.

Abandoned Soviet T-34 tank, Ukraine: photographer unknown, 1942 (Deutsches Bundesarchiv / German Federal Archive)

Meanwhile

the sun was coming up from the horizon of green, and gradually the

hoarse call of birds was becoming shriller and more lively. The sun

seemed to beat down hammer-like on the cast-iron plate of the lagoons. A

shiver ran along the water with a kind of metallic vibration and

spread to the surface of the pools, just as the sound of a violin

spreads like a shiver along the arms of a musician. By

the roadside, and here and there in the cornfields, were overturned

cars, burned trucks, disemboweled armored cars, abandoned guns, all

twisted by explosions. But nowhere a man, nothing living, not even a

corpse, not even any carrion. For miles and miles there was only dead

iron. Dead bodies of machines, hundreds upon hundreds of miserable steel

carcasses. The stench of putrifying rose from the fields and the

lagoons. The cockpit of a plane was sticking up from the mud in the

middle of a pool. The German cross was clearly discernible: it was a

Messerschmitt. The smell of rotting iron won over the smell of men and

horses -- that smell of old wars; even the smell of grain and the

penetrating, sweet scent of sunflowers vanished amid that sour stench of

scorched iron, rotting steel, dead machinery. The clouds of dust

lifted by the wind from the far ends of the vast plain carried no smell

of organic matter with them but a smell of iron filing. And all the

time, while I was pushing into the heart of the plain and approached

Nemirovskoye, the smell of iron and of petrol grew stronger in the dusty

air; even the grass seemed to be permeated with that undefinable,

strong and exhilarating smell of gasoline, as if the smell of men and

beasts, the smell of trees, of grass and mud was overcome by that odor

of gasoline and scorched iron.

*

It had been raining for days and days and the sea of Ukrainian mud slowly spread beyond the horizon. It was the high tide of autumn in the Ukraine. The deep black mud was everywhere swelling like dough when yeast begins to work. The heavy smell of mud was borne by the wind from the end of the vast plain and mingled with the odor of uncut grain left to rot in the furrows, and with the sweetish stale odor of sunflowers. One by one the seeds dropped out of the black pupils of the sunflowers, one by one fell the long yellow eyelashes from around the large, round eyes, blank and void like the eyes of the blind.

The German soldiers returning from the front line, when they reached the village squares, dropped their rifles on the ground in silence. They were coated from head to foot in black mud, their beards were long, their hollow eyes looked like the eyes of the sunflowers, blank and dull. The officers gazed at the soldiers and at the rifles lying on the ground, and kept silent. By then the lightning war, the Blitzkrieg, was over, the Dreizigjährigerblitzkrieg, the thirty year lightning war, had begun. The winning war was over, the losing war had begun. I saw the white stain of fear growing in the dull eyes of German officers and soldiers. I saw it spreading little by little, gnawing at the pupils, singeing the roots of the eyelashes and making the eyelashes drop one by one, like the long yellow eyelashes of the sunflowers. When Germans become afraid, when that mysterious German fear begins to creep into their bones, they always arouse a special horror and pity. Their appearance is miserable, their cruelty sad, their courage silent and hopeless. That is when the Germans become wicked. I repented being a Christian. I felt ashamed of being a Christian.

Abandoned Soviet KW-1 tank, Ukraine: photographer unknown, 1942 (Deutsche Bundesarchiv / German Federal Archive)

*

It had been raining for days and days and the sea of Ukrainian mud slowly spread beyond the horizon. It was the high tide of autumn in the Ukraine. The deep black mud was everywhere swelling like dough when yeast begins to work. The heavy smell of mud was borne by the wind from the end of the vast plain and mingled with the odor of uncut grain left to rot in the furrows, and with the sweetish stale odor of sunflowers. One by one the seeds dropped out of the black pupils of the sunflowers, one by one fell the long yellow eyelashes from around the large, round eyes, blank and void like the eyes of the blind.

The German soldiers returning from the front line, when they reached the village squares, dropped their rifles on the ground in silence. They were coated from head to foot in black mud, their beards were long, their hollow eyes looked like the eyes of the sunflowers, blank and dull. The officers gazed at the soldiers and at the rifles lying on the ground, and kept silent. By then the lightning war, the Blitzkrieg, was over, the Dreizigjährigerblitzkrieg, the thirty year lightning war, had begun. The winning war was over, the losing war had begun. I saw the white stain of fear growing in the dull eyes of German officers and soldiers. I saw it spreading little by little, gnawing at the pupils, singeing the roots of the eyelashes and making the eyelashes drop one by one, like the long yellow eyelashes of the sunflowers. When Germans become afraid, when that mysterious German fear begins to creep into their bones, they always arouse a special horror and pity. Their appearance is miserable, their cruelty sad, their courage silent and hopeless. That is when the Germans become wicked. I repented being a Christian. I felt ashamed of being a Christian.

Curzio Malaparte (born Kurt Erich Sickert, 1898-1957): from Kaputt, 1943, translated from the Italian by Cesare Foligno

Abandoned Soviet KW-1 tank, Ukraine: photographer unknown, 1942 (Deutsche Bundesarchiv / German Federal Archive)

Destroyed aircraft, Ukraine, Soviet Union, beyond the Dnieper: photographer unknown, 2 September 1941 (Deutsches Bundesarchiv/German Federal Archive)

Burning Soviet T-34 tank, Ukraine: photographer unknown, 1941 (Deutsches Bundesarchiv/German Federal Archive)

Burning houses mark the struggles of the 6th army in the advance toward Stalingrad: photo by Horst Grund, 21 June 1942 (Deutsches Bundesarchiv / German Federal Archive)

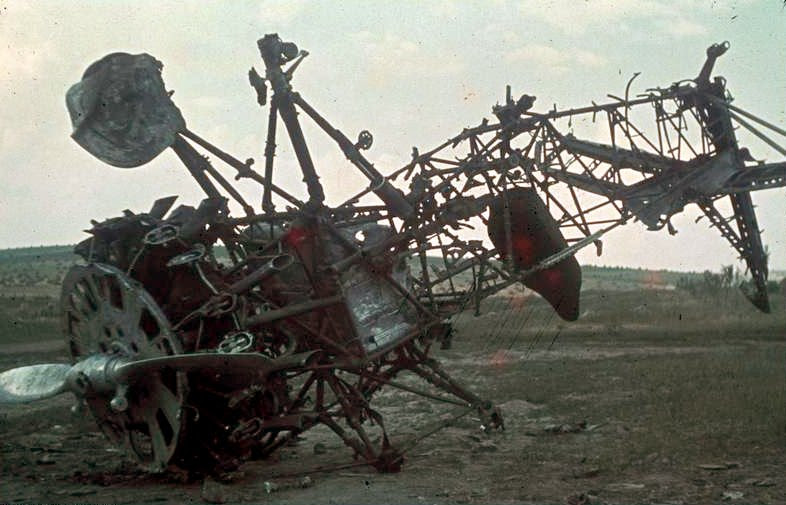

Wreckage of Soviet Polikarpov I-153, during the Russian retreat: photo by Horst Grund, 21 June 1942 (Deutsche Bundesarchiv / German Federal Archive)

Abandoned Soviet KW-1 tank on the steppes near Stalingrad: photo by Horst Grund, August 1942 (Deutsches Bundesarchiv /German Federal Archive)

Abandoned Soviet T-34 tanks: photo by Horst Grund, 21 June, 1942 (Deutschse Bundesarchiv / German Federal Archive)

Abandoned Soviet T-34 tanks, during the Russian retreat: photo by Horst Grund, 21 June, 1942 (Deutsches Bundesarchiv /German Federal Archive)

Abandoned Soviet T-34 tanks, during the Russian retreat: photo by Horst Grund, 21 June, 1942 (Deutsches Bundesarchiv /German Federal Archive)

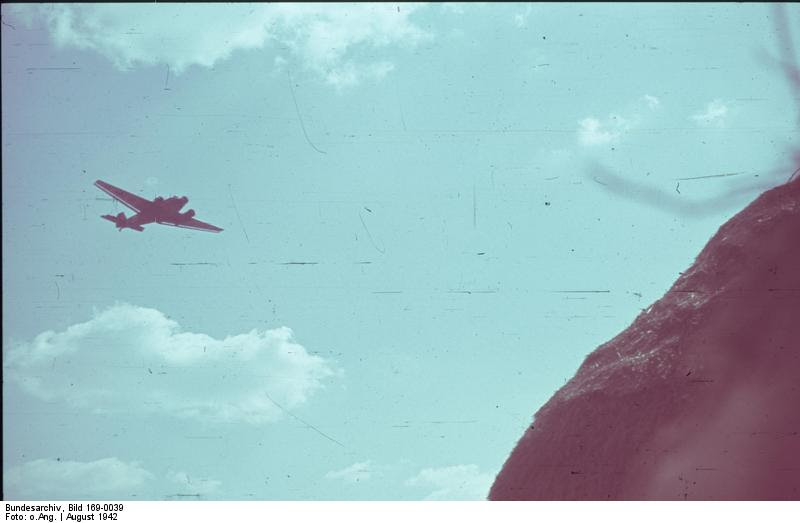

Junkers JU-52 in flight over Ukraine, August 1942: photo by Horst Grund, 1942 (Deutsches Bundesarchiv /German Federal Archive)

German IV Panzer odvancing in Ukraine, 1941: photo by Horst Grund, 1941 (Deutsches Bundesarchiv / German Federal Archive)

Fieseler Fi 156 transport plane at air strip under construction on the steppes near Stalingrad, September 1942: photo by Horst Grund, 1942 (Deutsches Bundesarchiv / German Federal Archive)

View of Stalingrad-South, 23 September 1942: photo by Horst Grund, 1942 (Deutsches Bundesarchiv / German Federal Archive)

10 comments:

“one by one fell the long yellow eyelashes from around the large, round eyes, blank and void like the eyes of the blind”

That summarizes my own state of mind about current events in the Ukraine pretty well.

If I can, I will try to reacquaint myself with relevant history today. For what it’s worth (not much), I have significant connections with the Ukraine on both sides of my family. I just don’t have significant connections with my family.

Watching one of the Sunday news programs treating the subject of the Ukraine this morning was dispiriting. Sen. Ayotte of New Hampshire just seemed confused and unable to say much of anything that was assertive. Sen. Durbin of Illinois, who is a slippery individual, was all over the place – at once a champion of liberty (anyone’s/everyone’s) and at the same time saying that whatever the U.S.’s position was or would be – something he could neither describe nor define -- it was both morally right and would be politically effective.

The Malaparte makes remarkable reading. The photographs are really devastating and put you right in the frame. Curtis

After you first introduced me to Malaparte some time back, I read a couple of his books. They’re like no other account of WW II that I know, from any fighting front. “ The white stain of fear growing in the dull eyes . . .” describes well the functional insanity that war is. Both Malaparte and Gottfried Benn intrigue me as writers and thinkers who flirted briefly with fascism, then renounced it, but never escaped its havoc.

Goddard filmed Contempt at Malaparte’s house at Capri.

To lose Ukraine, to carve away that part of the Slavic world, would be an historic territorial loss for Russia. Putin wants and needs Ukraine for his new alliance of former Soviet republics. The US and the EU want Ukraine for NATO bases, and to serve as part of a new policy of containment of Russia, with its massive reserves of natural gas that make the country a major “contendah” in global commerce and currency wars. This is real politik at work, and the results are malodorous. Ukraine seems caught between a rock and a hard place, between two different crime syndicates, one American, the other Russian, each of them making offers that if refused guarantee further destabilization and possibly a civil war.

Kaputt, a very impressive work, brings its author to approximately the same view of the species and its alleged Creator as is outlined by Stevie Smith in the previous post.

At the time of the events narrated in Kaputt, Malaparte was working as a war correspondent on the Eastern Front for Corriere della Sera.

There can be little doubt that Malaparte saw a great deal, and made up a good bit more.

His news dispatches from the front, while beautifully writ (they are collected the The Volga Rises in Europe, 1943), do not expand and deepen the poetic mythology of the Decline of the West in anything like the way Kaputt manages, in virtually every sentence, to do.

I've posted a number of excerpts.

Two of the most popular, over time, have been this one and this one.

And meanwhile, back at the current events ranch, the world-upside-down quality of the images of the day of mass cameraphone tourism at the palace of the vanished President of the Ukraine did put one in mind of Bunuel.

A day out at the Ukrainian President's Palace (22 February 2014)

Hazen mentions the Godard film, which he and I will have remembered.

The Casa Malaparte on the rocky isle of Lipari, along with its owner, are pictured here.

The house and its famous 99 steps and legendary inaccessibility, along with several major archaic, modern and postmodern archetypes, are featured in this rare and extremely interesting doc on the making of Le Mepris (1963).

And finally, on Malaparte and his haters, an interesting piece:

Why everyone hates Malaparte: Adam Thirlwell, Guardian, 27 February 2009

Rarely mentioned even by the haters, as it is so apparently bewildering, is the confusing fact that, dying of lung cancer, Malaparte willed his earthly estate to Chairman Mao.

Thank you for the additional Malaparte information, including the Chairman Mao bequest. Did Mao actually take ownership of the estate? If so, wow and ?

I mean, that seems to be such a waste when he undoubtedly knew people who needed and could make better use of the assets.

I've finally ordered a copy of Kaputt.

"saw a great deal, and made up a good bit more" -- That's great.

Curtis

Curtis,

The ideological itinerary of Malaparte is not easy to fathom. After the American advance into Italy in November 1943, he spent two and a half years as a liaison officer for American High Command. When he left the services of the American occupation force, he joined the Italian Communist Party. He later became intrigued with Mao, went to China (where his incipient lung cancer was casually diagnosed as "a little bug"); and in the end received Last Rites in the Catholic Church.

Something tells me Mao was never aware of this curious late convert; certainly, having got on Mussolini's nerves, Malaparte would have managed the same with Mao given half a chance; and I can promise you Mao never made it up those 99 steps to take possession of Malaparte's impossible dream house.

(Being now permanently housebound due to a faulty hip joint, that proverbial codger's last straw, I'm moved to sympathy for Brigitte Bardot, re. her having been made to repeatedly run up those steps at the behest of that unsavory-looking little French director; on top of which there was that extremely uncomfortable-looking scene of flapping about naked in that very cold water; now she's got a permanently destroyed hip, can't enjoy life at all, and I don't care how rich she may be, I feel for her... on top of which she was actually upstaged in the film by the real star, Malaparte's crazy house.)

In any case, that famous bequest would have very likely been of a piece with everything else Malaparte did for public record: unpredictable, paratactic in the extreme, largely symbolic, highly theatrical.

But what I keep thinking about now, looking at the confusion of news from the Ukraine, is the remarkable clarity Malaparte brought to the chaos of history; both the hallucinated poetic sort of clarity we find in Kaputt, and the more subdued and grave sort of clarity we find in the dispatches from the Eastern Front for Corriere della Sera, collected in The Volga Rises in Europe.

History is read through history, turning into myth, and fate recognised as real through the eerie accumulation of palpable evidences of fate playing itself out. Here is Malaparte's journalistic picture of a German convoy en route from Greece to the Ukraine:

"Instinctively one knew that beneath the mask of the dust the soldiers' faces were scorched by the sun, pinched by the Greek wind. The men sat in strangely stiff attitudes; they had the appearance of statues. They were so white with dust that they looked as if they were made of marble. One of them had an owl, a live owl, perched on his fist... the bird undoubtedly came from the Acropolis, it was one of those owls who hoot at night among the marble columns of the Parthenon."

Thanks for the additional information, the excellent mini-review of Contempt and thoughts on Brigitte Bardot, which reflects feelings I share. That last Malaparte excerpt is really stunning. I received an email saying that Kaputt was on its way. And speaking of steep stone steps, roof slates, etc., I've been reading and re-reading slowly The Slide Area and enjoying it so much. Curtis

Malaparte's a fine example of the Honest Charlatan; the truth often shows up best in their work.

This post could stand as a sequel to Klimov's "Come and See".

Great film, that Klimov.

Eyes not working very well, I leapt to the errant conclusion you'd invented a clever oxymoron -- the Honest Christian!

The Lying Charlatans so abound nowadays... it's almost tempting to say they built the platform which has made this exchange possible, and could at a whim and in an instant snatch it away, after the fashion inculcated at the Lying Charlatan Academy.

And by the by, talking of film, the one Malaparte made -- wrote, directed, scored -- is, typically, a fascinating one-off.

A bit of it here:

Malaparte: Il Cristo Proibito/The Forbidden Christ (1951)

The film was a winner at the Berlin Film Festival, and two years later was nominated for foreign-film awards after its American release under the title Strange Deception.

The story, as always with Malaparte, is an oblique reflection of personal experience and concerns with loyalty, national identity, betrayal (a war veteran returns to his village to avenge the death of his brother, killed by the Germans).

I now have the Arlington, VA public library's copy of Kaputt in my possession - from the look of it (a pristine paperback, the 4th printing of the NYRB edition) I may be the first one to check it out. It is shelved as "history", not among the novels.

Well, bent truth may not be truer than straight fiction, but at least it's stranger -- and in that respect closer to reality, which is never quite strange enough, nor fictional at all.

These things, of course, are always down to the writer. Céline's proposition, that the writer performs a subtle transformation, so that the straight stick will appear bent when dipped in water, might perhaps apply.

Post a Comment