.

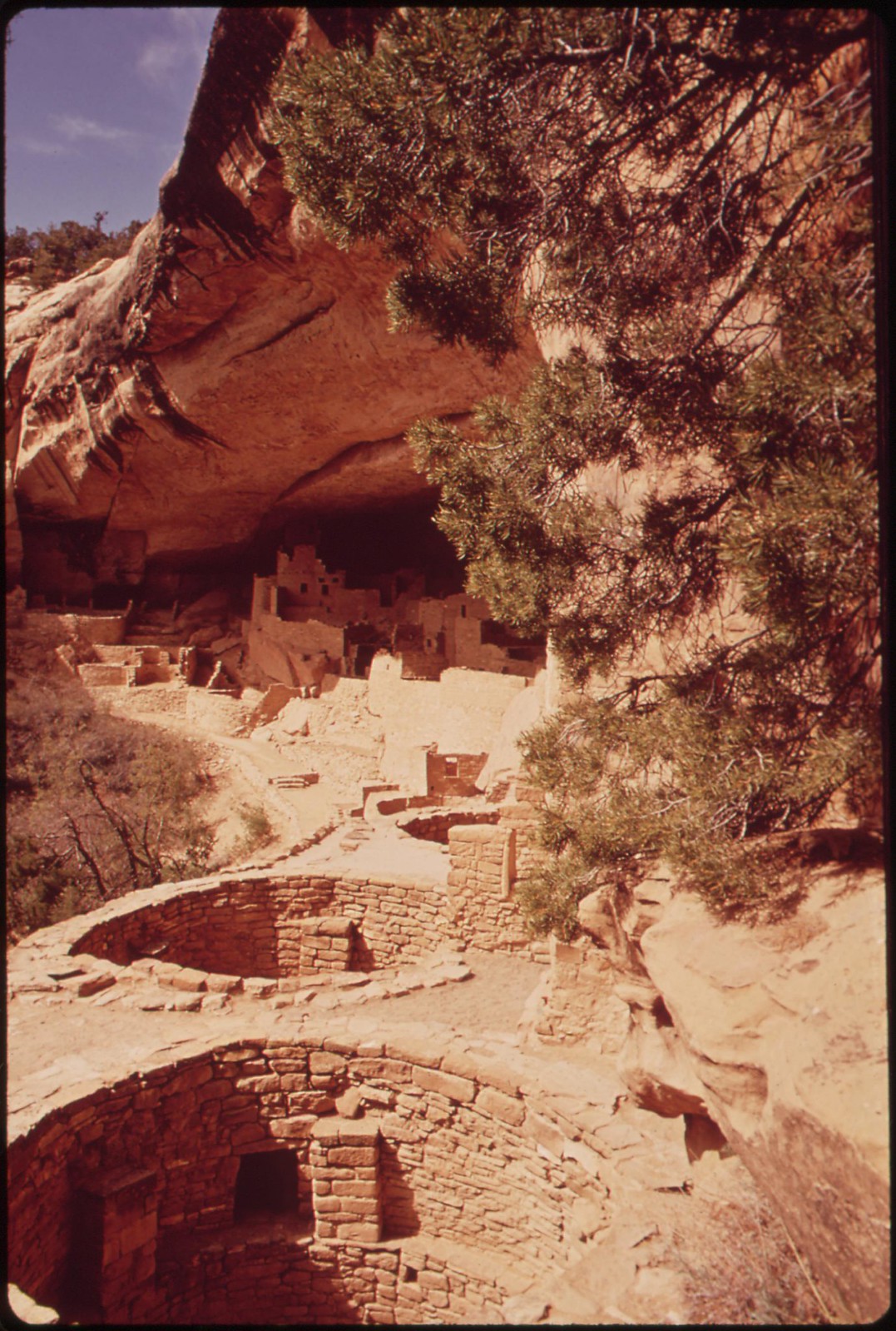

Cliff Palace was once a village of over 200 people and 23 kivas (ceremonial spaces), Mesa Verde, Montezuma County, Colorado

Up there in their eyrie

where the winds swirl

eagles afloat on thermals

the people knew what the face of nature

is there to conceal

beneath the infinite horizon

Very much here when they were here

when gone very

much gone

Part of Cliff Palace, an ancient Indian village built between 1100 and 1300 A.D., Mesa Verde, Montezuma County, Colorado

Cliff Palace is the largest remaining village of the pre-Columbian Indians. They lived in the Mesa Verde area until drought drove them out at the end of the 13th century

Eroded sandstone, part of Indian ruins dating from 1100 to 1300 A.D., Hovenweep National Monument, Colorado

Shiprock in smog, seen from Mesa Verde, Montezuma County, Colorado

Four-storey-high square tower house, built about 800 years ago, Mesa Verde, Montezuma County, Colorado

Photos by Boyd Norton for the Environmental Protection Agency's Documerica project, May 1972 (US National Archives)

19 comments:

This seems to have been about as as close as complex organic life got to the Aether in those yawning chasms of time before there was the aethernet.

For "very much here when they were here" one might perhaps read-in, much as on a motel room sign in some unexpectedly backward quarter, appropriate words of one's choosing, such as e.g. "no smartphone no WiFi", "no ATM no free internet", & c.

Life then, for people like this, was hard beyond our imagining.

Your life expectancy was probably about 25 on average.

If you got out of childhood, you might live to be 36, but you'd be one of the "ancient ones" with no teeth, crumbling joints, and white hair. We'd call that prematurely aging, except that that wasn't premature then. It was right on schedule.

What you ate: Anything that crawled or grew out of the ground that didn't make you puke when you ate it.

If you were a girl, you got fucked beginning at about age 11. You could very well die in childbirth. A woman might have six pregnancies by age 20.

Do the ruins that remain suggest they had a good life with a lively culture and a deep understanding of existence and the universe? Not really.

But the ruins are very picturesque in the Southwest light.

I've visited Mesa Verde. It's an astonishing place, full of mystery.

have they really gone?

Genetically, all North and Central and South American Indians derive from the Mongolians who crossed the Bering Straits, based on genetic markers. When this exactly happened is not known, but genetics don't lie.

All the ancient American cultures flourished, and then died. Anaszi, Aztec, Navajo, Mayan, Toltec, Inca. Mostly as a result of environmental exhaustion.

The lesson is clear. Over-exploit your region and it will eventually dry up. All the technological solutions in the world can't save a population if it explodes.

Northern Native American cultures seem to have reached a kind of stasis with respect to technological advancement, never getting beyond the tribal/nomadic stage.

These are generalizations. When you drill down into the details, Amer-Indian societies exhibit a lot more variety than the popular images of them do.

Maureen's comment, like a pebble dropped in still water, creates small ripples... of reflection.

Otherwise, an interesting exchange.

Well, Colin, for whatever good it may do, I, for one, having come to know you by way of this however limited medium, do give a fuck. But of course I don't have to tell you that this is a society built not on collective and communal values, which would include giving a fuck for specific individuals as well as for the community -- of course, in reality, the two motives would have had to come down to the same thing, as the interdependence between individuals in the collective was the basis of the social matrix.

To say these people had hard lives, when those lives are measured up against the lives people have now, is doubtless true, if you are accustomed to the institutional amenities that make life easier for those who have the means. But not everybody has the means -- ay, there's the rub. And those who do, by and large, don't give a fuck about those who don't. "I've got mine!"

And what is involved anyway in having the means? Is it possible to have a wallet bulging with plastic cards, to walk at night past shop doorways containing the bodies of people who do not have the means, and give a fuck? Would a person of means ever get out of the car to have a look? To offer help? To buy someone who's hungry a meal? When the internationally famous restaurant in our town had a small fire, more tax-paid fire department and police personnel were on hand than might have been needed at the scene of a small war. When someone is run over by a car in the street, though, who gives a fuck? Does the big chief of the village care? No way, he's out clapping sweaty palms with the developers. Institutionalized dehumanization tends to be invisible to those who are contained within the socioeconomic system as constituted.

I see this system as a game, much like vast, cruel playground game going on at a "special school" for the children of privilege. The players know the rules, and observe them. Others, fenced out of the schoolyard, cannot, or do not, wish to play.

Is it really possible to step away from the game?

A bit of the standard boilerplate data on the Mesa Verde cliff dwelling peoples (largely from NPS sources) -- perhaps a bit idealised, but still. (No mention of those terrible hardships, the lack of a Starbucks or an Andronico's, of parking and cable access and "routine medical testing" and all those other good things which make an artificially constructed system seem like a "natural", inevitable, necessary thing to its spellbound subjects. Still -- the clean air, the local economy in which all who are able participate...):

"The Cliff Palace is the largest cliff dwelling in North America. The structure was built by the Ancient Pueblo Peoples.

"Tree ring dating indicates that construction and refurbishing of Cliff Palace was continuous from c. 1190 CE through c. 1260 CE, although the major portion of the building was done within a twenty-year time span. The Ancestral Pueblo [peoples who] constructed this cliff dwelling and the others like it at Mesa Verde were driven to these defensible positions by 'increasing competition amidst changing climatic conditions'. Cliff Palace was abandoned by 1300, and while debate remains as to the causes of this, some believe a series of megadroughts interrupting food production systems is the main cause.

"Sandstone, mortar and wooden beams were the three primary construction materials for the cliff dwellings. The Ancestral Puebloans shaped each sandstone block using harder stones collected from nearby river beds. The mortar between the blocks is a mixture of local soil, water and ash. Fitted in the mortar are tiny pieces of stone called 'chinking'. Chinking stones filled the gaps within the mortar and added structural stability to the walls. Over the surface of many walls, the people decorated with earthen plasters of pink, brown, red, yellow, or white -- the first things to erode with time.

"The Ancestral Puebloans were experienced builders. The walls of the cliff dwelling were built straight and tall, laid up with carefully shaped stones. ...Autumn [was] the villagers’ busiest time of year. On the mesa top, men [harvested] their crop of corn, beans, and squash. They reached their fields by hand-and-toe-hold trails pecked into the canyon walls. Some of them [stayed] in the dwelling, spreading the crops on a roof top to dry. These are the stores that [would] see them through the long winter and even the next year or two if there [was] drought. [An everyday scene in autumn might include] women grinding corn, old men sitting in the sun and telling stories, hunters off on a hunting expedition, children scampering about, and domesticated dogs and turkeys roaming the courtyards."

The cliff palace is undoubtedly a testament to the possibilities of a lively human culture, regardless of whether we set some "barbarous" past apart from our pristine present.

To be very much here is something to hunger for at any point in history.

We have our own rock houses over here at Kinver Edge.

Thanks very much for that, WB. Useful local knowledge indeed. One may perhaps more easily imagine feeling "at home" among the troglodytes than among the contemporary smarties in highrises with their dumbfuck Smartphones.

Unrestored Rock House @ Kinver Edge, Staffordshire (photo by Mjr74)

"Kinver Edge is home to the last troglodyte dwellings occupied in England, with a set of complete cave-houses excavated into the local sandstone. One of the rocks, 'Holy Austin', was a hermitage until the Reformation. The Holy Austin rock houses were inhabited until the 1950s."

Holy Austin Rock House at Kinver Edge, Staffordshire (photo by Nick Garrod)

"This is the remains of a 19th century rock house at Kinver Edge in Staffs. There are three levels of houses, this is the upper unrestored level. The lower level houses have been restored. These were inhabited until the 1950's [by] England's last cave dwellers. Really interesting for both its geology and history, Kinver Edge is a curious hill ridge or escarpment created from sand when this area was a desert over 200 million years ago. There are several interesting geological outcrops here, such as Nanny's Rock. It is now a popular spot for walking, with lots of open heath and woodland to explore. For centuries people dug into Kinver Edge's soft sandstone to create their homes, the last cave dwellers only moved out in the 1950s. One of the rock houses has been restored so you can imagine living here in Victorian times."

It’s hardly a secret that all civilizations collapse and die, not just those in the Americas. Sumer? Gone. Babylon? Bye-bye. Greece and Rome? Ciao bella. Industrial capitalism with a heavy overlay of shopping? Tube time. Exit here.

As for “never getting beyond the tribal/nomadic stage”—better that we hadn’t. The Anasazi “knew what the face of nature is there to conceal,” something that denizens of our hyper-urbanized “cultcha”—in thrall to smarty-pants phones, pods, pads, and other electronica—fail to understand. There is so much they fail to understand about subsistence living [read: living with just enough].

When climate change made their way of life untenable, the people at Mesa Verde packed it in, walked away some speculate, returned to a hunting and gathering life. They backed away from “civilization.” For us, that long ago ceased to be an option. “ . . . gone very much gone.”

"There is so much they fail to understand about subsistence living [read: living with just enough]."

Greed, redundant accumulation, shoptilya drop, then jump in the car and run down to the market for more, more, more: by these signs will our epoch be remembered... but hopefully not for long.

Will there be a burial ground vast enough to hold the billions of precious, "special" images of "our time" remaining in all those millions of playing-card-size plastic slabs jettisoned into the rubbish heap of history to litter the ground and make it useless for any living beings unlucky enough to come after us?

Our "significant cultural achievement": developing the longest boarding-house-reach in the history of the planet. And nothing of any value left after us, to walk away from.

It's been a while now since I've managed to make it out into the streets, but as a souvenir of that last wobbly expedition I've kept a Street Spirit paper handed me by a denizen of the urban shadows, one of those numberless anonymous contemporary nomads. In it there's a poem, which reads in part:

would you sit by me

if I had no home

or have me colonized away

a "leper" of the usa

would you take me

in your arms and weep

if you found

an untouchable like me

murdered on your streets

would you come

to the city morgue

to collect my no name ashes

one of society's throwaways

"see I have carved you

out of the palm of my hand

you are precious to me"

must have been written

for someone else

not the lower caste like me

tonight if I'm lucky I'll die

and won't be a piece

of garbage beneath your feet

that no one wants to see

-- from "lepers of the usa"

by Judy Joy Jones

Living in a country where one’s almost always within a stone’s throw of stony reminders of its past, I appreciate this post most dearly.

I spent seven years researching and writing a book that looked at Native American (Indian) prehistory and how it was framed in 18th and 19th century American lit. I looked mostly at the Iroquois and their predecessors in New York. Note here I used a lot of material from archaeology.

As this blog shows, we tend to see views that congregate around two polarities: Indian life was unspeakably brutal and barbaric or Indian life was idyllic and an alternative to Europe (a legacy of Romanticism). From what I found, neither will suffice. To a middle American, sure Indian life would seem often barbaric (so would life in 13th century Germany). But even in North America there were levels of social and economic organization that are a marvel by modern standards and using a vastly different model than the one we have inherited. There were long stretches of prosperity for many groups. The best thing I can suggest is that we try to shed our blinders and see Indian culture on its own terms, as difficult as it is, maybe learning something valuable.

Also - climatology and anthropology indicate some sort of climatic event impacted North America circa the 13th century. In New York, there might have been years when summer did not come, a radical cold spell. The pre-Iroquois quickly moved from open settlements by rivers to fortified stockades on hilltops and evidence of general unrest can be found in places across the continent during that era.

Vassilis,

These stones sinking into time, how far will they drag me with them?

Seferis: Mythistorema (tr. Keeley & Sherrard)

De Villo,

This is spot on:

"...there were levels of social and economic organization that are a marvel by modern standards and using a vastly different model than the one we have inherited. There were long stretches of prosperity for many groups. The best thing I can suggest is that we try to shed our blinders and see Indian culture on its own terms, as difficult as it is, maybe learning something valuable."

Those blinders have enveloped this cargo-cult culture of ours like the blindfold of a prisoner who is about to be executed, yet thinks he is watching a brilliant movie in which he is at once the director and star. Our society creates a wall that cuts us off from the past and from each other. So much is taken for granted, technologies that did not exist yesterday are put in place today and by tomorrow are accepted as natural and inevitable. The assumptions may prove fatal.

I think there is probably a good deal of truth in the hypothesis that a climate event was decisive in causing the Pueblo peoples to pick up and go, leaving little trace. As you say, their culture was very likely a great deal more sophisticated than has been suspected -- judging these things by our standards of use and convenience is an extension of our larger self-deception, itself largely the product of a hubristic arrogance. When things begin to come apart, we won't have those peoples' ability to travel light and move with the winds. We'll be stuck with what we've made, caught in the trap we've built for ourselves, I'm afraid. Individuals who have chosen to think and act independently may well be swept away in the tide. Societies and empires rise and fall, nothing is absolute, nothing lasts forever. To detach oneself from the movements of history is impossible in any epoch, never more so than now.

My grandfather was an art historian who specialized in pre-Columbian art. He used to say (about some works of art, but maybe it applies to some cities, too), "We don't know what it meant, but we know it meant something."

Tom, well-said on the isolating qualities of modern life that detach us from the archaic and many other things.

My arduous research led me to a similar conclusion that you clearly reached in your own writing: For those interested in American epics and the roots of how we got here (like Olson or Williams), take a look at the fur trade. An empire of skin indeed!

An earlier comment in the stream suggested depletion of resources ended some Indian cultures. In most cases, that's theory. The Indians managed the natural resources of N. & S. America very well for 10,000 years. The Euro-American reign stripped and gutted the place in about, what?, three centuries.

The Iroquois would stay in a settlement for a few decades. Nearby firewood supplies, game, soil fertility would become depleted. "Traveling light" as you say, they would establish a new settlement a few miles away and the old location would be left to renew itself.

Is that conspicuous over-consumption?

"We don't know what it meant, but we know it meant something."

There is a modesty and an inquisitive curiosity and indeed, a wisdom, in that.

Alas it's far more common nowadays to suppose that we know everything -- and that it all meant (or means) absolutely nothing. (Unless, that is, money can be made in the acquiring of it.)

And yes, I think the history of the Northwest Coast fur trade is a parabolic encapsulation of the history of white men on this continent. Take what's there by hook or crook, sell it off, use it up -- and then move on to the next theatre of extraction.

The native cultures that were thus manipulated, exploited and forever changed during that brief historical period of the pursuit of "soft gold" had sustained themselves for thousands of years in balance with their natural environment.

Afterwards, what remained? Totem-pole trading posts for white world tourists?

Post a Comment