.

View towards the Old Town and the Southern part of the city, Stockholm: cyanotype by Carl Curman, 1900 (Swedish National Heritage Board)

To believe in a God means to understand the question about the meaning of life.

A possum and a movie camera, north Australia: photographer unknown, 13 August 1943 (Australian War Memorial Collection)

To believe in a God means to see that the facts of the world are not the end of the matter.

An audience wearing special glasses watching a 3D "stereoscopic film" at the Telekinema on the South Bank, London, during the Festival of Britain: photographer unknown, 11 May 1951 (National Archives, UK)

To believe in God means to see that life has a meaning.

A woman with slabs of bacon tied to her feet standing in a giant skillet holding an enormous spatula and smiling at the crowd, Chehallis, Washington: photo by Vern C. Gorst, c. 1929-1932 (University of Washington Libraries Digital Collections)

The world is given me, i.e. my will enters into the world completely from outside as into something that is already there.

Riverview Cemetery accident, Richmond, Virginia: photo by Adolph B. Rice Studio, 27 July 1961 (Rice Collection, Library of Virginia)

(As for what my will is, I don't know yet.)

Collision between two engines, Bay of Quinte Railway, Ontario: photographer unknown, 1892 (Musée McCord Museum)

That is why we have the feeling of being dependent on an alien will.

Eastern Air Liner crash landing, Curles Neck Farm, Virginia: photo by Adolph B. Rice Studio, 21 July 1951 (Rice Collection, Library of Virginia)

However this may be, at any rate we are in a certain sense dependent, and what we are dependent on we can call God.

One wheel motorcycle, invented by an Italian, M. Goventosa of Udine; maximum speed, 150 km per hour [93 mph]: photographer unknown, 1931 (Collectie Spaamestad, Nationaal Archief, The Netherlands)

In this sense God would simply be fate, or, what is the same thing: The world -- which is independent of our will.

Oil burning installations in the course of erection: photographer unknown, February 1924 (Wallsend Slipway and Engineering Company Limited Collection, Tyne and Wear Archives and Museums)

I can make myself independent of fate.

Girls skipping at an athletics carnival: photographer unknown, c. 1900 (Tyrrell Photographic Collection, Powerhouse Museum, Sydney)

There are two godheads: the world and my independent I.

Great Squishing Drama of 1959, Dromod, County Leitrim: photographer unknown, February 1959 (National Library of Ireland)

I am either happy or unhappy, that is all. It can be said: good or evil do not exist.

Rail Station, Cork: photographer unknown, after 2 February 1893 (National Library of Ireland)

A man who is happy must have no fear. Not even in the face of death.

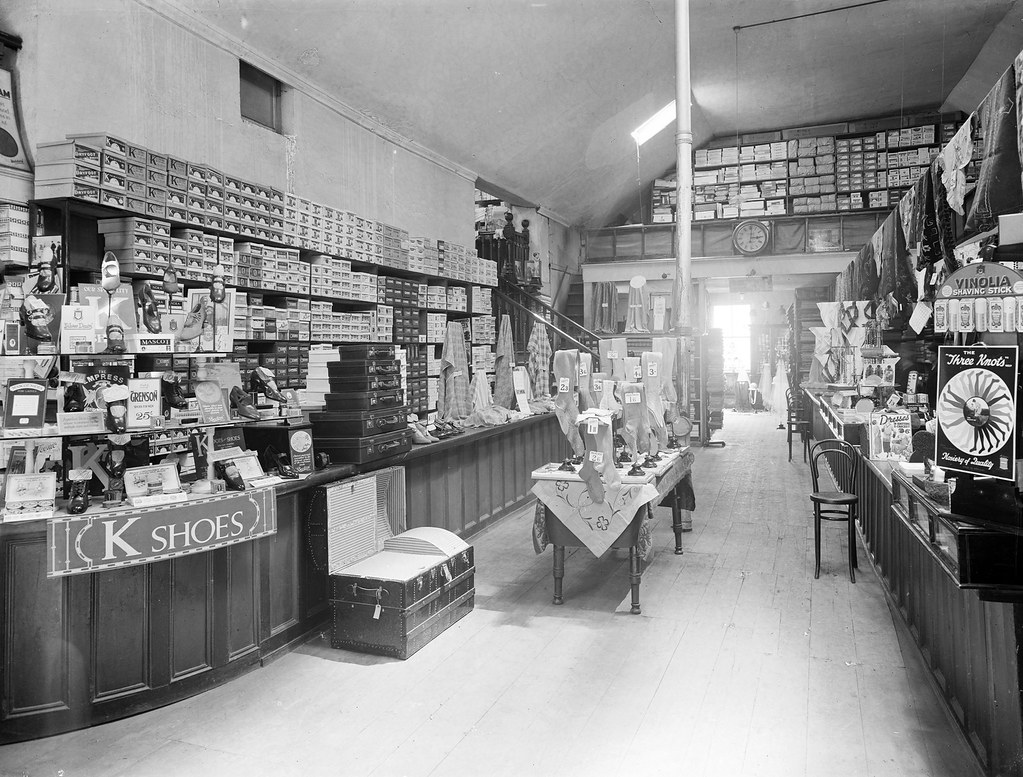

Hadden's Drapery, Dungarvan: photographer unknown, 4 May 1925 (National Library of Ireland)

Only a man who lives not in time but in the present is happy.

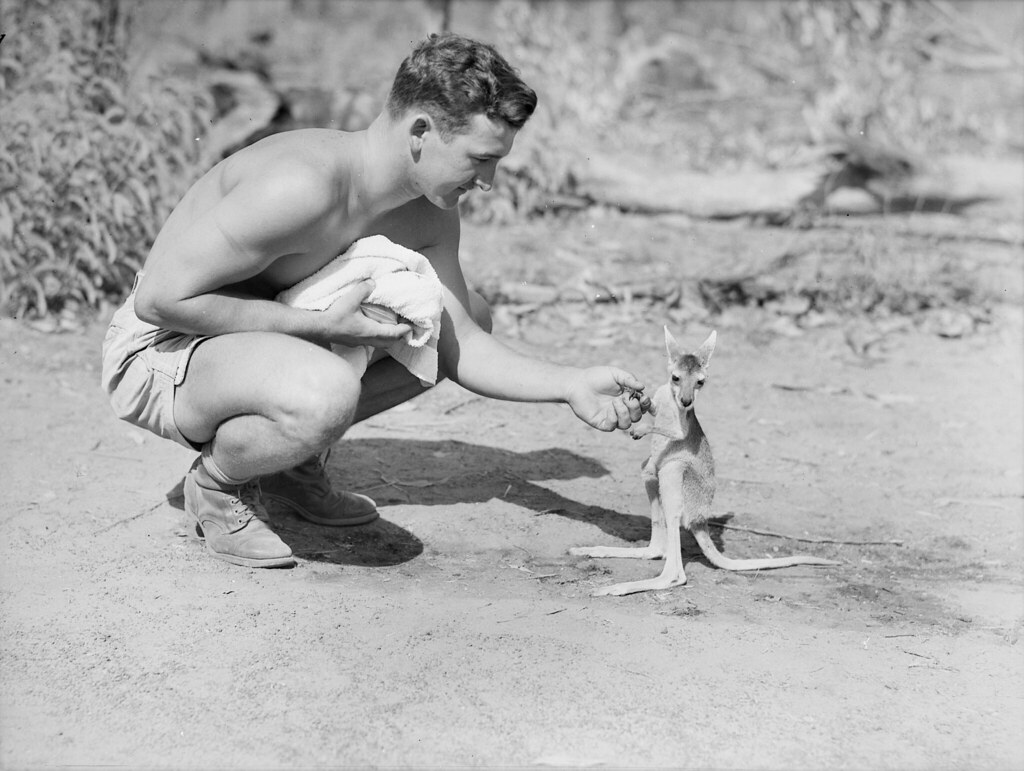

An American soldier with his pet joey: photo by John Earl McNeil, 10 September 1942 (Australian War Memorial Collection)

For in life in the present there is no death.

Harborview Trauma Center, Seattle: photographer unknown,

3 May 1999 (Fleets and Facilities Department Imagebank Collection, Seattle Municipal Archives)

Death is not an event in life. It is not a fact of the world.

Death is not an event in life. It is not a fact of the world.

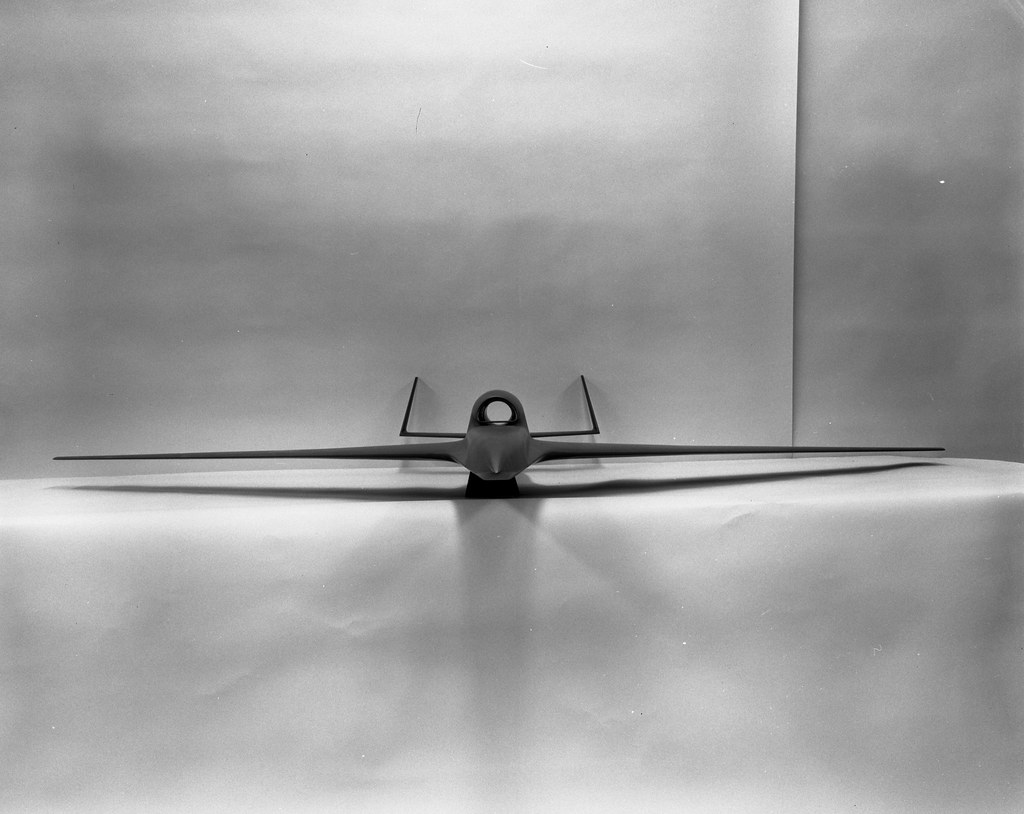

Early Model 154 wind tunnel model aerial drone: photographer unknown. n.d. (Ryan Aeronautical Collection, San Diego Air and Space Museum

If by eternity is understood not temporal duration but non-temporality, then it can be said that a man lives eternally if he lives in the present.

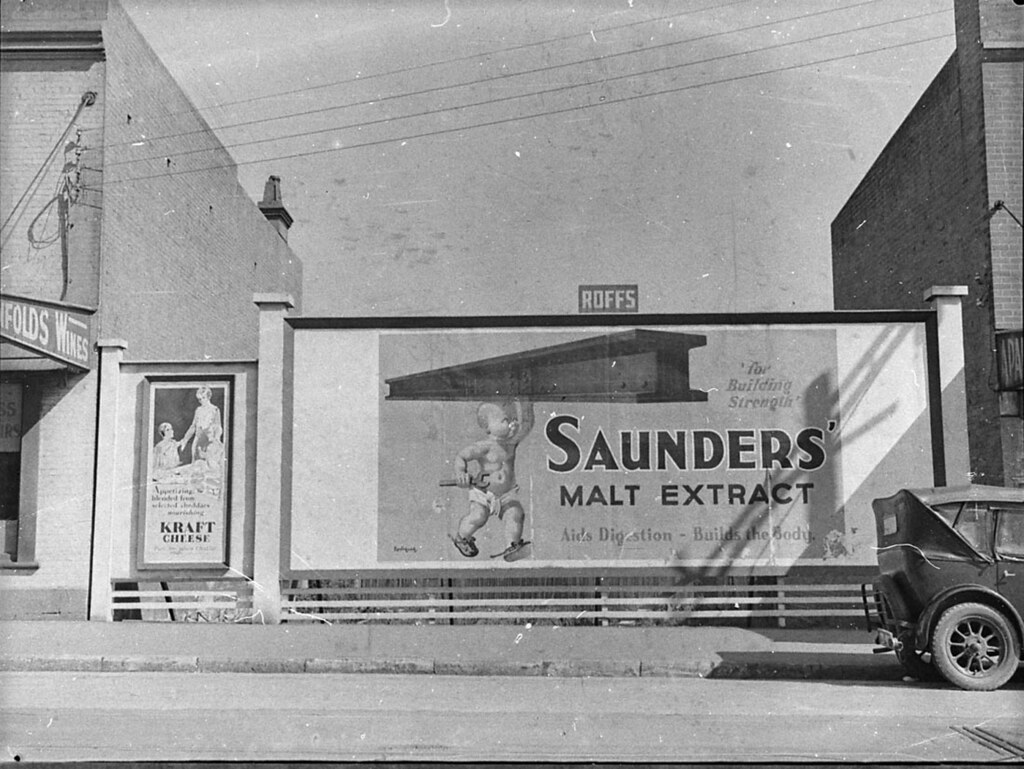

Billboard advertising Saunders' Malt Extract, Sydney: photo by Sam Hood, c. 1930 (State Library of New South Wales)

In order to live happily I must be in agreement with the world. And that is what "being happy" means.

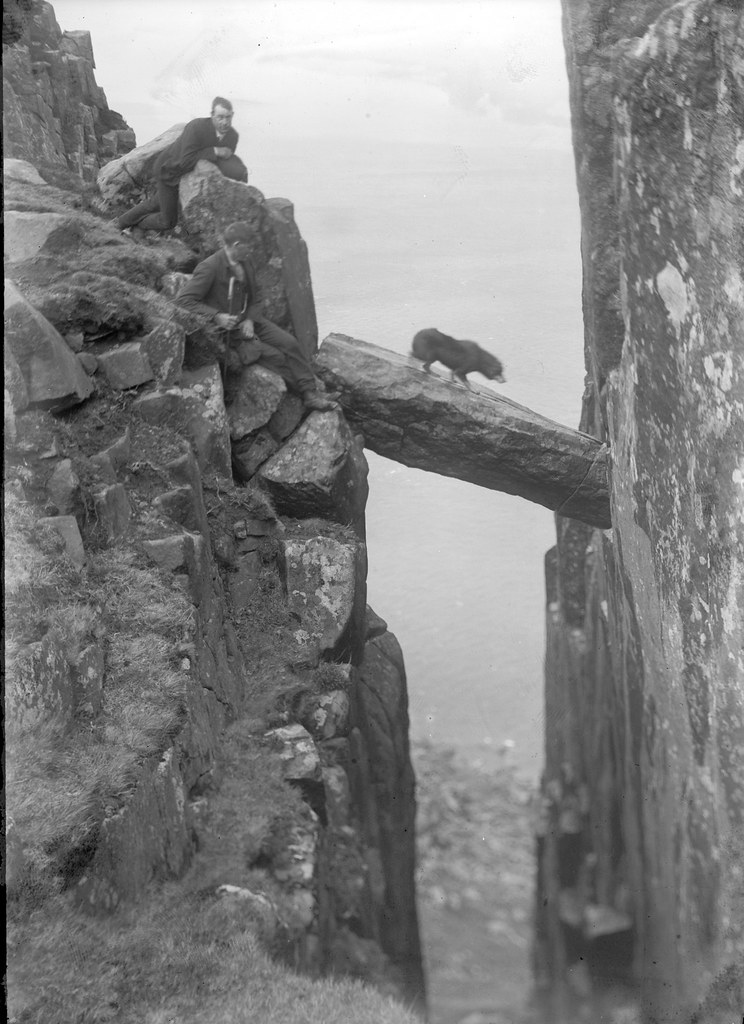

Gray Man's Path, Fair Head, Ballycastle, County Antrim, Northern Ireland: photographer unknown, c. 1920 (National Library of Ireland)

I am, then, so to speak, in agreement with the alien will on which I appear dependent. That is to say: "I am doing the will of God".

European champion diver Natalia Kusnetzova during her jump from the 10-meter board at the European Swimming Champinships: photo by Ron Kroon/Anefo, 25 August 1966 (Nationaal Archief, The Netherlands)

Fear in the face of death is the best sign of a false, i.e. a bad, life.

Young lady having liquid hosiery applied to her legs in a store, Brisbane: photographer unknown, September 1941 (State Library of Queensland)

When my conscience upsets my equilibrium, then I am not in agreement with Something. But what is this? Is it the world?

Passers-by in wind, Karl-Marx-Allee, Berlin: photo by Ralph Hirschberger, 1990 (Deutsches Bundesarchiv)

Certainly it is correct to say: Conscience is the voice of God.

Wind buffets the bride's veil and train at the wedding of Cyril Ritchard and Madge Elliott, St Mary's Cathedral, Sydney: photographer unknown, 16 September 1935 (National Library of Australia)

For example: it makes me unhappy to think that I have offended such and such a man. Is that my conscience?

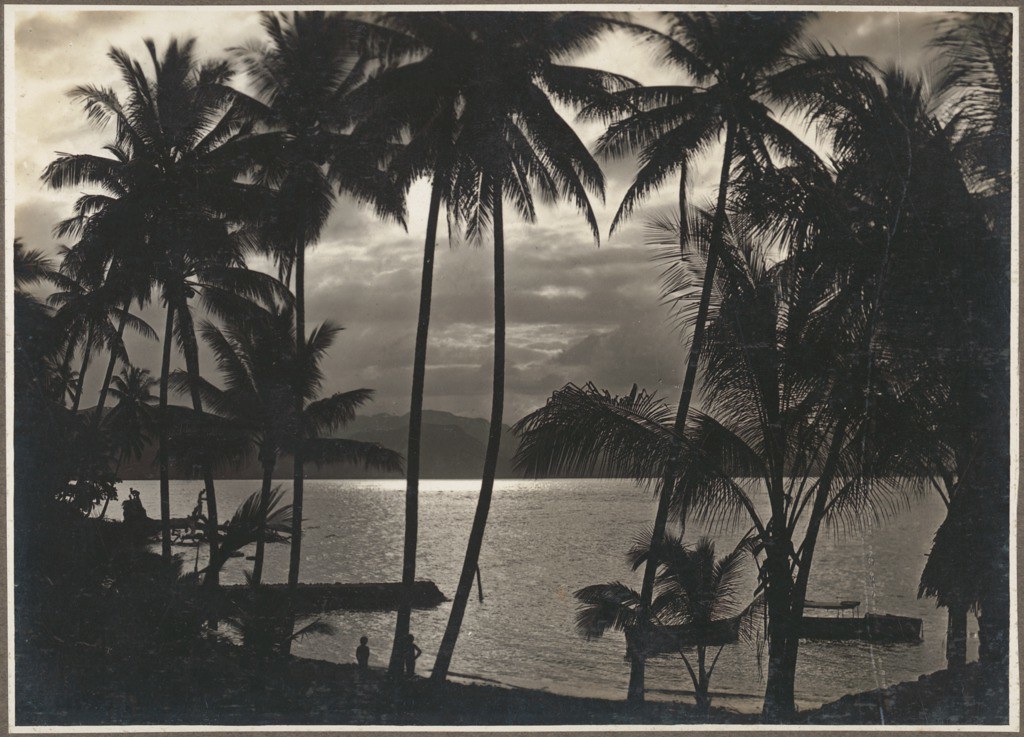

Sunset, Boianai (1): photo by frank Hurley (1885-1962), c. 1921, from photograph album of Papua and the Torres Strait (National Library of Australia)

Can one say: "Act according to your conscience whatever it may be"?

Fonte Luminosa, Lisboa, Portugal: photo by Horácio Novais (1910-1988), after 1948 (Biblioteca de Arte-Fundação Calouste Gulbenkian)

Live happily!

Kookaburras: photo by Kerry Photo, Sydney, c. 1900 (Tyrrell Photographic Collection, Powerhouse Museum, Sydney)

25 comments:

Sometimes the conjunction of images and comments can make one perfectly happy

Tom,

What would Wittgenstein have thought of his lines interspersed with these pictures? Perhaps smile -- when he got to "Live happily!" followed by those Kookaburras.

3.8

light coming into sky above black plane

of ridge, song sparrow calling in field

in foreground, sound of wave in channel

the picture before I see it,

present that a moment

changes, if then more color,

without “limits” form

whiteness of sun in clouds above ridge,

line of pelicans flapping toward point

Great one, Tom! Love that cyanotype. Is the sun setting or rising? In “reality”, as they like to say, any meaning in the world is only the meaning we put there . . . or fail to. The world has meaning when we give meaning to it. We play our parts in the concrete and the transitory; let’s call it Escape from Duality: The Sequel.

"However this may be, at any rate we are in a certain sense dependent, and what we are dependent on we can call God."

Last night I was reading Huston Smith on Islam. He talks about how islam means surrender and quotes William James: "When all is said and done, we are in the end absolutely dependent on the universe; and into sacrifices and surrenders of some sort, deliberately looked at and accepted, we are drawn and pressed as into our only permanent positions of repose."

The post began with the aeronautical images, the crazy danger of flying. Never quite leaves your mind. Even when you're not.

Remembering LW had set out to be an aeronaut.

Then it had occurred to him him that aeronauts might be complete idiots, in a philosophical sense.

That bothered him, of course.

He went to Russell seeking career confirmation.

Am I a complete idiot? he enquired.

A brilliant montage. The words make as much sense about god as it is possible to do given the famous injunction to let silence have the last word on. The intersection of the images, and the coloration given by the title, make this a particularly memorable example of Tom Clark's genius. -- DL

Gracias to Ron, David G., Stephen, Hazen, Lord Charlie, and to David L. (for the nod over at Best Am Po).

David's post, by the way, may be found here.

Thank God for Ludwig.

I've always felt that he had more of a sense of humour than people give him credit for. There's a foolishness about his enquiries - asking the questions we keep from our tongues in embarrassment. He loves to wind up the tidier logicians with those plainly worded statements pointing out the fissures with a boy's delight.

Thank you, TC, for this. I'm sure he would have loved the possum with the camera.

All the photographs priceless but the one that sticks in my craw is the one showing the woman greasing the giant skillet in Chehalis, Washington; I never knew till now how close I was—a mere 50 miles— to the source of the phrase bringing the bacon home.!

So it's out of the frying pan into the thought of the charming little godheads dancing on the Sydney pier, then.

The cinematic possibilities in the photo-sequencing here seemed endless. This project felt like making a silent film, with LW doing the captioning; his "straight face" succeeding, almost, in putting a straight face on the several absurdities and curiosities in the images.

The possum playing at making pictures might well have emerged from a Wittgenstein "hypothetical", indeed. The movie made by the possum would perhaps have to be viewed through those extra-dimensional glasses, in order to avoid being squished by that train. It might even be viewed at a drive-in, with the possible drawback that the show might end with a trail of tire-tracks over the graves of the ancestors.

The visual telling of stories in an interesting pastime. The propositional minimalism of Wittgenstein's notebooks seem to beg for a rhythm of pause and reflection; his statements have the boiled-down essentialism of thinking that has no time to waste. Remembering he was, at the time of making the notes, an officer of the Austrian Army, and had seen significant action on the Russian front.

Thus his quasi-religious meditations on God, life and death suggest an urgency that might not have attended his thought were he back in rooms at Trinity, at the time of composition.

A delightful back-channel note from Annie Wyndham echoes our delight in those Kookaburras, and remarks also on another of the curiosities in the photo-selection:

"I never heard of liquid hosiery though, that's a new one. And I'm old enough to remember nylons that had seams down the middle of the back leg. I heard someone once list, as one of mankind's most important inventions (alongside the wheel), "pantyhose", ha ha."

The "liquid hosiery" phenomenon, of course, resulted from wartime shortages.

The Aussies were not the only consumers of liquid hosiery.

World War II poster for British "liquid silk stockings"

I enjoyed reading this...

Dear T: This one was especially wondrous. I love the Shaw clip, but wonder what that first sentence was that so convinced him of W's not being "a complete idiot."

Terry, many thanks.

By the way, that's actually not Shaw but Bertie Russell.

Russell was regarded as the premier philosopher in Cambridge when Wittgenstein arrived.

LW was accustomed to skipping the preliminaries and going straight to the heads of the town.

Many have wondered about that sentence.

Did Russell himself remember it??

Russell wrote to Ottoline Morrell in 1916:

"Do you remember that at the time when you were seeing Vittoz I wrote a lot of stuff about the theory of knowledge which Wittgenstein criticised with the greatest severity? His criticism, tho' I don't think you realised it at the time, was an event of first rate importance in my life, and affected everything I have done since. I saw that he was right, and I saw that I could not hope ever again to do fundamental work in philosophy. My impulse was shattered, like a wave dashed to pieces against a breakwater. I became filled with utter despair, and tried to turn to you for consolation."

And there is this passage on LW in Russell's 1959 Autobiography:

"He was perhaps the most perfect example I have known of genius as traditionally conceived, passionate, profound, intense, and dominating. He had a kind of purity which I have never known equalled except by G.E.Moore.

"He used to come to see me every evening at midnight, and pace up and down the room like a wild beast for three hours in agitated silence. Once I said to him: 'Are you thinking about logic, or about your sins?' 'Both', he replied, and continued his pacing. I did not like to suggest it was time for bed, for it seemed probable both to him and to me that on leaving me he would commit suicide."

And finally, Russell, from My Philosophical Development (1959), a last word and a somewhat different view:

"There are two great men in history whom he somewhat resembles. One was Pascal, the other was Tolstoy. Pascal was a mathematician of genius, but abandoned mathematics for piety. Tolstoy sacrificed his genius as a writer to a kind of bogus humility which made him prefer peasants to educated men and Uncle Tom's Cabin to all other works of fiction. Wittgenstein, who could play with metaphysical intricacies as cleverly as Pascal with hexagons or Tolstoy with emperors, threw away this talent and debased himself before common sense as Tolstoy debased himself before the peasants -- in each case from an impulse of pride. I admired Wittgenstein's Tractatus, but not his later work, which seemed to me to involve an abnegation of his own best talent very similar to those of Pascal and Tolstoy."

Thanks for all this further elucidation, Tom. I meant Russell, not Shaw, and now I wonder why I made that mistake. Old brain disorder.

Terry,

Know what you mean. It's when the old ones bump into the new ones that... what? Mankind inches forward??

Though he had left the Tractatus far behind by the time he died, this post brought to mind his final words:

"Tell them I've had a wonderful life."

Chris,

That's of course a wonderful thing for him to have said (and quite characteristic of him) -- but perhaps not such an easy thing for them to believe, if they had known him.

Oh yes, entirely characteristic. And (therefore) entirely problematic.

In the later work there is less about God and happiness, although they don't disappear completely. There is a greater focus on the sources of the power of philosophical problems, rather than their solutions. This leads to some of his most fruitful lines of thought, e.g. "The aspects of things that are most important for us are hidden because of their simplicity and familiarity."

Chris,

I can't help thinking of the Tractatus as a product of the pressure of experience -- including and especially the world historical experience of suffering in war. This, reduced to the kind of compressed message one might carry as an amulet into (spiritual) battle.

And then, later, Cambridge again, and god knows what smoldering inner fires, banked (repressed) so much of the time, and these experiences -- the stifled love affair, the hot-under-the-collar philosophy agitations (see: the Karl Popper "poker" incident) -- all of it then emerging in the transformed version of an entirely different philosophy.

Not to be too impossibly reductive and patronising but -- Freudian concept of sublimation and displacement?

One must stand in awe before the saintly genius, and attempt at the same time to feel compassion for the entirely human being at the centre of this impossible nexus -- perhaps the last of the great pre-postmodern pre-ironic contributors to our most vital intuitive senses of what it is to be a person, to live in the world, to have a mind and use language.

Oh Tom, do you want to talk about Freud and Wittgenstein? Such a great topic.

But before we get to that, let's first talk about how reason is related to emotional life.

While Freud was undoubtedly sometimes reductive and patronizing, concepts like sublimation and displacement can also play a wonderfully liberating role.

L.W. sometimes sounds very post-modern in the later work. He said he was practicing "one of the heirs of the subject that used to be called philosophy". But you're quite right that he thought of himself as not modern at all. "This book is written for such men as are in sympathy with its spirit. This spirit is different from the one which informs the vast stream of European and American civilization in which all of us stand. That spirit expresses itself in an onwards movement, in building ever larger and more complicated structures; the other in striving after clarity and perspicuity in no matter what structure."

Chris,

Not to worry overmuch about defining a pseudo-critical term as ephemeral as a fanciful wig-bubble, but I think perhaps that comment of LW's might well fit as an approximate summary of the fish-nor-fowl creature called postmodernism if one allows into it the following square-bracketed emendation:

"That spirit expresses itself in an onwards movement, in building ever larger and more complicated [and obfuscating] structures..."

The combination of fascination and distrust with which LW seems to have received Freud's work suggests many of the familiar complications of a Viennese family feud.

This seems to have been the foundation of the dispute for LW:

‘He has not given a scientific explanation of the ancient myth. What he has done is to propound a new myth. The attractiveness of the suggestion... is just the attractiveness of a mythology.’

LW appears to have grasped the poetic/symbolic "charm" of Freudian theory -- and at the same time to have distrusted it, as deeply "unscientific".

Ray Monk has made a heroic attempt to place the two thinkers into one virtual intellectual space, and to encourage them to a conversation of sorts based on a common engagement with "thinking in pictures".

Ray Monk: "Wittgenstein's passion for looking, not thinking"

A bit of the Monk article:

'“Thinking in pictures,” Sigmund Freud once wrote, “stands nearer to unconscious processes than does thinking in words, and is unquestionably older than the latter both ontogenetically and phylogenetically.” There is, in other words, something primordial, something foundational, about thinking visually...

'For Wittgenstein, to think, to understand, was first and foremost to picture. In conversation with his friends, he several times referred to himself as a “disciple” or “follower” of Freud and many people since have been extremely puzzled what he might have meant by this. I think Freud’s remark quoted above might provide the key here, that it might have something to do with the emphasis one finds in Freud on the primordiality of “thinking in pictures”.

'Like Freud, Wittgenstein took very seriously indeed the idea that our dreams present us with a series of images, the interpretation of which would reveal the thoughts we have relegated to the unconscious parts of our minds. “If Freud’s theory on the interpretation of dreams has anything in it,” Wittgenstein once wrote, “it shows how complicated is the way the human mind represents the facts in pictures. So complicated, so irregular is the way they are represented that we can barely call it representation any longer.”'

Hello there, I've just found this blog by accident, having only found Ludwig Wittgenstein by accident a couple of months previous. I'm returning to a career I left a decade ago in Electronics, and a friend gave me a copy of Tractatus Logicus, to blow my mind with how Ludwig had laid out the truth-tables upon which the whole enterprise rests, in hardware terms (we have only arrays of data in binary form, when you get right down to it, and the operations "and", "or", "not", with everything else resting on these foundations). I'm learning about software at the moment, in particular "object-oriented programming", and who do I find, 90 years ago, telling me how I should think of an object. To now find out that he went on to have things to say about God, well, if his form is anything to go by, it will be certainly worth reading...

This is an arresting and a thought-provoking and a joy-giving post, so thank you (and thanks Ludwig!).

Regards,

Tom Eile.

Hello Tom.

I think this is further proof that LW's work was so far ahead of its time that we haven't yet caught up with it.

But there is great pleasure in trying...

Post a Comment