Meanwhile in Athens: A timeless allegory. That changes by the hour: image via Nein. @NeinQuarterly, 28 June 2015

The spider sees bliss

Approaching in the eye

Approaching in the eye

Of an immobile fly.

Vassilis Zambaras: Web from Vazambam, Sunday 28 June 2015

Vassilis Zambaras: Web from Vazambam, Sunday 28 June 2015

A young woman walks past a graffiti in Athens called 'Death of Euro': image via Aris Messinis @ArisMessinis, 19 June 2015

A woman walks past a wall painting in #Athens, Greece on June 24, 2015. #photo by @ArisMessinis: image via Agence France-Pressse @AFP, 24 June 2015

A woman stands in front of a graffiti bearing the number zero on a euro coin in central Athens: image via Aris Messinis @ArisMessinis, 27 June 2015

#Greece stands on the brink of bankruptcy's referendum: image via The Telegraph @Telegraph, 29 June 2015

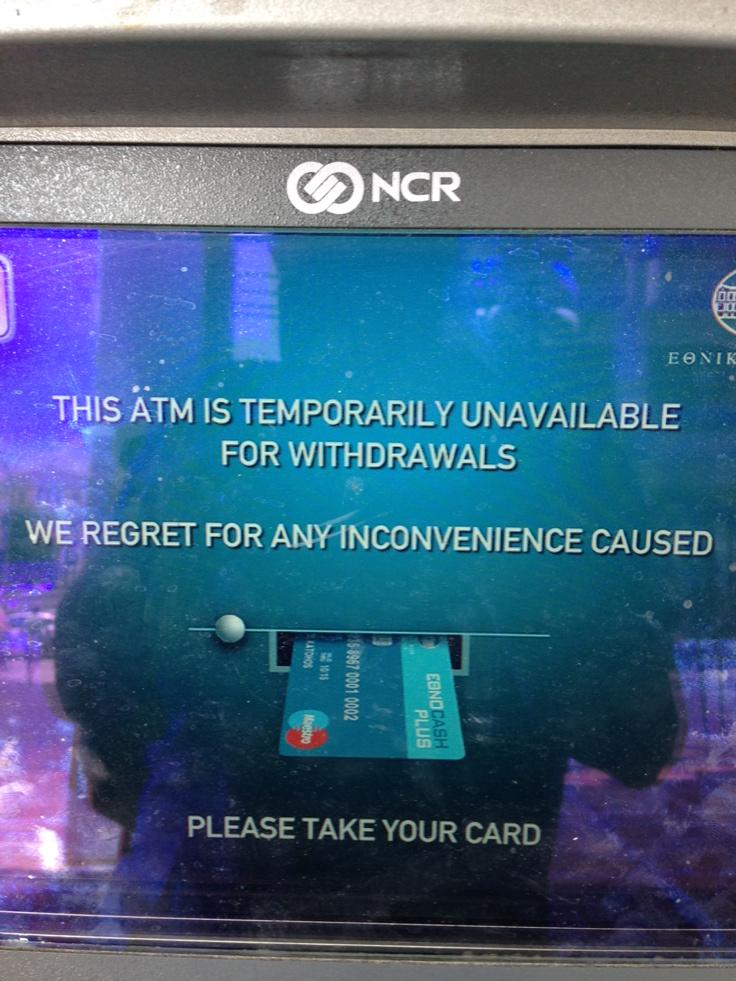

DETAILS: Limit daily cash withdrawals 60 euros, payments and transfers abroad banned #Greece: image via RT @RT_com, 29 June 2015

#GreeceCrisis Graffiti and people in the streets in Athens on June 28, 2015. #AFP PHOTO by @ArisMessinis: image via Aurelia BAILLY @Aurelia BAILLY, 28 June 2015

Anti-EU group gathers in Syntagma Square. Sign reads: No to the agreement, overthrow the EU and the IMF #athens: image via Katie Slaman @katieslaman, 28 June 2015

A man walks past a graffiti in Athens with a EU flag reading in German

"NO" concerning Greece's referendum: image via Aris Messinis @ArisMessinis, 28 June 2015

People line up to withdraw money from an ATM outside a branch of Greece's Alpha Bank in Athens on Sunday: photo by Alexandros Vlachos / European Pressphoto Agency via Los Angeles Times, 28 June 2015

Leftist youth hold a placard reading, "No more recession, out of the Eurozone," during a demonstration in Athens calling for Greece's exit from the Eurozone: photo by Louisa Gouliamaki / AFP via Los Angeles Times, 28 June 2015

Greek Finance Minister Yanis Varoufakis arrives at the Finance Ministry in Athens for a meeting of the Systemic Stability Council: photo by Simela Pantzartzi / European Pressphoto Agency via Los Angeles Times, 28 June 2015

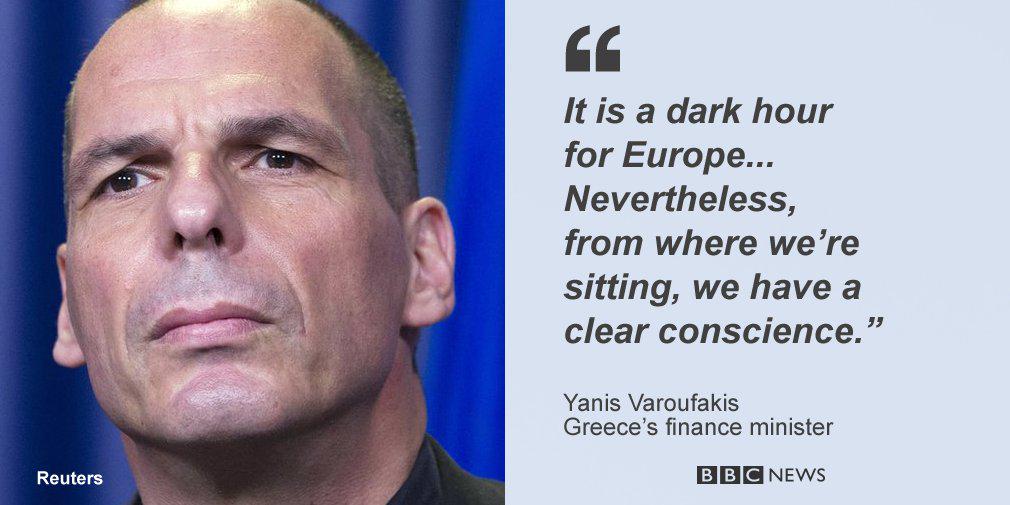

#Greece has "bent over backwards" on bailout deal but others "have not come to the party", finance minister tells BBC: image via BBC Breaking News @BBCBreaking, 28 June 2015

Graffiti around Athens as #Greece crisis escalates #photo by @atzortinis: image via Agence France-Presse @AFP, 28 June 2015

Graffiti around Athens as #Greece crisis escalates #photo by @arismessinis: image via Agence France-Presse @AFP, 28 June 2015

Graffiti around Athens as #Greece crisis escalates #photo by @arismessinis: image via Agence France-Presse @AFP, 28 June 2015

#GreeceCrisis Graffiti and people in the streets in Athens on June 28, 2015. #AFP PHOTO by @ArisMessinis: image via Aurelia BAILLY @Aurelia BAILLY, 28 June 2015

Banks in #Greece to stay closed on Monday = Sunday evening queue at the ATM ... Some anxious faces: image via jon henley @jonhenley, 28 June 2015

Banks in #Greece to stay closed on Monday = Sunday evening queue at the ATM ... Some anxious faces: image via jon henley @jonhenley, 28 June 2015

That's a shut bank ... #Greece: image via jon henley @jonhenley, 28 June 2015

A lot of these around this morning ... #Greece: image via jon henley @jonhenley, 28 June 2015

Theodor W. Adorno: from 'The Position of the Narrator in the Contemporary Novel', in Notes to Literature: Volume One, ed. Rolf Tiedemann, 1991

#digilit15 Thomas Ernst zitiert Adorno (Standort des Erzählers): image via Philippe Wampfler @phwampfler, 26 June 2015

@NeinQuarterly Are you already in Greece? [photo by Aris Messinis / AFP]: image via Micha Hartsch @michahartsch, 28 June 2015

@NeinQuarterly Are you already in Greece? [photo by Aris Messinis/AFP]: image via Micha Hartsch @michahartsch, 28 June 2015

Is this normal for Athens? Busload of troops w/ assault rifles outside my hotel, apparently guarding govt buildings: image via Simon Shuster @shustry, 28 June 2015

A sad spectacle in Athens: image via Stathis Kalyvas @SKalyvas, 28 June 2015

Greek banks to shut for several days and limit withdrawals from cash machines: image via independent,ie @independent, ie, 28 June 2015

Some ATMs in #Athens empty after ECB retains emergency funding limit: image via Ruptly @Ruptly, 28 June 2015

Cut the debt #IMF go home graffiti in #Athens: image via Lizzie Phelan @LizziePhelan, 28 June 2015

Greek media showing pictures of long lines at ATMs. People in coats and scarves. It was 30° in Athens. SHAME ON YOU.: image via Alex Andreou @sturdyAlex, 28 June 2015

Georgios Karvouniaris and his sister Barbara outside their donated caravan, without which they would be homeless: photo by Jon Henley for The Guardian, 28 June 2015

The Greeks for whom all the talk means nothing –- because they have nothing: For Georgios Karvouniaris, his sister Barbara, and

many thousands like them, whether Greece stays in the eurozone or not is

unlikely to have any effect: Jon Henley in Athens for The Guardian, 28 June 2015 (updated 29 June 2015)

On a steep, gardenia-scented street in the north-eastern Athens

suburb of Gerakas, in one corner of a patch of bare ground, stands a

small caravan.

Plastic mesh fencing –- orange, of the kind builders use –- encloses a

neat garden in which peppers, courgettes, lettuces and beans grow in

well-tended raised beds. Flowers, too.

The caravan is old, but spotless. It is home to Georgios

Karvouniaris, 61, and his sister Barbara, 64, two Greeks for whom all

the Brussels wrangling over VAT rates, corporation tax and pension

reforms has meant nothing -- because they have nothing, no income of any

kind.

Next Sunday’s referendum -- which, if the country stays solvent that long, will either send Greece

back to the negotiating table with its creditors or precipitate its

exit from the eurozone -- is unlikely to affect them much either.

“I do not see how any of it will change our lives. I have no hope,

anyway,” said Georgios, sitting in a scavenged plastic garden chair

beneath a parasol liberated from a skip.

After seven years of a crisis that has left 26% of Greece’s workforce

unemployed, 30% of its people below the poverty line, 17% unable to

meet their daily food needs and 3.1 million without health insurance, it

is hard to see how anything decided in Brussels or in Athens in the

coming week will do much to change the lives of a large number of Greeks

any time soon.

“Those that were already on the margins have been pushed right to the

very, very edge, and those who were in the middle have been pushed to

the margins,” said Ioanna Pertsinidou of Praksis, a charity that runs

day centres for vulnerable people and offers legal and employment

advice.

“So

many people – ordinary, low-to-middle income people with jobs and homes

and their lives on track -- have seen their lives go drown the drain so

fast,” Pertsinidou said. “People who never dreamed that one day they

would not be able to pay their electricity bill, or feed their children

properly.”

As it has scrabbled for every last cent to satisfy its creditors and

ward off bankruptcy, Greece’s government has taken cash wherever it

could -- local authorities, healthcare, pensions, social services have

all been tapped. In a country of 11 million people, public spending is

now €65bn (£45.6bn) less than it was in 2010. “There is no safety net

left,” said Pertsinidou.

No one need tell that to the Karvouniaris family. Georgios is a stern

man, still strong, smartly shaven and dressed in a clean green polo

short and jeans. His sister, remarkably jovial, wears black for their

younger brother Vangelis, who died of nobody will say exactly what two

years ago next month, aged 52. He spent a brief week in hospital before

his death, for which his siblings recently received a €2,000 bill --

which they managed to get written off.

Until March 2013, the three lived in an apartment a mile or so away

that they had shared since 1980. None of them had ever married. It

worked well. Georgios, a welder and mechanic before becoming a bank

security guard, and Vangelis, a salesman, shoe repairer and, latterly,

gardener, were the breadwinners. Barbara cooked, cleaned and looked

after her brothers.

Quite early in Greece’s crisis, Vangelis lost his job. Then in

February 2011, Georgios lost his at the Agrotiki bank, where he had

worked for 12 years. After leaving school at 12 and working ever since,

Georgios got €465 unemployment benefit for eight months, then €200 for a

year, then nothing.

The rent on the apartment was €250. “We spent all we had,” he said.

“Our savings. We sold Barbara’s jewellery, for half its worth. We tried

to sell this patch of land but no one would buy it. For the first time

in 30 years, we didn’t pay our rent. By the end we couldn’t even afford

food.”

If the Karvouniarises are not now sleeping rough, it is because a

neighbour saw them sitting in tears outside their apartment building,

formally threatened with eviction and all packed up but with nowhere to

go. They had not eaten for three days.

It took time, but Despina Moragianis -- a relative of that neighbour --

and her friends, Ann Papastavrou and Niki Festas, women in their 60s,

rallied their women’s group in Halandri.

Twenty-odd people, none wealthy, pitched in to buy the 15-year-old

caravan, which was towed to the Kourvaniaris family’s small plot, once

intended as Barbara’s dowry.

For 13 months there was no water, but a campaign by the women

persuaded the Gerakas town hall to fit a standpipe in May last year.

Later, the group raised €1,000 to have it plumbed into the caravan and a

septic tank dug, so the toilet works. The next target is a solar panel

for electricity.

Georgios Karvouniaris and his sister Barbara outside their caravan: photo by Jon Henley for The Guardian, 28 June 2015

Every month the group holds a raffle, the proceeds of which buy fresh

fruit and vegetables -- apples, oranges, beans, potatoes -- which

Moragianis and her friends bring up to the caravan once a week. Fresh

meat is once a week. Non-perishables -- spaghetti, rice, flour, condensed

milk, tomato sauce -- come from the food bank.

And so the Karvouniaris siblings survive. Georgios digs, recycles

what he can find on the streets, takes long walks and dreams of fresh

milk. No electricity means no fridge. Barbara cooks – there is a gas

stove – cleans, washes clothes and tends her garden.

The couple have no money -- a friendly town hall official paid their

latest €18 water bill out of his own pocket -- and no hope of any until

Georgios qualifies for his pension at 67. “I’d hoped it might be 65, in

four years’ time, but they’ve just recently decided to raise the age

limit,” he said.

He is not sure how much he will get even then. Pensions have been a

major stumbling block in Greece’s aid-for-reforms talks with its

creditors, who want further savings from a system whose benefits have

already been cut by 45%, leaving nearly half of Greece’s pensioners

below the monthly poverty threshold of €665.

It is not just pensioners in penury. Under a limited relief programme

promised by the Syriza party during its election victory in January,

more than 300,000 of the poorest Greek households applied last month for

food aid, a small rent allowance and to have their electricity

reconnected for free.

So far the government has found the money to pay a small housing

benefit to precisely 1,073 people, the social solidarity minister,

Theano Fotiou, admitted. The €70 a month grocery voucher Georgios and

Barbara were promised under the scheme -- “We have no house and no power,

so there was nothing else we qualified for,” said Georgios -- has yet to

materialise.

Barbara’s face briefly clouds. How does she feel about the way they

have been treated? “Disgusted,” she said, quietly. “Just … disgusted.”

She smiles again. “But we’ve been lucky. There are people who have

nowhere to sleep at all.”

According to a University of Crete study earlier this year, there are

now 17,700 people without proper and secure housing in Athens alone.

Some sleep rough or in cars, others camp with friends or relatives, or

live in squats and hostels.

A majority are in their own homes, threatened with imminent eviction

because they are among the estimated 320,000 Greek families who have

fallen behind with a mortgage or other payment to their bank.

Two are in a small donated caravan, living on food donated by a group

of Greek women. Georgios is grateful, but he also gets angry sometimes.

“I have worked all my life. I’ve paid my taxes all my life,” he said.

“I’m 61 years old and if it wasn’t for the generosity of people who

three years ago we had never met, we would be sleeping on a bench. You

do what you can. But it doesn’t seem right.”

#GreeceCrisis Graffiti and people in the streets in Athens on June 28, 2015. #AFP PHOTO by @ArisMessinis: image via Aurelia BAILLY @Aurelia BAILLY, 28 June 2015

5 comments:

The moral crusade against Greece must be opposed. The idea that Greece partly deserves its fate reflects an order in which wealth trumps democracy. We should fight a narrative that enfeebles us all: Zoe Williams, The Guardian, 28 June 2015:

"‘This is our political alternative to neoliberalism and to the neoliberal process of European integration: democracy, more democracy and even deeper democracy,' said Alexis Tsipras on 18 January 2014 in a debate organised by the Dutch Socialist party in Amersfoort. Now the moment of deepest democracy looms, as the Greek people go to the polls on Sunday to vote for or against the next round of austerity.

"Unfortunately, Sunday’s choice will be between endless austerity and immediate chaos. As comfortable as it is to argue from the sidelines that maybe Grexit in the medium term won’t hurt as much as 30 years’ drag on GDP from swingeing repayments, no sane person wants either. The vision that Syriza swept to power on was that if you spoke truth to the troika plainly and in broad daylight, they would have to acknowledge that austerity was suffocating Greece.

"They have acknowledged no such thing. Whatever else one could say about the handling of the crisis, and whatever becomes of the euro, Sunday will be the moment that unstoppable democracy meets immovable supra-democracy. The Eurogroup has already won: the Greek people can vote any way they like – but what they want, they cannot have.

"On Saturday the Eurogroup broke with its tradition of unanimity, issuing a petulant statement 'supported by all members except the Greek member'. Yanis Varoufakis, the Greek finance minister, sought legal advice on whether the group was allowed to exclude him, and received the extraordinary reply: 'The Eurogroup is an informal group. Thus it is not bound by treaties or written regulations. While unanimity is conventionally adhered to, the Eurogroup president is not bound to explicit rules.' Or, to put it another way: 'We never had any accountability in the first place, sucker.'

"More striking still is this line of the statement: 'The Eurogroup has been open until the very last moment to further support the Greek people through a continued growth-oriented programme.' The measures enforced by the troika have created an economic contraction akin to that caused by war. With unemployment at 25% and youth unemployment at nearly half, 40% of children now live below the poverty line. The latest offer to Greece promises more of the same. The idea that any of this is oriented towards growth is demonstrably false. The Eurogroup president, Jeroen Dijsselbloem, has started to assert that black is white.

"And that brings us to the crux of the troika’s programme: what is the point of reducing this country to rubble? The stated intention at the start of the austerity package was to restore order: allow Greece to take a short hit to its GDP in the interests of building a stronger, more balanced economy in the long run. As it became clear that growth was not restored and that even on its own terms – the creditor must come first – the plan was failing, the line changed. It became a moral crusade, a collective punishment of the Greeks."

[Zoe Williams continues:]

"In 2012 the head of the IMF, Christine Lagarde, said in an interview with this newspaper, 'Do you know what? As far as Athens is concerned, I also think about all those people who are trying to escape tax all the time. All these people in Greece who are trying to escape tax. And I think they should also help themselves collectively.' How? 'By all paying their tax.' At the time, it sounded strange: how, in a country of cripplingly high unemployment, with whole families living off the depleted income of one pensioner, was the answer going to come from tax?

"She was offering not a solution but a narrative: the Greeks were in this situation because they were bad people. They wanted a beneficent state, but they didn’t want to pool their resources to create one. The IMF was merely the instrument of a discipline they dearly needed. This line has broadly held – the debtors are presented as morally weaker than the creditors. To give them any concessions would be to reward their laziness and selfishness. The fact that debt is a two-way street – that the returns on debt exist because of the risk that the money might be lost, and creditors have their own moral duty to accept losses when they arise – is erased by this telling of the events.

"Also airbrushed out of that story is what the late economist Wynne Godley called (in 1992!) the 'lacuna in the Maastricht programme': that while its single-currency proposal made provision for a central bank, it had nothing to say on the matter of what would replace the democratic institutions – the national governments whose power, once they had no control over their own currency, would be limited. Now we have our answer: the strongest takes control. At the moment, Germany knows best. How do we know they know best? Because they are the richest. The euro was founded on the idea that the control of currency was apolitical. It has destroyed that myth, and taken democracy down with it.

"These talks did not fail by accident. The Greeks have to be humiliated, because the alternative – of treating them as equal parties or 'adults', as Lagarde wished them to be – would lead to a debate about the Eurogroup: what its foundations are, what accountability would look like, and what its democratic levers are – if indeed it has any. Solidarity with Greece means everyone, in and outside the single currency, forcing this conversation: the country is being sacrificed to maintain a set of delusions that enfeebles us all."

Tom, here's Stiglitz:

http://www.theguardian.com/business/2015/jun/29/joseph-stiglitz-how-i-would-vote-in-the-greek-referendum

Makes you think about how the IMF/World Bank have been f*ing over(if you pardon my French)lots of poor countries all these years.

From the Nobel economist Stiglitz (Billoo's extremely pertinent link):

___

Joseph Stiglitz: how I would vote in the Greek referendum

Neither alternative – approval or rejection of the troika’s terms – will be easy, and both carry huge risks

The Guardian, Monday 29 June 2015

"The rising crescendo of bickering and acrimony within Europe might seem to outsiders to be the inevitable result of the bitter endgame playing out between Greece and its creditors. In fact, European leaders are finally beginning to reveal the true nature of the ongoing debt dispute, and the answer is not pleasant: it is about power and democracy much more than money and economics.

"Of course, the economics behind the programme that the “troika” (the European Commission, the European Central Bank, and the International Monetary Fund) foisted on Greece five years ago has been abysmal, resulting in a 25% decline in the country’s GDP. I can think of no depression, ever, that has been so deliberate and had such catastrophic consequences: Greece’s rate of youth unemployment, for example, now exceeds 60%.

"It is startling that the troika has refused to accept responsibility for any of this or admit how bad its forecasts and models have been. But what is even more surprising is that Europe’s leaders have not even learned. The troika is still demanding that Greece achieve a primary budget surplus (excluding interest payments) of 3.5% of GDP by 2018.

"Economists around the world have condemned that target as punitive, because aiming for it will inevitably result in a deeper downturn. Indeed, even if Greece’s debt is restructured beyond anything imaginable, the country will remain in depression if voters there commit to the troika’s target in the snap referendum to be held this weekend.

"In terms of transforming a large primary deficit into a surplus, few countries have accomplished anything like what the Greeks have achieved in the last five years. And, though the cost in terms of human suffering has been extremely high, the Greek government’s recent proposals went a long way toward meeting its creditors’ demands.

"We should be clear: almost none of the huge amount of money loaned to Greece has actually gone there. It has gone to pay out private-sector creditors – including German and French banks. Greece has gotten but a pittance, but it has paid a high price to preserve these countries’ banking systems. The IMF and the other “official” creditors do not need the money that is being demanded. Under a business-as-usual scenario, the money received would most likely just be lent out again to Greece.

"But, again, it’s not about the money. It’s about using “deadlines” to force Greece to knuckle under, and to accept the unacceptable – not only austerity measures, but other regressive and punitive policies.

"But why would Europe do this? Why are European Union leaders resisting the referendum and refusing even to extend by a few days the June 30 deadline for Greece’s next payment to the IMF? Isn’t Europe all about democracy?"

[Stiglitz continues:]

"In January, Greece’s citizens voted for a government committed to ending austerity. If the government were simply fulfilling its campaign promises, it would already have rejected the proposal. But it wanted to give Greeks a chance to weigh in on this issue, so critical for their country’s future wellbeing.

"That concern for popular legitimacy is incompatible with the politics of the eurozone, which was never a very democratic project. Most of its members’ governments did not seek their people’s approval to turn over their monetary sovereignty to the ECB. When Sweden’s did, Swedes said no. They understood that unemployment would rise if the country’s monetary policy were set by a central bank that focused single-mindedly on inflation (and also that there would be insufficient attention to financial stability). The economy would suffer, because the economic model underlying the eurozone was predicated on power relationships that disadvantaged workers.

"And, sure enough, what we are seeing now, 16 years after the eurozone institutionalised those relationships, is the antithesis of democracy: many European leaders want to see the end of prime minister Alexis Tsipras’ leftist government. After all, it is extremely inconvenient to have in Greece a government that is so opposed to the types of policies that have done so much to increase inequality in so many advanced countries, and that is so committed to curbing the unbridled power of wealth. They seem to believe that they can eventually bring down the Greek government by bullying it into accepting an agreement that contravenes its mandate.

"It is hard to advise Greeks how to vote on 5 July. Neither alternative – approval or rejection of the troika’s terms – will be easy, and both carry huge risks. A yes vote would mean depression almost without end. Perhaps a depleted country – one that has sold off all of its assets, and whose bright young people have emigrated – might finally get debt forgiveness; perhaps, having shrivelled into a middle-income economy, Greece might finally be able to get assistance from the World Bank. All of this might happen in the next decade, or perhaps in the decade after that.

"By contrast, a no vote would at least open the possibility that Greece, with its strong democratic tradition, might grasp its destiny in its own hands. Greeks might gain the opportunity to shape a future that, though perhaps not as prosperous as the past, is far more hopeful than the unconscionable torture of the present.

"I know how I would vote."

Post a Comment