Girls at sink. [Rosebud Indian Reservation of the

Sicangu Oyate, also known as the Sicangu Lakota or Brulé, of the Sioux

Group in South Dakota]:

photographer unknown for Department of the Interior, Bureau of Indian

Affairs, Rosebud Agency, 1938 (National Archives and Records

Administration)

Public Indian gathering. [Rosebud Indian Reservation of the

Sicangu Oyate, also known as the Sicangu Lakota or Brulé, of the Sioux

Group in South Dakota]:

photographer unknown for Department of the Interior, Bureau of Indian

Affairs, Rosebud Agency, c. 1936 (National Archives and Records

Administration)

Climate advocates and representatives from the Rosebud Sioux tribe of South Dakota

protest against the Keystone XL pipeline in front of US Senator Mary

Landrieu’s home in Washington. “I pledge my life to stop these people from harming our children and

our grandchildren and our way of life and our culture and our religion

here,” the tribe president, Cyril Scott, said on Monday. Scott

said he will close the reservation's borders if the government goes

through with the deal, which is scheduled to come up for a Senate vote

on Tuesday. Environmentalists believe the pipeline would increase US reliance on

fossil fuels and that the transport of tar sands oil across the United

States could have serious environmental consequences: photo by Gary Cameron/Reuters via the Guardian, 17 November 2014

Rosebud Sioux Tribe - House Vote On #KeystoneXL #Tarsands Pipeline An ‘Act Of War': image via Mike Hudema @MikeHudema, 17 November 2014

Rosebud Sioux declare #KeystoneXL an act of war. @MaryLandrieu @SenatorCarper @SenBennettCO are you listening? #NoKXL: image via 350 DC 350@_DC, 17 November 2014

Nebraska Sandhills, Hooker County #1. Seen from Nebraska Highway 97 south of the Dismal River: photo by Ammodramus, 12 October 2010

Nebraska Sandhills, Hooker County #2. Seen from Nebraska Highway 97 south of the Dismal River: photo by Ammodramus, 12 October 2010

Nebraska Sandhills, Hooker County #3. Seen from Nebraska Highway 97 south of the Dismal River: photo by Ammodramus, 12 October 2010

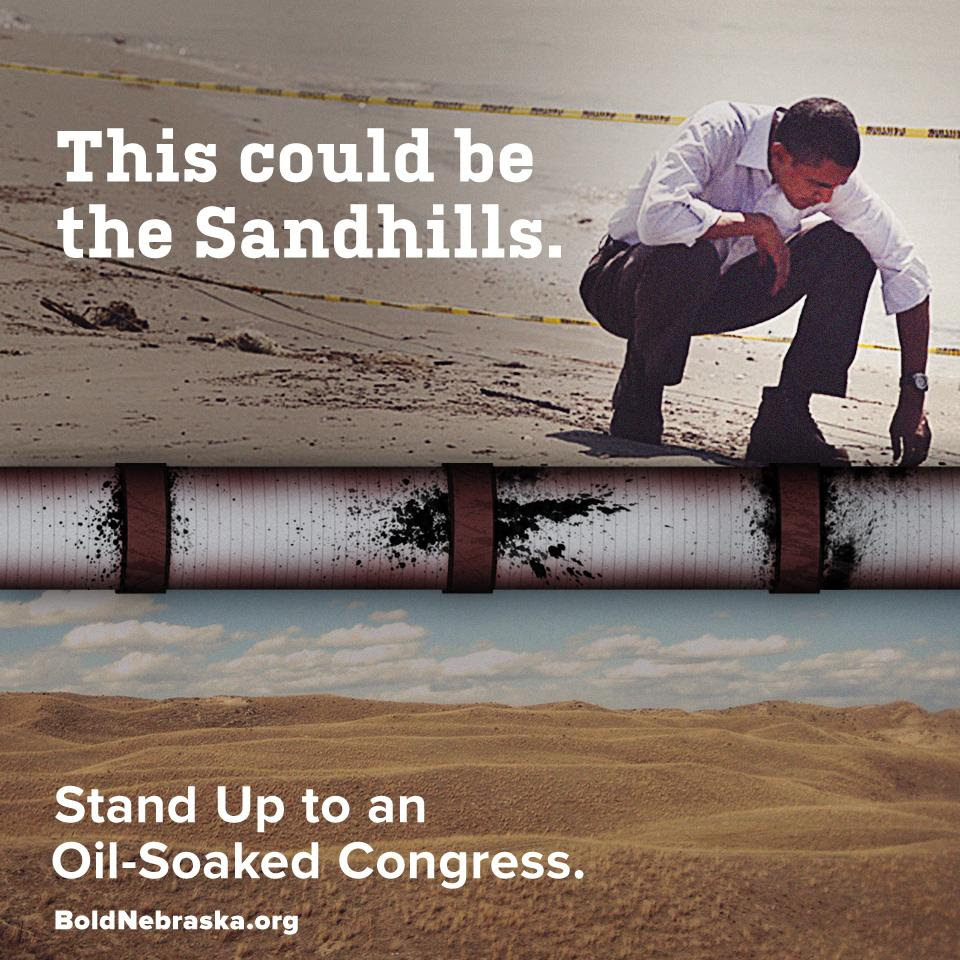

Ask your Senator to vote #nokxl. Stand up

to oil-soaked Congress, stand w/ farmers, ranchers, tribes,

@BarackObama: image via Jane Fleming Kleeb @janekleeb, 14 November 2014

All thank @CoryBooker @SenJohnsonSD @timkaine for standing w/ our families by voting #noonxl, protecting our water: image via Jane Fleming Kleeb @janekleeb, 15 November 2014

#NoKXL The Cowboy and Indian Alliance is standing strong: image via Jane Fleming Kleeb @janekleeb, 15 November 2014

Protesters lay pipeline on Sen. Landrieu's front yard. #KeystoneXL: image via Jeremy Diamond @JDiamond, 17 November 2014

@GregGreyCloud: #KeystoneXL will violate our treaties, we are here to call on Landrieu to stop this monster #noKXL: image via Energy Action @energyaction, 17 November 2014

#Canada #tarsands pipelines, including #Keystone, facing more U.S. lawsuits: image via Mike Hudema @MikeHudema, 13 November 2014

Map showing the extent of the oil sands in Alberta, Canada. The three oil sand deposits are known as the Athabasca Oil Sands, the Cold Lake Oil Sands, and the Peace River Oil Sands: image by Norman Einstein, 10 May 2006

Operational and proposed route of the Keystone Pipeline System (data source: TransCanada): image by Meclee, 21 July 2012

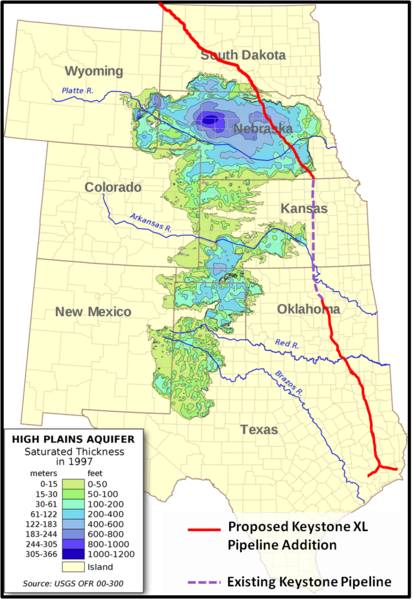

Saturated thickness map of Ogallala Aquifer with Keystone XL route layered: image by 570ajk, 17 November 2011, using aquifer map by kbh3rd

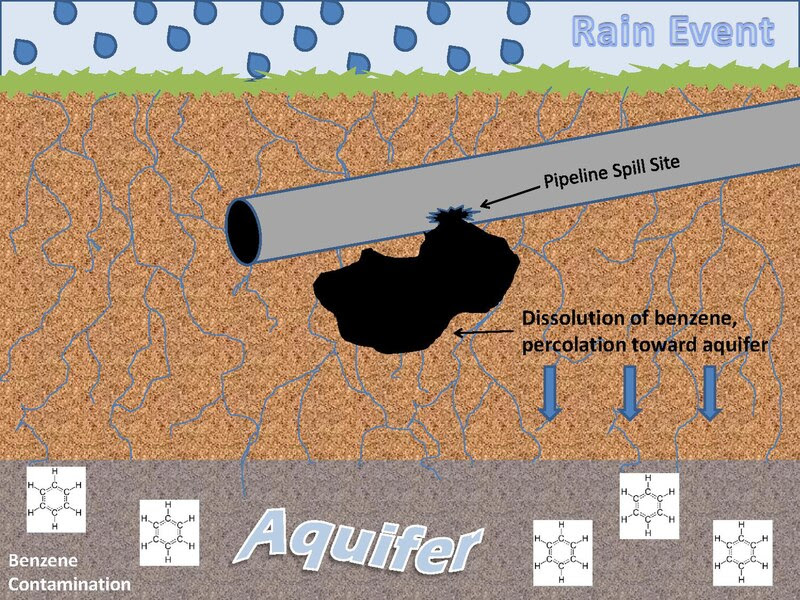

Scenario for benzene transport to groundwater from oil spill. Oil spills in or on soils have the potential to release benzene to the environment when a precipitation event carries dissolved benzene to groundwater sources: image by 570ajk, 28 October 2011

Truck hauling 36-inch pipe to build Keystone-Cushing pipeline SE of Peabody, Kansas. Location is Timber Rd and 20th St in Marion County. Looking south-west with rural Whitewater Center Church in background: photo by Steve Meirowsky, 10 July 2010

Pipes for the Keystone Pipeline, Nebraska: photo by shannonpatrick17, 13 August 2009

@climatekeith says #KeystoneXL means Canada won't

hit emission reduction targets: image via CBC-The Current

@TheCurrentCBC. 17 November 2014

How should this play any role in one of the world's largest aquifers? #TarSands #DirtyOil #WaterIsLife #NoKXL: image via tara zhaabowekwe @zhaabowekwe, 17 November 2014

Remember when windmills and solar panels caused long term, horrific environmental damage? No? Me either #KeystoneXL: image via Angel @angelmouse4, 17 November 2014

I'd rather not live on a planet that looks like this. And you? #NoKXL Plz read up on the #TarSands & RT: image via Tinsel Korey @tinselkoey, 17 November 2014

RT @climateprogress: How oil companies lost $17B

defying activists over Canada's #tarsands: image via Shawna

@S_WhiteBear, 5 November 2014

Senate votes #keystone Wed. Regardless of vote, #Tarsands companies will ship their oil to US: image via Daniel Grossman @grossmanmedia, 17 November 2014

#TarSands Reporting Project film to premier at Media Democracy Days Friday 7pm: image via Vancouver Observer @VanObserver, 7 November 2014

More than 100 birds die after landing on #tarsands waste ponds in Canada: image via Shawna @S_WhiteBear, 7 November 2014

Picture of #Tarsands tailing ponds created by

removal of Boreal forest - compared to Mordor by @londonmining #olsx:

image via Occupy London @OccupyLondon, 8 November 2014

Reports of birds landing in toxic #tarsands tailing lakes spark investigation: image via Mike Hudema @MikeHudema, 5 November 2014

Nearly 100 birds land in three #oilsands tailings ponds: image via Everett Coldwell @EverettColdwell, 5 November 20144

Athabasca oil sands mining field: NASA Earth Observatory image by Jesse Allen and Robert Simmon, acquired 29 July 2009 using EO-1 Advanced Land Rover data courtesy of the NASA EO-I team; caption by Holli Riebeek (NASA)

Nitrogen emissions from Athabasca oil sands mining operations, data acquired 2005 - 2010

Athabasca Oil Sands mining operations, Nitrogen emissions, data acquired 2005-2010: graphics by NASA Earth Observatory

Dust hangs in the sunset sky above the Suncor Millennium mine, an open-pit north of Fort McMurray, Alberta: photo by Peter Essick, in The Canadian Oil Boom: Scraping Bottom, National Geographic, March 2009

Athabasca oil sands mining field: NASA Earth Observatory image by Jesse Allen and Robert Simmon, acquired 29 July 2009 using EO-1 Advanced Land Rover data courtesy of the NASA EO-I team; caption by Holli Riebeek (NASA)

Athabasca Oil Sands: satellite image by NASA Earth Observatory, 23 July 1984 (NASA)

Athabasca Oil Sands: satellite image by NASA Earth Observatory, 28 September 1985 (NASA)

Athabasca Oil Sands: satellite image by NASA Earth Observatory, 14 August 1986 (NASA)

Athabasca Oil Sands: satellite image by NASA Earth Observatory, 18 September 1987 (NASA)

Athabasca Oil Sands: satellite image by NASA Earth Observatory, 4 September 1988 (NASA)

Athabasca Oil Sands: satellite image by NASA Earth Observatory, 6 August 1989 (NASA)

Athabasca Oil Sands: satellite image by NASA Earth Observatory, 24 July 1990 (NASA)

Athabasca Oil Sands: satellite image by NASA Earth Observatory, 27 July 1991 (NASA)

Athabasca Oil Sands: satellite image by NASA Earth Observatory, 13 July 1992 (NASA)

Athabasca Oil Sands: satellite image by NASA Earth Observatory, 17 August 1993 (NASA)

Athabasca Oil Sands: satellite image by NASA Earth Observatory, 26 July 1994 (NASA)

Athabasca Oil Sands: satellite image by NASA Earth Observatory, 24 September 1995 (NASA)

Athabasca Oil Sands: satellite image by NASA Earth Observatory, 22 June 1996 (NASA)

Athabasca Oil Sands: satellite image by NASA Earth Observatory, 12 August 1997 (NASA)

Athabasca Oil Sands: satellite image by NASA Earth Observatory, 5 July 1998 (NASA)

Athabasca Oil Sands: satellite image by NASA Earth Observatory, 15 June 1999 (NASA)

Athabasca Oil Sands: satellite image by NASA Earth Observatory, 13 September 2000 (NASA)

Athabasca Oil Sands: satellite image by NASA Earth Observatory, 7 August 2001 (NASA)

Athabasca Oil Sands: satellite image by NASA Earth Observatory, 11 September 2002 (NASA)

Athabasca Oil Sands: satellite image by NASA Earth Observatory, 30 September 2003 (NASA)

Athabasca Oil Sands: satellite image by NASA Earth Observatory, 28 June 2004 (NASA)

Athabasca Oil Sands: satellite image by NASA Earth Observatory, 5 October 2005 (NASA)

Athabasca Oil Sands: satellite image by NASA Earth Observatory, 21 August 2006 (NASA)

Athabasca Oil Sands: satellite image by NASA Earth Observatory, 30 July 2007 (NASA)

Athabasca Oil Sands: satellite image by NASA Earth Observatory, 25 July 2008 (NASA)

Athabasca Oil Sands: satellite image by NASA Earth Observatory, 14 September 2009 (NASA)

Athabasca Oil Sands: satellite image by NASA Earth Observatory, 3 October 2010 (NASA)

Athabasca Oil Sands: satellite image by NASA Earth Observatory, 15 May 2011 (NASA)

Nitrogen emissions from Athabasca oil sands mining operations, data acquired 2005 - 2010

Dust hangs in the sunset sky above the Suncor Millennium mine, an open-pit north of Fort McMurray, Alberta: photo by Peter Essick, in The Canadian Oil Boom: Scraping Bottom, National Geographic, March 2009

The oil sands industry has utterly

transformed this part of northeastern Alberta in just the past few

years, with astonishing speed. Where trapline and cabin once were, and the forest, there is

now a large open-pit mine. Here Syncrude, Canada's largest oil producer,

digs bitumen-laced sand from the ground with electric shovels five

stories high, then washes the bitumen off the sand with hot water and

sometimes caustic soda. Next to the mine, flames flare from the stacks

of an "upgrader," which cracks the tarry bitumen and converts it into

Syncrude Sweet Blend, a synthetic crude that travels down a pipeline to

refineries in Edmonton, Alberta; Ontario, and the United States.

Mildred Lake, meanwhile, is now dwarfed by its neighbor, the Mildred

Lake Settling Basin, a four-square-mile lake of toxic mine tailings. The

sand dike that contains it is by volume one of the largest dams in the

world.

Nor is Syncrude alone. Within a 20-mile radius

are a total of six mines that produce nearly three-quarters of a million

barrels of synthetic crude oil a day; and more are in the pipeline.

Wherever the bitumen layer lies too deep to be strip-mined, the industry

melts it "in situ" with copious amounts of steam, so that it can be

pumped to the surface. The industry has spent more than $50 billion on

construction during the past decade, including some $20 billion in 2008

alone. Before the collapse in oil prices last fall, it was forecasting

another $100 billion over the next few years and a doubling of

production by 2015, with most of that oil flowing through new pipelines

to the U.S. The economic crisis has put many expansion projects on hold,

but it has not diminished the long-term prospects for the oil sands. In

mid-November, the International Energy Agency released a report

forecasting $120-a-barrel oil in 2030 -- a price that would more than

justify the effort it takes to get oil from oil sands.

Nowhere on Earth is more earth being moved these days than in the

Athabasca Valley. To extract each barrel of oil from a surface mine, the

industry must first cut down the forest, then remove an average of two

tons of peat and dirt that lie above the oil sands layer, then two tons

of the sand itself. It must heat several barrels of water to strip the

bitumen from the sand and upgrade it, and afterward it discharges

contaminated water into tailings ponds like the one near Mildred Lake.

They now cover around 50 square miles. Last April some 500 migrating

ducks mistook one of those ponds, at a newer Syncrude mine north of Fort

McKay, for a hospitable stopover, landed on its oily surface, and died.

The incident stirred international attention -- Greenpeace broke into the

Syncrude facility and hoisted a banner of a skull over the pipe

discharging tailings, along with a sign that read "World's Dirtiest Oil:

Stop the Tar Sands."

The U.S. imports more oil from Canada than from any other nation, about

19 percent of its total foreign supply, and around half of that now

comes from the oil sands. Anything that reduces our dependence on Middle

Eastern oil, many Americans would say, is a good thing. But clawing and

cooking a barrel of crude from the oil sands emits as much as three

times more carbon dioxide than letting one gush from the ground in Saudi

Arabia. The oil sands are still a tiny part of the world's carbon

problem -- they account for less than a tenth of one percent of global CO2

emissions -- but to many environmentalists they are the thin end of the

wedge, the first step along a path that could lead to other, even

dirtier sources of oil: producing it from oil shale or coal. "Oil sands

represent a decision point for North America and the world," says Simon

Dyer of the Pembina Institute, a moderate and widely respected Canadian

environmental group. "Are we going to get serious about alternative

energy, or are we going to go down the unconventional-oil track? The

fact that we're willing to move four tons of earth for a single barrel

really shows that the world is running out of easy oil."

Robert Kunzig, in The Canadian Oil Boom: Scraping Bottom, National Geographic, March 2009

Photographer @ianwillms documents a typical day in Alberta's Fort McMurray: image via AACC @artsandclimate, 11 November 2014

Gas station attendants peer over their "Out of Gas" sign in Portland, on day before the state's requested Saturday closure of gasoline stations: photo by David Falconer for the Environmental Protection Agency's Documerica Project, November 1973 (US National Archives)

Trans-Alaska Pipeline at Mile O: photo by Sanao, 12 September 2004; image by The RedBurn, 25 November 2005 (The Joint Pipeline Office / U.S. Government)

The Trans-Alaska oil pipeline coming from underground, on the road between Fairbanks and Anchorage (the long route via Delta and Glenallen -- a great drive but very long): photo by Frank K., 22 March 2008

The Trans-Alaska oil pipeline running far into the horizon, taken on the road between Fairbanks and Anchorage: photo by Frank K., 22 March 2008

Trans-Alaska Pipeline, Kettle Lakes, Prudhoe Bay, Alaska: photo by Nick Bonzey, 10 July 2007

Trans-Alaska Pipeline: from here to forever (a 270 degree view): photo by Nick Bonzey, 14 July 2007

Trans-Alaska Oil Pipeline: photo by Marcin Klapczynski, 14 July 2005

Trace of the Denali Fault after the 7.9 magnitude earthquake of 3 November 2002, Alaska, USA. View south along the Trans-Alaska Pipeline System in the zone where it was engineered to cross the fault (the pipeline rests on sliders rather than rigid pillar supports). The fault trace passes beneath the pipeline between the 2nd and 3rd slider supports at the far end of the zone. A large arc in the pipe can be seen in the pipe on the right, due to shortening of the zigzag-shaped pipeline trace within the fault zone. It was snowing when the photo was taken: photo by Whhalbert, 7 November 2002 (United States Geological Survey)

Caribou walking next to a section of the Trans-Alaska Oil Pipeline north of the Brooks Range in Alaska: photo by Stan Shebs, July 1998

Alyeska Pipeline service Company's Fairbanks pipeyard, with more than 200 miles of 48-inch pipe. Most lengths are 50-to-60 feet: photo by Dennis Cowals for the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, August 1973 (U.S. National Archives)

A

State of Alaska Highway Department gravel pit located a mile east of

the Trans-Alaska Pipeline route. Contractors building the pipeline will

have to excavate pits similar to this where gravel is not easily

obtainable from watercourses: photo by Dennis Cowals for the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, August 1973 (U.S. National Archives)

Alaska

Pipeline route along Valdez River. View northeast across Valdez River

floodplain showing pipe storage yard, center foreground, which holds 418

miles of pipe. Yards at Fairbanks and Prudhoe Bay hold 238 and 168

Miles of pipe respectively. The community's airport, paved in the summer

of 1974, sits

at the base of West Peak (Elevation 5,255 Feet). Mile 788, along the

Alaska Pipeline Route: photo by Dennis Cowals for the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, August 1974 (U.S. National Archives)

Port

Valdez waters appear milky under some lighting conditions as a result

of suspended sediments dumped into the sea by the Lowe River and others

like it which annually dump tons of ground rock flour into the ocean.

This view shows Entrance Island at the right near the mouth of Port

Valdez, Mile 789, near the Alaska Pipeline route: photo by Dennis Cowals for the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, August 1974 (U.S. National Archives)

Birds killed by the Exxon Valdez oil spill: photo courtesy of the Exxon Valdez Oil Spill Trustee Council, 1989; image by KillerChihuahua, 27 October 2006

Eagles (Haliaetus leucocephalus) rescued from the Exxon Valdez oil spill, in the care of Raptor Education Group Inc.: photo by Mckennagene 4 October 2008

An oil-stained dead eagle lies on the shore after the Exxon Valdez spill: photo by John Lyle / Arlis, March 1989 via The Guardian, 24 March 2014

Staining the vista of the Chugach Mountains, the Exxon Valdez lies atop Bligh Reef two days after the grounding, in Prince William Sound, Alaska. Southbound from the trans-Alaska pipeline terminal at Valdez, the ship had met disaster after 28 miles, outside normal shipping lanes, with the captain absent from the bridge: photo by Natalie B. Fobes / NG, 26 March 1989 via The Guardian, 24 March 2014

A beach cleaning operation in Prince William Sound: photo by Bud Ehler/Arlis, 4 June 1989 via The Guardian, 24 March 2014

A modified C130 plane sprays dispersant on the Exxon Valdez oil spill area of the sea in the Gulf of Alaska: photo by Natalie Fobes / NG, 26 March 1989 via The Guardian, 24 March 2014

Oil leaches off an island beach in the Gulf of Alaska weeks after the Exxon Valdez incident: photo by Natalie Fobes/Corbis, April 1989 via The Guardian, 24 March 2014

Clouds hover over snowy peaks near Prince William Sound, Valdez, Alaska. Twenty-five years after the Exxon Valdez supertanker split open on a submerged reef and spilled 11 millions gallons of crude oil on 24 March 1989, legal fights continue. Experts thought the crude would be gone by 1995 but oil still clings to rocks on once-pristine beaches: photo by David McNew via The Guardian, 24 March 2014

9 comments:

i'll have to come back to finish this article, tom, but i want to reach out to tell you how sad i am. james just came back to canada from the U.S. and told me that the pipeline had passed. i've not been following news lately. so tired. overwhelmed. and all i could manage as a response was to feel sick and cry.

this is one of those times (and there are those times, more often it seems beneath this administration, and i stress the word beneath) in which i am embarrassed to be canadian, yet another (group of) human(s) acting blindly under the prime directives of plenty and now.

xo

erin

thank you Tom for bringing all these images together to make it irrefutably clear what's going on and what there will be more of if this project and ones like it aren't stopped...as challenging as that might be, it can be done, as has been proven in the past...

Great array of photos. The pipeline runs through our hearts.

The energy companies are desperate to get their product to market before the economy collapses, so damn the public and the environment; and most of all, damn the future. We map our own destruction. Fear and greed drive this devastation. Sen. Warner, (One Percenter, Virginia.) nominal liberal, co-sponsored the KXL bill.

Already—even at this stage—we inhabit a ruin.

Tom,

It’s never enough, is it? First our country kills and displaces native people; it destroys their food source; it tries to take their language away; it sends their children to white schools; and it has done countless more actions to humiliate them. Now this newest absurdity will surely ruin the only land they have, and in the process will destroy the water source of the upper plains and the land to the south. Rivers will be more polluted than imaginable. Greed wins. We all lose. We might as well turn the lights out now – we’re headed for the darkest of days. In spirit, I’ll be linking arms with those who wish to protect the land where native grasses grow and water runs clear.

Marcia

P.S. L. told me to let you know that he appreciates all the thought and research that you put into your blogs.

This was like watching a horror movie. Thanks for assembling all this sad information.

Tom,

The States, perhaps more unequivocally than any other democracy, is well inline in approaching the conjunctive idea of "a well-oiled machine". No time is soon enough to give up on As-long-as-the-machines-keep-running-we-don't-have-to nonsense.

Marcia nails it on its filthy head: All this has come to pass because greedy man (predominately white)speak with oily forked tongue. Thanks for being an exception, Tom.

It's painful to look this problem in the eye, given the Pogo Paradox, it might always turn out to be us.

The pushy turncoat bayou Dem who boosted the Keystone vote for her own political purposes (typical of the colossally myopic, meanspirited new visionaries of the Right) may not have got her way this time round, but there's a sort of a terrible law of the energy industry at work here: once somebody's figured out a way to extract, no matter the degree of risk and danger and cost in the extraction process, and no matter the foul quality of the product extracted (tar sands of course being the foulest yet discovered), somebody is going to extract it, and soon.

The Republicans will rush up the same bill again once they think they have the numbers, and of course TransCanada already has a backup plan for offloading their poisonous treasure, they can just back up a present pipeline or maybe build a new one whatever it takes to move that sludge across the continent for transhipping to refineries, maybe in India, and at the end of the day, more or less inevitably, to end up here.

Whence, naturally, it will begin to come back to us, particle by particle, in the planetary karmic boomerang effect.

Post a Comment