.

The Dream of St Ursula, from The Legend of St Ursula: Vittore Carpaccio (1472-1526), 1495, tempera on canvas, 274 x 267 cm (Gallerie dell'Accademia, Venice)

In the year 1869, just before leaving Venice I had been

carefully looking at a picture by Victor Carpaccio, representing the

dream of a young princess.

Carpaccio has taken much pain to explain to us, as far as he can, the kind of life she leads, by completely painting her little bedroom in the light of dawn, so that you can see everything in it. It is lighted by two doubly-arched windows, the arches being painted crimson round their edges, and the capitals of the shafts that bear them, gilded. They are filled at the top with small round panes of glass; but beneath, are open to the blue morning sky, with a low lattice across them; and in the one at the back of the room are set two beautiful white Greek vases with a plant in each; one having rich dark and pointed green leaves, the other crimson flowers, but not of any species known to me, each at the end of a branch like a spray of heath.

These flower-pots stand on a shelf which runs all round the room, and beneath the window, at about the height of the elbow, and serves to put things on anywhere: beneath it, down to the floor, the walls are covered with green cloth; but above are bare and white. The second window is nearly opposite the bed, and in front of it is the princess’s reading-table, some two feet and a half square, covered by a red cloth with a white border and dainty fringe; and beside it her seat, not at all like a reading chair in Oxford, but a very small three-legged stool like a music stool, covered with crimson cloth. On the table are a book, set up at a slope fittest for reading, and an hour-glass. Under the shelf near the table so as to be easily reached by the outstretched arm, is a press full of books. The door of this has been left open, and the books, I am grieved to say, are rather in disorder, having been pulled about before the princess went to bed, and one left standing on its side.

Opposite this window, on the white wall, is a small shrine or picture (I can’t see which, for it is in sharp retiring perspective), with a lamp before it, and a silver vessel hung from the lamp, looking like one for holding incense.

The bed is a broad four-poster, the posts being beautifully wrought golden or gilded rods, variously wreathed and branched, carrying a canopy of warm red. The princess’s shield is at the head of it, and the feet are raised entirely above the floor of the room, on a dais which projects at the lower end so as to form a seat, on which the child has laid her crown. Her little blue slippers lie at the side of the bed, — her white dog beside them, the coverlid is scarlet, the white sheet folded half way back over it; the young girl lies straight, bending neither at waist nor knee, the sheet rising and falling over her in a narrow unbroken wave, like the shape of the coverlid of the last sleep, when the turf scarcely rises. She is some seventeen or eighteen years old, her head is turned towards us on the pillow, the cheek resting on her hand, as if she were thinking, yet utterly calm in sleep, and almost colourless. Her hair is tied with a narrow riband, and divided into two wreaths, which encircle her head like a double crown. The white nightgown hides the arm raised on the pillow, down to the wrist.

At the door of the room an angel enters (the little dog, though lying awake, vigilant, takes no notice). He is a very small angel, his head just rises a little above the shelf round the room, and would only reach as high as the princess’s chin, if she were standing up. He has soft grey wings, lustreless; and his dress, of subdued blue, has violet sleeves, open above the elbow, and showing white sleeves below. He comes in without haste, his body, like a mortal one, casting shadow from the light through the door behind, his face perfectly quiet; a palm-branch in his right hand — a scroll in his left.

So dreams the princess, with blessed eyes, that need no earthly dawn. It is very pretty of Carpaccio to make her dream out the angel’s dress so particularly, and notice the slashed sleeves; and to dream so little an angel — very nearly a doll angel, — bringing her the branch of palm, and message. But the lovely characteristic of all is the evident delight of her continual life. Royal power over herself, and happiness in her flowers, her books, her sleeping and waking, her prayers, her dreams, her earth, her heaven….

“How do I know the princess is industrious?”

Partly by the trim state of her room, — by the hour-glass on the table, — by the evident use of all the books she has (well bound, every one of them, in stoutest leather or velvet, and with no dog’s-ears), more distinctly from another picture of her, not asleep. In that one a prince of England has sent to ask her in marriage: and her father, little liking to part with her, sends for her to his room to ask her what she would do. He sits, moody and sorrowful; she, standing before him in a plain house-wifely dress, talks quietly, going on with her needlework all the time.

A work-woman, friends, she, no less than a princess; and princess most in being so. In like manner, is a picture by a Florentine, whose mind I would fain have you know somewhat, as well as Carpaccio’s — Sandro Botticelli — the girl who is to be the wife of Moses, when he first sees her at the desert well, has fruit in her left hand, but a distaff in her right.

“To do good work, whether you live or die,” it is the entrance to all Princedoms; and if not done, the day will come, and that infallibly, when you must labour for evil instead of good.

John Ruskin: On Carpaccio's Dream of Saint Ursula, from Fors Clavigera (Sunnyside, Orpington, Kent, 1872)

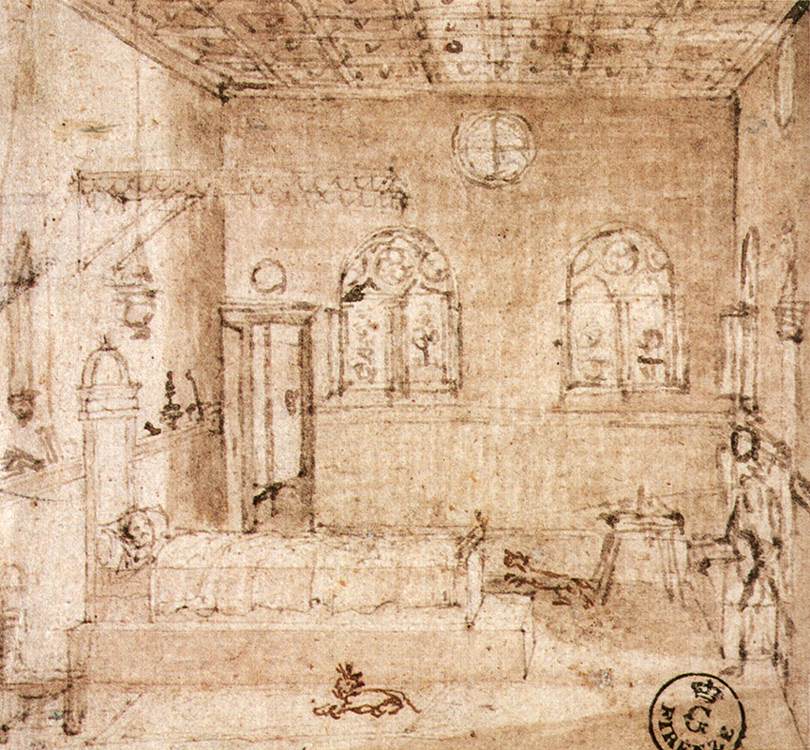

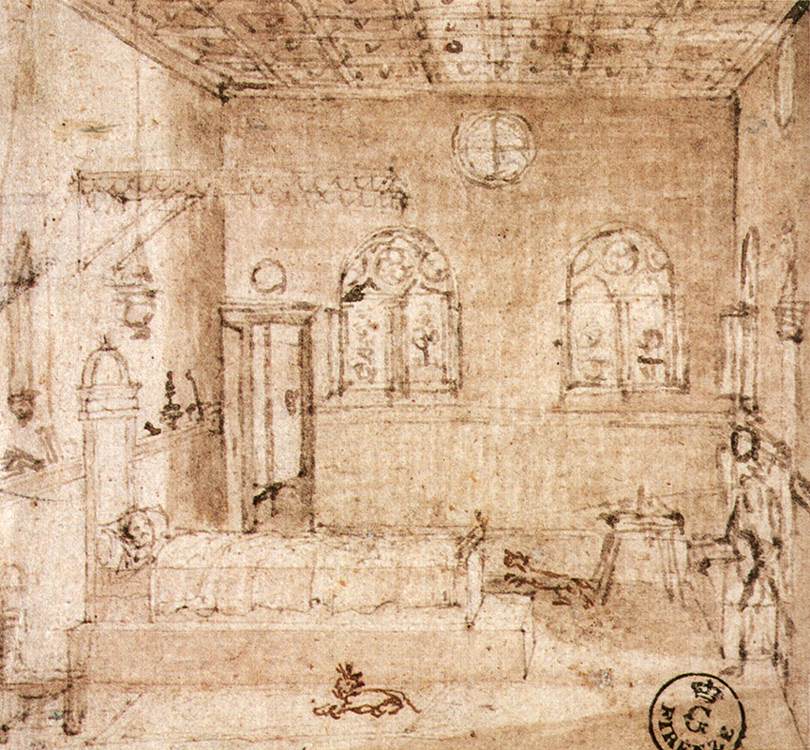

The Dream of St Ursula: Vittore Carpaccio, 1495, drawing (Galleria degli Uffizi, Florence)

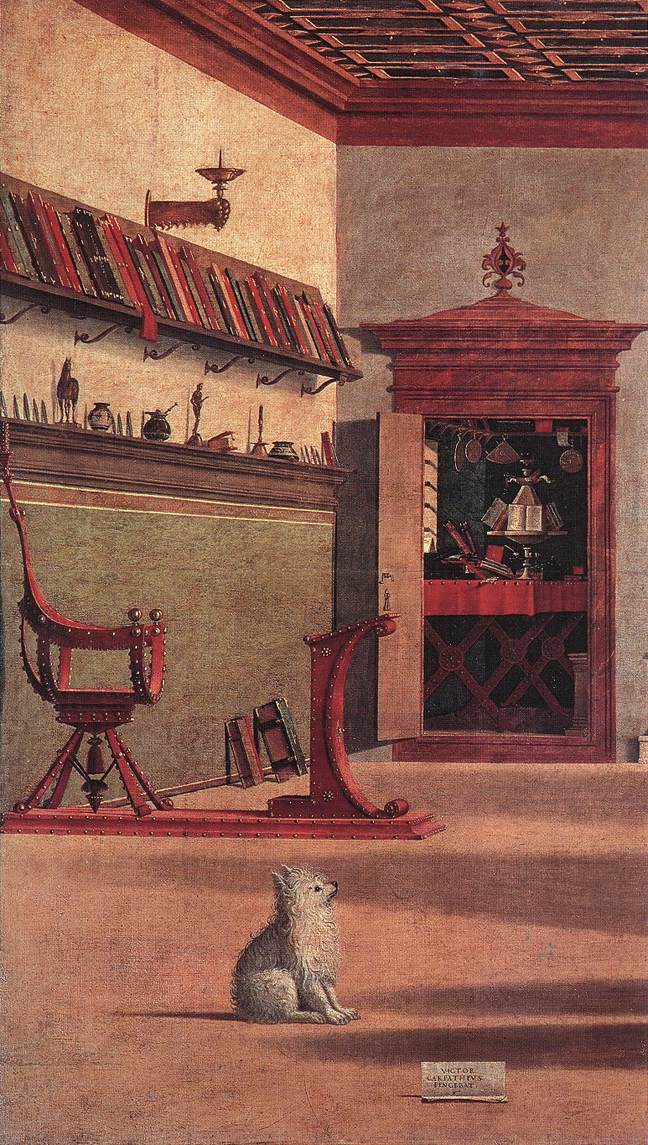

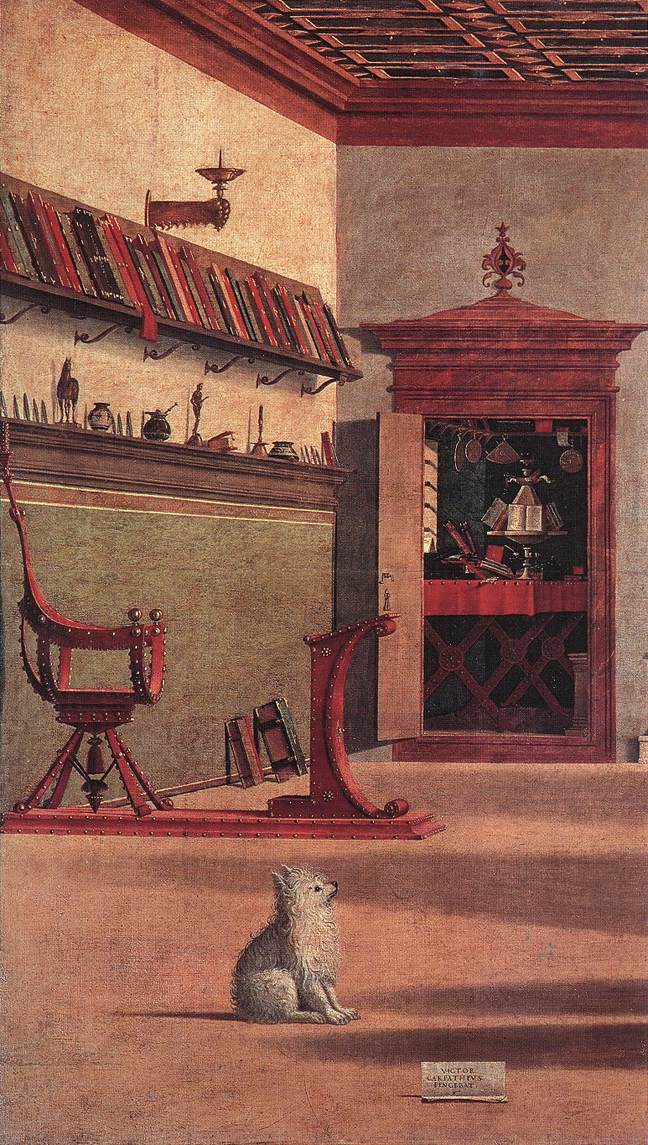

Vision of St Augustin (detail): Vittore Carpaccio, 1502, tempera on canvas (Scuola di San Giorgio degli Schiavoni, Venice)

Carpaccio has taken much pain to explain to us, as far as he can, the kind of life she leads, by completely painting her little bedroom in the light of dawn, so that you can see everything in it. It is lighted by two doubly-arched windows, the arches being painted crimson round their edges, and the capitals of the shafts that bear them, gilded. They are filled at the top with small round panes of glass; but beneath, are open to the blue morning sky, with a low lattice across them; and in the one at the back of the room are set two beautiful white Greek vases with a plant in each; one having rich dark and pointed green leaves, the other crimson flowers, but not of any species known to me, each at the end of a branch like a spray of heath.

These flower-pots stand on a shelf which runs all round the room, and beneath the window, at about the height of the elbow, and serves to put things on anywhere: beneath it, down to the floor, the walls are covered with green cloth; but above are bare and white. The second window is nearly opposite the bed, and in front of it is the princess’s reading-table, some two feet and a half square, covered by a red cloth with a white border and dainty fringe; and beside it her seat, not at all like a reading chair in Oxford, but a very small three-legged stool like a music stool, covered with crimson cloth. On the table are a book, set up at a slope fittest for reading, and an hour-glass. Under the shelf near the table so as to be easily reached by the outstretched arm, is a press full of books. The door of this has been left open, and the books, I am grieved to say, are rather in disorder, having been pulled about before the princess went to bed, and one left standing on its side.

Opposite this window, on the white wall, is a small shrine or picture (I can’t see which, for it is in sharp retiring perspective), with a lamp before it, and a silver vessel hung from the lamp, looking like one for holding incense.

The bed is a broad four-poster, the posts being beautifully wrought golden or gilded rods, variously wreathed and branched, carrying a canopy of warm red. The princess’s shield is at the head of it, and the feet are raised entirely above the floor of the room, on a dais which projects at the lower end so as to form a seat, on which the child has laid her crown. Her little blue slippers lie at the side of the bed, — her white dog beside them, the coverlid is scarlet, the white sheet folded half way back over it; the young girl lies straight, bending neither at waist nor knee, the sheet rising and falling over her in a narrow unbroken wave, like the shape of the coverlid of the last sleep, when the turf scarcely rises. She is some seventeen or eighteen years old, her head is turned towards us on the pillow, the cheek resting on her hand, as if she were thinking, yet utterly calm in sleep, and almost colourless. Her hair is tied with a narrow riband, and divided into two wreaths, which encircle her head like a double crown. The white nightgown hides the arm raised on the pillow, down to the wrist.

At the door of the room an angel enters (the little dog, though lying awake, vigilant, takes no notice). He is a very small angel, his head just rises a little above the shelf round the room, and would only reach as high as the princess’s chin, if she were standing up. He has soft grey wings, lustreless; and his dress, of subdued blue, has violet sleeves, open above the elbow, and showing white sleeves below. He comes in without haste, his body, like a mortal one, casting shadow from the light through the door behind, his face perfectly quiet; a palm-branch in his right hand — a scroll in his left.

So dreams the princess, with blessed eyes, that need no earthly dawn. It is very pretty of Carpaccio to make her dream out the angel’s dress so particularly, and notice the slashed sleeves; and to dream so little an angel — very nearly a doll angel, — bringing her the branch of palm, and message. But the lovely characteristic of all is the evident delight of her continual life. Royal power over herself, and happiness in her flowers, her books, her sleeping and waking, her prayers, her dreams, her earth, her heaven….

“How do I know the princess is industrious?”

Partly by the trim state of her room, — by the hour-glass on the table, — by the evident use of all the books she has (well bound, every one of them, in stoutest leather or velvet, and with no dog’s-ears), more distinctly from another picture of her, not asleep. In that one a prince of England has sent to ask her in marriage: and her father, little liking to part with her, sends for her to his room to ask her what she would do. He sits, moody and sorrowful; she, standing before him in a plain house-wifely dress, talks quietly, going on with her needlework all the time.

A work-woman, friends, she, no less than a princess; and princess most in being so. In like manner, is a picture by a Florentine, whose mind I would fain have you know somewhat, as well as Carpaccio’s — Sandro Botticelli — the girl who is to be the wife of Moses, when he first sees her at the desert well, has fruit in her left hand, but a distaff in her right.

“To do good work, whether you live or die,” it is the entrance to all Princedoms; and if not done, the day will come, and that infallibly, when you must labour for evil instead of good.

John Ruskin: On Carpaccio's Dream of Saint Ursula, from Fors Clavigera (Sunnyside, Orpington, Kent, 1872)

The Dream of St Ursula: Vittore Carpaccio, 1495, drawing (Galleria degli Uffizi, Florence)

Apotheosis of St Ursula (detail), from The Legend of St Ursula: Vittore Carpaccio, 1491, tempera on canvas (Gallerie dell'Accademia, Venice)

Arrival of the English Ambassadors (detail), from The Legend of St Ursula:: Vittore Carpaccio, 1495-1500, tempera on canvas (Gallerie dell'Accademia, Venice)

Arrival of the English Ambassadors (detail), from The Legend of St Ursula:: Vittore Carpaccio, 1495-1500, tempera on canvas (Gallerie dell'Accademia, Venice)

The Ambassadors Return to the English Court, from The Legend of St Ursula:: Vittore Carpaccio, 1495-1500, oil on canvas, 297 x 527 cm (Gallerie dell'Accademia, Venice)

Portrait of a Young Woman: Vittore Carpaccio, n.d., panel (Private collection)

Presentation of Jesus in the Temple (detail): Vittore Carpaccio, 1510, tempera on panel (Gallerie dell'Accademia, Venice)

St Stephen is Consecrated Deacon (detail): Vittore Carpaccio, n.d., tempera on canvas (Staatlche Museen, Berlin)

Vision of St Augustin: Vittore Carpaccio, 1502, tempera on canvas, 141 x 210 cm (Scuola di San Giorgio degli Schiavoni, Venice)

Vision of St Augustin (detail): Vittore Carpaccio, 1502, tempera on canvas (Scuola di San Giorgio degli Schiavoni, Venice)

The Healing of the Madman (detail): Vittore Carpaccio, c. 1496, tempera on canvas (Gallerie dell'Accademia, Venice)

The Healing of the Madman (detail): Vittore Carpaccio, c. 1496, tempera on canvas (Gallerie dell'Accademia, Venice)

The Lion of St Mark (detail): Vittore Carpaccio, 1516, tempera on canvas (Palazzo Ducale, Venice)

6 comments:

Little is known of the life of the Venetian painter Vittore Carpaccio. The most ambitious of his works are two great cycles of paintings, the Scenes from the Life of St Ursula (of which the most original is the top picture here, The Dream of St Ursula), and a subsequent cycle, Scenes from the Lives of St George and St Jerome (which includes the painting of St Augustin in his study, seen here). After these two major commissioned series, Carpaccio's fortunes went into decline, the anecdotal and "orientalizing" aspects of his work coming to be regarded as out-of-date. Today however his work is acknowledged, along with that of Gentile Bellini (who was probably a strong influence) as the two great Venetian masters. The beginning of this restoration of Carpaccio's critical reputation came with the enthusiastic assessment of the influential English critic John Ruskin (1819-1900).

The Ruskin essay on Carpaccio's masterpiece is one of a series of pamphlets addressed to "the workmen and labourers of Great Britain", composed between 1871 and 1884, and dedicated to affecting social and moral change -- a part of Ruskin's larger engagement with the betterment of the lives and conditions of the working classes.

The full set of 96 pamphlets in the Fors Clavigera series, originally published singly, were issued in an eight volume "popular edition" in 1886.

That edition, broken into four parts, can be found online here.

To a correspondent who had enquired about the pamphlet on the Carpaccio painting, Ruskin wrote:

"High up, in an out-of-the-way corner of the Academy in Venice, seen by no man -- nor woman neither -- of all the pictures in Europe the one I should choose for a gift, if a fairy gave me choice -- Victor Carpaccio's 'Vision of St. Ursula'"...

nice...interesting last words

Ursula's "...cheek resting on her hand..." is a very tender thing. The room's a perfect space for dreaming in.

"To do good work whether you live or die, " it is the entrance to all princedoms.

This is a clear statement against alienated labour. That this delicate man could play such a part in the labour movement in Britain gives me hope.

There's an unbroken line from John Ruskin to Raymond Williams. A history worth holding to.

That Ruskin to Williams line is a beautiful tracery of human care. I had thought the thread had been lost in the weeds until it turned up again, glimmering there in the dark, under a seat on the wooden bus.

This has not been an easy winter here, but a week of nights spent with Carpaccio and Ruskin came as sweet relief. It seems the best things open up to us most clearly when we most need them, perhaps perhaps.

Hi Tom - just back from Venice - and the unspeakable privilege and pleasure of eyeing up-close these masterpieces

love always

to you & A

as ever

Simon

http://serendipity250.blogspot.com/

The more I looked at this painting the more interesting it became, so much so that it inspired me to name my latest novel after it, The Dream of Saint Ursula, published by Black Rose Writers. The story is set in the Virgin Islands which Columbus named for Saint Ursula and her virgins. I would love to know if Columbus ever met Carpoccio. In any case, put the two together and its clear that the story of Saint Ursula must have been popular and powerful in that time period.

Post a Comment