Tulsa Race Riots 1921: photo by naerae, 22 May 2011

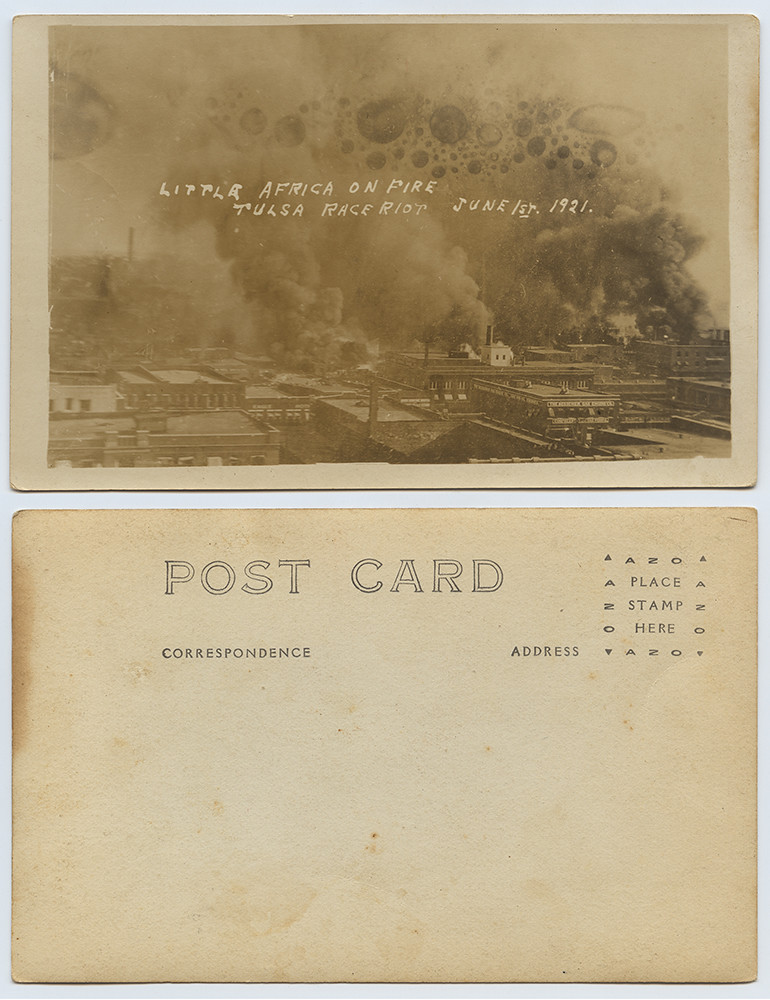

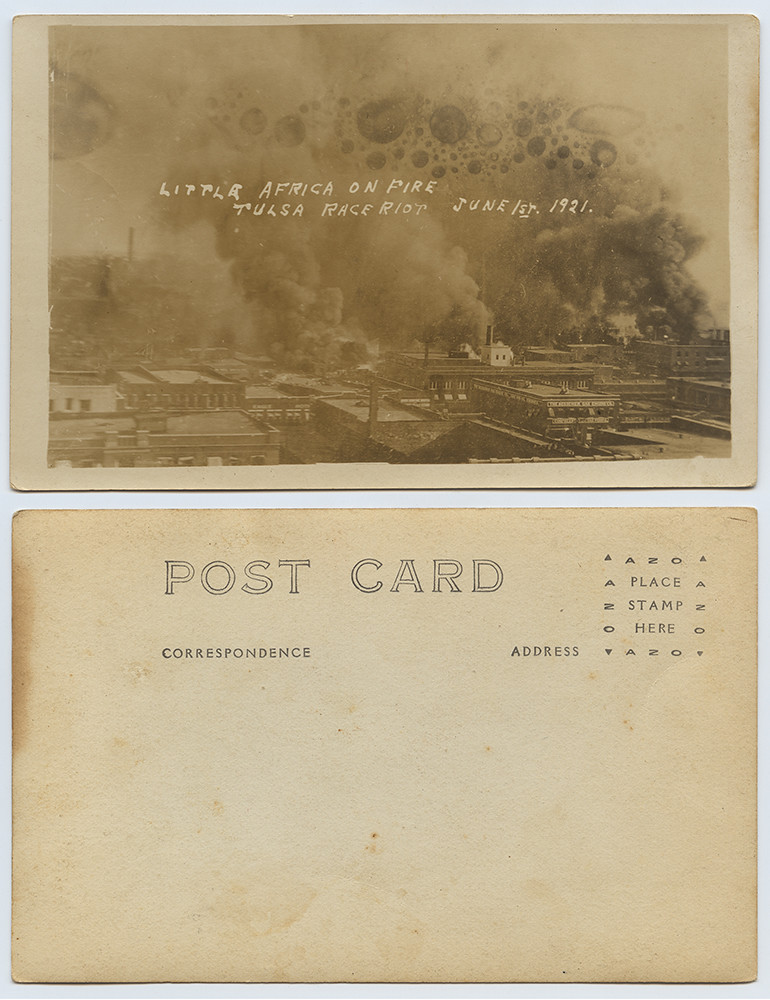

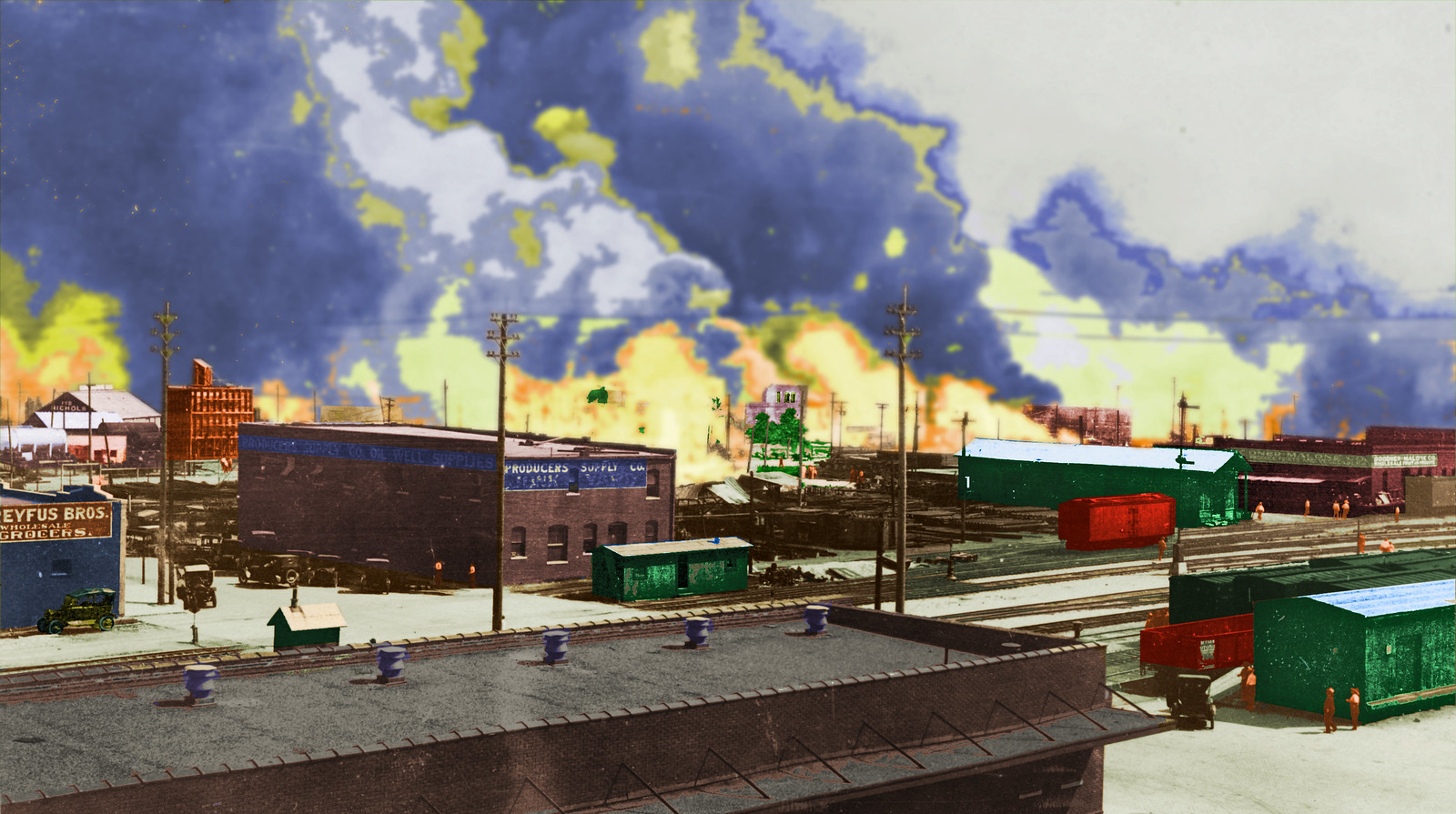

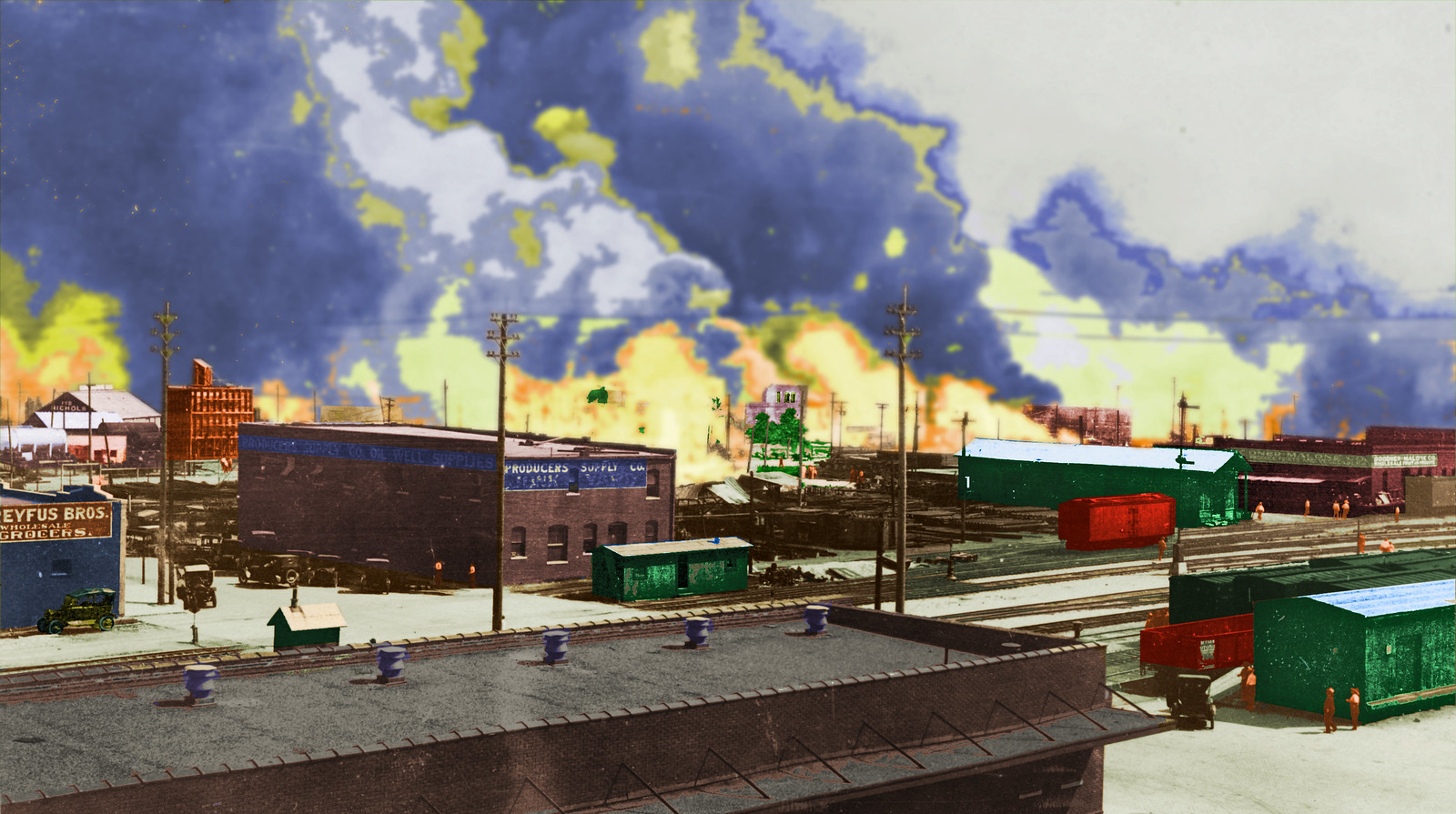

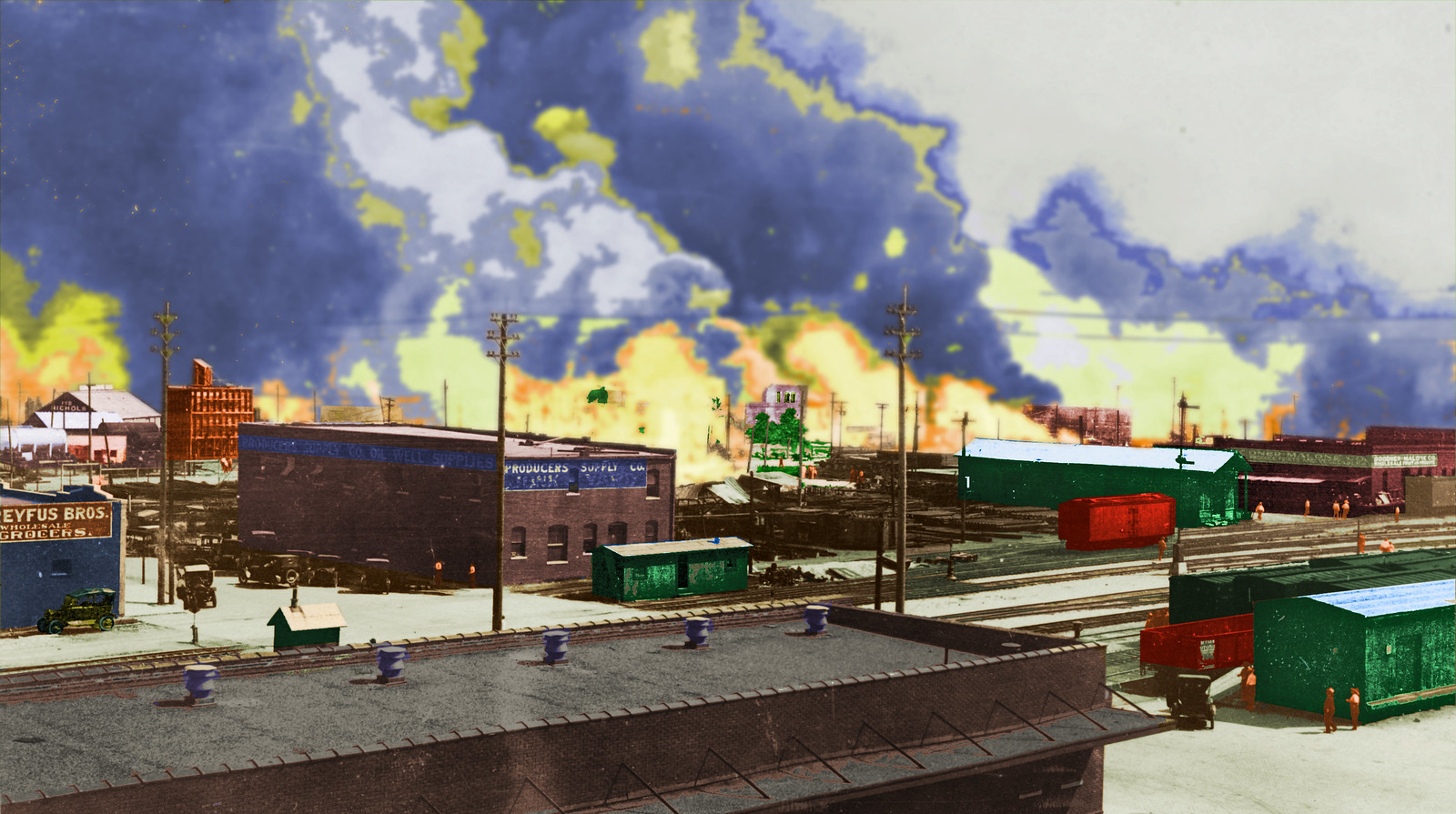

Little Africa on Fire, Tulsa Race Riot, June 1st, 1921 (Greenwood District, Tulsa, Oklahoma): photographer unknown, 1 June 1921 (De Golyer Library, Southern Methodist University)

![Burning of Church where Amunition [sic] Was Stored - During Tulsa Race Riot, 6-1-21 | by SMU Libraries Digital Collections](https://c1.staticflickr.com/3/2907/14389841381_76e95fb738_b.jpg)

![Chared [sic] Negro - Killed in Tulsa Riot, 6-1-1921 | by SMU Libraries Digital Collections](https://c1.staticflickr.com/4/3886/14391369732_661237d849_b.jpg)

Char[r]ed Negro Killed in Tulsa Riot, 6-1-1921 (Greenwood District, Tulsa, Oklahoma): photographer unknown, 1 June 1921 (De Golyer Library, Southern Methodist University)

Negro Slain in Tulsa Riot, 6-1-1921 (Greenwood District, Tulsa, Oklahoma): photographer unknown, 1 June 1921 (De Golyer Library, Southern Methodist University)

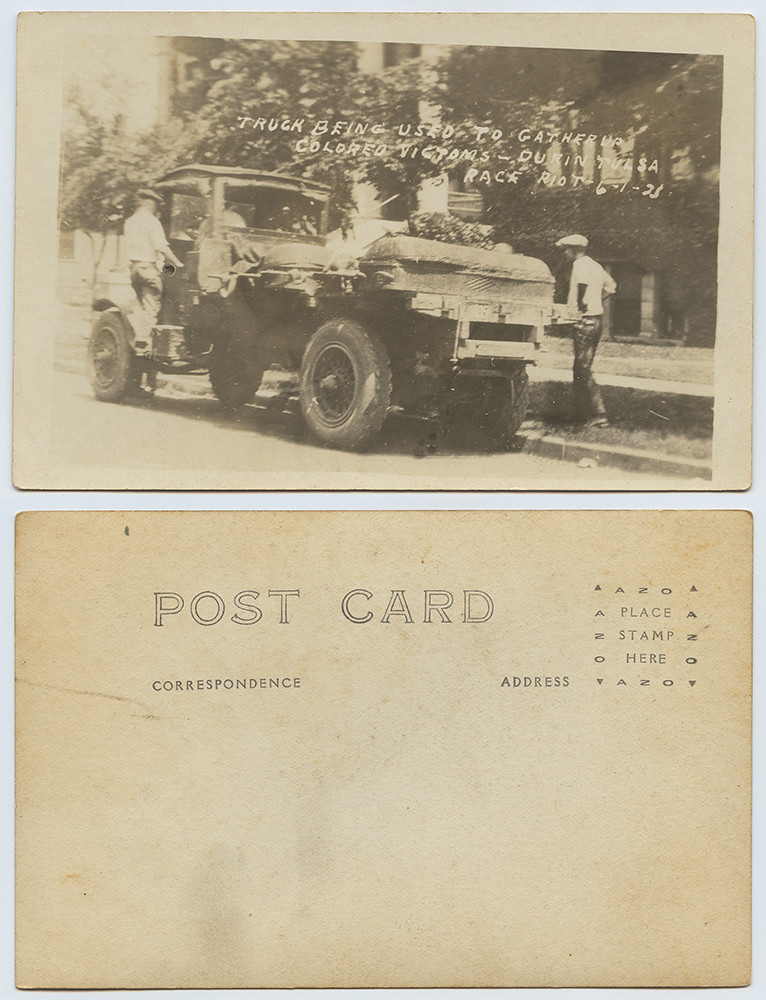

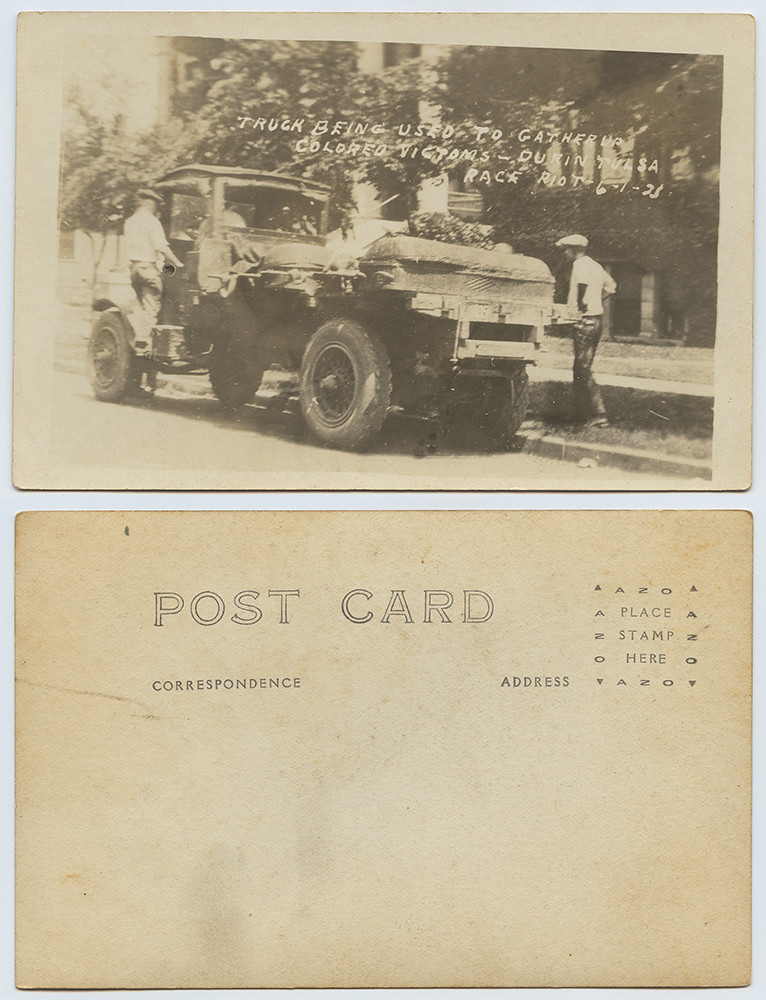

Truck Being Used to Gather up Colored Victims - During Tulsa Race Riot, 6-1-21 (Greenwood District, Tulsa, Oklahoma): photographer unknown, 1 June 1921 (De Golyer Library, Southern Methodist University)

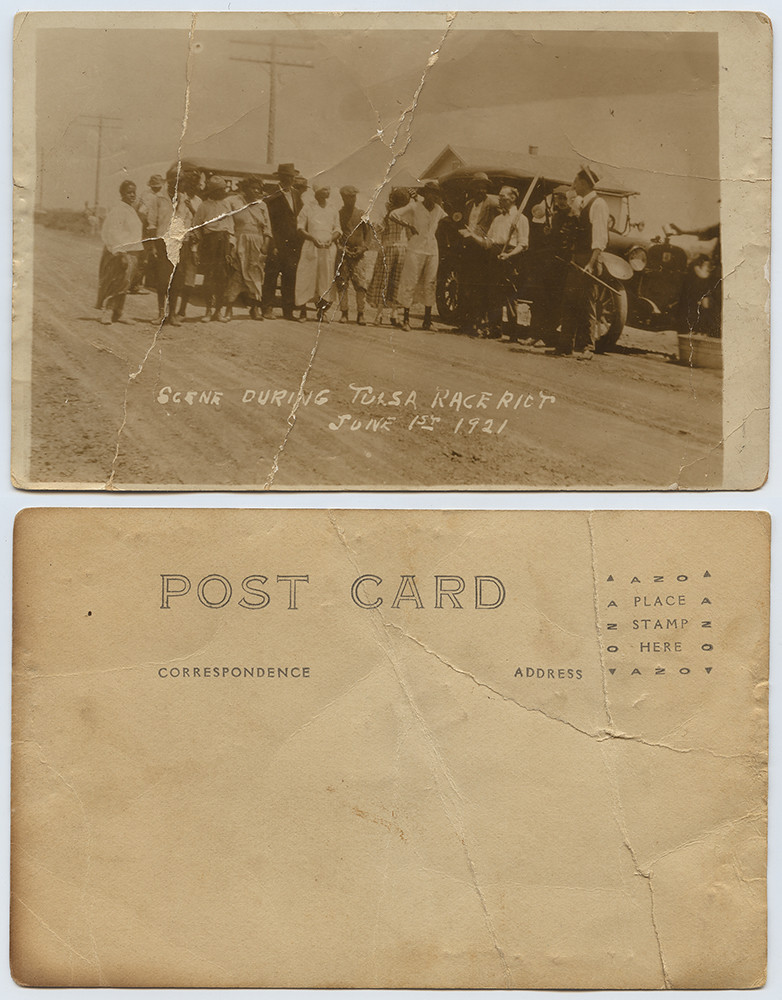

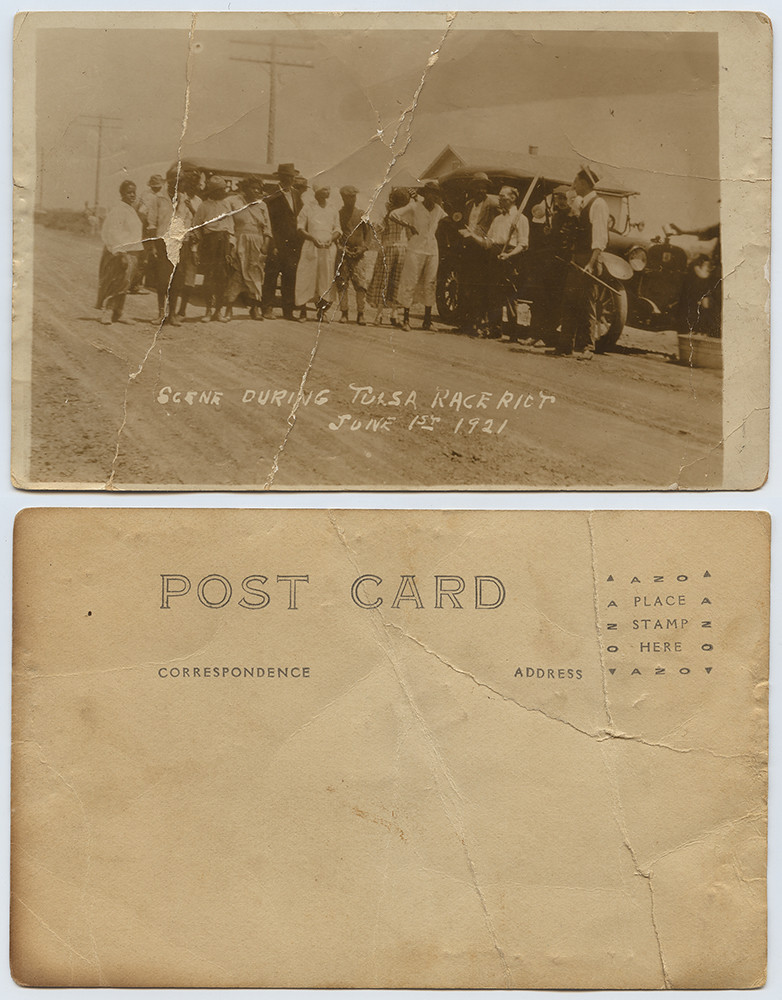

Scene During Tulsa Race Riot, June 1st, 1921 (Greenwood District, Tulsa, Oklahoma): photographer unknown, 1 June 1921 (De Golyer Library, Southern Methodist University)

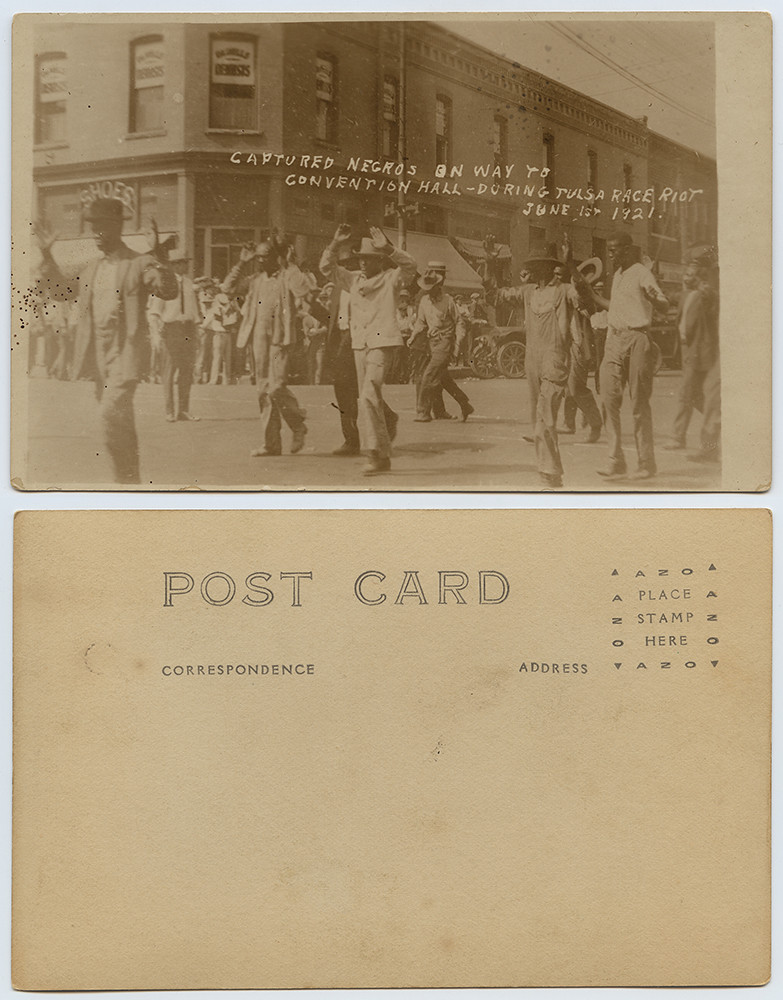

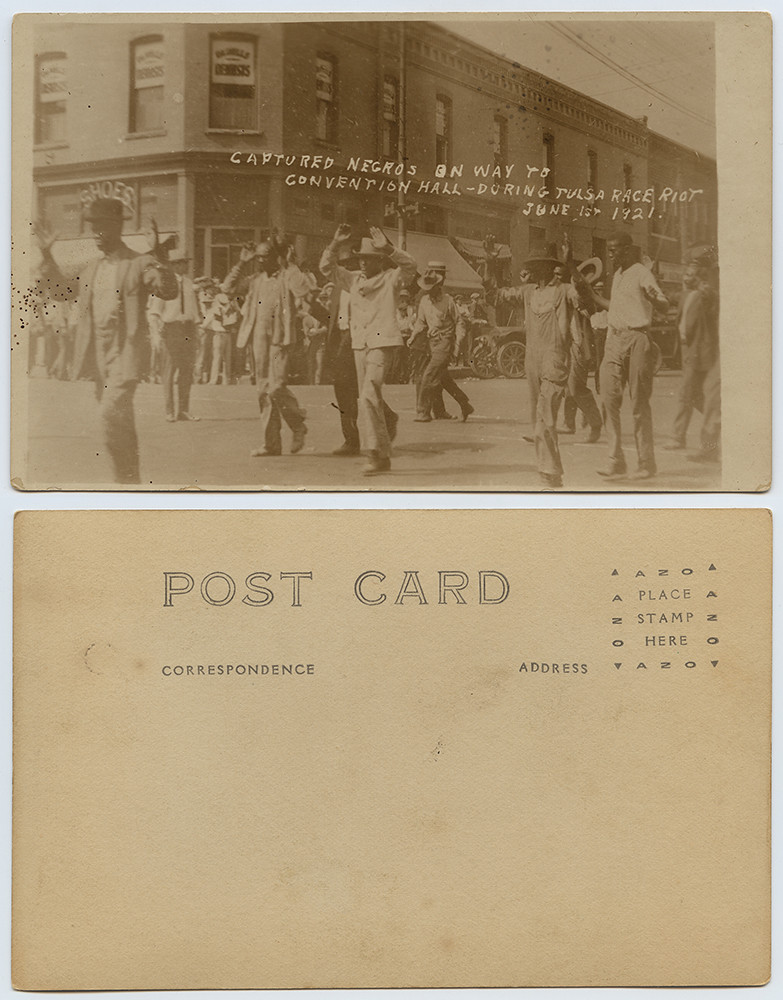

Captured Negros on Way to Convention Hall - During Tulsa Race Riot, June 1st, 1921 (Greenwood District, Tulsa, Oklahoma): photographer unknown, 1 June 1921 (De Golyer Library, Southern Methodist University

Tulsa Race Riot, June 1st, 1921. Scene at Convention Hall. (Greenwood District, Tulsa, Oklahoma): photographer unknown, 1 June 1921 (De Golyer Library, Southern Methodist University)

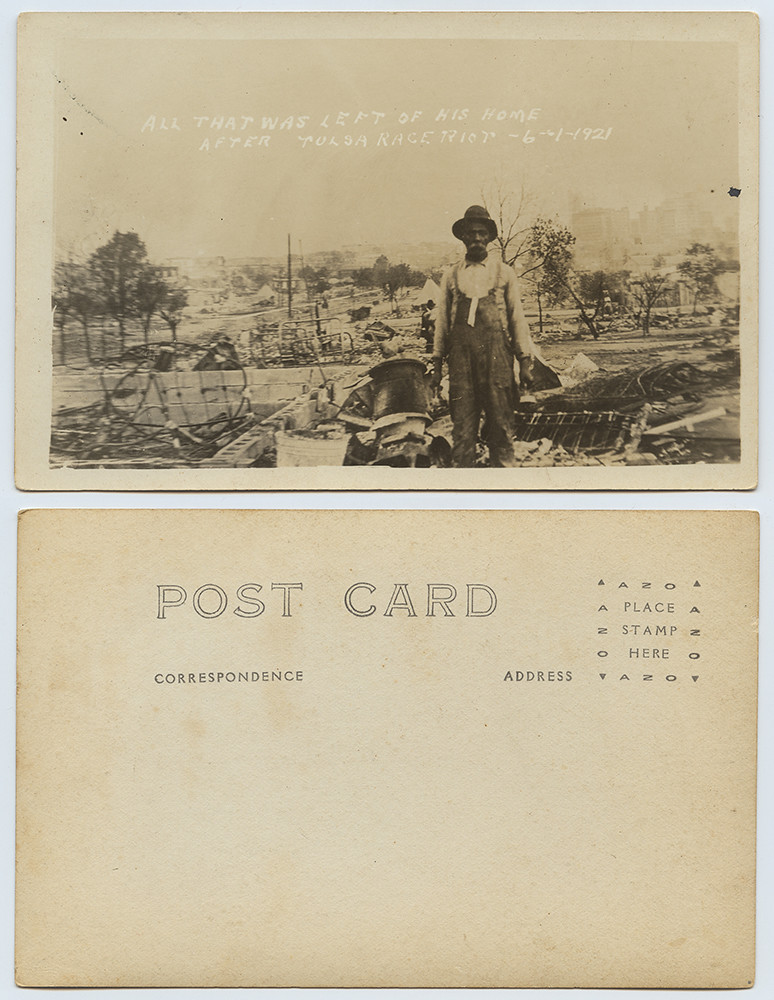

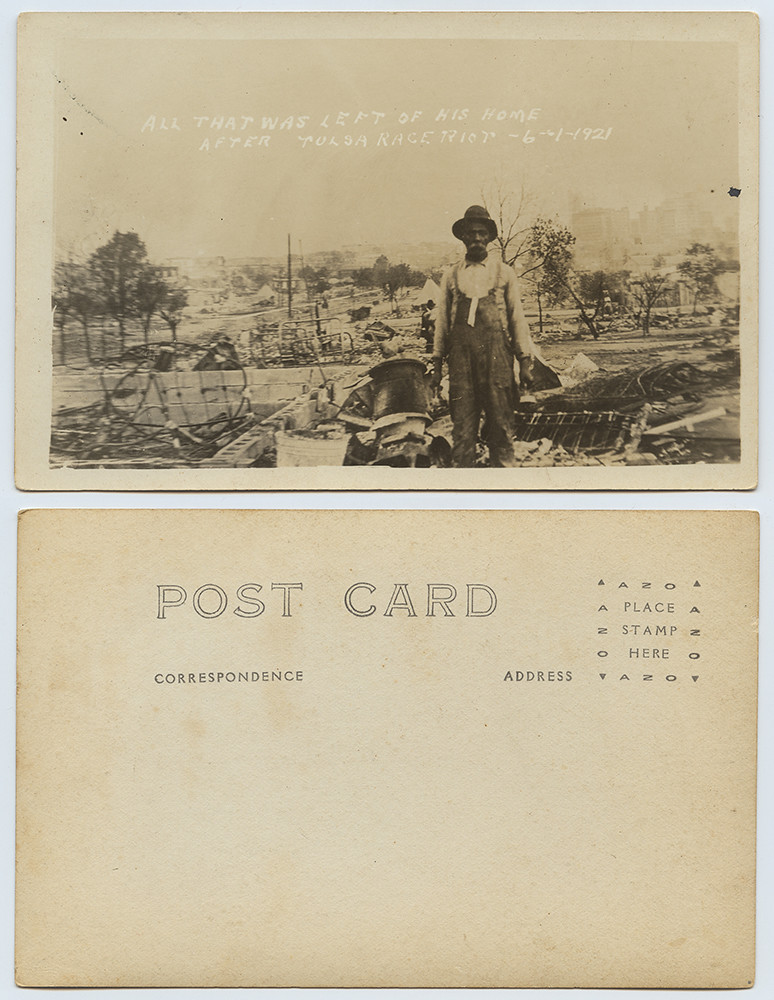

All That Was Left of His Home after the Tulsa Race Riot, 6-1-1921. (Greenwood District, Tulsa, Oklahoma): photographer unknown, 1 June 1921 (De Golyer Library, Southern Methodist University)

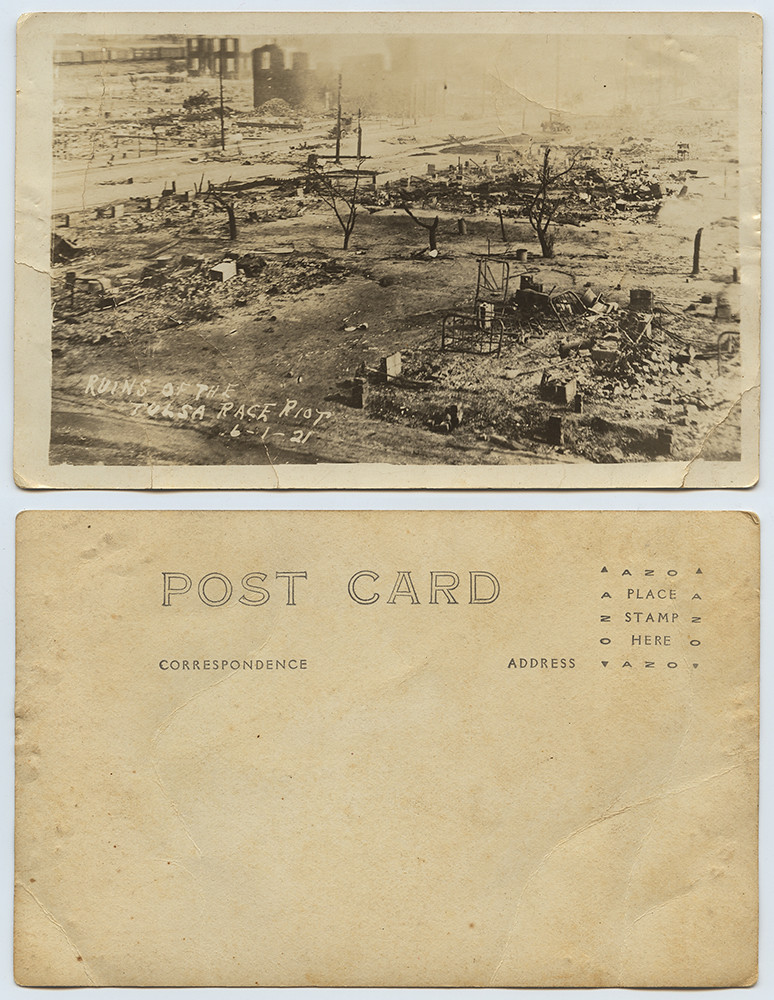

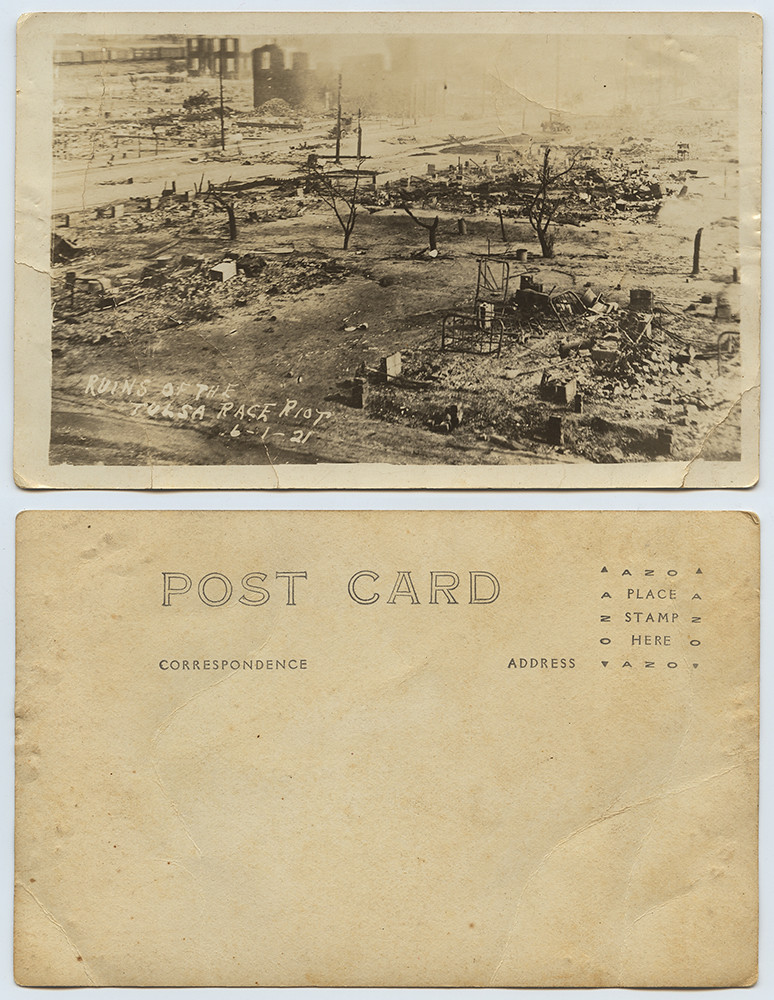

Ruins of the Tulsa Race Riot, 6-1-21 (Greenwood District, Tulsa, Oklahoma): photographer unknown, 1 June 1921 (De Golyer Library, Southern Methodist University)

Ruins of the Tulsa Race Riot, 6-1-21 (Greenwood District, Tulsa, Oklahoma): photographer unknown, 1 June 1921 (De Golyer Library, Southern Methodist University)

Ron Padgett: Tulsa Race Riots, 1921

Dick

Rowland stepped on Sarah Page’s foot

and she

lets out a scream.

Rowland, a

19-year-old bootblack,

flees the

elevator. Sarah Page, a 17-year-old part-time

elevator operator

in the Drexel Building

and

divorcée attending business college,

tells those

who rush to her aid that

he had

assaulted her.

Later that

afternoon two black police officers

arrest

Rowland at his home and take him

first to

the City Jail, then the County Jail.

That

evening’s Tulsa Tribune carries a small story

of the

alleged assault, and rumors of rape

spread

through town. By 4 p.m.

Commissioner

of Police J. M. Adkinson reports to Sheriff McCullough

that

there’s talk of lynching Rowland.

Others

confirm this report. Rumor of a lynching

reaches

“Little Africa,” where Tulsa’s 15,000 Negroes live.

Blacks

phone Sheriff McCullough to offer their services

to protect

Rowland from a lynch mob.

(Less than

a year before, in July of 1920,

Roy Belton,

a white man accused of murdering a cab driver,

was taken

from the Tulsa County Jail and lynched.

Witnesses

stated that local police officers

had

directed traffic at the lynching. The presence of a strong

and active

Klan in Tulsa added to the fear of a lynching.)

By 9 p.m.

about 400 white men have gathered outside the jail.

At 9:15

word reaches Little Africa

that the

mob had stormed the jail.

About 25

armed blacks drive to the jail and find

this rumor

to be untrue. They leave,

but soon

return with about 50 more armed blacks.

Sheriff

McCullough persuades them to leave

and a white

man tries to disarm a black.

A shot is

fired.

According

to the sheriff, “All hell breaks loose,”

firing from

both sides. Twelve fall dead,

2 black and

10 white.

Pitched and

running gun battles rage

around the

County Jail at Sixth and Boulder

and spread

from there. Whites break into

pawnshops,

hardware and sporting goods stores

to loot for

guns, ammunition and what-have-you.

The

fighting continues, groups of men surging through the streets,

excited,

angry and terrified, unreal.

By midnight

the blacks are forced to fall back

to Little

Africa. One-half block (North Cincinnati

between

Archer and the Frisco Railroad)

composed of

Negro pool halls, whorehouses, and restaurants

bursts into

flame. The blacks fall further back,

as far as

North Greenwood, the main business street of Little Africa.

The

fighting abates somewhat during the early morning hours

of

Wednesday, June 1st, but sporadic shots are heard

throughout

the night. The Final edition of the Tulsa World proclaims,

“Two Whites

Dead in Race Riot.” An Extra edition appears with

“New

Battles Now In Progress.” About 5 a.m.

10,000

white men (and Mexicans) assault Little Africa—

the total

white population of Tulsa is 57,000, 7,000

of whom

were in uniform for World War I—using small arms,

rifles,

shotguns, machine guns, and 6 airplanes

for

reconnaissance. The World brings out a Second Extra!

“Many More

Whites Are Shot.” By this time

many blacks

have fled town or are in hiding

with their

white employers. The white army

rolls

through “Niggertown,” killing the black men they see,

looting

houses and businesses and dousing them with kerosene.

One

eyewitness said, “Cars began to drive slowly

along our

street. Cars driven by the sort of men

who wear

their caps backward, the visors down their necks.”

The Fire

Department and National Guard are powerless

against the

mob. The fires rage all morning:

800 stores

and homes burned to the ground,

the

business district of Little Africa completely destroyed.

Later that

morning the last black stronghold,

the

40-day-old Mount Zion Baptist Church,

is overrun

and burned to the ground.

At noon

martial law is declared. “State Troops

In Charge,”

declares the World in its Third Extra.

National

Guard reinforcements arrive

from

Oklahoma City, Muskogee, Bartlesville, and Wagoner.

The Guard

barricades Little Africa, disarms

blacks and

whites, and herds blacks into compounds;

by evening

there are 6,000 of them

in

Convention Hall, McNulty ballpark at 11th and Elgin,

and out at

the County Fair Grounds. Dr. A. C. Jackson,

a highly

respected black physician

who had

defended his home and family with a rifle,

surrenders

to the Guard and is conducted to an internment camp;

on the way

he is shot and killed by a sniper.

The Frisco

Railroad removes its porters from trains

to Tulsa,

while passenger trains leaving town

are jammed

with blacks. Others leave by car or on foot,

some stay

in hiding up in the Osage Hills.

Civic

groups come to the aid of the homeless:

Red Cross,

Humane Society, the YMCA, and YWCA,

with food,

clothing, medical attention, and information.

The Tulsa Tribune

comes out with a strong editorial

condemning

the lawless element, white and black,

but

articles convey an undertow of public opinion:

“Martial

Law Halts Race War” “Nine Whites and 68 Blacks

Slain in

Race War” “Trains Held Up; Negroes Ordered Off”

“White

Woman Shot 6 Times By Sniper” “Barney Cleaver,

Negro

Officer, Remains On Duty” “Civic Workers Care

For Negroes

Held In Concentration Camps” “Girl Attacked

By Negro

Not At Home Today” “Fire Fighters Are Helpless;

Flames

Raging” “Blacks Carry Belongings As They Vacate.”

One story

relates how an old black woman

had given

her “Bible records” to a National Guardsman.

The next

morning the exaggerated headline reads, “Dead

Estimated

At 100; City Is Quiet.” Blacks are slowly released from camps

if their employers

vouch for them, and they wear

yellow

armbands to signify their harmlessness.

The city

promises reparations for damages.

A Board of

Estimates is formed.

The

responsible white community is shocked, ashamed, and angry.

On Friday

martial law is lifted at 3 p.m.

One hundred

members of the American Legion are sworn in

as special

police officers to keep the peace.

There are

rumors of truckloads of black bodies

dumped in

the Arkansas River.

A grand

jury is to be called to “probe the rioting.”

The World

carries an article in which

“Negro

Deputy Sheriff Blames Black Dope-Head

For

Inciting His Race Into Rioting Here.” Barney

Cleaver

describes Will Robinson not only as a “dope-head”

but also as

an “all-round bad Negro.”

A city

board moves to rezone the area near the Frisco tracks

where black

families had lived,

changing it

into an industrial and warehouse area

and

forming, in effect, a wall between white and black communities.

The new

“Niggertown” is to be rebuilt, to have, in fact,

its own

police station (until 1945).

Many blacks

have fled Tulsa forever:

young

hotheads and “radicals” on one side

and

professional people, community builders on the other.

On June 5th

the flood in Pueblo, Colorado

is splashed

across the headlines.

The Tribune

will not rehash the story of the race riots

for the

next fifty years.

Ron Padgett: from Radio, in Toujours l'amour (1976)

Little Africa on Fire, Tulsa Race Riot, June 1st, 1921 (Greenwood District, Tulsa, Oklahoma): photographer unknown, 1 June 1921 (De Golyer Library, Southern Methodist University)

![Burning of Church where Amunition [sic] Was Stored - During Tulsa Race Riot, 6-1-21 | by SMU Libraries Digital Collections](https://c1.staticflickr.com/3/2907/14389841381_76e95fb738_b.jpg)

![Chared [sic] Negro - Killed in Tulsa Riot, 6-1-1921 | by SMU Libraries Digital Collections](https://c1.staticflickr.com/4/3886/14391369732_661237d849_b.jpg)

Char[r]ed Negro Killed in Tulsa Riot, 6-1-1921 (Greenwood District, Tulsa, Oklahoma): photographer unknown, 1 June 1921 (De Golyer Library, Southern Methodist University)

Negro Slain in Tulsa Riot, 6-1-1921 (Greenwood District, Tulsa, Oklahoma): photographer unknown, 1 June 1921 (De Golyer Library, Southern Methodist University)

Truck Being Used to Gather up Colored Victims - During Tulsa Race Riot, 6-1-21 (Greenwood District, Tulsa, Oklahoma): photographer unknown, 1 June 1921 (De Golyer Library, Southern Methodist University)

Scene During Tulsa Race Riot, June 1st, 1921 (Greenwood District, Tulsa, Oklahoma): photographer unknown, 1 June 1921 (De Golyer Library, Southern Methodist University)

Captured Negros on Way to Convention Hall - During Tulsa Race Riot, June 1st, 1921 (Greenwood District, Tulsa, Oklahoma): photographer unknown, 1 June 1921 (De Golyer Library, Southern Methodist University

Tulsa Race Riot, June 1st, 1921. Scene at Convention Hall. (Greenwood District, Tulsa, Oklahoma): photographer unknown, 1 June 1921 (De Golyer Library, Southern Methodist University)

All That Was Left of His Home after the Tulsa Race Riot, 6-1-1921. (Greenwood District, Tulsa, Oklahoma): photographer unknown, 1 June 1921 (De Golyer Library, Southern Methodist University)

Ruins of the Tulsa Race Riot, 6-1-21 (Greenwood District, Tulsa, Oklahoma): photographer unknown, 1 June 1921 (De Golyer Library, Southern Methodist University)

Ruins of the Tulsa Race Riot, 6-1-21 (Greenwood District, Tulsa, Oklahoma): photographer unknown, 1 June 1921 (De Golyer Library, Southern Methodist University)

Black Wall Street | This is the historic Greenwood district of Tulsa, Oklahoma. Known as Black Wall Street, this is the site of the Tulsa race riots of 1921. Thirty five city blocks were destroyed, and up to 300 dead resulted after the worst race riot in American history. All sparked after a dubious claim of rape: photo by Victor Hamberlin, 1 January 2017

Black Wall Street | This is the historic Greenwood district of Tulsa, Oklahoma. Known as Black Wall Street, this is the site of the Tulsa race riots of 1921. Thirty five city blocks were destroyed, and up to 300 dead resulted after the worst race riot in American history. All sparked after a dubious claim of rape: photo by Victor Hamberlin, 1 January 2017

Black Wall Street | This is the historic Greenwood district of Tulsa, Oklahoma. Known as Black Wall Street, this is the site of the Tulsa race riots of 1921. Thirty five city blocks were destroyed, and up to 300 dead resulted after the worst race riot in American history. All sparked after a dubious claim of rape: photo by Victor Hamberlin, 1 January 2017

Colorized image from the Tulsa Race Riot. | The major fire in the center behind the Producers Supply Company

is the Midway Hotel in flames. The building behind it that you can see

is the Gurley Building burning. The flames to the right are from the

Williams Building. The as yet unburned building behind the building

behind the red train car is the Woods building at the corner of

Greenwood and Archer. Based on shadows this was taken about 8 in the

morning. Original photographer is unknown. Original photo

is 1989-004-5-28, McFarlin Library. Department of Special Collections

and University Archives, The University of Tulsa. Used with permission.: photo by Marc Carlson, 15 June 2012

Colorized image from the Tulsa Race Riot. | The major firein the center behind the Producers Supply Company

is the Midway Hotel in flames. The building behind it that you can see

is the Gurley Building burning. The flames to the right are from the

Williams Building. The as yet unburned building behind the building

behind the red train car is the Woods building at the corner of

Greenwood and Archer. Based on shadows this was taken about 8 in the

morning. Original photographer is unknown. Original photo

is 1989-004-5-28, McFarlin Library. Department of Special Collections

and University Archives, The University of Tulsa. Used with permission.: photo by Marc Carlson, 15 June 2012

Colorized image from the Tulsa Race Riot. | The major firein the center behind the Producers Supply Company

is the Midway Hotel in flames. The building behind it that you can see

is the Gurley Building burning. The flames to the right are from the

Williams Building. The as yet unburned building behind the building

behind the red train car is the Woods building at the corner of

Greenwood and Archer. Based on shadows this was taken about 8 in the

morning. Original photographer is unknown. Original photo

is 1989-004-5-28, McFarlin Library. Department of Special Collections

and University Archives, The University of Tulsa. Used with permission.: photo by Marc Carlson, 15 June 2012

Canned Meats | In our canned food aisle [Collinsville, OK]: photo by Wade Harris, 23 May 2007

tarboat (2008): pig's feet are not something that appear in our local supermarket!

Wade Harris (2008): Tarboat: I worked in this store as an assistant manager twice, spaced

about two years apart, and I never did see anybody actually buy any

pig's feet. But...they seem to last forever so as far as I know those

have been the same jars all during that time.

Barbed Wire Around Swimming Pool | Nothing adds

to the fun and jollyment of swimming on a hot summer day like a couple

of strands of rusty barbed wire on top of the fence surrounding the pool

you're in...... [Collinsville, OK]: photo by Wade Harris, 6 March 2007

Jackie Robinson signing autographs at Braves Field, Boston, 1948: photo by Michael Ryerson, 2 August 2018

There's a bitter-sweetness about this photo, for me. The kid with his hand on Jackie's shoulder. This is happening in Boston; Jackie is with the visiting Brooklyn Dodgers; at this point, neither of the Boston major league clubs has yet fielded a black player; this will remain the case for quite a few more years to come. Yet these Boston kids are openly adoring a hero.

Jackie was often angry, with cause; everywhere he went, he had to break down walls, and there was constant resistance. His defiance shone out in his aggressive, challenging style of play. I worked at the ballparks in Chicago, so got to see quite a bit of Jackie when the Dodgers were in town. He played with an intensity and edge that went beyond mere athletic competition; he was furiously competitive; but his adversary was never anything as simple as an opposing team or player. A slow fire burned in Jackie, and there were days when it flared up into something almost like majesty.

There was the day he was on third base, and dancing, feinting, as if taunting, intentionally provoking; finally he got what he wanted, a moment's distraction on the pitcher's part; in the space of that brief pause and the long unfolding moment that followed, the world had changed; Jackie had bolted for home; there was a collectively held breath, and then Jackie was sliding home, in a sudden bright cloud of dust.

Dark rocks [California]: photo by Andrew Murr, 1 August 2018

Jackie Robinson signing autographs at Braves Field, Boston, 1948: photo by Michael Ryerson, 2 August 2018

There's a bitter-sweetness about this photo, for me. The kid with his hand on Jackie's shoulder. This is happening in Boston; Jackie is with the visiting Brooklyn Dodgers; at this point, neither of the Boston major league clubs has yet fielded a black player; this will remain the case for quite a few more years to come. Yet these Boston kids are openly adoring a hero.

Jackie was often angry, with cause; everywhere he went, he had to break down walls, and there was constant resistance. His defiance shone out in his aggressive, challenging style of play. I worked at the ballparks in Chicago, so got to see quite a bit of Jackie when the Dodgers were in town. He played with an intensity and edge that went beyond mere athletic competition; he was furiously competitive; but his adversary was never anything as simple as an opposing team or player. A slow fire burned in Jackie, and there were days when it flared up into something almost like majesty.

There was the day he was on third base, and dancing, feinting, as if taunting, intentionally provoking; finally he got what he wanted, a moment's distraction on the pitcher's part; in the space of that brief pause and the long unfolding moment that followed, the world had changed; Jackie had bolted for home; there was a collectively held breath, and then Jackie was sliding home, in a sudden bright cloud of dust.

Dark rocks [California]: photo by Andrew Murr, 1 August 2018

5 comments:

Howlin' Wolf: Smokestack Lightning (live, London 1964)

Great post, Tom. Ron's poem as reportage is stunningly effective. And Howlin' Wolf: what a formidable presence.

Many Thanks Terry. Agreed on both counts.

(I closed my eyes and imagined Wolf caught in the Burning of Little Africa.)

Jackie Robinson

Post a Comment