention the various internecine race wars among the troops. All of that pretty much destroyed the American military as a fighting unit. From that horrendous experience came the negative knowledge that Americans cannot do close engagement, particularly as it's always in the streets and jungles and waste lands of somebody else's country, far from home. By late on in the Vietnam war, there were many GIs whose principal motive was escape. They were bad at fighting, and when they came home, they proved very bad at living, "back in the world". It was a lost generation in any useful meaning of the term. The country picked up and started again where it had left off, but things were not the same, and never again would be.

From no previous American war had there emerged heroes like this one.

ReplyDeleteSmall wonder later wars would be fought under much tighter restrictions as to who could say what about what was really going on.

Witnesses.

ReplyDeleteYou want to shove something out into the unknown to preserve your insulation from something you don't understand or want to face.

So you create monsters out of teenage boys--now it's girls too. Great.

And we wonder why these "foreigners" don't jump at the chance to be just like Americans. Jesus.

On 9/11 we came face to face with the same kind of hatred we've been creating all over the world. We didn't like it.

Big surprise.

It was very hard to watch the Hearts and Minds guy; what he said and the way he said it. His delivery was absolutely remarkable. I get lines 1-3 of Curtis F.'s comment, but not lines 3-6. At all (or at least in relation to 9/11). Curtis R.

ReplyDelete