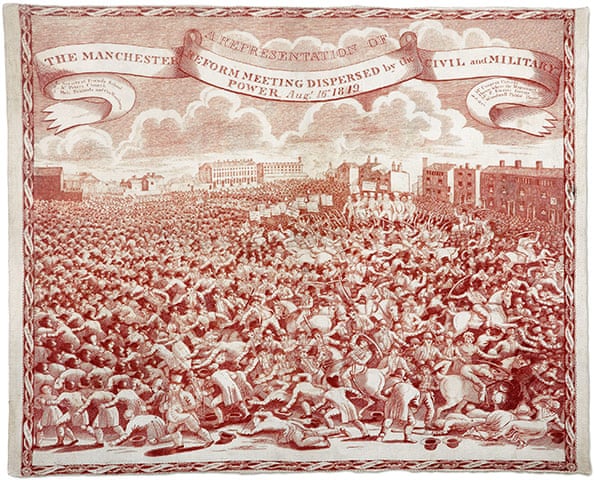

The Peterloo Massacre (forcible dispersal of a reform meeting in St Peter's Fields, Manchester). On August 16 1819, the day now

known as the Peterloo Massacre, thousands of peaceful protestors for

parliamentary reform had gathered at St Peter’s Square, Manchester. Ten

to twenty were killed and hundreds injured as the meeting was violently

broken up by the Manchester Yeomanry, a force of volunteer soldiers.

This vividly coloured print is one of several commemorative items

produced in the aftermath of the event: colour print, anonymous, London, 1819 (UK National Archives / British Library)

Percy Bysshe Shelley: England in 1819

An old, mad, blind, despised, and dying King;

Princes, the dregs of their dull race, who flow

Through public scorn, -- mud from a muddy spring;

Rulers who neither see nor feel nor know,

But leechlike to their fainting country cling

Till they drop, blind in blood, without a blow.

A people starved and stabbed in th' untilled field;

An army, whom liberticide and prey

Makes as a two-edged sword to all who wield;

Golden and sanguine laws which tempt and slay;

Religion Christless, Godless -- a book sealed;

A senate, Time’s worst statute, unrepealed --

Are graves from which a glorious Phantom may

Burst, to illumine our tempestuous day.

Percy Bysshe Shelley (1792-1822): England in 1819, 1819

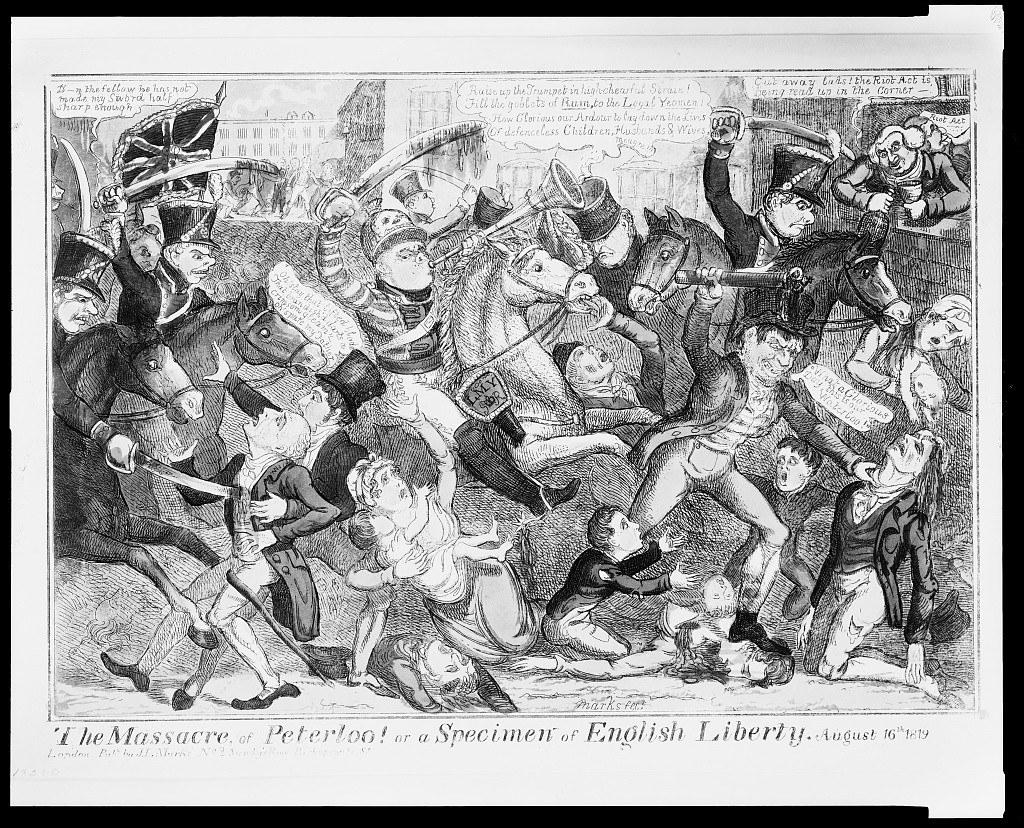

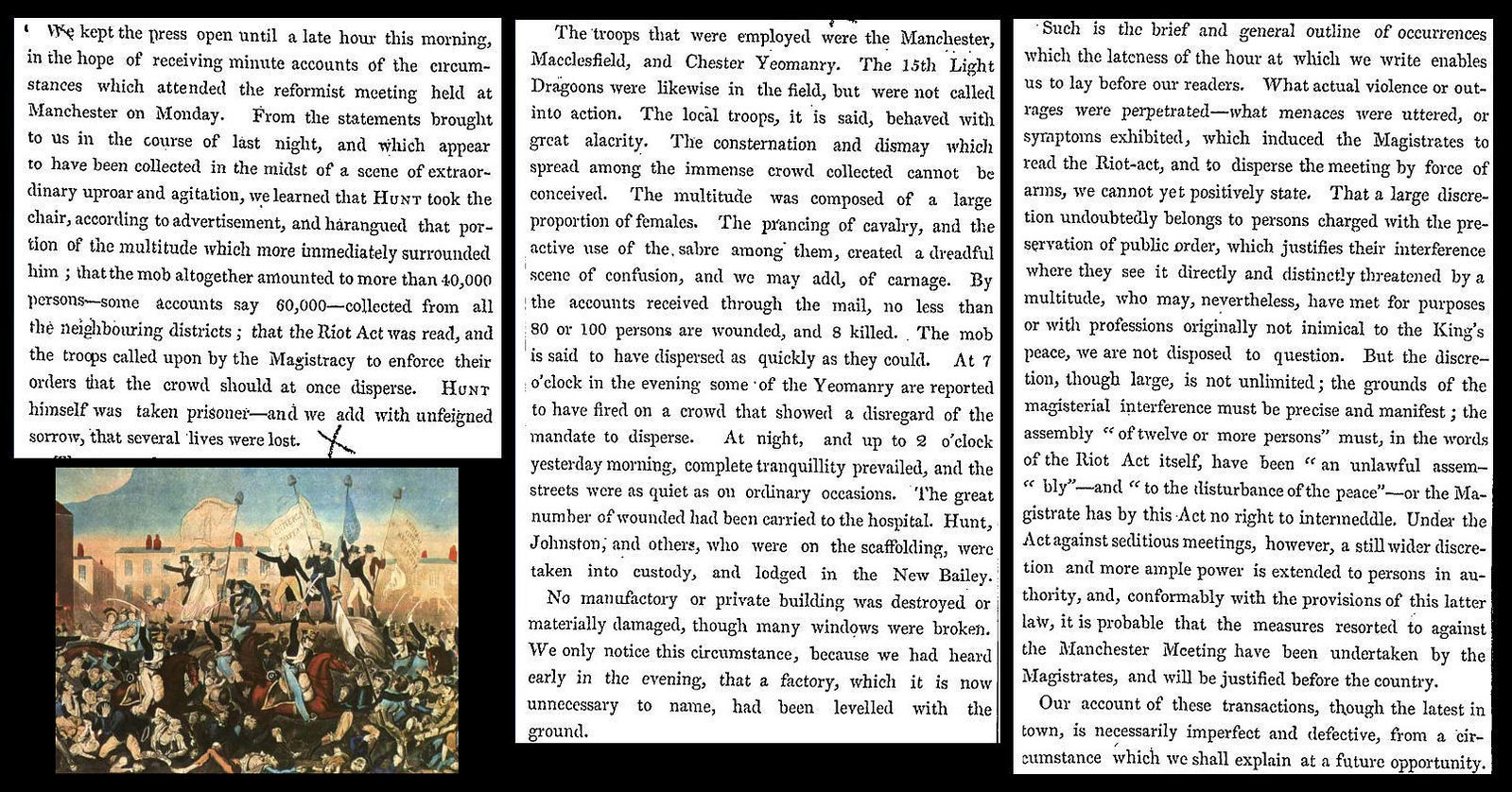

The Massacre of Peterloo! or a Specimen of English Liberty. Print showing the Manchester Yeomanry slashing and beating a crowd

gathered to demand parliamentary reform as the Riot Act is read from a

window.: artist unknown, 1819, etching and aquatint, 25.9 x 36.4 cm (British Cartoon Prints Collection, Library of Congress)

Heathcote Williams: For Shelley on the 4th August, His Birthday

“Poetry sees the starlight smile of children”Shelley said, seeing this as life’s truest wealth.

In Shelley’s world the “natural order

Has no place for tyrants” --

Neutering the beauty of the earth,

With all its inspirational beings:

Plants, animals, humans,

And elemental presences.

He was an atheist

Of a most particular kind

For his own spirit is ever present

In the poetry that he envisioned

To be “the interpenetration

“Of a diviner nature

“Through our own.”

He saw this poetry’s footsteps as being like

“Those of the wind over the sea

“Which the coming calm erases,

“And whose traces remain

“In the wrinkled sand which paves it.”

In just such a fashion Shelley’s now etched

Into the wrinkled neurology of the brain,

And he’ll rise to the surface in a trice

As the oppressed take up his chant:

‘We are many, they are few.’

These potent phrases were coined by him

After the Peterloo massacre where

Crowds of Manchester demonstrators

Protesting against cruel and unfair conditions

Were cut down by a Tory government --

Women and children included.

‘We are many, they are few’

Those who’ve never heard of Shelley

Know this to be true…

True for the Ninety Nine Percent who occupied Wall Street

To shame the One percent

Counting their algorithmic wealth In that cold-hearted gully;

True for those in Tahrir Square

At the height of the Arab Spring

Who adopted this as their slogan;

True for the two million who marched

Against the impending war in Iraq

With Shelley’s line displayed upon their banners.

Here’s how Byron invoked his dead friend

As he stood beside Shelley’s drowned body,

On the shores of Lerici on the Ligurian coast,

To watch its twenty-nine-year-old flesh burning:

“He was the most gentle, the most amiable,

“And least worldly minded person

“I ever met. Disinterested beyond all other men.

“And possessing a degree of genius

“Joined to simplicity

“As rare as it is admirable.

“He had formed to himself

“A beau-ideal

“Of all that is fine, high-minded and noble.

“He acted up to this ideal to the very letter.”

Shelley devised formulae for man’s improvement:

Poetic equations to enlighten those

Weighed down by enervating shibboleths.

He saw how, “The great man’s comfort equals the poor man’s woe”,

And how war makes small men feel important,

And why militarized violence is quite worthless

Because, “Man has no right to kill his brother.

“It is no excuse that he does so in uniform:

“He only adds the infamy of servitude to the crime of murder.”

Whilst laws passed in Shelley’s day are now redundant --

Consigned to unconsulted vellum scrolls --

And whilst the authorities who then held sway

Are no more than corpse-dust in the wind,

Shelley’s spirit is still legislating

For another world that’s possible.

“Government is an evil…” Shelley proclaims,

“When all men are good and wise,

“Government will of itself decay.”

He then whispers an erotic conjuration:

“Soul meets soul on lovers’ lips”,

As this life-lover dances through the aether.

Heathcote Williams: For Shelley on the 4th August, His Birthday via International Times, 4 August 2016

The Funeral of Shelley: Louis Édouard Fournier, 1889 (Walker Art Gallery, Liverpool)

The unconsummated sacrifice

The wind was wrong, the idea was silly, no one knew what they were doing

A greenish light glowered from the flat darkening sea

City workers cross the Millennium Bridge over the River Thames on a foggy morning in London: photo by Toby Melville/Reuters, 2 November 2015

City workers cross the Millennium Bridge over the River Thames on a foggy morning in London: photo by Toby Melville/Reuters, 2 November 2015

A seagull flies past Westminster Bridge during a foggy day in central

London today. Airports across Britain suffered disruption on Monday as

heavy fog led to delays and cancellations for a second day. Flights to

and from London airports were being affected, while foggy conditions in

the capital and across Europe were causing problems to airports around

the country: photo by Stefan Wermuth/Reuters, 2 November 2015

A seagull flies past Westminster Bridge during a foggy day in central London today. Airports across Britain suffered disruption on Monday as heavy fog led to delays and cancellations for a second day. Flights to and from London airports were being affected, while foggy conditions in the capital and across Europe were causing problems to airports around the country: photo by Stefan Wermuth/Reuters, 2 November 2015

Violence as anti-capitalist "Million Mask March" hits London: image via Agence France-Presse, 5 November 2015

Percy Bysshe Shelley: illustration by Culture Club, 2015

Protesters clash with police at anti-government #MillionMaskMarch demo: image via BBC News verified account @BBCNews, 2 November 2015

Percy Bysshe Shelley: image via Oxford University, 2015

Remember, remember the 5th of November. Guy Fawkes night.: image via Reuters Top News @Reuters, 5 November 2015

Violence as anti-capitalist "Million Mask March" hits London: image via Agence France-Presse, 5 November 2015

Protesters clash with police at anti-government #MillionMaskMarch demo: image via BBC News verified account @BBCNews, 25 November 2015

Noticed on why home from #MillionMaskMarch. Seems apt.: image via Damien Gayle @damiengayle, 5 November 2015

Violence as anti-capitalist "Million Mask March" hits London: image via Agence France-Presse, 5 November 2015

Protesters clash with police at anti-government #MillionMaskMarch demo: image via BBC News verified account @BBCNews, 25 November 2015

Noticed on why home from #MillionMaskMarch. Seems apt.: image via Damien Gayle @damiengayle, 5 November 2015

Violence as anti-capitalist "Million Mask March" hits London: image via Agence France-Presse, 5 November 2015

UK - Queen Elizabeth II, Prince Philip and Prince Charles attend the annual Braemar Gathering. By @acbphoto #AFP: image via Frédérique Geffard @fgeffard, 6 September 2015

Good morning. Yesterday The Queen attended the 200th #Braemar gathering. I use to also enjoyed attending the games: image via The Royal Butler @TheRoyalButler, 6 September 2015

Queen Elizabeth II greets

actor Angelina Jolie to present her with the insignia of an Honorary

Dame Grand Cross of the Most Distinguished Order of St Michael and St

George, in the 1844 room at Buckingham Palace, London: photo by Anthony Devlin / PA , 11 October 2014

Queen Elizabeth II greets actor Angelina Jolie to present her with the insignia of an Honorary Dame Grand Cross of the Most Distinguished Order of St Michael and St George, in the 1844 room at Buckingham Palace, London: photo by Anthony Devlin / PA, 11 October 2014

To Henry Hunt, Esqr. as chairman of the meeting assembled on St. Peter's Field, Manchester on the 16th. of August, 1819. On August 16 1819, the day now known as the Peterloo Massacre, thousands of peaceful protestors for parliamentary reform gathered at St Peter’s Square, Manchester. Ten to twenty were killed and hundreds injured as the meeting was violently broken up by the Manchester Yeomanry, a force of volunteer soldiers. This print is one of several commemorative items produced in the aftermath of the event. It describes the Yeomanry as a 'brutal armed force' who carried out 'a wanton and furious attack' on the protestors.: print, anonymous, 1819 (The British Museum)

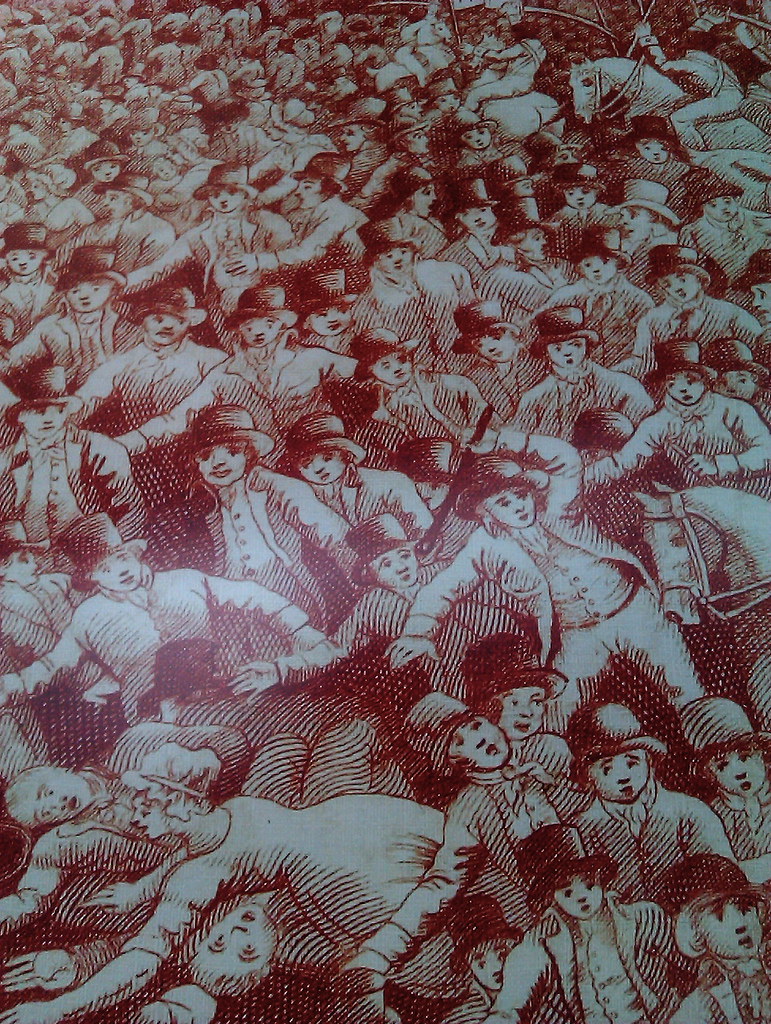

Peterloo massacre (detail). On 16 August 1819, a large political meeting at St Peter's Field, Manchester, in support of parliamentary reform was charged by horseback troops with sabres. 11 people died immediately and others died later: detail from commemorative handkerchief, courtesy of People's History Museum, Manchester; image by Paul Downey via The Guardian, 17 May 2011

Peterloo massacre. On 16 August 1819, a large political meeting at St Peter's Field,

Manchester, in support of parliamentary reform was charged by horseback

troops with sabres. 11 people died immediately and others died later.: commemorative handkerchief, courtesy of People's History Museum, Manchester; image by Paul Downey via The Guardian, 17 May 2011

To

Henry Hunt, Esq., as chairman of the meeting assembled in St. Peter's

Field, Manchester, sixteenth day of August, 1819, and to the female

Reformers of Manchester and the adjacent towns who were exposed to and

suffered from the wanton and fiendish attack made on them by that brutal

armed force, the Manchester and Cheshire Yeomanry Cavalry, this plate

is dedicated by their fellow labourer, Richard Carlile:

a coloured engraving that depicts the Peterloo Massacre (military

suppression of a demonstration in Manchester, England by cavalry charge

on 16 August, with loss of life).

All the poles from which banners are flying have Phrygian caps or

liberty caps on top. Not all the details strictly accord with

contemporary descriptions; the banner the woman is holding should read:

Female Reformers of Roynton -- "Let us die like men and not be sold like

slaves": hand coloured engraving, Richard Carlile (1790–1843), 1 October 1819 (Manchester Library Services)

Peterloo Massacre: print published by Richard Carlile, 1 October 1819; image by Manchester Archives+, 15 August 2011

16 August 1819 -- Peterloo Massacre, Manchester: image by Bradford Timeline, 23 February 2015

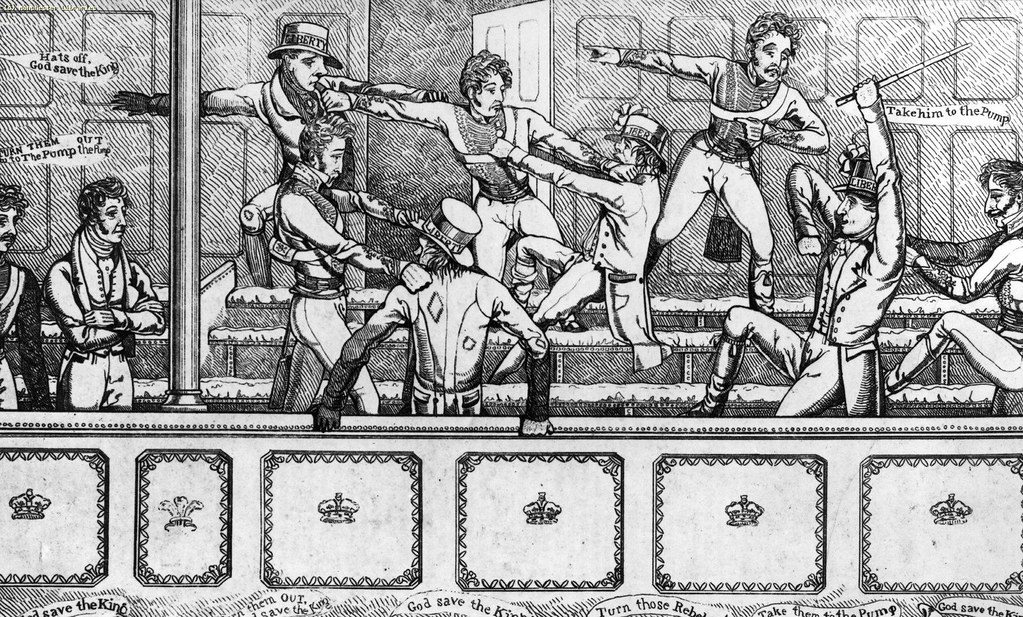

Peterloo Incident in a theatre: Richard Dighton, 1819 (from Annals of Manchester); image by Manchester Archives, 15 August 2011

Looking back at Queen Elizabeth's reign as she becomes UK's longest-serving monarch: image via Reuters Top News @Reuters, 9 September 2015

Oxford Street, in London, is now one of the most polluted in the world.: image via NYT Opinion @nytopinion, 6 November 2015

London Nocturne in Grey and Gold: Snow in Chelsea: James Abbot McNeill Whistler, 1876 (Fogg Museum, Cambridge, Massachusetts)

The unconsummated sacrifice

The fire would not catch, the day was warm, the stench soon became awful

Particles still hang in the air

The Funeral of Shelley: Louis Édouard Fournier (1857-1917), 1889 (Walker Art Gallery, Liverpool); image via poetictouch, 15 September 2014

9 comments:

Thank you for this most excellent post, Tom. The Williams poem is a wonderful tribute to the great Shelley, who indeed lives on.

"An old, mad, blind, despised, and dying King;

Princes, the dregs of their dull race, who flow

Through public scorn . . . "

Tom, thanks for posting Shelley's great poem -- two hundred years ahead of his time.

"When the lamp is shatter'd

The light in the dust lies dead--

When the cloud is scatter'd,

The rainbow's glory is shed."

I very much like your brief

"sacrifice" stanzas. . .wind

blowing the wrong way indeed

remarkable post. . .thanks

tw

The murk in Whistler's Nocturne following from the ashes of failed revolts.

I remember my Dad telling me about the Peterloo massacre when I was around seven years old; a foundational moment in Socialist history (as usual it's our blood on the floor).

Many thanks to all. "The murk in Whistler's Nocturne following from the ashes of failed revolts." Therein lies the gist of this, thank you Duncan. More on the revolting in a minute.

We should keep in mind that whatever revolutionary liberties Shelley may have claimed in his poetry, that claim went unheard outside a small circle of friends, as, being understandably fond of his own liberty, Shelley feared the consequences of publishing the writings he had composed, in a white heat of rage, from a great distance, in the immediate aftermath of Peterloo. England in 1819 is a salient example. And there is the story of The Mask of Anarchy, all 92 verses of it, Shelley's most ambitious poetic response to Peterloo. This work too was to remain unpublished until well after the poet was dead. The manuscript of The Mask was entrusted to Leigh Hunt. Hunt, characteristically, also claimed Shelley's heart from Trelawny, its temporary custodian, after the spectacle of the smoking putrefaction ritual, there on the beach. The poem went from Hunt into print, eventually, when times were more conducive, in 1831. The heart went from Hunt to Mary, but not without a struggle.

The subject of Shelley's Spectacular Romantic Funeral Fail has occasioned centuries of wonderful gossip. Really it requires a woman's clear social mind to unpick the locks that enclose the full humour of this "key moment in Romanticism".

Quoting from Fiona MacCarthy: Byron: Life and Legend:

Shelley's body had been buried... on the beach near Massa. The markings were unclear, and it took about an hour to locate it, by which time Byron and Leigh Hunt had arrived from Pisa, accompanied by two mounted dragoons and four foot soldiers to keep prospective sightseers at bay. The corpse was by then putrid and stinking. Shelley's outer garments were now black. His flesh was of a dingy blue. [Edward] Trelawny started the fire under Shelley's body and, carried away by the grandeur of the scene, offered up his own incantations. 'I restore to nature through fire and the elements of which this man is composed, earth, air, water; everything is changed, but not annihilated; he is now a portion of that which he worshipped.' Byron, standing beside him, said: 'I knew you were a Pagan, not that you were a Pagan Priest; you do it very well.'

[Fiona MacCarthy continues:]

Byron requested that Trelawney should keep Shelley's skull for him, as a memento. Trelawny, remembering that Byron had had a Newstead skull transformed into a drinking cup, had apparently been anxious that Shelley's skull 'should not be so profaned'. In fact the skull disintegrated as Trelawny attempted to remove it from the pyre: 'it broke into pieces -- it was unusually thin and strikingly small.'

There was further controversy over Shelley's heart, which again was particularly small and, in Byron's words, 'would not take the flame'. Trelawney's recollections of the scene provide more details: the heart 'although bedded in fire -- would not burn'. They waited an hour, continually adding fuel, until 'it becoming late we gave over by mutual conviction of its being unavailing -- all exclaiming it will not burn -- there was a bright flame round it occasioned by the moisture still flowing from it -- and on removing the furnace nearer to the sea to immerse the iron I took the heart in my hand to examine it -- after sprinkling it with water: yet it was still so hot as to burn my hand badly and a quantity of this fluid still flowed from it.'

Byron's presence at this agonising scene, which soon came to be regarded as a key moment in Romanticism, has been assumed. In Louis-Edouard Fournier's mid-nineteenth-century oil painting The Cremation of Shelley's Body, Byron is in the forefront of the mourners as a fully clothed, immaculately visaged Shelley is laid out on a bier of firewood on the beach... But in fact during the later stages of the funeral, while the heart of Shelley failed to conflagrate, Byron was almost certainly absent, swimming far out to sea...

While Byron was out of sight, swimming off towards the Bolivar which lay at anchor in the bay, Leigh Hunt had begged from Trelawney Shelley's by now heat-blackened heart. Byron decided, after his return, that Shelley's heart by rights belonged to Mary. Hunt, the next day, wrote indignantly to her: 'With regard to Ld B. he has no right to bestow the heart, & I am sure pretends to none. If he told you that you should have it, it could only have been from his thinking I could more easily part with it than I can.' However Hunt was finally shamed into giving it to Mary. When she died, the heart, by then dry and shrunken, was found in a copy of Adonais.

Richard Holmes' Shelley: The Pursuit makes no mention of the heart, alas: "The bodies of Shelley, Edward Williams, and Charles Vivian were eventually washed up along the beach between Massa and Viareggio ten days after the storm. The exposed flesh of Shelley's arms and face had been entirely eaten away, but he was identifiable by the nankeen trousers, the white silk socks beneath the boots and hunt's copy of Keats's poems doubled back in the jacket pocket. To comply with the complicated quarantine laws, Trelawny had the body temporarily buried in the sand with quick lime, and dug up again on 15 August to be placed in a portable iron furnace that had been constructed to his specification at Livorno, and burnt on the beach in the presence of Leigh Hunt, Lord Byron, some Tuscan militia and a few local fishermen. Much later Shelley's ashes were buried in a tomb, also designed by Trelawny, in the Protestant Cemetery at Rome, after having remained for several months in a mahogany chest in the British Consul's wine-cellar."

another brilliant post Tom, I second what tpw says above and marvel at your energy and devotion to enlightening us all daily with your posts, always grateful

Thanks very much Steve and Michael.

Steve, I believe that in that book and in fact throughout his several magisterial and authoritative works on the Romantics, the spectacles through which Richard Holmes was viewing his subjects may have been ever so slightly rose tinted. Though he and Fiona McC had access to the same material (as do we all, of course), Fiona makes the principals in the scene look more than a little bit silly, which indeed they very much were being... not of course without everyone remaining iconic at every moment, &c. The grand gesture and grand absurdity of it all, & c.

But there are always so many angles to the view, those nearer the ground often more accurate than those from on high. John Keats, whose poems were in Shelley's pocket at the time of his drowning, had while he was yet living actually felt himself being patronized by Shelley, on class grounds -- and, in a gentle but telling way, had reproached Shelley on craft grounds, in reply, advising him to "load every rift with ore" (Keats like not a few others after him questioned the relation between Shelley's highmindedness and his fondness for moving a poem along without quite completing the writing of it), had by sheer chance a low-angle view of Peterloo, yet a view perhaps closer to the event.

That September, a month after the mass meeting at St Peter's Fields in Manchester, K, returning by coach from Walthamstow (where he'd been visiting his sister Fanny), happened to be passing through London just as Henry Hunt, or the Orator Hunt as HH was then called, was making his triumphant entry into the town. A throng of some 300,000 filled the streets from Islington to the Strand. The streets were awash with red flags and red cockades, and in the procession there was even one lad still bandaged-up with sabre wounds inflicted by the Hussars at Peterloo. He sussed the revolutionary spirit in the air, but in these his last months of active composition, his own great contribution was a poem not of revolutionary agitation and excitement, but of recession, concession, resignation, and quiet power, To Autumn, in which every rift is packed with ore.

Keats then, who was a member of that vast underclass whose plight the high-born and privileged "Romantics" were taking up (not without temerity), and in fact lamented to his brother George in the same letter in which he described the Hunt procession that "My name with the literary fashionables is vulgar -- I am a weaver boy to them" (he was thinking about Samuel Bamford), gives us the crowd view, as opposed to the ideal conception from afar.

Post a Comment