.

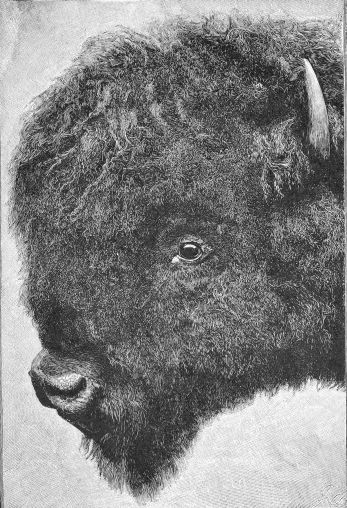

Head of Buffalo Bull: from specimen in the National Museum Group (Cosmopolitan Magazine)

Although the range of the northern herd covered about twice as much territory as did the southern, the latter contained probably twice as many buffaloes. The number of individuals in the southern herd in the year 1871 must have been at least three millions, and most estimates place the total much higher than that.

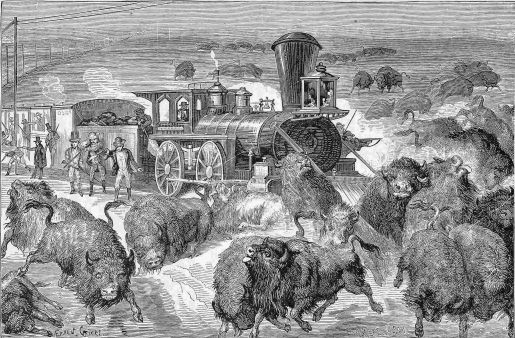

During the years from 1866 to 1871, inclusive, the Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fé Railway and what is now known as the Kansas Pacific, or Kansas division of the Union Pacific Railway, were constructed from the Missouri River westward across Kansas, and through the heart of the southern buffalo range. The southern herd was literally cut to pieces by railways, and every portion of its range rendered easily accessible. There had always been a market for buffalo robes at a fair price, and as soon as the railways crossed the buffalo country the slaughter began. The rush to the range was only surpassed by the rush to the gold mines of California in earlier years. The railroad builders, teamsters, fortune-seekers, “professional” hunters, trappers, guides, and everyone out of a job turned out to hunt buffalo for hides and meat. The merchants who had already settled in all the little towns along the three great railways saw an opportunity to make money out of the buffalo product, and forthwith began to organize and supply hunting parties with arms, ammunition, and provisions, and send them to the range. An immense business of this kind was done by the merchants of Dodge City (Fort Dodge), Wichita, and Leavenworth, and scores of smaller towns did a corresponding amount of business in the same line. During the years 1871 to 1874 but little else was done in that country except buffalo killing. Central depots were established in the best buffalo country, from whence hunting parties operated in all directions. Buildings were erected for the curing of meat, and corrals were built in which to heap up the immense piles of buffalo skins that accumulated. At Dodge City, as late as 1878, Professor Thompson saw a lot of baled buffalo skins in a corral, the solid cubical contents of which he calculated to equal 120 cords.

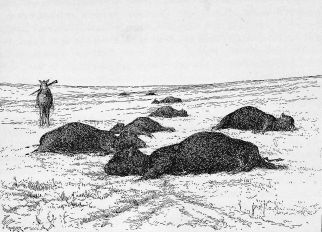

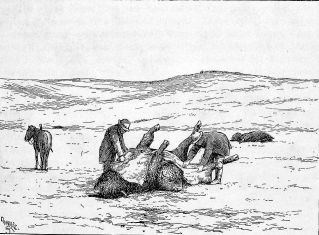

Five Minutes' Work: from a photograph by L. A. Huffman.

At first the utmost wastefulness prevailed. Everyone wanted to kill buffalo, and no one was willing to do the skinning and curing. Thousands upon thousands of buffaloes were killed for their tongues alone, and never skinned. Thousands more were wounded by unskillful marksmen and wandered off to die and become a total loss. But the climax of wastefulness and sloth was not reached until the enterprising buffalo-butcher began to skin his dead buffaloes by horse-power. The process is of interest, as showing the depth of degradation to which a man can fall and still call himself a hunter. The skin of the buffalo was ripped open along the belly and throat, the legs cut around at the knees, and ripped up the rest of the way. The skin of the neck was divided all the way around at the back of the head, and skinned back a few inches to afford a start. A stout iron bar, like a hitching post, was then driven through the skull and about 18 inches into the earth, after which a rope was tied very firmly to the thick skin of the neck, made ready for that purpose. The other end of this rope was then hitched to the whiffletree of a pair of horses, or to the rear axle of a wagon, the horses were whipped up, and the skin was forthwith either torn in two or torn off the buffalo with about 50 pounds of flesh adhering to it. It soon became apparent to even the most enterprising buffalo skinner that this method was not an unqualified success, and it was presently abandoned.

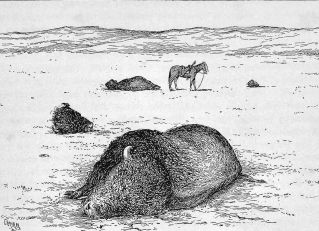

A Dead Bull: from a photograph by L. A. Huffman

The slaughter which began in 1871 was prosecuted with great vigor and enterprise in 1872, and reached its height in 1873. By that time, the buffalo country fairly swarmed with hunters, each party putting forth its utmost efforts to destroy more buffaloes than its rivals. By that time experience had taught the value of thorough organization, and the butchering was done in a more business-like way. By a coincidence that proved fatal to the bison, it was just at the beginning of the slaughter that breech-loading, long-range rifles attained what was practically perfection. The Sharps 40-90 or 45-120, and the Remington were the favorite weapons of the buffalo-hunter, the former being the one in most general use. Before the leaden hail of thousands of these deadly breech-loaders the buffaloes went down at the rate of several thousand daily during the hunting season.

During the years 1871 and 1872 the most wanton wastefulness prevailed. Colonel Dodge declares that, though hundreds of thousands of skins were sent to market, they scarcely indicated the extent of the slaughter. Through want of skill in shooting and want of knowledge in preserving the hides of those slain by green hunters, one hide sent to market represented three, four, or even five dead buffalo. The skinners and curers knew so little of the proper mode of curing hides, that at least half of those actually taken were lost. In the summer and fall of 1872 one hide sent to market represented at least three dead buffalo. This condition of affairs rapidly improved; but such was the furor for slaughter, and the ignorance of all concerned, that every hide sent to market in 1871 represented no less than five dead buffalo.

Scene on the Buffalo Range: from a photograph by L. A. Huffman

By 1873 the condition of affairs had somewhat improved, through better organization of the hunting parties and knowledge gained by experience in curing. For all that, however, buffaloes were still so exceedingly plentiful, and shooting was so much easier than skinning, the latter was looked upon as a necessary evil and still slighted to such an extent that every hide actually sold and delivered represented two dead buffaloes.

In 1874 the slaughterers began to take alarm at the increasing scarcity of buffalo, and the skinners, having a much smaller number of dead animals to take care of than ever before, were able to devote more time to each subject and do their work properly. As a result, Colonel Dodge estimated that during 1874, and from that time on, one hundred skins delivered represented not more than one hundred and twenty-five dead buffaloes; but that “no parties have ever got the proportion lower than this.”

Buffalo Skinners at Work: from a photograph by L. A. Huffman

The great southern herd was slaughtered by still-hunting. A typical hunting party is thus described by Colonel Dodge:

"The most approved party consisted of four men -- one shooter, two skinners, and one man to cook, stretch hides, and take care of camp. Where buffalo were very plentiful the number of skinners was increased. A light wagon, drawn by two horses or mules, takes the outfit into the wilderness, and brings into camp the skins taken each day. The outfit is most meager: a sack of flour, a side of bacon, 5 pounds of coffee, tea, and sugar, a little salt, and possibly a few beans, is a month’s supply. A common or 'A' tent furnishes shelter; a couple of blankets for each man is a bed. One or more of Sharps or Remington’s heaviest sporting rifles, and an unlimited supply of ammunition, is the armament; while a coffee-pot, Dutch-oven, frying-pan, four tin plates, and four tin cups constitute the kitchen and table furniture.

“The skinning knives do duty at the platter, and ‘fingers were made before forks.’ Nor must be forgotten one or more 10-gallon kegs for water, as the camp may of necessity be far away from a stream. The supplies are generally furnished by the merchant for whom the party is working, who, in addition, pays each of the party a specified percentage of the value of the skins delivered. The shooter is carefully selected for his skill and knowledge of the habits of the buffalo. He is captain and leader of the party. When all is ready, he plunges into the wilderness, going to the center of the best buffalo region known to him, not already occupied (for there are unwritten regulations recognized as laws, giving to each hunter certain rights of discovery and occupancy). Arrived at the position, he makes his camp in some hidden ravine or thicket, and makes all ready for work.”

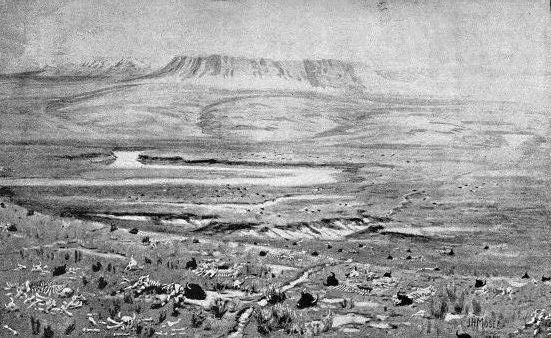

Of course the slaughter was greatest along the lines of the three great railways -- the Kansas Pacific, the Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fé, and the Union Pacific, about in the order named. It reached its height in the season of 1873. During that year the Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fé Railroad carried out of the buffalo country 251,443 robes, 1,017,600 pounds of meat, and 2,743,100 pounds of bones. The end of the southern herd was then near at hand. Could the southern buffalo range have been roofed over at that time it would have made one vast charnel-house. Putrifying carcasses, many of them with the hide still on, lay thickly scattered over thousands of square miles of the level prairie, poisoning the air and water and offending the sight. The remaining herds had become mere scattered bands, harried and driven hither and thither by the hunters, who now swarmed almost as thickly as the buffaloes. A cordon of camps was established along the Arkansas River, the South Platte, the Republican, and the few other streams that contained water, and when the thirsty animals came to drink they were attacked and driven away, and with the most fiendish persistency kept from slaking their thirst, so that they would again be compelled to seek the river and come within range of the deadly breech-loaders. Colonel Dodge declares that in places favorable to such warfare, as the south bank of the Platte, a herd of buffalo has, by shooting at it by day and by lighting fires and firing guns at night, been kept from water until it has been entirely destroyed. In the autumn of 1873, when Mr. William Blackmore traveled for some 30 or 40 miles along the north bank of the Arkansas River to the east of Fort Dodge, “there was a continuous line of putrescent carcasses, so that the air was rendered pestilential and offensive to the last degree. The hunters had formed a line of camps along the banks of the river, and had shot down the buffalo, night and morning, as they came to drink. In order to give an idea of the number of these carcasses, it is only necessary to mention that I counted sixty-seven on one spot not covering 4 acres.”

White hunters were not allowed to hunt in the Indian Territory, but the southern boundary of the State of Kansas was picketed by them, and a herd no sooner crossed the line going north than it was destroyed. Every water-hole was guarded by a camp of hunters, and whenever a thirsty herd approached, it was promptly met by rifle-bullets.

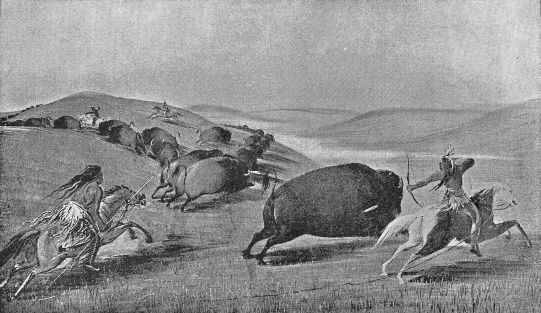

During this entire period the slaughter of buffaloes was universal. The man who desired buffalo meat for food almost invariably killed five times as many animals as he could utilize, and after cutting from each victim its very choicest part -- the tongue alone, possibly, or perhaps the hump and hind quarters, one or the other, or both -- fully four-fifths of the really edible portion of the carcass would be left to the wolves. It was no uncommon thing for a man to bring in two barrels of salted buffalo tongues, without another pound of meat or a solitary robe. The tongues were purchased at 25 cents each and sold in the markets farther east at 50 cents. In those days of criminal wastefulness it was a very common thing for buffaloes to be slaughtered for their tongues alone. Mr. George Catlin relates that a few days previous to his arrival at the mouth of the Tetón River (Dakota), in 1832, “an immense herd of buffaloes had showed themselves on the opposite side of the river,” whereupon a party of five or six hundred Sioux Indians on horseback forded the river, attacked the herd, recrossed the river about sunset, and came into the fort with fourteen hundred fresh buffalo tongues, which were thrown down in a mass, and for which they required only a few gallons of whisky, which was soon consumed in “a little harmless carouse.” Mr. Catlin states that from all that he could learn not a skin or a pound of meat, other than the tongues, was saved after this awful slaughter.

The Chase on Horseback: from a painting by George Catlin (National Museum)

Judging from all accounts, it is making a safe estimate to say that probably no fewer than fifty thousand buffaloes have been killed for their tongues alone, and that most of these are undoubtedly chargeable against white men, who ought to have known better.

A great deal has been said about the slaughter of buffaloes by foreign sportsmen, particularly Englishmen; but I must say that, from all that can be ascertained on this point, this element of destruction has been greatly exaggerated and overestimated. It is true that every English sportsman who visited this country in the days of the buffalo always resolved to have, and did have, “a buffalo hunt,” and usually under the auspices of United States Army officers. Undoubtedly these parties did kill hundreds of buffaloes, but it is very doubtful whether the aggregate of the number slain by foreign sportsmen would run up higher than ten thousand. Indeed, for myself, I am well convinced that there are many old ex-still-hunters yet living, each of whom is accountable for a greater number of victims than all buffaloes killed by foreign sportsmen would make added together. The professional butchers were very much given to crying out against “them English lords,” and holding up their hands in holy horror at buffaloes killed by them for their heads, instead of for hides to sell at a dollar apiece; but it is due the American public to say that all this outcry was received at its true value and deceived very few. By those in possession of the facts it was recognized as “a blind,” to divert public opinion from the real culprits.

Nevertheless it is very true that many men who were properly classed as sportsmen, in contradistinction from the pot-hunters, did engage in useless and inexcusable slaughter to an extent that was highly reprehensible, to say the least. A sportsman is not supposed to kill game wantonly, when it can be of no possible use to himself or any one else, but a great many do it for all that. Indeed, the sportsman who kills sparingly and conscientiously is rather the exception than the rule. Colonel Dodge thus refers to the work of some foreign sportsmen:

"In the fall of that year [1872] three English gentlemen went out with me for a short hunt, and in their excitement bagged more buffalo than would have supplied a brigade.” As a general thing, however, the professional sportsmen who went out to have a buffalo hunt for the excitement of the chase and the trophies it yielded, nearly always found the bison so easy a victim, and one whose capture brought so little glory to the hunter, that the chase was voted very disappointing, and soon abandoned in favor of nobler game. In those days there was no more to boast of in killing a buffalo than in the assassination of a Texas steer.

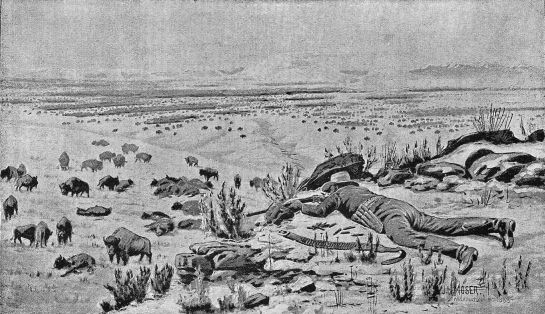

Where the Millions Have Gone: from a painting by J. H. Moser (National Museum)

It was, then, the hide-hunters, white and red, but especially white, who wiped out the great southern herd in four short years. The prices received for hides varied considerably, according to circumstances, but for the green or undressed article it usually ranged from 50 cents for the skins of calves to $1.25 for those of adult animals in good condition. Such prices seem ridiculously small, but when it is remembered that, when buffaloes were plentiful it was no uncommon thing for a hunter to kill from forty to sixty head in a day, it will readily be seen that the chances of making very handsome profits were sufficient to tempt hunters to make extraordinary exertions. Moreover, even when the buffaloes were nearly gone, the country was overrun with men who had absolutely nothing else to look to as a means of livelihood, and so, no matter whether the profits were great or small, so long as enough buffaloes remained to make it possible to get a living by their pursuit, they were hunted down with the most determined persistency and pertinacity.

15 comments:

What a legacy those "hunter/ butchers" left us--devastatingly disgustful.

see if y'all can find this film:

http://rapidcityjournal.com/news/local/top-stories/article_dc7fc704-fe76-51f0-a09e-ae934ddd7439.html

(hope I clicked the right "copy" button):

title is "Good Meat: How tThe Lakota Got Fat and Beau LeBeau Saved Himself"

Vassilis, no sane person could respond otherwise to this. Although one might equally say no sane person would shoot elk from a helicopter, or be numbered among the stunted legions of the tea party.

Mr Hornaday was a professional zoologist who devoted a good bit of time and attention to field studies of the last Bison in their vanishing habitat, and a good deal of additional time and attention attempting to preserve "specimens" of what remained of the species. His long, eloquent, outraged monograph is terrible and wonderful in detail, terrible for what it tells, wonderful in that it reveals much truth. Of course no one wanted to hear such truths then, much as now.

It may well be that the last hope for this continent ended at the moment the first white man set foot upon it.

Ed,

The lore is rich and abundant though the contact with the present is a bit hard to make out. One strains one's ears and eyes.

The Buffalo Hunter

hey

that's "right on" :

"the present is a bit hard to make out"

actually, these daze, everything is a bit hard to "get a handle on"

I am just now getting into what is now being called "contextual" as in poetry, art, etc

have as yet not gotten much beyond the standard

dictionary definition of "context"

I just went for a 2-mile walk first time I've left my "cave" in 37 years !

same trail through this section of The Longbranch ...

took my cane just in case I had to beat of a charging, pissed off White Buffalo...

now?

water, a nap, then.... into my own mind's lore's twists-&-turns, as :::

ARS POETIC HER

It's almost impossible to project oneself into the mentality of these craven butchers. (But that term is an insult to real butchers.) Is there a switch in the human brain, do you think? One that activates the lust old John Chivington articulated before the Sand Creek Massacre, that he "long[ed] to wade in gore"? DNA researchers would do well to shift their focus from curing baldness to finding that switching and disabling it....

Ed, That hike sounds fine. Next time you can carry me on your back. Like a buffalo skin at Boystown.

Joseph, this history is hard to stomach -- presuming hopefully it's just history, yet fearing, from what we see around us, otherwise. The rising gorge, the rising sense of distaste, the awful realization that that DNA pool is a quicksand wallow we'll never escape from as a species, even as we bring other species down with us ... Amen to your utopian proposal that some of the lab geeks figure out how to turn off the gore switch. But homo necans, man the killer, may have locked the switch into an "on" position, at some point along the (d)evolutionary line.

I remember living up in your neck of the woods and being scared to death by the great white (yet red of neck) hunters with web hats and rifle racks mounted on their four by fours. They'd drive up into the mountains after Broncos games and if there were no animals to shoot, then just blast away at old refrigerators, junked cars, etc.

Just to prove who's boss I guess. You'd have almost thought there was a war on. It made one fear to walk among those woods.

first cousin of the buffalo ... the cow/cattle.

here is how it is done just about everywhere in the U.S.A. (thanks to Henry Ford's assembly-line and American Ingenuity !: :

http://www.humanesociety.org/news/news/2008/01/undercover_investigation_013008.html

most people think meat grows in little, sterile styrephone and is wrapped in see-through shrink-wrapped cellophane !

and we wonder why we are in the age of run-away cancer ...

Thankfully, there was a man - Scotty Philip - in South Dakota who made it his mission to save the buffalo after this terrible slaughtering. Many of the bison from his herd went to National and state parks after his death.

here around here in Virginia not sure what is in Maryland a list of Buffalo Farms ...

Buffalo Meat Processing Ranches not 1852 but 2011:

http://www.eatbisonmeat.com/webapp/GetPage?pid=56

I saw some buffalo hamburger up at the local "Gourmet" food store ... $12.49 per pound !

heck

can Armour and Swift's be far behind ?

and imported PHONY buffalo meat from Asia

just like our Atlantic Salmon now comes from a fish farm (a swimming pool) in Viet Nam !

and the fu*&*$ng crap is colored with a dye to make the white salmon look PINK !

and the destruction goes on unfortunatelly, it must be idiosincratic to the homo sapiens. just think about what NOW is happening to rain forests!

Ed, Antonio, Marcia, we dwell together in sorrow before all this.

Marcia reminds me of the critical efforts on the part of men like Scotty Phillip to save the Bison.

Ed reminds me that many of the animals in the present herds of the High Plains are being "protected"... to become buffalo meat.

Looking into the history in this area quickly becomes a looking-into the history of the White and Red man in America, each with distinct ways and uses.

I turned up several stories of the still-hunting professionals, experts who were responsible for a large share of the slaughter.

The following is the story of one of these "heroes" of the frontier.

The .50-90 Sharps black powder rifle cartridge was introduced to the weapons market in 1872 by Sharps Rifle Manufacturing Company, with ballistics designed for big-game hunting. Specifically, the .50-90 cartridge was a buffalo hunting round; powerful enough to take down the continent's largest land animal in a single shot. The cartridge incorporated a heavy bullet and a large black powder load, producing extremely high muzzle energies. The bullet typically measured 13 mm. in diameter, weighed up to 36 g., and was fired at muzzle energy up to c. 2000 foot-pounds force. The impact of the blast from a "Big .50" was strong enough to topple an American Bison bull at full gallop.

On 27 June 1874, at the Second Battle of Adobe Walls, a famous marksman named William "Billy" Dixon fired a legendary 1538-yard shot with a Sharps .50-90.

Like many of the most accomplished professional buffalo killers of his day Dixon was a "Meti", or half-breed, of mixed European and Native American descent, a hired scout and professional "market hunter" for the railroads. A formidable person with the imposing bearing of one accustomed to a routine of brutal, often casual slaughter.

When buffalo hunters followed the last of the great southern herds into the Texas Panhandle in 1874, Dixon, who had scouted Texas as far south as the Salt Fork of the Red River, became the leader and guide of an organized killing party. He conducted a group of twenty-eight men (and one woman) out onto the Texas Plains, where they set up an outpost called Adobe Walls. Dixon knew the country and so knew that roaming buffalo herds -- and therefore migratory groups of buffalo-hunting Southern Plains Indians -- were abundant.

Seven years earlier the Treaty of Medicine Lodge had laid plans for two reservations in Southern Plains country, one for the Kiowa and Comanche, the other for the Arapaho and Southern Cheyenne. The treaty had nominally encouraged the tribes to engage in commercial market hunting, providing, along with basic necessities, a supply of rifles and ammunition, and license to continue to "hunt on any lands south of the Arkansas River so long as the buffalo may range thereon."

But the food and housing provisions of the treaty proved hollow. Conditions on the reservations were miserable at best. They were in fact little more than prison camps.

Professional buffalo killers like "Billy" Dixon construed the treaty in their own fashion, meanwhile: as license to penetrate Indian lands without governmental hindrance. They hunted the buffalo plains to exhaustion, with little more regard for the native human inhabitants of those plains, who had been dependent on the buffalo for their livelihood, than for the helpless prey.

Indeed the actions of Dixon and his party were part of a larger strategic campaign in the summer of 1874 aimed at usurping the historic territories of the indigenous peoples of the Southern Plains -- the Kiowa, Comanche, Southern Cheyenne and Arapaho tribes. The U.S. Army was charged with the task of causing these peoples by force to do what they were understandably disinclined to do voluntarily, that is, to move out of the westward path of Empire, away from their former hunting grounds and onto reservations. The campaign would constitute a decisive victory for Manifest Destiny and an irrevocable loss of homelands for the native peoples, whose traditional nomadic way, following the roaming Bison herds which had sustained them, would be ended forever.

[continuing...]

The situation of the Indians in that summer was desperate. Medicine and prophecy as well as the pressing realities of imminent starvation combined to dictate a policy of defensive aggression against the white invaders. A charismatic leader, Isa-tai of the Quahadi Comanches, counselled war. He was joined by the widely respected Comanche chief Quanah Parker in mounting a surprise attack against the outpost of the white hunters.

On 27 June 1874 a large band of Comanches, reckoned to number between 700 and 1200, descended upon Adobe Walls. For three days the outpost came under siege. Finally "Billy" Dixon concluded the siege with a flourish. An Indian party was spotted about a mile east of the outpost. Dixon's own rifle, a .45/90, lacking the necessary range, he took aim instead with a hastily-borrowed Sharps "Big .50" buffalo-killing gun, and fired three times. The third attempt, to be storied as The "Shot of the Century", knocked an Indian off his horse almost a mile away. Chief Quanah Parker, at the head of the raiding party, narrowly avoided being hit. The Indian party then fell back.

The setback at Adobe Walls resulted in a general dispersal of the reluctant tribes across the Southern Plains. Isolated raids continued, bringing down the full weight of the U. S. Cavalry upon the renegades.

Three months later the celebrated sharpshooter and bounty hunter "Billy" Dixon was freelancing as an army scout when he, a fellow scout and four cavalrymen were attacked by a mixed group of Kiowas and Comanches at a contested hunting site, a buffalo wallow in Hemphill County. Dixon's deadly rifle fire, together with cold night rains, helped turn back the attack; under Indian fire Dixon set up a defensive position, venturing out at one point to drag a wounded man, his fellow scout, back into the buffalo wallow and safety; for his role in the affair the hired marksman, though a civilian, was awarded the Medal of Honor for Gallantry in Battle.

This engagement was one of a series of pitched battles that bloody summer between whites and Indians across the Texas Panhandle, to become known as the Red River Wars.

An account of his part in the wars is contained in "Billy" Dixon's autobiography, dictated on his deathbed in 1913 to his wife, Olive King Dixon. Dixon had married in 1894 after settling down near Adobe Walls, where he became the first sheriff of Hutchinson County; for the first three years of their marriage Olive would remain the sole female resident of the county. The ex-sharpshooter also became a state land commissioner and justice of the peace. The local Masonic Lodge and a creek in the southern part of the County were given his name.

By that time the Texas Panhandle belonged to the whites, and both those once free-roving beings, the free American Bison and the free American Indian, were long gone from the open ranges.

The famous buffalo hunter and the big gun he used to blow an Indian off a horse at nearly a mile's distance became part of the lore of the frontier, a legend today perpetuated an ocean and more than a century away by the Lancashire Historical Breechloading Smallarms Association. The Association holds an annual Vintage Rifle Open Long Range Championship. Contesting shooters meet up to blaze away at a thousand yards with black powder cartridge rifles modeled after "Billy" Dixon's "Big 50". White people will never forget a powerful weapon. After all, what else have they got.

Today the Indians have their casinos and their cultural memories. Their myths and stories remember a vanished way of life. The American Bison, retrieved from the brink of extinction -- the genetically compromised survivors selectively reintroduced to patches of the old grazing grounds, a few individual animals and small herds protected in conservation preserves, the majority destined for "regulated" commercial slaughter (including "kosher slaughter") -- are perhaps fortunate to remember nothing.

...On a more hopeful note, here are some survivors.

and

wild horse's slaughtered by Alpo to make dog food !

Post a Comment