.

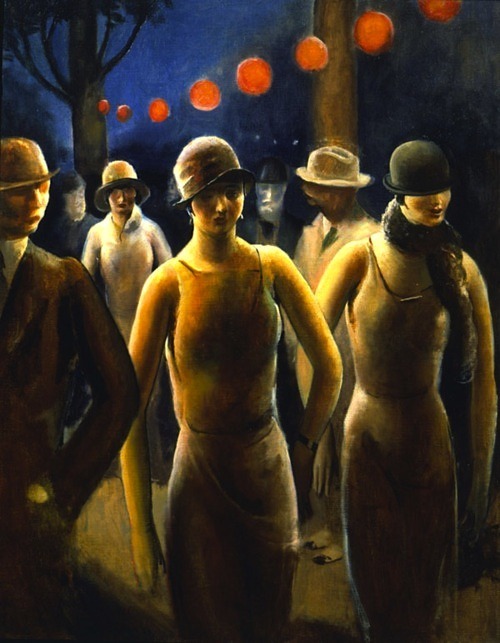

| The Flapper: Guy Pène du Bois, 1922, oil on board, 63.5 x 50.8 cm (Weatherspoon Art Museum, University of North Carolina, Greensboro) | ||||||||||

By modernity I mean the transitory, the fugitive, the contingent which make up one half of art, the other being the eternal and the immutable.

Charles Baudelaire, in The Painter of Modern Life, 1859, translated by Jonathan Mayne

"I've decided," began Bernice without preliminaries, "that maybe you're right about things -- possibly not. But if you'll tell me why your friends aren't -- aren't interested in me I'll see if I can do what you want me to."

Marjorie was at the mirror shaking down her hair.

"Do you mean it?"

"Yes."

"Without reservations? Will you do exactly what I say?"

"Well, I ---- "

"Well nothing! Will you do exactly as I say?"

"If they're sensible things."

"They're not! You're no case for sensible things."

"Are you going to make -- to recommend ---- "

"Yes, everything. If I tell you to take boxing lessons you'll have to do it. Write home and tell your mother you're going to stay another two weeks."

"If you'll tell me --- -"

"All right -- I'll just give you a few examples now. First, you have no ease of manner. Why? Because you're never sure about your personal appearance. When a girl feels that she's perfectly groomed and dressed she can forget that part of her. That's charm. The more parts of yourself you can afford to forget the more charm you have."

"Don't I look all right?"

"No; for instance, you never take care of your eyebrows. They're black and lustrous, but by leaving them straggly they're a blemish. They'd be beautiful if you'd take care of them in one-tenth the time you take doing nothing. You're going to brush them so that they'll grow straight."

Bernice raised the brows in question.

"Do you mean to say that men notice eyebrows?"

"Yes -- subconsciously. And when you go home you ought to have your teeth straightened a little. It's almost imperceptible, still ---- "

"But I thought," interrupted Bernice in bewilderment, "that you despised little dainty feminine things like that."

"I hate dainty minds," answered Marjorie. "But a girl has to be dainty in person. If she looks like a million dollars she can talk about Russia, ping-pong, or the League of Nations and get away with it."

"What else?"

"Oh, I'm just beginning! There's your dancing."

"Don't I dance all right?"

"No, you don't -- you lean on a man; yes, you do -- ever so slightly. I noticed it when we were dancing together yesterday. And you dance standing up straight instead of bending over a little. Probably some old lady on the side-line once told you that you looked so dignified that way. But except with a very small girl it's much harder on the man, and he's the one that counts."

"Go on." Bernice's brain was reeling.

"Well, you've got to learn to be nice to men who are sad birds. You look as if you'd been insulted whenever you're thrown with any except the most popular boys. Why, Bernice, I'm cut in on every few feet -- and who does most of it? Why, those very sad birds. No girl can afford to neglect them. They're the big part of any crowd. Young boys too shy to talk are the very best conversational practice. Clumsy boys are the best dancing practice. If you can follow them and yet look graceful you can follow a baby tank across a barb-wire sky-scraper."

Bernice sighed profoundly, but Marjorie was not through.

"If you go to a dance and really amuse, say, three sad birds that dance with you; if you talk so well to them that they forget they're stuck with you, you've done something.

They'll come back next time, and gradually so many sad birds will dance with you that the attractive boys will see there's no danger of being stuck -- then they'll dance with you."

"Yes," agreed Bernice faintly. "I think I begin to see."

"And finally," concluded Marjorie, "poise and charm will just come. You'll wake up some morning knowing you've attained it, and men will know it too."

Bernice rose.

"It's been awfully kind of you -- but nobody's ever talked to me like this before, and I feel sort of startled."

Marjorie made no answer but gazed pensively at her own image in the mirror.

"You're a peach to help me," continued Bernice.

Still Marjorie did not answer, and Bernice thought she had seemed too grateful.

"I know you don't like sentiment," she said timidly.

Marjorie turned to her quickly.

"Oh, I wasn't thinking about that. I was considering whether we hadn't better bob your hair."

Bernice collapsed backward upon the bed.

F. Scott Fitzgerald (1896-1940): Bernice Bobs Her Hair (excerpt), from Flappers and Philosophers, 1922

Subway Steps: Guy Pène du Bois, oil on canvas, 1926 (Whitney Museum of American Art)

Carnival: Guy Pène Du Bois, 1927, oil on canvas (Whitney Museum of American Art)

Woman with Cigarette: Guy Pène du Bois, 1929 (Whitney Museum of American Art)

Jane: Guy Pène du Bois, c. 1946, oil on canvas, 76.2 x 60.96 cm (Memorial Art Gallery, Rochester)

Girl Reading a Book: Guy Pène du Bois, 1929, oil on canvas

Two Women: Guy Pène du Bois, n.d.

Lady in a Cloak: Guy Pène du Bois, 1927

Cafe Monnot, Paris: Guy Pène du Bois, n.d., oil on canvas (Whitney Museum of American Art)

Shops: Guy Pène du Bois, n.d.

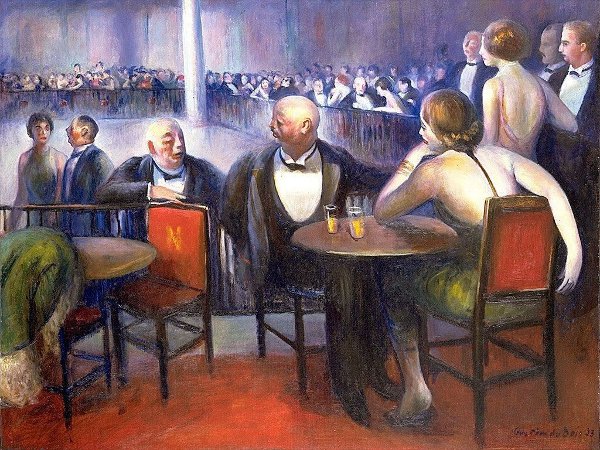

Night Club: Guy Pène du Bois, 1923

Mr. and Mrs. Chester Dale Dine Out: Guy Pène du Bois,1924 (Whitney Museum of American Art)

9 comments:

The Du Bois Family: Life, April 29 1940

Guy Pène du Bois: The Twenties at Home and Abroad: Betsy Fahlman, 2004

This is spectacular also and a wonderful weekend offering. Our daughter Jane is a fitful reader. Last year in 10th grade they assigned her The Great Gatsby, which was a reasonable thing to do, I guess, until they started applying layers of received and testable wisdom, which really dampened whatever spark they were presumably trying to light in her. We kept urging her not to turn off, but to sample Fitzgerald's stories because they're wonderful to read, contain funny and ironic twists, etc., which we thought would grab her the way Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde did. Talented family, the Pene du Bois. I dream of my daughter saying to an interviewer, as Yvonne did, "I learned everything from Father." Unfortunately, the last thing Jane said (when I dropped her off earlier at a practice SAT session) wasn't in that vein. Oh well -- it's a beautiful fall day in Chester County, PA. Curtis

Oh, dear, Curtis. How soon they forget!

By the by, talking of family, Guy's son Billy, who did many children's books (some of them for childish grownups, I guess) was in the Plimpton orbit, back in the day. He was a founding editor and first art editor of The Paris Review.

I did not know that about Billy Pene du Bois and, as an inveterate masthead reader and memorizer, I think that my mind must finally be going. It's great to see all these Guy Pene du Bois paintings assembled and looking so great. After yesterday's post I started reviewing the paintings of his contemporary Kenneth Hayes Miller for comparison. I did my M.A. thesis on Miller (if you don't recall him, which very few people do, he was teacher and mentor to a lot of the better known "14th Street School" artists) and found myself noticing the things I didn't like in his work, both in comparison to some of his talented, better known students, and to Pene du Bois. Miller has a certain extremely weird quality, which means something to me, but it just doesn't sing like Guy Pene du Bois' work does. Curtis

It’s nice to discover Du Bois. Many thanks, Tom. I wonder if DB influenced George Tooker, who also haunted subways, in more ways than one. There is in both a sense of distance, isolation, perfunctory contact; The Existence Machine going into Baudelaire-ian overdrive. It’s contingency all the way down, madam . . .

“Jane” I love. It's especially that shade of blue on the doors that lends so much to the mood. A woman leans forward, pensive, tilting into the picture. There’s tension in that, and a sense of the precarious. The moment’s uncertain. That raking light from high up conceals as much as it reveals.

I like that painting too, the way she does not quite emerge into the light...

Of late the infinitely picky Mr Stephen King has complained that Kubrick's production of The Shining was spoiled by the one-dimensionality of the Shelley Duvall performance. Now there's (in)gratitude!

In any case, she's spot on in Bernice Bobs Her Hair.

If you're to take your place comfortably in the economy you're to learn to forget the mechanics, the insides.

"...a baby tank across a barbed-wire skyscraper": there's an image for you.

Yes, that baby-tank/barb-wire skyscraper image leaps out of context and reminds us of the millions of souls meaninglessly snuffed out in Europe just a few short years before Bernice's pre-tonsorial discombobulation (Coma Berenice?).

Can young Fitzgerald have calculated the effect that abrupt re-adjustment of perspective might be going to have?

One expects not.

But it definitely brings the mind up short, and that's always a shock to the total mechanics.

There's nothing like being crushed into the pavement by the mechanics to keep one from ever not thinking about the mechanics for one full minute.

The insides are soft, the pavement hard.

A comfortable place in the economy would I suppose be akin to a comfortable place in the puppet show.

Of which there's probably always but the one to be had. Pulling the strings, that is.

The baby tanks are currently bot-powered, operated by remote control, and able to maneuver into impossibly tight spaces by means of secret searches, it is widely rumoured.

I'm sorry to learn that Stephen King objects to Shelley Duvall's performance in The Shining, but it reminds me that when works of art are adapted, they're transformed and somebody is bound to be displeased. I'm actually not the biggest Shelley Duvall fan in the world, but I think she's aces in The Shining. Curtis

Post a Comment