Horloge republicaine: clock dial of the French Revolution, from The Republican Calendar, late 18th c.: image by Kama, 2005

Pray, my dear, quoth my mother, have you not forgot to wind up the clock?Laurence Sterne: The Life and Opinions of Tristram Shandy, Gentleman, Volume I (1760), Chapter I

1 Beating the Clock

"Laurence Sterne's great invention was the novel that is completely comprised of digressions, an example followed by Diderot. The digression is a strategy for putting off the ending, a multiplying of time within the work, a perpetual evasion in flight. But flight from what? From death, of course, says Carlo Levi, in an introduction he wrote to an Italian edition of Tristram Shandy:

"'The clock is Shandy's first signal. Under its influence he is conceived and his misfortunes begin, which are one and the same with this emblem of time. Death is hidden in clocks, as Belli said; and the unhappiness of an individual life, of this fragment, this divided, disunited thing, divorced of wholeness: death, which is time, the time of individuation, of separation, the abstract time that rolls toward its end. Tristram Shandy does not want to be born, because he does not want want to die. Every means and every weapon is valid to save oneself from death and time. If a straight line is the shortest distance between two fated and inevitable points, digressions will lengthen it; and if these digressions become so complex, so tangled and tortuous, so rapid as to hide their own tracks, who knows -- perhaps death may not find us, perhaps time will lose its way, and perhaps we ourselves can remain concealed in our shifting hiding places.'"

Italo Calvino: from Quickness, in Six Proposals for the Next Millennium, 1985 (published posthumously, 1988)

2 "...a metaphysical dissertation upon the subject of duration"

Like Locke's doctrine of the association of ideas, at once foregrounded at the narrative surface of the novel and yet made the butt of endless gentle mockery, abstractions like Time and Space are treated in Tristram Shandy as ridiculous bubbles, idle play-things of the dull mind, their pseudo-serious deployment in the text repeatedly undermined by irony and a highly civilized form of wit.

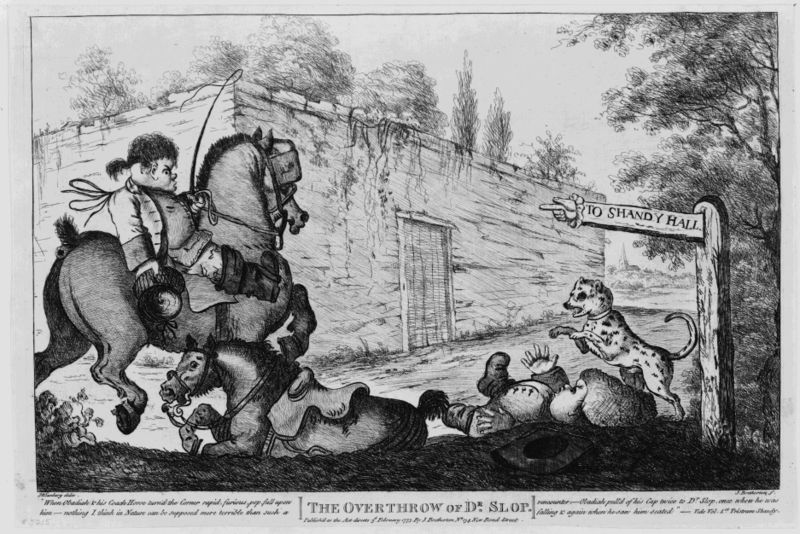

It is two hours, and ten minutes,---and no more,-----cried my father, looking at his watch, since Dr. Slop and Obadiah arrived,-----and I know not how it happens, Brother Toby,-----but to my imagination it seems almost an age.

-----Here-----pray, Sir, take hold of my cap---nay, take the bell along with it, and my pantoufles too.-----

Now, Sir, they are all at your service; and I freely make you a present of 'em, on condition you give me all your attention to this chapter.

Though my father said, 'he knew not how it happen'd,'-----yet he knew very well how it happen'd;-----and at the instant he spoke it, was pre-determined in his mind to give my uncle Toby a clear account of the matter by a metaphysical dissertation upon the subject of duration and its simple modes, in order to shew my uncle Toby by what mechanism and mensurations in the brain it came to pass, that the rapid succession of their ideas, and the eternal scampering of the discourse from one thing to another, since Dr. Slop had come into the room, had lengthened out so short a period to so inconceivable an extent.-----"I know not how it happens,"-----cried my father,-----"but it seems an age.'

—---Tis owing, entirely, quoth my uncle Toby, to the succession of our ideas.

My father, who had an itch, in common with all philosophers, of reasoning upon every thing which happened, and accounting for it too-----proposed infinite pleasure to himself in this, of the succession of ideas, and had not the least apprehension of having it snatch'd out of his hands by my uncle Toby, who (honest man!) generally took every thing as it happened;-----and who, of all things in the world, troubled his brain the least with abstruse thinking;---the ideas of time and space,-----or how we came by those ideas,-----or of what stuff they were made,---or whether they were born with us,---or we picked them up afterwards as we went along,---or whether we did it in frocks,---or not till we had got into breeches,---with a thousand other inquiries and disputes about INFINITY, PRESCIENCE, LIBERTY, NECESSITY and so forth, upon whose desperate and unconquerable theories so many fine heads have been turned and cracked,---never did my uncle Toby's the least injury at all; my father knew it,---and was no less surprized than he was disappointed, with my uncle's fortuitous solution.

Do you understand the theory of that affair? replied my father.

Not I, quoth my uncle.

-----But you have some ideas, said my father, of what you talk about?-----

No more than my horse, replied my uncle Toby.

(III.XVIII)

The central joke and symbol of Sterne's grand comic novel is the clock, which plays a role in his hero's fate from the literal moment of his conception -- an act interrupted by his mother's question to his father, "Pray, my dear,...have you not forgot to wind up the clock? (I.I)

In this initial scene, of course, as throughout his novel, Sterne is "winding up" his reader, who is habitually bound to a mortal finitude by the restrictive constraints of an iron temporality: "...in our computations of time [laments Tristram's father, a bit later on], we are so used to minutes, hours, weeks, and months-----and of clocks (I wish there was not a clock in the kingdom)…'' (III.XVIII)

Sterne contracted tuberculosis as a young man and struggled with the disease throughout his life. Though already in failing health in his mid-forties, when he began Tristram Shandy in 1658 he managed to complete the first sixteen chapters in six weeks and the first two volumes within two years, and resolved thereafter to write two volumes a year for the rest of his life. Despite the intermittent advances of his disease he kept approximately to this schedule, completing nine volumes before his death in 1768. The entire work was composed under the pressure of an acute consciousness of mortality.

The strategies of extension, elaboration, complication, equivocation, prolongation, procrastination, prevarication, teasing, lengthening, stretching-out -- the strategies, in short, which drive this most digressive of novels -- can be seen to have a common logical basis in the desire to retard an ending, not only of a novel but of its author's existence.

Here we find our author/narrator, after six weeks of composition, fourteen chapters into the affair of a character who has however not yet been born. Tongue securely in cheek, Sterne, through the voice of Tristram, supplies his impatient reader a kind of apology -- or better to say, perhaps, an apology of a very curious yet, already by this stage of the proceedings, familiar and characteristic kind.

Could a historiographer drive on his history, as a muleteer drives on his mule,—---straight forward;-----for instance, from Rome all the way to Loretto, without ever once turning his head aside, either to the right hand or to the left,---he might venture to foretell you to an hour when he should get to his journey's end;-----but the thing is, morally speaking, impossible: For, if he is a man of the least spirit, he will have fifty deviations from a straight line to make with this or that party as he goes along, which he can no ways avoid. He will have views and prospects to himself perpetually soliciting his eye, which he can no more help standing still to look at than he can fly; he will moreover have various

....Accounts to reconcile:

....Anecdotes to pick up:

... Inscriptions to make out:...

....Stories to weave in:....

....Traditions to sift:....

....Personages to call upon:

....Panegyricks to paste up at this door:

....Pasquinades at that:-----

All which both the man and his mule are quite exempt from. To sum up all; there are archives at every stage to be look'd into, and rolls, records, documents, and endless genealogies, which justice ever and anon calls him back to stay the reading of:---In short there is no end of it;-----for my own part, I declare I have been at it these six weeks, making all the speed I possibly could,—---and am not yet born:---I have just been able, and that's all, to tell you when it happen'd, but not how;---so that you see the thing is yet far from being accomplished.

(I.XIV)

By a typically Shandean irony, it is the very dilatoriness of Sterne's narrative procedure, with its seemingly infinite retardations and interruptions, pausings and turnings-aside to cast off in new directions -- “But there is a fatality attends the actions of some men: Order them as they will, they pass thro’ a certain medium which so twists and refracts them from their true directions..." (I.X) -- that seems to hold mortality at a safe remove as long as the story, through whatever ingenious trick or ruse or stratagem of suspension or delay, can be kept going.

… for I had left Death, the lord knows -----and He only---how far behind me-----"I have followed many a man thro’ France, quoth he---but never at this mettlesome rate"-----Still he followed,-----and still I fled him ----- but I fled him chearfully----still he pursued ---but like one who pursued his prey without hope-----as he lag’d, every step he lost, softened his looks-----why should I fly him at this rate?

(VII. XLII)

As Time, however Death may seem to lag, remains a wasting force, and as such drives a wing'd chariot, the narrator must achieve his necessary slowness by moving at an ever swifter pace: “-----write as I will, and rush as I may into the middle of things, [...]---I shall never overtake myself.” (IV.XIII) “Time wastes too fast: every letter I trace tells me with what rapidity Life follows my pen...” (IX.VIII)

The paradox of this unique Shandean rate of movement, a narrative development alternately almost maddeningly protracted, and then shockingly sudden and abrupt, begins to make sense when considered in light of Sterne's overall objective -- that is, never to complete things, by never coming to a full stop.

"Now I....think differently; and that so much of motion, is so much of life, and so much of joy---and that to stand still, or get on but slowly, is death and the devil-----" (VII. XIII)

And we are thus able to begin to understand that for the purposes of the writer the putting-off of tasks is not perhaps the vice it is generally regarded to be. Take, for example, the case of the parlour-door hinge:

"Every day for at least ten years together did my father resolve to have it mended,-----tis not mended yet…" (III.XXI)

To mend the parlour-door hinge, in this typically good-natured Sternean metaphor, would be to resolve matters; and the ultimate resolution of the matter of life, of course, is its termination. An end to be escaped at practically any cost.

3 Method (The Serpentine, or Scriptural Indeterminism)

Volume IX, Chapter IX: "A thousand of my father's most subtle syllogisms could not have said more for celibacy."

4 Temporal Structure of the Work

Volume VI, Chapter XL: "I am now beginning to get fairly into my work."

5 White Pages (Time Passing)

Volume IX, Chapters XVIII/XIX:"---You shall see the very place, Madam; said my uncle Toby."

6 Black Page (The Passing of Yorick)

Volume I, Chapter XII: "Yorick followed Eugenius with his eyes to the door,---he then closed them,---and never opened them more."

7 The Score (Rhythm of the Work)

Volume IX, Chapter XX. Cf. Vol. I, Chapter XX: "My uncle Toby would never offer to answer this by any other kind of argument, than that of whistling half a dozen bars of Lillabullero."

8 "Nor marble monuments..."

Some unique marbled pages from copies of the first edition of The Life and Opinions of Tristram Shandy, Gentleman, Volume III (1762). ("Nor marbled monuments": from Lucan's Pharsalia, trans. Nicholas Rowe, 1812)

(Marbled pages from copies in the National Library of Wales and Firestone Library, Princeton University: these and above images of pages from various editions of Tristram Shandy, via Tristram Shandy Web)