Panorama. Gowainghat, Sylhet.: photo by Asif Shihat, 28 November 2017

Panorama. Gowainghat, Sylhet.: photo by Asif Shihat, 28 November 2017

Panorama. Gowainghat, Sylhet.: photo by Asif Shihat, 28 November 2017

Smoke on the ... tribune: photo by Piotr Dziurman, 26 November 2017

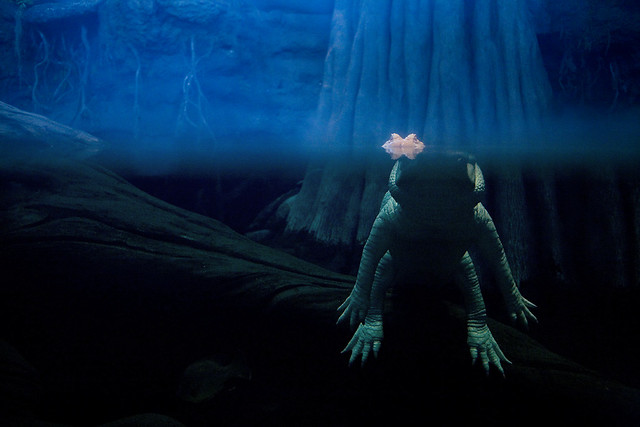

Untitled [albino alligator, California Academy of Sciences]: photo by Naveen Jamal, 10 November 2009

Untitled [Dhaka]: photo by Muhammad Imam Hasan, 26 March 2017

Untitled [Dhaka]: photo by Muhammad Imam Hasan, 25 June 2017

Kolkata: photo by Muhammad Imam Hasan, 26 June 2017

Untitled [Dhaka]: photo by Muhammad Imam Hasan, 27 June 2017

Untitled [Varanasi]: photo by Muhammad Imam Hasan, 27 June 2017

Untitled [Dhaka]: photo by Muhammad Imam Hasan, 2 June 2017

Untitled [Dhaka]: photo by Muhammad Imam Hasan, 7 October 2017

See the beauty of everyday things. Chittagong, Bangladesh.: photo by Ferdousi Begum, 18 November 2017

DSC03217 [NYC]: photo by Kanrapee Chokpaiboon, 1 November 2016

Untitled. AfterParty.: photo by Gabi Ben avraham, 13 March 2017

Shimbashi, Tokyo, Sep 2014. Happy Halloween everyone, but don't drink too much.: photo by Shin Noguchi, sometime in 2014

Sleaze majesté: Aung San Suu Kyi applauds as she sits next to Pope Francis.: photo by Max Rossi/Reuters, 27 November 2017

YANGON,

27 November: Titular Bhud-Queen Onsong Soochy (aka Her Conniving Highness The

Very Nice Little Flower Lady) smirked condescendingly for the cameras

today as she demonstrated to a captive assembly of loyal thug-pod bodhisattonmypuppy devotees and royal guest Pope Francis the size and shape of the iron "shrinking mindfulness claptrap veneration box" into which, were he to be so unwise as to utter the word "Rohingya" at any time during his visit to her kingdom, even by accident while sneezing, his wee papal head would be placed for the traditional Happy/Sad Decapitation By Shrinking Ritual.

Breaking: Little Faux Royal Flower Lady Discharged from Iconic Emblem Status at Oxon, Is Spit Out Of Many Disgusted Mouths

Today

is 25 November, exactly 3 months since violence broke out in #Myanmar.

Since then: 623,000 people fled to #Bangladesh and at least 275 villages

fully/partially burned down in #Rakhine State. The extreme level of

human suffering is much harder to quantify. #RohingyaCrisis: image via Pierre in Myanmar @pierre peron, 25 November 2017

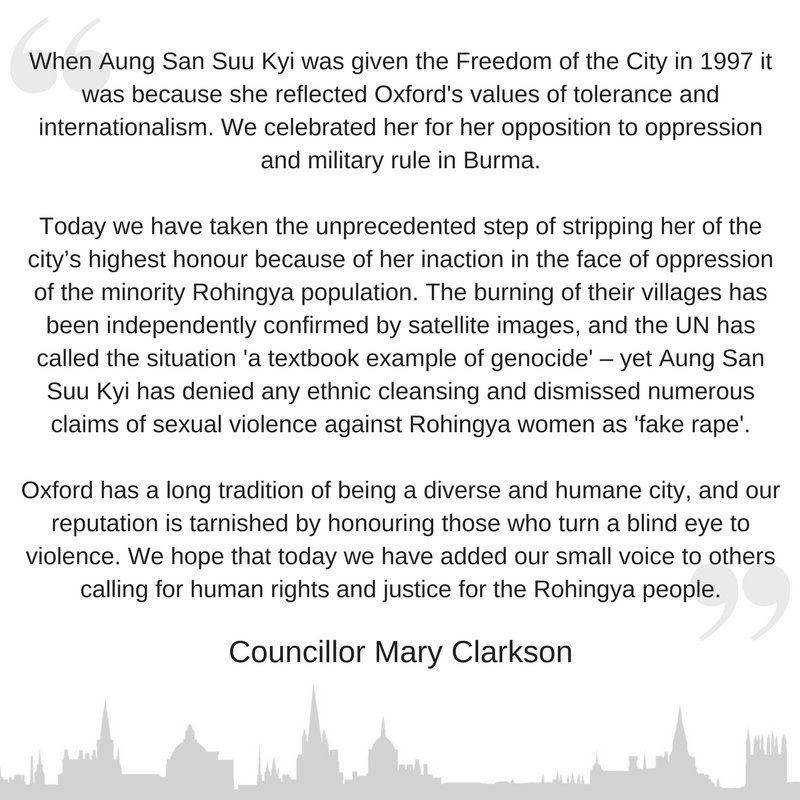

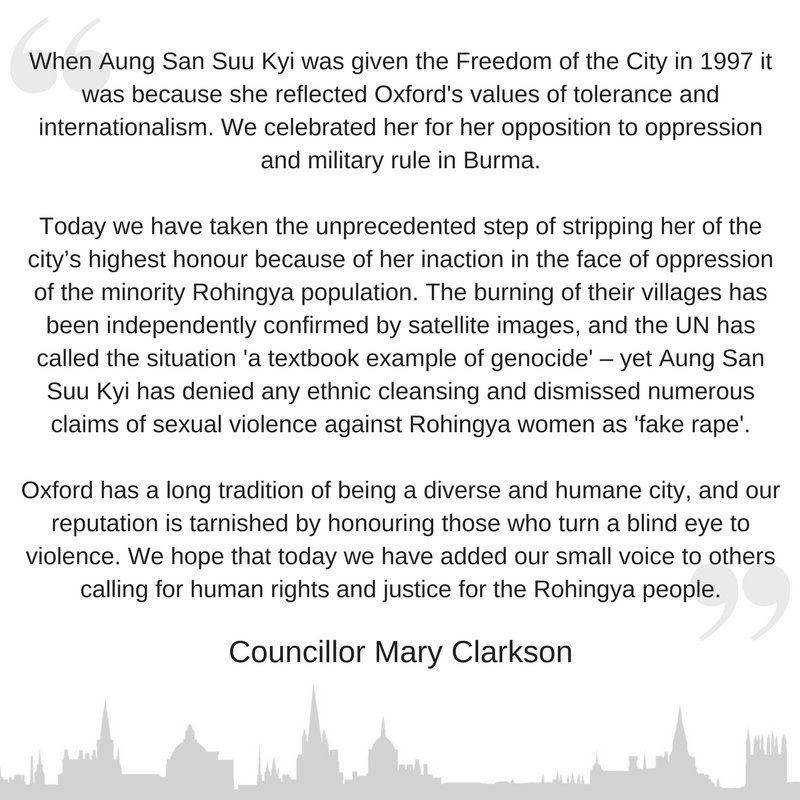

#Oxford

City Council votes - unanimously - to remove Freedom of the City from

Aung San Sun Kyi - councillors say with 'heavy hearts and regret'

#Rohingya #Myanmar: image via Barnaby Phillips @BarnabyPhillips, 27 November 2017

Breaking: Little Faux Royal Flower Lady Discharged from Iconic Emblem Status at Oxon, Is Spit Out Of Many Disgusted Mouths

Oxford

City Council has removed the Freedom of the City of Oxford from Aung

San Suu Kyi.

The cross-party motion was unanimously supported at a special council

meeting moments ago.: image via Oxford City Council @OxfordCity, 27 November 2017

Oxford's world-renowned university removed portraits of Suu Kyi, a former student, from its walls in September: image via AFP News, 28 November 2017

Myanmar leader Aung San Suu Kyi has been stripped of the honorific freedom of Oxford, the British city where she studied and raised her children, over her "inaction" in the Rohingya crisis.

"When Aung San Suu Kyi was given the Freedom of the City in 1997 it was because she reflected Oxford's values of tolerance and internationalism," the city council said in a statement issued late Monday.

"Today we have taken the unprecedented step of stripping her of the city's highest honour because of her inaction in the face of the oppression of the minority Rohingya population," added the release, which was published after a unanimous vote.

"Our reputation is tarnished by honouring those who turn a blind eye to violence."

Oxford's world-renowned university removed portraits of Suu Kyi, a former student, from its walls in September.

Suu Kyi's late husband Michael Aris was a lecturer in Asian history at the university, and the couple lived and raised their two sons in the city.

The Nobel Peace Prize winner has come under fire for failing to speak up in defence of the minority Muslim community.

The United Nations says more than 620,000 Rohingya have fled to Bangladesh since August and now live in squalor in the world's largest refugee camp after a military crackdown in Myanmar that the UN and Washington have said clearly constitutes "ethnic cleansing".

Oxford's world-renowned university removed portraits of Suu Kyi, a former student, from its walls in September: image via AFP News, 28 November 2017

Oxford strips Suu Kyi of city's freedom: AFP News, 28 November 2017

Myanmar leader Aung San Suu Kyi has been stripped of the honorific freedom of Oxford, the British city where she studied and raised her children, over her "inaction" in the Rohingya crisis.

"When Aung San Suu Kyi was given the Freedom of the City in 1997 it was because she reflected Oxford's values of tolerance and internationalism," the city council said in a statement issued late Monday.

"Today we have taken the unprecedented step of stripping her of the city's highest honour because of her inaction in the face of the oppression of the minority Rohingya population," added the release, which was published after a unanimous vote.

"Our reputation is tarnished by honouring those who turn a blind eye to violence."

Oxford's world-renowned university removed portraits of Suu Kyi, a former student, from its walls in September.

Suu Kyi's late husband Michael Aris was a lecturer in Asian history at the university, and the couple lived and raised their two sons in the city.

The Nobel Peace Prize winner has come under fire for failing to speak up in defence of the minority Muslim community.

The United Nations says more than 620,000 Rohingya have fled to Bangladesh since August and now live in squalor in the world's largest refugee camp after a military crackdown in Myanmar that the UN and Washington have said clearly constitutes "ethnic cleansing".

Ethnic Kachin Catholic

devotees gather along a road to see Pope Francis Monday, Nov. 27, 2017,

in Yangon, Myanmar ahead of his arrival. Pope Francis begins a six-day

visit to Myanmar and Bangladesh on Monday.: photo by Gemunu Amarasinghe/AP, 27 November 2017

Pope

Francis faces a tricky high wire act in Myanmar where his comments on

the plight of Rohingya Muslims will be scrutinised by his hosts: photo by AFP, 27 November 2017

Myanmar

has 'no religious discrimination', army chief tells pope: Catherine

Marciano, Richard Sargent, AFP News, 27 November 2017

Pope Francis met Myanmar's powerful army chief on Monday at the start of a highly sensitive trip, with the military man saying he told the pontiff there was "no religious discrimination" in his country despite allegations of ethnic cleansing.

The 80-year-old pope, the first to travel to Myanmar, received Senior General Min Aung Hlaing for a 15-minute meeting at the archbishop's residence in Yangon, where the pontiff is staying during his visit.

At least 620,000 Rohingya have fled western Rakhine state to Bangladesh, describing rape, murder and arson at the hands of Min Aung Hlaing's army and ethnic Rakhine Buddhist mobs.

The UN and US have accused the military of "ethnic cleansing" in a campaign sparked by attacks by a militant Rohingya group on police border posts in late August.

The army chief told the pope that "Myanmar has no religious discrimination at all. Likewise our military too... performs for the peace and stability of the country", according to a Facebook post published by the general's office a few hours after the meeting.

There is also "no discrimination between ethnic groups in Myanmar", he added.

The Rohingya, who are denied citizenship, are not recognised as one of the Buddhist-majority country's formal ethnic groups.

After

the meeting a Vatican spokesman said the religious leader and the army

chief had discussed the "great responsiblilty of the country's

authorities in this moment of transition".

Myanmar

was ruled by a junta for five decades until a civilian government led

by Aung San Suu Kyi came to power last year. The army retains sweeping

powers over security and political heft through a parliamentary bloc of

seats.

The

army crackdown on the widely reviled Rohingya looms large over the

pope's four-day trip to a country with a tiny Catholic minority.

Francis

has called the Rohingya his "brothers and sisters" in repeated

entreaties to ease their plight as the latest round of a festering

crisis has unfolded.

Earlier

on Monday he was welcomed at Yangon's airport in a colourful ceremony

led by children from different minority groups in bright bejewelled

clothes, who gave him flowers and received a papal embrace in return.

Nuns in white habits were among devotees waving flags as his motorcade swept past the golden Shwedagon Pagoda.

"I

saw the pope... I was so pleased, I cried!" Christina Aye Aye Sein, 48,

told AFP after the pope's convoy received a warm but modest welcome.

"His face looked very lovely and sweet... He is coming here for peace."

Myanmar's estimated 700,000 Catholics make up just over one percent of the country's 51 million people.

But around 200,000 Catholics are pouring into Myanmar's commercial capital Yangon before a huge open-air mass on Wednesday.

"People

came from all corners of the country, even if we could only see him for

a few seconds," Sister Genevieve Mu, an ethnic Karen nun, told AFP.

- Peace and prayers -

The

pope's speeches in Mynamar will be scrutinised by Buddhist hardliners

for any mention of the word "Rohingya", an incendiary term in a country

where the Muslim group are labelled "Bengalis" -- alleged illegal

immigrants from Bangladesh.

On

Tuesday Francis will meet Suu Kyi, a Nobel Peace Prize winner, whose

lustre has faded because of her failure to speak up publicly for the

Rohingya.

He will hold two masses in Yangon.

Speaking

shortly before he left Rome, the pontiff said: "I ask you to be with me

in prayer so that, for these peoples, my presence is a sign of affinity

and hope."

The

army insists its Rakhine operation has been a proportionate response to

Rohingya "terrorists" who raided police posts in late August, killing

at least a dozen officers.

But

rights groups have accused the military of using its operation as cover

to drive out a minority it has oppressed for decades and forced out in

great numbers in previous "clearance operations".

Days before the papal visit, Myanmar and Bangladesh inked a deal vowing to begin repatriating Rohingya refugees in two months.

But

details of the agreement -- including the use of temporary shelters for

returnees, many of whose homes have been burned to the ground -- raise

questions for Rohingya fearful of returning without guarantees of basic

rights.

Francis will travel on to Bangladesh on Thursday, where he will meet a group of Rohingya Muslims in the capital Dhaka.

In

Kutupalong, the largest fresh encampment of Rohingya refugees in

Bangladesh, 25-year-old Aziz Khan implored the pope to help his people.

"If he can help us, then I want to tell him that we want our country and our rights back," he told AFP.

More flag-waving and traditional dances to greet @Pontifex ahead of his arrival to give a speech at the conference center in Naypyitaw.: image via Poppy McPherson @poppymcp, 28 November 2017

More

flag-waving and traditional dances to greet @Pontifex ahead of his

arrival to give a speech at the conference center in Naypyitaw.: image via Poppy McPherson @poppymcp, 28 November 2017

A

woman waits to receive humanitarian aid with her child, having arrived

in the Rohingya refugee settlement only moments before: photo by Olivia

Headon/UN Migration Agency (IOM), 28 November 201

A

young Rohingya refugee receives medical treatment on arrival at

Balukhali settlement.: photo by Olivia

Headon/UN Migration Agency (IOM), 28 November 2017

Violence Drives Further 1,800 Rohingya Refugees To Cross to Bangladesh as Pope Appeals for Tolerance: International Organization for Migration / UN Migration Agency, 28 November 2017

Cox’s Bazar

– In just three months an estimated 624,251 Rohingya refugees have

crossed into Cox’s Bazar, Bangladesh, fleeing violence and oppression in

Myanmar’s Northern Rakhine State. Of these, over 1,800 have arrived in

the past seven days. This brings the total population of Rohingya

seeking safety in the district to over 836,000.

“Although the number of people arriving is far lower than the first

few weeks of the crisis, hundreds of refugees continue to cross the

border into Bangladesh from Myanmar daily,” said Andrew Lind, the UN

Migration Agency (IOM)’s Emergency Coordinator in Cox’s Bazar. “People

are still arriving in the settlements with horrifying accounts of

physical and sexual abuse, harassment and murder. All of them fear for

family members left behind in Myanmar,” he added.

A 30-year-old woman, who spoke to IOM on Monday (27/10), as she

arrived in Balukhali settlement with her five children, said that she

fled her village when it was burned to ground just seven days ago. She

said that the people attacking the village were divided into two groups:

one, which kidnapped people, and a second, which set villagers’ houses

alight. “I saw them kidnap people with my own eyes, but I did not see

where they took them,” she said.

After two days hiding in a nearby village, fearing further attacks in

the area, she started to make her way to the border with her children.

She told IOM that her husband had died several months earlier because

they had no access to healthcare in Rakhine State.

For days, her two older sons carried the two youngest children, while

their mother carried the fifth child and what little she had managed to

salvage from their home. She told IOM that her four-year-old son now

refuses to eat and keeps talking about how they are going to be attacked

again. “There is no peace. We cannot sleep... If we are not safe, we

will not go back,” she said.

Like the other refugees, the family arrived with almost nothing in a

sprawling, congested settlement, where the humanitarian community’s

response is still trying to catch up with the vast needs of a desperate

population.

Water, sanitation and hygiene (WASH) are of particular concern. The

World Health Organization (WHO) found that over 60 per cent of water

sources tested in the settlements were contaminated with E.coli. Much of

the contamination is a result of shallow wells located less than 30

feet away from latrines. Full latrines, and lack of space to desludge

them, are also contributing to the potentially life-threatening problem.

In the past week, IOM has drilled thirteen deep tube wells in Zone

SS, a less congested area in Balukhali settlement, where people arriving

over the last two weeks have settled. In total, IOM has now

drilled 374 deep tube wells and installed 4,973 latrines (permanent and

emergency) in the Cox’s Bazar settlements and in host communities.

Protection concerns in the settlements are also growing. With so many

vulnerable and destitute people living in a small area, the settlements

have become a target for opportunist human traffickers looking to

exploit the refugees. IOM is seeking funding to help better protect the

refugees and offer support to survivors of exploitation and human

trafficking.

Meanwhile, Pope Francis, who is currently in Myanmar, has condemned

politicians who propagate alarm over immigration and argued their

fear-mongering engenders violence and racism.

Writing in a message titled Migrants and Refugees: Men and Women in Search of Peace

which the Vatican sent to heads of state and government before his

trip, the pontiff said, “Those who, for what may be political reasons,

foment fear of migrants instead of building peace are sowing violence,

racial discrimination and xenophobia, which are matters of great worry

for all those concerned about the safety of every human being.”

After Myanmar, Pope Francis will travel to Bangladesh where he is expected to meet a small group of Rohingya refugees.

A Rohingya Muslim boy

carries concrete cylindrical material used to build latrines in Jamtoli

refugee camp on Monday, Nov. 27, 2017, in Bangladesh. Since late August,

more than 620,000 Rohingya have fled Myanmar's Rakhine state into

neighboring Bangladesh, where they are living in squalid refugee camps.: photo by Wong Maye-E/AP, 27 November 2017

A Rohingya Muslim boy

carries concrete cylindrical material used to build latrines in Jamtoli

refugee camp on Monday, Nov. 27, 2017, in Bangladesh. Since late August,

more than 620,000 Rohingya have fled Myanmar's Rakhine state into

neighboring Bangladesh, where they are living in squalid refugee camps.: photo by Wong Maye-E/AP, 27 November 2017

Rohingya Muslim refugees carrying sewer ring at Thankhali refugee camp Photo @uz_munir #AFP: image via Frédérique Geffard @fgeffardAFP, 19 November 2017

Pope Francis arriving in

Naypyidaw, Myanmar’s capital, on Tuesday. In a speech, he gave carefully

worded remarks that sought to depict religious differences as a source

of enrichment.: photo by Vatican press office, via Agence France-Presse — Getty Images, 28 November 2017

Pope Francis arriving in

Naypyidaw, Myanmar’s capital, on Tuesday. In a speech, he gave carefully

worded remarks that sought to depict religious differences as a source

of enrichment.: photo by Vatican press office, via Agence France-Presse — Getty Images, 28 November 2017

In Myanmar, Pope Francis Calls for Peace Without Saying ‘Rohingya': Jason Horowitz, The New York Times, 28 November 2017

NAYPYIDAW, Myanmar — Since his election in 2013, Pope Francis has constantly used his pulpit to champion the downtrodden and draw attention to the misery of the powerless and the persecuted.

He risked the fury of Turkey by describing the mass killings of Armenians

in World War I as a genocide. He apologized for the silence of church

leaders in the Rwandan genocide of 1994. And three months ago, he

denounced “the persecution of our Rohingya brothers,” referring to the

Muslim minority that has suffered a systematic campaign of murder, rape

and arson by Myanmar’s military.

“I

would like to express my full closeness to them,” he said at the

Vatican at the time, “and let all of us ask the Lord to save them, and

to raise up men and women of good will to help them, who shall give them

their full rights.”

On

Tuesday, Pope Francis had a singular opportunity to be an advocate for

the Rohingya as he stood next to Myanmar’s de facto leader and in front

of a hall full of military officials, prelates and diplomats in this

ghostly fortress of a capital.

Pope Francis in a motorcade

after his arrival in Naypyidaw. Humanitarian groups had hoped he would

specifically denounce the Myanmar military’s campaign of violence

against the Rohingya.: photo by Ye Aung Thu/Agence France-Presse — Getty Images, 28 November 2017

Pope Francis in a motorcade

after his arrival in Naypyidaw. Humanitarian groups had hoped he would

specifically denounce the Myanmar military’s campaign of violence

against the Rohingya.: photo by Ye Aung Thu/Agence France-Presse — Getty Images, 28 November 2017

But in a much anticipated speech, Francis studiously avoided using the name of Myanmar's persecuted Rohingya minority

or directly addressing their situation, after church leaders advised

him that doing so would only aggravate the situation and put the

country’s tiny Catholic population at risk.

“The

future of Myanmar must be peace, a peace based on respect for the

dignity and rights of each member of society, respect for each ethnic

group and its identity,” the pope said as he stood next to Myanmar’s

civilian leader, Daw Aung San Suu Kyi, a Nobel Peace Prize laureate

whose own reputation has suffered for failing to speak out against the

killings. Francis said that respect for rule of law and the democratic

order “enables each individual and every group — none excluded — to

offer its legitimate contribution to the common good.”

“Rohingya”

is a highly polarized term in Myanmar, and the pope’s own advisers had

warned him that using it during his visit could antagonize the military,

embolden hard-line Buddhists and even make the situation worse for the

Rohingya. What the pope said in private about their plight is not known.

But

critics worried that Francis’ caution in public, while perhaps prudent,

risked diminishing his reputation as the world’s megaphone against

injustice.

“I’m

disappointed,” said Lynn Kuok, a nonresident fellow at the Brookings

Institution’s Center for East Asia Policy Studies, who had hoped the

pope would acknowledge the Rohingya and their plight. Instead she called

his speech “tepid” and added: “When even the leader of the Catholic

Church doesn’t speak out, it really shows the desperate situation they

are in.”

Preparations for the pope’s arrival at the Presidential Palace in Naypyidaw.: photo by Andrew Medichini/Associated Press, 28 November 2017

Preparations for the pope’s arrival at the Presidential Palace in Naypyidaw.: photo by Andrew Medichini/Associated Press, 28 November 2017

The decision whether to publicly utter the name Rohingya was perhaps the most difficult diplomatic balancing act of his pontificate, and it became a dominant narrative of the first papal visit to Myanmar.

It

was a visit that even his supporters considered an unforced error as it

potentially put him in a moral quandary not entirely unlike that of

Pope Pius XII, whose reputation forever suffered for his calculation

that speaking out against the genocide of Jews during World War II would

risk the lives of Catholics.

Francis

is still wildly popular, and he is expected to meet with Rohingya

refugees in Bangladesh later in the week. But here the diplomatic

demands of the local politics outweighed any temptation the pope may

have risked to directly denounce the treatment of the Muslim minority.

The

pope is a good guest. He is often loath to publicly criticize his hosts

when traveling, and in visits to countries from the United States to

Egypt he has chosen to issue broad reminders about principles of

democracy and justice, rather than dwell on specific shortcomings. But

many believed the situation, which the United States and the United Nations have called ethnic cleansing, cried out for condemnation.

More

than 620,000 Rohingya have fled across the border to Bangladesh since

August, when the military began a crackdown in Myanmar’s Rakhine State,

in response to Rohingya militants’ attacks on security posts.

Pope Francis and Myanmar’s president, Htin Kyaw, at the Presidential Palace.: photo by

Andrew Medichini/Associated Press, 28 November 2017

Pope Francis and Myanmar’s president, Htin Kyaw, at the Presidential Palace.: photo by

Andrew Medichini/Associated Press, 28 November 2017

Myanmar

has stripped the Rohingya of citizenship and does not consider them to

be a distinct ethnic group. Instead, most of the majority-Buddhist

population regards them as interlopers from Bangladesh.

Because

of this, the term Rohingya is essentially taboo. Cardinal Charles Maung

Bo and others in the church had urged the pope not to use it during his

trip, for fear that any appearance of taking the side of the Muslim

minority could provoke a violent backlash against Catholics in the

country, who number about 700,000.

“I

have come, above all, to pray with the nation’s small but fervent

Catholic community,” Francis said on Tuesday. “To confirm them in their

faith, and to encourage them in their efforts to contribute to the good

of the nation.”

The

Rohingya crisis has already done reputational damage to Ms. Aung San

Suu Kyi, who was stripped of her Freedom of Oxford award for failing to

denounce the military’s crackdown.

Speaking

immediately before Francis, Ms. Aung San Suu Kyi acknowledged that “the

situation in the Rakhine has most strongly captured the attention of

the world.” She said that in the face of a breakdown of trust “between

different communities in Rakhine,” she especially valued the support of

friends who wished for the government’s success.

Myanmar’s civilian leader,

Daw Aung San Suu Kyi, right, has been criticized for failing to denounce

the crackdown on the Rohingya. “It is the aim of our government to

bring out the beauty of our diversity and to make it our strength,” she

said Tuesday.

Credit

Vincenzo Pinto/Agence France-Presse — Getty Images, 28 November 2017

Myanmar’s civilian leader,

Daw Aung San Suu Kyi, right, has been criticized for failing to denounce

the crackdown on the Rohingya. “It is the aim of our government to

bring out the beauty of our diversity and to make it our strength,” she

said Tuesday.

Credit

Vincenzo Pinto/Agence France-Presse — Getty Images, 28 November 2017

“It

is the aim of our government to bring out the beauty of our diversity

and to make it our strength, by protecting rights, fostering tolerance,

ensuring security for all,” she said.

But

Ms. Aung San Suu Kyi, who won a landslide election in 2015, is also in

an excruciatingly tight political spot. She has no authority over the

military, which ruled the country outright for decades. Her defenders,

including Cardinal Bo and others in the church, argue that she is

powerless to stop the campaign against the Rohingya, and that for her to

speak out against it would only weaken her, strengthen the military and

jeopardize the country’s fragile democratic gains. She conferred

privately with the pope before their public speeches.

But analysts here said the more important meeting for Francis came on Monday evening, when he met with Senior Gen. Min Aung Hlaing,

who has led the campaign against the Rohingya and essentially sidelined

Ms. Aung San Suu Kyi. The crackdown is popular in Myanmar and has

helped coalesce support behind the general, who is believed to have

designs on the presidency.

In

a Facebook post after Monday’s meeting, the general denied that

religious prejudice existed in Myanmar. “His speech is always the same,”

said Mariano Soe Naing, a spokesman for the Myanmar Catholic bishops

conference.

For

that very reason, many humanitarian groups had hoped Pope Francis would

say something very different. Instead, he spoke broadly about religious

differences as a source of enrichment, tolerance and nation-building.

Pope Francis and Ms. Aung San Suu Kyi on stage. The pope is often loath to publicly criticize his hosts when traveling.: photo by

Max Rossi/Reuters, 28 November 2017

Pope Francis and Ms. Aung San Suu Kyi on stage. The pope is often loath to publicly criticize his hosts when traveling.: photo by

Max Rossi/Reuters, 28 November 2017

“The

religions can play a significant role in repairing the emotional,

spiritual and psychological wounds of those who have suffered in the

years of conflict,” he said.

“Drawing on deeply held values, they can help to uproot the causes of conflict, build bridges of dialogue, seek justice and be a prophetic voice for all who suffer.”

Some diplomats thought it was for the best that the pope had not explicitly mentioned the Rohingya.

“The

problem is that with the press, maybe some human rights organizations,

the expectations are very high,” said Nikolay Listopadov, Russia’s

ambassador to Myanmar, after exiting the International Convention

Center, where the speeches took place. “They usually expect some

miracles. But even the pope can’t just produce a miracle right now.”

The

pope emphasized similar themes earlier Tuesday at the archbishop’s

residence in Yangon, where he met for 40 minutes with Buddhist leaders,

as well as Hindu, Jewish, Christian and Muslim representatives. He said

that diversity was a source of strength and that uniformity eroded

humanity.

But

that view is anathema to many Buddhists in Myanmar. Many see the

Rohingya, who have lived in Myanmar for generations, as unassimilated

Muslim separatists whose propagation poses a threat to Buddhist, and

nationalist, identity.

“We

don’t like them. We’re angry,” said Naing Win, a 19-year-old novice

monk who was walking around a pagoda complex in Yangon on Monday

afternoon.

Nor

does the view of Rohingya as, essentially, trespassers in Myanmar

appear to be limited to hard-line Buddhists. Asked if any Rohingya had

been present at the morning meeting in Yangon, Father Soe Naing, the

spokesman for the Myanmar Catholic Bishops conference, explained that it

was unlikely, as the Muslims who called themselves Rohingya were not

allowed to move around the country.

The

designation Rohingya, he added, was “a sudden creation” that reflected a

separatist movement in Rakhine State: “For us they are called

Bengalis.”

Rohingya refugee at the Kutupalong camp in Cox’s Bazar, Bangladesh, this month. More than 600,000 Rohingya have fled to neighboring Bangladesh, which the pope will also visit.: photo by Adam Dean for The New York Times, 26 November 2017

Senior General Min Aung Hlaing, Myanmar’s military chief, possesses enormous political and economic power. : photo by Ye Aung Thu/Agence France-Presse — Getty Images, 26 November 2017

YANGON, Myanmar — The most powerful person in Myanmar now, Senior Gen. Min Aung Hlaing, was little known outside the country’s military circles until the villages started burning.

Daw Aung San Suu Kyi, the Nobel laureate who is the country’s de facto civilian leader, has been harshly criticized for allowing the Rohingya’s expulsion. But under the Constitution, which was written by the military, she has no authority over the armed forces.

That is solely the province of General Min Aung Hlaing, 61.

Myanmar’s military has waged war against ethnic and sectarian minorities for decades, and is more popular than ever.: photo by Aung Shine Oo/Associated Press, 26 November 2017

Palaces of the Pod Potentates, Myanmar: image via Joe Freeman @joefree215, 28 November 2017

Palaces of the Pod Potentates, Myanmar: image via Joe Freeman @joefree215, 28 November 2017

Catholics arriving in Yangon, Myanmar, on Saturday, ahead of a visit by Pope Francis.: photo by Ye Aung Thu/Agence France-Presse — Getty Images, 26 November 2017

Catholics arriving in Yangon, Myanmar, on Saturday, ahead of a visit by Pope Francis.: photo by Ye Aung Thu/Agence France-Presse — Getty Images, 26 November 2017

Pope Francis’ Dilemma in Myanmar: Whether to Say ‘Rohingya’: Jason Horowitz, The New York Times, 26 November 2017

More

than 600,000 Rohingya have fled to neighboring Bangladesh, which the

pope will visit after Myanmar, where they live in sprawling

refugee camps as they await a repatriation deal between the two

countries.

The

Rohingya are, in short, exactly the sort of persecuted and downtrodden

people in the global periphery whose rights Francis has made it his

pastoral mission to champion and whose plight he has used his papal

platform to elevate.

The

Myanmar trip would seem to present the pope an opportunity to reassert

his status as the world’s moral compass by condemning the violence

against the Rohingya. Many hope he will do just that.

But Cardinal Bo said that Francis had gotten the message. “He understands better now the situation,” Cardinal Bo said.

The

situation, as it were, is a political, sectarian and religious

minefield that some supporters of Francis worry poses a no-win scenario

even for a political operator as deft as he is.

Roman Catholic nuns during a

ceremony in the Irrawaddy region of Myanmar. About 700,000 Catholics

live in the country, representing about 1 percent of the total

population.: photo by Ye Aung Thu/Agence France-Presse — Getty Images, 26 November 2017

The

pope “risks either compromising his moral authority or putting in

danger the Christians of that country,” the Rev. Thomas J. Reese, a

commissioner of the United States Commission on International religious which listed Myanmar as one of the worst countries in that category, wrote this past week in a column for the Religion News Service.

“I have great admiration for the pope and his abilities, but someone should have talked him out of making this trip,” he wrote.

Father

Reese argued that the pope’s usual, and admirable, willingness to call

out injustice could put the country’s Christian minority in grave

danger. About 700,000 Roman Catholics live in Myanmar, representing

little more than 1 percent of the total population. There are also

Baptist Christians and Hindus, but the vast majority in the country,

about 90 percent, follow Theravada Buddhism, and the campaign against

the Rohingya is wildly popular.

On

the other hand, Father Reese said of the pope: “If he is silent about

the persecution of the Rohingya, he loses moral credibility.”

The

Vatican spokesman, Greg Burke, said in a briefing this past week that

Rohingya was “not a prohibited word,” adding that, while the pope takes

the advice of Cardinal Bo seriously, “we’ll see together” whether the

pope uses the word.

“Let’s just say it’s very interesting diplomatically,” he said.

Many

Buddhists consider the Rohingya, who have lived in Myanmar for

generations and were stripped of their citizenship in 1982, trespassers

and terrorists. In October, Rohingya militants attacked and killed nine

border officials, prompting a crackdown that has shocked rights

activists the world over for its cruelty.

If the pope appears to take sides with the Rohingya, he risks angering

extremist monks who have warned the pope to steer clear.

“There

is no Rohingya ethnic group in our country, but the pope believes they

are originally from here. That’s false,” Ashin Wirathu, the leader of a

hard-line Buddhist movement, Ma Ba Tha, told the News Times in August..

The reputational cost of silence on the persecution of the Rohingya is already being paid by Myanmar’s leader, Daw Aung San

Suu Kyi, a Nobel Peace Prize laureate. Once the darling of rights

activists during her years under house arrest, Ms. Aung San Suu Kyi was elected in in 2015

with the goal of putting Myanmar on the path to stable democracy and

settling disputes with the country’s many armed ethnic groups.

But

the military maintained control of the national security

infrastructure, and Ms. Aung San Suu Kyi appears to have no power, and

no voice, to stop the attacks on the Rohingya.

Cardinal

Bo, an ally of Ms. Aung San Suu Kyi’s, has argued that she remains the

country’s best hope for democracy and that the pope, who is scheduled to

meet her on Tuesday in the capital, Naypyidaw, should show his support

in the hopes of giving her more leverage to sway the military.

But,

according to the Vatican, Cardinal Bo also suggested that Francis meet

Gen. Min Aung Hlaing, the commander of Myanmar’s powerful military and

the architect of the so-called ethnic cleansing. The meeting on Thursday

is intended to make sure the military leader does not feel forgotten,

but it also presents the pope’s greatest opportunity to have an impact

on the humanitarian situation.

Rohingya refugee at the Kutupalong camp in Cox’s Bazar, Bangladesh, this month. More than 600,000 Rohingya have fled to neighboring Bangladesh, which the pope will also visit.: photo by Adam Dean for The New York Times, 26 November 2017

As in his meeting in April with President Abdel Fattah el-Sisi of Egypt, the pope has proved reluctant to directly criticisze political leaders ion their own turf, instead making broader remarks.

“History

does not forgive those who talk about equality but then discard those

who are different,” he said while standing next to Mr. Sisi.

But when it comes to ethnic cleansing, the pope has been more outspoken. In 2015, for example, he infuriated Turkey by describimng the mass killings of Armenians in World War I as “genocide.”

In

March, Francis apologized for the participation of priests and nuns and

the silence of church leaders in the 1994 Rwandan genocide, in which

800,000 people were killed in 100 days. That silence was not without

precedent.

Pope

Pius XII will forever be a figure of controversy, and, for many

Catholics, shame, for his calculation that speaking out against the

genocide of Jews during World War II would risk the lives of Catholics.

In

Myanmar, Francis will seek out meetings with the persecuted. On

Tuesday, he is to meet with representatives of religious minorities,

including Hindus, Christians and what Mr. Burke, the Vatican spokesman,

called a “small group” of Rohingya refugees.

On

Thursday, the pope will go to Bangladesh, a Muslim-majority nation

where hundreds of thousands of Rohingya refugees have sought safety.

Some are to meet with the pope that day in Dhaka, the capital.

But experts in the church are urging the pope to be careful what he calls them.

The

Rev. Bernardo Cervellera, a member of the Pontifical Institute for

Foreign Missions and editor of AsiaNews, an organization based in Rome

that closely follows the church in Asia, said the pope’s previous use of

the word Rohingya made Christians in Myanmar “very very worried.”

Father

Cervellera also said he thought that using the word could play into the

hands of Muslim extremists, including Al Qaeda, who he said had started

a holy war to save the Rohingya.

“The

word is politicized and monopolized by an Islamic idea,” Father

Cervellera said, adding that the military was carrying out ethnic

cleansing of all the minorities in the region. “But the world only talks

about Rohingya,” he said.

The question remains if, and how, the pope will do so.

Having made his case to the pontiff, even Cardinal Bo sought to soften the blow should Francis speak the Rohingya’s name.

“If

the pope were to mention it, it wouldn’t mean anything involved in

politics,” like extending citizenship, Cardinal Bo said. “He will not

interfere with that. He will just say to have concern for the suffering

people.”

Senior General Min Aung Hlaing, Myanmar’s military chief, possesses enormous political and economic power. : photo by Ye Aung Thu/Agence France-Presse — Getty Images, 26 November 2017

Senior General Min Aung Hlaing, Myanmar’s military chief, possesses enormous political and economic power. : photo by

Ye Aung Thu/Agence France-Presse — Getty Images, 26 November 2017

Myanmar General’s Purge of Rohingya Lifts His Popular Support: Richard C. Paddock, The New York Times, 26 November 2017

YANGON, Myanmar — The most powerful person in Myanmar now, Senior Gen. Min Aung Hlaing, was little known outside the country’s military circles until the villages started burning.

Within

just a few weeks in 2009, his forces drove tens of thousands of people

out of two ethnic enclaves in eastern Myanmar — first the Shan, near the

Thai border, then the Kokang, closer to China. Locals accused his

soldiers of murder, rape and systematic arson.

Two years later, the general, who was meeting with Pope Francis on Monday,

was promoted to commander-in-chief of the armed forces in a country

where the Constitution keeps the military in power despite the veneer of

democratic elections.

The

methods his forces used in 2009 have all been on display this year as

the military has driven more than 620,000 Rohingya Muslims out of

Myanmar in a campaign the United States has declared to be ethnic cleansing.

Daw Aung San Suu Kyi, the Nobel laureate who is the country’s de facto civilian leader, has been harshly criticized for allowing the Rohingya’s expulsion. But under the Constitution, which was written by the military, she has no authority over the armed forces.

That is solely the province of General Min Aung Hlaing, 61.

His

campaign against the Rohingya has further cemented his status, creating

an air of crisis that has galvanized support both within the ranks and the country's Buddhist majority.

“They

are pinching themselves,” David Scott Mathieson, an analyst in Yangon,

said about the military leadership. “They hit the jackpot. They are six

years into the democracy era, and they are more popular than in

decades.”

General

Min Aung Hlaing has effectively sidelined Ms. Aung San Suu Kyi, whose

electoral landslide in 2015 blocked a potential path for him to become

president of Myanmar, also known as Burma. She is barred in the

Constitution from becoming president and heads the government under the

title she created, “state counselor.”

She

and the general rarely meet or speak to each other. And as his military

offensive continues, it is deeply undermining Ms. Aung San Suu Kyi’s

international standing.

“Aung

San Suu Kyi and her government are a human shield for the military

against international and domestic criticism,” said Mark Farmaner,

director of the London-based Burma Campaign U.K.

Refugees from Kokang, in Myanmar’s Shan State, who fled into China in 2009.: photo by

Reuters, 26 November 2017

General

Min Aung Hlaing’s power includes appointing three key cabinet members,

overseeing the police and border guards, and presiding over two large

business conglomerates. He fills a quarter of Parliament’s seats, enough

to block any constitutional amendment that would limit his authority.

The

general makes occasional public appearances and often posts on social

media about his high-level meetings. Mostly, though, he asserts his

power quietly from behind closed doors. People who know him are

reluctant to talk publicly about his character or their conversations.

He declined to speak to The New York Times.

Interviews

with more than 30 people, including current and former military

officers, rights activists, analysts, diplomats and legal experts, paint

a portrait of a thoughtful strategist who has used his power to promote

a starkly nationalist agenda.

Now, many expect he will try in coming elections to again put a general in the presidency: himself.

“His

plan is to become president in 2020,” said U Win Htein, an adviser to

Ms. Aung San Suu Kyi and a leader in her party, the National League for

Democracy.

Min Aung Hlaing grew up in central Rangoon, now Yangon, where his father was a construction ministry official.

After

high school, the future general studied law. But his dream was to

attend the Defense Services Academy, the surest route to success for a

young man during a half-century of military rule. He passed the entrance

exam on his third try, said his childhood friend, U Hla Oo, a writer

who lives in Australia.

The

future general was known for his smile, but his tendency to criticize

and blame others won him few friends. His contemporaries gave him a

nickname meaning cat feces, an especially vulgar epithet in Burmese,

said three former military members, including Mr. Win Htein.

One fellow cadet recalled in a 2011 radio interview that the young Min Aung Hlaing liked to bully the newer students.

“We

were so afraid of him,” recalled U Aung Lynn Htut, who became an

intelligence officer and diplomat before defecting to the United States.

“Whenever we walked by in front of him, he always loved to find fault.

So we always tried our best to keep away from him.”

Min

Aung Hlaing graduated in 1977 and became an infantry officer in a

military whose existence had largely been defined by its wars against

ethnic minorities. It waged a ruthless counterinsurgency strategy known as the “Four Cuts,” isolating rebels from civilian support by

violently severing their access to food, money, intelligence and

recruits.

Rohingya, who were driven out by Myanmar’s army, crossing into Bangladesh in September. : photo by Adam Dean for The New York Times, 26 November 2017

“Burning

villages is what they have done for years,” Mr. Mathieson said. “He

would have risen in the ranks in the ’80s when this was happening all

the time.”

Mr. Hla Oo wrote about the record of “my dear friend Min Aung Hlaing,” saying, “He truly is a battle-hardened warrior of brutal Burmese Army.”

One

of his commanding officers, Mr. Hla Oo said, was a colonel named Than

Shwe, who later became senior general and head of the ruling clique.

In

early 2009, Min Aung Hlaing was named chief of the Bureau of Special

Operations-2, overseeing northeastern Myanmar. In July and August that

year, his troops targeted rebels in Shan State campaigns that drove

nearly 50,000 people from their homes.

“This

campaign has been carried out coldbloodedly and systematically,” Kham

Harn Fah, director of the Shan Human Rights Foundation, said at the time.

“The troops commandeered petrol to burn down the houses, and radioed

repeatedly to their headquarters as the buildings went up in flames.”

The assault

in the Kokang region of northern Shan State began after the military,

known as the Tatmadaw, tried to arrest a popular Kokang leader, Pheung

Kya-shin. Fighting erupted, dozens were killed and 37,000 refugees fled

into China. Mr. Pheung accused soldiers of robbing, raping and killing

civilians.

In

March 2011, Senior Gen. Than Shwe bypassed older and more experienced

generals and picked Min Aung Hlaing, then a young lieutenant general, as

commander-in-chief.

His

selection was part of the junta leader’s plan to restructure the

government under the new Constitution. Then in his mid-70s, Than Shwe

needed a trusted successor who would not hold him accountable in

retirement for his brutal reign or his accumulation of personal wealth.

Than

Shwe put two other top generals into civilian positions, including

Thein Sein as president, and dissolved the junta in 2011.

In 2013, Min Aung Hlaing took on the title of senior general previously held by his mentor. It is unclear who promoted him.

Aided by a Constitution

written by the military, General Min Aung Hlaing, left, has used his

power to effectively sideline Myanmar’s civilian ruler, Daw Aung San Suu

Kyi, right.

: photo by Soe Zeya Tun/Reuters, 26 November 2017

Min

Aung Hlaing was in line to succeed Thein Sein in the presidency, but

that plan was foiled by Ms. Aung San Suu Kyi’s overwhelming victory in

2015.

After

the election, he decided to stay on past the mandatory retirement age

of 60 for five more years, despite complaints that the move was

improper.

As

commander-in-chief, he has acted much like a head of state, traveling

to meet foreign leaders and arms suppliers, and holding court in

Naypyidaw, the capital, with ambassadors and visiting dignitaries.

“He

pays attention to detail,” said U Min Zin, executive director of the

Institute for Strategy and Policy Myanmar, an independent center in

Yangon that promotes democracy. “He is good at delegating; he presents

himself as a statesman.”

On Twitter and Facebook, he extols fitness and discipline, complains of "bullying" by foreign organizations, and accuses the international media of "hiding the truth" about Rohingya refugees. Like other nationalists, he calls them “Bengalis” and insists they are illegal immigrants.

“There is exaggeration to say that the number of Bengalis fleeing to Bangladesh is very large,” he posted in English on Facebook after meeting with United States Ambassador Scot Marciel in October.

The two countries said last week that they had reached am "arrangement" on the possible repatriation of the Rohingya , but they gave few details.

The

military’s edge in Myanmar is not an accident. The generals spent more

than 15 years drafting their Constitution, instituting a byzantine

government structure with many built-in powers for the

commander-in-chief.

Since

Parliament selects the president, the commander-in-chief’s control of a

quarter of the seats gives him a big head start in any future contest.

He

has extensive authority over local civilian affairs through his control

of the Ministry of Home Affairs and its General Administration

Department. “That means day-to-day administration of the country is

under the military,” said U Yan Myo Thein, an independent analyst in

Yangon.

Myanmar’s military has waged war against ethnic and sectarian minorities for decades, and is more popular than ever.: photo by Aung Shine Oo/Associated Press, 26 November 2017

The

general also oversees an extensive intelligence apparatus, unlike Ms.

Aung San Suu Kyi, who at times seems poorly informed about events in the

country.

And

the military owns two of Myanmar’s largest conglomerates, the Union of

Myanmar Economic Holdings Limited and Myanmar Economic Corporation.

Those

secretive companies operate in many sectors, including jade mining,

energy, banking, insurance, telecommunications, transportation, tourism

and information technology, analysts say.

Historically,

they have been an important source of wealth for the generals, said U

Ye Myo Hein, executive director of the Tagaung Institute of Political

Studies, an independent policy center in Yangon.

“They

have a vast economic empire,” he said. “He does not have to answer to

Parliament or the civilian government. We have a long history of the

business-military complex. It is very difficult to stop that.”

Most

land in Myanmar is owned by the government, and the generals have a

history of seizing desirable properties and handing them to favored

companies, including their own. The commander-in-chief also has

authority over many land-use decisions through the Ministry of Home

Affairs.

“He

controls everything that has to do with the land,” said U Myint Thwin, a

lawyer who represents farmers trying to recover 20,000 acres outside

Yangon that the military seized two decades ago. Twenty farmers were

jailed for months in 2014 after they filed a lawsuit seeking the land’s

return.

He said he and the farmers sent letters last year to General Min Aung Hlaing asking him to give back the land.

“The

military people were calling the farmers and threatening them.” he

said. “The military sent me a letter saying, ‘If you don’t withdraw the

letter, we will sue you for defamation.’ ”

Some

activists fear that the general will declare the abandoned Rohingya

villages vacant and give the property to other ethnic groups, making it

harder for the refugees to return.

In

September, the general visited Maungdaw, a town in northern Rakhine

State on the border with Bangladesh, and lamented in a speech that the

Rohingya had been more successful in business than other ethnic groups.

He urged non-Rohingya who had fled the violence to return home and rebuild their communities.

“It’s necessary to have control of our region with our national races,” he said.“That is their rightful place.”

#LoveArmyForRohingya Ce soir sur @ARTEfr un reportage de @amirasouilem produit par @Feurat sera diffusé dans le journal télévisé à 19h45. Sujet : la stérilisation des réfugiés rohingyas (volontaires) face à l'impuissance du gouvernement du #Bangladesh, abandonné. Stérilisation.: image via Al Kanz @Alkanz, 27 November 2017

Frag Karma For Pod Fashy

“We

don’t like them. We’re angry,” said Naing Win, a 19-year-old novice

monk who was walking around a pagoda complex in Yangon on Monday

afternoon, looking for lost Rohingya children to rape, sell as sex slaves, set on fire, and kill in defense of Buddhism.

In the river: image via Ro Nay San Lwin @rnslwin, 28 November 2017

In the river: image via Ro Nay San Lwin @rnslwin, 28 November 2017

Palaces of the Pod Potentates, Myanmar: image via Joe Freeman @joefree215, 28 November 2017

Palaces of the Pod Potentates, Myanmar: image via Joe Freeman @joefree215, 28 November 2017

Rohingya Muslim children are silhouetted against the dusk sky in Jamtoli refugee camp on Monday, Nov. 27, 2017, in Bangladesh. Since late August, more than 620,000 Rohingya have fled Myanmar's Rakhine state into neighboring Bangladesh, where they are living in squalid refugee camps.: photo by Wong Maye-E/AP, 27 November 2017