.

A poet departs, too soon, and there is a void that will not be filled. From somewhere deep and old the tears well up in the dark night.

When I met Jim in 1967 he was seventeen. He had been leading a triple life: high school All-American basketball star, heroin addict/street hustler, poet.

On scholarship at the elite Ivy league prep academy Trinity School (alums include Humphrey Bogart, Truman Capote, Ivana Trump, Yo Yo Ma, John McEnroe, Aram Saroyan), he had shown unusual abilities on the court. He had played against the city's best (including Lew Alcindor, later Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, who had starred at Power Memorial, a school in Jim's own Inwood Park neighborhood). His skills had drawn the attention of college scouts. The turning point, according to one of his versions of the story, had come when a representative of Notre Dame took him out for dinner. Jim told the story with great good humor; the Notre Dame man had ordered a spaghetti dinner. Jim had listened politely to the man's talk of the virtues of a Notre Dame education. And then nodded out into the spaghetti.

His people were Irish Catholic. His father owned a bar. In 1995 he talked to John Stewart of Interview about his early life.

JC: ... the way I got into writing was Catholic grammar school. It was the one good thing that I got out of the nuns and Brothers that taught me...

JS: Was there ever a sense that basketball held a finite limit for you, and that writing was infinite?

JC: Well, yeah. But it wasn't that canny, actually, because I had been writing for a long time. People think that my demise in basketball was from drugs, but it wasn't. I wasn't getting high before every game. Once in a while we made the mistake of taking downers instead of ups and stuff before a game. But from the time I was eight, my whole goal was basketball. I practiced all day after school. By my junior year, though, the jock trip started running thin. This was the late '60s, and chicks wanted guys who had long hair and went to folk clubs and wrote poetry and stuff. So I started jerkin' off and hanging around the poetry scene. Instead of playing in the summer tournaments, my art teacher gave me his loft down in the Village while he went to Cape Cod for the summer. It was, like, hellza-poppin, man! I was what, sixteen? My first book of poems came out that summer, just a small book - like thirty pages. I made up my mind right then that I was going to be a poet. No matter how difficult it was to live or anything, that's what I was going to do. And that sort of opened me up in a whole different way, Because I was always kind of withdrawn and looking at things from a distance. I told Leonardo [DiCaprio, in the movie based on Jim's Basketball Diaries] to lay back at certain times. When the action's really happening, of course, stealing a car or something, you're involved in it completely. But sometimes you just withdraw yourself. Because they called me Daisy, since I was always in dazes. In fact, my parents took me to doctors because they thought I had some form of epilepsy. But it was determined that I just had a vivid imagination. I'd just go off. Even before I was into writing, I'd be waiting for a three-on-three game to end and they would have to shake me. But when I was into writing, I was not only thinking about strange things; I was formulating them on the page as well.

JS: And then you went on to become a rock 'n' roll performer. How did those two things connect?

JC: I remember reading The Time of the Assassins, which is Henry Miller's book examining Rimbaud's life and work - although he's really examining his own life and work. But it's a genius book, and he talks about, "Where are the poets today?" I mean, the nobility of poetry is missing. In the neighborhood where I grew up, you couldn't tell people that you were writing poetry, man. I mean, you were considered a sissy if you wrote poems, for God's sake. The mailman for my building hung out in my father's bar, and one day when he was half in the bag he starts asking my father, "What's happening with your son? I used to read about him in the papers making the all-city team and shit. Now he's getting all these poetry magazines in the mail. He's got long hair. What the hell's wrong with him?" My father comes home. I'm like, "Hey, Dad, how you doin'?" Boom! "Get a hair-cut! What's with this poetry shit?"

Jim had by that time already begun haunting the Poetry Project at St. Mark's in the Bowery Church. He loved the poetry of Frank O'Hara, and writing under a rush of Frank's influence, at seventeen produced his own first slim chapbook, Organic Trains. Ted Berrigan had taken Jim under his wing. Poetry not basketball was where Jim wanted to go in his life.

A sweet, shy, gentle, lovely good-humored young man, gracious to a fault. We were soon friends. He gave me his phone number and asked that I give him a call any time. I rang the number and a young woman's voice came on, saying Jim wasn't home. I later asked if that had been his girlfriend. "No," he said with his customary shy twinkle, "my mom."

I was dazzled by the promise of unusual gifts evident in Jim's poetry and soon began putting his poems in The Paris Review. Over the next few years I placed a half dozen of them there (along with, later on, an excerpt from The Basketball Diaries).

One of those Paris Review poems is in my mind tonight.

The Birth and Death of the Sun

Now the trees tempt

the young girl below them

each moves off the other's wind

endlessly, as stars from the earth,

stars from the stars.

*

In March 1968 Angelica and I got married at the Church. The day before the wedding, while we were downtown obtaining a marriage license, the junkies who lived below me in a 14th Street apartment house climbed up the fire escape and stole all our belongings that seemed of value. That night John Giorno threw a bachelor party for me at his place down on the Bowery. After our trying day, Angelica understandably did not want to stay alone in my torn-up apartment. She came along to the party and immediately went to sleep on John's bed--as is documented in photos taken at the party by Peter Schjeldahl. Peter's photos from the party show Jim, babyfaced and sweet looking, his strawberry mop tousled over his eyes, dressed up neatly in blue blazer, oxford shirt, red prep school tie. In one shot he can be seen intently studying a volume of poetry. In another he sits quietly at Ted's side as Ted, holding forth, carefully rolls a joint. Across the table is George Schneeman. John Wieners and Mike Goldberg are also in the photos. They're all gone now.

*

In another old fading photo stuck in a dusty album around here, five or six years have passed and a leaner, lanker, longer-haired Jim, now developing a craggy Prince Valiant look, is hanging out with me on Bolinas Beach. In 1973 he had come out to Bolinas to kick his heroin habit. He lived for awhile at a house downtown, under the informal protection of the ever generous Bill Berkson. There he dwelt largely unto himself, working on the long careful reconstruction of his youth that would be The Basketball Diaries. Bill regularly drove him over the hill to San Rafael, where Jim had entered a detox program.

This was the beginning of a long, deep, isolating struggle for him.

When the always variable weather allowed there was in those years a daily pick-up basketball game at the outdoor court in the playground of Bolinas School. I was guilty of forever attempting to get the reclusive Jim to come out to join us. Only on rare occasions did he agree, and then, as I recall clearly, in an entirely dispirited and lackadaisical fashion. It was like asking a great violinist to take up a plastic ukulele. He would stand disinterestedly at the top of the key, doing his best to seem invisible so as avoid the ball. If you insisted on passing it to him, however, there was always a moment or two of casual miracle work that told you of the quality of his skill in this sport of his youth. Always completely expressionless. For Jim this was an old familiar zone of proper action. A quick move. A silky smooth long jumper grabbing nothing but the tattered net on its true way through the hoop. Or a brilliant nonchalant no-look pass, flicked without effort into the hands of the unmarked man.

Into

even the

perfect

jumpshot

can't match

the perfect

pass

for insight

into the

mysterious

*

A little later Jim found a place of his own, a small cottage in a eucalyptus grove at the foot of Mesa Road. He was then working on his Forced Entries diaries and the poems of The Book of Nods. Jim was a painstaking writer who never hurried things along. In these years he became even more withdrawn, his constant companion a small terrier he called Jo'mama. Jim loved that little dog dearly, I think its company got him through the darknesses of those years of seclusion.

Lying with the Dog

My dog sleeps with me. It's nice. He lies always in the same spot, at the bottom of the bed, with his little head on my right ankle. When the weather turns cold, he simply climbs beneath the covers and pads his way to the exact same place, resting his head. Only then can I feel his fuzzy neck and chin. I've come to rely on these simple pleasures.

Last night I had a hideous nightmare. Usually I can guide my dreams, once they arise, bad or good. But there is no control when the dream takes place in the room in which I'm actually sleeping. No guiding the horror of the man standing in the corner, or emerging from the closet with luminous eyes, holding a huge syringe-like scepter, advancing at me, speaking in tongues. ("Tubalar," he says, that's the only word I can remember, "Tubalar.")

Then I can't separate the dream, can't divide it from the reality of my room. I've begun a program of detoxification, and the lower my dose of mojo juice, the more often this person invades the one sanctuary where I cannot ward off the nightmare's cunning, or control the demons. He comes in various costumes; he knows the rituals of my vulnerabilities.

But last night, as always when it happens, when I wake up in toxic sweat, sometimes dreaming, Jo'mama comes up to my face and licks, and kneels there like a sentinel. I'm open to such gushing sentiment. I welcome it. I've suppressed it for too long. I thank God for the dog... he calms me down, and that's as much as you can ask for. It surely is enough to feel free to lick him in return, before I can risk more sleep, and he goes back to my ankle and yawns as he circles once more before he rests his head there.

*

He invited me to come over to do a reading with him at the detox center in San Rafael. There he was among his company of fellow rehab souls, all lost and looking to find themselves. In one room the methadone (which Jim termed "mojo juice") was doled out from behind barred windows, in small plastic cups, mixed with orange juice. The cups had to be drained there at the window. Then came the reading.

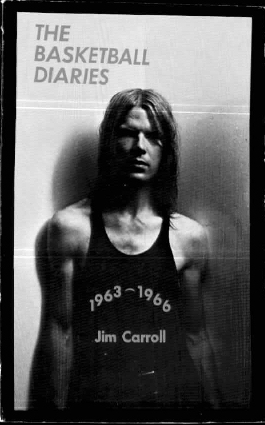

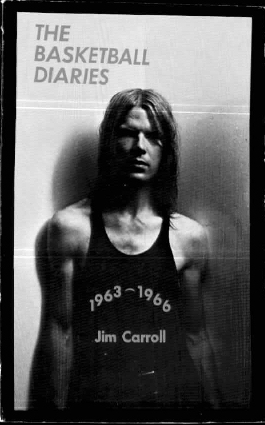

Poetry readings have never exactly been my idea of a good time. This however was the most electrifying and intense poetry reading I have ever attended. Jim read "Guitar Voodoo" from The Book of Nods. His "look" at the time was pretty much as can be seen on the cover of the original edition of the Basketball Diaries. There were about ten people in the small windowless linoleum floored institutional chamber. It was totally mesmerizing; I felt privileged, uplifted and scared. While reading Jim seemed to leave himself and become the conductor of energies from another place. I understood then that I was in the presence of a master, his powers palpable yet perhaps beyond the understanding of anyone present. The work told a tale of sexual revenge occurring in a vivid psychic dimension of superhuman electrical charge. A harrowing experience, unforgettable.

Afterward there was a workshop session with other writers from the detox program. Many were broken and down in soul, yet their readings seemed to bring them briefly to life. A woman with her arm in a cast after a dispute with her lover read a piece in which her private hells were entered. Jim gently supported her in the ensuing discussion. Here he was at home among the lost, helping as a guide whose words could be believed because he had been there, and indeed maybe dwelt there still.

In those years he mixed socially not at all. He had all but disappeared. I too had stepped away from the daily town whirl of sociality. Each day at dawn I ran down Mesa Road and out to the Olema Road, passing Jim's hermit's cabin. We saw each other and exchanged unspoken greetings, a wave, a nod. Neither of us asking more. To me he seemed then in his solitude with his demons and his angels (as I imagined them) a gaunt ascetic saint of a special order beyond the ken of the scene, in its pleasant bubble.

The Door to the Forest

for Jim

Eric Dolphy can't wake up:

the green light's still burning

by the gate. Pine cones

when stepped on by

dogs or raccoons, click

gently, like bones

into the mist, which

smells like mint; the

sounds diminish it;

the white rose

through the dropper's eye

falls; and the rain remains.

*

In 1978 Jim finally resolved to let go of The Basketball Diaries. Our neighbor Michael Wolfe of Tombouctou Books leapt at the opportunity to publish the work. I wrote an introduction in which I staged an imaginary conversation between myself and an older Arthur Rimbaud, to whom I spoke of Jim as a latterday confrere. The impulse came from Jim himself, who felt Rimbaud's work deeply and in effect channeled him in pieces like "Rimbaud's Toothache" and "Rimbaud sees the Dentist", in which he transferred his own experiences to the long dead poet. That kind of detachment came naturally to Jim.

He and Jo went on long hikes, Jim with his pilgrim's staff walking stick. The two of them climbed far up upon the sleeping flanks of the great female shaped mountain Tamalpais. I believe that despite the harsh loneliness and inner torments that were his burden in those years Jim was then finding ecstasy of a kind, in fleeting glimpses. The moments probably didn't last, but I sensed there must have been in them a shining intermittent respite from ambient pain, a kind of lapsing transcendence.

I have to reregister a room for my heart. It's been waiting a long time, somewhere outside, without so much as a whisper of protest. That abandonment wasn't just an abuse, it was a sin.

Today I went for a long walk with my dog, up to Mount Tamalpais. I watched a pumpkin spider for hours, weaving its web across a tri-pronged branch on a dead thorn bush. After watching all the insect death and escape, and the repairs that followed, I wanted to feel the web. It was nothing more than tactile curiosity. I reached out and fingered a piece, but I couldn't control my newly recovered senses. The fine tuning of my touch was off. I just couldn't gauge the resilience of the web. I was too caught up in the vibrance of the orange hump on the spider, and the silver intricacy of the weave. By the time I pulled my hand free, the whole web was torn apart. It seems the deeper I allow my perceptions to penetrate, the more ruin I leave in my wake.

I could vaguely fathom then that Jim was capable of a poet's pure wonder, the sort of thing I thought had gone out of poetry with Blake and Keats. Not until much later did I come to fully realize the quality of the poetic genius in whose presence I had been so fortunate to find myself, if only for isolated instants, as I padded along the cold asphalt in my two-dollar sneakers and he sauntered past with his stick and his little dog, giving me a wordless wink and a high sign, beneath the eucalypti, by the waters of the lagoon--all of it now drowned amid the tears of time.

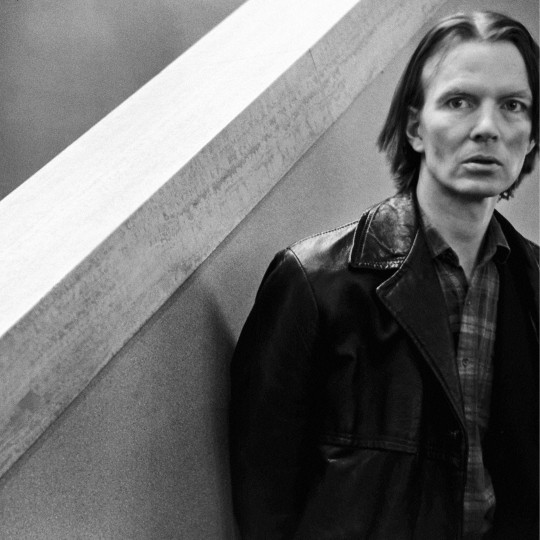

Jim Carroll, Seattle: photo by Eric Thompson, 2000

Jim Carroll: photo via catholicboy website

Fields of Sawdust (Bolinas): photo by blmurch, 2007

The Basketball Diaries (cover), 1968

Bolinas Road: photo by Agent of Orange, 2005

Lone pelican (Mt. Tamalpais, from Bolinas Beach): photo by edwinsail, 2007

Jim Carroll: The Street Side of the Game, Interview 25.4

JC: The Birth and Death of the Sun: from Living at the Movies, 1973

TC: Into: from Blue, 1974

JC: Lying with the Dog: from Forced Entries, 1987

TC: The Door to the Forest: from Blue, 1974

JC: Torn Web (extract) from Forced Entries, 1987