.

Scott's Run, West Virginia: Ben Shahn, 1937, tempera on cardboard, 56.5 x 70.8 cm (Whitney Museum of American Art, New York)

Monongah

Mine Explosion

I want to go up to Monongah where they had that big explosion up there. You know, Monongah Mine on Route 19. See, that’s where three hundred and seven men got killed. They don’t even know how many boys, because they wasn’t on the payroll.

Bumping Coal off the Stone

This here is what they call bumping coal off the stone [refers to photo]. You had to undermine this about four feet deep -- you know, get it in there about four feet deep. You see when they get that undermine, then someone would drill a hole there for the coal.

You lived in a coal camp. If you had a boy that was big enough where he could carry a dinner bucket and it wouldn’t drag the ground, then he was big enough to go in the mines. This is a boy here.

Hand Auger

After they get this cut around here, this boy would drill a hole with this hand auger here for when they get ready to tap it. A hand auger like this, see, you had to have. You use to get up on the bench and drill down. If you go in deeper, you can move your bench up see. But then they’d each tap that up, then they’d shoot it, they'd shoot the coal.

Tamping the Hole

[Now for the tamping, what would they actually put in the hole?]

One was dynamite and clay. They use to put clay at the mouth of your place where you would work. You got clay and wrapped it up in paper and you stuck it in a hole and you would tap it in there, see. See I don’t have none of that. Paulette Shine from that museum, the Coal Museum, we’ve got all that down there.

Shooting the Coal

[Shooting the coal means what?]

They’d hook a cable to it and years back they use to call what they have a fuse. They’d light the fuse, then run. Run away, and it would go off. Nowadays they have a cap, what they call a cap. They stick in a stick of dynamite with about a seven foot cord on it, and you’d put it in there and then you’d get your cable and you’d tie it on to this cord. Then you’d stretch it out for about a hundred feet until you’d get around a corner. Then you'd have a little battery. You’d put it on there, and just, you know, pull the wire, and it would go off. Just charge it up and set it off. See here, now they shot the coal down and here’s where they’re loading it in the car -- putting it in there and hand loading it with a shovel.

Shovels

You see they’d have a shovel. They had what they called a number three shovel. Number three shovel is the size down here. And number four shovel was a little bit bigger, number five shovel was bigger yet. You had guys working in mines called steam shovels. We’d call them steam shovel because they could load like a steam shovel. See, they’d load this car up after this coal was shot down; they’d load the car.

Dog Holes

I don’t know if you know where Scott’s Run is or not? Granville right down here? Go past and there was sixty nine mines, sixty-nine mines from here to Granville to up at Cassville. Nineteen of them these mines and the rest of them were called dog holes. Go in there with [? ]and shoot the coal out and sell it.

Nobody had to pay for them. Like you wanted to start a place like that? Well you started with crops out along the river. You’d go up and clean the dirt away and you could start undermining the coal, shoot it and load it up. Yeah, they use to be a lot of dog holes.

Cutting Machine

Then they got a machine -- what they call a cutting machine. Cut coal on the bottom you know. Cut about seven feet deep. They had anywhere from twelve to fourteen feet wide.

Then you didn’t have to undermine it or nothing. You would just clean it, you’d clean that dust from underneath that coal out, where the cut coal was underneath. Clean all that dust out, then you’d shoot it.

Each cut of coal sold about eight cars. That’s about twenty to twenty-two tons of coal. Then you’d clean that some places. You had a cleanup, a cleanup system. You have to clean that whole cut of coal up, regardless of what kind of condition and whether they had a wreck or something and something leaked.

Relay Motor

They had what they called a relay motor. They’d bring end pieces in and put it in the side track and then the horse would get it and bring it to your work place.

Steel Hoppers

Cassvile Mine use to load a hundred steel hoppers a day. That's hand loading. That’s how big it was.

Steel hoppers were what you loaded the coal into, what you see on the road now. They had fifty ton cars and seventy-five ton cars. Cassville was a big coal company. It was owned by some company in Pittsburgh. But we had a coal mine here had a tipple on the other side of the river.

[What’s a tipple?]

Well, see on this hill side? In here they had a mine and a real tipple and they’d load the coal in a bucket and transfer across the river occasionally. That’s where Star City comes in. But then when a cable broke, that would change the mine.

Mine Timbers

See, timbers like that [in a picture] was your warning. If the place was getting bad, going to fall in, them timbers would crack. They would crack and that’s how you got your warning. Then as more weight come down, them posts would just bend and break and fall.

Timbering

Well, [to timber something] you had a saw and an ax. You’d measure, you’d have a little piece of stick, two pieces of stick and slide you know and you made the lintel, then you’d cut that post there and let it leave enough space for that cap piece up there you see. You made it sometimes on what from was left over from the posts. Split the post to make the cap pieces. See here’s where they are doing more timbering, that’s where the place probably got real bad.

Once them posts took weight, you knew it. You could feel the difference. You could tell the difference when you’d come into work the next morning you could tell the difference by looking at the posts.

Now some company’s had what they called timber men. They work separate. You had a real bad place, they’d come in and timber it out.

Coal Loader

See these guys, you see a coal loader. He didn’t make no money unless he loaded coal. What coal you load, that’s what you got paid for.

The coal loader all he would do is load coal and stuff like that. That’s what it looks like here.

Carbide Lights

I started in the mines in the thirties, but this photo was way before the thirties [refers to photo]. See, the miner has a carbide light on. You bought carbide to put in the bottom of the lamp. And the top of the lamp had a little place where you would put water. Then when you want a bigger flame, you’d just flip that water on it and it give you more steam and that flame would come out, see. If was down at the museum, I could show you a carbide light.

Testing for Bad Conditions

See here’s this guy is testing for bad coal. You know you could tell if you heard somebody talking or by the sound of it. If it sounded solid it was all right, but if it boom or something to it, we knew it was bad. We had a regular tapping signal.

A lot of times, your carbide light would tell you if you had air in a mine or not.

It would go dim. It wouldn’t go out. If you didn’t have enough ventilation up in your work place that flame wouldn’t get big at all, then you’d go out there in the fresh air and pop up.

I mean this picture was taken back in the twenties when they tested for gas with canaries.

Horses in the Mines

See I can remember the horses working in the mines. A lot of the times, they’d break a new horse in, I had to go up there and coax the horse. They’d pull a car up and when they was coming back down they didn’t know where to turn off at and I had hell of a time trying to get it to turn off. After all they learned, they were smarter than what the men was driving.

Children in the Mines

A lot of them kids wasn’t over twelve years old. They had them on the tipple picking slate. That was bindering the coal, separating the coal.

You see this little boy that what I was telling you about a while ago wasn’t big enough to carry a bucket. There he is right there. There’s his horse. See, probably that’s a family.

They went in there and loaded the coal and pulled it out and dumped it and car [?] back in there. There was a lot of them in the mines around here.

Factory Train

See I can remember when they had a factory train coming through Osage any time of the day. It came from Pennsylvania to Jimtown, then from Jimtown they could catch a train anywhere. East or West, North or South anywhere they wanted to go. They could catch a train.

The only transportation you had was you had to walk from here to Jimtown, hit the train, go to Morgantown, catch the train coming back. They run about every hour or so. Then there was a lot of car hopping too because that freight train ran all the time up in the hollow and Jimtown. I would jump on it and take a ride to Jimtown and wait and ride it back.

Coal Camp

[You grew up in Coal Camp. What was that like? ]

Well, a lot different than what it is today because everybody knew everybody and if something went wrong in the camp, everybody was there to help you. I can remember when somebody had a baby or something, everybody come up there with chicken. People were more friendly, you know what I mean? They were closer together.

Coal camp is like a big city. It’s got everything coal.

A Burnside stove is a favorite. You’d put that in one room and it would heat the whole house. About four room houses about all they had. Coal stove, yeah. You lived in the coal camp they had a team of washers and a wagon and a guy with all that. If we needed coal, he would go get it and bring it up to your house. Wouldn’t charge a penny for it. I can remember them days real good. You ever see that picture in that museum down there about Liberty? If you ever go down, look at that picture. Liberty’s a little town down there.

Busting and Yellow Dogs

When they started breaking the union, see they throwed the people they call scabs -- we call them scabs -- they took their furniture and throwed it out. And them people, their streets was all full of furniture. [The companies] owned everything.

Now I can remember up here at Osage in Chaplin. Osage had a coal mine there, and Chaplin did on the side of the road. That’s all the water there was. You couldn’t even tell when it was dark here because they had so damn many floodlights shining back and forth, you couldn’t even tell when it was dark. And nobody, let’s see they had a lot of guards. But the trouble didn’t start till they started fooling around with [company guards].

And then that’s when the trouble started, that’s when the trouble started. It was knowed all over the place. It was knowed all over the country.

We use to call [the company guards] yellow dogs. They carried guns and they thought they owned everything. They found out different.

Them old union men that we had are now gone. Yeah they’re all dead. I’m the only one around here. I’m the only one around here knows this stuff. And I try to tell them.

Shifts

[They ran] three shifts. One day shift, afternoon and night. See here, this is Uncle Lloyd right there [refers to photo]. That’s me when I was a kid. All these people are dead here. All of them. Let’s see. This guy lives up in Granville. All these guys here I was raised with in Granville. They’re all gone Second shift. 1940 picture was taken. It shows up good don’t it? Most of them was from around here, not too far. Around Granville, well Granville that’s where the tipple was at. Star City, Evansdale, Brier Hill, just right around here.

This here’s beginning of a shift there everybody’s waiting to go in. You know in them days you had to walk every place. There’s no trips, no nothing. Then in 1945 or something they started bringing loading machines.

There use to be a mine here called Hell Creek brought them in earlier than that. That’s when we were working seven hours a day then, too.

After a shift when we got ready to come home, they’d side-track us or something to bring a load of coal out. That’s when we struck. We got paid for the time we went in till the time we went out. No trouble getting you in there, but getting you out.

River Ferry from Star City and Brier Hill

I can remember a lot of people here worked there from Star City and Brier Hill. They went together and bought themselves a room so they wouldn’t have to pay a nickel to ride the ferry. That ferry, they had a ferry down there you know. High water, low water or not, they’d do it. They’d load that boat on high water up the river a long ways then they’d start across by the time they’d got across they’d be close to the tipple.

Just think. There was everything floating in that river when it was high. Logs, trees and everything. And the river wasn’t very deep then because they didn’t have the locks. The only locks they had was up here. Cause in 1932 I can remember whenever it went dry.

Seasonal Work

We’d set down there on the company store on the porch down there, and then that girl would call us up whether or not we worked tomorrow. If she said there was no work, we’d take off and go off somewheres. Sat around all damn day just to hear whether we worked or not.

I want to go up to Monongah where they had that big explosion up there. You know, Monongah Mine on Route 19. See, that’s where three hundred and seven men got killed. They don’t even know how many boys, because they wasn’t on the payroll.

Bumping Coal off the Stone

This here is what they call bumping coal off the stone [refers to photo]. You had to undermine this about four feet deep -- you know, get it in there about four feet deep. You see when they get that undermine, then someone would drill a hole there for the coal.

You lived in a coal camp. If you had a boy that was big enough where he could carry a dinner bucket and it wouldn’t drag the ground, then he was big enough to go in the mines. This is a boy here.

Hand Auger

After they get this cut around here, this boy would drill a hole with this hand auger here for when they get ready to tap it. A hand auger like this, see, you had to have. You use to get up on the bench and drill down. If you go in deeper, you can move your bench up see. But then they’d each tap that up, then they’d shoot it, they'd shoot the coal.

Tamping the Hole

[Now for the tamping, what would they actually put in the hole?]

One was dynamite and clay. They use to put clay at the mouth of your place where you would work. You got clay and wrapped it up in paper and you stuck it in a hole and you would tap it in there, see. See I don’t have none of that. Paulette Shine from that museum, the Coal Museum, we’ve got all that down there.

Shooting the Coal

[Shooting the coal means what?]

They’d hook a cable to it and years back they use to call what they have a fuse. They’d light the fuse, then run. Run away, and it would go off. Nowadays they have a cap, what they call a cap. They stick in a stick of dynamite with about a seven foot cord on it, and you’d put it in there and then you’d get your cable and you’d tie it on to this cord. Then you’d stretch it out for about a hundred feet until you’d get around a corner. Then you'd have a little battery. You’d put it on there, and just, you know, pull the wire, and it would go off. Just charge it up and set it off. See here, now they shot the coal down and here’s where they’re loading it in the car -- putting it in there and hand loading it with a shovel.

Shovels

You see they’d have a shovel. They had what they called a number three shovel. Number three shovel is the size down here. And number four shovel was a little bit bigger, number five shovel was bigger yet. You had guys working in mines called steam shovels. We’d call them steam shovel because they could load like a steam shovel. See, they’d load this car up after this coal was shot down; they’d load the car.

Dog Holes

I don’t know if you know where Scott’s Run is or not? Granville right down here? Go past and there was sixty nine mines, sixty-nine mines from here to Granville to up at Cassville. Nineteen of them these mines and the rest of them were called dog holes. Go in there with [? ]and shoot the coal out and sell it.

Nobody had to pay for them. Like you wanted to start a place like that? Well you started with crops out along the river. You’d go up and clean the dirt away and you could start undermining the coal, shoot it and load it up. Yeah, they use to be a lot of dog holes.

Cutting Machine

Then they got a machine -- what they call a cutting machine. Cut coal on the bottom you know. Cut about seven feet deep. They had anywhere from twelve to fourteen feet wide.

Then you didn’t have to undermine it or nothing. You would just clean it, you’d clean that dust from underneath that coal out, where the cut coal was underneath. Clean all that dust out, then you’d shoot it.

Each cut of coal sold about eight cars. That’s about twenty to twenty-two tons of coal. Then you’d clean that some places. You had a cleanup, a cleanup system. You have to clean that whole cut of coal up, regardless of what kind of condition and whether they had a wreck or something and something leaked.

Relay Motor

They had what they called a relay motor. They’d bring end pieces in and put it in the side track and then the horse would get it and bring it to your work place.

Steel Hoppers

Cassvile Mine use to load a hundred steel hoppers a day. That's hand loading. That’s how big it was.

Steel hoppers were what you loaded the coal into, what you see on the road now. They had fifty ton cars and seventy-five ton cars. Cassville was a big coal company. It was owned by some company in Pittsburgh. But we had a coal mine here had a tipple on the other side of the river.

[What’s a tipple?]

Well, see on this hill side? In here they had a mine and a real tipple and they’d load the coal in a bucket and transfer across the river occasionally. That’s where Star City comes in. But then when a cable broke, that would change the mine.

Mine Timbers

See, timbers like that [in a picture] was your warning. If the place was getting bad, going to fall in, them timbers would crack. They would crack and that’s how you got your warning. Then as more weight come down, them posts would just bend and break and fall.

Timbering

Well, [to timber something] you had a saw and an ax. You’d measure, you’d have a little piece of stick, two pieces of stick and slide you know and you made the lintel, then you’d cut that post there and let it leave enough space for that cap piece up there you see. You made it sometimes on what from was left over from the posts. Split the post to make the cap pieces. See here’s where they are doing more timbering, that’s where the place probably got real bad.

Once them posts took weight, you knew it. You could feel the difference. You could tell the difference when you’d come into work the next morning you could tell the difference by looking at the posts.

Now some company’s had what they called timber men. They work separate. You had a real bad place, they’d come in and timber it out.

Coal Loader

See these guys, you see a coal loader. He didn’t make no money unless he loaded coal. What coal you load, that’s what you got paid for.

The coal loader all he would do is load coal and stuff like that. That’s what it looks like here.

Carbide Lights

I started in the mines in the thirties, but this photo was way before the thirties [refers to photo]. See, the miner has a carbide light on. You bought carbide to put in the bottom of the lamp. And the top of the lamp had a little place where you would put water. Then when you want a bigger flame, you’d just flip that water on it and it give you more steam and that flame would come out, see. If was down at the museum, I could show you a carbide light.

Testing for Bad Conditions

See here’s this guy is testing for bad coal. You know you could tell if you heard somebody talking or by the sound of it. If it sounded solid it was all right, but if it boom or something to it, we knew it was bad. We had a regular tapping signal.

A lot of times, your carbide light would tell you if you had air in a mine or not.

It would go dim. It wouldn’t go out. If you didn’t have enough ventilation up in your work place that flame wouldn’t get big at all, then you’d go out there in the fresh air and pop up.

I mean this picture was taken back in the twenties when they tested for gas with canaries.

Horses in the Mines

See I can remember the horses working in the mines. A lot of the times, they’d break a new horse in, I had to go up there and coax the horse. They’d pull a car up and when they was coming back down they didn’t know where to turn off at and I had hell of a time trying to get it to turn off. After all they learned, they were smarter than what the men was driving.

Children in the Mines

A lot of them kids wasn’t over twelve years old. They had them on the tipple picking slate. That was bindering the coal, separating the coal.

You see this little boy that what I was telling you about a while ago wasn’t big enough to carry a bucket. There he is right there. There’s his horse. See, probably that’s a family.

They went in there and loaded the coal and pulled it out and dumped it and car [?] back in there. There was a lot of them in the mines around here.

Factory Train

See I can remember when they had a factory train coming through Osage any time of the day. It came from Pennsylvania to Jimtown, then from Jimtown they could catch a train anywhere. East or West, North or South anywhere they wanted to go. They could catch a train.

The only transportation you had was you had to walk from here to Jimtown, hit the train, go to Morgantown, catch the train coming back. They run about every hour or so. Then there was a lot of car hopping too because that freight train ran all the time up in the hollow and Jimtown. I would jump on it and take a ride to Jimtown and wait and ride it back.

Coal Camp

[You grew up in Coal Camp. What was that like? ]

Well, a lot different than what it is today because everybody knew everybody and if something went wrong in the camp, everybody was there to help you. I can remember when somebody had a baby or something, everybody come up there with chicken. People were more friendly, you know what I mean? They were closer together.

Coal camp is like a big city. It’s got everything coal.

A Burnside stove is a favorite. You’d put that in one room and it would heat the whole house. About four room houses about all they had. Coal stove, yeah. You lived in the coal camp they had a team of washers and a wagon and a guy with all that. If we needed coal, he would go get it and bring it up to your house. Wouldn’t charge a penny for it. I can remember them days real good. You ever see that picture in that museum down there about Liberty? If you ever go down, look at that picture. Liberty’s a little town down there.

Busting and Yellow Dogs

When they started breaking the union, see they throwed the people they call scabs -- we call them scabs -- they took their furniture and throwed it out. And them people, their streets was all full of furniture. [The companies] owned everything.

Now I can remember up here at Osage in Chaplin. Osage had a coal mine there, and Chaplin did on the side of the road. That’s all the water there was. You couldn’t even tell when it was dark here because they had so damn many floodlights shining back and forth, you couldn’t even tell when it was dark. And nobody, let’s see they had a lot of guards. But the trouble didn’t start till they started fooling around with [company guards].

And then that’s when the trouble started, that’s when the trouble started. It was knowed all over the place. It was knowed all over the country.

We use to call [the company guards] yellow dogs. They carried guns and they thought they owned everything. They found out different.

Them old union men that we had are now gone. Yeah they’re all dead. I’m the only one around here. I’m the only one around here knows this stuff. And I try to tell them.

Shifts

[They ran] three shifts. One day shift, afternoon and night. See here, this is Uncle Lloyd right there [refers to photo]. That’s me when I was a kid. All these people are dead here. All of them. Let’s see. This guy lives up in Granville. All these guys here I was raised with in Granville. They’re all gone Second shift. 1940 picture was taken. It shows up good don’t it? Most of them was from around here, not too far. Around Granville, well Granville that’s where the tipple was at. Star City, Evansdale, Brier Hill, just right around here.

This here’s beginning of a shift there everybody’s waiting to go in. You know in them days you had to walk every place. There’s no trips, no nothing. Then in 1945 or something they started bringing loading machines.

There use to be a mine here called Hell Creek brought them in earlier than that. That’s when we were working seven hours a day then, too.

After a shift when we got ready to come home, they’d side-track us or something to bring a load of coal out. That’s when we struck. We got paid for the time we went in till the time we went out. No trouble getting you in there, but getting you out.

River Ferry from Star City and Brier Hill

I can remember a lot of people here worked there from Star City and Brier Hill. They went together and bought themselves a room so they wouldn’t have to pay a nickel to ride the ferry. That ferry, they had a ferry down there you know. High water, low water or not, they’d do it. They’d load that boat on high water up the river a long ways then they’d start across by the time they’d got across they’d be close to the tipple.

Just think. There was everything floating in that river when it was high. Logs, trees and everything. And the river wasn’t very deep then because they didn’t have the locks. The only locks they had was up here. Cause in 1932 I can remember whenever it went dry.

Seasonal Work

We’d set down there on the company store on the porch down there, and then that girl would call us up whether or not we worked tomorrow. If she said there was no work, we’d take off and go off somewheres. Sat around all damn day just to hear whether we worked or not.

Interview with former Scott's Run miner Lewis Loretta by Kirk Hazen, in Scott's Run Voices, from Scott's Run Writing Heritage Project, West Virginia History, Volume 53, 1994

Striking miners, Scott's Run, West Virginia: photo by Ben Shahn, October 1935 (Farm Security Administration Collection, Library of Congress)

Pursglove Mine, Scott's Run, West Virginia: photo by Ben Shahn, October 1935 (Farm Security Administration Collection, Library of Congress)

Sunday in Scott's Run, West Virginia: photo by Ben Shahn, October 1935 (Farm Security Administration Collection, Library of Congress)

![[Untitled photo, possibly related to: Sunday in Scotts Run, West Virginia]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/proxy/AVvXsEgux3nYhyLc1X24WRNYPSg9V2fWy3m9T-FBbaiJBkZRc0Fp9Aw8F826kFxukRlKqInMgGQQEiElWP1-3vAuAVuyE1otLnK90n0pD8unUsxLRiElKC2ue91DRX-KIwFUS-HLFNLTm7_U86kNjkOOx324hYj8h0MG6mW4xZoQ5FHsNrIv=s0-d-e1-ft)

Sunday in Scott's Run, West Virginia: photo by Ben Shahn, October 1935 (Farm Security Administration Collection, Library of Congress)

Sunday in Scott's Run, West Virginia: photo by Ben Shahn, October 1935 (Farm Security Administration Collection, Library of Congress)

Scott's Run, West Virginia. Negro family living in Moose Hall: photo by Ben Shahn, October 1935 (Farm Security Administration Collection, Library of Congress)

Scott's Run, West Virginia. Negro family living in Moose Hall: photo by Ben Shahn, October 1935 (Farm Security Administration Collection, Library of Congress)

Liberty, unincorporated, Scott's Run, West Virginia: photo by Ben Shahn, October 1935 (Farm Security Administration Collection, Library of Congress)

"Black Fury" poster, a movie about a strike. Scott's Run, West Virginia: photo by Ben Shahn, October 1935 (Farm Security Administration Collection, Library of Congress)

"Black Fury" a movie about a strike. Scott's Run, West Virginia: photo by Ben Shahn, October 1935 (Farm Security Administration Collection, Library of Congress)

Payoff at Pursglove Mine, Scott's Run, West Virginia: photo by Ben Shahn, October 1935 (Farm Security Administration Collection, Library of Congress)

![[Untitled photo, possibly related to: Scotts Run, West Virginia, walking into town for relief food]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/proxy/AVvXsEgaVqzcXfYzwyBwU7naMs-J4McD5_rSABOn7aOIIO0QNzC1Mg-i4bJClpDrcPN64w6RXfK2DMr8lyl0qc4IVagFp1Ick8tOeeqBnTNttmHDCxvXr5hyphenhyphenyq-818X3xT7Fia_kY2jMdLJ2P6yeZo9PpptXDd8XhuJAxn46cHT-bHIdJPuA=s0-d-e1-ft)

Walking into town for food relief, Scott's Run, West Virginia: photo by Ben Shahn, October 1935 (Farm Security Administration Collection, Library of Congress)

Relief check, Scott's Run, West Virginia: photo by Ben Shahn, October 1935 (Farm Security Administration Collection, Library of Congress)

![[Untitled photo, possibly related to: Relief check, Scotts Run, West Virginia]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/proxy/AVvXsEjzU971JusyvDh1CtiNL7PH9dVmdADImhj8mcyaaYPTc37ZdVBFSQKY249tzXGzE5SBk04r_d6AMX_hbSR3oEaPAKsmHFW5_hL3HIdHnrOwg_CADE5UhyKhTJvWK4gW_7x6jDg-zp-zy95v1m9_QULBSron94_hJrdiIzxB9fknjWQz=s0-d-e1-ft)

Relief check, Scott's Run, West Virginia: photo by Ben Shahn, October 1935 (Farm Security Administration Collection, Library of Congress)

Waiting for relief check, Scott's Run, West Virginia: photo by Ben Shahn, October 1935 (Farm Security Administration Collection, Library of Congress)

Inhabitant of Scott's Run, West Virginia who has just received a relief check: photo by Ben Shahn, October 1935 (Farm Security Administration Collection, Library of Congress)

![[Untitled photo, possibly related to: House stained by coal dust, Pursglove Mine, Scotts Run, West Virginia]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/proxy/AVvXsEijfgkYdMoyPudkA0WwZuYzmA9A9lwBgw_f7Qg5nFqedmk_pXhDKRwzdWT0DM5OEFosnJPu6uQ06AM4O83zKVrzzjTClCOJr4zAn4tk3XW26kwXKsQvAmn88XvUVRZf1Hi8Mo6NxFjKqam9gUn-WhnKaXVrgRWu9Wjmd0O45hn678nU=s0-d-e1-ft)

Houses stained by coal dust, Pursglove Mine, Scott's Run, West Virginia: photo by Ben Shahn, October 1935 (Farm Security Administration Collection, Library of Congress)

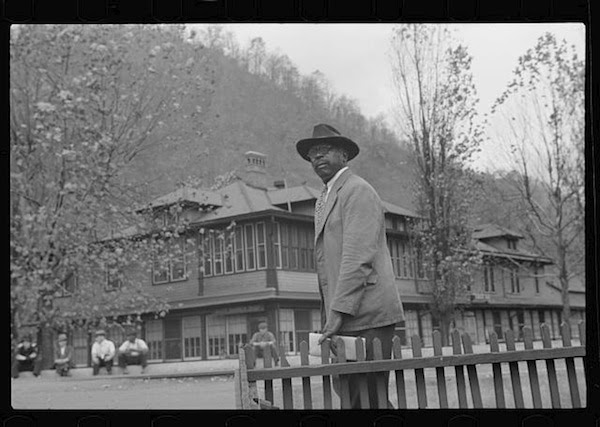

Men in Sunday clothes with miners’ clubhouse in the background. Omar, Scott's Run, West Virginia: photo by Ben Shahn. October 1935 (Farm Security Administration Collection, Library of Congress)

Doped singer, "Love oh, love, oh keerless love": Scott's Run, West Virginia. Relief investigator noted a number of dope cases: photo by Ben Shahn, October 1935 (Farm Security Administration Collection, Library of Congress)

![[Untitled photo, possibly related to: Doped singer, "Love oh, love, oh keerless love," Scotts Run, West Virginia. Relief investigator reported a number of dope cases at Scotts Run]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/proxy/AVvXsEi7MVdS-51Y-AlNsNfTkhry6rEBNysbhSU-QknBoanRIlMQ5FxWLUaJTjqzI_HatjS1CVSW-BOjRs894WgQo2n7C9k1CqCSoyKQ48Ce5-CoSjl5Jlh_hZm9phT1xyefqKgTA8I0oqRYWDSy2hTF42UkaCjX9cbw9RFN0Grqt3oDgb84=s0-d-e1-ft)

Scott's Run, West Virginia: photo by Ben Shahn, October 1935 (Farm Security Administration Collection, Library of Congress)

![[Untitled photo, possibly related to: Doped singer, "Love oh, love, oh keerless love," Scotts Run, West Virginia. Relief investigator reported a number of dope cases at Scotts Run]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/proxy/AVvXsEg1GKmZ7H6pFsM4Ass6BLnaPkuautudWgX2Yh9h9xdqFV1CG27-8-jDRVvDy853zrejF0QT3l9F7F1Q0xra9rLtS9fVXKQsR_WlN_tU6lROCziNRx-PMSxo0enYzotZrNHNZfaQhpJRnBdotq_5vH3GM4AtcLW2JVMI7GmxJ3PmWh8w=s0-d-e1-ft)

Scott's Run, West Virginia: photo by Ben Shahn, October 1935 (Farm Security Administration Collection, Library of Congress)

![[Untitled photo, possibly related to: Doped singer, "Love oh, love, oh keerless love," Scotts Run, West Virginia. Relief investigator reported a number of dope cases at Scotts Run]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/proxy/AVvXsEgGuCLRnWZYP5lb7wUV5WDZ5PLLxdE-n3RmAUT-sj79LClSXaMT2fL9Zo8EGYbuoSsy-WOJqI8uEIYvYVmtHzi_v7zPWqfL37CGZXxlMR_jDfykx5czluIKOoRE_-HlbMQ7grh7T9hDC3rxdWlJUVmNul5IU1nD9JFrG-owDufxhgGD=s0-d-e1-ft)

Scott's Run, West Virginia: photo by Ben Shahn, October 1935 (Farm Security Administration Collection, Library of Congress)

![[Untitled photo, possibly related to: Scotts Run, West Virginia. Miner's sons]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/proxy/AVvXsEjBvdpvq4E0vvbsZgBFCTpGHYfWxhgGu63Dyma_r_NWJn0A06-OVArRcETIyZDnFMc9g5R1lBlzzntX28m1Zsi5fpg1J8pVQSzUYixxQYTYzO-_I9_JoZXxBIBVKVJcWnoo2WoTPJcAS65z0NyCgZ_Orwh0q7t9Vxmb13D1wOGhwoxx=s0-d-e1-ft)

Miner's sons, Scott's Run, West Virginia: photo by Ben Shahn, October 1935 (Farm Security Administration Collection, Library of Congress)

Miner's sons, Scott's Run, West Virginia: photo by Ben Shahn, October 1935 (Farm Security Administration Collection, Library of Congress)

Miners' houses, Scott's Run, West Virginia. Note sewerage system: photo by Elmer Johnson, 1935 (Farm Security Administration Collection, Library of Congress)

Scott's Run mining camps, near Morgantown, West Virginia: photo by Walker Evans, July 1935 (Farm Security Administration Collection, Library of Congress)

Scott's Run mining camps, near Morgantown, West Virginia. Company houses: photo by Walker Evans, July 1935 (Farm Security Administration Collection, Library of Congress)

Women selling ice cream and cake, Scott's Run, West Virginia: photo by Walker Evans, July 1935 (Farm Security Administration Collection, Library of Congress)

Scott's Run, West Virginia: photo by Walker Evans, July 1935 (Farm Security Administration Collection, Library of Congress)

Mexican miner and child, Bertha Hill, Scott's Run, West Virginia: photo by Marion Post Wolcott, September 1938 (Farm Security Administration Collection, Library of Congress)

Mexican miner and child, Bertha Hill, Scott's Run, West Virginia: photo by Marion Post Wolcott, September 1938 (Farm Security Administration Collection, Library of Congress)

![[Untitled photo, possibly related to: Mexican miner and child, Bertha Hill, West Virginia. Many Mexicans and Negroes were brought into Scotts Run around 1926 to break the strike. Now about one fourth of all mines employ any at all and these, only very small percent and "only the cream." They are generally accepted by other folks and there is a good deal of mixing and intermarrying]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/proxy/AVvXsEhU4sRnTNTEZ4X5icQIz2E1i7VKxoXoUzrYOi3q2EWHtUy7-HXqq2BEo4bvmgJk2H8o6KGC8kCRpfcpUEA0zMtzgPwpWCSAKohPd2MgzFTeD6uhxrwpA2h-qoGDkrBYKmUd8VtStkV_18ZgHE8AzIsiJJom0wQhS7VtqUwGShQ8T5im=s0-d-e1-ft)

Mexican miner and child, Bertha Hill, Scott's Run, West Virginia. Many Mexicans and Negroes were brought into Scott's Run around 1926 to break the strike. Now about one-fourth of all mines employ any at all of these, only very small percent and "only the cream". They are generally accepted by other folks and there is a good deal of mixing and intermarrying: photo by Marion Post Wolcott, September 1938 (Farm Security Administration Collection, Library of Congress)

![[Untitled photo, possibly related to: Coal miner's child, Omar, West Virginia]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/proxy/AVvXsEiC27ISNgk5vg1Y9LfomBbv_RLxXiqZGug99-Vwhy3Na5mSAIV5Mn6eG8QXYnVrwCNe79xNxRqFLBARYOf2yUFRs6zDF9MwDJTLCYvpNk514jMG3nYsOAsnB1LlWTjhyn6e8UbBv5LOYAHR8yimjCGVUvH1-CoXw0EkWQFnpioxUMo6=s0-d-e1-ft)

miner's children, Omar, Scott's Run, West Virginia: photo by Marion Post Wolcott, September 1938 (Farm Security Administration Collection, Library of Congress)

Coal miner's son, Omar, Scott's Run, West Virginia: photo by Marion Post Wolcott, September 1938 (Farm Security Administration Collection, Library of Congress)

Old fences around farm in coal mining section near Scott's Run, West Virginia: photo by Marion Post Wolcott, September 1938 (Farm Security Administration Collection, Library of Congress)

Old bridge, Scott's Run, West Virginia: photo by Marion Post Wolcott, September 1938 (Farm Security Administration Collection, Library of Congress)

Coal barge on river, Scott's Run, West Virginia: photo by Marion Post Wolcott, September 1938 (Farm Security Administration Collection, Library of Congress)

Coal on riverboat, Scott's Run, West Virginia: photo by Marion Post Wolcott, September 1938 (Farm Security Administration Collection, Library of Congress)

Wood pile for use in mine and coal cars, Scott's Run, West Virginia:

photo by Marion Post Wolcott, September 1938 (Farm Security Administration Collection, Library of Congress)

Burning slag near coal mine, Scott's Run, West Virginia:

photo by Marion Post Wolcott, September 1938 (Farm Security Administration Collection, Library of Congress)

Coal miner waiting for the next shift, Bertha Hill, Scott's Run, West Virginia:

photo by Marion Post Wolcott, September 1938 (Farm Security Administration Collection, Library of Congress)

Coal miner, Chaplin Collieries, Scott's Run, West Virginia: photo by Marion Post Wolcott, September 1938 (Farm Security Administration Collection, Library of Congress)

Miner (Russian). Capels, West Virginia. Marion Post Wolcott. September 1938 (Farm Security Administration Collection, Library of Congress)

Company houses, coal mining section, Pursglove, Scott's Run, West Virginia:

photo by Marion Post Wolcott, September 1938 (Farm Security Administration Collection, Library of Congress)

Company houses, coal mining section, Pursglove, Scott's Run, West Virginia:

photo by Marion Post Wolcott, September 1938 (Farm Security Administration Collection, Library of Congress)

Main store front in coal mining town, Scott's Run, West Virginia:

photo by Marion Post Wolcott, September 1938 (Farm Security Administration Collection, Library of Congress)

Osage, on Scott's Run, West Virginia. Drugstore window display in mining town:

photo by Marion Post Wolcott, September 1938 (Farm Security Administration Collection, Library of Congress)

Storefront, coal mining camp, Scott's Run, West Virginia:

photo by Marion Post Wolcott, September 1938 (Farm Security Administration Collection, Library of Congress)

Union barber shop in mining town, Scott's Run, West Virginia:

photo by Marion Post Wolcott, September 1938 (Farm Security Administration Collection, Library of Congress)

Mine workers' club, beer and dance hall, Scott's Run, West Virginia:

photo by Marion Post Wolcott, September 1938 (Farm Security Administration Collection, Library of Congress)

Coal miners on steps of company store, Scott's Run, West Virginia:

photo by Marion Post Wolcott, September 1938 (Farm Security Administration Collection, Library of Congress)

Coal miners buying supplies in company store, Scott's Run, West Virginia:

photo by Marion Post Wolcott, September 1938 (Farm Security Administration Collection, Library of Congress)

Former coal miner, worked twelve years for Chaplin Coal Company as

hand coal loader. He and several others complained to company about

conditions not being up to NRA (National Recovery Administration)

standards. All lost jobs. He's now on WPA (Works Progress

Administration) at thirty-eight dollars and twenty-five cents per month.

Scott's Run, West Virginia:

photo by Marion Post Wolcott, September 1938 (Farm Security Administration Collection, Library of Congress)

Unemployed miner's home he built. "It'll be purtier when I paint it." Osage, Scott's Run, West Virginia: photo by Marion Post Wolcott, September 1938 (Farm Security Administration Collection, Library of Congress)

Unemployed miner's home he built. "It'll be purtier when I paint it." Osage, Scott's Run, West Virginia: photo by Marion Post Wolcott, September 1938 (Farm Security Administration Collection, Library of Congress)

Carrying water, coal miners' shacks, Scott's Run, West Virginia:

photo by Marion Post Wolcott, September 1938 (Farm Security Administration Collection, Library of Congress)

Shanties by the river. Coal miners' shacks, Scott's Run, West Virginia:

photo by Marion Post Wolcott, September 1938 (Farm Security Administration Collection, Library of Congress)

Former miners (note crutches). Scott's Run, West Virginia:

photo by Marion Post Wolcott, September 1938 (Farm Security Administration Collection, Library of Congress)

Bohemian coal miners, now unemployed, since mechanization of the mines, Jere, Scott's Run, West Virginia:

photo by Marion Post Wolcott, September 1938 (Farm Security Administration Collection, Library of Congress)

Woman

(probably Hungarian) coming home along railroad tracks in coal mining

town, company houses at right, Pursglove, Scott's Run, West Virginia:

photo by Marion Post Wolcott, September 1938 (Farm Security Administration Collection, Library of Congress)

Old man, Hungarian, with cane, going home after work along tracks, Pursglove, Scott's Run, West Virginia:

photo by Marion Post Wolcott, September 1938 (Farm Security Administration Collection, Library of Congress)

Even the cow goes home along the tracks, the main thoroughfare. Scott's Run, West Virginia:

photo by Marion Post Wolcott, September 1938 (Farm Security Administration Collection, Library of Congress)

Even the cow goes home along the tracks, the main thoroughfare. Scott's Run, West Virginia:

photo by Marion Post Wolcott, September 1938 (Farm Security Administration Collection, Library of Congress)

Old rotting coal tipple, Scott's Run, West Virginia:

photo by Marion Post Wolcott, September 1938 (Farm Security Administration Collection, Library of Congress)

Children playing around old coal tipple, Scott's Run, West Virginia:

photo by Marion Post Wolcott, September 1938 (Farm Security Administration Collection, Library of Congress)

Abandoned coal tipple, Scott's Run, West Virginia:

photo by Marion Post Wolcott, September 1938 (Farm Security Administration Collection, Library of Congress)

"White" school house, Scott's Run, West Virginia:

photo by Marion Post Wolcott, September 1938 (Farm Security Administration Collection, Library of Congress)

Negro school, Scott's Run, West Virginia:

photo by Marion Post Wolcott, September 1938 (Farm Security Administration Collection, Library of Congress)

Coal miner's wife getting water from pump, company houses, Pursglove, Scott's Run, West Virginia:

photo by Marion Post Wolcott, September 1938 (Farm Security Administration Collection, Library of Congress)

Clothes line on fence in front yard of miner's home, Scott's Run, West Virginia: photo by Marion Post Wolcott, September 1938 ( (Farm Security Administration Collection, Library of Congress)

Wives of coal miners talking over the fence. Capels, West Virginia. Marion Post Wolcott. September 1938

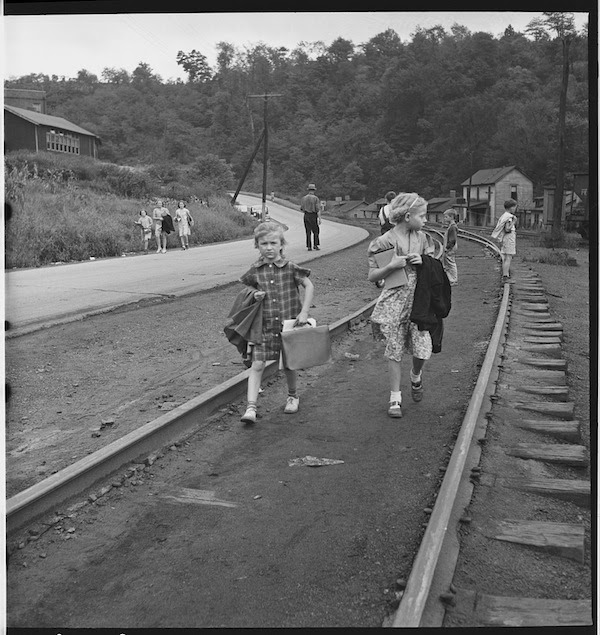

Coming home from school. Mining town. Osage, Scotts Run, West Virginia. Marion Post Wolcott. September 1938

Coal miner’s child taking home kerosene for lamps. Company houses and

a coal tipple are in the background in Scott's Run, near Morgantown:

photo by Marion Post Wolcott, September 1938 (Farm Security Administration Collection, Library of Congress)

Watching a football game, Star City, West Virginia: photo by Ben Shahn, 1935 (Farm Security Administration Collection, Library of Congress)

Omar, mining town, West Virginia: photo by Ben Shahn, October 1935 (Farm Security Administration Collection, Library of Congress)

Pay day. Coal mining town, Omar, West Virginia:

photo by Marion Post Wolcott, September 1938 (Farm Security Administration Collection, Library of Congress)

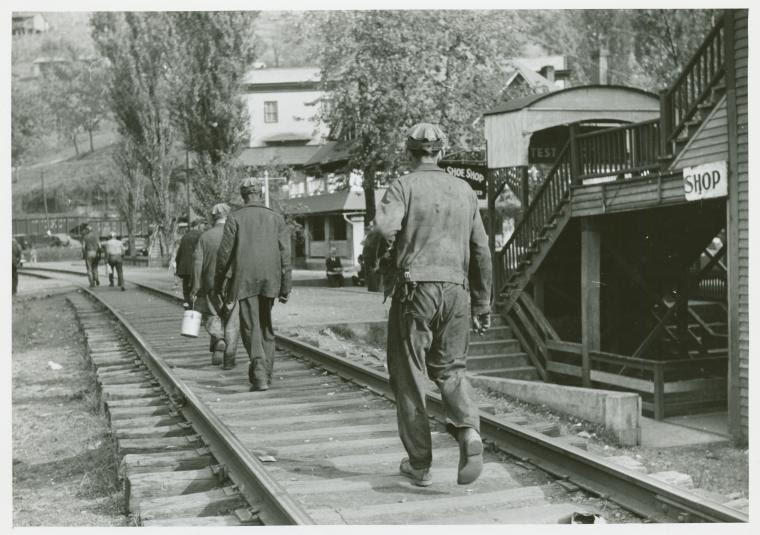

Coal miners going home from work, Omar, West Virginia:

photo by Marion Post Wolcott, September 1938 (Farm Security Administration Collection, Library of Congress)

Negro school children, Omar, West Virginia:

photo by Marion Post Wolcott, September 1938 (Farm Security Administration Collection, Library of Congress)

Coal miner's family. Pursglove, West Virginia: photo by Marion Post Wolcott, September 1938 (Farm Security Administration Collection, Library of Congress)

Coal miners' card game on the porch, Chaplin, West Virginia: photo by Marion Post Wolcott, September 1938 (Farm Security Administration Collection, Library of Congress)

Coal miner's wife carrying home water from the hill, Bertha Hill, West Virginia: photo by Marion Post Wolcott, September 1938 (Farm Security Administration Collection, Library of Congress)

Mexican miner's wife, Scotts Run, Bertha Hill, West Virginia: photo by Marion Post Wolcott, September 1938 (Farm Security Administration Collection, Library of Congress)

Child of coal miner, Jere, Scott's Run, West Virginia: photo by Marion Post Wolcott, September 1938 (Farm Security Administration Collection, Library of Congress)

Miner's wife on porch of their home, an abandoned company store. Pursglove, West Virginia: photo by Marion Post Wolcott, September 1938 (Farm Security Administration Collection, Library of Congress)

Water

But during those times it was you know and we had to carry water. I first remember that we had to go to the well and carry water. Because we didn’t always have water in our houses, you know. Then when the coal mining, the coal company [came], they put up an old fashioned pump.

The hand pumps. Yeah . . . about every six houses, they put a pump. So we still had to carry water. I remember buckets of water we had to carry especially on wash days.

Monday: Wash Day and Bread Day

Monday was wash day and bread day. My Momma made bread. She’d make bread that would last the whole week. We’d wash clothes and bake. And I remember we’d come home from school and had to finish the washing cause we didn’t always have washing machines. We had the oppression [?] -- the rub board.

I thank God for my raising. It has made me appreciate life so much. I can really appreciate things you know now because I knew the hard time. But everybody did their washing like that, you’d see a line clothes line because everybody had to put your clothes outside because you didn’t have a dryer.

So you’d walk down the community and this row of houses and almost everybody washed Monday and you’d see just lines and lines of clothes and things were pretty and white. I remember the clothes were so white the sun would sparkle on them, you know, cause you’d wash twice and rinsed twice.

All day, you was washing all day, and we came from school. Because what my mom didn’t do, we got a chance to do. I remember when my dad bought our washing machine he said, “My God she’d about wash herself to death.” Because we finally got a washer. Everyday the washing machine was up until we got use to it.

Pursglove #2

Pursglove number two that’s where we lived. Pursglove two and over on the other hill was Pursglove number eight. They was all owned by the same man, but the little community like a little nest of houses maybe about fifty families. Maybe a little bit more than that, maybe a little less. But that was called Pursglove number two and then over on the other hill there was one called Pursglove number eight. And they had their own little school building and their own little church and that’s how it was.

Soup Lines and the WPA

I remember vaguely the soup lines right here in Osage. I remember when the WPA was first started and I must’ve been about eight years old maybe when all that started WPA then they had just a soup line. A place in Osage made big meals and you just stand in line and went and got the food. You had a hot lunch.

Quakers

I remember, and this was when I was in grade school, maybe second, third, fourth grade. But I remember the Quakers came here. There’s a building up the road about two miles called the Shack, have you heard anything about the Shack?

There was a shack and they came together and sponsored a hot lunch program for the kids from all the schools. Okay all the schools in these communities like Pursglove, over Pursglove number eight whatever. The Quakers did that -- they sponsored a hot lunch program and the moms would come and cook everyday and so the kids everyday at lunch time we had a good hot meal, a good hot lunch.

They had certain days each mom cooked, certain days have three or four moms cook Monday, three or four moms cooked Tuesday. I remember those meals were good. We always had fruit and sometimes you didn’t get fruit at home you know, but they always had fruit. Always gave you a real nourishing meal, a hot bowl of soup and some crackers or peanut butter on nice brown thick bread and jelly.

Everyday Life

My brother-in-law had a car and we just thought it was just great if we could just ride from Pursglove to Osage. That was just the greatest cause we walked everywhere. Bus fare was just about a nickel, I think. I remember candy bars were two cents. We use to sell pop bottles to get money to buy some pop, you know, candy, something sweet that we craved.

But relations were real good. Everybody knew everybody. And if anybody got sick, people call midwives. I didn’t call them that -- just mothers that knew anything if anybody got sick, like pneumonia or something, they knew what to conjure up. All kinds of saps and oils.

Home Remedies

Yeah, I wish I remember that stuff that my mom knew because you didn’t go to doctor all the time. First off you couldn’t afford it, and then they had one company doctor. One thing, the coal mines would provide a doctor for all, and so you needed the doctor when he was somewhere else. Mrs. Williams needed him, or the boys needed a doctor? Well he was over at Pursglove number eight so you couldn’t always get a doctor and so, but they knew what to use. You had whooping cough with pneumonia or whatever and it worked. And all kinds of teas and roots and herbs.

We kept stuff all the time. My mother kept sassafras tea and she kept all kind of roots. I can’t remember all the stuff that she did have. And when you got something, she just knew what to make. And I remember she made homemade cough syrup. This was good, now. She would take a whole lemon and cut it up the peel and all, and she would take onions and cut that up in there, and then she would take honey if she could -- or even sugar, and put that in the oven and let that bake, and it came a real thick syrup. And that’s what she gave you for cough. That lemon did it and that onion. It didn’t taste very good, but it did the job.

Osage and the Company Store

Osage, my goodness, it was a business town -- had two department stores, I think. I forget how many. We had an A and P here and I don’t know how many grocery stores and a company store. Let me tell you what a company store is.

Okay. A company store, it’s owned by the man who owned the coal mines. Okay. They would have a great big store and they had almost everything in the store and what they didn’t have in the store you could get. Then what they did, like you go to the company store, okay, just like you go to a market and shop, that’s what they had, but you had credit from the company. So my dad never had any money and I’ll tell you why: because our store bill was always bigger than the money that he made, so he was always in the hole as they use to call it. There was a lot of families like that, you know. Your store bill was more than you worked cause there was a big family of us. Everybody wasn’t like that. Some people just didn’t use the company store at all. They just went to stores in Osage. Oh yes, you could, but not till we got old and began to get after-school jobs and things, and we could, you know, help out.

Family

There was nine of us in the house, seven kids and dad and mom made nine of us and we lived in a four-room house. All the houses were four rooms. And you made and you just lived good. I don’t know how you did it. Now we couldn’t do it. I’m telling you I look back now and wonder, but we had two bedrooms upstairs and one for the boys and one for the girls cause you had two big beds in every room. And everybody had the same thing. You had two big beds and girls slept over here some at the top, some at the bottom -- you put two up to the top and two down to the bottom. Think about that, but it was fun. It was fun, it really was, and we had a little heater in our room. You had little coal stoves everywhere and you kept the room warm.

After we got bigger where we could get real jobs and my brothers carried the newspapers, we was able to help out at home and you really didn’t mind doing that because you saw the sacrifice that mom and dad made for you. We bought linoleums and I bought my mom a rocking chair and my sister bought my mother a rocking chair. She always wanted one. Like I said, we got linoleums on the floors and curtains and pretty bedspreads. After we got bigger and then my dad began to have some money, you know, we went to school. I had one sister that went to college. We went away. I went to Washington to work and so the family dribbled down to just two, my baby brother and baby sister, so then there was money.

Swimming

And oh my goodness. . . . I remember the swimming pool, when you first got the swimming pool in the area. The coal miners got together and had a swimming pool made, built up at the Shack. Oh it was fun. We didn’t have a swimming pool cause you could go to the river, you know. When the kids wanted to swim, they’d go to the river to swim because we didn’t have anywhere to swim, but when the coal miners got together and had a swimming pool built (it’s up at the Shack and it’s still there the swimming pool is) that’s when we got a chance to go to the swimming pool.

Or you could find a little creek and dam it up and swim in that, but that was muddy water and you didn’t know what was in it, you know. Oh God, I remember my brother-in-law threw me in one time, one of these muddy rivers, muddy ponds, just stopped it up, and it scared me to death, I tell you what, cause you don’t know what’s in mud. You don’t know whether you ‘re going to run into snakes or whatever. But you know, I didn’t get in there no more. I said. "I’ll never do that again!"

Interview with anonymous former Scott's Run mining community resident by Kirk Hazen, in Scott's Run Voices, from Scott's Run Writing Heritage Project. West Virginia History, Volume 53, 1994

Scott's Run, West Virginia. Outdoor privy. Scene taken from the main highway. The stream is Scott's Run. This privy is typical of many improvised outdoor toilets on Scott's Run. It is made from an old automobile; the house at left is also improvised by the family who occupy it. A stream of water flows past the privy into Scott's Run: photo by Lewis Wickes Hine, March 1937 (US National Archives)

Scott's Run, West Virginia. The Shack Community Center. Scene is typical of crowded space. In center of valley the stream is Scott's Run Creek. The Shack is a community center sponsored by a religious organization: photo by Lewis Wickes Hine, March 1937 (US National Archives)

Scott's Run, West Virginia. Woman gathering coal from mine refuse: photo by Lewis Wickes Hine, March 1937 (US National Archives)

Scott's Run, West Virginia. Pursglove No. 5. Scene taken from main

highway shows typical hillside camp. The houses are multiple

dwellings: photo by Lewis Wickes Hine, March 1937 (US National Archives)

Scott's Run, West Virginia. The Patch. One of the worst camps in Scott's Run. The stream is an auxiliary branch that flows into Scott's Run. The main valley of Scott's Run can be seen towards the right of this picture. These houses were originally built as single bachelor apartments; there are from six to eight separate housekeeping units in the buildings. Many of them are now occupied by families living in one room: photo by Lewis Wickes Hine, March 1937 (US National Archives)

x Scott's Run, West Virginia. The Patch. One of the worst camps in

Scott's Run. The stream is an auxiliary branch that flows into Scott's

Run can be seen towards the right of this picture. These houses were

originally built as single bachelor apartments; there are from six to

eight separate housekeeping units in the buildings. Many of them are

now occupied by families living in one room: photo by Lewis Wickes Hine, March 1937 (US National Archives)

Scott's Run, West Virginia. Jere, mine tipple. Mine bankrupt and closed since December 1936. The camp of this mine is considered a stranded community: photo by Lewis Wickes Hine, March 1937 (US National Archives)

Scott's Run, West Virginia. Troop Hill -- an abandoned coal camp on Scott's Run, West Virginia, December 22, 1936. Mine closed early in 1936. Scene taken from main highway entering Scott's Run, March 1937: photo by Lewis Wickes Hine, March 1937 (US National Archives)

Scott's Run, West Virginia. The Patch. One of the worst camps in Scott's Run. The stream is an auxiliary branch that flows into Scott's Run. The main valley of Scott's Run can be seen towards the right of this picture. These houses were originally built as single bachelor apartments; there are from six to eight separate housekeeping units in the buildings. Many of them are now occupied by families living in one room: photo by Lewis Wickes Hine, March 1937 (US National Archives)

Scott's Run, West Virginia. Jere, mine tipple. Mine bankrupt and closed since December 1936. The camp of this mine is considered a stranded community: photo by Lewis Wickes Hine, March 1937 (US National Archives)

Scott's Run, West Virginia. Troop Hill -- an abandoned coal camp on Scott's Run, West Virginia, December 22, 1936. Mine closed early in 1936. Scene taken from main highway entering Scott's Run, March 1937: photo by Lewis Wickes Hine, March 1937 (US National Archives)

Scott's Run, West Virginia. Chaplin Hill. This scene is typical of

many camps built near the mine. In the background can be seen several

of the government sanitary privies. These houses are multiple

dwellings which accommodate several families. It is one of the few

camps on Scott's Run which affords space for hogs and garden: photo by Lewis Wickes Hine, 1936 (US National Archives)

Scott's Run, West Virginia. Chaplin Hill Mine Tipple. This mine as bankrupt and closed during the summer of 1936. The company was reorganized and began to operate under new management in November 1936: photo by Lewis Wickes Hine, 1936 (US National Archives)

Scott's Run, West Virginia. Cassville, mine tipple. This mine is operating and supplies work for three separate camps (Cassville, New Hill, and the Patch). To the left of picture is shown one of the government privies built by WPA workers in a sanitation campaign organized to eliminate the old typical filthy mine camp toilets: photo by Lewis Wickes Hine, March 1937 (US National Archives)

Scott's Run, West Virginia. Chaplin Hill Mine Tipple. This mine as bankrupt and closed during the summer of 1936. The company was reorganized and began to operate under new management in November 1936: photo by Lewis Wickes Hine, 1936 (US National Archives)

Scott's Run, West Virginia. Cassville, mine tipple. This mine is operating and supplies work for three separate camps (Cassville, New Hill, and the Patch). To the left of picture is shown one of the government privies built by WPA workers in a sanitation campaign organized to eliminate the old typical filthy mine camp toilets: photo by Lewis Wickes Hine, March 1937 (US National Archives)

Scott's Run, West Virginia. Pursglove No. 2. Scene taken from main highway shows company store and typical hillside camp: photo by Lewis Wickes Hine, March 1937 (US National Archives

Scott's Run, West Virginia. Pursglove Mines Nos. 4 and 5. Scene taken from main highway shows typical hillside settlements. Houses shown are for supervisory staff. Camp one of the best on Scott's Run: photo by Lewis Wickes Hine, March 1937 (US National Archives)

Scott's Run, West Virginia. Pursglove Mines Nos. 3 and 4. This is

the largest company of Scott's Run. Scene shows main Scott's Run

Highway and atmosphere loaded with coal dust and typical of Scott's

Run on any working day: photo by Lewis Wickes Hine, March 1937 (US National Archives)

Scott's Run, West Virginia. Another view of Pursglove Mines Nos. 3 and 4: photo by Lewis Wickes Hine, March 1937 (US National Archives)

Scott's Run, West Virginia. This building is a part of the abandoned mine buildings of the stranded camp of Jere. It is the exterior of the old fan house. The children are a part of a WPA nursery now functioning in the camp: photo by Lewis Wickes Hine, March 1937 (US National Archives)

9 comments:

Quite extraordinary, Tom. I've spent too many years up to my neck in fancy stuff about the shiftiness of representation - documentary, history, realism, verisimilitude blah blah - but these words and images feel like the plain straight truth of things. No arguing with those faces, that improvised privy, the cow, or the corner you had to get around before you lit the fuse. A whole hard world in every detail. Overwhelming.

TC,

I think the last comment I made at your place will be the same as this: This is why my grandfather, the teacher in town, was forced to leave West Virginia -- leaving my mom and grandmother behind -- and head to Detroit where he slept in the public parks until securing a job at the Briggs factory.

Thanks for the good words, Barry and Kent.

Sometimes there's a rip in the curtain and the circus of representation parts its veils to allow us to see something like reality.

The photographers who took most of these pictures were being paid a standard wage of $5 per day, plus basic-minimal "expenses". Principle appears to have been a common source of persistence in what was often challenging labour.

The miners weren't exactly getting rich either, and their lives were continually at risk, as they did their brutal work, when work was to be had -- certainly not out of principle, unless it be the principle of survival for themselves and their families.

"Surface rights" to the hilly rural lands of this part of West Virginia, above a particularly rich coal seam, shrewdly purchased for a speculative song, gave the coal companies "legal right" to "undermine"; and they undermined, and they undermined... until they were gone, and the coal and large sections of the hillsides exhausted.

It's been interesting to me to see how the same porous hollow has been lit with differing shades of historical meaning, each feeling equally "true", by each of the photographers who ventured there.

Marion Post Wolcott captures a close sense of the human scale, Lewis Hine a larger historical picture, situating the eye within the bleak industrial landscape.

Ben Shahn's photography like his painting has consistently a political motive. It's fascinating to see the uses the former came to serve him in the latter.

Here we seem to have looped back to the theme of representation. People will have noticed how carefully Shahn's Scott's Run painting follows his FSA photo (seen just under the first oral history text).

One curious omission: the figure of the striking miner at left is using a cigarette holder in the photo, but in the painting, the corresponding figure is not. Shahn's attention to detail make that a bit of a puzzler. My guess is that he probably saw the cigarette holder as an affectation, a class-marked if not also gender-marked appurtenance. At the time, cigarette holders were used mostly by women smoking in public. At the House Un-American Activities Committee hearings of 1947 -- as a result of which her husband the novelist and screenwriter Dalton Trumbo, uncooperative with the questioners, would go to prison for eleven months then be blacklisted -- Cleo Fincher Trumbo can be seen using a cigarette holder.

Cleo's health doesn't seem to have been harmed, by the way. She passed away in Los Altos just four years ago, age 93.

I admire her longevity. This post has been five and half years in the making and might well have taken forever, but wanted to wrestle it up here before the flickering carbide lamp goes out.

Thanks for taking the time to put together this extraordinary post--one would have never guessed just how much time one needs for a labor of love like this.

PS. Just a note in passing: "Liberty"--what a misnomer in such a context.

This is an extraordinary, beautiful post, Tom. (We’ve been on the road for some days now, and I’m just catching up, on-line.) The way of life depicted here has changed only in the (mostly) superficial and technical details. The exploitation remains the same. Not just the towns and people die, as a result, but the ecology too.

Many thanks for this one and for the love and care that went into it—a long time coming, as you say. And thanks to the great FSA photographers and Kirk Hazen for preserving some of it.

Posts like these are works of art. This whole blog is a tremendous unfolding work of art, and those take time. This seems a good opportunity to say out loud how much the work and the imagination and the time and the talent that goes in to it all, time after time, is appreciated. Thanks Tom.

Vassilis, it was not just the time but the anachronistic believing in something, perhaps having to do with that howling ironic misnomer.

Coal mining, corporate exploitation of the land, and widespread impoverishment did not vanish from the rural hollows of West Virginia once the Scott's Run holes closed down. Technology ensured there would eventually be both new methods of rapacious violation (think: "mountaintop removal") and fewer jobs.

This was how things looked in coal country in 1974:

Slag (Coal Country, Appalachia)

Two US Presidents have paid attention to West Virginia. The first was FDR, during the 1930s. The second was JFK, who visited West Virginia in the run-up to the 1960 Presidential election. It was an eye-opener for him. He'd never seen that kind of human want in the United States. His bewildered comment: "Imagine... just imagine kids who never drink milk."

He took that sobering experience into the campaign.

"This is a great country, but I think it could be a greater country; and this is a powerful country, but I think it could be a more powerful country... I'm not satisfied when we have over nine billion dollars worth of food - some of it rotting - even though there is a hungry world, and even though four million Americans wait every month for a food package from the government, which averages five cents a day per individual. I saw cases in West Virginia, here in the United States, where children took home part of their school lunch in order to feed their families because I don't think we're meeting our obligations toward these Americans."

John F Kennedy, Presidential Debate vs. Richard Nixon, Chicago, 9 September 1960

"Once he had been sworn in as the President of the United States, Kennedy's first Executive Order was to expand the federal food distribution program for needy families and he had his newly minted Secretary of Agriculture Orville Freeman go down to Welch, WV and hand out the first $95 in food stamps in our nation's history to an unemployed miner trying to support 13 children. And, on the occasion of West Virginia's centennial celebration in the summer of 1963, President Kennedy came back to the state capital in Charleston and, just days before he would give his historic Ich Bin Ein Berliner speech, told the gathered crowd that he saluted and joined the people of West Virginia and would, 'carry on...to Europe the proud realization that not only mountaineers, but also Americans, are always free.'”

Trust Is Not a Word We Use Around Here: Life in Chemical Valley during West Virginia's Water Crisis, Daily Kos, 17 March 2014

Thanks very much, Hazen (your neck of the woods here, Hazen, more or less), and Barry, hadn't seen those good words till just this moment -- and am very happy to have them in this record.

(Things go pretty slowly here now anyway, so I guess the built-in googly comment-lag fits right into the haphazard scheme.)

Very thoughtful of Hazen, who's a veteran hand at folkloric revival himself, to include the transcriber in his list of the people whose faithful documentation makes it possible for us to revisit this history -- and thoughtless of me not to have named her.

The transcriber was Erica Flowers.

And also for the respect, and the record:

Well Known Stranger; Howard Finster's Workout: a film by Hazen Robert Walker and Elizabeth Fine, 1987

Post a Comment