.

Sunset over fertilizer plant near El Centro in the Imperial Valley

Imperial County has ten unincorporated towns the size of Seeley and its

sister community Heber, and 59 other smaller “colonias” or settlements.

Having light posts and a water fountain on the field make it more attractive to kids with little to do in this small community. But these basic amenities only scratch the surface of the problems faced by youth and other residents in Seeley.

Across the street from the local elementary school sits an abandoned house that has come to be known as “the graffiti house.” There, the local mota smokers and mainliners get together and party, leaving beer bottles and even syringes lying on the empty floors. Huge holes have been punched through walls covered in graffiti. Electrical conduits have been pulled out and ripped open, in search of copper wire to sell for scrap.

Being a teenager in Seeley has its dangers. But an even worse one isn't visible at all. It's in the air.

Having light posts and a water fountain on the field make it more attractive to kids with little to do in this small community. But these basic amenities only scratch the surface of the problems faced by youth and other residents in Seeley.

Across the street from the local elementary school sits an abandoned house that has come to be known as “the graffiti house.” There, the local mota smokers and mainliners get together and party, leaving beer bottles and even syringes lying on the empty floors. Huge holes have been punched through walls covered in graffiti. Electrical conduits have been pulled out and ripped open, in search of copper wire to sell for scrap.

Being a teenager in Seeley has its dangers. But an even worse one isn't visible at all. It's in the air.

As Joahn Molena sits in his back yard, hugging his pit bull in front of his henhouse, dust coats everything outside his home. Molena's proud of his white Honda Civic, with its mag wheels. It's a few years old, but still in primo condition. Of course, he has to wash it almost every day because dust in Seeley is everywhere.

It blows in from the fields that surround the unincorporated communities. In Heber, that dust comes from the empty expanses at the edge of town that previously housed corrals for the El Toro Land and Cattle Company. The hooves of the cattle housed there ground animal waste into the earth in those empty lots. Neighbors worry now about what the dust might contain. Manuel Gonzalez (who is retired, but asked that his real name not be used) lives at the end of the street, where it meets the field. "Every day my wife vacuums up the dust in the house, but an hour later it's back."

And just across Fawcett Road are El Toro's current feedlots. Hundreds, even thousands of cattle are housed in dense pens, eating their way to eventual slaughter. In the furnace-like heat of the Imperial Valley summer, the smell of cattle waste wafts across the town, giving neighbors a good idea of what the dust is made of. So many feedlots cover the valley that the smell gets to Seeley as well.

Other air pollutants also come with the industrial agriculture that has dominated the Imperial Valley since the All-American Canal, and the Alamo Canal before it, brought Colorado River water to the desert in 1900. Seeley and Heber themselves were the products of the land boom that followed. The post office in Seeley, named for developer Henry Seeley, opened in 1909. Heber is even older, and was founded by the Imperial Valley Land Company in 1903, and named for developer A.H. Heber.

Today, the land surrounding the two towns is farmed in huge tracts of hundreds of acres. To make the desert productive, ranchers not only built the world's largest irrigation canal, but also developed farming methods dependent on chemical fertilizers and strong pesticides. Even with the recent advance of some large-scale organic operations, it's still common to drive a local highway and see a small airplane called a cropduster make circular swoops and passes over the green crops. From the nozzles on its wings, a fine spray of pesticide coats the leaves below. Air moves, however, and with it, the chemical spray from the plane -- what's called pesticide drift.

Communities like Seeley and Heber, located in the middle of the fields, can get that drift, even diluted by breezes and wind.

In other fields, tractors pull a rig with tanks of chemicals, and spray nozzles that release them just inches from the plants. Less drift, perhaps, but after many years, powerful pesticides and fertilizers are omnipresent, not just in the fields, but in the small communities they surround as well.

Then, when the crops are in, Imperial Valley farmers are notorious for burning. Big mowers cut and collect the stalks left from crops after they're harvested. Piles of dry plants are then set alight next to local fields and highways. The smoke is often so intense that roads are blocked to traffic, or at least they're supposed to be.

Imperial Valley Residents Must Fight for Right to Breathe Clean Air: David Bacon, New America Media, 3 March 2012

On state highway near Plaster City, California. The white dust is from a gypsum plant.

Gypsum plant at Plaster City, California. White dust from the plant is part of the atmosphere

.

Moving cattle raise dust along the highway -- near Calpatria in the Imperial Valley

Dry heat and high winds equal eye-stinging, nose itching dust storm, Imperial Valley

.

Moving cattle raise dust along the highway -- near Calpatria in the Imperial Valley

Dry heat and high winds equal eye-stinging, nose itching dust storm, Imperial Valley

Spraying fertilizer near El Centro, California

Fertilizing, Imperial Valley

Fertilizing fields, Imperial Valley

Fertilizing, Imperial Valley

Fertilizing near El Centro, California

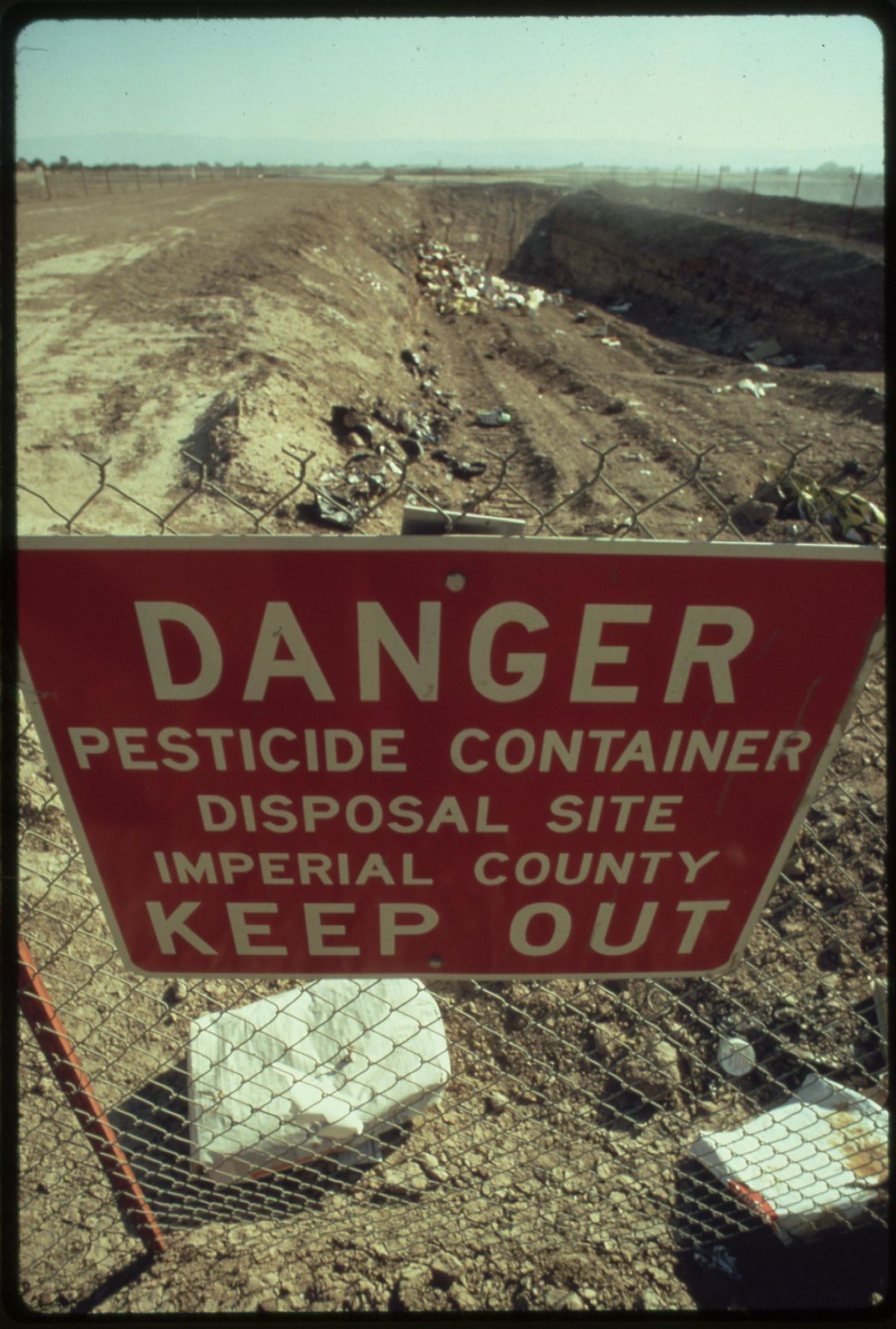

Special precautions must be taken for disposing of hazardous materials, as in this area near El Centro in the Imperial Valley

Farmland of the Imperial Valley, and the Salton Sea (infrared film)

Pickers in field near El Centro, California

Irrigated field in the Imperial Valley

Irrigated fields of the Imperial Valley

Cracked earth -- a result of irrigation and intense dry heat

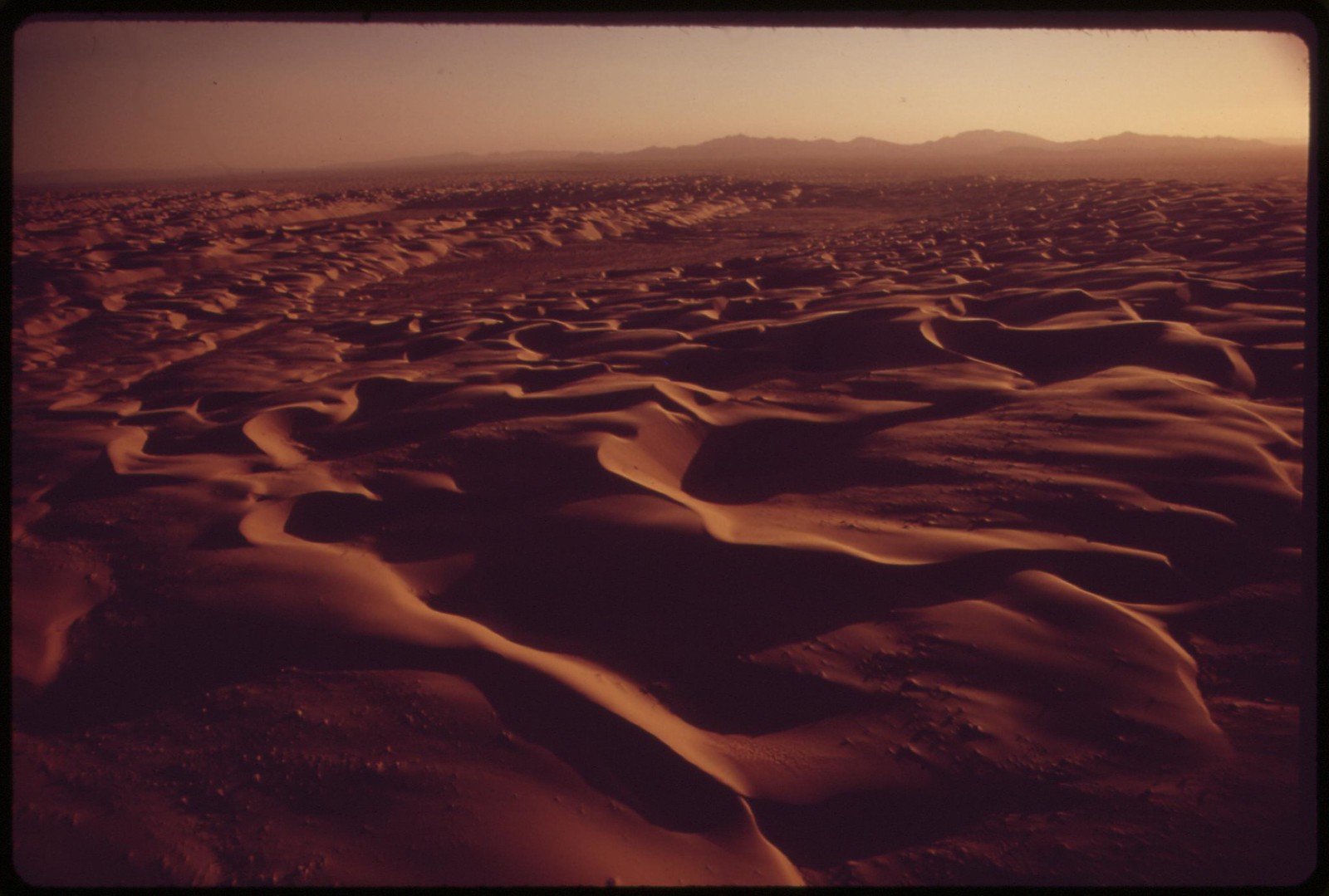

Sand dunes in the western part of the Imperial Valley

A hundred-mile ribbon of sand dunes separates the Chocolate Mountains of southern California from the Imperial Valley, which stretches from the Salton Sea into Mexico

Parker Dam on the Colorado River forms the eastern end of the 150-mile metropolitan aqueduct which supplies drinking water to Los Angeles and intermediate cities

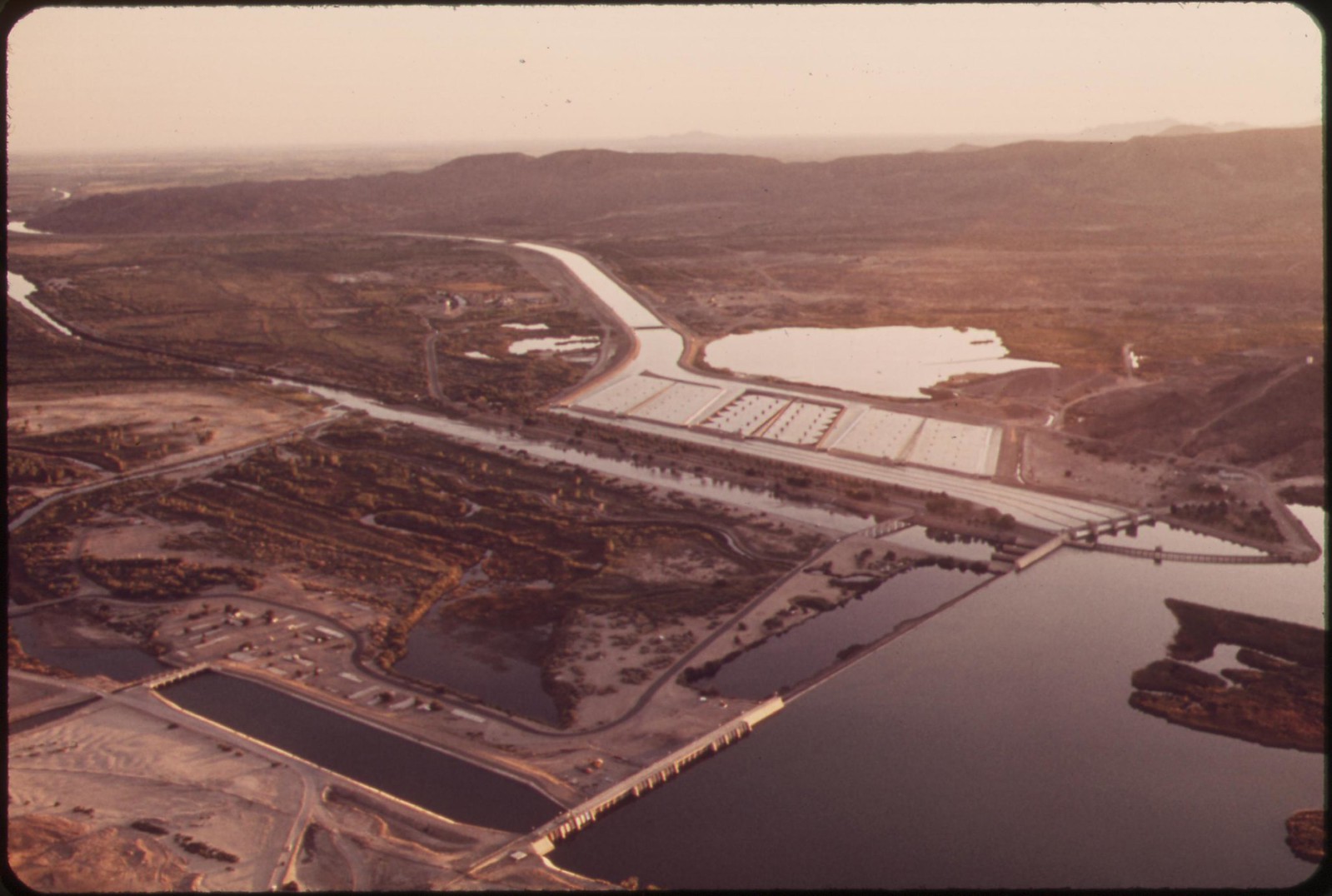

The All-American Canal transformed the Imperial Valley from desert to farm land with water from the Colorado River

The Colorado River feeds crops and irrigation (dark areas). Town of Needles, California in foreground.

The All-American Canal feeding the thirsty Imperial Valley. Mexico on the left.

Imperial Dam takes last of Colorado River water for the United States. It diverts water into All-American Canal. Desilting basins in center background.

Shrunken Colorado River winds between onetime flood banks. This is all that's left after Imperial Dam (background) has diverted four-fifths of the river into the All-American Canal.

Colorado River at the Mexican border, Yuma County, Arizona

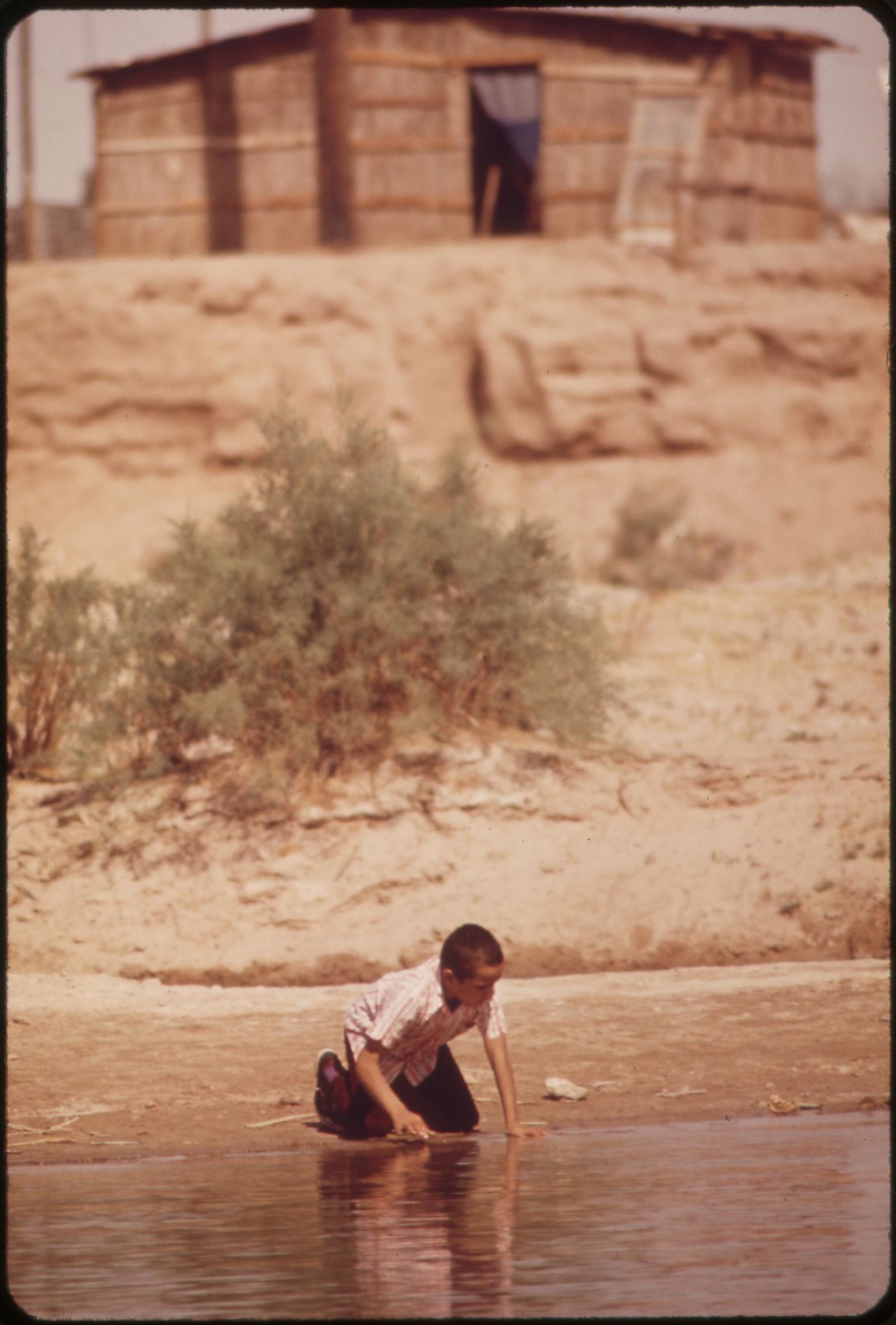

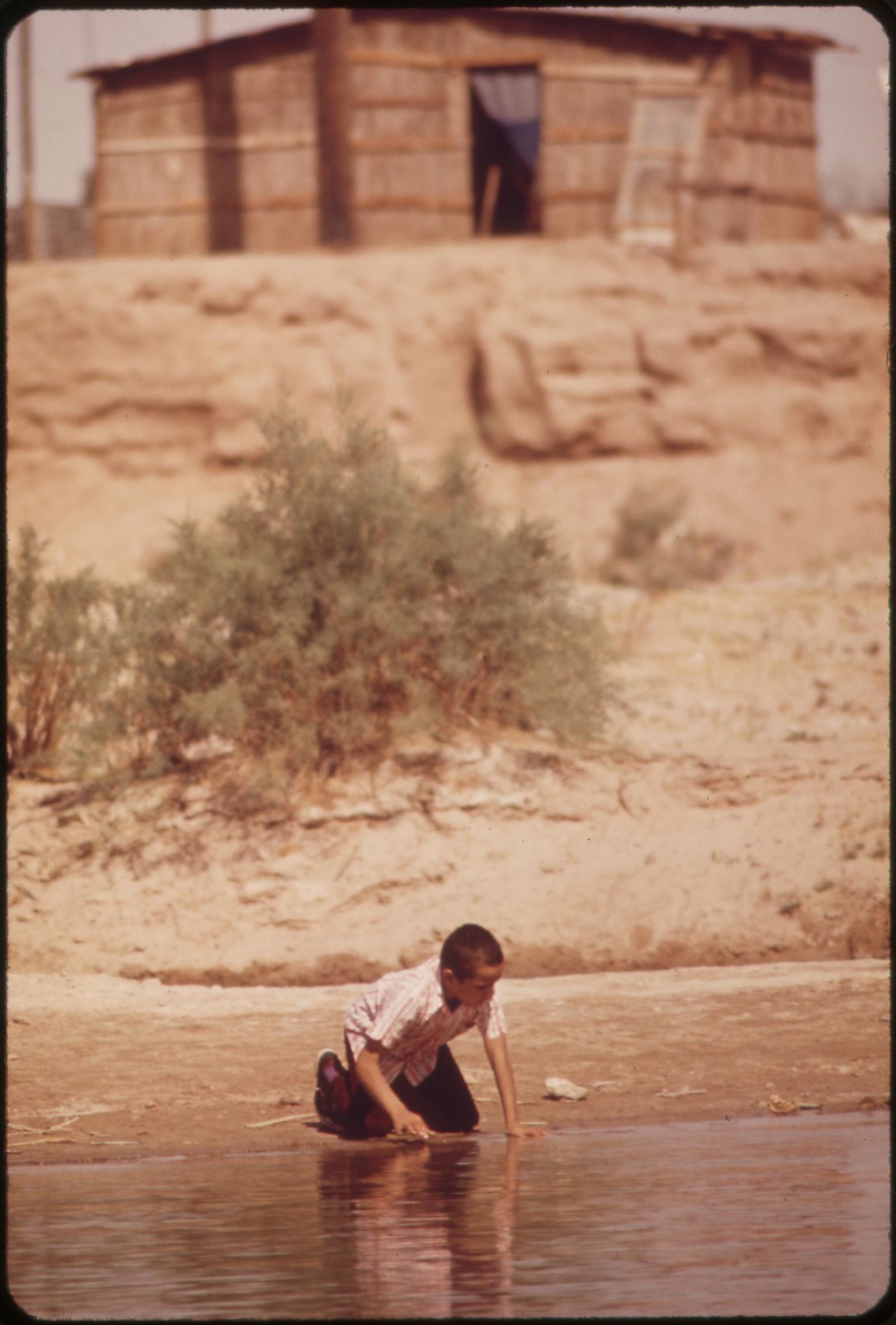

Colorado River on the Mexican side of the border

Colorado River on the Mexican side of the border

Colorado River on the Mexican side of the border

Colorado River on the Mexican side of the border

Las Vegas street scene

Night lights, Las Vegas

Night lights, Las Vegas

Las Vegas shopping center

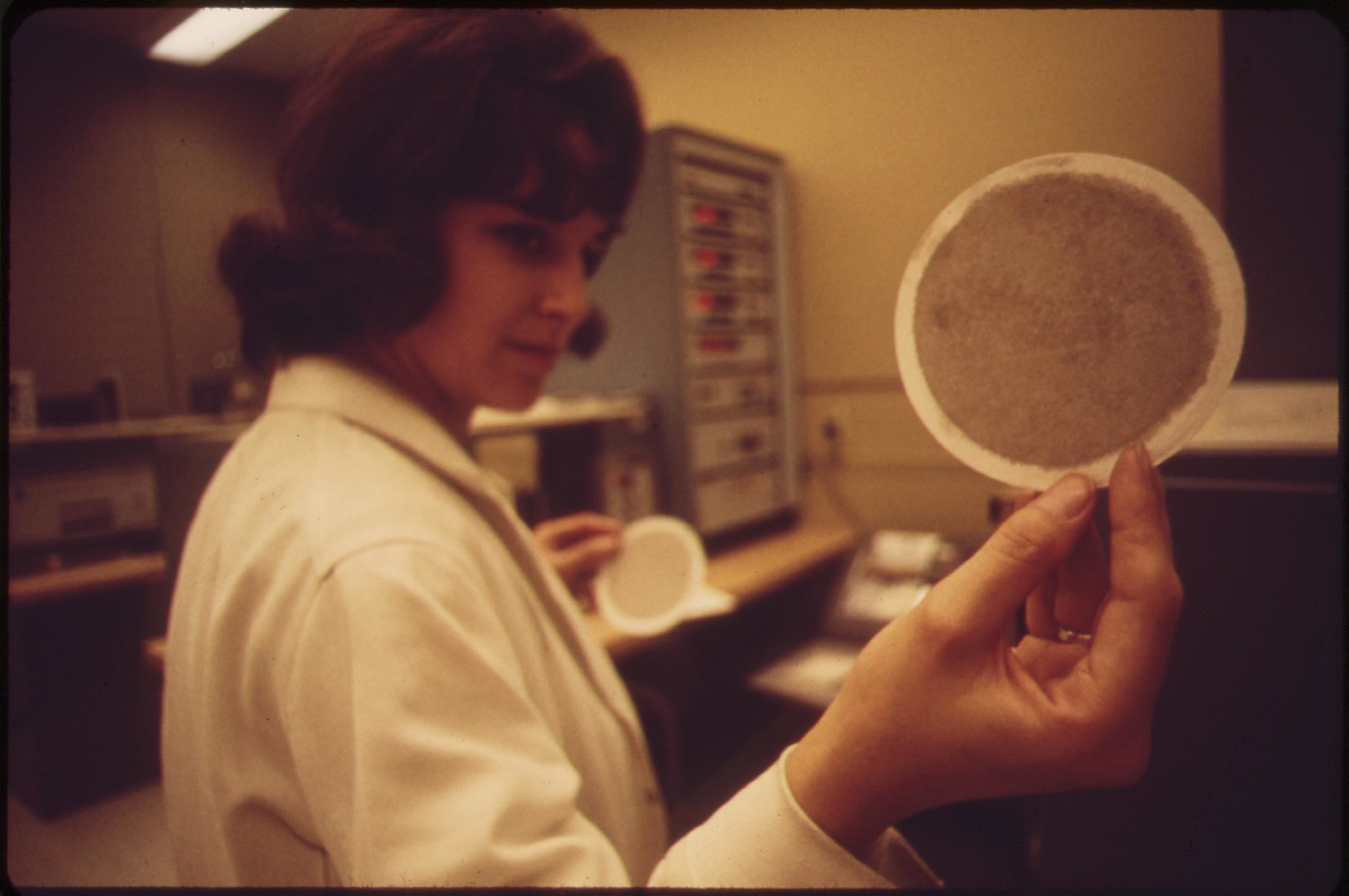

Laboratory technician at EPA's Las Vegas National Research Center holds up an air filter

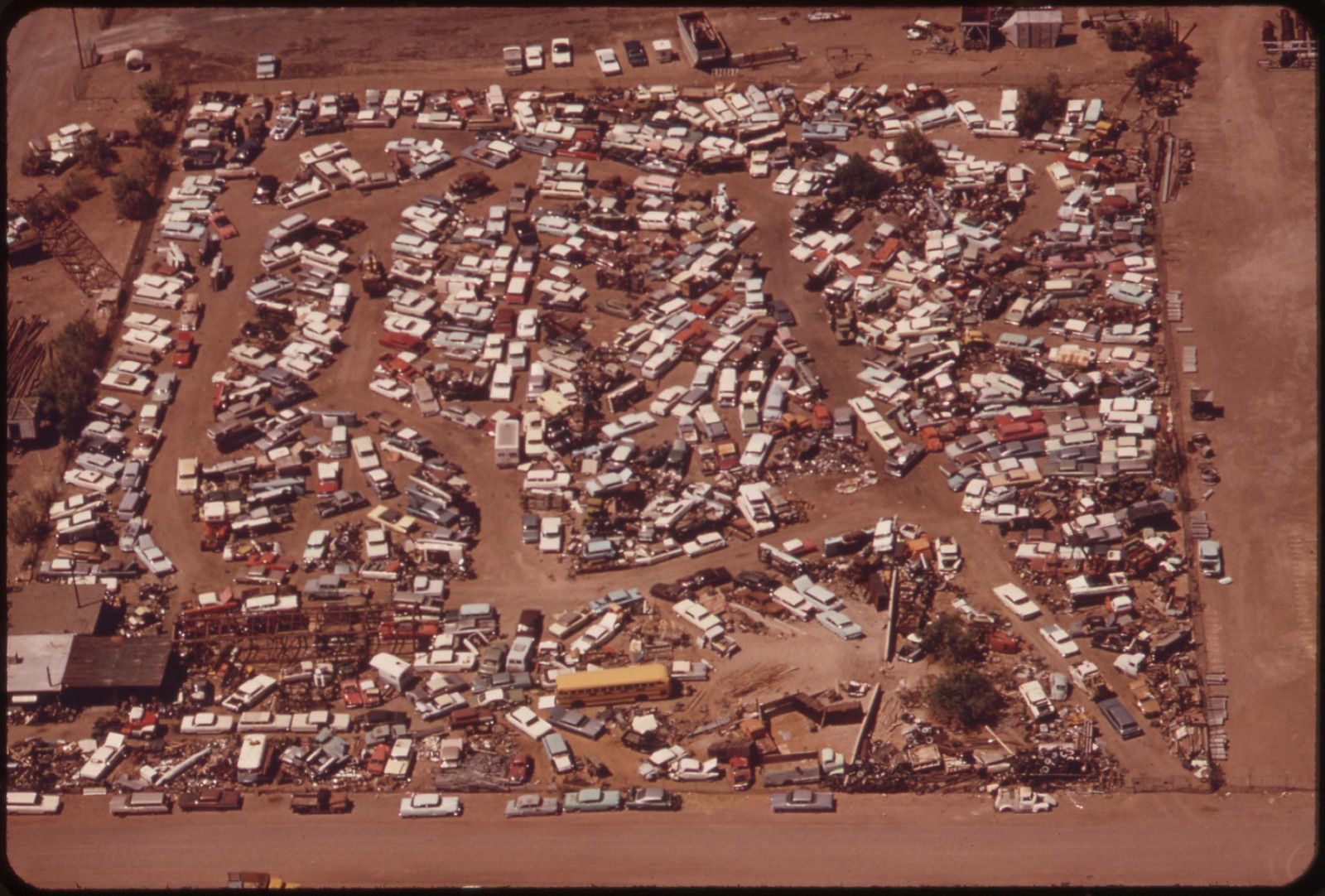

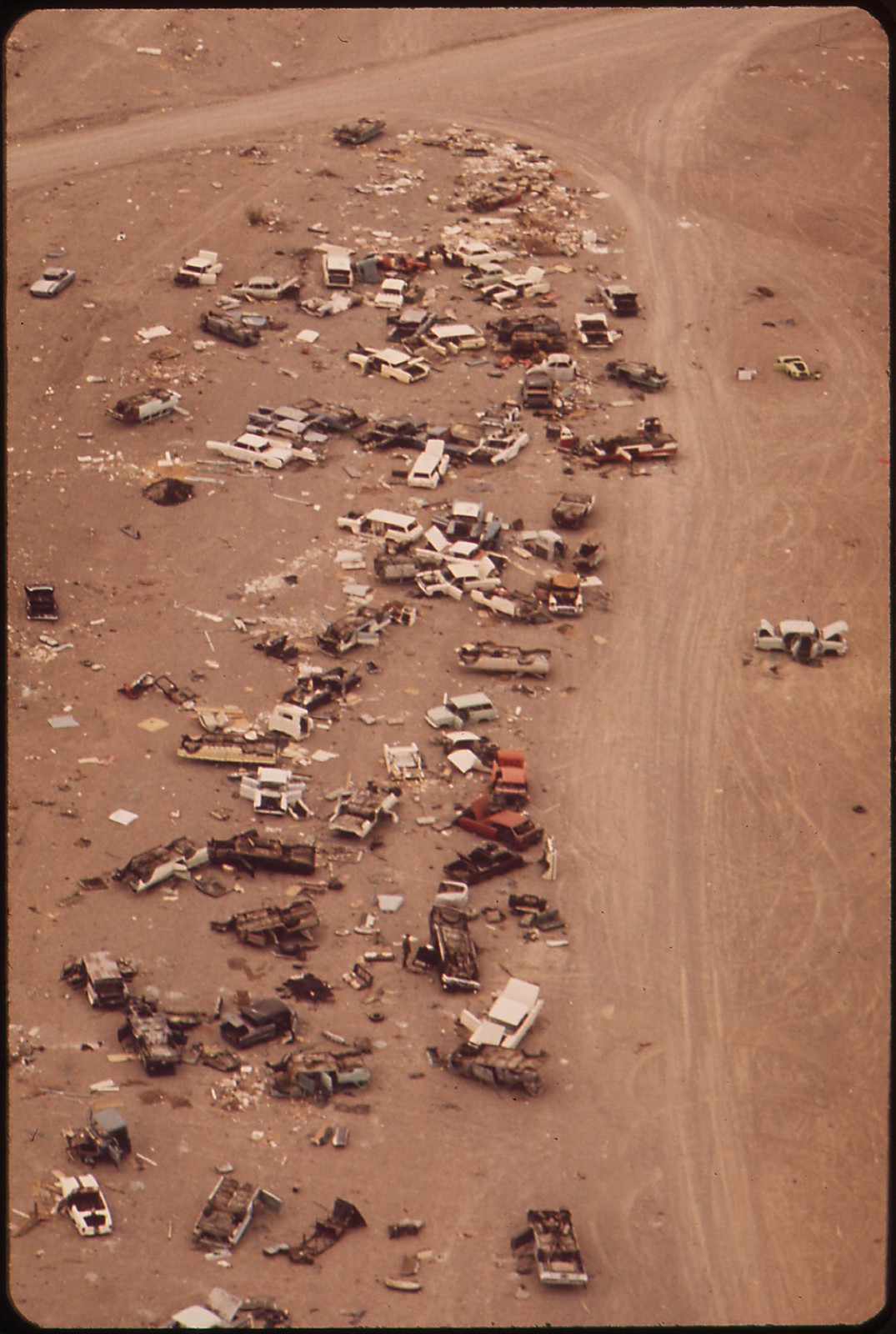

Auto dump, Henderson, Nevada

Funeral home, Henderson, Nevada

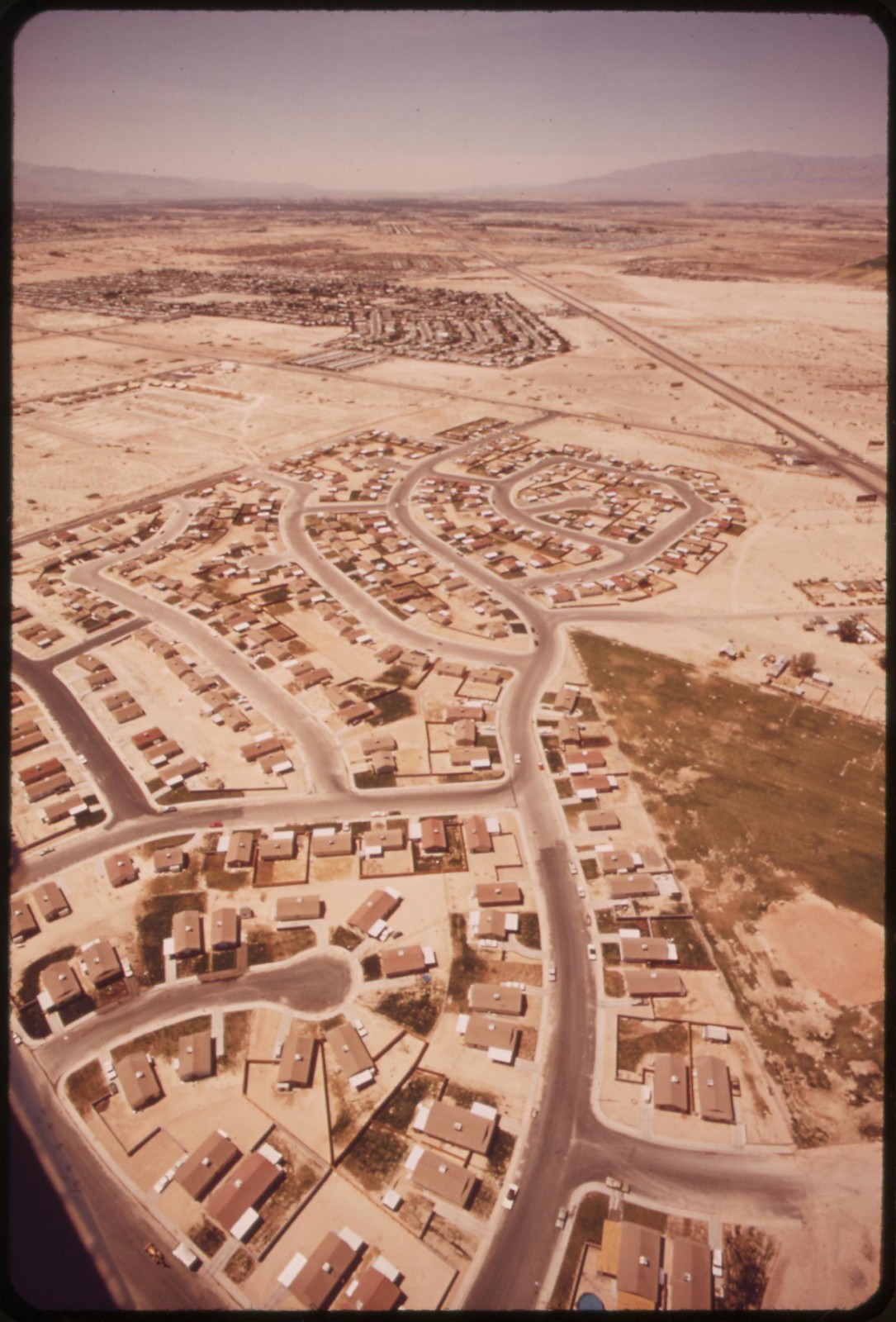

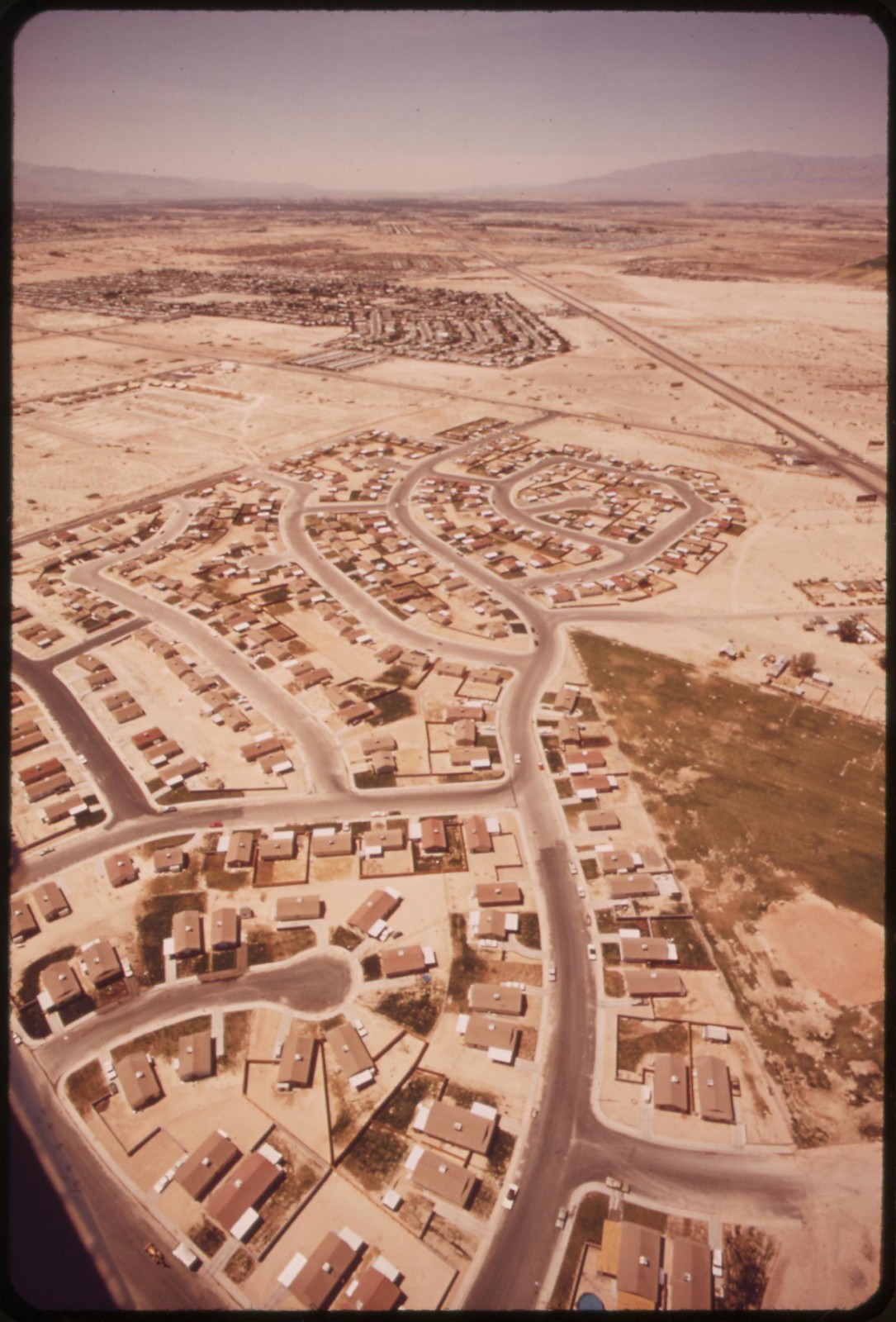

Desert real estate

Housing, Lake Havasu City, Arizona

Housing, Lake Havasu City

Housing, Lake Havasu City

London Bridge crosses Havasu Lake at Lake Havasu City, Yuma County, Arizona. Rescued from demolition by an American buyer, the famous old span was transplanted here in 1971.

London Bridge, transplanted here in 1971, crosses arm of Havasu Lake, which is fed by the Colorado River, Yuma County, Arizona

American Egrets roosting and nesting on the Colorado River Indian Reservation near Parker, Yuma County, Arizona

Marshland and migratory birds at Lake Havasu National Wildlife Refuge, which is about equally divided between California and Arizona. The lake is fed by the Colorado River.

Marshland fowl at Salton Sea National Wildlife Refuge

This entire field of straw west of El Centro in the Imperial Valley, burned off in less than half an hour. Smoke was visible for 20 miles. Owner wished to clear field quickly for planting another crop.

Photos by Charles O'Rear for the Environmental Protection Agency's Project DOCUMERICA, May 1972 (US National Archives)

It feels strange and awkward to say this, but some of these are about the most beautiful color photographs I've ever seen. I think it's the way they remind me of my first trips on airplanes, not being able almost to believe what I was seeing. Curtis

ReplyDeleteFollowers of this site will recall a post from a year and a half ago in which we saw a similar long-view photographic method employed to survey the transformation of the California coastline.

ReplyDeleteCharles O'Rear: California Coastal Development: The Creeping Advance

These photo surveys were made at a critical time, when man-made changes in the land and landscape were determining a new course of history for the West.

At that time, Chuck O'Rear commented:

"Nice to see my photos after near 40 years. This is the first effort I've seen to describe in photos the California coast problems."

I think he's right about that, and that his coastal survey remains the most authoritative and informative picture of a sweeping process of change.

The same can certainly said for this "big picture" of development in the Colorado River watershed and the Imperial Valley.

Thanks Curtis, hadn't seen that till just now.

ReplyDeleteI know what you mean about this --

"I think it's the way they remind me of my first trips on airplanes, not being able almost to believe what I was seeing."

With some things, especially big things, distance may be essential to any kind of accurate view.

This survey seems particularly relevant now, when the long-worried issues relating to water -- who owns it, and how it shall be used -- are more pertinent than ever out here, in what was once and bodes to be again a great desert.

(And yes, I'd certainly agree that, if we were somehow able to detach the historical meaning of what we are seeing from the immmediate visual experience, many of these aerial shots would definitely qualify as great works of "abstract" art.)

Mind-boggling frenzy of self-destruction.

ReplyDeleteRed,

ReplyDeleteYes, and if that sounds bad, just imagine how the equation has looked from the Mexican side of the border...

These images tear at the heart; they provoke a subtle state of alarm because of what they signify. Their beauty seems almost beside the point.

ReplyDeleteThe Imperial Valley: we can be sure that it wasn’t indigenous people who fastened that name to a segment of the planet. Nomenclature reflects the problem; it's something we use to blind ourselves.

Hazen, yes, the irrelevance of the anomalous beauty -- that's what I meant by "...if we were somehow able to detach the historical meaning of what we are seeing from the immediate visual experience..." Such detachment would probably require that we be watching from another planet, one on which the fate of the Earth didn't matter in the slightest to whatever intelligence is doing the watching.

ReplyDeleteTrouble is, we're limited to the view from and on this one -- which is getting uglier by the minute.

"The Imperial Valley: we can be sure that it wasn’t indigenous people who fastened that name to a segment of the planet. Nomenclature reflects the problem; it's something we use to blind ourselves."

Exactly. Imperial Valley. All-American Canal. The death of a part of the earth, calculated in detail, over a period of time, for short-term profit ... all reflected in the deceptions built into the nomenclature.

The regularity of the boundaries is the thing that makes me shiver.

ReplyDeleteI remember being taken to visit the reservoir in Bala by my father and him telling me of the ruins of villages beneath.

So sad, all of it. From the small to the large. Water, the issues are everywhere, even where it rains nonstop. Our river here that I walk by is completely devoid of life this spring. Last year, there were something like ninety plus nesting herons. I have seen a few herons walking in the water, looking down at the clear and lifeless water . . .

ReplyDeleteNin,

ReplyDeleteThe best indication of the water situation is always the response of the animals. Nobody includes them in the contracts, compacts, projects and arrangements. This year the deer coming down out of the hills into the city streets have become bolder than ever. That's because it's so dry. After being run over in the street I myself have had a hard time making it up the steep unstable steps, but to the deer a mere hillside is no problem; it's take the risk or die. They are here all the time now, browsing. In fact, today, within a few hours, there was first a violent car crash right out front here on the freeway feeder, totalling three cars... and then, once the tow trucks had hauled away the wreckage, the deer were back, prancing down the same lethal stretch of speedway with ears pinned back, sniffing the exhaust fumes.

Yesterday the temperature in El Centro in the Imperial Valley reached 107 degrees F.

Not all that unusual.

My first visit to the Imperial Valley came in 1951, riding through the desert in the back seat of an old De Soto. The dry heat seemed vaguely unreal. A shimmering haze rising from the parched bare ground. We pulled in at a roadside joint, mainly for the shade. The next mistake was swallowing some desert roadhouse barbeque.

Up to that time I had thought of California much as a million other fools had done -- as a paradise.

Now we're told to expect a "super El Niño" in this coming winter.

WB,

ReplyDeleteHuw makes us feel the plight of the drowned village of Capel Celyn in that curious way some songs have of being moving though you can't make out a bloody word of what they're actually saying. Some of the commenters seemed to be understanding it well enough, though I could not make out a bloody word of what they're saying -- except the one commenter who laments that when Huw visited Bala youth camp in 1970 he declined to sing this song, on grounds it needed "a gitar mawr". And of course there's that one kindly Anglophonic commenter Alan Hughes, who approves the instrumentation just as is -- "bongos gret!" But a bit of further digging helped to clarify matters. "Dŵr", I now have learned, means Water. And as Huw himself has explained the song, it "describes the feelings of a Welshman returning to the valley where he was reared only to find his people had been expelled and the valley flooded to make a reservoir to supply water to English cities".

Fair enough I say. The English be damned!

And as to the regularity of the boundaries -- in this country, simple rectilinear property lines have always seemed the best way to divide up into owned bits all that nobody can ever really own without the imposition of force.

ReplyDeleteThe Colorado rises in the Never Summer Mountains of Wyoming. Once upon a time this great river drained into the Gulf of California. No more. As it runs along, it is drained down to a trickle in a series of "diversionary projects" -- places that rob the river along its way. There has always been great competition for rights and contracts, compacts and the like. But now as the climate of the region has changed along with the increase of demand upon the river system, the question arises, not so much will the water hold out, as when will the water run out.

Because out this way, as Marc Reisner wrote in 1986 in Cadillac Desert: The American West and its Disappearing Water, there's still

"a lot of emptiness amid a civilization whose success was achieved on the pretension that natural obstacles do not exist... Thanks to irrigation, thanks to the Bureau [of Reclamation]... states such as California, Arizona, and Idaho became populous and wealthy; millions settled in regions where nature, left alone, would have countenanced thousands at best... what has it all amounted to?... not all that much. Most of the West is still untrammeled, unirrigated, depopulated in the extreme... Westerners call what they have established out here a civilization, but it would be more accurate to call it a beachhead. And if history is any guide, the odds that we can sustain it would have to be regarded as low.

.

"Were it not for a century and a half of messianic effort toward [manipulation of water], the West as we know it would not exist... Confronted by the desert, the first thing Americans want to do is change it. People say that they 'love' the desert, but few of them love it enough to live there... Most people 'love' the desert by driving through it in air-conditioned cars, 'experiencing' its grandeur. That may be some kind of experience, but it is living in a fool's paradise. To really experience the desert you have to march right into its white bowl of sky and shape-contorting heat with your mind on your canteen as if it were your last gallon of gas and you were being chased by a carload of escaped murderers... One does not really conquer a place like this. One inhabits it like an occupying army and makes, at best, an uneasy truce with it.

.

"The whole state thrives, even survives, by moving water from where it is, and presumably isn't needed, to where it isn't, and presumably is needed. No other state has done as much to fructify its deserts, make over its flora and fauna, and rearrange the hydrology God gave it. No other place has put as many people where they probably have no business being. There is no place like it anywhere on earth. Thirty-one million people (more than the population of Canada), an economy richer than all but seven nations' in the world, one third of the table food grown in the United States---and none of it remotely conceivable within the preexisting natural order".

You might find William Vollmann's Imperial of interest. It's massive, but worth the read. http://nymag.com/arts/books/reviews/58062/

ReplyDeleteEvery image, every word in this post is an education. Thank you Tom. And there's a thesis to be written on how birds figure in BTP. These have a great silent power - witnesses, chorus, victims, survivors (just, maybe).

ReplyDelete