BREAKING: #BlueSkyM has sent a distress signal. It has been reported to be carrying 100s of refugees: image via Marine Traffic @MarineTraffic, 30 December 2014

still traveling further

still, after the tenth year, a spear

planted within

ما زلت

ما زلت يا مسافرة

ما زلت بعد السنة العاشرة

مزروعة...كالرمح في الخاصرة

ما زلت يا مسافرة

ما زلت بعد السنة العاشرة

مزروعة...كالرمح في الخاصرة

Still: Nizar Qabbani (1923-1998)

Bighorn sheep, possibly female, resting on forest floor, Kootenay National Park, British Columbia: photo by Wing-Chi Poon, 6 July 2005

Damascus on a snowy day: photo by Elph, 30 January 2008

1 Distress call

Moldova cargo vessel #BlueSkyM appears carrying Syrian migrants from #Turkey, #Greek Navy Special Forces mobilized: image via e-Amyna @e_amyna, 30 December 2014

Greece searches for migrant ship after distress call: Call came from

passenger on cargo ship believed to be carrying between 400 and 600

migrants in Ionian Sea: Associated Press in Athens, 30 December 2014

Greece is sending a navy frigate and a helicopter to locate a cargo ship

believed to be carrying hundreds of migrants in the northern Ionian Sea

after authorities received a distress call from someone on board.

The ship, the Moldovan-flagged Blue Sky M, was sailing in poor

weather near the tiny island of Othonoi, north-west of Corfu. A merchant

marine ministry official said the distress call came from one of the

passengers on board the ship, which is believed to be carrying between

400 and 600 migrants.

The

incident comes two days after a passenger ferry, the Norman Atlantic,

with more than 400 people on board, caught fire in the same area,

leading to a huge rescue operation by Italian and Greek coastguard and

military officials. At least 10 people died in that incident, and the

search is continuing for others feared missing.

The Greek frigate Navarino, which is heading to locate the cargo

ship, was in the area assisting in the rescue operation for the Norman

Atlantic.

Greek coastguard officers set off from Corfu harbour in response to a distress signal from a ship in the area: photo by Maria Tzora/EPA, 30 December 2014

Four

migrants found dead on cargo ship in Italy:

Greece sent emergency services to the Blue Sky M, carrying 900 migrants,

after alarm call near Corfu coast: Reuters, 31 December 2014

Four

migrants were found dead on a cargo ship which was taken to Italy after

apparently being abandoned by its crew in Greek waters, the Italian Red

Cross said on Wednesday.

The Blue Sky M was carrying an estimated 900 migrants when it was spotted drifting near the coast of Corfu on Tuesday.

Greece sent its navy and coastguard with a military helicopter to the scene in

response to an alarm call and Italian coast guard officials later

boarded to check if the ship could navigate properly.

Most of the people on board were Syrian, Red Cross spokeswoman Mimma

Antonagi told Reuters from the province of Lecce where the migrants

arrived.

Medics help migrants after they arrive on board the Blue Sky M cargo ship at the Gallipoli harbour southern Italy: photo by Stringer/Italy/Reuters, 31 December 2014

The exact number of people on board is still not known, Antonagi

said. Italian authorities had originally thought there were 600-700

passengers by the time the ship reached in the small port city of

Gallipoli, the estimated number had risen.

The dead have been taken to a hospital and survivors to public

buildings where an identification process is under way. They are

believed to be illegal immigrants.

Greek state television reported on Tuesday that the alarm was raised

because armed men were on board, but the defence and shipping ministries

did not confirm this.

Civil

war in Syria and anarchy in Libya have swelled the number of people

crossing the Mediterranean in rickety boats this year, often bound for

Italy and Greece.

The United Nations refugee agency said 160,000 seaborne migrants

arrived in Italy by November 2014 and a further 40,000 in Greece.

Thousands more have died attempting the journey.

Italian emergency services help migrants from the ship Blue Sky M, which was left on autopilot by people smugglers: photo by Nunzio Giove/AFP via The Guardian, 2 January 2015

One of the schools of #Gallipoli turned into refugee camp for #BlueSkyM migrants: image via Gilberto Busti @gilbusti, 30 December 2014

Migrant boat #BlueSkyM adrift: image via Girija Shettar @GirijaShettar, 31 December 2014

Migrant ship #BlueSkyM arrives in #Italy: image via DW (English) @dw_english, 30 December 2014

The #BlueSkyM docked in Italian port of Gallipoli. Hundreds of migrants taken off ship overnight: image via James Reynolds @JamesEReynolds, 31 December 2014

UPDATE: #BlueSkyM had over 900 migrants from #Syria onboard. Smugglers abandoned the ship: photo by Reuters; image via Military Studies@ArmedResearch, 1 January 2015

Abandoned migrant ships -- approximate routes taken by the #Ezadeen and the #BlueSkyM: image via BBC News Graphcs @BBCNewsGraphics, 2 January 2015

2 Das Totenschiff

MT @FRANCE24 Migrant ‘ghost ship’ (most are from #Syria) arrives in Italian port: image via Charlotte @CharlotteSc, 3 January 2015

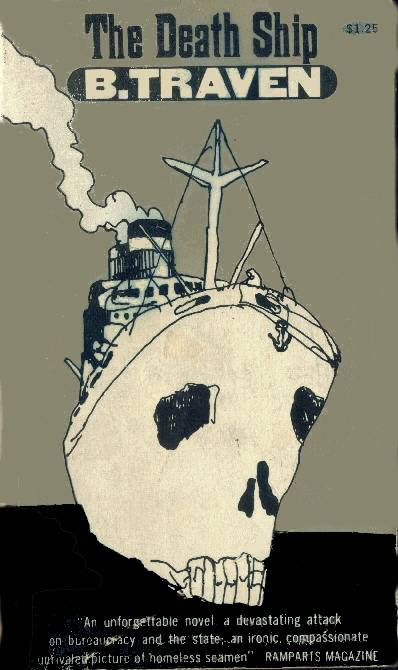

Das Totenschiff: Die Geschichte eines Amerikanischen Seemanns [The Death Ship): 1948 hardcover edition front wrapper

B. Traven: The Death Ship (U.S. paperback edition cover): image via Chrisopher Zisi @cjzisi, 23 September 2014

B. Traven: The Death Ship (U.S. paperback edition cover): image via Chrisopher Zisi @cjzisi, 23 September 2014

Publicity materials for the film Das Totenschiff [The Death Ship], 1959: from Illustrierte Film-Bühne vereinigt mit Illustr. Film-Kurier, Nr. 04975

(Gerd Heidemann Collection, UC Riverside Library)

Publicity materials for the film Das Totenschiff [The Death Ship], 1959: from Illustrierte Film-Bühne vereinigt mit Illustr. Film-Kurier, Nr. 04975

(Gerd Heidemann Collection, UC Riverside Library)

Le vaisseau des morts: Histoire d'un marin americain (Das Totenschiff / The Death Ship): Paris, 1974, cover: image via Ken Sanders Rare Books

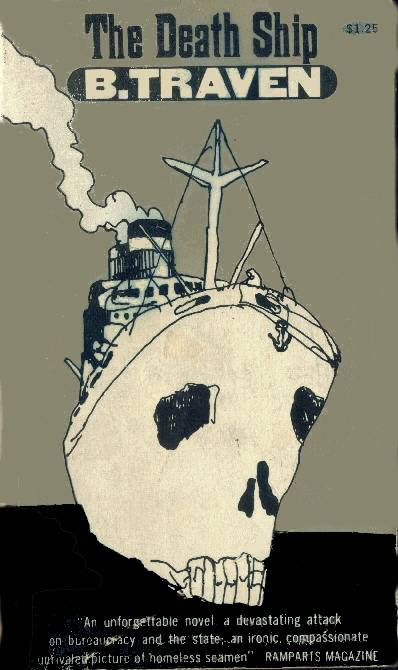

B. Traven: Das Totenschiff / Kapitel 4: artist unknown; image via ovguide

Bloodiest shower scene ever #Death Ship: image via Chrisopher Zisi @cjzisi, 23 September 2014

3 'We are alone'

'We are alone': Hundreds of Syrian migrants rescued off Italian coast #Ezadeen: image via Middle East Eye @MiddleEastEye, 2 January 2015

Migrants give thanks after 'ghost ship' Ezadeen rescued in Mediterranean:

Out of the hold of the Ezadeen, 360 Syrians emerged, towed to shore

after smugglers abandoned the controls

John Hooper in Corigliano, The Guardian, 3 January 2015

The man on crutches from Homs was in no doubt about the message he wanted to send to the world.

While he waited to be handed a bag of food and a bottle of water in

this southern Italian port, he turned to the handful of reporters left

on the quayside and shouted in a loud and resonant voice: “Italia –

good. Thank you, Italia. Thank you very much. All Italia … Good!”

Minutes before, he and 359 others had disembarked from the Ezadeen,

a Sierra Leone-registered livestock freighter. Police said on Saturday

that the number included 54 women, several pregnant, and 74 minors,

including eight who were unaccompanied.

As the Tyr –- the Icelandic coastguard patrol vessel that had towed

the ship to safety -– pulled it alongside the wharf, a restrained cheer

rippled from bow to stern of the Ezadeen.

Double lines of metal bars run either side of the battered old

freighter to prevent cattle and sheep from falling overboard. Those of

the Ezadeen’s human cargo who were still massed in the livestock hold

waved and grinned through the bars. If ever a moment captured the

indignities suffered by those who try to flee across the Mediterranean

to safety or a better life, this was it.

Icelandic military ship Landhelgisgaeslan escorts the Ezadeen, a 50-year-old livestock carrier, into port. The vessel docked at about 10pm on Friday: photo by Alfonso Di Vincenzo/AFP via The Guardian, 3 January

The first sign of the Ezadeen’s arrival had come more than an hour

earlier when the Tyr’s three masthead lights, signalling a long tow,

appeared beyond the mole that forms one half of the entrance to

Corigliano’s spacious harbour. The Icelandic vessel soon became a

dramatic sight – its engine exhaust smoke lit by a searchlight facing

aft and trailing behind it like a silvery pennant.

The Ezadeen had first been located on Thursday 40 nautical miles off

Cape Leuca, the very tip of the heel of the Italian boot, its crew

having relinquished control of the vessel in perilous seas. Whether they

left the ship is uncertain.

The

prefect of nearby Cosenza told reporters on Saturday that, according to

some of the migrants, the crew wore masks throughout the voyage. That

would have allowed them to mingle undisturbed with the people who

disembarked at Corigliano.

In an operation fraught with danger, an Italian air force helicopter

lowered six coastguards on to the deck of the Ezadeen so that they could

regain command of the vessel. But the ship had run out of fuel, and in

another risky exercise in high seas and icy winds, the crew of the Tyr

succeeded in attaching a line to the freighter.

The patrol vessel is part of Iceland’s contribution to Operation Triton,

mounted by the European Union’s border control agency, Frontex, at

Italy’s request. Though Iceland is not a member of the EU, it is a full

member of the Schengen area whose frontiers Frontex manages.

Most, if not all, of the Ezadeen’s “passengers” were from Syria.

Giovanna di Benedetto, a spokeswoman for Save the Children in Italy, who

arranged for an Arabic speaker to talk to the migrants, said: “They

left 10 days ago from Mersin in Turkey

and they remained about five days without food, without drink and they

told us that the crossing was very, very difficult and very, very

dangerous.”

The scene at the harbourside in Corigliano after the Ezadeen docked early on Saturday morning: photo by Francesco Arena/EPA via the Guardian, 3 January 2015

Mersin was also the port of departure indicated by several of those

queuing on the quayside. But the prefect said that at least some of the

migrants had flown from Lebanon to Turkey and departed from Antalya on

31 December.

Both accounts were consistent with tracking data that showed the

vessel moving westwards along the southern Turkish coast before heading

towards Greece and then on to Italy.

The arrival of the Ezadeen, and the earlier rescue of another freighter, the Blue Sky M,

carrying almost 800 Syrians, has dumped on Europe’s doorstep, more

resoundingly and awkwardly than ever before, the desperate human

consequences of the Arab spring.

Those in Europe

calling for curbs on immigration might cavil about the waves of

migrants reaching Italy’s southernmost islands from Libya and Tunisia.

Some do indeed come for a better life, rather than to escape death or

persecution. There are plenty of in-between cases: is a young man

fleeing military service for the dictatorship in Eritrea, for example,

truly a refugee?

But the man with the injured foot from Homs and others waiting by the

quayside in the early hours of Saturday would seem cut-and-dried cases.

Asked where they were from, one group of young men shouted “Kobani”.

Something else differentiated the Syrians on the Ezadeen from the

woebegone, mostly African migrants who reach Lampedusa and Pantelleria.

It is perhaps an odd epithet to use, but they looked distinctly

middle-class.

A couple of the women standing with their husbands on the ship,

watching it dock, might have been shopping in the nearest mall. A

pale-faced young woman in a knitted woolly hat with earmuffs and

drawstrings would not have looked out of place in a London or Paris

antiques market.

But then, and by their own accounts, in snatched conversations in the

port, the voyagers on the Ezadeen had spent $5,000 (£3,260) a head for

their passage. That is roughly three times the going rate for a place on

an inflatable dinghy for the even more dangerous crossing from north

Africa.

Accounts from the port of Gallipoli, further east, where the Syrians

on the Moldovan-registered Blue Sky M came ashore, spoke of engineers

and chemists. Several of those who left the Ezadeen admitted to being

students, but were reluctant to say more before they were hustled

towards the marquees erected by the emergency services.

A man waits as the Ezadeen docks in Corigliano: photo by Antonino D'Urso/AP via The Guardian, 3 January 2015

The reception of irregular migrants is a far bigger and more complex

operation than the TV images show. At the port in Corigliano, there were

half a dozen ambulances, several fire brigade vehicles, numerous police

cars, a lighting gantry, lines of tents, mobile offices and toilets,

Red Cross paramedics, civil protection volunteers, revenue guards,

semi-militarised carabinieri, police from three different forces,

harbour officials, doctors and nurses kitted out in overalls and masks,

naval officers and a priest. The cost must have run to thousands, if not

tens of thousands, of euros.

Italy

has performed a double U-turn in its policy towards seaborne

migration in the past four years. While the former prime minister Sivio

Berlusconi was still in power, migrants – including many deserving of

humanitarian

protection – were intercepted off the shores of Libya in particular and

returned to the tender mercies of the Gaddafi regime. Italy’s next

government put an end to this “push-back” approach, technically known as

refoulement, in 2012.

The following year, after more than 300 migrants died off Lampedusa

and Pope Francis made an impassioned appeal for tolerance, Rome launched Mare Nostrum,

a proactive search-and-rescue operation in which Italian naval vessels

hunted for migrants in distress up to the edge of Libyan territorial

waters.

The effects of Operation Mare Nostrum are highly contentious. It

coincided with an upsurge in the numbers of people reaching Italy by

sea. But was it the cause of the exodus, as Berlusconi’s followers and

his former supporters in Matteo Renzi's left-right coalition

maintain? Or did it just happen to be launched as numbers surged

because of the deteriorating security conditions in Libya and a pile-up

of refugees fleeing from Syria and Iraq?

Renzi’s interior minister, Angelino Alfano,

once Berlusconi’s justice minister, backed the first explanation and

began to phase out Mare Nostrum from 1 November. It has been replaced by

the EU’s Operation Triton, which has a budget less than a third of the

reported cost of Mare Nostrum, and a remit to ensure “effective border

control” in the Mediterranean, with “persons and vessels in distress” as

a secondary consideration.

This is the other significance of last week’s dramas on board the

Ezadeen and Blue Sky M: they have highlighted more starkly than before

the people-smugglers’ response to the latest change of policy. It is

pure moral blackmail. Frontex and the Italian authorities can either

take charge of the ship –- or responsibility for the deaths of hundreds

of people.

Inside the Ezadeen’s livestock hold, where the Syrian migrants travelled: photo by Alfonzo di Vincenzo/AFP via the Guardian, 3 January 2015

Admiral Giovanni Pettorino, the operational commander of the Italian coastguard, said this was “the

third case we have recorded in this last few weeks of a ship abandoned

to its fate with hundreds of people aboard”.

He said the traffickers used “merchant vessels at the end of their

life -– rust buckets bought for $100,000-$150,000 and then filled with

hundreds of ‘migrants’, mostly Syrians, who pay up to $6,000 each for

the crossing”. The Ezadeen would have brought in earnings of around

$1.8m.

So, as the admiral said, the smugglers “have no compunction in

abandoning the ship, given the profit margin”. He told news agency

Adnkronos that, if a way were not found to deal with the traffickers’

latest wheeze, the leaving of ships adrift in the Mediterranean would

create “a very serious problem for navigation”.

It has also created an excruciating conundrum for the Italian

authorities. Early on Saturday, police had been given instructions to

prevent journalists speaking to the new arrivals.

Unlike the Syrians on board the Blue Sky M, those who arrived in

Corigliano were bundled on to coaches to be driven to centres in other

parts of Italy. Local reception facilities, police said, were

overflowing.

Syrian migrants rescued from the drifting "ghost ship" Ezadeen. The International Organisation for Migration said such incidents took “the smuggling game to a whole new level”: photo by Stringer/Italy/Reuters via The Guardian, 3 January 2015

People-smugglers draw from large pool of merchant shipping workhorses:

The ‘ghost ship’ Ezadeen is a former livestock carrier that has had many

names since it first started operating in 1966

Ben Quinn, The Guardian, 2 January 2015

The so-called ghost ship carrying at least 450 migrants which was towed into an Italian port by coastguards on Friday after people-smugglers abandoned it off Europe's south coast was drawn from the large supply of often rusting hulks that have acted as workhorses in the merchant shipping industry over recent decades.

Records of the Ezadeen’s movements show that it left Tartus, Syria’s second largest port, in October before sailing north towards the southern coast of Turkey and looping back towards northern Cyprus. After leaving Famagusta, in northern Cyprus, on 19 December, it returned to the Turkish coast and repeatedly changed direction as if in a holding pattern between Cyprus and Turkey.

According to co-ordinates recorded by Vessel Finder, which provides software that tracks vessels using AIS (Automatic Identification System) signals, the Ezadeen then embarked on a fairly steady route over the last week and a half, skirting Turkey’s southern Mediterranean coast, passing north of Crete and then along the west coast of Greece. It is not clear at what point the bulk of the migrants were taken on board.

The Ezadeen is a former livestock carrier that has gone through at least seven changes of name since it first started operating as a cargo ship in 1966. Its most recent owner -– officially at least -– appears to have been a merchant marine company based in Lebanon, but somewhere along the way it seems people-smugglers took control of it.

Made in Germany, the 1,474-tonne vessel has been flying under the flag of Sierra Leone for the past four years and was previously under that of Syria. A sample of its docking history over the past year also reflects the disparate jurisdictions that such ships pass through. In March last year it was in the Romanian port of Midia, before later visiting Beirut, Dubai, Beirut again, Aden and the Egyptian ports of Suez and Port Said.

A previous “ghost ship”, the Blue Sky M, which was abandoned and believed to have been left on autopilot by people-smugglers, was carrying 970 people when t was intercepted this week. It is listed as a general cargo ship, sailing under a Moldovan flag. The BBC reported that the safety manager of a company hired to provide safety certification for the vessel said he had withdrawn its certificate several months ago after finding it unsafe.

A report by the International Maritime Organisation in 2011 estimated that around the world there were 100,000 sea-going merchant ships with at least a 100 gross tonnage. The average age was 22 years and they were registered across more than 150 countries.

[The Ezadeen off Crotone, near the heel of Italy] AUDIO: Who's on board these migrant boats and where are they coming from? #BlueSkyM #Ezadeen: image by Icelandic Coast Guard via BBC Outside Source @BBCOS, 2 January 2015

“We are alone and we have no one to help us”

Smugglers abandon ship

off Italy in new tactic to force rescue: Watchdog says smugglers

‘playing chicken with people’s lives’ after Ezadeen, carrying 450, found

adrift in dangerous seas

John Hooper in Rome, Patrick Kingsley in Cairo and Ben Quinn: The Observer, 2 January 2015

A “ghost ship” carrying hundreds of migrants was abandoned on Friday by its crew of smugglers in dangerous seas off the coast of southern Italy, in a move that a spokesman for the International Organisation for Migration said “takes the smuggling game to a whole new level”.

The cargo ship Ezadeen, which set sail under a Sierra Leone flag from a Turkish port this week, was discovered drifting without a captain 40 nautical miles from the Italian coast. Italian coastguards were forced to intervene to prevent a disaster and possibly save the lives of the estimated 450 people on board, many of them thought to be Syrian refugees.

“We are alone and we have no one to help us,” a migrant woman told officials by radio after the ship was asked to identify itself, coastguard spokesman Filippo Marini told an Italian radio station. Footage showed Italian officers landing on the Ezadeen by helicopter, before the ship was towed to Italy.

The Ezadeen was the second vessel in four days to be found sailing without a crew. Earlier in the week, 800 migrants on the Blue Sky M, a Moldovan-registered ship, were rescued by Italian coastguards when it was discovered sailing without an active crew five miles off the coast.

The two incidents have left observers of migrant routes in the Mediterranean fearing that people-smugglers have found a new and ruthless way of working in the area despite a recent decision to scale back Italian rescue operations.

“It’s an extraordinary way to treat people,” said Leonard Doyle, a spokesman for the IOM, a UN-linked body that focuses on migrants. “The abandonment of ships in the high seas is a very dangerous thing to do at the best of times and takes the smuggling game to a whole new level that we’ve never seen before.”

The tactic shows that despite the cancellation last autumn of Operation Mare Nostrum –- an Italian-run rescue scheme that European authorities feared was a prominent reason why migrants were risking all to reach Europe –- smugglers are still finding ways to get close to the Italian shore and force coastguards to rescue their passengers.

Under the new system, ships carrying illegal migrants are supposed to be intercepted by a pan-European maritime border agency and prevented from reaching Italian waters. But Doyle said smugglers were now presenting their ships as legal entities until they were within a few miles of Italy. Then they disembarked, forcing the Italian authorities to intervene in order to save lives.

“It’s almost as if [the smugglers] are playing chicken with the lives of vulnerable people -– men, women and children who are fleeing war –- and seeing who blinks first,” said Doyle.

“But they know full well that the Italian coastguards will have to intervene.”

Italian Red Cross volunteers assist. The EU has vowed to fight traffickers’ apparent new tactic of abandoning ships full of migrants off European coasts: photo by Alfonso Di Vincenzo/AFP via The Guardian, 3 January 2015

“They only have GPS,” said the ship owner, who asked to be known as Abu Khaled, from a port on Egypt’s north coast. “Someone else starts the motor for them -– and they follow the direction on the GPS device. So the driver doesn’t have any more sailing knowledge than this. He just follows the arrow. The GPS is the captain. If the waves become higher, they don’t know how to deal with it -– so they just keep on going.”

Some European politicians believe the answer is to create an even bigger deterrent than the cancellation of Mare Nostrum. Claude Moraes, a British MEP, told the BBC that its replacement scheme, Triton, “scares no one”, and he called for a new scheme that could be given the backing of a national judicial system.

But others believe that little will deter the hundreds of thousands of migrants seeking to escape war and hardship in the Middle East. “Why do we keep going by sea?” asked Ahmed, a Syrian arrested while attempting to cross the Mediterranean from Egypt this autumn. “Because we trust God’s mercy more than the mercy of people here.”

Doyle said it had been thought that the Mare Nostrum was “a pull factor, attracting migrants, and that by ending it migrants would stay on the other side of the Med. What we’re seeing is that whether or not there was a pull factor, people are still coming. There is still a demand from people who are desperately fleeing the Syrian war and who are looking for ways to be rescued and taken ashore safely.”

The recent activity of the stricken Ezadeen appears to shine a light on the demand for smuggling, even in the stormier winter months. Records show that the ship departed from Tartus, Syria’s second largest port, in October before sailing north towards Turkey. Then it sharply looped back south towards Cyprus.

After sailing towards the port of Famagusta, in northern Cyprus, it then sailed north once again towards the Turkey coast before zig-zagging in an area of open water between Turkey and Cyprus.

Over the past week and a half it skirted westwards along Turkey’s Mediterranean coast, according to records provided by Astra Paging, which provides software that tracks vessels using signals broadcast from vessels.

The ship continued in a western direction to the north of Crete, changed direction and heading northwards along the coast of Greece before ending up drifting across towards Italy, where it appears to have been abandoned.

Migrants on the deck as the ship docks in Italy. The vessel, which set sail from a Turkish port, was discovered drifting without a captain 40 nautical miles from the Italian coast: photo by Stringer/Italy/Reuters via The Guardian, 3 January 2015

Arab spring prompts biggest migrant wave since second world war:

Migrants fleeing the Middle East and north Africa are already risking

everything as they try to escape war at home:

Patrick Kingsley in Cairo, The Guardian, 3 January 2015

The two "ghost ships”

discovered sailing towards the Italian coast last week with hundreds of

migrants – but no crew – on board are just the latest symptom of what

experts consider to be the world’s largest wave of mass-migration since

the end of the second world war.

Wars in Syria, Libya and Iraq, severe repression in Eritrea, and spiralling instability across much of the Arab world have all contributed to the displacement of around 16.7 million refugees worldwide.

A further 33.3 million people are “internally displaced” within their own war-torn countries, forcing many of those originally from the Middle East to cross the lesser evil of the Mediterranean in increasingly dangerous ways, all in the distant hope of a better life in Europe.

“These numbers are unprecedented,” said Leonard Doyle, spokesman for the International Organisation for Migration. “In terms of refugees and migrants, nothing has been seen like this since world war two, and even then [the flow of migration] was in the opposite direction.”

European politicians believe they can discourage migrants from crossing the Mediterranean simply by reducing rescue operations. But refugees say that the scale of unrest in the Middle East, including in the countries in which they initially sought sanctuary, leaves them with no option but to take their chances at sea.

More than 45,000 migrants risked their lives crossing the Mediterranean to reach Italy and Malta in 2013, and 700 died doing so. The number of dead rose more than four times in 2014 to 3,224.

“We know people who died -– they used to live with us,” said Qassim, a Syrian refugee in Egypt who now wants to reach Europe. “But we will try again to cross the sea because there’s no life for us Syrians here.”

Men look out from on board. All of the migrants on board were believed to be from Syria: photo by Antonino D'Urso/AP via The Guardian, 3 January 2015

In

Egypt, up to 300,000 refugees from the Syrian war were initially

welcomed with open arms. But after Cairo’s sudden regime change in

summer 2013, the atmosphere turned drastically, leading to rampant

xenophobia against Syrians and increased arrests and detentions of those

who, for understandable reasons, did not carry the correct residency

paperwork.

The situation is even worse in Jordan and in Lebanon, which now houses more than 1 million Syrian refugees –- more than a fifth of the country’s total population.

Their presence has created an unprecedented strain on national resources, leading to the Lebanese government tightening restrictions last week on Syrians entering the country.

And while Turkey has simultaneously moved to strengthen refugees’ rights, Turkish shores are likely to remain a popular launch pad for migrants looking to reach Europe because of both the comparatively high cost of living, as well as rising xenophobia, particularly in the country’s south.

Libya, another major point on the migration route from the Middle East and north Africa, is also no longer a safe haven after a civil war erupted there last year. The plight of refugees there, as well as across the region, makes a mockery of those who suggest the wave of migration is caused simply by economic migrants.

“If they’re economic migrants,” asked Doyle, “then how do we explain that after every outbreak of violence and repression we get a new wave of people from the area that’s just had that outbreak? Why was it that, in the huge September disaster in the Mediterranean, the people who drowned were Palestinians, just a couple of weeks after the war between Gaza and Israel? And why is it that since last year there has been a steady flow of people from Eritrea, when we know there are serious problems in that country?”

But such arguments have yet to convince the British government, which refused last October to help Mediterranean rescue operations, and which by last June had admitted fewer than 150 Syrian refugees.

Wars in Syria, Libya and Iraq, severe repression in Eritrea, and spiralling instability across much of the Arab world have all contributed to the displacement of around 16.7 million refugees worldwide.

A further 33.3 million people are “internally displaced” within their own war-torn countries, forcing many of those originally from the Middle East to cross the lesser evil of the Mediterranean in increasingly dangerous ways, all in the distant hope of a better life in Europe.

“These numbers are unprecedented,” said Leonard Doyle, spokesman for the International Organisation for Migration. “In terms of refugees and migrants, nothing has been seen like this since world war two, and even then [the flow of migration] was in the opposite direction.”

European politicians believe they can discourage migrants from crossing the Mediterranean simply by reducing rescue operations. But refugees say that the scale of unrest in the Middle East, including in the countries in which they initially sought sanctuary, leaves them with no option but to take their chances at sea.

More than 45,000 migrants risked their lives crossing the Mediterranean to reach Italy and Malta in 2013, and 700 died doing so. The number of dead rose more than four times in 2014 to 3,224.

“We know people who died -– they used to live with us,” said Qassim, a Syrian refugee in Egypt who now wants to reach Europe. “But we will try again to cross the sea because there’s no life for us Syrians here.”

Men look out from on board. All of the migrants on board were believed to be from Syria: photo by Antonino D'Urso/AP via The Guardian, 3 January 2015

The situation is even worse in Jordan and in Lebanon, which now houses more than 1 million Syrian refugees –- more than a fifth of the country’s total population.

Their presence has created an unprecedented strain on national resources, leading to the Lebanese government tightening restrictions last week on Syrians entering the country.

And while Turkey has simultaneously moved to strengthen refugees’ rights, Turkish shores are likely to remain a popular launch pad for migrants looking to reach Europe because of both the comparatively high cost of living, as well as rising xenophobia, particularly in the country’s south.

Libya, another major point on the migration route from the Middle East and north Africa, is also no longer a safe haven after a civil war erupted there last year. The plight of refugees there, as well as across the region, makes a mockery of those who suggest the wave of migration is caused simply by economic migrants.

“If they’re economic migrants,” asked Doyle, “then how do we explain that after every outbreak of violence and repression we get a new wave of people from the area that’s just had that outbreak? Why was it that, in the huge September disaster in the Mediterranean, the people who drowned were Palestinians, just a couple of weeks after the war between Gaza and Israel? And why is it that since last year there has been a steady flow of people from Eritrea, when we know there are serious problems in that country?”

But such arguments have yet to convince the British government, which refused last October to help Mediterranean rescue operations, and which by last June had admitted fewer than 150 Syrian refugees.

A Syrian looks out from the ship. The Ezadeen was the second vessel in four days found sailing without a crew. Earlier in the week, 800 migrants on the Blue Sky M were rescued by Italian coastguards: photo by Alfonso Di Vincenzo/AFP via The Guardian, 3 January 2015

A boat filled with Palestinian and Syrian immigrants sank and immigrants drowned near Alexandria, #Egypt, reports of numerous Gazans dead: image via Dr Belal Dabour - Gaza @Belalmd12, 13 September 2014

4 The deadliest year

2014 deadliest year so far in #Syrian #conflict: image via DW (English) @dw_english, 1 January 2015

Over 76,000 people killed in #Syrian war in 2014 – NGO: image via Sputnik @Sputnikint, 1 January 2014

There are thousands of #Syrian displaced people suffering inside the country: Image via Mustafa Bag @mustafa__bag, 30 December 2014

rebels raining down shells on west Aleppo like

crazy, this one hit near Souria petrol station in Sliemanieyh #Syria:

image via Edward Dark @edwardedark, 30 December 2014

Pic via @TheSyriaPulse: Rebel fighter moves through wall near frontline against regime forces, #Aleppo #Syria Dec. 28: image via Al-Monitor @AlMonitor, 31 December 2014

This is the kind of selfies regime gangs (Shabiha) take in #Syria ...

"Selfie with the destruction of #Homs behind me": image via Haya Atassi @haya_atassi, 29 December 2014

76,021 people were killed in the #Syria conflict last year which started with protests & spiraled into a #CivilWar: image via Sattvika Khera @SatvikaKhera, 1 January 2015

#Syria war deadliest in 2014 with 76,000 killed: Monitor: image via News Nation @NewsNationTV, 1 January 2014

Syria's Assad promises jobs to relatives of killed soldiers #Syria: image via Middle East ye @MidleEastEye, 1 January 2015

Syrian conflict has claimed 76,000 lives in deadliest year yet, say monitors #Syria: image via MintPress News @MintPressNews, 1 January 2015

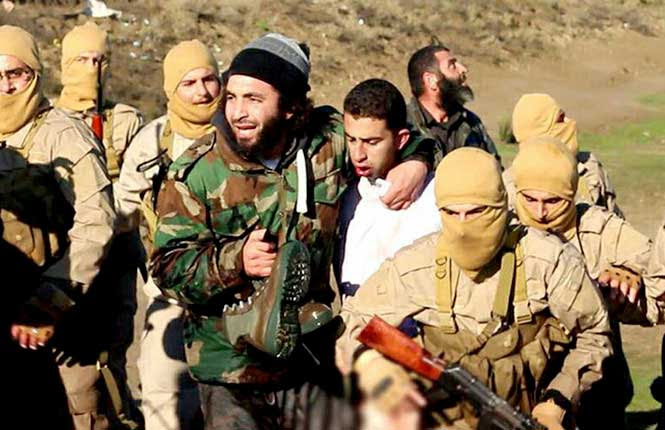

#ISIS executed nearly 2,000 people in #Syria, mostly civilians, in 6 months – monitor: image via RT America @RT_America, 29 December 2014

#ISIS captures Jordanian pilot after warplane crashes in #Syria: image via Hindustan Times @htTweets, 25 December 2014

A Free Syrian Army fighter

walks through a hole in the wall inside a damaged building on the

frontline of Aleppo’s Al-Ezaa neighbourhood: photo by Hosam Katan/Reuters via The Guardian, 1 November 2014

A Free Syrian Army fighter takes up position as he points his weapon

through a hole in a bedroom wall in Deir al-Zor, eastern Syria. A

reminder of ordinary daily life before the civil war: photo by Khalil

Ashawi / Reuters via The Guardian, 12 November 2013

Aleppo, Syria. Rebel fighters move a homemade weapon known as a ‘hell cannon’: photo by Karam Almasri / NurPhoto/ Rex via The Guardian, 4 December 2014

Aleppo, Syria. Rebel fighters move a homemade weapon known as a ‘hell cannon’: photo by Karam Almasri / NurPhoto/ Rex via The Guardian, 4 December 2014

A photograph taken from Suruc district of Sanliurfa, Turkey, near Turkish-Syrian border crossing shows smoke rising from the Syrian border town of Kobani: photo by Anadolu Agency via The Guardian, 1 January 2015

A man rests inside a house damaged by what activists said were air strikes by forces loyal to Syria’s president Bashar Al-Assad in Jabal al-Akrad area in northwestern Syria 31 December: photo by Alaa Khweled/Reuters via the Guardian, 4 January 2015

5 Flight

Thousands of migratory birds at Poyang lake in Jiujiang, Jiangxi province, China: photo by ChinaFotoPress via the Guardian, 2 January 2015

No comments:

Post a Comment