.

Nuclear weapon test Mike (yield 10.4 Mt) on Enewetak Atoll. The test was part of Operation Ivy. Mike was the first hydrogen bomb ever tested, an experimental device not suitable for use as a weapon: photo by Federal Government of the United States, 1 November 1952, 07:14 (National Security Administration Nevada Site Office Photo Library)

Stumbling across street

cane fumble

collapse

What's your problem?

Why can't you just relax

enjoy the sunset

or was it sunrise

the red sun

over the black sea

the apocalypse

if it comes

could it be because

you were brought up

with your cowlicked little

Mick head

cowering under a school desk

in nun supervised rehearsals

Why can't you just relax

enjoy the sunset

or was it sunrise

the red sun

over the black sea

the apocalypse

if it comes

could it be because

you were brought up

with your cowlicked little

Mick head

cowering under a school desk

in nun supervised rehearsals

for the blast

Ivy King: fireball created by King (500 kilotons), very high-yield pure fission bomb, detonated Marshall Islands, November 15, 1952 for US Operation Ivy : photo via U. S. Department of Energy

Solar corona: photo animation by Tomruen, 2005

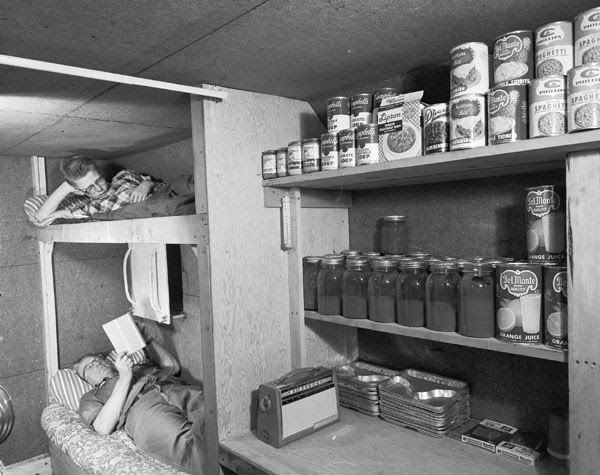

"Fallout shelter built by Louis Severance adjacent to his home near Akron, Michigan includes a special ventilation and escape hatch, an entrance to his basement, tiny kitchen, running water, sanitary facilities, and a sleeping and living area for the family of four. The shelter cost about $1,000. It has a 10-inch reinforced concrete ceiling with thick earth cover and concrete walls. Severance says, 'Ever since I was convinced what damage H-Bombs can do, I've wanted to build the shelter. Just as with my chicken farm, when there's a need I build it.": photographer unknown, c. 1960 (National Archives and Records Administration, Records of the Defense Civil Preparedness Agency

Ivy Mike: fireball created by Mike (10 megatons), first thermonuclear weapon, detonated Marshall Islands, October 31/November 1, 1952 for US Operation Ivy: photo via U. S. Department of Energy

Total war -- Does it not have material and spiritual evil as its consequences?

Hiroshima -- August 6th, 1945: Father John A. Siemes, Professor of Modern Philosophy, Catholic University of Tokyo

Up to August 6th, occasional bombs, which did no great damage, had

fallen on Hiroshima. Many cities roundabout, one after the other, were

destroyed, but Hiroshima itself remained protected. There were almost

daily observation planes over the city but none of them dropped a bomb.

The citizens wondered why they alone had remained undisturbed for so

long a time. There were fantastic rumors that the enemy had something

special in mind for this city, but no one dreamed that the end would

come in such a fashion as on the morning of August 6th.

August 6th began in a bright, clear, summer morning. About seven

o'clock, there was an air raid alarm which we had heard almost every day

and a few planes appeared over the city. No one paid any attention and

at about eight o'clock, the all-clear was sounded. I am sitting in my

room at the Novitiate of the Society of Jesus in Nagatsuke; during the

past half year, the philosophical and theological section of our Mission

had been evacuated to this place from Tokyo. The Novitiate is situated

approximately two kilometers from Hiroshima, half-way up the sides of a

broad valley which stretches from the town at sea level into this

mountainous hinterland, and through which courses a river. From my

window, I have a wonderful view down the valley to the edge of the city.

Suddenly -- the time is approximately 8:14 -- the whole valley is filled

by a garish light which resembles the magnesium light used in

photography, and I am conscious of a wave of heat. I jump to the window

to find out the cause of this remarkable phenomenon, but I see nothing

more than that brilliant yellow light. As I make for the door, it

doesn't occur to me that the light might have something to do with enemy

planes. On the way from the window, I hear a moderately loud explosion

which seems to come from a distance and, at the same time, the windows

are broken in with a loud crash. There has been an interval of perhaps

ten seconds since the flash of light. I am sprayed by fragments of

glass. The entire window frame has been forced into the room. I realize

now that a bomb has burst and I am under the impression that it exploded

directly over our house or in the immediate vicinity.

I am bleeding from cuts about the hands and head. I attempt to get

out of the door. It has been forced outwards by the air pressure and has

become jammed. I force an opening in the door by means of repeated

blows with my hands and feet and come to a broad hallway from which open

the various rooms. Everything is in a state of confusion. All windows

are broken and all the doors are forced inwards. The bookshelves in the

hallway have tumbled down. I do not note a second explosion and the

fliers seem to have gone on. Most of my colleagues have been injured by

fragments of glass. A few are bleeding but none has been seriously

injured. All of us have been fortunate since it is now apparent that the

wall of my room opposite the window has been lacerated by long

fragments of glass.

![[Able Blast]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/proxy/AVvXsEjhqplGzAsPehU01gDVErFV9cX7hzvdD9q4mS2jGSgGaKW_HGVP-JKGbikMomm3Njepekc-6wgHPUP_b9R33yUgIKEoKkxAFgmrYRZtF1U4NjAy2w8soKj-66iN5-Y6JyOgRxHTkhBj=s0-d-e1-ft)

Crossroads ABLE Test. The ABLE test in 1946 was an air drop of the same Fatman-type weapon dropped on Nagasaki.

We proceed to the front of the house to see where the bomb has

landed. There is no evidence, however, of a bomb crater; but the

southeast section of the house is very severely damaged. Not a door nor a

window remains. The blast of air had penetrated the entire house from

the southeast, but the house still stands. It is constructed in a

Japanese style with a wooden framework, but has been greatly

strengthened by the labor of our Brother Gropper as is frequently done

in Japanese homes. Only along the front of the chapel which adjoins the

house, three supports have given way (it has been made in the manner of

Japanese temple, entirely out of wood.)

Down in the valley, perhaps one kilometer toward the city from us,

several peasant homes are on fire and the woods on the opposite side of

the valley are aflame. A few of us go over to help control the flames.

While we are attempting to put things in order, a storm comes up and it

begins to rain. Over the city, clouds of smoke are rising and I hear a

few slight explosions. I come to the conclusion that an incendiary bomb

with an especially strong explosive action has gone off down in the

valley. A few of us saw three planes at great altitude over the city at

the time of the explosion. I, myself, saw no aircraft whatsoever.

Perhaps a half-hour after the explosion, a procession of people

begins to stream up the valley from the city. The crowd thickens

continuously. A few come up the road to our house. We give them first

aid and bring them into the chapel, which we have in the meantime

cleaned and cleared of wreckage, and put them to rest on the straw mats

which constitute the floor of Japanese houses. A few display horrible

wounds of the extremities and back. The small quantity of fat which we

possessed during this time of war was soon used up in the care of the

burns. Father Rektor who, before taking holy orders, had studied

medicine, ministers to the injured, but our bandages and drugs are soon

gone. We must be content with cleansing the wounds.

More and more of the injured come to us. The least injured drag the

more seriously wounded. There are wounded soldiers, and mothers carrying

burned children in their arms. From the houses of the farmers in the

valley comes word: "Our houses are full of wounded and dying. Can you

help, at least by taking the worst cases?" The wounded come from the

sections at the edge of the city. They saw the bright light, their

houses collapsed and buried the inmates in their rooms. Those that were

in the open suffered instantaneous burns, particularly on the lightly

clothed or unclothed parts of the body. Numerous fires sprang up which

soon consumed the entire district. We now conclude that the epicenter of

the explosion was at the edge of the city near the Jokogawa Station,

three kilometers away from us. We are concerned about Father Kopp who

that same morning, went to hold Mass at the Sisters of the Poor, who

have a home for children at the edge of the city. He had not returned as

yet.

![[Baker Blast]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/proxy/AVvXsEip8pNwLQIGzpqWBUsO1kel0YiHYI2tCSaqZeLogGeL4Q3ueeX9Fdq0NfPai-SdwDa0ZNdHtaftrUf8qtxborX9dHodXOGuq_3K7zq22peu9TRzyceFUNhzo3-SX5l15mTzNbEy3J_PvA=s0-d-e1-ft)

Crossroads BAKER Test. The BAKER test in 1946 was a Fatman-type weapon detonated 96 feet below the surface of the ocean.

Toward noon, our large chapel and library are filled with the

seriously injured. The procession of refugees from the city continues.

Finally, about one o'clock, Father Kopp returns, together with the

Sisters. Their house and the entire district where they live has burned

to the ground. Father Kopp is bleeding about the head and neck, and he

has a large burn on the right palm. He was standing in front of the

nunnery ready to go home. All of a sudden, he became aware of the light,

felt the wave of heat and a large blister formed on his hand. The

windows were torn out by the blast. He thought that the bomb had fallen

in his immediate vicinity. The nunnery, also a wooden structure made by

our Brother Gropper, still remained but soon it is noted that the house

is as good as lost because the fire, which had begun at many points in

the neighborhood, sweeps closer and closer, and water is not available.

There is still time to rescue certain things from the house and to bury

them in an open spot. Then the house is swept by flame, and they fight

their way back to us along the shore of the river and through the

burning streets.

Soon comes news that the entire city has been destroyed by the

explosion and that it is on fire. What became of Father Superior and the

three other Fathers who were at the center of the city at the Central

Mission and Parish House? We had up to this time not given them a

thought because we did not believe that the effects of the bomb

encompassed the entire city. Also, we did not want to go into town

except under pressure of dire necessity, because we thought that the

population was greatly perturbed and that it might take revenge on any

foreigners which they might consider spiteful onlookers of their

misfortune, or even spies.

Father Stolte and Father Erlinghagen go down to the road which is

still full of refugees and bring in the seriously injured who have

sunken by the wayside, to the temporary aid station at the village

school. There iodine is applied to the wounds but they are left

uncleansed. Neither ointments nor other therapeutic agents are

available. Those that have been brought in are laid on the floor and no

one can give them any further care. What could one do when all means are

lacking? Under those circumstances, it is almost useless to bring them

in. Among the passersby, there are many who are uninjured. In a

purposeless, insensate manner, distraught by the magnitude of the

disaster most of them rush by and none conceives the thought of

organizing help on his own initiative. They are concerned only with the

welfare of their own families. It became clear to us during these days

that the Japanese displayed little initiative, preparedness, and

organizational skill in preparation for catastrophes. They failed to

carry out any rescue work when something could have been saved by a

cooperative effort, and fatalistically let the catastrophe take its

course. When we urged them to take part in the rescue work, they did

everything willingly, but on their own initiative they did very little.

At about four o'clock in the afternoon, a theology student and two

kindergarten children, who lived at the Parish House and adjoining

buildings which had burned down, came in and said that Father Superior

LaSalle and Father Schiffer had been seriously injured and that they had

taken refuge in Asano Park on the river bank. It is obvious that we

must bring them in since they are too weak to come here on foot.

![[Buster-Jangle Detonation]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/proxy/AVvXsEi8pUmZjsHoqr5dsag94XnQiC9QIP9AOu4GM9CGKx708UwuNFjDBy7PwNQvpC9Hr-PTfa8_SXo00xqL3O3DsynQVBgDTSKWG1dwNLvTc27uFu5PsgUBIQBepqIWNZKPGuKVoTG9SOsK=s0-d-e1-ft)

Buster-Jangle Test. One of the test detonations from the Buster-Jangle series in Nevada.

Hurriedly, we get together two stretchers and seven of us rush toward

the city. Father Rektor comes along with food and medicine. The closer

we get to the city, the greater is the evidence of destruction and the

more difficult it is to make our way. The houses at the edge of the city

are all severely damaged. Many have collapsed or burned down. Further

in, almost all of the dwellings have been damaged by fire. Where the

city stood, there is a gigantic burned-out scar. We make our way along

the street on the river bank among the burning and smoking ruins. Twice

we are forced into the river itself by the heat and smoke at the level

of the street.

Frightfully burned people beckon to us. Along the way, there are many

dead and dying. On the Misasi Bridge, which leads into the inner city

we are met by a long procession of soldiers who have suffered burns.

They drag themselves along with the help of staves or are carried by

their less severely injured comrades...an endless procession of the

unfortunate.

Abandoned on the bridge, there stand with sunken heads a number of

horses with large burns on their flanks. On the far side, the cement

structure of the local hospital is the only building that remains

standing. Its interior, however, has been burned out. It acts as a

landmark to guide us on our way.

Finally we reach the entrance of the park. A large proportion of the

populace has taken refuge there, but even the trees of the park are on

fire in several places. Paths and bridges are blocked by the trunks of

fallen trees and are almost impassable. We are told that a high wind,

which may well have resulted from the heat of the burning city, has

uprooted the large trees. It is now quite dark. Only the fires, which

are still raging in some places at a distance, give out a little light.

![[Tumbler Snapper Dog]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/proxy/AVvXsEhTh-SsipUvw4JQBtSsno2OzjA4gjG4aDgi3SxPMv82sG5lXEPlVNVCJmXHacbGLUzLEY-RYUsd0391YekSknRWvlUafrn18XrukbtbrtioTeqECMYI4M4bf9StVZGm0_AISmEbMZoC1A=s0-d-e1-ft)

Tumbler-Snapper DOG. Tumbler-Snapper DOG was a 20 kiloton airdrop detonated on May 1, 1952. Army and Marine troops participated in four of the eight Tumbler-Snapper shots.

At the far corner of the park, on the river bank itself, we at last

come upon our colleagues. Father Schiffer is on the ground pale as a

ghost. He has a deep incised wound behind the ear and has lost so much

blood that we are concerned about his chances for survival. The Father

Superior has suffered a deep wound of the lower leg. Father Cieslik and

Father Kleinsorge have minor injuries but are completely exhausted.

While they are eating the food that we have brought along, they tell

us of their experiences. They were in their rooms at the Parish

House -- it was a quarter after eight, exactly the time when we had heard

the explosion in Nagatsuke -- when came the intense light and immediately

thereafter the sound of breaking windows, walls and furniture. They were

showered with glass splinters and fragments of wreckage. Father

Schiffer was buried beneath a portion of a wall and suffered a severe

head injury. The Father Superior received most of the splinters in his

back and lower extremity from which he bled copiously. Everything was

thrown about in the rooms themselves, but the wooden framework of the

house remained intact. The solidity of the structure which was the work

of Brother Gropper again shone forth.

They had the same impression that we had in Nagatsuke: that the bomb

had burst in their immediate vicinity. The Church, school, and all

buildings in the immediate vicinity collapsed at once. Beneath the ruins

of the school, the children cried for help. They were freed with great

effort. Several others were also rescued from the ruins of nearby

dwellings. Even the Father Superior and Father Schiffer despite their

wounds, rendered aid to others and lost a great deal of blood in the

process.

In the meantime, fires which had begun some distance away are raging

even closer, so that it becomes obvious that everything would soon burn

down. Several objects are rescued from the Parish House and were buried

in a clearing in front of the Church, but certain valuables and

necessities which had been kept ready in case of fire could not be found

on account of the confusion which had been wrought. It is high time to

flee, since the oncoming flames leave almost no way open. Fukai, the

secretary of the Mission, is completely out of his mind. He does not

want to leave the house and explains that he does not want to survive

the destruction of his fatherland. He is completely uninjured. Father

Kleinsorge drags him out of the house on his back and he is forcefully

carried away.

![[Mike Fireball Close-up]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/proxy/AVvXsEjLqyjHhYOn5SLH8VC13t0EWV3PlhUa0dJ4ixKF1lwfGWIpRpbItGKKSZJ1_MCJG0vFskjKqM-6NZBJo49DsMppg8hyphenhyphenu9n7sx_GO906sFd3ZROmGxEl_AxK46K5lFRtnBgFZaJajvWscw=s0-d-e1-ft)

Ivy MIKE, slow-motion closeup of fireball. The Ivy MIKE shot was the first U.S. thermonuclear test using the Teller-Ulam radiation-implosion principle. It used liquid deuterium as the fusion fuel and yielded 10.7 megatons. The fireball reached a diameter of 3.5 miles.

Beneath the wreckage of the houses along the way, many have been

trapped and they scream to be rescued from the oncoming flames. They

must be left to their fate. The way to the place in the city to which

one desires to flee is no longer open and one must make for Asano Park.

Fukai does not want to go further and remains behind. He has not been

heard from since. In the park, we take refuge on the bank of the river. A

very violent whirlwind now begins to uproot large trees, and lifts them

high into the air. As it reaches the water, a waterspout forms which is

approximately 100 meters high. The violence of the storm luckily passes

us by. Some distance away, however, where numerous refugees have taken

shelter, many are blown into the river. Almost all who are in the

vicinity have been injured and have lost relatives who have been pinned

under the wreckage or who have been lost sight of during the flight.

There is no help for the wounded and some die. No one pays any attention

to a dead man lying nearby.

The transportation of our own wounded is difficult. It is not

possible to dress their wounds properly in the darkness, and they bleed

again upon slight motion. As we carry them on the shaky litters in the

dark over fallen trees of the park, they suffer unbearable pain as the

result of the movement, and lose dangerously large quantities of blood.

Our rescuing angel in this difficult situation is a Japanese Protestant

pastor. He has brought up a boat and offers to take our wounded up

stream to a place where progress is easier. First, we lower the litter

containing Father Schiffer into the boat and two of us accompany him. We

plan to bring the boat back for the Father Superior. The boat returns

about one-half hour later and the pastor requests that several of us

help in the rescue of two children whom he had seen in the river. We

rescue them. They have severe burns. Soon they suffer chills and die in

the park.

The Father Superior is conveyed in the boat in the same manner as

Father Schiffer. The theology student and myself accompany him. Father

Cieslik considers himself strong enough to make his way on foot to

Nagatsuke with the rest of us, but Father Kleinsorge cannot walk so far

and we leave him behind and promise to come for him and the housekeeper

tomorrow. From the other side of the stream comes the whinny of horses

who are threatened by the fire. We land on a sand spit which juts out

from the shore. It is full of wounded who have taken refuge there. They

scream for aid for they are afraid of drowning as the river may rise

with the sea, and cover the sand spit. They themselves are too weak to

move. However, we must press on and finally we reach the spot where the

group containing Father Schiffer is waiting.

Here a rescue party had brought a large case of fresh rice cakes but

there is no one to distribute them to the numerous wounded that lie all

about. We distribute them to those that are nearby and also help

ourselves. The wounded call for water and we come to the aid of a few.

Cries for help are heard from a distance, but we cannot approach the

ruins from which they come. A group of soldiers comes along the road and

their officer notices that we speak a strange language. He at once

draws his sword, screamingly demands who we are and threatens to cut us

down. Father Laures, Jr., seizes his arm and explains that we are

German. We finally quiet him down. He thought that we might well be

Americans who had parachuted down. Rumors of parachutists were being

bandied about the city. The Father Superior who was clothed only in a

shirt and trousers, complains of feeling freezing cold, despite the warm

summer night and the heat of the burning city. The one man among us who

possesses a coat gives it to him and, in addition, I give him my own

shirt. To me, it seems more comfortable to be without a shirt in the

heat.

![[Ivy MIKE distant fireball and cloud]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/proxy/AVvXsEiMgW62VSZPjj0xAZfRSS4y2aNJeQTFYppdZR6klZhzzcdwr9Aposz-8BEoPPo9Jl8lGCMqWavsqSm0YNEIGQg73ycTzxFV_8TF0FLq0puA-noyQv4ayS5AoTPFGMEGvvmlJCdJaocoQA=s0-d-e1-ft)

Ivy MIKE distant fireball and cloud. This clip shows a real-time view of MIKE from a safe distance.

In the meantime, it has become midnight. Since there are not enough

of us to man both litters with four strong bearers, we determine to

remove Father Schiffer first to the outskirts of the city. From there,

another group of bearers is to take over to Nagatsuke; the others are to

turn back in order to rescue the Father Superior. I am one of the

bearers. The theology student goes in front to warn us of the numerous

wires, beams and fragments of ruins which block the way and which are

impossible to see in the dark. Despite all precautions, our progress is

stumbling and our feet get tangled in the wire. Father Kruer falls and

carries the litter with him. Father Schiffer becomes half unconscious

from the fall and vomits. We pass an injured man who sits all alone

among the hot ruins and whom I had seen previously on the way down.

On the Misasa Bridge, we meet Father Tappe and Father Luhmer, who

have come to meet us from Nagatsuke. They had dug a family out of the

ruins of their collapsed house some fifty meters off the road. The

father of the family was already dead. They had dragged out two girls

and placed them by the side of the road. Their mother was still trapped

under some beams. They had planned to complete the rescue and then to

press on to meet us. At the outskirts of the city, we put down the

litter and leave two men to wait until those who are to come from

Nagatsuke appear. The rest of us turn back to fetch the Father Superior.

Most of the ruins have now burned down. The darkness kindly hides the

many forms that lie on the ground. Only occasionally in our quick

progress do we hear calls for help. One of us remarks that the

remarkable burned smell reminds him of incinerated corpses. The upright,

squatting form which we had passed by previously is still there.

Transportation on the litter, which has been constructed out of

boards, must be very painful to the Father Superior, whose entire back

is full of fragments of glass. In a narrow passage at the edge of town, a

car forces us to the edge of the road. The litter bearers on the left

side fall into a two meter deep ditch which they could not see in the

darkness. Father Superior hides his pain with a dry joke, but the litter

which is now no longer in one piece cannot be carried further. We

decide to wait until Kinjo can bring a hand cart from Nagatsuke. He soon

comes back with one that he has requisitioned from a collapsed house.

We place Father Superior on the cart and wheel him the rest of the way,

avoiding as much as possible the deeper pits in the road.

![[Ivy MIKE Cloud]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/proxy/AVvXsEjqRg32LsTA4PtJH3Xc9oU55_jZUXc65vNr4mQv9JNXqu84bftvd9IfVtPtQg-UKC96PlHua6hP5WugNWJBr-s86Ze8CzIlhkaAkeLsSrQbZyK51rr3HtLsbiiNxfwOBQiikSSz8aSjgQ=s0-d-e1-ft)

Ivy MIKE, later cloud stage. The MIKE cloud eventually rose to a height of 20 miles (into the stratosphere) and spread out to a width of 100 miles.

About half past four in the morning, we finally arrive at the

Novitiate. Our rescue expedition had taken almost twelve hours.

Normally, one could go back and forth to the city in two hours. Our two

wounded were now, for the first time, properly dressed. I get two hours

sleep on the floor; some one else has taken my own bed. Then I read a

Mass in gratiarum actionem, it is the 7th of August, the anniversary of

the foundation of our society. Then we bestir ourselves to bring Father

Kleinsorge and other acquaintances out of the city.

We take off again with the hand cart. The bright day now reveals the

frightful picture which last night's darkness had partly concealed.

Where the city stood everything, as far as the eye could reach, is a

waste of ashes and ruin. Only several skeletons of buildings completely

burned out in the interior remain. The banks of the river are covered

with dead and wounded, and the rising waters have here and there covered

some of the corpses. On the broad street in the Hakushima district,

naked burned cadavers are particularly numerous. Among them are the

wounded who are still alive. A few have crawled under the burnt-out

autos and trams. Frightfully injured forms beckon to us and then

collapse. An old woman and a girl whom she is pulling along with her

fall down at our feet. We place them on our cart and wheel them to the

hospital at whose entrance a dressing station has been set up. Here the

wounded lie on the hard floor, row on row. Only the largest wounds are

dressed. We convey another soldier and an old woman to the place but we

cannot move everybody who lies exposed in the sun. It would be endless

and it is questionable whether those whom we can drag to the dressing

station can come out alive, because even here nothing really effective

can be done. Later, we ascertain that the wounded lay for days in the

burnt-out hallways of the hospital and there they died.

We must proceed to our goal in the park and are forced to leave the

wounded to their fate. We make our way to the place where our church

stood to dig up those few belongings that we had buried yesterday. We

find them intact. Everything else has been completely burned. In the

ruins, we find a few molten remnants of holy vessels. At the park, we

load the housekeeper and a mother with her two children on the cart.

Father Kleinsorge feels strong enough, with the aid of Brother Nobuhara,

to make his way home on foot. The way back takes us once again past the

dead and wounded in Hakushima. Again no rescue parties are in evidence.

At the Misasa Bridge, there still lies the family which the Fathers

Tappe and Luhmer had yesterday rescued from the ruins. A piece of tin

had been placed over them to shield them from the sun. We cannot take

them along for our cart is full. We give them and those nearby water to

drink and decide to rescue them later. At three o'clock in the

afternoon, we are back in Nagatsuka.

After we have had a few swallows and a little food, Fathers Stolte,

Luhmer, Erlinghagen and myself, take off once again to bring in the

family. Father Kleinsorge requests that we also rescue two children who

had lost their mother and who had lain near him in the park. On the way,

we were greeted by strangers who had noted that we were on a mission of

mercy and who praised our efforts. We now met groups of individuals who

were carrying the wounded about on litters. As we arrived at the Misasa

Bridge, the family that had been there was gone. They might well have

been borne away in the meantime. There was a group of soldiers at work

taking away those that had been sacrificed yesterday.

![[Ivy KING]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/proxy/AVvXsEjVXUMclsPiepjrgI1_TuwNsCqx6bODAJblmswTZsn40OzgYj68OI8u0jIiC_xR_b0dEIAo5Xbj2cwg91ee0c0m2MGF1wWV6VnYLYY_vwbh_1QUGdENwMh9TyTDzQXqLLmV-OOwYLKTdg=s0-d-e1-ft)

Ivy KING detonation. Ivy KING was an air-drop of the "Super-Oralloy" all-fission bomb, with a yield of 500 kilotons.

More than thirty hours had gone by until the first official rescue

party had appeared on the scene. We find both children and take them out

of the park: a six-year old boy who was uninjured, and a twelve-year

old girl who had been burned about the head, hands and legs, and who had

lain for thirty hours without care in the park. The left side of her

face and the left eye were completely covered with blood and pus, so

that we thought that she had lost the eye. When the wound was later

washed, we noted that the eye was intact and that the lids had just

become stuck together. On the way home, we took another group of three

refugees with us. They first wanted to know, however, of what

nationality we were. They, too, feared that we might be Americans who

had parachuted in. When we arrived in Nagatsuka, it had just become

dark.

We took under our care fifty refugees who had lost everything. The

majority of them were wounded and not a few had dangerous burns. Father

Rektor treated the wounds as well as he could with the few medicaments

that we could, with effort, gather up. He had to confine himself in

general to cleansing the wounds of purulent material. Even those with

the smaller burns are very weak and all suffered from diarrhea. In the

farm houses in the vicinity, almost everywhere, there are also wounded.

Father Rektor made daily rounds and acted in the capacity of a

painstaking physician and was a great Samaritan. Our work was, in the

eyes of the people, a greater boost for Christianity than all our work

during the preceding long years.

Three of the severely burned in our house died within the next few

days. Suddenly the pulse and respirations ceased. It is certainly a sign

of our good care that so few died. In the official aid stations and

hospitals, a good third or half of those that had been brought in died.

They lay about there almost without care, and a very high percentage

succumbed. Everything was lacking: doctors, assistants, dressings,

drugs, etc. In an aid station at a school at a nearby village, a group

of soldiers for several days did nothing except to bring in and cremate

the dead behind the school.

During the next few days, funeral processions passed our house from

morning to night, bringing the deceased to a small valley nearby. There,

in six places, the dead were burned. People brought their own wood and

themselves did the cremation. Father Luhmer and Father Laures found a

dead man in a nearby house who had already become bloated and who

emitted a frightful odor. They brought him to this valley and

incinerated him themselves. Even late at night, the little valley was

lit up by the funeral pyres.

![[Castle BRAVO test]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/proxy/AVvXsEij0jyIqbDOYm3nBtTTmCE5k7oPnE9Nfi9UPcZjuhjmAabDluWMrNNk5A3gLX2fCktDUKGjkxgabWG7cnbPHQBTayrD8LEGegk0Hy0K8r7mVVD2D-p7hTVSank_fhEdg4iSwCx-CpK75g=s0-d-e1-ft)

Castle BRAVO test. The Castle BRAVO test on March 1, 1954, yielded 15 megatons, the largest nuclear weapon ever detonated by the United States. By accident the inhabited atolls of Rongelap, Rongerik and Utirik were contaminated with fallout, as was the Japanese fishing trawler Fukuryu Maru or Lucky Dragon. The controversy over fallout that simmered around the Nevada Test Site erupted into international alarm.

We made systematic efforts to trace our acquaintances and the

families of the refugees whom we had sheltered. Frequently, after the

passage of several weeks, some one was found in a distant village or

hospital but of many there was no news, and these were apparently dead.

We were lucky to discover the mother of the two children whom we had

found in the park and who had been given up for dead. After three weeks,

she saw her children once again. In the great joy of the reunion were

mingled the tears for those whom we shall not see again.

The magnitude of the disaster that befell Hiroshima on August 6th was

only slowly pieced together in my mind. I lived through the catastrophe

and saw it only in flashes, which only gradually were merged to give me

a total picture. What actually happened simultaneously in the city as a

whole is as follows: As a result of the explosion of the bomb at 8:15,

almost the entire city was destroyed at a single blow. Only small

outlying districts in the southern and eastern parts of the town escaped

complete destruction. The bomb exploded over the center of the city. As

a result of the blast, the small Japanese houses in a diameter of five

kilometers, which compressed 99% of the city, collapsed or were blown

up. Those who were in the houses were buried in the ruins. Those who

were in the open sustained burns resulting from contact with the

substance or rays emitted by the bomb. Where the substance struck in

quantity, fires sprang up. These spread rapidly.

The heat which rose from the center created a whirlwind which was

effective in spreading fire throughout the whole city. Those who had

been caught beneath the ruins and who could not be freed rapidly, and

those who had been caught by the flames, became casualties. As much as

six kilometers from the center of the explosion, all houses were damaged

and many collapsed and caught fire. Even fifteen kilometers away,

windows were broken. It was rumored that the enemy fliers had spread an

explosive and incendiary material over the city and then had created the

explosion and ignition. A few maintained that they saw the planes drop a

parachute which had carried something that exploded at a height of

1,000 meters. The newspapers called the bomb an "atomic bomb" and noted

that the force of the blast had resulted from the explosion of uranium

atoms, and that gamma rays had been sent out as a result of this, but no

one knew anything for certain concerning the nature of the bomb.

How many people were a sacrifice to this bomb? Those who had lived

through the catastrophe placed the number of dead at at least 100,000.

Hiroshima had a population of 400,000. Official statistics place the

number who had died at 70,000 up to September 1st, not counting the

missing ... and 130,000 wounded, among them 43,500 severely wounded.

Estimates made by ourselves on the basis of groups known to us show that

the number of 100,000 dead is not too high. Near us there are two

barracks, in each of which forty Korean workers lived. On the day of the

explosion, they were laboring on the streets of Hiroshima. Four

returned alive to one barracks and sixteen to the other. 600 students of

the Protestant girls' school worked in a factory, from which only

thirty to forty returned. Most of the peasant families in the

neighborhood lost one or more of their members who had worked at

factories in the city. Our next door neighbor, Tamura, lost two children

and himself suffered a large wound since, as it happened, he had been

in the city on that day. The family of our reader suffered two dead,

father and son; thus a family of five members suffered at least two

losses, counting only the dead and severely wounded. There died the

Mayor, the President of the central Japan district, the Commander of the

city, a Korean prince who had been stationed in Hiroshima in the

capacity of an officer, and many other high ranking officers. Of the

professors of the University, thirty-two were killed or severely

injured. Especially hard hit were the soldiers. The Pioneer Regiment was

almost entirely wiped out. The barracks were near the center of the

explosion.

![[Castle ROMEO test]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/proxy/AVvXsEgj2ACzICjoVxfoQmcIFBd3t7ATcKBMMcpS-et2kDFGT0gpr0cp1y3l5Xbj8rab8ujlKRoHeawbU85PpCvoXI42Ksln8SUA80MH7IuPYU6wywEm3MYb-Q16YQcfTt2wDoUrfor4jC69Jw=s0-d-e1-ft)

Castle ROMEO test. The Castle ROMEO test yielded 11 megatons. It was detonated from a barge in the BRAVO crater.

Thousands of wounded who died later could doubtless have been rescued

had they received proper treatment and care, but rescue work in a

catastrophe of this magnitude had not been envisioned; since the whole

city had been knocked out at a blow, everything which had been prepared

for emergency work was lost, and no preparation had been made for rescue

work in the outlying districts. Many of the wounded also died because

they had been weakened by under-nourishment and consequently lacked in

strength to recover. Those who had their normal strength and who

received good care slowly healed the burns which had been occasioned by

the bomb. There were also cases, however, whose prognosis seemed good

who died suddenly. There were also some who had only small external

wounds who died within a week or later, after an inflammation of the

pharynx and oral cavity had taken place. We thought at first that this

was the result of inhalation of the substance of the bomb. Later, a

commission established the thesis that gamma rays had been given out at

the time of the explosion, following which the internal organs had been

injured in a manner resembling that consequent upon Roentgen

irradiation. This produces a diminution in the numbers of the white

corpuscles.

Only several cases are known to me personally where individuals who

did not have external burns later died. Father Kleinsorge and Father

Cieslik, who were near the center of the explosion, but who did not

suffer burns became quite weak some fourteen days after the explosion.

Up to this time small incised wounds had healed normally, but thereafter

the wounds which were still unhealed became worse and are to date (in

September) still incompletely healed. The attending physician diagnosed

it as leucopania. There thus seems to be some truth in the statement

that the radiation had some effect on the blood. I am of the opinion,

however, that their generally undernourished and weakened condition was

partly responsible for these findings. It was noised about that the

ruins of the city emitted deadly rays and that workers who went there to

aid in the clearing died, and that the central district would be

uninhabitable for some time to come. I have my doubts as to whether such

talk is true and myself and others who worked in the ruined area for

some hours shortly after the explosion suffered no such ill effects.

None of us in those days heard a single outburst against the

Americans on the part of the Japanese, nor was there any evidence of a

vengeful spirit. The Japanese suffered this terrible blow as part of the

fortunes of war ... something to be borne without complaint. During

this, war, I have noted relatively little hatred toward the allies on

the part of the people themselves, although the press has taken occasion

to stir up such feelings. After the victories at the beginning of the

war, the enemy was rather looked down upon, but when allied offensive

gathered momentum and especially after the advent of the majestic

B-29's, the technical skill of America became an object of wonder and

admiration.

The following anecdote indicates the spirit of the Japanese: A few

days after the atomic bombing, the secretary of the University came to

us asserting that the Japanese were ready to destroy San Francisco by

means of an equally effective bomb. It is dubious that he himself

believed what he told us. He merely wanted to impress upon us foreigners

that the Japanese were capable of similar discoveries. In his

nationalistic pride, he talked himself into believing this. The Japanese

also intimated that the principle of the new bomb was a Japanese

discovery. It was only lack of raw materials, they said, which prevented

its construction. In the meantime, the Germans were said to have

carried the discovery to a further stage and were about to initiate such

bombing. The Americans were reputed to have learned the secret from the

Germans, and they had then brought the bomb to a stage of industrial

completion.

![[Desert Rock IV dust]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/proxy/AVvXsEg04iEgManPN5ioSJp-ocIcND2TYC0qCQtBAqepMz7RZvvNGWfF67ar5SzpxVRENi7utvGqX-H9MoY60ePPDKE_UujHgYe_GOQfLPmRybOhaAKzNh4KwgCZwf74W1OySfglUlL7gOJreg=s0-d-e1-ft)

Desert Rock IV. The blast wave crossing the desert and hitting the troop trenches.

We have discussed among ourselves the ethics of the use of the bomb.

Some consider it in the same category as poison gas and were against its

use on a civil population. Others were of the view that in total war,

as carried on in Japan, there was no difference between civilians and

soldiers, and that the bomb itself was an effective force tending to end

the bloodshed, warning Japan to surrender and thus to avoid total

destruction. It seems logical to me that he who supports total war in

principle cannot complain of war against civilians. The crux of the

matter is whether total war in its present form is justifiable, even

when it serves a just purpose. Does it not have material and spiritual

evil as its consequences which far exceed whatever good that might

result? When will our moralists give us a clear answer to this question?

Fr.

John A. Siemes was a German Jesuit who had been evacuated with his

school from Tokyo to the Nagatsuke Novitiate in Hiroshima five months

before the American nuclear strike

via The Avalon Project: Documents in Law, History and Diplomacy, Lillian Goldman Law Library, Yale Law School

The shadows of the parapets are imprinted on the surface of the

bridge, 2,890 feet (880 meters) south-south-west of the hypocenter.

These shadows give a clue as to the exact location of the hypocenter: photo by U. S. Army, August 1945

An

aerial view shows workers wearing protective suits and masks work at a

construction site (C) of the shore barrier to stop radioactive water

from leaking into the sea, at the tsunami-crippled Fukushima Daiichi

nuclear power plant in Fukushima, in this photo taken by Kyodo August 9,

2013. Highly radioactive water from Japan's crippled Fukushima nuclear

plant is pouring out at a rate of 300 tons a day, officials said on

Wednesday, as Prime Minister Shinzo Abe ordered the government to step

in and help in the clean-up. The revelation amounted to an

acknowledgement that plant operator Tokyo Electric Power Co (Tepco) has

yet to come to grips with the scale of the catastrophe, 2 1/2 years

after the plant was hit by a huge earthquake and tsunami. Tepco only

recently admitted water had leaked at all: photo by Reuters / Kyodo, 9 August 2013

Dr. Shigeru Mita: Tokyo should no longer be inhabited (16 July 2014)

Why did I leave Tokyo?

To my fellow doctors, I closed the clinic in March 2014, which had

served the community of Kodaira for more than 50 years, since my

father’s generation, and I have started a new Mita clinic in

Okayama-city on April 21. [...] It is clear that Eastern Japan and

Metropolitan Tokyo have been contaminated with radiation [...]

contamination in the east part [of Tokyo] is 1000-4000 Bq/kg and the

west part is 300-1000 Bq/kg. [...] 0.5-1.5 Bq/kg before 2011. [...]

Tokyo should no longer be inhabited [...] Contamination in Tokyo is

progressing, and further worsened by urban radiation concentration [...]

radiation levels on the riverbeds [...] in Tokyo have increased

drastically in the last 1-2 years. [...] Ever since 3.11, everybody

living in Eastern Japan including Tokyo is a victim, and everybody is

involved. [...] The keyword here is “long-term low-level internal

irradiation.” This differs greatly from medical irradiation or simple

external exposure to radiation. [...] People are truly suffering from

this utter lack of support. [...] If the power to save our citizens and

future generations exists somewhere, it [is] in the hands of individual

clinical doctors ourselves. [...] Residents of Tokyo are unfortunately

not in the position to pity the affected regions of Tohoku because they

are victims themselves. Time is running short. [...]

Dr Mita on patient symptoms since 2011:

White blood cells, especially neutrophils, are decreasing among

children [...] Patients report nosebleed, hair loss, lack of energy,

subcutaneous bleeding, visible urinary hemorrhage, skin inflammations

[...] we began to notice changes in children’s blood test results around

mid-2013 [...] Other concerns I have include symptoms reported by

general patients, such as persistent asthma and sinusitis [...] high

occurrences of rheumatic polymyalgia [...] Changes are also noticeable

in the manifestation of contagious diseases such as influenza,

hand-foot-and-mouth disease and shingles. [...]

Dr. Shigeru Miita, in the newsletter of Association of Doctors in Kodaira (Tokyo), translation via WNSCR, 16 July 2014 (ENE News)

A helicopter flies over Japan's Fukushima Daiichi No. 1 nuclear reactor, 12 March 2011. An explosion blew the roof off the the unstable reactor north of Tokyo on Saturday, Japanese media said, raising fears of a meltdown at a nuclear plant damaged in the massive earthquake that hit Japan: photo by Kim Kyung-Hoon / Reuters, 12 March 2011

U.S. Ambassador to Japan Caroline Kennedy wearing a yellow helmet and a mask inspects the central control room for the Unit 1 and Unit 2 reactors of the tsunami-crippled Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant last month: photo by Toru Yamanaka / AP, May 2014

The corporate media silence on Fukushima has been deafening even

though the melted-down nuclear power plant’s seaborne radiation is now

washing up on American beaches.

Ever more radioactive water continues to pour into the Pacific.

At least three extremely volatile fuel assemblies are stuck high in

the air at Unit 4. Three years after the March 11, 2011 disaster,

nobody knows exactly where the melted cores from Units 1, 2 and 3 might

be.

Amid a dicey cleanup infiltrated by organized crime, still more massive radiation releases are a real possibility at any time.

Radioactive

groundwater washing through the complex is enough of a

problem that Fukushima Daiichi owner Tepco has just won approval for a

highly controversial ice wall

to be constructed around the crippled reactor site. No wall of this

scale and type has ever been built, and this one might not be ready for

two years. Widespread skepticism has erupted surrounding its potential

impact on the stability of the site and on the huge amounts of energy

necessary to sustain it. Critics also doubt it would effectively guard

the site from flooding and worry it could cause even more damage should

power fail.

Meanwhile, children nearby are dying. The rate of thyroid cancers

among some 250,000 area young people is more than 40 times normal.

According to health expert Joe Mangano,

more than 46 percent have precancerous nodules and cysts on their

thyroids. This is “just the beginning” of a tragic epidemic, he warns.

Harvey Wasserman: Fukushima is still a disaster, truthdig, 3 June 2014

A radiation detector marks 0.6 microsieverts, exceeding normal day data, near Shibuya train station in Tokyo: photo by AP / Kyodo, 15 March 2011

Tepco: “In 3.11, Reactor 2 possibly had [a large amount] of heat with fire-engine water touching the fuel” -- 7 August 2014

![Tepco “In 311, Reactor 2 possibly had [large amount] of heat with fire-engine water touching the fuel”](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/proxy/AVvXsEjM6qIP3Htibd6FFTk32F63hz6AhGlsllLdTKKawdJDJ5z6SrfRnwj86KBKJE5WmkRcp8X9-5milIVLMJP4T3ZReLhPp1xcIAqi2DNxEyGB7i9-XdVH_UQXhEdoDBgGze_GgOmU1mKzc0KVqhyNHG3-gm5tvU7N1g6o-_yEA_YjsxkvhRWa8wsM7mRKDu7-jy7tnwp-vudLnieXKiUfzVHDALTaZxAVr29DhQrd_A7xuvZzTEIa7uGgChynqdz8pYGQnHYPIlXd5enWziSyykSH3TYPn9-e8uzP-NIj7tPnX-TNm5qNuT4=s0-d-e1-ft)

Fukushima Daiichi No. 2 nuclear reactor, 10 April 2011: photo from Tepco News library via Fukushima Diary (Iori Mochizuki), 7 August 2014

The Zone (Zone 24), Chernobyl, 24 years after: photo by Lukasz1911. 2010

9 comments:

There's an edited bit (9 mins) from Fr. Siemes' testimony at 16:00 of this remarkable historical document "prepared by the United States War Department":

The Atom Strikes 1945: Offizieller Propagandafilm der USA!

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=IePeHB9_4Xw

A brilliant post, Tom, for a sad anniversary. I was too early for the duck-and-cover drills, but metal dog tags had a cachet of cool among our adolescent group. Their unacknowledged purpose was to help identify the charred corpses pulled from the schoolhouse rubble; or, if you survived, to indicate your blood type so that you could be given a transfusion of by-now irradiated blood. It was, after all, a period of optimistic fatalism.

Merci, L'Enfant.

Here's that link:

Enola Gay: Target: Hiroshima

Merci, Tom!

incredible personal documentation...once again Tom you bear witness to the overlooked/ignored or deliberately minimized crimes against humanity...

Thanks, Hazen and Michael, and I guess this is one case in which showing your age amounts to showing your stripes, as a veteran -- that is, internally traumatised survivor of the global war machine over its many campaigns and seasons, dating all the way back to the prehistoric time when the brutality was merely senseless slaughter, not yet dressed up as a video game or fronted by quite such pseudo-sophisticated armies of paid liars as are propped in place now.

Yes, that protracted period of blind optimistic fatalism which held the carefully minimized crimes off at arm's length through routine denial and the laughably transparent sort of p.r. attempted in The Atom Strikes -- I think those must have been the good old days.

Looking into some of the records which have been disclosed, one learns that the secret super-weapon program which had been underway for some years was completely unknown to the hat salesman Truman until FDR died and somebody had to inform the new POTUS that among the toys he had inherited was this bomb program which had already cost $2 billion. You can just see Truman's eyes lighting up, like on Christmas morning back in Kansas City. His logic was, Well, since I've got it, why not use it (memos show that he also privately feared that he might be impeached if he didn't). So the air attacks on Japan were then restricted (so as to keep things clean for the nuclear experiment) in three specific areas, designated as target options: Hiroshima, Nagoya (Nagasaki seems to have been a last-minute afterthought), Kyoto; the wife of the Secretary of Defense fancied herself an appreciator of Asian cultures, and leaned on her husband to have Kyoto struck from the list of options on grounds of its status as a venerable cultural landmark. As to the generally accepted view that the nuclear strikes ended the war, that's pure myth. The Russians were about to arrive, and no Japanese who had heard anything of the news of the past few years could be unaware that surrendering to the Americans, who after dropping their super-bombs on you would come in and hand out chocolate bars (bygones, and no hard feelings) was always going to be preferable to surrendering to the Russians, who would come in, drink the booze, rape the women, and wreck everything that wasn't already wrecked.

Talking of the etiquette of occupying forces -- today there comes the revelation from Gaza as to how the IDF occupying troops ("the most moral army in the world," as the Israeli Defense Minister called them back at the beginning of this latest campaign of wanton genocide) diverted themselves while occupying the homes of those they had displaced (perhaps this pattern of conduct is codified in the Protocols, how can an outsider know): steal anything of value, destroy the rest, use the furniture as w.c., carve vicious racist hate messages into what remains of the walls and leave the place a fetid stinking ruin of death and loss. Welcome home, villager.

By the by, Ed Sanders, the outstanding peace activist among poets of our antediluvian epoch, comments, re. the comfy little family tomb (er shelter) there in Ak-Ron, Michigan, pictured in the fourth photo:

"Yeah, the Rockefeller family

had plans to make billions 'pon billions

from fallout shelters

for the Masses"

American philanthropy, the kindest, gentlest form of profiteering ever known.

The Proustian bon-bon box of involuntary memory has discharged a phantasmagoric recovered salvo of dismal childhood phobias instilled by all that early hiding under the school desk, tacking up the blankets over the windows, being terrified of every night siren in the constantly siren-filled night, anxiously calculating on street maps the putative distance from epicenter (never an encouraging project, as no matter how it was computed, the West Side of Chicago never stopped looking vulnerable to instant incineration, upon the outbreak of Total War -- which was presumed inevitable -- only a matter of time). As the logic of Total War rarely arrived at pacific conclusions, one important element in all such calculations, when raised to the higher plane of military strategy, was the proximity of air raid shelter to trigger finger, "defense" to "deterrence". (As for shelters, we'd heard and seen films about but never actually seen one, in fact we didn't have those, only a few hicks from the sticks would have one, and after all what was a backyard shelter going to do for a crowded urban apartment block in any case?). In this regard I found Father Siemes' testimony altogether more useful that the contributions of, for example, the "writers" who weren't there, but came in later for the career op, and this would designate a broad arc of candidates from John Hersey to Margerite Duras. When one asks oneself who Siemes was, what he may have been doing there, and above all, what was happening to him, during the Occupation, when he was being grilled at hearings like the one represented in the scary (shudder of remembrance of things past) propaganda video, The Atom Strikes. Fr Siemes, unlike the makers of that film, appears not to have been butt-stupid. His question about the morality of Total War, at the end of his piece, answers itself. But at present, of course, the morality of Total War is no longer debated, any more than the morality of the sky being up, water wet or the Earth round. Indeed it's a question seldom explored in American "thought", historically -- though now and then there once came along, back in the mythic epoch of a half century ago, the odd provocative "comic" hypothetical like this one. "Laughter blows it to rags", a poet once proposed.

Post a Comment