.

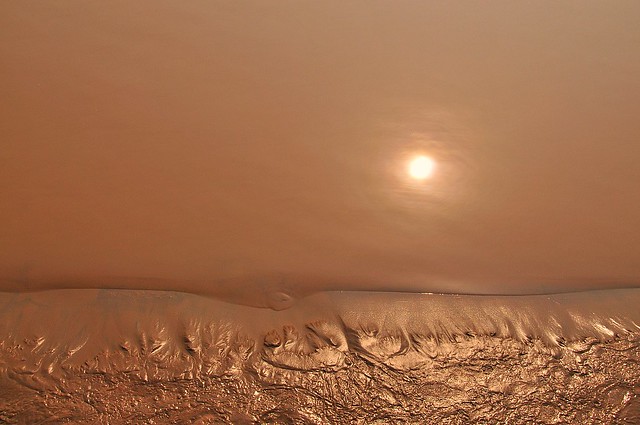

The first turn of the Yangtze, at Shigu, Yunnan Province: photo by Jialiang Gao, 2003

Now he has seen the girl Hsiang-Hsiang,

..Now back to the guerrilla band;

And she goes with him down the vale

..And pauses at the strand.

The mud is yellow, deep, and thick,

..And their feet stick, where the stream turns.

'Make me two models out of this,

..That clutches as it yearns.

'Make one of me and one of you,

..And both shall be alive.

Were there no magic in the dolls

..The children could not thrive.

'When you have made them smash them back:

..They yet shall live again.

Again make dolls of you and me

..But mix them grain by grain.

'So your flesh shall be part of mine

..And part of mine be yours.

Brother and sister we shall be

..Whose unity endures.

'Always the sister doll will cry,

..Made in these careful ways,

Cry on and on, Come back to me,

..Come back, in a few days.'

[after the Chinese of Li Chi]

Tang dynasty figurines: photo by Sailko, 27 November 2011

Yellow River, Jinan, China: photo by Azalea Lover, 3 February 2009

Yellow River Gorge, Jianza, Quinghai, China: photo by Cåsbr (Xuan Che), 25 August 2007

Yellow River, Jianza, Quinghai, China: photo by Cåsbr (Xuan Che), 25 August 2007

Yellow River, Jianza, Quinghai, China:: photo by Cåsbr (Xuan Che), 25 August 2007

William Empson (1906-1984): Chinese Ballad, 1951, from Selected Poems (enlarged edition), 1962. This poem of the Tang dynasty poet Li Chi (Li Qi, 690-751) was "translated'' by Empson in 1951 while

he was in China, and includes a speaker who, according to Empson's note, is "fighting

the Japanese".

___

Empson admired what he called "the singing line",

especially if it also had some clarity of thought. One of his most

beautiful poems is "Chinese Ballad", based on a poem by Li Chi: "It's

not by me at all, you see, but I always feel it clears the palate after a

reading of my stuff." [Empson's note.] [Christopher] Ricks called the poem "Empson's nunc dimittis as a

poet", an assurance that "though life may be essentially inadequate to

the human spirit, the human spirit is essentially adequate to life." The

parting lovers entrust their faith to two dolls, made of mud; the dolls

will be smashed and reconstituted, "grain by grain",

'So your flesh shall be part of mine

..And part of mine be yours.

Brother and sister we shall be

..Whose unity endures.

..And part of mine be yours.

Brother and sister we shall be

..Whose unity endures.

'Always the sister doll will cry,

..Made in these careful ways,

Cry on and on, Come back to me,

..Come back, in a few days.'

..Made in these careful ways,

Cry on and on, Come back to me,

..Come back, in a few days.'

The

conceit is worthy of Donne, Empson's own chosen master, and the tone is

genuinely ballad-like (as Donne's sometimes was). It is an allegory of

the pain of a parting that seems perpetual, of a resistance (supported

by art, by the making and mixing of the dolls) to the dreadful sense of

the contradictions involved in living and thinking about it, that seems

to underlie much of Empson's work, as indeed it does that of his admired

Milton. The radical contradiction is between the hope of human

happiness, for which, at least at certain moments, we feel ourselves so

wonderfully suited, and the power of the world as it inescapably is to

frustrate or even ridicule that feeling. Hence Empson's endorsement of

the Buddhist position that "no sort of temporal life whatever can

satisfy the human spirit." Yet Buddhism also takes account of the fact

that "birth as a human being is an opportunity of inestimable value. He

who is so born has at least a chance of hearing the truth and acquiring

merit."

-- Frank Kermode, in William Empson: A Most Noteworthy Poet, 2000

6 comments:

And too, see:

William Empson: Aubade

William Empson: Ignorance of Death

William Empson: Let It Go

Tom,

Thanks for this, a beautiful Sunday morning offering --

So your flesh shall be part of mine,

And part of mind be yours.

And the 'broken' ('faltering') rhythm of the last line, how it conveys all the feeling in the poem.

And those pictures of those mountains and rivers. . .

12.9

light coming into sky above still black

ridge, fingernail moon through branches

in foreground, sound of wave in channel

being that lets the present,

such that this is not

frame picture, work of said,

landscape and figures

whiteness of moon in cloudless blue sky,

tree-lined green of ridge above channel

And thank you for your discriminating eye and ear, Steve.

That "broken-back" line, the oldest kind of line in English poetry -- always makes me think of Wyatt, and how that rocking-horse see-saw rhythm induces a simplicity and directness of feeling.

There's a tenderness here that isn't always there in Empson.

When you have made them smash them back.

It's a child's game - playing seriously, making and unmaking. That "see-saw rhythm" is just right.

Perhaps it's the "hard" side of Empson that makes the more tender side credible, for me.

A bit about his time in the Far East, from The Poetry Archive (UK):

"Seven Types of Ambiguity made Empson's name and he was nominated for a fellowship at Magdalene College (Cambridge). However, when contraceptives were discovered in Empson's rooms the ensuing scandal meant the fellowship was rescinded and Empson was plunged into financial hardship. This crisis, though painful, was also the catalyst for a period of stimulating travel in the Far East which was to exert a powerful influence on his imagination. First Empson took up a teaching post in Japan followed, in 1937, by an invitation to teach at the University of Peking. However, when he arrived Empson found the staff on the brink of leaving in the face of the Japanese invasion. Empson fled with them and lived a peripatetic existence for two years teaching English poetry entirely from memory. Empson loved China, despite the hardships, and became very knowledgeable about Buddhism which he respected (as opposed to Christianity which he found morally repugnant and criticised openly). Despite these upheavals, Empson found time to publish his second groundbreaking book of criticism Some Versions of the Pastoral in 1935. The majority of his poetry was also written during the 20s and 30s. He returned to England at the outbreak of the Second World War and was employed by the BBC making broadcasts to the Far East. Empson married Hetta Crouse in 1941 and the couple had two sons. After the war Empson returned to Peking University for a further five years where he witnessed the rise of communism, leaving in 1952 when teaching conditions became more restricted."

lovely poem...wonderful pics!

Post a Comment