Old town of Eivissa (Ibiza), viewed from the sea: photo by Forbfruit, 14 September 2003

Old town of Eivissa (Ibiza), viewed from the sea: photo by Forbfruit, 14 September 2003

It was in 1932, in the western islands of the Baleares, that I first met Walter Benjamin. It was also the year that he came to Spain for the first time, crossing that fatal border where, as a German desperately trying to flee from other Germans, he was to take his own life eight years later.

Ibiza was not well known to tourists at the time, but a few Americans lived in Santa Eulalia on the east coast, and in San Antonio, on the west coast, a number of Germans were voluntarily practicing an exile that they would later be forced to endure. Between the two, in the small town of Ibiza, I was the only Frenchman on the entire island.

Steep staircase in Eivissa (Ibiza): photo by Hans Bernhard, 16 November 2007

Steep staircase in Eivissa (Ibiza): photo by Hans Bernhard, 16 November 2007

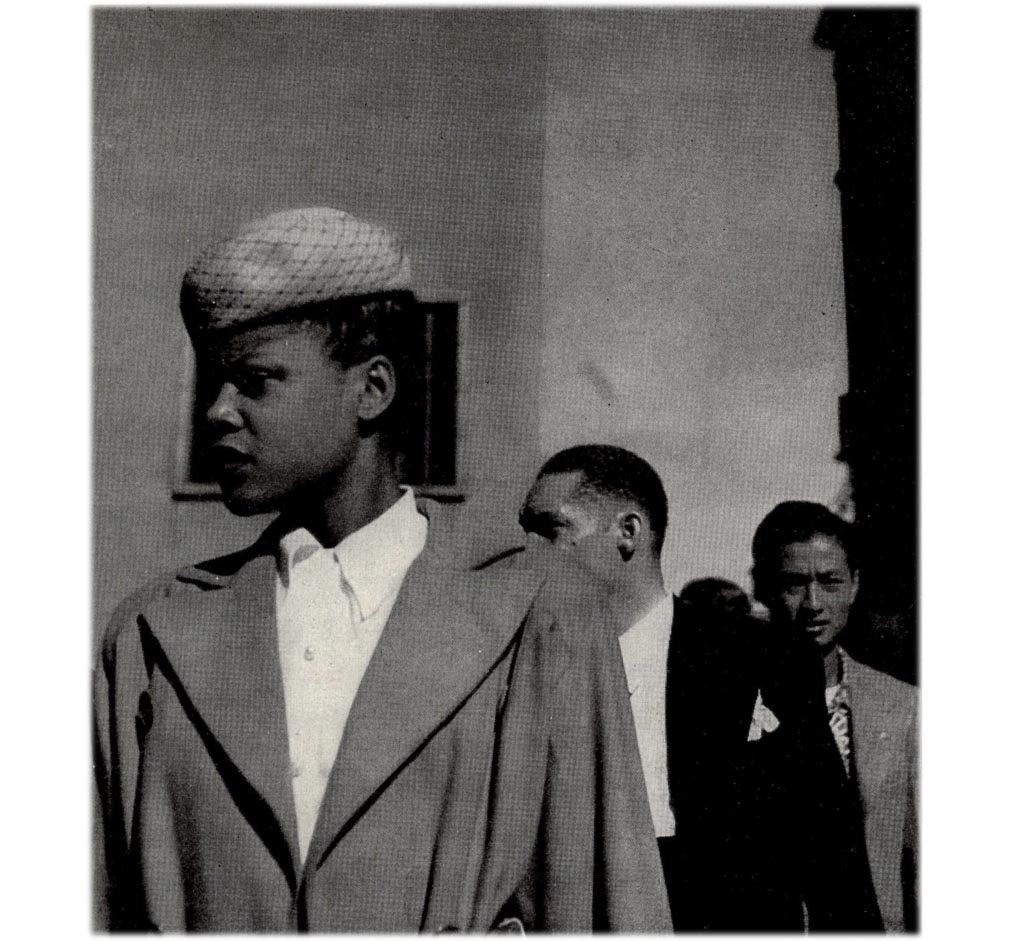

[Benjamin] was awkward and shy, but these qualities were like a shabby suit worn by a rich man who wants to conceal his wealth. For Benjamin, wealth meant a powerful capacity for thought: his thinking was anything but timid and his dialectical skill was remarkable. Armed with both of these, he could easily afford to appear awkward.

Benjamin's physical stoutness and the rather Germanic heaviness he presented were in strong contrast to the agility of his mind, which so often made his eyes sparkle behind his glasses. I can see him in a small photograph I saved, with his prematurely gray, closely cropped hair (he was forty years old at the time), his slightly Jewish profile and black moustache, sitting on a deck chair in front of my house, in his usual posture: face leaned forward, chin held in his right hand. I don't think I have ever seen him think without holding his chin, unless he was carrying in his hand the large curved pipe with the wide bowl he was so fond of and which in a way resembled him.

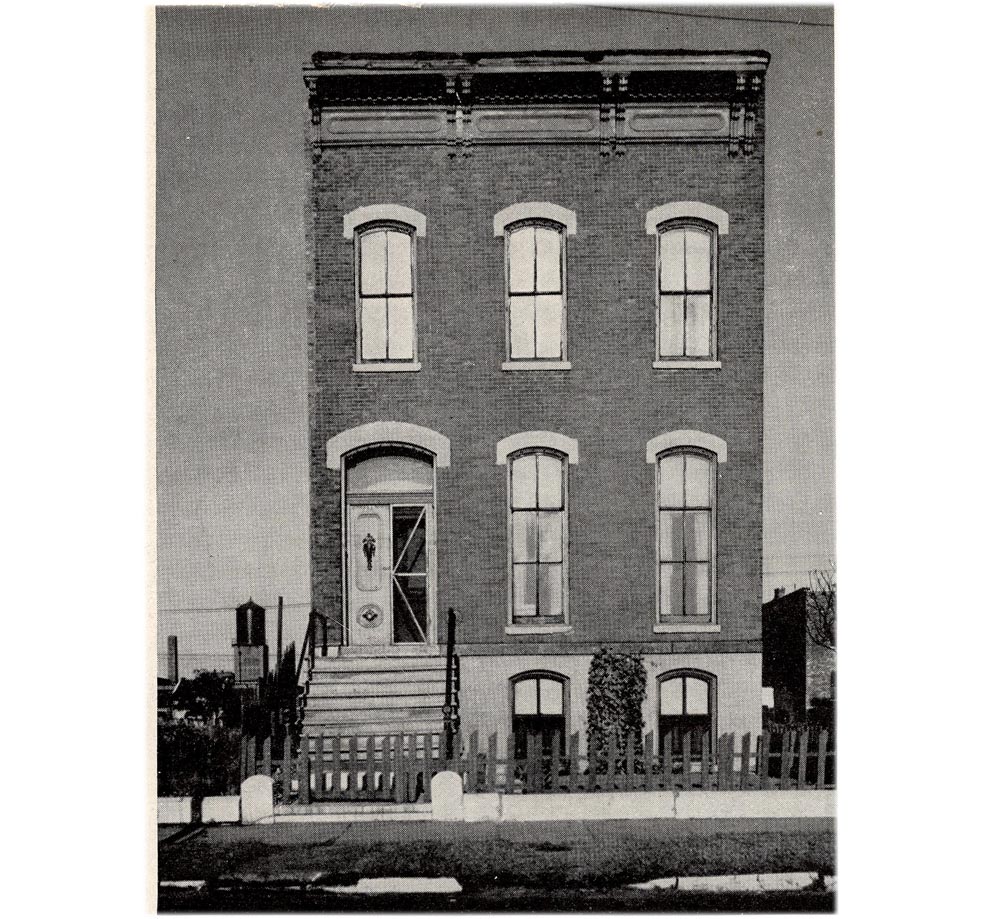

Benjamin lived in a small peasant's house on the San Antonio bay called Frasquito's house, surrounded by fig trees and situated behind a windmill with broken sails. On a radio show in 1952 called "Ibiza, Its Mysteries Myths," I told the story of Frasquito and his mill, which no one was allowed to enter: he had given it to his son and had been waiting thirty-five years for him to return to South America where he had mysteriously disappeared.

Ancient quarry ("Little Atlantis"),San Antonio Bay, Ibiza, Balearic Islands: photo by Thomas G. Clark, 7 June 2011Hans Bernhard, 16 November 2007

Benjamin had difficulty walking: he couldn't go very fast, but was able to walk for long periods of time. The long walks we took together through the rolling countryside, among carob, almond and pine trees, were made even longer by our conversations, which constantly forced him to stop. He admitted that walking kept him from thinking. Whenever something interested him he would say "Tiens, tiens!" This was the signal that he was about to think, and therefore stop. There were times when he said "So, so," as if speaking to himself, but usually it was "Tiens, tiens," even while speaking German with other Germans, the younger and less respectful of whom nicknamed him Tiens-tiens as a result.

One day we were struck by the beauty and aristocratic bearing of the peasant women, whose gait imparted a particular movement to their long, pleated skirts because of the eight or more superimposed petticoats they wore underneath. The large number of these petticoats was a matter of some puzzlement for Benjamin, and he asked a peasant the reason for it. The man replied: "When the women work in the field, they have to bend over. If anyone is watching them, the petticoats are a lot more practical." Benjamin said "Tiens, tiens" and then found the conclusion to the peasant's words. "He is right. It is proper to include modesty under the category of practical matters." Thus, from a small observation based on a tiny detail, his thought always went very far, feeding the conversation with his most personal opinions.

Ibiza, old town: photo by Fijayc, 18 January 2008

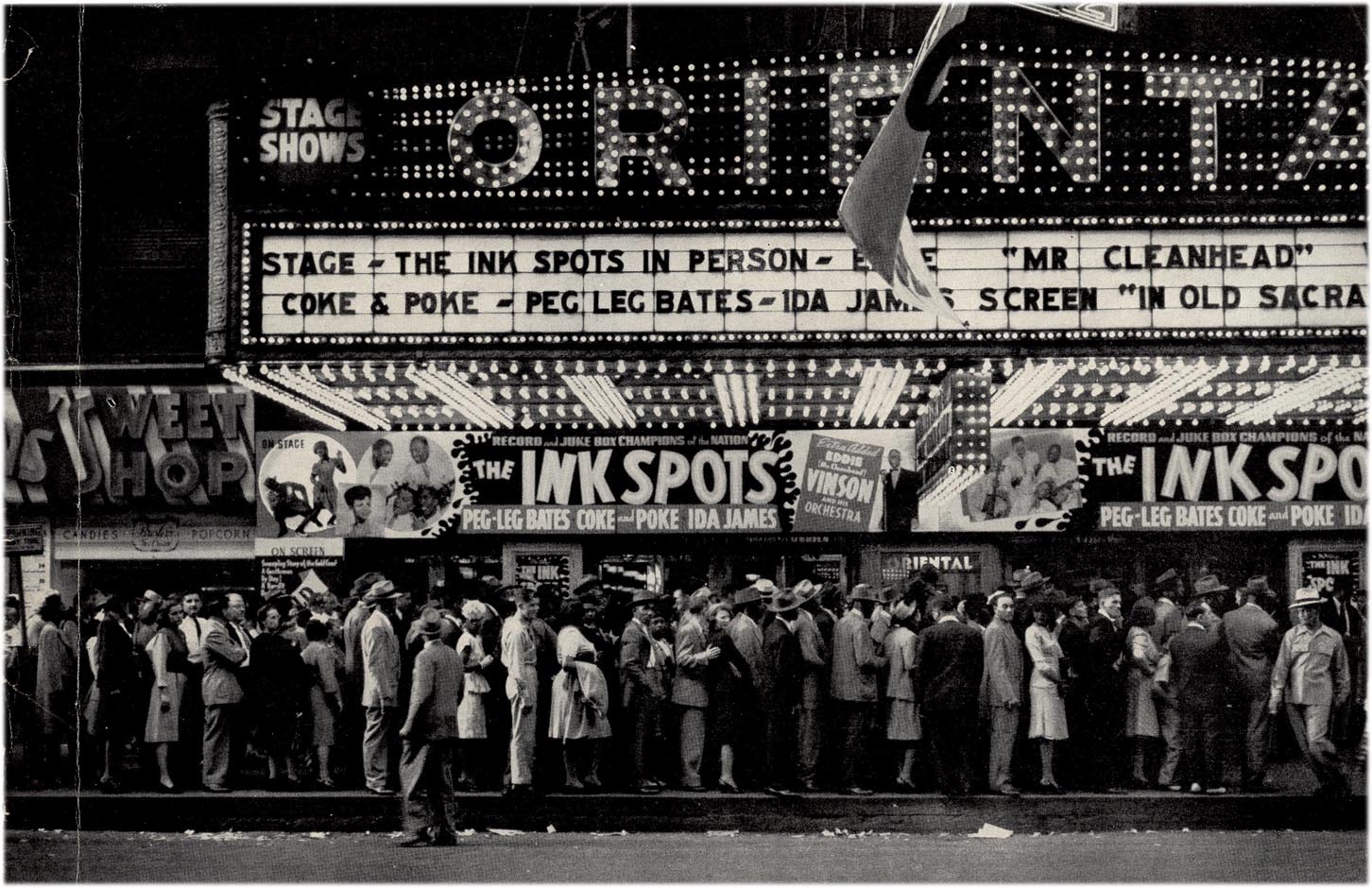

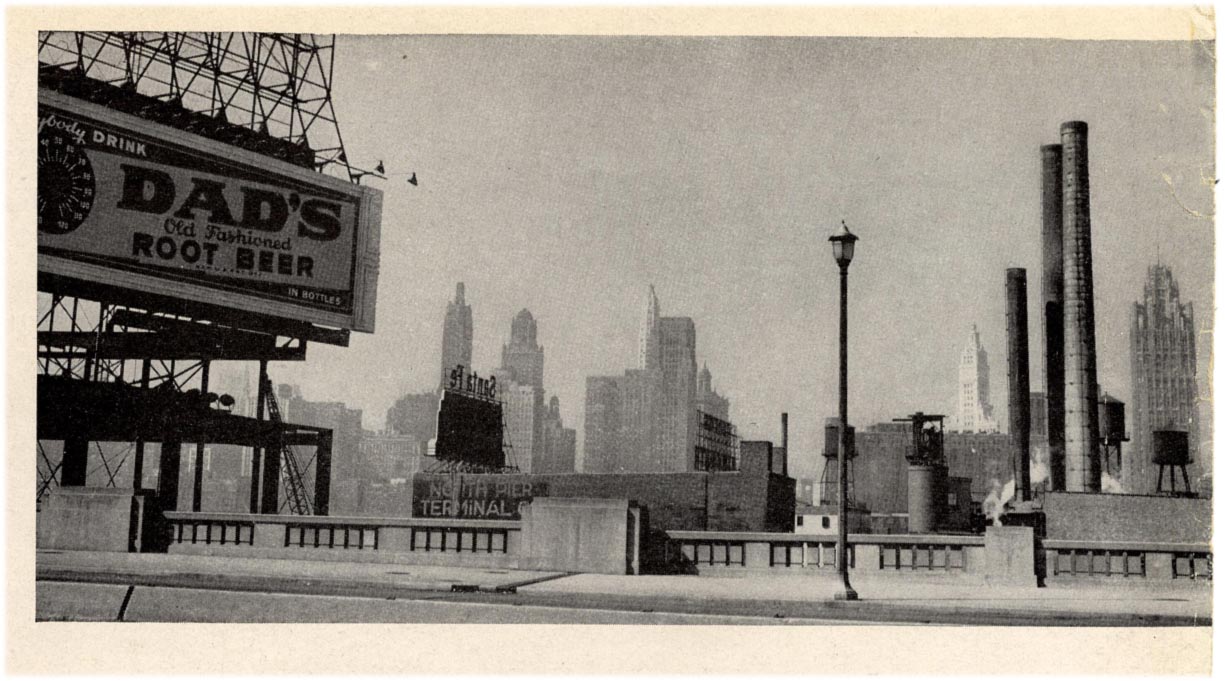

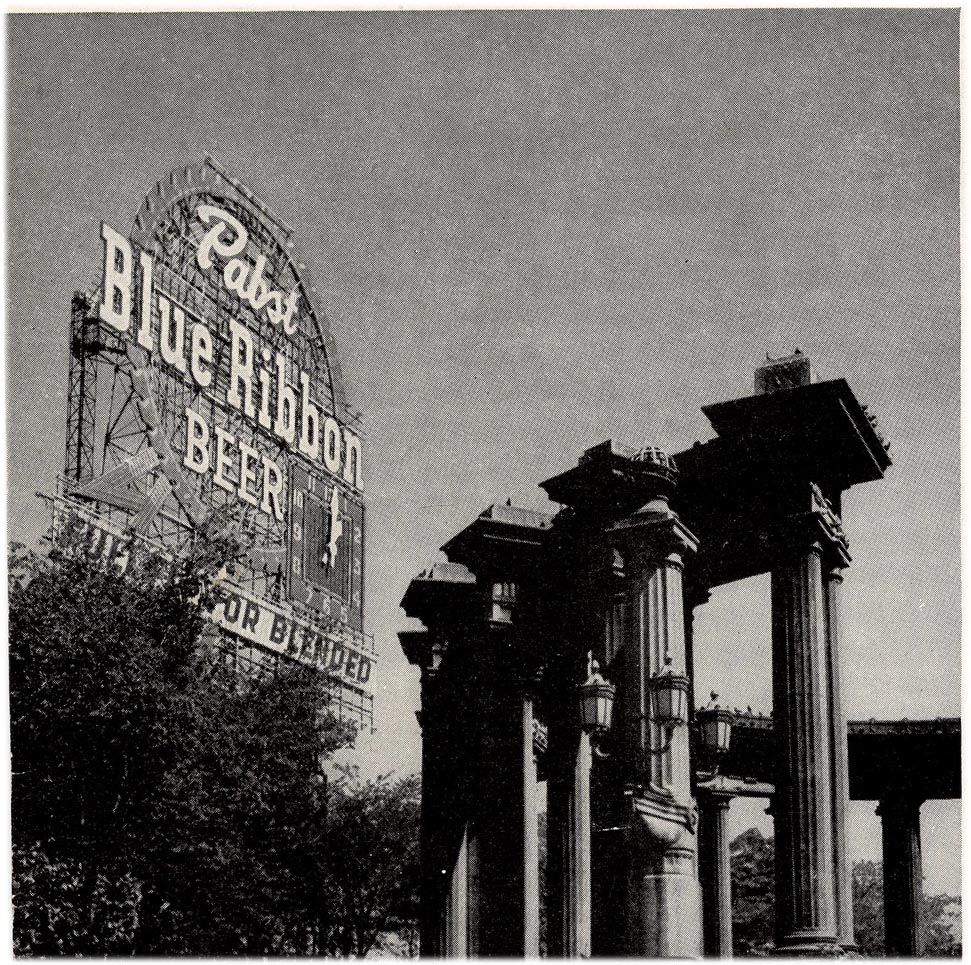

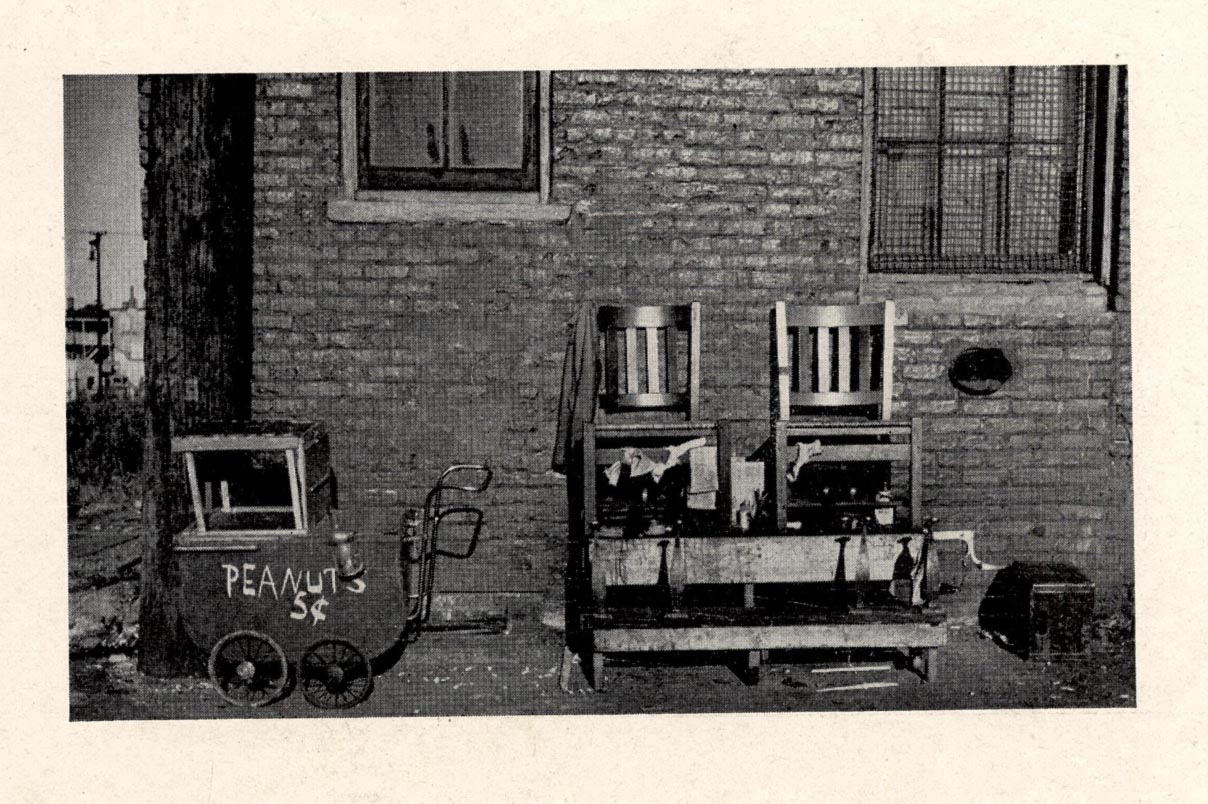

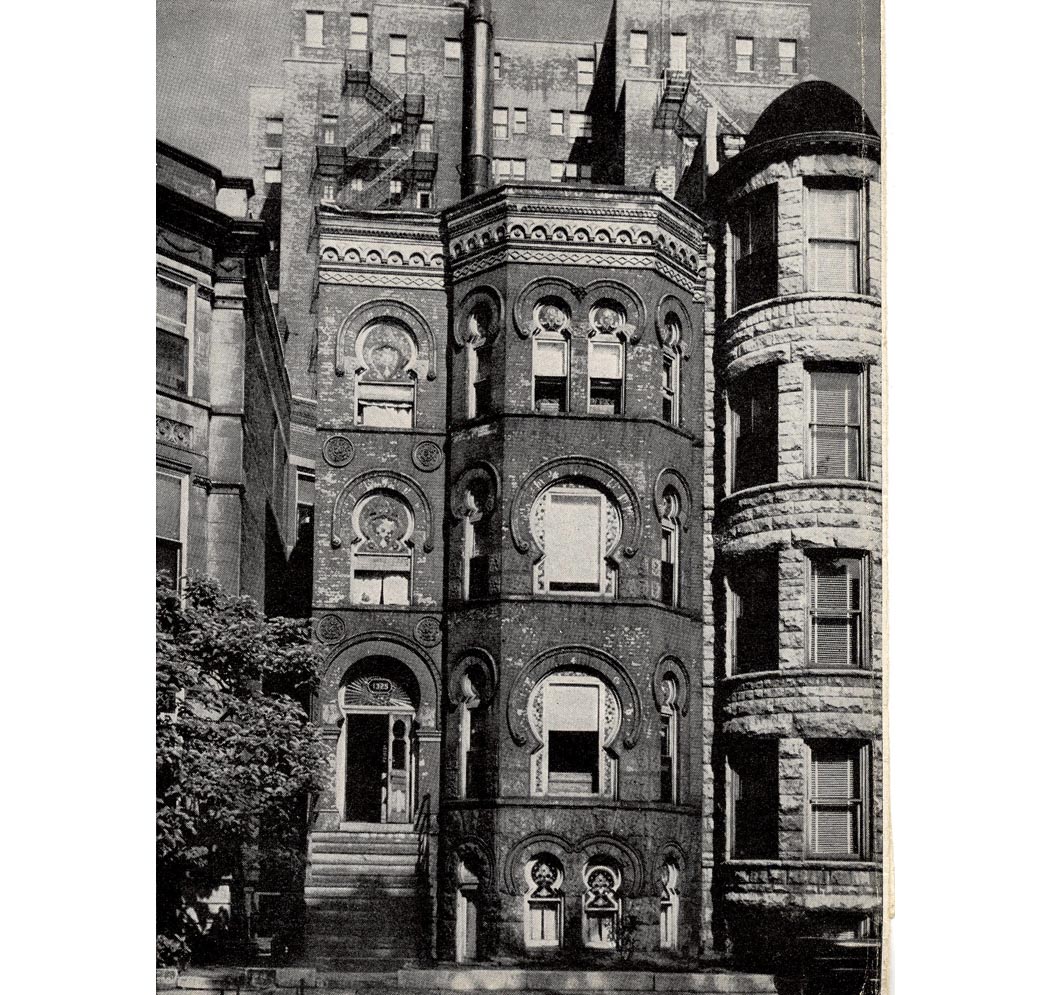

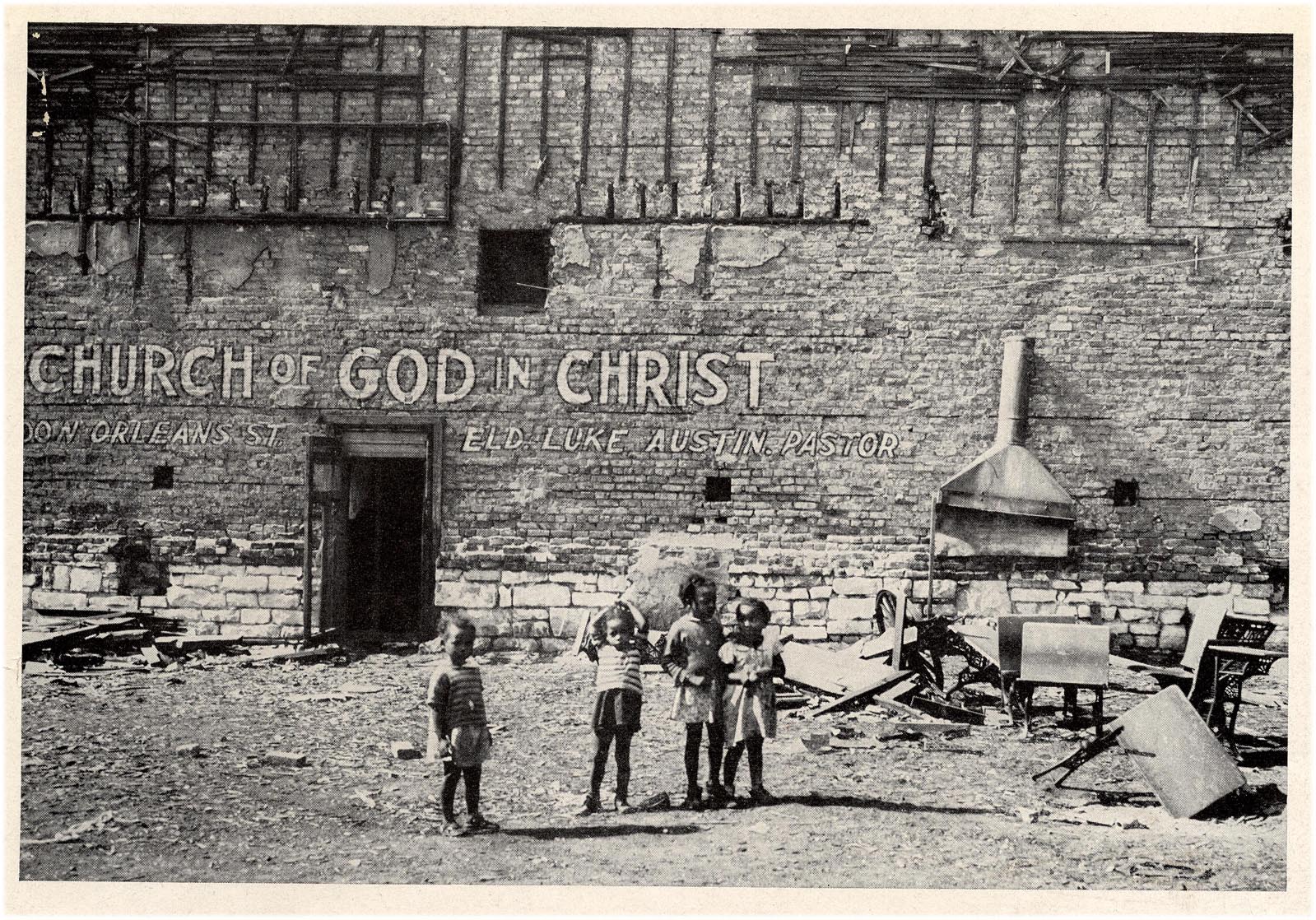

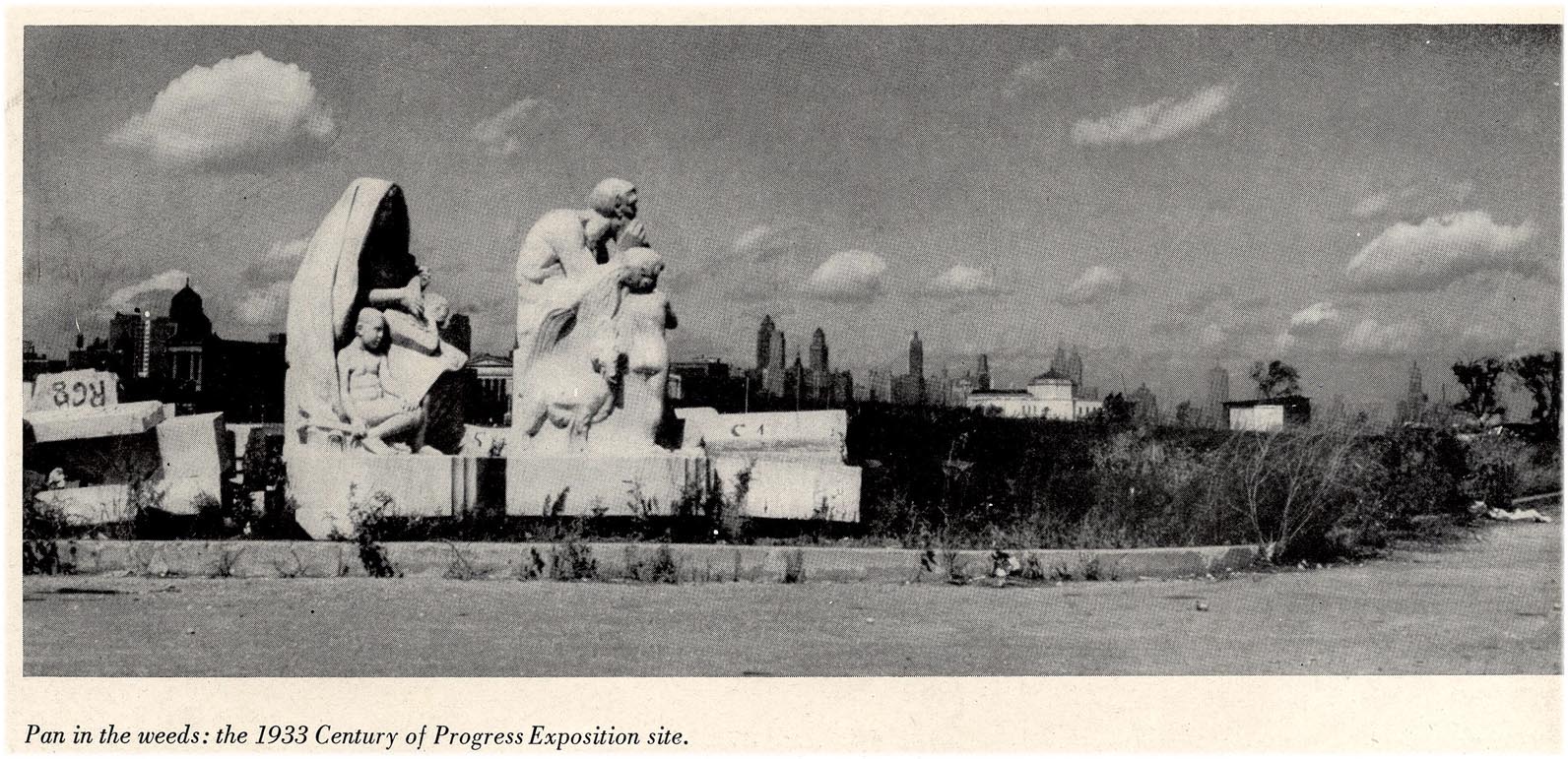

[Spring, 1933]. An elegant new bar had just opened up in the port of Ibiza, and it took its name from a southerly wind: The Migjorn. It soon became the favorite meeting place for foreigners. It was in the Migjorn that an event occurred one evening which was insignificant in itself, but which was to have a strange and decisive effect on my friendship with Benjamin. He usually was a paragon of temperance, but on that night his exceptionally whimsical mood compelled him to ask Toni, the bartender, to mix him a "black cocktail." Without hesitation, Toni went to work and served him a tall glass filled with a black liquid of which I never found out the frightful ingredients. Benjamin drank it down with much aplomb. Soon afterward, a Polish woman whom I will call Maria Z. sat down at our table and asked us if we had ever tried this famous gin that was a specialty of the house. The gin in question was 148 proof: I personally had never been able to swallow a drop. It was a diabolical drink. Maria Z. ordered two glasses for herself and emptied them one right after the other, without batting an eye. She then dared us to do the same. I declined the invitation, but Benjamin took up the challenge, ordered two glasses for himself, and also downed them in quick succession. His face remained impassive, but I soon saw him get up and slowly head for the door. No sooner had he left the bar than he collapsed onto the sidewalk. I ran toward him and managed to get him back on his feet with considerable difficulty. He wanted to walk all the way home to San Antonio. Seeing the unsteadiness of his gait, however, I had to remind him that San Antonio was fifteen kilometers away from Ibiza. I invited him rather to come to my house, where he could sleep in a spare room. He accepted, and we headed in the direction of the upper part of town. I soon realized how foolhardy this was: until that night, the upper part of town had never been so far up. I won't recount how the climb was accomplished, how he required that I walk three meters in front of him, then three meters behind him, how we managed to escalate these streets that were so steep that some of them stopped being streets and turned into stairways, how he sat down at the foot of one of these stairways and fell into deep sleep.... By the time we got to Conquista Street, dawn had started to break -- that green dawn of Ibiza that doesn't seem to come from the sky, but rather from the depths of the old walls themselves, whose whiteness suddenly comes alive with a sickly tinge. Our expedition had lasted the entire night. I must have gotten up around noon, and I went into Benjamin's room to see how he was doing. It was empty! He had disappeared, and I found a little note on the bedside table expressing his gratitude and apology.

Scorcio (Disappearance), Ibiza: photo by simo884,14 May 2011

I didn't see him again for several days. He had returned to San Antonio, and I later learned from one of his friends that he was extremely contrite about what had happened. He didn't dare see me again and wanted to leave Ibiza. Naturally I urged the friend to tell him that such things were of no consequence whatever in my mind, and that it was far from me to hold that night, which after all had been quite out of the ordinary, against him. But when I did see him again, I felt that something inside him had changed. He couldn't forgive himself for having given such a display, for which he felt genuine humiliation and oddly enough, for which he continued to reproach me. Neither the affection nor the respect I held for him were able to convince him that the unfortunate effects of the 148 proof gin hadn't changed my opinion in the least. I first experienced a deep sorrow as a result, and afterwards a certain annoyance. We nonetheless continued our work on the translation of Berliner Kindheit. He no longer came readily to my house, however. One day I invited him to lunch, and he sent me a small note expressing his regrets. "The climb will be most difficult in this heat. I think I would arrive in an exhausted state." So we continued to work in San Antonio, but soon had to stop entirely. Afflicted with a case of brucellosis, I had to spend several hours a day stretched out on a mat without doing anything. Benjamin, for his part, began to suffer from malaria. The idiosyncrasies of his personality were not diminished as a result, and his acerbity became more and more acute, as we were all to experience. And yet, when I think back after all these years and view our little entourage in a more objective light, I can't help discerning the figure of some evil genie working steadily to bring us apart.

Nothing gave our imaginary feud an opportunity to materialize. Yet when Benjamin left Ibiza in October, our friendship had inexplicably cooled. I did receive a friendly letter from him after his departure, but only one. At the end of the year, I returned to Paris.

I was to see him only one more time, at the Café de Flore in March of 1934. He was living at the Palace-Hôtel in Saint-Germain-des-Prés. I wanted to finish the work we had already undertaken, and we exchanged a few letters concerning two new texts from Berliner Kindheit that I was in the process of finishing: "Zwei Blechkapellen" and "Schmetterlingsjagd." We were supposed to meet on April 20. The day before, I received a note canceling our appointment. "It is with great bitterness," he wrote, "that I find I must submit to the malevolent constellation which seems to have been ruling over us for some time. I'm writing these lines before an unexpected departure."

He did not give me the reason for this departure, and I never heard from him again. Our friendship thus vanished behind the veil of mystery with which he enjoyed surrounding certain phenomena of his life and thought, and this disappearance was never to be illuminated by more than the vague glimmer of a "malevolent constellation."

Even his death was shrouded in mystery. To this day I am not certain of its details. Professor Theodor Adorno, his close friend and the executor of his literary estate, wrote me the following:

The day of Walter Benjamin's death could not be determined with absolute certainty; we think it was on September 26, 1940. Benjamin crossed the Pyrenees with a small group of emigrés in order to find refuge in Spain. The group was intercepted in Port-Bou by the Spanish police, which told them they would be sent back the next day to Vichy. In the course of the night, Benjamin ingested a large dose of sleeping pills and resisted with all his strength the care that people attempted to administer to him on the following day.

Jean Selz: from Benjamin in Ibiza ("Walter Benjamin à Ibiza"), trans. by M. Martin Guiney, Les Lettres Nouvelles 2, 11 (January 1954), trans. by M. Martin Guiney in On Walter Benjamin: Critical Essays and Recollections, ed. Gary Smith, 1988

Jean Selz (left), Paul Gauguin (the painter’s grandson), Walter Benjamin, and fisherman Tomás Varó (with hat) sailing in the bay of San Antonio, May 1933: photographer unknown, via Cabinet, summer 2008

The preponderance of spirit radically alienated him from his physical and even his psychological existence. As Schoenberg once said of Webern, whose handwriting was reminiscent of Benjamin's, he had put a taboo on animal warmth; friends hardly dared put a hand on his shoulder, and even his death may have to do with the fact that, during the last night in Port Bou, out of shyness the group with which he fled arranged for him to have a single room, with the result that he was able to take unobserved the morphine he had reserved for the utmost emergency.

Theodor Adorno: from Introduction to Benjamin's Schriften (Einleutung zu Benjamin's Schriften), in Benjamin: Schriften, ed. Theodor W. Adorno and Gretel Adorno, 1955, trans. by R. Hullot-Kentor in On Walter Benjamin: Critical Essays and Recollections, ed. Gary Smith, 1988