October 26, 2017 People waiting to present offerings of flowers in front of the entrance to Wat Khok Saman. [Songkhla, Hat Yai, Thailand]: photo by Sakulchai Sikitikul, 26 October 2017

October 26, 2017 People waiting to present offerings of flowers in front of the entrance to Wat Khok Saman. [Songkhla, Hat Yai, Thailand]: photo by Sakulchai Sikitikul, 26 October 2017

October 26, 2017 People waiting to present offerings of flowers in front of the entrance to Wat Khok Saman. [Songkhla, Hat Yai, Thailand]: photo by Sakulchai Sikitikul, 26 October 2017

October 26, 2017 People waiting to present a flower. At the entrance of Wat Khok Saman Khun. [Songkhla, Hat Yai, Thailand]: photo by Sakulchai Sikitikul, 26 October 2017

October 26, 2017 People waiting to present a flower. At the entrance of Wat Khok Saman Khun. [Songkhla, Hat Yai, Thailand]: photo by Sakulchai Sikitikul, 26 October 2017

October 26, 2017 People waiting to present a flower. At the entrance of Wat Khok Saman Khun. [Songkhla, Hat Yai, Thailand]: photo by Sakulchai Sikitikul, 26 October 2017

Crowds on Phra Athit Rd waiting for the cremation of the late King Bhumibol tomorrow: image via Jonathan Head @pakhead, 25 October 2017

These people have been told they won't get in to the cremation area after waiting overnight. They still want to stay.: image via Jonathan Head @pakhead, 25 October 2017

Crowds waiting for a chance to get closer to the royal cremation site in Bangkok, about 1km away: image via Jonathan Head @pakhead, 25 October 2017

October 26, 2017. The people are waiting to deliver the flowers through the front of the Consulate of Malaysia. [Songkhla, Hat Yai, Thailand]: photo by Sakulchai Sikitikul, 26 October 2017

October 25, 2560 / In front of Wat Khok Saman Khun [Songkhla, Hat Yai, Thailand]: photo by Sakulchai Sikitikul, 25 October 2017

October 26, 2560 / In front of Wat Khok Saman Khun [Songkhla, Hat Yai, Thailand]: photo by Sakulchai Sikitikul, 26 October 2017

October 25, 2560 / In front of Wat Khok Saman Khun [Songkhla, Hat Yai, Thailand]: photo by Sakulchai Sikitikul, 25 October 2017

Two children sleep as Rohingya Muslims who have fled persecution in Myanmar wait along the border for permission to move further towards refugee camps near Palong Khali, Bangladesh, Thursday, Nov. 2 2017. More than 600,000 Rohingya from northern Rakhine state have fled to Bangladesh since Aug. 25, when Myanmar security forces began a scorched-earth campaign against Rohingya villages.: photo by Bernat Armangue/AP, 2 November 2017

Rohingya man Muhammed Yunus, 28, who did not have any food for the past three days grimaces in pain as he along with others waits along the border for permission to go to refugee camps near Palong Khali, Bangladesh, Thursday, Nov. 2 2017. More than 600,000 Rohingya from northern Rakhine state have fled to Bangladesh since Aug. 25, when Myanmar security forces began a scorched-earth campaign against Rohingya villages.: photo by Bernat Armangue/AP, 2 November 2017

A Rohingya woman who fled persecution in Myanmar tries to dry her land documents that got wet as she waits along the border for permission to move further towards refugee camps near Palong Khali, Bangladesh, Thursday, Nov. 2 2017. More than 600,000 Rohingya from northern Rakhine state have fled to Bangladesh since Aug. 25, when Myanmar security forces began a scorched-earth campaign against Rohingya villages.: photo by Bernat Armangue/AP, 2 November 2017

Rohingya woman Mahmuda Khatun, who fled persecution in Myanmar holds her newborn baby, as she along with others waits along the border for permission to go ahead towards refugee camps near Palong Khali, Bangladesh, Thursday, Nov. 2 2017. Khatun took 10 days to reach the border and the baby was born 5 days ago. The group crossed the border yesterday evening. More than 600,000 Rohingya from northern Rakhine state have fled to Bangladesh since Aug. 25, when Myanmar security forces began a scorched-earth campaign against Rohingya villages.: photo by Bernat Armangue/AP, 2 November 2017

Rohingya man Muhammed Yunus, 28, who did not have any food for the past three days grimaces in pain as he along with others waits along the border for permission to go to refugee camps near Palong Khali, Bangladesh, Thursday, Nov. 2 2017. More than 600,000 Rohingya from northern Rakhine state have fled to Bangladesh since Aug. 25, when Myanmar security forces began a scorched-earth campaign against Rohingya villages.: photo by Bernat Armangue/AP, 2 November 2017

Rohingya man Nur Ahmad, 70, his wife Lalu Bibi and their grand daughter Ashuka Bibi, 5, who crossed over to Bangladesh the previous day, wait for permission to go to the refugee camps after spending the night in the rice fields near Palong Khali, Bangladesh, Thursday, Nov. 2 2017. It took them 9 days to reach the border since they left their family home at Buthi Dawng district. They were waiting at the border for three days and finally crossed Wednesday late evening.: photo by Bernat Armangue/AP, 2 November 2017

A Rohingya family which fled persecution in Myanmar waits along the border for permission to go to refugee camps near Palong Khali, Bangladesh, Thursday, Nov. 2 2017. More than 600,000 Rohingya from northern Rakhine state have fled to Bangladesh since Aug. 25, when Myanmar security forces began a scorched-earth campaign against Rohingya villages.: photo by Bernat Armangue/AP, 2 November 2017

Rohingya Muslims who have fled persecution in Myanmar wait along the border for permission to go to refugee camps near Palong Khali, Bangladesh, Thursday, Nov. 2 2017. More than 600,000 Rohingya from northern Rakhine state have fled to Bangladesh since Aug. 25, when Myanmar security forces began a scorched-earth campaign against Rohingya villages.: photo by Bernat Armangue/AP, 1 November 2017

An exhausted Rohingya lies on the muddy ground after crossing over from the Myanmar border into Bangladesh, near Palong Khali, Bangladesh, Wednesday, Nov. 1 2017. In a scene that’s played out over and over again, at least 2,000 exhausted and starving Rohingya crossed the swollen Naf river on Wednesday and waited along the Bangladesh border for permission to cross, fleeing persecution in Myanmar.: photo by Bernat Armangue/AP, 1 November 2017

Rohingya Muslims help another after crossing the Naf river near Palong Khali, Bangladesh, Wednesday, Nov. 1 2017. In a scene that’s played out over and over again, at least 2,000 exhausted and starving Rohingya crossed the swollen Naf river on Wednesday and waited along the Bangladesh border for permission to cross, fleeing persecution in Myanmar.: photo by Bernat Armangue/AP, 1 November 2017

Rohingya women carry children and belongings and walk after having just crossed the Naf river near Palong Khali, Bangladesh, Wednesday, Nov. 1 2017. On Wednesday at least 2,000 exhausted and starving people waited in rice paddy fields at one border crossing for Bangladesh’s border guards to let them enter. It’s a scene that’s played out over and over again with heartbeaking regularity as hundreds of thousands of Rohingya Muslims have fled persecution in Myanmar and escaped to neighboring Bangladesh.: photo by Bernat Armangue/AP, 1 November 2017

Rohingya Muslims carry their young children and belongings after crossing the border from Myanmar into Bangladesh, near Palong Khali, Bangladesh, Wednesday, Nov. 1, 2017. In a scene that’s played out over and over again, at least 2,000 exhausted and starving Rohingya crossed the swollen Naf river on Wednesday and waited along the Bangladesh border for permission to cross, fleeing persecution in Myanmar.: photo by Bernat Armangue/AP, 1 November 2017

Groups of Rohingya Muslims cross the Naf river at the border between Myanmar and Bangladesh, near Palong Khali, Bangladesh, Wednesday, Nov. 1 2017. On Wednesday at least 2,000 exhausted and starving Rohingya crossed the swollen Naf river and waited along the border for permission to cross. It’s a scene that’s played out over and over again with heartbeaking regularity as hundreds of thousands of Rohingya Muslims have fled persecution in Myanmar and escaped to neighboring Bangladesh.: photo by Bernat Armangue/AP, 1 November 2017

A Rohingya child sleeps inside a basket in which he was carried as a group of Rohingya fled Myanmar into Bangladesh, near Palong Khali, Bangladesh, Wednesday, Nov. 1, 2017. In a scene that’s played out over and over again, at least 2,000 exhausted and starving Rohingya crossed the swollen Naf river on Wednesday and waited along the Bangladesh border for permission to cross, fleeing persecution in Myanmar.: photo by Bernat Armangue/AP, 1 November 2017

A week ago, #Myanmar, journo @AungNaingSoeAns was detained w/ 2 other reporters and a driver. Nobody has been able to see him, incl lawyer.: image via Poppy McPherson @poppymcp, 2 November 2017

A week ago, #Myanmar, journo @AungNaingSoeAns was detained w/ 2 other reporters and a driver. Nobody has been able to see him, incl lawyer.: image via Poppy McPherson @poppymcp, 2 November 2017

Tears roll down the cheeks of a child while drinking water from a kettle, as Rohingya Muslims who have fled persecution in Myanmar wait along the border for permission to move further towards refugee camps near Palong Khali, Bangladesh, Thursday, Nov. 2, 2017. More than 600,000 Rohingya from northern Rakhine state have fled to Bangladesh since Aug. 25, when Myanmar security forces began a scorched-earth campaign against Rohingya villages.: photo by Bernat Armangue/AP, 2 November 2017

The violence, which the U.N. describes as ethnic cleansing, has pushed more than 600,000 Rohingya into Bangladesh.

Rohingya Muslims who have fled persecution in Myanmar wait along the border for permission to move further towards refugee camps near Palong Khali, Bangladesh, Thursday, Nov. 2 2017. More than 600,000 Rohingya from northern Rakhine state have fled to Bangladesh since Aug. 25, when Myanmar security forces began a scorched-earth campaign against Rohingya villages.: photo by Bernat Armangue/AP, 2 November 2017

A Rohingya woman who has fled persecution in Myanmar is carried by others as they wait along the border for permission to move further towards refugee camps near Palong Khali, Bangladesh, Thursday, Nov. 2 2017. More than 600,000 Rohingya from northern Rakhine state have fled to Bangladesh since Aug. 25, when Myanmar security forces began a scorched-earth campaign against Rohingya villages.: photo by Bernat Armangue/AP, 2 November 201

A Rohingya woman who fled persecution in Myanmar tries to dry her land documents that got wet as she waits along the border for permission to move further towards refugee camps near Palong Khali, Bangladesh, Thursday, Nov. 2 2017. More than 600,000 Rohingya from northern Rakhine state have fled to Bangladesh since Aug. 25, when Myanmar security forces began a scorched-earth campaign against Rohingya villages.: photo by Bernat Armangue/AP, 2 November 2017

Rohingya Muslims who have fled persecution in Myanmar wait along the border for permission to move further towards refugee camps near Palong Khali, Bangladesh, Thursday, Nov. 2 2017. More than 600,000 Rohingya from northern Rakhine state have fled to Bangladesh since Aug. 25, when Myanmar security forces began a scorched-earth campaign against Rohingya villages.: photo by Bernat Armangue/AP, 2 November 2017

Rohingya Muslims who have fled persecution in Myanmar wait along the border for permission to move further towards refugee camps near Palong Khali, Bangladesh, Thursday, Nov. 2 2017. More than 600,000 Rohingya from northern Rakhine state have fled to Bangladesh since Aug. 25, when Myanmar security forces began a scorched-earth campaign against Rohingya villages.: photo by Bernat Armangue/AP, 2 November 2017

Rohingya Muslims await chance to enter Bangladesh: AP, 2 November 2017

Tears roll down the cheeks of a child while drinking water from a kettle, as Rohingya Muslims who have fled persecution in Myanmar wait along the border for permission to move further towards refugee camps near Palong Khali, Bangladesh, Thursday, Nov. 2, 2017. More than 600,000 Rohingya from northern Rakhine state have fled to Bangladesh since Aug. 25, when Myanmar security forces began a scorched-earth campaign against Rohingya villages.: photo by Bernat Armangue/AP, 2 November 2017

PALONG KHALI, Bangladesh (AP) — The scene has played out with

heartbreaking regularity as hundreds of thousands of Rohingya Muslims

have fled persecution in Myanmar into neighboring Bangladesh: terrified

knots of men, women and children crossing the swollen Naf River and

waiting along the border for permission to cross.

On Thursday, at least 2,000 exhausted and starving people waited in

rice paddy fields at one border crossing for Bangladesh border guards to

let them enter. They have been waiting for two days and while they were

given packets of food by aid groups, permission to enter eluded them.

So they waited, crouched in the muddy fields. The children carried

younger siblings. The elderly were helped along by relatives. Without

enough drinking water to go around, many people drank from the muddy

canals around the fields.

Most of the refugees had walked for as many as 10 days before they

were able to cross the river. Along the way, they said, they were robbed

multiple times by Myanmar soldiers of what little cash they had and

even belongings like plastic sheets.

All of them were hungry and exhausted. Some collapsed. Others wept as they clung to their children.

The exodus of Rohingya Muslims started Aug. 25 when insurgents attacked dozens of police posts in Myanmar.

The retribution from Myanmar’s authorities was swift and brutal.

Hundreds of Rohingya villages in Rakhine state have been set on fire.

Fleeing Rohingya have told stories of arson and rape and shootings by

Myanmar soldiers and Buddhist mobs.

The violence, which the U.N. describes as ethnic cleansing, has pushed more than 600,000 Rohingya into Bangladesh.

Rohingya Muslims who have fled persecution in Myanmar wait along the border for permission to move further towards refugee camps near Palong Khali, Bangladesh, Thursday, Nov. 2 2017. More than 600,000 Rohingya from northern Rakhine state have fled to Bangladesh since Aug. 25, when Myanmar security forces began a scorched-earth campaign against Rohingya villages.: photo by Bernat Armangue/AP, 2 November 2017

A Rohingya woman who has fled persecution in Myanmar is carried by others as they wait along the border for permission to move further towards refugee camps near Palong Khali, Bangladesh, Thursday, Nov. 2 2017. More than 600,000 Rohingya from northern Rakhine state have fled to Bangladesh since Aug. 25, when Myanmar security forces began a scorched-earth campaign against Rohingya villages.: photo by Bernat Armangue/AP, 2 November 201

A Rohingya woman who fled persecution in Myanmar tries to dry her land documents that got wet as she waits along the border for permission to move further towards refugee camps near Palong Khali, Bangladesh, Thursday, Nov. 2 2017. More than 600,000 Rohingya from northern Rakhine state have fled to Bangladesh since Aug. 25, when Myanmar security forces began a scorched-earth campaign against Rohingya villages.: photo by Bernat Armangue/AP, 2 November 2017

Rohingya Muslims who have fled persecution in Myanmar wait along the border for permission to move further towards refugee camps near Palong Khali, Bangladesh, Thursday, Nov. 2 2017. More than 600,000 Rohingya from northern Rakhine state have fled to Bangladesh since Aug. 25, when Myanmar security forces began a scorched-earth campaign against Rohingya villages.: photo by Bernat Armangue/AP, 2 November 2017

Rohingya Muslims who have fled persecution in Myanmar wait along the border for permission to move further towards refugee camps near Palong Khali, Bangladesh, Thursday, Nov. 2 2017. More than 600,000 Rohingya from northern Rakhine state have fled to Bangladesh since Aug. 25, when Myanmar security forces began a scorched-earth campaign against Rohingya villages.: photo by Bernat Armangue/AP, 2 November 2017

Two children sleep as Rohingya Muslims who have fled persecution in Myanmar wait along the border for permission to move further towards refugee camps near Palong Khali, Bangladesh, Thursday, Nov. 2 2017. More than 600,000 Rohingya from northern Rakhine state have fled to Bangladesh since Aug. 25, when Myanmar security forces began a scorched-earth campaign against Rohingya villages.: photo by Bernat Armangue/AP, 2 November 2017

Rohingya man Muhammed Yunus, 28, who did not have any food for the past three days grimaces in pain as he along with others waits along the border for permission to go to refugee camps near Palong Khali, Bangladesh, Thursday, Nov. 2 2017. More than 600,000 Rohingya from northern Rakhine state have fled to Bangladesh since Aug. 25, when Myanmar security forces began a scorched-earth campaign against Rohingya villages.: photo by Bernat Armangue/AP, 2 November 2017

A Rohingya woman who fled persecution in Myanmar tries to dry her land documents that got wet as she waits along the border for permission to move further towards refugee camps near Palong Khali, Bangladesh, Thursday, Nov. 2 2017. More than 600,000 Rohingya from northern Rakhine state have fled to Bangladesh since Aug. 25, when Myanmar security forces began a scorched-earth campaign against Rohingya villages.: photo by Bernat Armangue/AP, 2 November 2017

Rohingya woman Mahmuda Khatun, who fled persecution in Myanmar holds her newborn baby, as she along with others waits along the border for permission to go ahead towards refugee camps near Palong Khali, Bangladesh, Thursday, Nov. 2 2017. Khatun took 10 days to reach the border and the baby was born 5 days ago. The group crossed the border yesterday evening. More than 600,000 Rohingya from northern Rakhine state have fled to Bangladesh since Aug. 25, when Myanmar security forces began a scorched-earth campaign against Rohingya villages.: photo by Bernat Armangue/AP, 2 November 2017

Rohingya man Muhammed Yunus, 28, who did not have any food for the past three days grimaces in pain as he along with others waits along the border for permission to go to refugee camps near Palong Khali, Bangladesh, Thursday, Nov. 2 2017. More than 600,000 Rohingya from northern Rakhine state have fled to Bangladesh since Aug. 25, when Myanmar security forces began a scorched-earth campaign against Rohingya villages.: photo by Bernat Armangue/AP, 2 November 2017

Rohingya man Nur Ahmad, 70, his wife Lalu Bibi and their grand daughter Ashuka Bibi, 5, who crossed over to Bangladesh the previous day, wait for permission to go to the refugee camps after spending the night in the rice fields near Palong Khali, Bangladesh, Thursday, Nov. 2 2017. It took them 9 days to reach the border since they left their family home at Buthi Dawng district. They were waiting at the border for three days and finally crossed Wednesday late evening.: photo by Bernat Armangue/AP, 2 November 2017

A Rohingya family which fled persecution in Myanmar waits along the border for permission to go to refugee camps near Palong Khali, Bangladesh, Thursday, Nov. 2 2017. More than 600,000 Rohingya from northern Rakhine state have fled to Bangladesh since Aug. 25, when Myanmar security forces began a scorched-earth campaign against Rohingya villages.: photo by Bernat Armangue/AP, 2 November 2017

Rohingya Muslims who have fled persecution in Myanmar wait along the border for permission to go to refugee camps near Palong Khali, Bangladesh, Thursday, Nov. 2 2017. More than 600,000 Rohingya from northern Rakhine state have fled to Bangladesh since Aug. 25, when Myanmar security forces began a scorched-earth campaign against Rohingya villages.: photo by Bernat Armangue/AP, 1 November 2017

An exhausted Rohingya lies on the muddy ground after crossing over from the Myanmar border into Bangladesh, near Palong Khali, Bangladesh, Wednesday, Nov. 1 2017. In a scene that’s played out over and over again, at least 2,000 exhausted and starving Rohingya crossed the swollen Naf river on Wednesday and waited along the Bangladesh border for permission to cross, fleeing persecution in Myanmar.: photo by Bernat Armangue/AP, 1 November 2017

Rohingya Muslims help another after crossing the Naf river near Palong Khali, Bangladesh, Wednesday, Nov. 1 2017. In a scene that’s played out over and over again, at least 2,000 exhausted and starving Rohingya crossed the swollen Naf river on Wednesday and waited along the Bangladesh border for permission to cross, fleeing persecution in Myanmar.: photo by Bernat Armangue/AP, 1 November 2017

Rohingya women carry children and belongings and walk after having just crossed the Naf river near Palong Khali, Bangladesh, Wednesday, Nov. 1 2017. On Wednesday at least 2,000 exhausted and starving people waited in rice paddy fields at one border crossing for Bangladesh’s border guards to let them enter. It’s a scene that’s played out over and over again with heartbeaking regularity as hundreds of thousands of Rohingya Muslims have fled persecution in Myanmar and escaped to neighboring Bangladesh.: photo by Bernat Armangue/AP, 1 November 2017

Rohingya Muslims carry their young children and belongings after crossing the border from Myanmar into Bangladesh, near Palong Khali, Bangladesh, Wednesday, Nov. 1, 2017. In a scene that’s played out over and over again, at least 2,000 exhausted and starving Rohingya crossed the swollen Naf river on Wednesday and waited along the Bangladesh border for permission to cross, fleeing persecution in Myanmar.: photo by Bernat Armangue/AP, 1 November 2017

Groups of Rohingya Muslims cross the Naf river at the border between Myanmar and Bangladesh, near Palong Khali, Bangladesh, Wednesday, Nov. 1 2017. On Wednesday at least 2,000 exhausted and starving Rohingya crossed the swollen Naf river and waited along the border for permission to cross. It’s a scene that’s played out over and over again with heartbeaking regularity as hundreds of thousands of Rohingya Muslims have fled persecution in Myanmar and escaped to neighboring Bangladesh.: photo by Bernat Armangue/AP, 1 November 2017

A Rohingya child sleeps inside a basket in which he was carried as a group of Rohingya fled Myanmar into Bangladesh, near Palong Khali, Bangladesh, Wednesday, Nov. 1, 2017. In a scene that’s played out over and over again, at least 2,000 exhausted and starving Rohingya crossed the swollen Naf river on Wednesday and waited along the Bangladesh border for permission to cross, fleeing persecution in Myanmar.: photo by Bernat Armangue/AP, 1 November 2017

A week ago, #Myanmar, journo @AungNaingSoeAns was detained w/ 2 other reporters and a driver. Nobody has been able to see him, incl lawyer.: image via Poppy McPherson @poppymcp, 2 November 2017

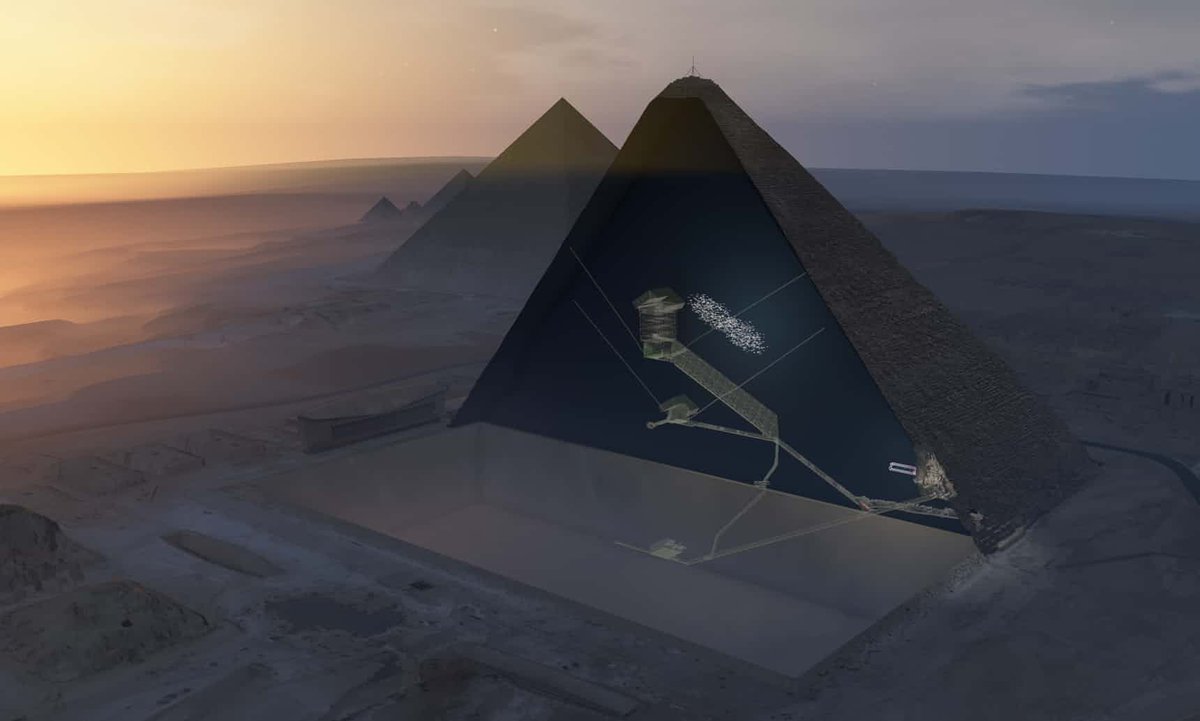

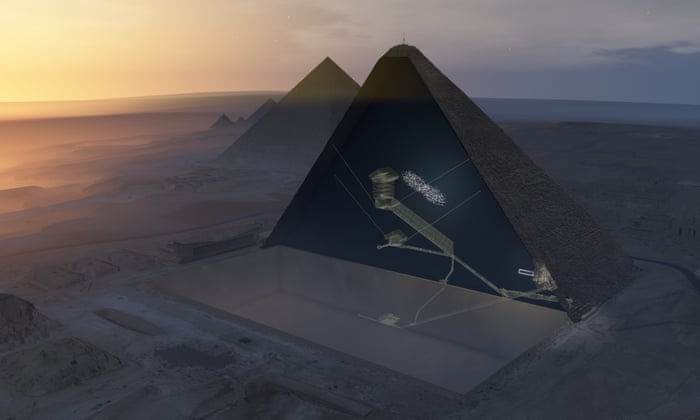

#Archeologists discover mysterious void deep within Great Pyramid of #Giza #Egypt: image via Ancient History @ahencyclopedia, 2 November 2017

A 3D aerial view of the Great Pyramid of Giza, showing the chambers within, as well as the newly-detected cavity.: photo by ScanPyramids mission, 2 November 2017

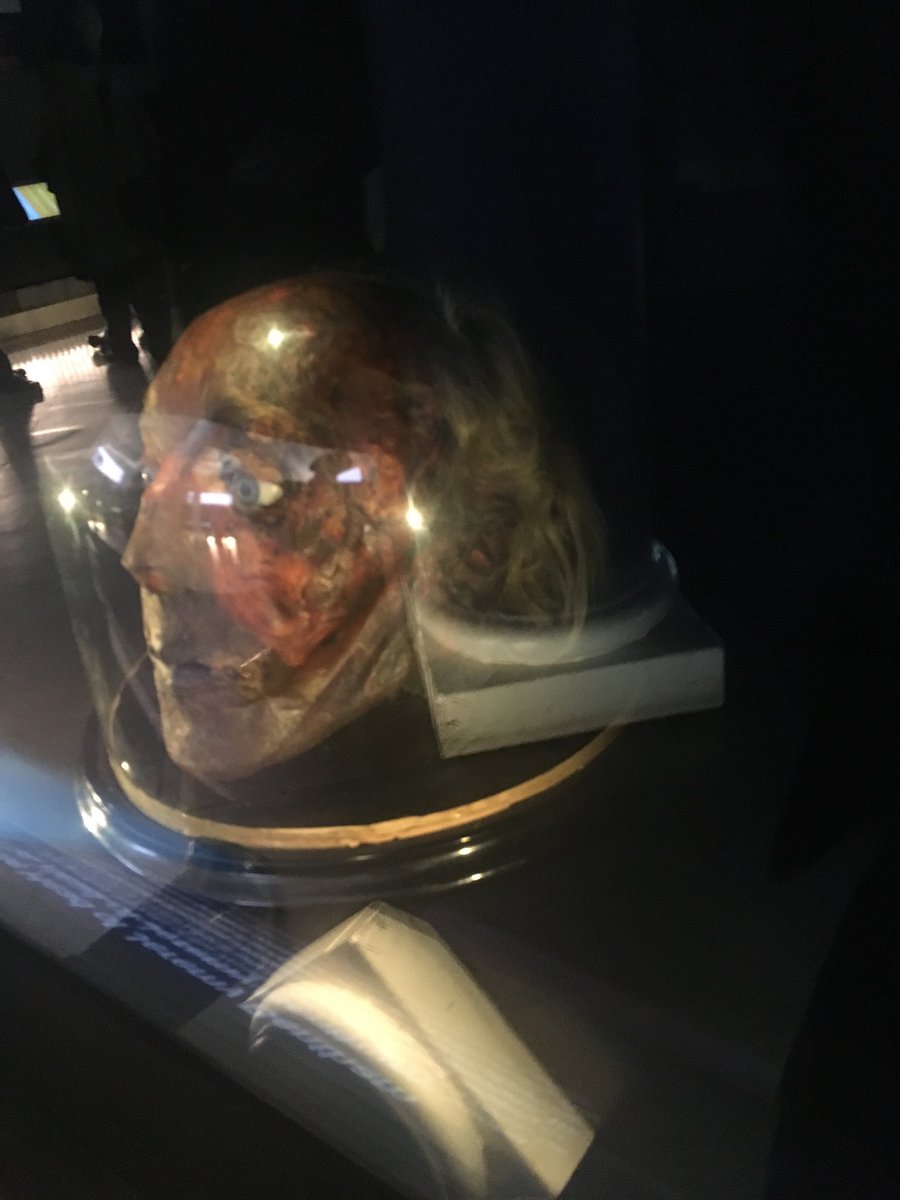

Don't miss the chance to see Bentham's head @UCLMuseums - unlike Egyptian Pharaohs, he wanted you to see him like this: image via Nigel Warburton @philosophy bites, 7 October 2017

A Rohingya Muslim man who has not eaten for the past three days grimaces in pain as he waits along the border in Bangladesh. @BernatArmangue: image via AP Images @AP_Images, 2 November 2017

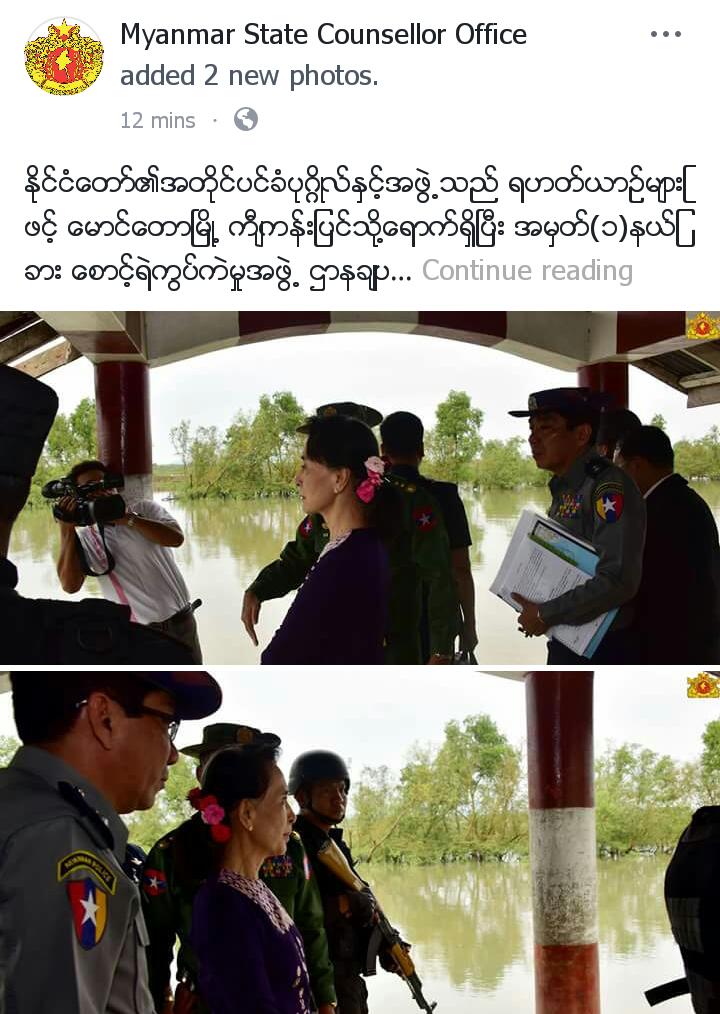

#Myanmar #AungSanSuuKyi on a rare day trip to #Maungdaw #Rakhine with ministers and key biz leaders meeting #ethnic citizens and #Rohingyas: image via May Wong @MayWongCNA, 2 November 2017

#Myanmar #AungSanSuuKyi praises #soldiers #police #security forces she met in #Rakhine for ensuring stability under difficult circumstances: image via May Wong @MayWongCNA, 2 November 2017

EPA pictures of #Myanmar state counsellor Aung San Suu Ky visiting #Rakhine state today.: image via Hnin Yadana Zaw @hninyadanazaw, 1 November 2017

EPA pictures of #Myanmar state counsellor Aung San Suu Ky visiting #Rakhine state today.: image via Hnin Yadana Zaw @hninyadanazaw, 1 November 2017

EPA pictures of #Myanmar state counsellor Aung San Suu Ky visiting #Rakhine state today.: image via Hnin Yadana Zaw @hninyadanazaw, 1 November 2017

EPA pictures of #Myanmar state counsellor Aung San Suu Ky visiting #Rakhine state today.: image via Hnin Yadana Zaw @hninyadanazaw, 1 November 2017

Leaving Afghanistan border, 2017: photo by Davide Albani, 22 August 2017

Leaving Afghanistan border, 2017: photo by Davide Albani, 22 August 2017

Leaving Afghanistan border, 2017: photo by Davide Albani, 22 August 2017

Uzbekistan, 2017: photo by Davide Albani, 15 August 2017

Uzbekistan, 2017: photo by Davide Albani, 15 August 2017

Uzbekistan, 2017: photo by Davide Albani, 15 August 2017

Uzbekistan, 2017: photo by Davide Albani, 3 October 2017

Uzbekistan, 2017: photo by Davide Albani, 3 October 2017

Uzbekistan, 2017: photo by Davide Albani, 3 October 2017

Uzbekistan, 2017: photo by Davide Albani, 20 August 2017

Uzbekistan, 2017: photo by Davide Albani, 20 August 2017

Uzbekistan, 2017: photo by Davide Albani, 20 August 2017

Rare protest in junta-ruled Thailand after mourning chaos: Panu Wongcha-um, Reuters, 1 November 2017

BANGKOK (Reuters) - Authorities in Thailand’s southeastern Chonburi province braced for more demonstrations on Wednesday after hundreds of furious residents gathered a day earlier in a rare protest to complain about bureaucratic incompetence.

Residents complained about long lines that lasted more than 12 hours and general disorganization surrounding activities to mark the funeral of late King Bhumibol Adulyadej who was cremated in Bangkok last week in a $90 million funeral.

The protest defied a junta ban on gatherings of more than five people that has been in place since a May 2014 coup.

It is also rare because anything remotely related to the monarchy is a sensitive topic in Thailand - the royals are protected by a draconian lese-majeste law, which criminalize all perceived insults toward the monarchy.

The Chonburi protests, however, were directed at the local authorities and not at the palace.

Protesters in the sea-side province shouted “Get out!” on Tuesday as they demanded that provincial governor Pakarathon Tienchai step down over what they said was poor organization of ceremonies to mark the funeral.

Many wore yellow, the king’s color.

There have been similar calls for the governor of Nonthaburi province, north of Bangkok, to step down. Some in Nonthaburi reported waiting for up to eight hours to lay flowers for the late king.

Chonburi Governor Pakarathon spoke to the crowd on Tuesday and denied his staff had mismanaged the event.

Prime Minister Prayuth Chan-ocha on Tuesday urged Thais to forgive those involved in the funeral organization and overlook any problems that arose.

“The number of people who took part in the funeral caused a few problems,” he said.

Preferential Treatment

Hundreds of thousands of people turned out to see King Bhumibol’s funeral in Bangkok last week.

The late king, who ruled for more than seven decades, was seen as a father-figure.

For those unable to make the trip to Bangkok, 85 miniature replicas of the cremation pyre were arranged across Thailand.

Hundreds of other areas were designated as places for mourners to lay flowers.

“I waited 13 hours!” shouted one Chonburi protestor on Tuesday.

Similar stories have emerged around the country as netizens took to social media to vent their anger.

Some said the mismanagement exposed Thailand’s jarring class divide.

Chonburi protesters said they were unhappy with the funeral’s $90 million budget.

The late king frequently spoke about self-sufficiency and was portrayed as a frugal man despite his own enormous wealth.

Others still argued that government officials were given preferential treatment when laying flowers.

“Officials went first before the public,” Tanarit Kumwivat, form the northern province of Chiang Mai, said in a Facebook post.

The Chonburi protest comes at the end of an epoch. King Bhumibol, who was also known as “the people’s king”, was a rare figure of unity in the politically divided nation and his death has left some Thais anxious about the future.

Confusion follows surprise decision not to air Thai royal Cremation: photo by Khaosod, 27 October 2017

Questions, Acceptance Follow Surprise Decision Not to Air Cremation: Sasiwan Mokkhasen, Khaosod English, 27 October 2017

BANGKOK — Upon hearing the news, Kiattichai Phongkaew suddenly collapsed on the ground. Crying, he turned to face the Sanam Luang, where smoke lingered in the air above the crematorium, and prostrated.

The cremation of King Bhumibol was already finished, and he had not known until a reporter mentioned it.

“I missed the last chance to send you off, dad,” he said, breaking into tears.

Like Kiattichai, thousands of mourners waited last night on

Ratchadamnoen Avenue to bid farewell to the king they called father.

They believed the actual cremation would be broadcast live as it had

been done in previous funerals for other royal family members.

But that broadcast never came, and no announcement would be made until much later.

In a scene similar to Oct. 13 last year, when well-wishers at Siriraj Hospital were the last to learn the king had died, devout mourners lashed by rain and seared by sun on

The decision not to broadcast the actual cremation seemed to even catch uniformed officials at the event, some of whom said it was merely delayed and still coming, while another simply said he did not know why it wasn’t shown.

By Friday, competing explanations were emerging as to why people were not allowed to witness the cremation of their longest-reigning monarch. But whether it was a last-minute change or just a poorly communicated decision, one fact not in dispute is that it came as a surprise – and disappointment – to the nation.

Mourners sleep early Friday morning on Ratchadamnoen Avenue where they had camped overnight in hope of witnessing King Bhumibol’s actual cremation.: photo by Khaosod, 27 October 2017

Those who slept on the sidewalk since Monday night and tolerated heavy downpours were able to secure places inside the ceremony area starting at 5am on Wednesday.

By Thursday morning, more than 110,000 mourners had filled the royal field, but there were even more people who failed to get access and decided to stay around including on Ratchadamnoen Avenue. They slept on mats and used their bags as pillows. Some were prepared with blankets.

The official televised broadcast schedule did not note the 10pm cremation. It only stated there would be a cremation ceremony at 4:30pm and the next scheduled content was at 8am for the collection of the king’s remains.

Torpong Soonthornvipas vowed to remain until morning with his 7-year-old daughter.: photo by Khaosod, 27 October 2017

But most people believed they would get to watch the actual cremation

because the practice has been done in other royal funerals.

“I don’t know what they all say, but the actual cremation has to happen per tradition,” said Torpong Soonthornvipas, who sat with his 7-year-old daughter and vowed to stay until morning. “It has always been showed every time in the past.”

Reporters were told the live broadcast would run all night, and that public performances marking the end of the mourning period would be suspended during the actual cremation. At 9pm, a Khaosod English reporter at the official press center was told the ceremony would definitely be televised.

As 10pm was approaching, more people arrived. Fifteen minutes before the scheduled cremation, police allowed more newcomers onto the avenue.

“We can’t get inside Sanam Luang but we will graab the king for the last time together here on the road,” shouted a policeman as he urged people to rush in.

At 10pm, people were still sitting quietly in front of the screen getting ready for a time they never wanted to come. Many meditated. But the screens kept looping a documentary about King Bhumibol’s works. At one point, it cut to show a live orchestra performing in the Sanam Luang.

When the time arrived, audience members watching from home saw the coverage cut and replaced with a message: “Royal Cremation of His Majesty King Bhumibol. Everyone is advised to turn toward the Meru Mas and pay their highest respects.”

Those on Ratchadamnoen Avenue saw nothing except the continuing performances and assumed the ritual was delayed.

A Khaosod English reporter at the press center confirmed at 10:38pm that the actual cremation would not be aired. At about 11pm, a royal fire was lit at the replica crematorium on Ratchadamnoen Avenue to burn sandalwood flowers. Next to it, a large screen was still broadcasting an orchestral performance.

By that time, the crowd was confused and reluctant to leave. No official announcement was made. Some decided to leave, while others refused and chose to stay.

Kanokwan Rattanaphoom, 25, broke into tears after hearing the cremation had happened.: photo by Khaosod, 27 October 2017

Despite looking visibly agitated, Kanokwan Rattanaphoom said she was

not disappointed. The 25-year-old broke into tears after hearing the

cremation had happened.

“I came from Satun province, arriving in Bangkok last night,” she said wiping tears away.

“I slept here in the road last night in the hope of seeing it.”

According to another Khaosod reporter, a palace media liaison informed some reporters at about 10pm, when the cremation was scheduled to begin, that it would not be televised because the king’s successor, His Majesty the King Rama X, had deigned it a “private affair.”

It was at 11:16pm that government spokesman Sansern Kaewkamnerd announced the broadcast and ceremony had ended and coverage would resume in the morning. He did not elaborate on why the actual cremation was not televised.

Ten minutes later, smoke emerged from the top of crematorium, and that was when more people were convinced, despite being so close to where it happened, they had already missed the time they had waited a lifetime to experience.

Smoke lingers in the air above the crematorium: photo by Khaosod, 27 October 2017

‘Mai Pen Rai’

“I missed the last chance to send you off, dad,” he said, breaking into tears.

Kiattichai Phongkaew: photo by Khaosod, 27 October 2017

But that broadcast never came, and no announcement would be made until much later.

In a scene similar to Oct. 13 last year, when well-wishers at Siriraj Hospital were the last to learn the king had died, devout mourners lashed by rain and seared by sun on

Ratchadamnoen Avenue had no idea

what was going on until they heard from friends watching from home.

The decision not to broadcast the actual cremation seemed to even catch uniformed officials at the event, some of whom said it was merely delayed and still coming, while another simply said he did not know why it wasn’t shown.

By Friday, competing explanations were emerging as to why people were not allowed to witness the cremation of their longest-reigning monarch. But whether it was a last-minute change or just a poorly communicated decision, one fact not in dispute is that it came as a surprise – and disappointment – to the nation.

Mourners sleep early Friday morning on Ratchadamnoen Avenue where they had camped overnight in hope of witnessing King Bhumibol’s actual cremation.: photo by Khaosod, 27 October 2017

Wanting to Be Close

By Thursday morning, more than 110,000 mourners had filled the royal field, but there were even more people who failed to get access and decided to stay around including on Ratchadamnoen Avenue. They slept on mats and used their bags as pillows. Some were prepared with blankets.

The official televised broadcast schedule did not note the 10pm cremation. It only stated there would be a cremation ceremony at 4:30pm and the next scheduled content was at 8am for the collection of the king’s remains.

Torpong Soonthornvipas vowed to remain until morning with his 7-year-old daughter.: photo by Khaosod, 27 October 2017

“I don’t know what they all say, but the actual cremation has to happen per tradition,” said Torpong Soonthornvipas, who sat with his 7-year-old daughter and vowed to stay until morning. “It has always been showed every time in the past.”

Reporters were told the live broadcast would run all night, and that public performances marking the end of the mourning period would be suspended during the actual cremation. At 9pm, a Khaosod English reporter at the official press center was told the ceremony would definitely be televised.

Black-clad

mourners sit quietly in front of giant screen Thursday night on

Ratchadamnoen Avenue awaiting the actual cremation to be televised.: photo by Khaosod, 27 October 2017

As 10pm was approaching, more people arrived. Fifteen minutes before the scheduled cremation, police allowed more newcomers onto the avenue.

“We can’t get inside Sanam Luang but we will graab the king for the last time together here on the road,” shouted a policeman as he urged people to rush in.

At 10pm, people were still sitting quietly in front of the screen getting ready for a time they never wanted to come. Many meditated. But the screens kept looping a documentary about King Bhumibol’s works. At one point, it cut to show a live orchestra performing in the Sanam Luang.

When the time arrived, audience members watching from home saw the coverage cut and replaced with a message: “Royal Cremation of His Majesty King Bhumibol. Everyone is advised to turn toward the Meru Mas and pay their highest respects.”

Those on Ratchadamnoen Avenue saw nothing except the continuing performances and assumed the ritual was delayed.

A Khaosod English reporter at the press center confirmed at 10:38pm that the actual cremation would not be aired. At about 11pm, a royal fire was lit at the replica crematorium on Ratchadamnoen Avenue to burn sandalwood flowers. Next to it, a large screen was still broadcasting an orchestral performance.

By that time, the crowd was confused and reluctant to leave. No official announcement was made. Some decided to leave, while others refused and chose to stay.

Kanokwan Rattanaphoom, 25, broke into tears after hearing the cremation had happened.: photo by Khaosod, 27 October 2017

“I came from Satun province, arriving in Bangkok last night,” she said wiping tears away.

“I slept here in the road last night in the hope of seeing it.”

According to another Khaosod reporter, a palace media liaison informed some reporters at about 10pm, when the cremation was scheduled to begin, that it would not be televised because the king’s successor, His Majesty the King Rama X, had deigned it a “private affair.”

It was at 11:16pm that government spokesman Sansern Kaewkamnerd announced the broadcast and ceremony had ended and coverage would resume in the morning. He did not elaborate on why the actual cremation was not televised.

Ten minutes later, smoke emerged from the top of crematorium, and that was when more people were convinced, despite being so close to where it happened, they had already missed the time they had waited a lifetime to experience.

Smoke lingers in the air above the crematorium: photo by Khaosod, 27 October 2017

Online, some speculated that it might have been for sake of privacy of the king’s wife, Queen Sirikit, who has been ailing and out of the public eye for several years.

Asked why they thought the cremation was done in secret, mourners on the street had different opinions. Most went along with common-sense rationales.

“It’s a private ceremony and should be exclusive for royal family members,” Kiettisak said. “They tried to appear to be strong for the whole day, now we need to give them some private time.”

Mourners sleep on Ratchadamnoen Avenue early Friday morning.: photo by Khaosod, 27 October 2017

Thai Buddhist traditions regard actual cremation as an exclusive ritual for family members and close friends. Guests are only allowed to attend the symbolic cremation. However, recent royal funerals including those of King Bhumibol’s mother and sister allowed the public to witness by televised video.

“They probably didn’t want mass grieving to happen,” another man said. “It would have been difficult for people to cope if they had seen it.”

The confusion wasn’t limited to Ratchadamnoen Road but was felt nationwide. On the country’s most popular webboard Pantip, many users raised the question of why it was skipped. The common response was the same.

“Don’t expect it based on our familiarity,” wrote member No. 786797 in the top comment. “We revere King Rama IX as father of the nation, somebody regards him as their own father. But in reality, he is only the father of the four royal highnesses. … Even the actual cremations of commoners are done exclusively for their families.”

Some even suggested that expectations to be able to watch it were inappropriate.

“They are very headstrong. I feel sorry for dad,” another comment said.

Mourners in the streets awaiting the royal cremation ceremony broadcast that would never happen.: photo by Khaosod, 27 October 2017

Mourners in the streets awaiting the royal cremation ceremony broadcast that would never happen.: photo by Khaosod, 27 October 2017

Mourners in the streets awaiting the royal cremation ceremony broadcast that would never happen.: photo by Khaosod, 27 October 2017

Mourners in the streets awaiting the royal cremation ceremony broadcast that would never happen.: photo by Khaosod, 27 October 2017

Mourners in the streets awaiting the royal cremation ceremony broadcast that would never happen.: photo by Khaosod, 27 October 2017

No Details About 42 Fugitives Arrested at Royal Funeral: Teeranai Charuvastra, Khaosod English, 31 October 2017

Police officers stand guard close to Meru Mas crematorium complex on Friday morning: photo by Khaosod, 31 October 2017

King Bhumibol leaving a Buddhist temple in Bangkok after being ordained a monk for two weeks in 1956.: photo by Associated Press

King Bhumibol leaving a Buddhist temple in Bangkok after being ordained a monk for two weeks in 1956.: photo by Associated Press

How a Thai King Made Wealth Seem Sacred: Matthew Phillips, The New York Times, 24 October 2017

ABERYSTWYTH, Wales — Bhumibol Adulyadej, Thailand’s previous king, will be cremated on Oct. 26 on a grassy patch of land in front of the Grand Palace in central Bangkok. He died a year ago, after a 70-year reign, and he is credited with transforming Thailand into a modern nation-state and unifying the country during times of political turmoil.

An army of royal artists and artisans has built for the occasion an elaborate set of structures that, in Thai Hindu-Buddhist cosmology, symbolizes the mountains,

continents and oceans at the edge of the universe. The funeral pyre,

precisely 50.49 meters tall, represents Mount Meru, which is thought to

connect the human realm to the divine.

A select 7,500 have been invited to the palace grounds for the five-day ceremony, but more than 250,000 mourners are expected to gather in surrounding areas. The government is reported to have spent between $30 million and $90 million on the preparations. Eighty-five replicas of the site in Bangkok have been erected across the country, as well as nearly 100 memorials throughout the world.

The cost, the crowds, the exquisite re-enactment of ancient spectacle — all of it may seem fit for a king, but the scale of the pomp signals a remarkable evolution. Although the main rituals of a Thai royal cremation have barely changed since the 14th century, the pageantry surrounding them has, reflecting the political concerns of each period. Over the last century or so, the Thai monarchy has gone from seemingly frugal to unabashedly rich — and it has managed that by casting King Bhumibol as a Buddha-like figure.

During

the 19th century, the integration of Siam, as Thailand was known then,

into the world economy consolidated the royal family’s power and wealth.

But that also made the monarchy vulnerable to charges of despotism and

wastefulness, precisely at a time when the public was becoming more

outspoken, emboldened in part by the ferment of revolution in other

countries. For centuries before that, commoners had been encouraged to

celebrate a Siamese king’s ascent to the heavens with theater, fireworks

and other public events. Yet the cremation ceremony proper was held

away from the eye of the people.

By the turn of the 20th century, especially after the abolition of slavery in Siam in 1905, even royal ceremonials adapted to shifting norms about state accountability. The cremation of King Chulalongkorn, also known as Rama V, in 1911, was the first to reflect such concerns. Partly in keeping with royal funerals in Europe — the place perceived then as the vanguard of modernity — no celebratory events were held, but the general public was allowed to attend the cremation itself. Yet it would be a modest affair, according to the instructions King Chulalongkorn had left: He asked that his funeral pyre be reduced from 80 meters — the height of the structure used for Rama IV’s cremation in 1868 — to 33 meters.

The cremation pyre of Rama VI in 1926 was smaller still: Even though an attempt to overthrow the monarchy in 1912 had failed, complaints about its extravagance had grown louder. After the revolution of 1932 transformed Siam from an absolute monarchy to a constitutional one, the cost of official ceremonials naturally remained a sensitive political issue.

Then in 1946, Bhumibol ascended to the throne, and after a discreet first decade, largely out of the limelight, his reign gained momentum. A military coup in 1958, pro-American and high on Thai pride, placed the (U.S.-born) king at its center, and the Thai public reacted enthusiastically.

Today, six decades later, there is little discussion over the expense of King Bhumibol’s cremation. Twelve million Thais are said to have visited his body as it lay in state over the last year. The funeral pyre of King Bhumibol, or Rama IX, is the largest since that of Rama IV.

Sculptures and scaffolding at the site for King Bhumibol Adulyadej’s cremation this week in Bangkok. The government is reported to have spent between $30 million and $90 million on preparations for the five-day ceremony.: photo by Athit Perawongmetha/Reuters, 24 October 2017

Sculptures and scaffolding at the site for King Bhumibol Adulyadej’s cremation this week in Bangkok. The government is reported to have spent between $30 million and $90 million on preparations for the five-day ceremony.: photo by Athit Perawongmetha/Reuters, 24 October 2017

King

Bhumibol is often credited with foiling a Communist movement during the

Cold War, liberalizing the Thai economy and keeping the country

together despite its often-fractious politics. But another of his great

successes, at least for the monarchy, has been to make royal wealth seem

sacred, and any contribution to it appear virtuous.

In a country afflicted by economic inequality and widespread corruption, King Bhumibol was portrayed as benevolent and frugal, detached from the material world and concerned first and foremost by the well-being of his subjects. (A squeezed-out tube of his toothpaste was exhibited to the public, set on a golden cloth, after his death, as evidence of his fabled economy.) By appearing to embody the virtues of a great Buddhist ruler — “love-kindness,” charity and perseverance, as the sacred texts go — King Bhumibol acquired the aura of his boddhisvatta.

King Bhumibol’s very status as a Buddha-in-the-making also helped transform the Thai monarchy from a beleaguered institution, struggling for political and financial survival, at the start of his reign into a thriving corporate operation today.

The royal family, thanks in part to a raft of projects with business, academia, the arts and charities, has implanted itself at the center of Thailand’s cultural and social life — apparently far from the messy, brutal realities of capitalism and political gamesmanship.

Giving money or labor to a royally endorsed project has come to be seen as a good deed, and so an opportunity to improve one’s chances of an auspicious rebirth in the Buddhist reincarnation cycle.

Donations to the royal household since King Bhumibol’s death have totaled more than $26 million. Tens of thousands of Thais have volunteered to support the cremation ceremony, providing accommodation, transportation and security, as well as cleaning services. According to the government’s public relations department, volunteers under 17 will be given a piggy bank inscribed with this statement by the late king, “The power of people who think positively, do good deeds and are grateful is the power that will bring about peace and prosperity to families, communities and the country.”

King Bhumibol’s material legacy also is great. The Crown Property Bureau, the agency that manages the royal finances, has vastly expanded its business portfolio. Neither the bureau’s assets nor its operations are entirely known, but the Thai monarchy is now thought to be the world’s richest, with an estimated fortune of at least $30 billion. Under King Bhumibol, the royal family of Thailand has become fabulously rich by cultivating an appearance of frugality and making wealth seem immaterial — or rather, divine.

Matthew Phillips is a historian of modern Thailand at Aberystwyth University, Wales.

The procession ended when the symbolic funerary urn was placed in the crematorium at Sanam Luang, the ceremonial grounds outside the palace compound in Bangkok. King Bhumibol’s body, in a separate coffin, was to be cremated late Thursday.: photo by Wason Wanichakorn/Associated Press, 26 October 2017

The procession ended when the symbolic funerary urn was placed in the crematorium at Sanam Luang, the ceremonial grounds outside the palace compound in Bangkok. King Bhumibol’s body, in a separate coffin, was to be cremated late Thursday.: photo by Wason Wanichakorn/Associated Press, 26 October 2017

The ceremony started with a volley of artillery fire.: photo by Rungroj Yongrit/European Pressphoto Agency, 26 October 2017

The ceremony started with a volley of artillery fire.: photo by Rungroj Yongrit/European Pressphoto Agency, 26 October 2017

Mourners, hoping for a view of the procession, gathered early Thursday morning.: photo by Adam Dean for The New York Times, 26 October 2017

Mourners, hoping for a view of the procession, gathered early Thursday morning.: photo by Adam Dean for The New York Times, 26 October 2017

Thais from across the country descended on the capital to catch a glimpse of the procession.: photo by Anthony Wallace/Agence France-Presse / Getty Images, 26 October 2017

Thais from across the country descended on the capital to catch a glimpse of the procession.: photo by Anthony Wallace/Agence France-Presse / Getty Images, 26 October 2017

Though the king did not live at the Grand Palace, the Bangkok complex is the symbolic and spiritual home of the monarchy. The funeral pyre was built nearby at the parade grounds called Sanam Luang.: photo by Anthony Wallace/Agence France-Presse / Getty Images, 26 October 2017

Though the king did not live

at the Grand Palace, the Bangkok complex is the symbolic and spiritual

home of the monarchy. The funeral pyre was built nearby at the parade

grounds called Sanam Luang.: photo by Anthony Wallace/Agence France-Presse / Getty Images, 26 October 2017

Monocle. Bangkok, Thailand.: photo by Job Jetichwan Chowadee, 1 June 2017

Monocle. Bangkok, Thailand.: photo by Job Jetichwan Chowadee, 1 June 2017

Monocle. Bangkok, Thailand.: photo by Job Jetichwan Chowadee, 1 June 2017

#23 KhaoYai, Nakornrajasema, Thailand: photo by Add Wimolrungkarat, 5 January 2017

#23 KhaoYai, Nakornrajasema, Thailand: photo by Add Wimolrungkarat, 5 January 2017

#23 KhaoYai, Nakornrajasema, Thailand: photo by Add Wimolrungkarat, 5 January 2017

Black-capped Kingfisher (Halcyon pileata), Phra Non, Nakhon Sawan, Thailand: photo by J.J. Harrison, 2 February 2011

_DSC3235 [Chumphon, Thailand]: photo by noppadol maitreechit, 7 November 2016

_DSC3235 [Chumphon, Thailand]: photo by noppadol maitreechit, 7 November 2016

_DSC3235 [Chumphon, Thailand]: photo by noppadol maitreechit, 7 November 2016

Whip. Bangkok, Thailand.: photo by Job Jetwichan Chaowadee, 14 August 2017

Whip. Bangkok, Thailand.: photo by Job Jetwichan Chaowadee, 14 August 2017

Whip. Bangkok, Thailand.: photo by Job Jetwichan Chaowadee, 14 August 2017

[Songkhla, Hat Yai, Thailand]: photo by Sakulchai Sikitikul, 6 August 2017

[Songkhla, Hat Yai, Thailand]: photo by Sakulchai Sikitikul, 6 August 2017

[Songkhla, Hat Yai, Thailand]: photo by Sakulchai Sikitikul, 6 August 2017

[untitled]: photo by Setsiri Silapasuwanchai, 7 January 2017

P6240810: photo by Krongpon Komutkul, 24 June 2017

P6240810: photo by Krongpon Komutkul, 24 June 2017

P6240810: photo by Krongpon Komutkul, 24 June 2017

Bangkok, Thailand 2017: photo by Bopit Intaraswat, 3 May 2560

Bangkok, Thailand 2017: photo by Bopit Intaraswat, 3 May 2560

Bangkok, Thailand 2017: photo by Bopit Intaraswat, 3 May 2560

_DSF4584: photo by Chanwut BC Kul, 26 March 2017

_DSF4584: photo by Chanwut BC Kul, 26 March 2017

_DSF4584: photo by Chanwut BC Kul, 26 March 2017

Bangkok, Thailand 2016: photo by Bopit Intaraswat, 20 October 2016

Bangkok, Thailand 2016: photo by Bopit Intaraswat, 20 October 2016

Bangkok, Thailand 2016: photo by Bopit Intaraswat, 20 October 2016

Bangkok, Thailand 2016: photo by Bopit Intaraswat, 21 December 2016

Bangkok, Thailand 2016: photo by Bopit Intaraswat, 21 December 2016

Bangkok, Thailand 2016: photo by Bopit Intaraswat, 21 December 2016

#13: photo by THANASORN JANEKANJIT, 20 August 2017

#13: photo by THANASORN JANEKANJIT, 20 August 2017

#13: photo by THANASORN JANEKANJIT, 20 August 2017

_DSF 3732: photo by Chanwut BC Kul, 29 March 2017

_DSF 3732: photo by Chanwut BC Kul, 29 March 2017

_DSF 3732: photo by Chanwut BC Kul, 29 March 2017

Lightning strikes behind the aircraft carrier USS John C. Stennis (CVN 74) as she steams through the gulf of Thailand: photo by Mass Communication Specialist 3rd Class Jon Husman, 9 April 2009 (U.S. Navy)

A man pays to buy new iPhone Xs from those who just bought them in Hong Kong: image via Reuters Pictures @reuterspictures, 3 November 2017

@Apple

CEO @tim_cook greeted customers purchasing the new #iPhoneX at an

#Apple store in Palo Alto. The iPhone X went on sale today for $1K: image via Justin Sullivan @sullyfoto, 3 November 2017

@Apple

CEO @tim_cook greeted customers purchasing the new #iPhoneX at an

#Apple store in Palo Alto. The iPhone X went on sale today for $1K: image via Justin Sullivan @sullyfoto, 3 November 2017

@Apple

CEO @tim_cook greeted customers purchasing the new #iPhoneX at an

#Apple store in Palo Alto. The iPhone X went on sale today for $1K: image via Justin Sullivan @sullyfoto, 3 November 2017

@Apple CEO @tim_cook greeted customers purchasing the new #iPhoneX at an #Apple store in Palo Alto. The iPhone X went on sale today for $1K: image via Justin Sullivan @sullyfoto, 3 November 2017

#04: photo by Krongpon Komutkul, 23 April 2017

#04: photo by Krongpon Komutkul, 23 April 2017

#04: photo by Krongpon Komutkul, 23 April 2017

#Mexico Great portraits during Catrina competition in Morelia in #Mexico by #AFP @omarjose1985 #DiaDeMuertos #Catrina #Catrinas: image via Sylvain Estibal @Sestibal, 1 November 2017

#Mexico Great portraits during Catrina competition in Morelia in #Mexico by #AFP @omarjose1985 #DiaDeMuertos #Catrina #Catrinas: image via Sylvain Estibal @Sestibal, 1 November 2017

#Mexico Great portraits during Catrina competition in Morelia in #Mexico by #AFP @omarjose1985 #DiaDeMuertos #Catrina #Catrinas: image via Sylvain Estibal @Sestibal, 1 November 2017

#Mexico Great portraits during Catrina competition in Morelia in #Mexico by #AFP @omarjose1985 #DiaDeMuertos #Catrina #Catrinas: image via Sylvain Estibal @Sestibal, 1 November 2017

Male woolly mammoths were risk takers and died in ‘silly ways’ more often than females #FossilFriday: image via The Ice Age @Jamie_Woodward, 3 November 2017

young guns [Phuket. Thailand]: photo by polod, 8 October 2016

young guns [Phuket. Thailand]: photo by polod, 8 October 2016

young guns [Phuket. Thailand]: photo by polod, 8 October 2016

No comments:

Post a Comment