London, UK. Workers inside the the Lloyds building pause during a service of remembrance held at the building for Armistice Day: photo by Chris Radburn / PA via The Guardian, 11 November 2014

ὦ ξεῖν', ἀγγέλλειν Λακεδαιμονίοις ὅτι τῇδε

κείμεθα τοῖς κείνων ῥήμασι πειθόμενοι.

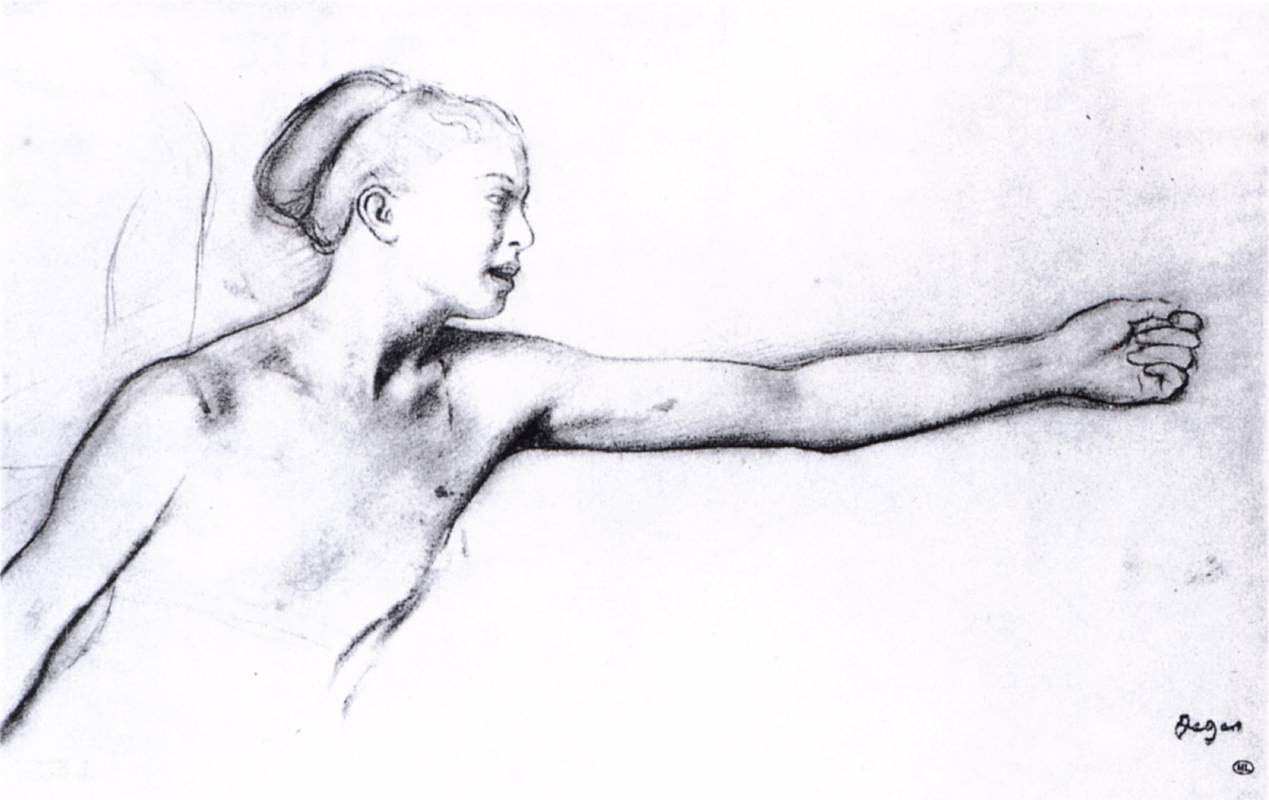

Spartan Girl: Edgar Degas, c. 1860. pencil on paper, 229 x 360 mm (Musée d'Orsay, Paris)

Take this news to the Lakedaimonions, friend,

That here we lie, who followed your command.

Epigram 8: For the Spartan Dead at Thermopylae (480 B.C.) [Epitaph on the Cenotaph of Thermopylae, recorded by Herodotus]: Simonides of Ceos (c. 556-468 BC), translated by Peter Jay, in The Greek Anthology and Other Ancient Epigrams, 1981

View of the Thermopylae pass at the area of the Phocian Wall. In ancient times the coastline was where the modern road lies, or even closer to the mountain: photo by Fkerasar, 17 April 2007

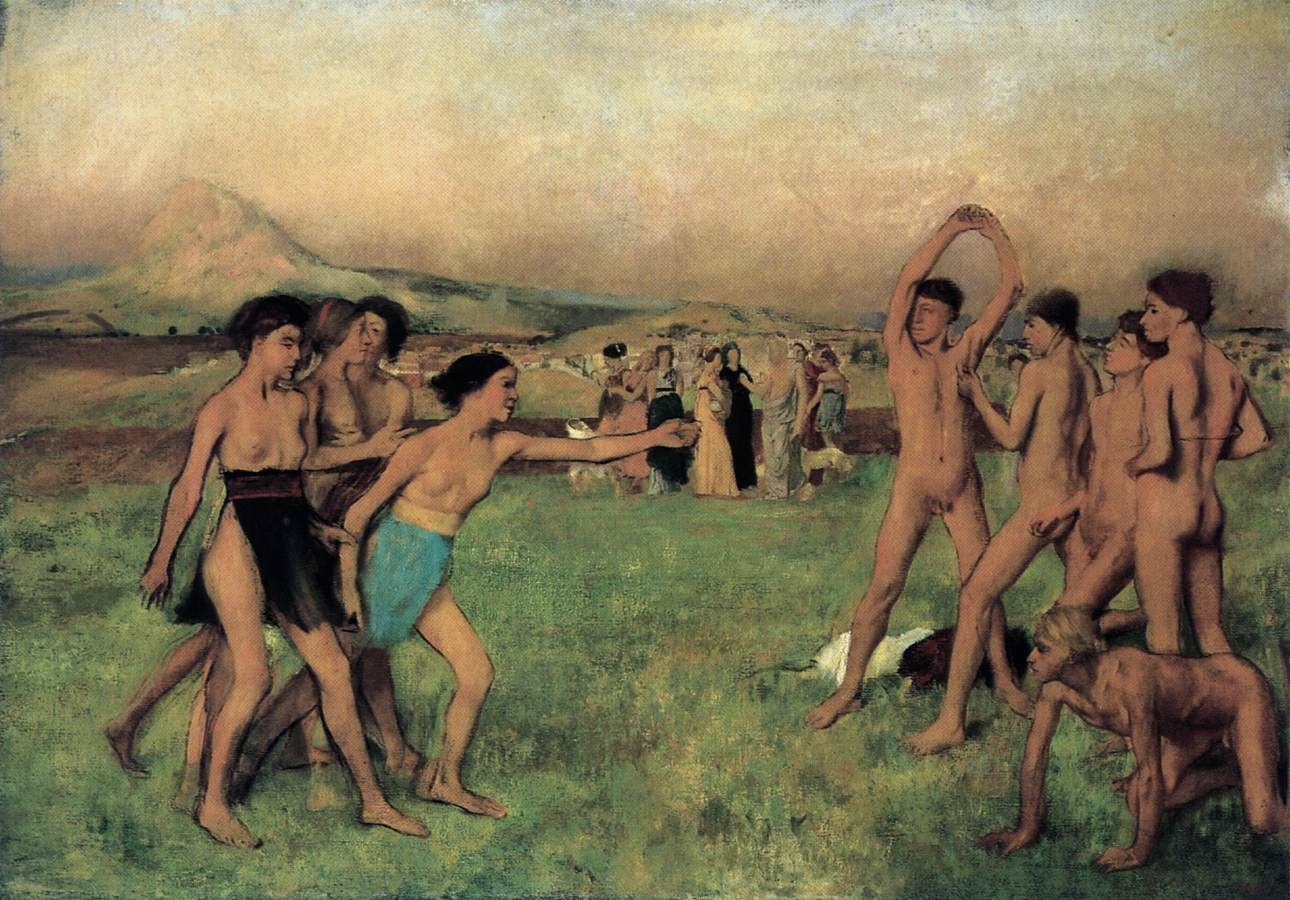

Young Spartans Exercising: Edgar Degas, c. 1860, oil on canvas, 109 x 155 cm (National Gallery, London)

The hard

fate of the vastly outnumbered Greek warriors under King Leonidas of

Sparta making what would become perhaps history's most famous last stand

at Thermopylae is condensed into this appropriately laconic cenotaph

inscription for the crazy-brave fallen ones. Brief as it was, it was inarguably their moment

(well, theirs, and the Persians' also, of course, in another sort of

way); happy chance the poet came by before the elements had conspired to

render the road marker illegible. The inscription was

recorded by Herodotus, and attributed by him and some (though not all)

later scholars to the renowned public-performance lyricist Simonides of

Ceos, popular composer of after-dinner epigrams,

particularly noted for his epitaphs for the dead heroes of the Persian

wars. This inscription has also provided a common object lesson in the

effective deployment of the Greek elegiac metre, and has been held up as

such for the

instruction of generations of students of prosody down through the

centuries. As it happens this was the first Greek poem I was, as a

beginning student of classics, made to learn by heart. While at present I

must admit to having some difficulty remembering much of anything at

all, this is one poem which, in its original form, I find I simply

cannot forget. Perhaps this curious mnemonic persistence is down to the

inscription's "message", which remains irritatingly relevant to human

existence. I mean, alas, it doesn't take a genius to see that if "good"

doomed causes never quite seem to go out of style, neither do

acquiescent (if not in fact heroic) players in the game. The first rule

of this patriotism game may be that players in it must be willing to

"take one for the side", even if they no longer or perhaps never in the

first place actually did know which side they're on; or, moreover,

whether there was really ever any other side at all, but only the one. In this sense, to say one gave up, or would ceded

be the better word, one's small existence, for what it may be worth, to

the big Good Cause, or "the System", represented here by the

Lakedaimonians, would constitute more a Willie Loman than a Leonidas Moment. But of course this is all just an example of (object lesson in) "playing with words". Willie who? Leonidas diCaprio?

And I do wish Leo would get on with putting that sword away. As

Perugino shows it, the job looks so -- halfway done. For commitment to a

losing cause to be worth anything at all it has to go all the way.

Carnival Prince Lambert I, Mardi Gras: photo by Peter Mokveld, n.d. (Spaarnestad Photo / Nationaal Archief)

Lyon, France. Veterans take part in an Armistice Day ceremony: photo by Jeff Pachoud / AFP via The Guardian, 11 November 2014

Famous Men of Antiquity: Pietro Perugino, 1497-1500, fresco, 291 x 400 cm (Collegio del Cambio, Perugia)

Virginia, US. A truck with an explosive is detonated during a US diplomatic security service high threat training programme held at a mock town named Erehwon -- nowhere spelt backwards -- on a rural military base: photo by Pablo Martinez Monsivais / AP via The Guardian, 11 November 2014

Famous Men of Antiquity (detail): Pietro Perugino, 1497-1500, fresco, 291 x 400 cm (Collegio del Cambio, Perugia)

3 comments:

Thanks, Tom. A beautiful & succinct poem. I'm glad it got stuck in your memory.

amen brother

We've had so many bad good causes and losing winning wars, by this point, it all kind of runs together. Going to war for the corporate nation state seems such an abstract concept, when you stop and think about it. Of course you're not meant to stop and think about it -- that's the disinformation function of the corporate nation state, always busy at its necessary work.

I was once trained to take up a "leadership" rôle in the colonial military actions of a corporate nation state, and disgracefully declined the opportunity. This has affected everything that's happened since. Big deal, as though the malfunction of one small part in a huge machine mattered to anybody, much less the machine. Do any of the errant working parts on the Philae Lander care?

But coincidentally, in the past few months my whereabouts have been sussed by my high school class reunion representatives, after all these centuries.

And now with Veteran's Day I am getting bittersweet updates on everyone's military memories.

Everyone was a candidate for the line of fire in Southeast Asia. Many went to serve. Some came back. A few of them wrote books about it.

Who am I to judge anybody. I simply continue to think this sort of war, a thing conducted by heroic or not heroic suckers on behalf of some spurious and incompletely understood patriotic cause or other, imposed as a duty by those whose "national interests" (read: private gain) is served from afar, sucks.

And when it comes right down to the push and shove and kicking sand in faces, you've got to wonder how many of those reverent Lloyd's Bank soldiers, there in the grand cathedral of Money beneath whose pillars our distorted mutation of the primate chain has slunk away to worship and die of its own sheer offensiveness to the universe, would really be willing to strap it on and take one for the side.

Post a Comment