Szerb-horvát szájkarate, rekordszámú menekült, drótakadály a szlovén határon: image via Index,hu @indexhu, 25 September 2015

Attila József: Lullaby

The sky has shut its eyes of blue,the house has shut its many eyes,

the meadow sleeps with quilt up too –-

sleep nice now, sleep, little Balázs.

Flies and wasps have gone to sleep,

on every foot a bowed head lies,

there's not a buzz or hum to seek –-

sleep nice now, sleep, little Balázs.

The tramcar has dozed off as well

-– and without its rattle and clash –-

it dreams it dares to clang its bell –-

sleep nice now, sleep, little Balázs.

The coat is sleeping on the chair,

its tear takes forty winks, quite wise,

today it won't split further there –-

sleep nice now, sleep, little Balázs.

Ball and whistle close their eyes,

wood and woodland outing hush,

and the good sweet gives sleepy sighs –-

sleep nice now, sleep, little Balázs.

You'll reach the far-off, you'll go on

like a glass marble in a flash –-

be a giant, only with eyelids down -–

sleep nice now, sleep, little Balázs.

You'll be a fireman and a soldier!

A shepherd's ear for wild beasts' dash!

Look, mother's nodding, going over –-

sleep nice now, sleep, little Balázs.

Attila József (1905-1937), Lullaby (Altató), 1935, translated from the Hungarian by Edwin Morgan in From Attila József: Sixty Poems (Mariscat, 2001

A migrant boy looks out from a field near the Hungarian border at Röszke: photo via Budapest Telegraph, 24 August 2015

Jozsef Attila: Altató

Lehunyja kék szemét az ég,

lehunyja sok szemét a ház,

dunna alatt alszik a rét --

aludj el szépen, kis Balázs.

Lábára lehajtja fejét,

alszik a bogár, a darázs,

velealszik a zümmögés --

aludj el szépen, kis Balázs.

A villamos is aluszik,

-- s mig szendereg a robogás --

álmában csönget egy picit --

aludj el szépen, kis Balázs.

Alszik a széken a kabát,

szunnyadozik a szakadás,

máma már nem hasad tovább --

aludj el szépen, kis Balázs.

Szundít a labda, meg a sip,

az erdő, a kirándulás,

a jó cukor is aluszik --

aludj el szépen, kis Balázs.

A távolságot, mint üveg

golyót, megkapod, óriás

leszel, csak hunyd le kis szemed, --

aludj el szépen, kis Balázs.

Tüzoltó leszel s katona!

Vadakat terelő juhász!

Látod, elalszik anyuka.

Aludj el szépen, kis Balázs.

lehunyja sok szemét a ház,

dunna alatt alszik a rét --

aludj el szépen, kis Balázs.

Lábára lehajtja fejét,

alszik a bogár, a darázs,

velealszik a zümmögés --

aludj el szépen, kis Balázs.

A villamos is aluszik,

-- s mig szendereg a robogás --

álmában csönget egy picit --

aludj el szépen, kis Balázs.

Alszik a széken a kabát,

szunnyadozik a szakadás,

máma már nem hasad tovább --

aludj el szépen, kis Balázs.

Szundít a labda, meg a sip,

az erdő, a kirándulás,

a jó cukor is aluszik --

aludj el szépen, kis Balázs.

A távolságot, mint üveg

golyót, megkapod, óriás

leszel, csak hunyd le kis szemed, --

aludj el szépen, kis Balázs.

Tüzoltó leszel s katona!

Vadakat terelő juhász!

Látod, elalszik anyuka.

Aludj el szépen, kis Balázs.

1935. febr. 2.

Szijjártó a BBC-n ostorozta a médiát [photo Reuters]: image via Index,hu @indexhu, 25 September 2015

Bus collides with tram in the rain, Budapest: photo by Gábor Olvasónk vua index,hu, 25 September 2015

Situation worsens on the serb-cro border as heavy rain approaches - #refugeecrisis: image via Levente Hernadi @Lvnte, 25 September 2015

Record 10,000 migrants enter Hungary on Wednesday: AFP, 24 September 2015

A new record of 10,046 migrants entered Hungary on Wednesday, mostly via Croatia, police say.

A

total of 9,939 migrants entered from Croatia, while 102 crossed from

Serbia, police said. The discrepancy of five migrants in the figures was

not immediately explained.

The previous record was set on

September 14, when 9,380 migrants crossed just before Hungary

effectively sealed its border with Serbia.

The closure of

Hungary's border with Serbia last week led thousands of migrants to

enter Croatia, quickly overwhelming authorities who then started bussing

them to the Hungarian border.

After crossing into Hungary, trains

then take the migrants to the Austrian border. The eastern Austria

state of Burgenland recorded 5,900 new arrivals on Wednesday and a

further 2,200 since midnight.

From Austria the

migrants seek to travel onwards to northern Europe, in particular Sweden

and Germany which has relaxed asylum rules for Syrians but also

tightened border controls.

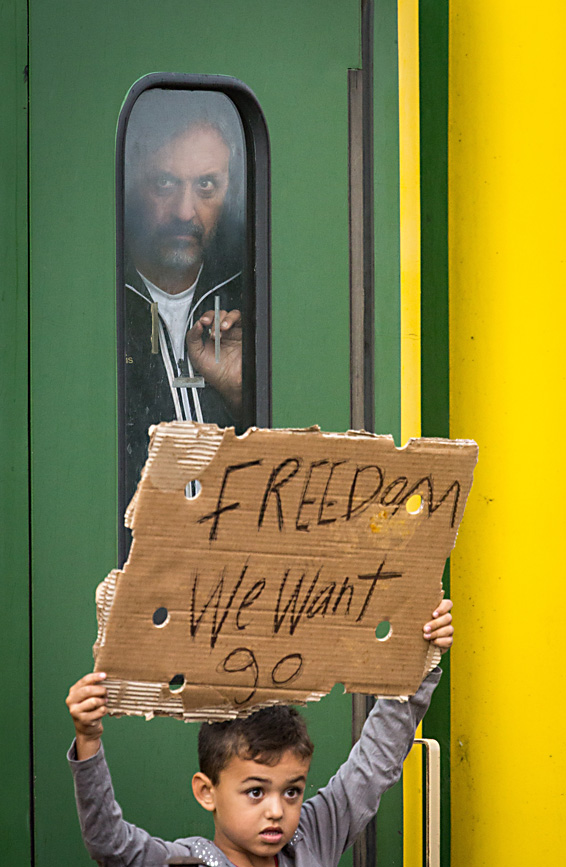

Migrants protest outside a train that they are refusing to leave for fear of being taken to a refugee camp from the train which has been held at Bicske station since yesterday in Bicske, near Budapest, Hungary. According to the Hungarian authorities a record number of migrants from many parts of the Middle East, Africa and Asia are crossing the border from Serbia. Since the beginning of 2015 the number of migrants using the so-called Balkans route has exploded with migrants arriving in Greece from Turkey and then travelling on through Macedonia and Serbia before entering the EU via Hungary. The massive increase, said to be the largest migration of people since World War II, led Hungarian Prime Minister Victor Orban to order Hungary’s army to build a steel and barbed wire security barrier along its entire border with Serbia, after more than 100,000 asylum seekers from a variety of countries and war zones entered the country so far this year: photo by Matt Cardy via FT Photo Diary, 4 September 2015

Istvan Rev: Hungary’s Politics of Hate

Hundreds of #refugees camp inside a cemetery at Sid (cro) waiting for bussesWe found the new #Madmaxwagon, built for the CRO-HUN border #Zakany #Hungary #refugeecrisis: image via Levente Hernadi @Lvnte, 23 September 2015

Hungary’s Politics of Hate: Istvan Rev, International New York Times, 25 September 2015

BUDAPEST — While journalists flocked to cover the chaos at Budapest’s Keleti Station and thousands of refugees marched on foot

along the M1 motorway toward the Austrian border, Viktor Orban, the

prime minister of Hungary, was watching the Hungary-Romania soccer match

from his V.I.P. box in the Budapest football stadium.

Before

the kickoff, Hungarian and Romanian “ultras” shouted Nazi slogans and

fought one another at the stadium, after having warmed up by harassing,

insulting and beating up hundreds of hopelessly exhausted refugees, who,

in their panic, had mistaken the noise of fireworks for gunshots.

Mr.

Orban, who recently built a $20 million dollar soccer stadium next door

to his summer cottage -- with seats for 4,000 people in a village with

fewer than 2,000 inhabitants -- had cut short a meeting with foreign

leaders in Prague in order to get back to Budapest in time for the

match. His behavior recalled the habit of Nicolae Ceausescu, the

one-time Romanian Communist dictator, who never allowed social unrest to

disturb his favorite pastime.

What

is happening in Hungary is not just about the global refugee crisis and

its consequences for Europe. It is also the beginning of the 2018

Hungarian election campaign. And it provides a cautionary tale about

what could happen in Europe, and not only in Europe, when radical,

nationalist populists take over the state.

Mr.

Orban recently announced in the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung that his

aim is “to keep Europe Christian.” He began his xenophobic campaign

eight months ago in Paris after the Charlie Hebdo massacre. He chose the

massive demonstration in Paris on Jan. 11 as the most appropriate

occasion to announce the need to stop the influx of non-Christian

migrants to Europe.

#Hungary President #Orban's anti-terror-unit captured "terrorists": image via Mark @markito0171, 18 September 2015

For

him the massacre demonstrated that migration inevitably leads to terror

-- despite the fact that the killers were not recent immigrants but

long-settled French citizens. He insists that European political

correctness and decadent moral relativism make it impossible to address

this threat.

At

the end of this unusually hot and tragic summer, he announced: “We are

experiencing the end of a spiritual-intellectual era. The era of

liberalism.” But this, Mr. Orban declared, “provides the opportunity for

the national-Christian thinking to regain its dominance not only in

Hungary, but in the whole of Europe.” To defend European Christendom,

Hungary -- together with the Czech Republic, Slovakia and Romania -- voted

last week against distributing 120,000 mostly Muslim asylum seekers

among the European Union’s member states. Never mind that the Hungarian

minister of the interior announced in January 2014 that Hungary would be

easily capable of accommodating 170,000 Hungarian-speaking Ukrainians,

who are predominantly Christians, if they ever had to flee.

In

early 2015, the popularity of the ruling party declined dramatically

due to major corruption scandals involving the government and Mr.

Orban’s family. Voters started shifting toward the neo-Nazi Jobbik party

-- which is, distressingly, the only serious opposition to Mr. Orban’s

government. These neo-Nazis have been moralizing about anticorruption

policies and defending the rights and interests of what they call

true-born Hungarians.

Raising

the refugee issue provided Mr. Orban’s beleaguered government with a

unique opportunity to mount a nationalist, racist, xenophobic campaign

of its own -- while of course taking care to distinguish itself from the

neo-Nazis by refusing to spout hatred about either the Jews or the Roma.

Another fence is being built on the #Hungary-an-#Slovenia-n border. The #Croatia-n one will be finished in the weekend: image via Szabolics Panyi @panyiszabolics, 24 September 2015

Following

a nationwide billboard campaign over the summer that incited hatred and

spread fear with slogans like “If you come to Hungary, you must respect

our culture,” the country -- as if it were at war -- is now flooded with

huge posters: “The people decided, we must defend our country.” Faced

with Mr. Orban’s radicalism, the neo-Nazis look faint-hearted and

indecisive. Had Jobbik done what the prime minister is doing now, it

would have been widely denounced. But the prime minister is posing as

the Christian savior of Europe.

OH, FUCK OFF HUNGARY. Taking a full page refugee warning in a Jordanian newspaper #NoOneIsIllegal #FortessEurope: image via Tarakiyee @Tarakiyee, 11 September 2015

According

to the official history books -- and there are only officially-approved

history books in Hungarian schools today -- Hungary has always been the

last bastion of Christianity in Europe: against the Mongols in the 13th

century, against the Ottomans in the 16th and 17th, and against the

Bolsheviks during World War II.

Now,

according to this narrative, Hungary is being forced to defend the same

values as the West lapses into moral relativism, multiculturalism and

same-sex marriage. Sometimes, according to the logic of Hungarian

foreign policy, the only way to defend the traditions of Christianity is

to make an alliance with the East, joining Vladimir Putin’s crusade

against the decadent West.

Murio la verdad: Francisco de Goya y Lucientes, 1810-1814, etching, 175 x 220 mm

Murio la verdad: Francisco de Goya y Lucientes, 1810-1814, etching, 175 x 220 mm

The

country’s top Catholic clergy is doing its part to arouse enmity, too.

Cardinal Peter Erdo, who is also president of the Council of European

Bishops, said that if the church provided asylum to the refugees, it

would amount to becoming people-smugglers. The bishop of Szeged, Laszlo

Kiss-Rigo, responded to Pope Francis’ plea to show mercy to the refugees

by asserting: “The pope does not know what he says.” The church and

government seem to have forgotten the hospitality Hungarian refugees

experienced in the West when they fled after the Soviets crushed the

1956 revolution.

Hungary

has already built a razor-wire fence along the Serbian border; it is

now constructing another along the frontier with Croatia. Relations with

neighboring countries haven’t been worse since the dissolution of the

Austro-Hungarian monarchy in 1918. A new law passed by the ruling party

with neo-Nazi support authorizes the government to introduce a state of

emergency, mobilize military reservists, and treat illegal border

crossing as a crime punishable by several years in prison.

Mr.

Orban is bolstering his popularity by spreading fear and inciting

hatred — not only against refugees, but against the thousands of

Hungarians who have helped them day and night, in heat and rain. The

country has turned into a fenced fortress that imagines it is fighting

an enemy at the gates, and also an enemy within: the good-hearted

Hungarians who dare to show solidarity with refugees, who are ashamed of

their government, and who remember what happened to our Jewish

Hungarian compatriots in 1944.

Hungarian

democrats now find themselves unwelcome refugees in their own country,

ruled by a government that would gladly transport them to the Austrian

border.

Csapdát rejt a horvát határzár: image via Index,hu @indexhu, 24 September 2015

Attila József: Night on the Outskirts

#refugeecrisis reportage from the Hun-Aut #border by photographer Balint Hirling for Vs.hu: image via Levente Hernadi @Lvnte, 22 September 2015

Slowly the light’s net is lifted

Out of the yard, and our kitchen

Fills with darkness

Like the hollows deep in a pool.

Out of the yard, and our kitchen

Fills with darkness

Like the hollows deep in a pool.

Silence --

The scrubbing brush creeps to life,

Above it, a patch of wall

Hesitates, hangs, not sure

Whether to stay or fall.

The scrubbing brush creeps to life,

Above it, a patch of wall

Hesitates, hangs, not sure

Whether to stay or fall.

A night that wears oily rags

Heaves a sigh,

Halts in the sky;

Then settles on the outskirts,

Waddles over the square

And lights a bit of moon to see by.

Heaves a sigh,

Halts in the sky;

Then settles on the outskirts,

Waddles over the square

And lights a bit of moon to see by.

Like ruins the factories loom.

But inside them a denser gloom

Even now is being produced. It sets,

A foundation for silence.

But inside them a denser gloom

Even now is being produced. It sets,

A foundation for silence.

Through the windows of textile mills

Fly moonbeams in sheaves --

Moon thread till morning weaves

On motionless looms a fabric

Of girl workers’ dreams.

Fly moonbeams in sheaves --

Moon thread till morning weaves

On motionless looms a fabric

Of girl workers’ dreams.

Farther on, like a cloistered graveyard,

The foundry, bolt makers, cement works –-

Echoing family crypts.

Too well these workshops keep

The secret of resurrection.

The foundry, bolt makers, cement works –-

Echoing family crypts.

Too well these workshops keep

The secret of resurrection.

A cat’s claws on the fence:

And the simple night-watchman sees

A ghost, a flashing signal.

Coolly gleam

The beetle-backed dynamos.

And the simple night-watchman sees

A ghost, a flashing signal.

Coolly gleam

The beetle-backed dynamos.

A train whistle blows.

Dampness seeps into

The shadows, the boughs

Of a fallen tree.

The dust on the road grows heavy.

The shadows, the boughs

Of a fallen tree.

The dust on the road grows heavy.

In the street a policeman,

A muttering workman, pass.

Now and then a comrade

Flits past with leaflets -

Keen as a dog on the track ahead,

Listening, cat-like, for noises behind him;

avoiding the lamps.

A muttering workman, pass.

Now and then a comrade

Flits past with leaflets -

Keen as a dog on the track ahead,

Listening, cat-like, for noises behind him;

avoiding the lamps.

The tavern door belches out

A tainted light, its windows

Vomit, leaving puddles.

Inside, a half-stifled lamp

Slowly swings,

A solitary labourer keeps awake.

While the inn-keeper snores and wheezes,

He bares his teeth at the wall,

His grief climbs the stairs. He weeps,

Cries out for the revolution.

A tainted light, its windows

Vomit, leaving puddles.

Inside, a half-stifled lamp

Slowly swings,

A solitary labourer keeps awake.

While the inn-keeper snores and wheezes,

He bares his teeth at the wall,

His grief climbs the stairs. He weeps,

Cries out for the revolution.

Cold metal, the water clinks.

A stray mongrel, the wind

Wanders. Its great tongue hangs

To touch the water, and laps it.

Straw mattresses are the rafts

That drift on night’s currents.

A stray mongrel, the wind

Wanders. Its great tongue hangs

To touch the water, and laps it.

Straw mattresses are the rafts

That drift on night’s currents.

The warehouse’s hulk is aground.

In the foundry’s iron dinghy

The smelter dreams red babies

Into the metal moulds.

In the foundry’s iron dinghy

The smelter dreams red babies

Into the metal moulds.

All is damp, and heavy.

Mildew draws a map

Of misery’s regions.

And there, on the dry meadows,

Rags and paper litter

The ragged, papery grass.

How they would whirl and fly!

They stir, but inertia holds them.

Mildew draws a map

Of misery’s regions.

And there, on the dry meadows,

Rags and paper litter

The ragged, papery grass.

How they would whirl and fly!

They stir, but inertia holds them.

Night, your sluggish breeze

Is a flapping of soiled sheets.

Like frayed muslin to cord

You cling to the old sky,

As wretchedness clings to life.

Is a flapping of soiled sheets.

Like frayed muslin to cord

You cling to the old sky,

As wretchedness clings to life.

Night of the poor, be my coal,

Smoulder here on my heart,

Melt the iron in me, to make

An anvil that never will split,

A hammer that clangs and glints,

A smooth blade for victory, night!

Smoulder here on my heart,

Melt the iron in me, to make

An anvil that never will split,

A hammer that clangs and glints,

A smooth blade for victory, night!

Grave this night is, and heavy.

I too shall sleep now, my brothers.

May our souls not be smothered by want.

Nor our bodies be bitten by vermin.

I too shall sleep now, my brothers.

May our souls not be smothered by want.

Nor our bodies be bitten by vermin.

Attila József (1905-1937), Night on the outskirts (Külvárosi éj), 1932, translated from the Hungarian by Michael Hamburger in Attila József: Poems (Danubio, 1966)

Bus collides with tram in the rain, Budapest: photo by Gábor Olvasónk via index,hu, 25 September 2015

Orbán Viktor megnyerte az MSZP-Jobbik-Liberálisok triót is: image via Index,hu @indexhu, 24 September 2015

Risking everything on their long walk to freedom #Hungary @helenpercival84 @AFPblogs: image via Agence France-Prese, 25 September 2015

Helen Percival: A Long Walk

A child presses his face against the window on a Hongarian police bus, near Röszke, at the the Hungarian-Serbian border, on 27 August 2015: AFP photo / Attila Kisbenedek

Correspondent / behind the news: A long walk to freedom: Helen Percival, AFP Correspondent, 25 September 2015

BUDAPEST, September 23, 2015 - A little Syrian boy

appears between the legs of a line of Hungarian police. He grips a dirty

plastic bag of bread rolls and is clearly lost.

Standing in the rain, he quietly looks up at the officers.

The police gesture to a family climbing on a nearby bus headed to a

migrant camp, asking if he belongs to them. They firmly shake their

heads and move on.

All the while, in the shoving and confusion, the little boy looks on

as the rain falls. With barely any hesitation, the police lift the boy

onto the bus, the doors close and the bus pulls away.

That was 45 seconds at Röszke migrant collection point in Hungary.

Refugees cross the Hungarian-Serbian border on 14 September 2015: AFP Photo / Armend Nimani

There is a fine line between witnessing life as 'the journalist', and

engaging with what you see on a human level. For me, that line was

crossed many times while I was in Hungary.

I'd flown to Budapest five days earlier and headed straight to the

Keleti train station where people from Syria, Afghanistan and Iraq were

waiting to board trains to Vienna.

The scene was relatively peaceful.

Weary mothers were waiting for trains, smiling weakly as their children

giggled and tickled each other on the floor.

At first, I was hesitant while filming, aware of their exhaustion and

vulnerability, and knowing how I would feel if I was in their shoes and

a camera was trailing me. But I was there to bear witness, and they

withstood the cameras and photographs with a dignified grace I became

familiar with over the coming week.

It was early September and tensions were building on the border with

Serbia, so AFP photographer Attila Kisbenedek and I made the two and

half hour drive to Röszke. I was grateful to be alongside Attila, who

knew the lay of the land and as a Hungarian, could communicate with

local people and the police.

Professional and personal boundaries were constantly tested during

this mission. For example, during our assignment Attila helped pull a

young boy from a crush of people, which some may say crosses the

professional boundaries of journalism.

Attila and I arrived at midnight at the Röszke collection point.

There was an eerie quiet, hundreds of people lying in sleeping bags out

under the stars.

The "migrant collection point" near Röszke on 9 September 2015: AFP photo / Attila Kisbenedek

Occasionally, you could hear the muffled cry of a baby, a hacking

cough, or the quiet talk of volunteers handing out food to bleary eyed

men and women. One young man -- a sculptor from Syria -- made space for me

on a patch of damp cardboard outside his tent, as he furiously sketched

in charcoal.

With manic stokes he brought to life a hallowed, gaunt face with dark

circles under the eyes and a pained expression. I asked him who the man

was and he simply turned and looked at me. Then I saw it. The

resemblance to the artist took my breath away. The moment was broken

when the tent behind us was unzipped from the inside and his wife

gruffly passed him a small whimpering child. “My son needs the toilet”,

he said apologetically and disappeared into the darkness. I felt

embarrassed and privileged to witness such an intimate moment.

A migrant family arrives in Hungary near Röszke on 10 September 2015: AFP photo / Attila Kisbenedek

After a few hours of sleep we were back at the camp at dawn. Skeins

of smoke from small camp fires wafted into the damp atmosphere, along

with the quiet talk of people rousing themselves for another day of

waiting, of uncertainty and hope. It was only early September but

temperatures dropped to 5 degrees overnight, so it was too cold for most

to sleep. But the striking sunrise made this bleak situation

exceptionally beautiful.

I tentatively approached a group of Syrian men huddled around a fire.

They took one look at the AFPTV camera and excitedly ushered me into

their inner circle. They passed me one of the ham rolls they had been

given by local volunteers and started teaching me a few Arabic

greetings, laughing ecstatically when I repeated the words in my British

accent. One man, with a cheeky twinkle in his piercing green eyes told

me in broken English of his journey from Syria and his ambition to reach

Germany. There was hope and humour in his story.

We snatched a few more hours of sleep in the afternoon at the hotel

but I was woken by a call from Attila saying we had to leave

immediately. A group of men and women were running along a nearby train

line after breaking out of the collection point and through police

barricades.

My adrenaline surged as I filmed police resisting the group’s attempt

to push forward, but after a short standoff the officers let them pass,

and ended up escorting them along the track.

A Syrian in his late fifties walking along the track furiously shouted to me: “Are we not humans too?!”

Police

officers stop a group of migrants who broke out of the "collection

point" near Röszke village on 9 September 2015: AFP photo / Csaba

Segesvari

Exhausted and exasperated the engineer explained his fury at being

treated like a criminal. He had attempted the deadly sea crossing to

Greece three times before finally making it. On one occasion the men

spent two hours swimming around the boat in freezing water to prevent it

from sinking, as women and children sat inside. His anger turned to

quiet dejection when he told me of his wife and four daughters still in

Aleppo.

He started to cry and asked me to stop filming. It was a hot day and he offered me water while apologising for his smell -- he hadn't been able to wash for days. It was in that moment I realised a person can be stripped of their humanity in many different ways.

Migrants walk on a road near Rözske on 8 September 2015: AFP photo / Attila Kisbenedek

That night we drove to a nearby petrol station where people smugglers

were openly piling families into cars and driving them to Budapest. The

mood was charged -- furtive glances, quick hand gestures, wide-eyed men,

women and children anxiously deciding if they should take the risk. I

began filming but quickly realised this was no place for cameras.

Not far away, another stand-off between police and a group of

migrants was unfolding. Under the cover of darkness fear and tension

permeated the air, a policeman waved his light in my face and ordered me

to turn the top light off on my camera. Suddenly a cloud streamed above

the crowd -- tear gas had been fired.

A young migrant lies on the road after police threw tear gas near Röszke on 8 September 2015: AFP photo / Attila Kisbenedek

A piercing wail filled the air and a group of men broke free of the

crowd carrying two limp bodies. They doused the young men in water.

Cameras swarmed as the two men remained motionless. “Where's the

ambulance?” one man screamed at a policeman standing by nonchalantly.

Finally the two wounded men sputtered, wretched and gasped for

breath. They remained unmoving on the floor, covered in water and

gagging occasionally. A journalist behind me leaned in close and asked

if I thought they were faking it. I couldn't even muster a response.

The coming days were raw, gritty and heavy with a sense of witnessing

a painful moment in history. The few simple Arabic greetings the men

from Syria had taught me became invaluable.

A Serbian border watchtower near Röszke, on 10 September 2015: AFP photo / Attila Kisbenedek

As a blonde woman with a large video camera I was initially viewed with suspicion, but a quick 'Walaikum Salam', meaning peace be with you, and people's eyes would light up. They would smile and shout back 'Salam Walaikum'.

One beautiful young woman offered me figs while telling me that she

had escaped Syria after her parents were killed. She said there was no

safe place on earth for her to go now. Gently smiling she told me “I'm

scared, I'm just...scared.”

After the release of the shocking video of migrants being “fed like

animals” by police in a camp, we drove straight to a nearby centre for

migrants. It was reminiscent of a World War II camp, with barbed wire

fences, stony-face policemen smoking along the perimeters, and patrols

with dogs.

Refugees warm up at the "migrant collection point" near Röszke on 8 September 2015: AFP photo / Attila Kisbenedek

Speaking to people through the wire we saw confusion, exhaustion, and

frustration. But there was still the prevailing hope that they would

soon be released and allowed to continue on their journey. I was glad

for the company of my colleague Sonia Bakaric as we were escorted by a

police officer around the perimeter.

I gestured to a guard with a German Shepherd, asking if I could film

him. He shook his head and partly released the dog’s lead, sending the

canine into a barking frenzy. I jumped and he and his two colleagues

burst out laughing and continued to smoke.

It was a real wrench to leave the border. As we drove towards the

Hungarian capital tanks were rolling in to reinforce police, and a sense

of foreboding hung heavily in the air.

Budapest’s kebab restaurants, rowdy tourists and sex shops were a

shock to the system.

When I got back to Keleti station I realised that

the scene had changed dramatically in just a few days. Hundreds of

people were camped out, men were washing and shaving using a makeshift

tap, charities handed out food and clothing and a throng of people

waited patiently to board trains to Vienna.

A group of tourists wearing sunglasses and smart clothes meandered

through the station smiling and taking pictures on their smart phones.

I spoke to one young Syrian man who showed me the mottled skin of his

two-year-old niece, caused by drinking dirty water in a camp in Greece.

An hour later I watched him board a train for Vienna -- his face a mix

of relief and anxiety.

Police

block refugees trying to board a train to Austria in Budapest's Keleti

Station on 10 September 2015: AFP Photo / Ferenc Isza

But in the turmoil, hope and goodwill also reigned at Keleti station.

Syrians laughed while forcing chocolate bars, bread, cheese and dried

biscuits into my hands. Volunteers worked on little to no sleep. One man

handed out free train tickets to Vienna. A Farsi speaker who had

travelled from Austria offered his services as a translator for people

from Iraq and Iran. I learned that desperation, darkness and division

can also bring out the power and unity of the human spirit.

My week in Hungary felt more like a month and while relieved to be

heading home, it was painful to leave behind these people and their

important stories. I was told about one Syrian man who said “You only

leave home if it's a shark's mouth.” I knew that the people I met would

only endure fear, exhaustion and uncertainty if a shark's mouth was the

alternative.

With a mixture of relief and regret I piled onto the plane back to

London, Heathrow. As we soared over Europe, effortlessly crossing the

borders others are risking their lives to breach, my heart and mind was

with the people on the ground, risking everything to complete their long

walk to freedom.

Helen Percival is an AFP video reporter based in London

At the "migrant collection point" near Röszke on 9 September 2015: AFP photo / Peter Kohalmi

Syrian children play at an improvised play-ground

of the northern city of Aleppo

AFP PHOTO /BARAA AL-HALABI: image via baraa al halabi @baraaalhalabi, 24 September 2015

The joy of children Aleppo: image via baraa al halabi @baraaalhalabi, 25 September 2015

Little girl braves barriers to deliver migrant message to pope: image via Agence France-Presse @AFP, 24 September 2015

Stunning pics by @indexhu's János Bődey. #Refugees having a rest in a #Serbia-n cemetery near the #Croatia-n border: image via Szaboics Panyi #panyiszaboics, 24 September 2015

Stunning pics by @indexhu's János Bődey. #Refugees having a rest in a #Serbia-n cemetery near the #Croatia-n border: image via Szaboics Panyi #panyiszaboics, 24 September 2015

The Emigrants: Honoré Daumier, c. 1850, plaster (Musée du Louvre, Paris)

A worker walks past a bucket-wheel excavator in the Welzow Sued open-pit lignite coal mine on Friday near Welzow, Germany: photo by Sean Gallup via FT Photo Diary, 25 September 2015

Attila József: Consciousness

See, here inside is the suffering,

out there, sure enough, is the explanation.

Your wound is the world -- it burns and rages

and you feel your soul, the fever.

You are a slave so long as your heart rebels -

you become free by making it your pleasure

not to build yourself the kind of house

in which the landlord settles down.

out there, sure enough, is the explanation.

Your wound is the world -- it burns and rages

and you feel your soul, the fever.

You are a slave so long as your heart rebels -

you become free by making it your pleasure

not to build yourself the kind of house

in which the landlord settles down.

.

He has fully become a man

who has in his heart no mother, father,

who knows that he gets life

only as an extra to death

and, like something found, he will give it back

at any time, that's why he keeps it safe,

who is not a god and not a priest

either to himself or anyone.

who has in his heart no mother, father,

who knows that he gets life

only as an extra to death

and, like something found, he will give it back

at any time, that's why he keeps it safe,

who is not a god and not a priest

either to himself or anyone.

.

Like a pile of hewn timber

the world lies heaped up on itself,

one thing presses and squeezes and

interlocks with the other,

so each is determined.

Only what is not has a bush,

only what will be is a flower,

what is crumbles into fragments.

the world lies heaped up on itself,

one thing presses and squeezes and

interlocks with the other,

so each is determined.

Only what is not has a bush,

only what will be is a flower,

what is crumbles into fragments.

.

In the goods station yard

I flattened myself against the foot of the tree

like a slice of silence; grey weeds

reached up to my mouth, raw and queerly sweet.

Dead still I watched the guard, (what was he sensing?)

and, on the silent waggons,

his shadow which kept obstinately jumping

upon the lustrous dew-laden coal-lumps.

I flattened myself against the foot of the tree

like a slice of silence; grey weeds

reached up to my mouth, raw and queerly sweet.

Dead still I watched the guard, (what was he sensing?)

and, on the silent waggons,

his shadow which kept obstinately jumping

upon the lustrous dew-laden coal-lumps.

.

I live by the railway line. Many trains

go past here and, time and again,

I watch the lighted windows fly

through the fluttering fluff-darkness.

So through eternal night

rush illuminated days

and I stand in each cubicle of light,

I lean upon my elbows and am silent.

go past here and, time and again,

I watch the lighted windows fly

through the fluttering fluff-darkness.

So through eternal night

rush illuminated days

and I stand in each cubicle of light,

I lean upon my elbows and am silent.

Attila József (1905-1937), from Consciousness (Eszmelet), 1934, translated from the Hungarian by Michael Beevor in Attila József: Poems (Danubia, 1966)

A child sits behind a fence as refugees and migrants wait for a train heading to Serbia near the Macedonian-Greek border on Friday: photo by Armend Nimani/AFP, 25 September 2015

Macedonian border police attempt to manage the passage of refugees and migrants to southern Macedonia, September 10. Thousands of people braved torrential downpours to cross Greece's northern border with Macedonia: image by Freedom House, 15 September 2015

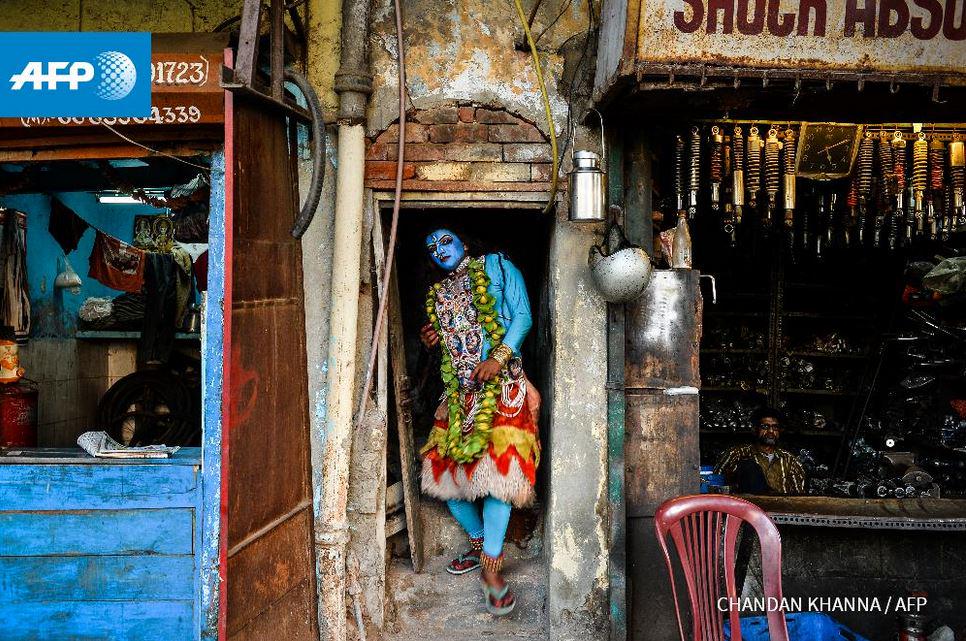

An artist dressed as Hindu goddess Kali leaves home for a religious procession in New Delhi, India: image via Agence France-Presse @AFP, 24 September 2015

Ultra-Orthodox Jews check palm fronds to determine if they are ritually acceptable as one of the four items used as a symbol on the Jewish holiday of Sukkot in Jerusalem, Thursday: photo by Oded Balilty/AP, 24 September 2015

Muslim pilgrims making their way to cast stones at a pillar symbolizing the stoning of the devil in Mina, near the holy city of Mecca, Saudi Arabia, on Thursday: photo by Mosa'Ab Elshamy/Associated Press via New York Times, 24 September 2015

An Indonesian mother tends to her daughter during the Eid Al-Adha festival at the Al-Azhar mosque in Jakarta. Muslims across the world celebrate the annual festival of Eid al-Adha, or the Festival of Sacrifice, which marks the end of the Hajj pilgrimage to Mecca: photo by Adek Berry/AFP, 24 September 2015

Eid Al-Adha: Indonesia: image via Agence France-Presse @AFP, 24 September 2015

#South Africa celebration of #EidAlAdha in Lenasia, where thousands gathered for the prayer @AFPphoto @mlongari: image via AFP Photo Department @AFPphoto, 25 September 2015

Pakistani Muslims offer #Eid al-Adha prayers at the Badshahi Mosque in Lahore: image via AFP Photo Department @AFPphoto, 25 September 2015

#India - - Snapshots of Chand Baori stepwell in Abhaneri, Rajasthan. By @Alex_Ogle #AFP: image via AFP Photo Department @AFPphoto, 25 September 2015

Great old stepwell in Rajasthan, India - open to all for a few hours on one day each year to mark Hindu festival @AFP: image via Alex Ogle @Alex_Ogle, 24 September 2015

#India - - Snapshots of Chand Baori stepwell in Abhaneri, Rajasthan. By @Alex_Ogle #AFP: image via AFP Photo Department @AFPphoto, 25 September 2015

Nepalese Hindu women, dressed in red, are led by a priest as they recite prayers during celebrations of the Teej festival at the Pashupatinath temple area in Kathmandu: photo by Prakash Mathema/AFP, 16 September 2015

Muslim students pray for rain to put out the fires which enveloped the region at Palembang 1 senior high school in Palembang, South Sumatra, Indonesia, on Thursday: photo by Feny Selly/Antara Foto/Reuters, 17 September 2015

Nepalese Hindu women take a ritual bath in the Bagmati River during the Rishi Panchami festival in Kathmandu. Rishi Panchami marks the end of the three-day long Teej festival, in which married women fast and pray for the good health of their husbands to Shiva, the Hindu god of destruction, while unmarried women wish for handsome husbands and happy conjugal lives.: photo by Mathema Prakash/AFP, 18 September 2015

An Afghan boy eats an ice cream as he waits for customers at a

livestock market ahead of the sacrificial Eid al-Adha festival in

Mazar-i-Sharif on Monday. Muslims across the world are preparing to

celebrate annual festival of Eid al-Adha or the festival of sacrifice

which marks the end of the Hajj pilgrimage to Mecca: photo by Farshad Usyan/AFP, 21 September 2015

Palestinian women from the so-called Murrabit group raise copies of the Koran, Islam’s holy book, and shout slogans in front of Israeli security forces during a protest against Jewish groups visiting the Al-Aqsa mosque compound in Jerusalem's old city on Tuesday: photo by Ahmad Gharabli/AFP, 22 September 2015

Ultra-Orthodox Jews of the Dorog Hassidic sect gather around a

butcher just before he slaughter a chicken as part of the Kaparot

ritual, in which it is believed that one transfers one’s sins from the

past year into the chicken, in the ultra-Orthodox city of Bnei Brak near

Tel Aviv, Israel, Tuesday: photo by Oded Balilty/AP, 22 September 2015

Israelis walk in the middle of an empty street during the Jewish

holiday of Yom Kippur, in Jerusalem, Wednesday. Yom Kippur, or ‘Day of

Atonement,’ is the holiest of Jewish holidays when observant Jews atone

for the sins of the past year and the nation comes to almost a complete

standstill: photo by Mahmoud Illean/AP, 23 September 2015

Israelis walk in the middle of an empty street during the Jewish

holiday of Yom Kippur, in Jerusalem, Wednesday. Yom Kippur, or ‘Day of

Atonement,’ is the holiest of Jewish holidays when observant Jews atone

for the sins of the past year and the nation comes to almost a complete

standstill: photo by Mahmoud Illean/AP, 23 September 2015

A Muslim girl touches the holy Kaaba at the Grand Mosque: image via Reuters Top News @Reuters, 24 September 2015

César Vallejo: Piedra negra sobre una piedra blanca (Black stone on top of a white stone)

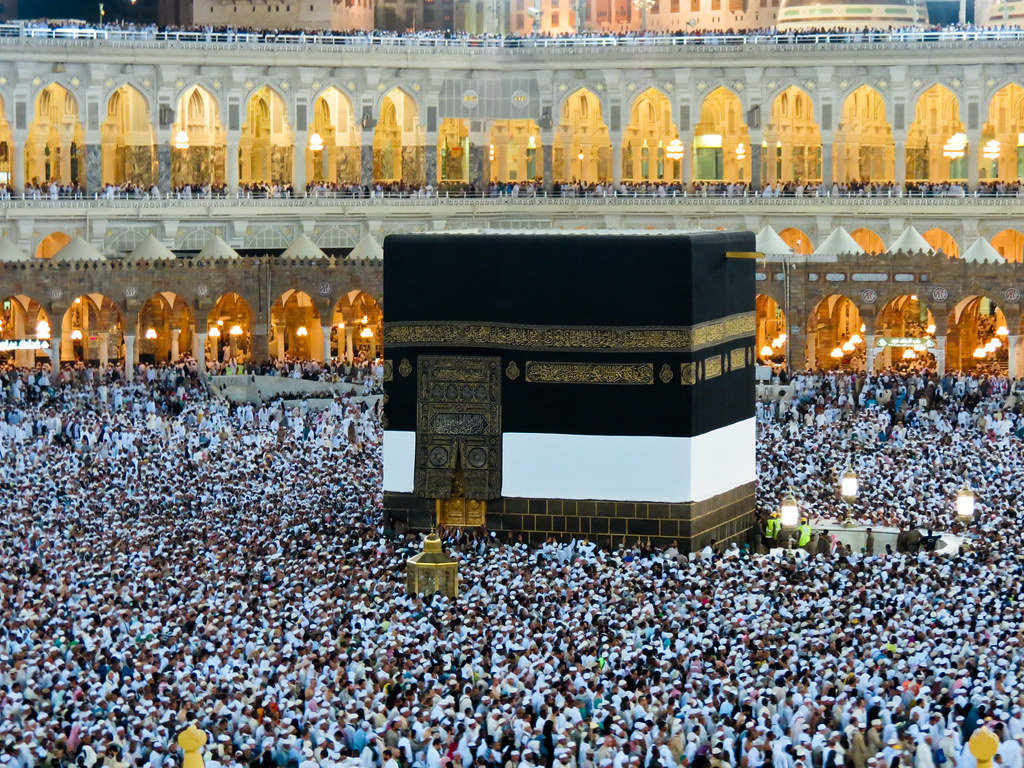

البيت العتيق -- The Primordial House "Kaaba" at Mecca during hajj season: photo by A.S. Dhanny, 19 October 2012

I shall die in Paris, in a rainstorm,

On a day I already remember.

I shall die in Paris -- it does not bother me --

Doubtless on a Thursday, like today, in autumn.

On a day I already remember.

I shall die in Paris -- it does not bother me --

Doubtless on a Thursday, like today, in autumn.

It shall be a Thursday, because today, Thursday

As I put down these lines, I have set my shoulders

To the evil. Never like today have I turned,

And headed my whole journey to the ways where I am alone.

César Vallejo is dead. They struck him,

All of them, though he did nothing to them,

They hit him hard with a stick and hard also

With the end of a rope. Witnesses are: the Thursdays,

The shoulder bones, the loneliness, the rain, and the roads...

Panorama of Masjid al-Haram (the Grand Mosque) at Mecca, Saudi Arabia: photo by Bluemango2z, 22 December 2007

Me moriré en París con aguacero,

un día del cual tengo ya el recuerdo.

Me moriré en París y no me corro

tal vez un jueves, como es hoy, de otoño.

un día del cual tengo ya el recuerdo.

Me moriré en París y no me corro

tal vez un jueves, como es hoy, de otoño.

Jueves será, porque hoy, jueves, que proso

estos versos, los húmeros me he puesto

a la mala y, jamás como hoy, me he vuelto,

con todo mi camino, a verme solo.

César Vallejo ha muerto, le pegaban

todos sin que él les haga nada;

le daban duro con un palo y duro

los días jueves y los huesos húmeros,

la soledad, la lluvia, los caminos...

César Vallejo (1892-1938): Piedra negra sobre una piedra blanca (Black stone on top of a white stone) from Poemas Humanos (Human Poems) (1923-1938), 1938; English translation by Thomas Merton, 1960

Deadly haj disaster the worst to strike the annual pilgrimage for 25 years: image via Reuters Top News @Reuters, 24 September 2015

UPDATE: Death toll at Saudi Haj crush rises to 453 and 719 injured: image via Reuters Top News @Reuters, 24 September 2015

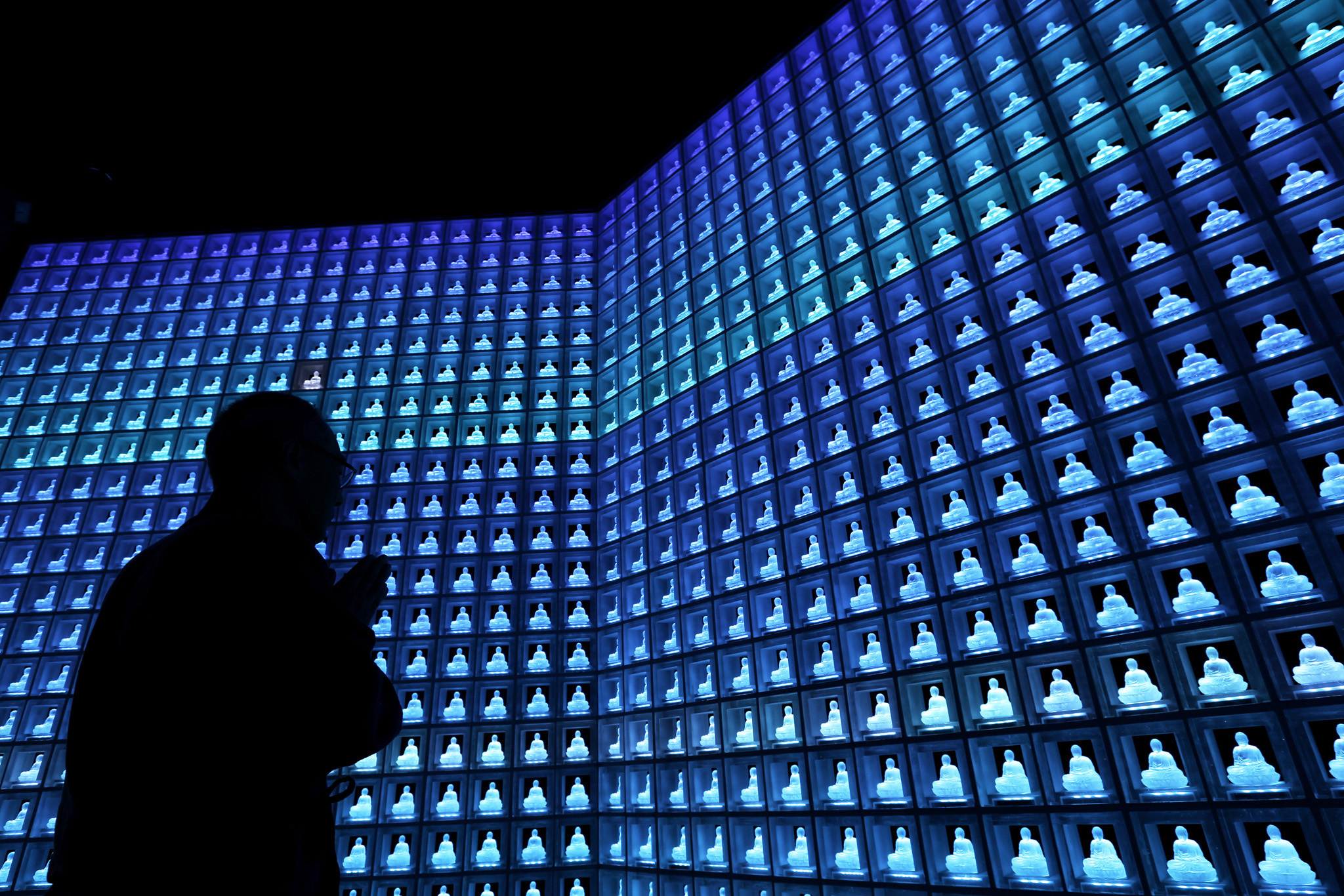

Taijun Yajima, chief priest at Koukokuji temple, stands for a photograph inside the Ruriden columbarium as glass Buddha statues sit illuminated by light-emitting diodes (LED) at the Koukokuji temple in Tokyo, Japan: photo by Kiyoshi Ota/Bloomberg, 11 September 2015

Taijun Yajima, chief priest at Koukokuji temple, stands for a

photograph inside the Ruriden columbarium as glass Buddha statues sit

illuminated by light-emitting diodes (LED) at the Koukokuji temple in

Tokyo, Japan: photo by Kiyoshi Ota/Bloomberg, 11 September 2015

y ¿qué une a la gente?...

ReplyDeletenecesidades ?

ReplyDeletedeseos ?

la desesperación ?

fe?

sangre?

memoria?

creo que más que todo el dolor...

ReplyDeleteThey stir, but inertia holds them

ReplyDeleteThis is the thing. Perhaps the true revolutionary moment has long sense slipped our grasp.

Vallejo's poem - at the heart.

El dolor, sí.

ReplyDeleteSin embargo, un dolor que no se puede escapar, ya que la rodea, encierra, sigue cuando intenta mover.

No es un hecho de la física, sino un hecho de la condición humana, "la forma en que viven ahora" (The Way We Live Now) -- el miedo, la desconfianza de los demás ...

Este dolor es inevitable -- una especie de inercia, ya que el buen hombre dice.

El poeta Vallejo también fue un refugiado, de las clases. Pero siempre huía solo. A más terrible especie de tristeza ...

Duncan is surely right. Vallejo's poem lies at the heart of everything, the perpetual rainy Thursdays and dry Thursdays, the neverending funeral cortège of lost revolutionary moments.

Vallejo fue un exiliado. El poeta Attila Jószef, también - un exiliado en su propia tierra, en su propia vida ...