Just cancelled my #Nordstrom @Nordstrom #CreditCard to support @POTUS and @IvankaTrump #StandTogether #MAGA #TeamTrump #BusinessandPolitics: image via Cool Hand Mike @captainsugarcu, 8 February 2017

Intel

CEO shows President Trump a 10 nanometer silicon wafer; “the future of

computing,” he says. 7 nanometers will be made in AZ.: image via Bradd Jaffy @BraddJaffy, 8 February 2017

Nick Confessore Retweeted Nick Confessore

Meanwhile, large corporations like Intel understand there a major value in participating in POTUS' job creation theatre.

Nick Confessore added,

Big

increase in traffic into our country from certain areas, while our

people are far more vulnerable, as we wait for what should be EASY D!

Bradd Jaffy Retweeted Donald J. Trump

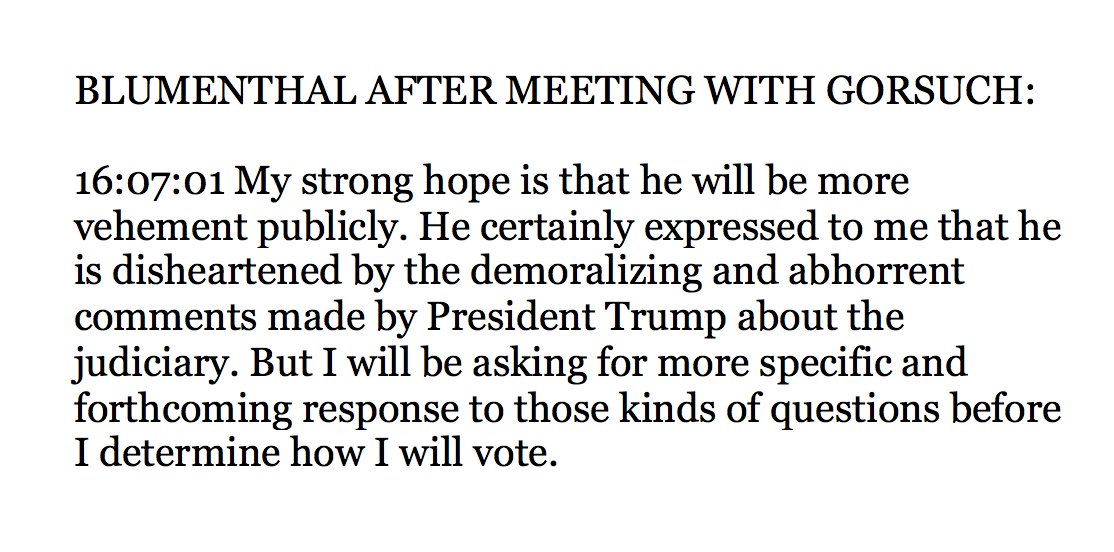

Trump's SCOTUS nominee Neil Gorsuch was “disheartened” by Trump's “demoralizing” remarks about the judiciary, Sen. Blumenthal says after mtg: image via Bradd Jaffy @BraddJaffy, 8 February 2017

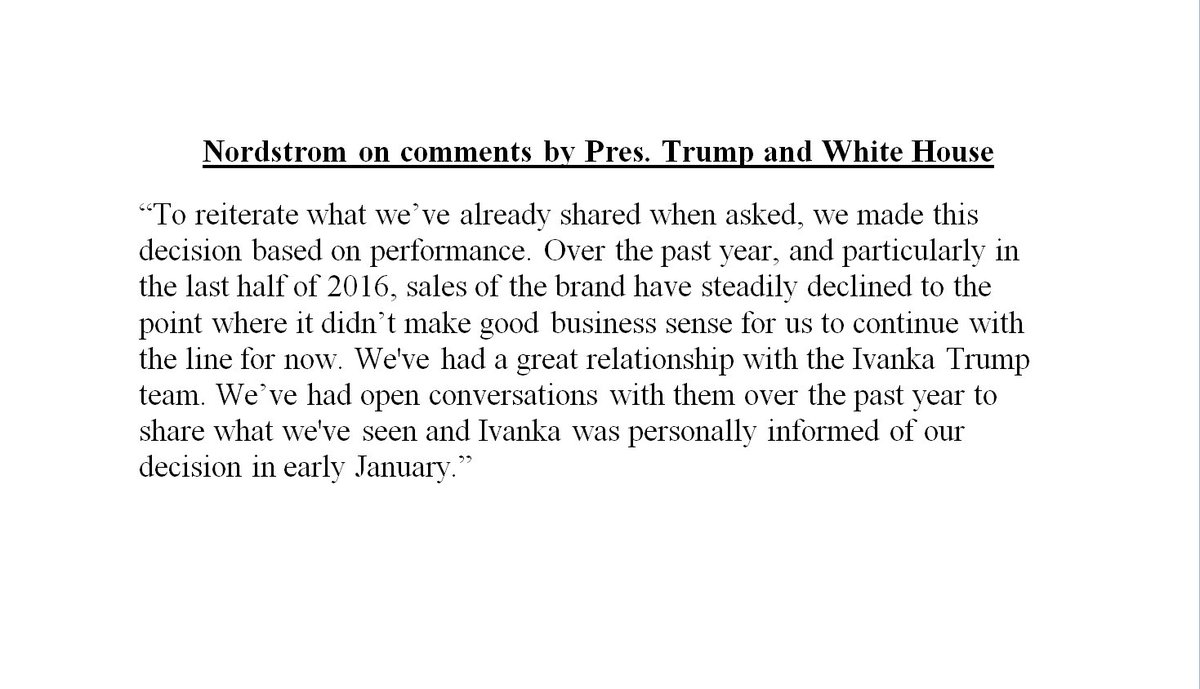

Nordstrom: "We made this decision based on performance" as the Ivanka Trump brand sales declined: "Ivanka was personally informed".: image via NBC Nightly News @NBCNightlyNews, 8 February 2017

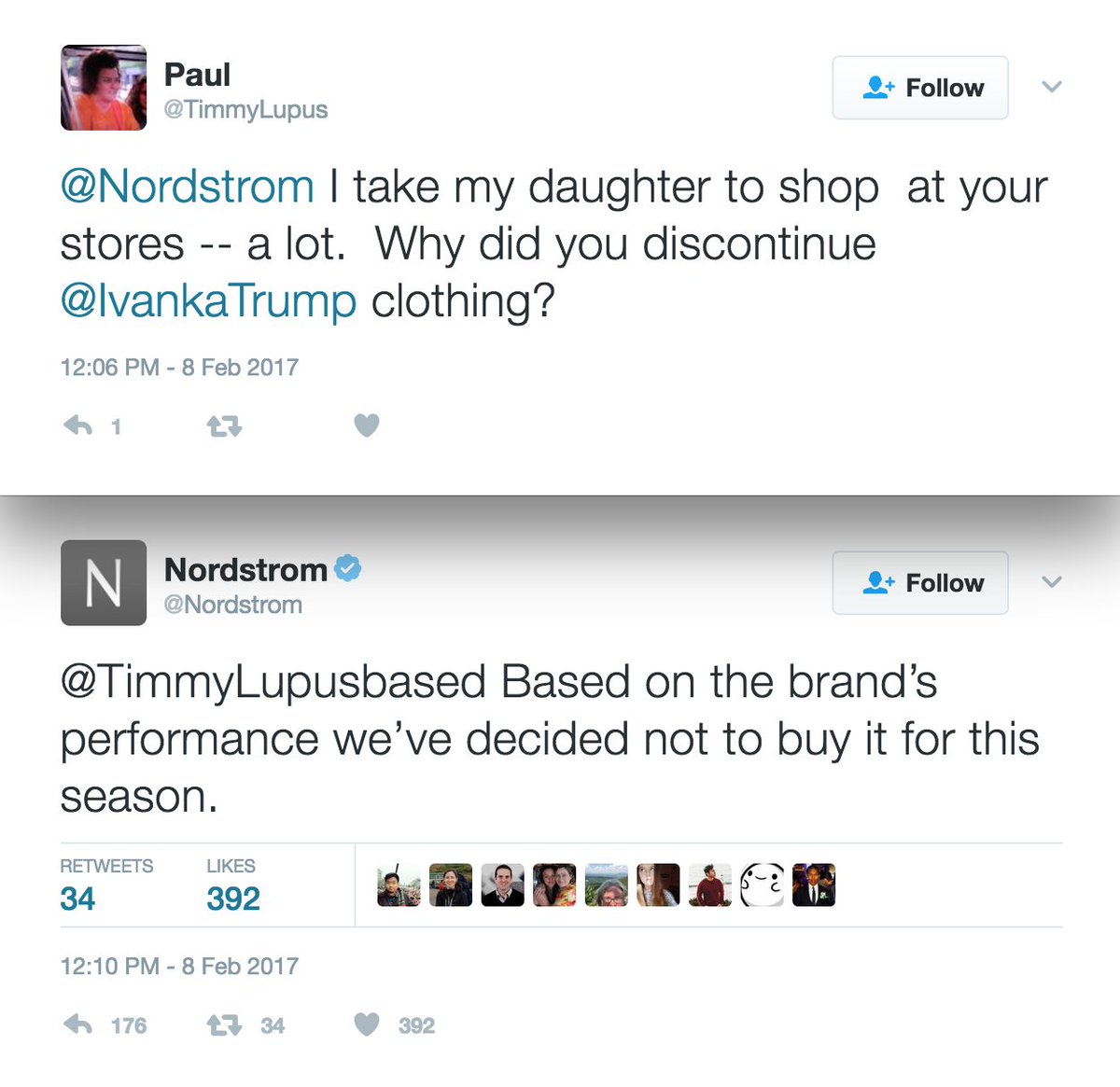

Nordstrom tweets that it decided not to buy Ivanka Trump's fashion line for this season “based on the brand’s performance”: image via Bradd Jaffy @BraddJaffy, 8 February 2017

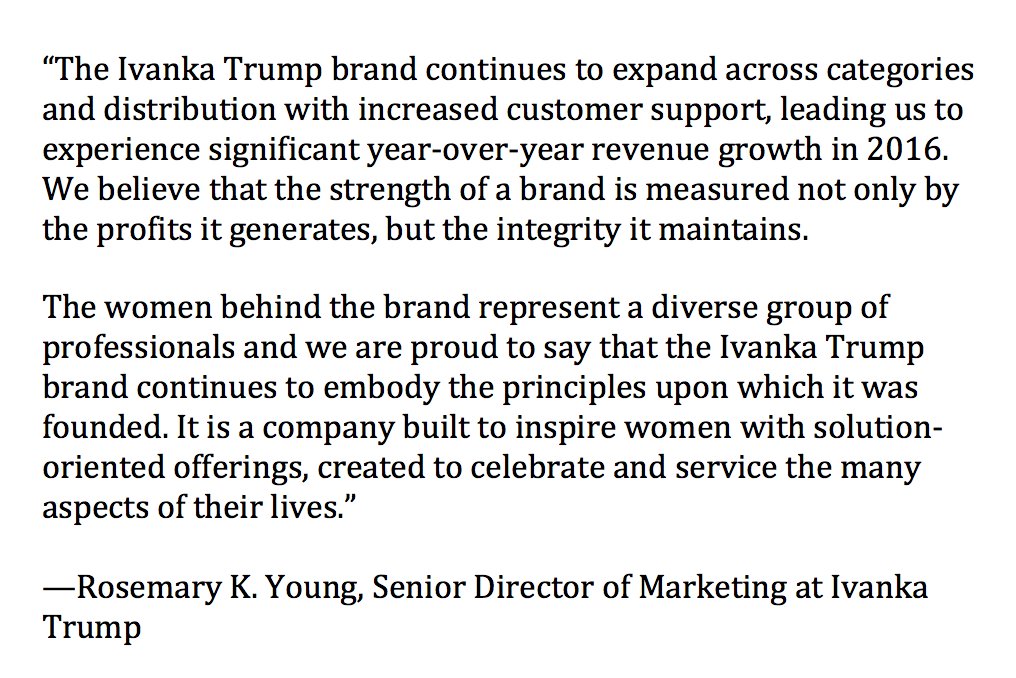

Statement from Rosemary K. Young, Senior Director of Marketing at Ivanka Trump: image via Bradd Jaffy @BraddJaffy, 8 February 2017

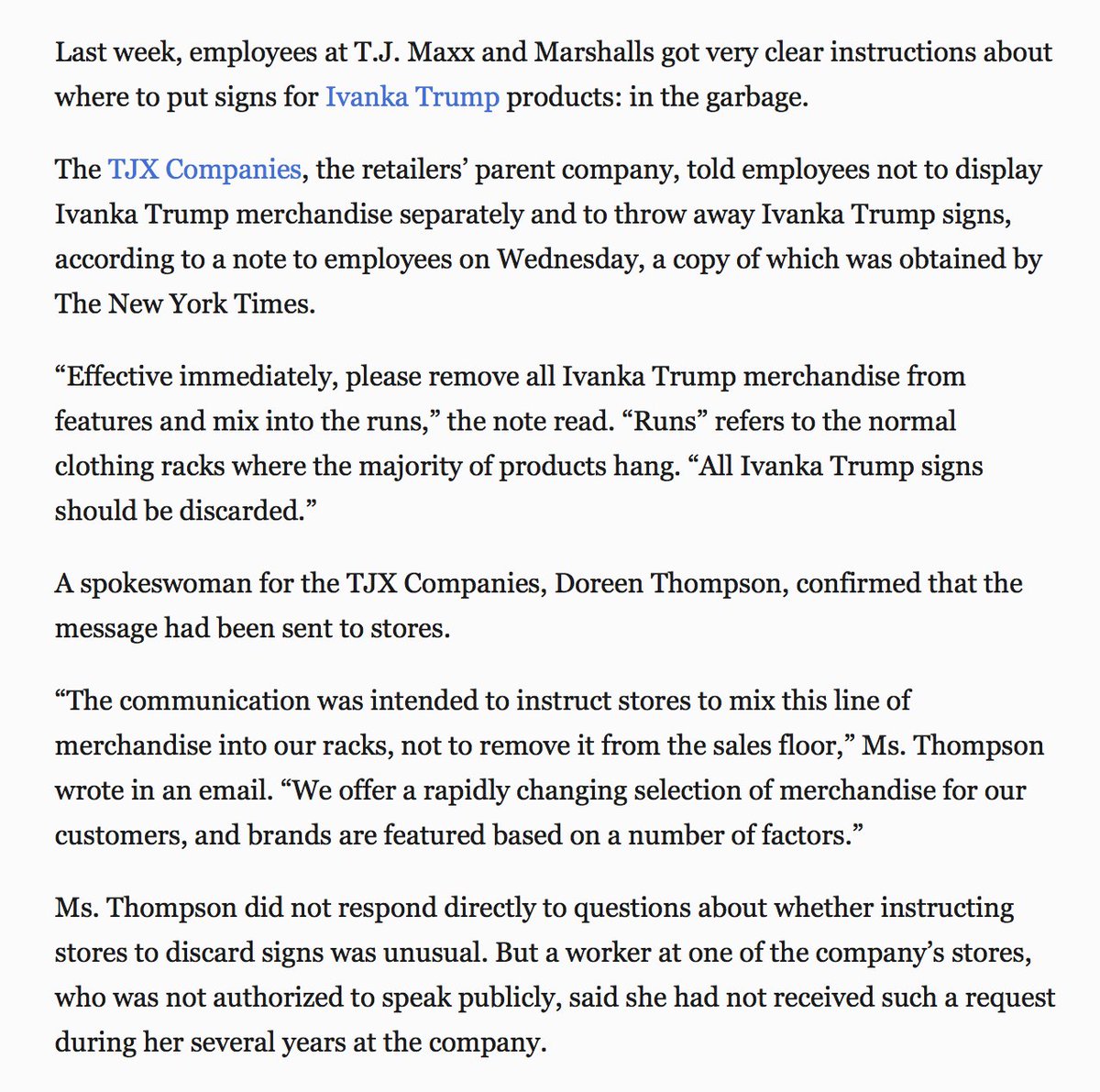

NYT: T.J. Maxx and Marshalls told employees not to display Ivanka Trump products and to throw signs in the garbage: image via Bradd Jaffy @BraddJaffy, 8 February 2017

My daughter Shayna has been treated so unfairly by Zabar's. They sell lox and she's allergic. She is a great person--terrible!: image via John Podhoretz @jpodhoretz, 8 February 2017

@nickconfessore Having run these boycotts before, companies are often loathe to acknowledge dropping because of pressure. Usually cite sales: tweet via John Aravosis @aravosis, 8 February 2017

@nickconfessore Having run these boycotts before, companies are often loathe to acknowledge dropping because of pressure. Usually cite sales: tweet via John Aravosis @aravosis, 8 February 2017

I've never held a political opinion on @Nordstrom before.

That continues to be the case.: tweet via ian bremmer @ianbremmer, 8 February 2017

Money making idea:

Clothing line for Barron: tweet via ian bremmer @ianbremmer, 8 February 2017

Whoever picked Hamilton, Australia and Nordstrom's in the betting pool is really going to cash in.: tweet via Peter W. Singer @peterwsinger, 8 February 2017

Sydney. A sinkhole appeared after heavy rain near PM Malcolm Turnbull’s house. #DontMessWithTrump: image via ian bremmer @ianbremmer, 8 February 2017

Statue of Liberty made from bombed rubble of Aleppo, by Syrian artist Tammam Azzam. Devastating.: tweet via ian bremmer @ianbremmer, 22 October 2016

2017-03. Berkeley, Ca.: photo by biosfear, 1 January 2017

2017-09. Berkeley, Ca.: photo by biosfear, 12 January 2017

2017-18. Berkeley, Ca.: photo by biosfear, January 2017

2017-19. Berkeley, Ca.: photo by biosfear, January 2017

2017-28. Albany, Ca.: photo by biosfear, January 2017

2017-15. Berkeley, Ca.: photo by biosfear, January 2017

More wet #birds in the #rain #berkeley: photo by Buz Murdock Geotag, 18 January 2017

More wet #birds in the #rain #berkeley: photo by Buz Murdock Geotag, 18 January 2017

L'etang est dans le brouillard, tout à coup à gran fracas d'ailes le cygne prend son envoi [Bièvres, Ile-de-France]: photo by René Carrère, 2 November 2015

2017-25. Albany, Ca.: photo by biosfear, January 2017

Keep left [Berkeley]: photo by efo, 3 February 2017

One way to stop it [Thousand Oaks, Berkeley]: photo by efo, 3 February 2017

Berkeley Rain: photo by pnorman4345, 2 February 2017

Julio Cortázar: Axolotl

Norbert is Happy: photo by Cristina, 11 June 2008

Santiago and Norbert: photo by Cristina, 28 April 2008

Santiago and Norbert - "no more pix pls": photo by Cristina, 28 April 2008

Hubo un tiempo en que yo pensaba mucho en los axolotl. Iba a verlos al acuario del Jardín des Plantes y me quedaba horas mirándolos, observando su inmovilidad, sus oscuros movimientos. Ahora soy un axolotl.

El azar me llevó hasta ellos una mañana de primavera en que París abría su cola de pavo real después de la lenta invernada. Bajé por el bulevar de Port Royal, tomé St. Marcel y L’Hôpital, vi los verdes entre tanto gris y me acordé de los leones. Era amigo de los leones y las panteras, pero nunca había entrado en el húmedo y oscuro edificio de los acuarios. Dejé mi bicicleta contra las rejas y fui a ver los tulipanes. Los leones estaban feos y tristes y mi pantera dormía. Opté por los acuarios, soslayé peces vulgares hasta dar inesperadamente con los axolotl. Me quedé una hora mirándolos, y salí incapaz de otra cosa.

En la biblioteca Saint-Geneviève consulté un diccionario y supe que los axolotl son formas larvales, provistas de branquias, de una especie de batracios del género amblistoma. Que eran mexicanos lo sabía ya por ellos mismos, por sus pequeños rostros rosados aztecas y el cartel en lo alto del acuario. Leí que se han encontrado ejemplares en África capaces de vivir en tierra durante los períodos de sequía, y que continúan su vida en el agua al llegar la estación de las lluvias. Encontré su nombre español, ajolote, la mención de que son comestibles y que su aceite se usaba (se diría que no se usa más) como el de hígado de bacalao.

No quise consultar obras especializadas, pero volví al día siguiente al Jardin des Plantes. Empecé a ir todas las mañanas, a veces de mañana y de tarde. El guardián de los acuarios sonreía perplejo al recibir el billete. Me apoyaba en la barra de hierro que bordea los acuarios y me ponía a mirarlos. No hay nada de extraño en esto porque desde un primer momento comprendí que estábamos vinculados, que algo infinitamente perdido y distante seguía sin embargo uniéndonos. Me había bastado detenerme aquella primera mañana ante el cristal donde unas burbujas corrían en el agua. Los axolotl se amontonaban en el mezquino y angosto (sólo yo puedo saber cuán angosto y mezquino) piso de piedra y musgo del acuario. Había nueve ejemplares y la mayoría apoyaba la cabeza contra el cristal, mirando con sus ojos de oro a los que se acercaban. Turbado, casi avergonzado, sentí como una impudicia asomarme a esas figuras silenciosas e inmóviles aglomeradas en el fondo del acuario. Aislé mentalmente una situada a la derecha y algo separada de las otras para estudiarla mejor. Vi un cuerpecito rosado y como translúcido (pensé en las estatuillas chinas de cristal lechoso), semejante a un pequeño lagarto de quince centímetros, terminado en una cola de pez de una delicadeza extraordinaria, la parte más sensible de nuestro cuerpo. Por el lomo le corría una aleta transparente que se fusionaba con la cola, pero lo que me obsesionó fueron las patas, de una finura sutilísima, acabadas en menudos dedos, en uñas minuciosamente humanas. Y entonces descubrí sus ojos, su cara, dos orificios como cabezas de alfiler, enteramente de un oro transparente carentes de toda vida pero mirando, dejándose penetrar por mi mirada que parecía pasar a través del punto áureo y perderse en un diáfano misterio interior. Un delgadísimo halo negro rodeaba el ojo y los inscribía en la carne rosa, en la piedra rosa de la cabeza vagamente triangular pero con lados curvos e irregulares, que le daban una total semejanza con una estatuilla corroída por el tiempo. La boca estaba disimulada por el plano triangular de la cara, sólo de perfil se adivinaba su tamaño considerable; de frente una fina hendedura rasgaba apenas la piedra sin vida. A ambos lados de la cabeza, donde hubieran debido estar las orejas, le crecían tres ramitas rojas como de coral, una excrescencia vegetal, las branquias supongo. Y era lo único vivo en él, cada diez o quince segundos las ramitas se enderezaban rígidamente y volvían a bajarse. A veces una pata se movía apenas, yo veía los diminutos dedos posándose con suavidad en el musgo. Es que no nos gusta movernos mucho, y el acuario es tan mezquino; apenas avanzamos un poco nos damos con la cola o la cabeza de otro de nosotros; surgen dificultades, peleas, fatiga. El tiempo se siente menos si nos estamos quietos.

Fue su quietud la que me hizo inclinarme fascinado la primera vez que vi a los axolotl. Oscuramente me pareció comprender su voluntad secreta, abolir el espacio y el tiempo con una inmovilidad indiferente. Después supe mejor, la contracción de las branquias, el tanteo de las finas patas en las piedras, la repentina natación (algunos de ellos nadan con la simple ondulación del cuerpo) me probó que eran capaz de evadirse de ese sopor mineral en el que pasaban horas enteras. Sus ojos sobre todo me obsesionaban. Al lado de ellos en los restantes acuarios, diversos peces me mostraban la simple estupidez de sus hermosos ojos semejantes a los nuestros. Los ojos de los axolotl me decían de la presencia de una vida diferente, de otra manera de mirar. Pegando mi cara al vidrio (a veces el guardián tosía inquieto) buscaba ver mejor los diminutos puntos áureos, esa entrada al mundo infinitamente lento y remoto de las criaturas rosadas. Era inútil golpear con el dedo en el cristal, delante de sus caras no se advertía la menor reacción. Los ojos de oro seguían ardiendo con su dulce, terrible luz; seguían mirándome desde una profundidad insondable que me daba vértigo.

Y sin embargo estaban cerca. Lo supe antes de esto, antes de ser un axolotl. Lo supe el día en que me acerqué a ellos por primera vez. Los rasgos antropomórficos de un mono revelan, al revés de lo que cree la mayoría, la distancia que va de ellos a nosotros. La absoluta falta de semejanza de los axolotl con el ser humano me probó que mi reconocimiento era válido, que no me apoyaba en analogías fáciles. Sólo las manecitas... Pero una lagartija tiene también manos así, y en nada se nos parece. Yo creo que era la cabeza de los axolotl, esa forma triangular rosada con los ojitos de oro. Eso miraba y sabía. Eso reclamaba. No eran animales.

Parecía fácil, casi obvio, caer en la mitología. Empecé viendo en los axolotl una metamorfosis que no conseguía anular una misteriosa humanidad. Los imaginé conscientes, esclavos de su cuerpo, infinitamente condenados a un silencio abisal, a una reflexión desesperada. Su mirada ciega, el diminuto disco de oro inexpresivo y sin embargo terriblemente lúcido, me penetraba como un mensaje: «Sálvanos, sálvanos». Me sorprendía musitando palabras de consuelo, transmitiendo pueriles esperanzas. Ellos seguían mirándome inmóviles; de pronto las ramillas rosadas de las branquias de enderezaban. En ese instante yo sentía como un dolor sordo; tal vez me veían, captaban mi esfuerzo por penetrar en lo impenetrable de sus vidas. No eran seres humanos, pero en ningún animal había encontrado una relación tan profunda conmigo. Los axolotl eran como testigos de algo, y a veces como horribles jueces. Me sentía innoble frente a ellos, había una pureza tan espantosa en esos ojos transparentes. Eran larvas, pero larva quiere decir máscara y también fantasma. Detrás de esas caras aztecas inexpresivas y sin embargo de una crueldad implacable, ¿qué imagen esperaba su hora?

Les temía. Creo que de no haber sentido la proximidad de otros visitantes y del guardián, no me hubiese atrevido a quedarme solo con ellos. «Usted se los come con los ojos», me decía riendo el guardián, que debía suponerme un poco desequilibrado. No se daba cuenta de que eran ellos los que me devoraban lentamente por los ojos en un canibalismo de oro. Lejos del acuario no hacía mas que pensar en ellos, era como si me influyeran a distancia. Llegué a ir todos los días, y de noche los imaginaba inmóviles en la oscuridad, adelantando lentamente una mano que de pronto encontraba la de otro. Acaso sus ojos veían en plena noche, y el día continuaba para ellos indefinidamente. Los ojos de los axolotl no tienen párpados.

Ahora sé que no hubo nada de extraño, que eso tenía que ocurrir. Cada mañana al inclinarme sobre el acuario el reconocimiento era mayor. Sufrían, cada fibra de mi cuerpo alcanzaba ese sufrimiento amordazado, esa tortura rígida en el fondo del agua. Espiaban algo, un remoto señorío aniquilado, un tiempo de libertad en que el mundo había sido de los axolotl. No era posible que una expresión tan terrible que alcanzaba a vencer la inexpresividad forzada de sus rostros de piedra, no portara un mensaje de dolor, la prueba de esa condena eterna, de ese infierno líquido que padecían. Inútilmente quería probarme que mi propia sensibilidad proyectaba en los axolotl una conciencia inexistente. Ellos y yo sabíamos. Por eso no hubo nada de extraño en lo que ocurrió. Mi cara estaba pegada al vidrio del acuario, mis ojos trataban una vez mas de penetrar el misterio de esos ojos de oro sin iris y sin pupila. Veía de muy cerca la cara de una axolotl inmóvil junto al vidrio. Sin transición, sin sorpresa, vi mi cara contra el vidrio, en vez del axolotl vi mi cara contra el vidrio, la vi fuera del acuario, la vi del otro lado del vidrio. Entonces mi cara se apartó y yo comprendí.

Sólo una cosa era extraña: seguir pensando como antes, saber. Darme cuenta de eso fue en el primer momento como el horror del enterrado vivo que despierta a su destino. Afuera mi cara volvía a acercarse al vidrio, veía mi boca de labios apretados por el esfuerzo de comprender a los axolotl. Yo era un axolotl y sabía ahora instantáneamente que ninguna comprensión era posible. Él estaba fuera del acuario, su pensamiento era un pensamiento fuera del acuario. Conociéndolo, siendo él mismo, yo era un axolotl y estaba en mi mundo. El horror venía -lo supe en el mismo momento- de creerme prisionero en un cuerpo de axolotl, transmigrado a él con mi pensamiento de hombre, enterrado vivo en un axolotl, condenado a moverme lúcidamente entre criaturas insensibles. Pero aquello cesó cuando una pata vino a rozarme la cara, cuando moviéndome apenas a un lado vi a un axolotl junto a mí que me miraba, y supe que también él sabía, sin comunicación posible pero tan claramente. O yo estaba también en él, o todos nosotros pensábamos como un hombre, incapaces de expresión, limitados al resplandor dorado de nuestros ojos que miraban la cara del hombre pegada al acuario.

Él volvió muchas veces, pero viene menos ahora. Pasa semanas sin asomarse. Ayer lo vi, me miró largo rato y se fue bruscamente. Me pareció que no se interesaba tanto por nosotros, que obedecía a una costumbre. Como lo único que hago es pensar, pude pensar mucho en él. Se me ocurre que al principio continuamos comunicados, que él se sentía más que nunca unido al misterio que lo obsesionaba. Pero los puentes están cortados entre él y yo porque lo que era su obsesión es ahora un axolotl, ajeno a su vida de hombre. Creo que al principio yo era capaz de volver en cierto modo a él -ah, sólo en cierto modo-, y mantener alerta su deseo de conocernos mejor. Ahora soy definitivamente un axolotl, y si pienso como un hombre es sólo porque todo axolotl piensa como un hombre dentro de su imagen de piedra rosa. Me parece que de todo esto alcancé a comunicarle algo en los primeros días, cuando yo era todavía él. Y en esta soledad final, a la que él ya no vuelve, me consuela pensar que acaso va a escribir sobre nosotros, creyendo imaginar un cuento va a escribir todo esto sobre los axolotl.

There

was a time when I thought a great deal about the axolotls. I went to

see them in the aquarium at the

Jardin des Plantes and stayed for hours watching them, observing their

immobility, their faint

movements. Now I am an axolotl.

I got to them by chance one spring morning when Paris was spreading its peacock tail after a slow wintertime. I was heading down tbe boulevard Port-Royal, then I took Saint-Marcel and L'Hôpital and saw green among all that grey and remembered the lions. I was friend of the lions and panthers, but had never gone into the dark, humid building that was the aquarium. I left my bike against tbe gratings and went to look at the tulips. The lions were sad and ugly and my panther was asleep. I decided on the aquarium, looked obliquely at banal fish until, unexpectedly, I hit it off with the axolotls. I stayed watching them for an hour and left, unable to think of anything else.

In the library at Sainte-Geneviève, I consulted a dictionary and learned that axolotls are the larval stage (provided with gills) of a species of salamander of the genus Ambystoma. That they were Mexican I knew already by looking at them and their little pink Aztec faces and the placard at the top of the tank. I read that specimens of them had been found in Africa capable of living on dry land during the periods of drought, and continuing their life under water when the rainy season came. I found their Spanish name, ajolote, and the mention that they were edible, and that their oil was used (no longer used, it said ) like cod-liver oil.

I didn't care to look up any of the specialized works, but the next day I went back to the Jardin des Plantes. I began to go every morning, morning and aftemoon some days. The aquarium guard smiled perplexedly taking my ticket. I would lean up against the iron bar in front of the tanks and set to watching them. There's nothing strange in this, because after the first minute I knew that we were linked, that something infinitely lost and distant kept pulling us together. It had been enough to detain me that first morning in front of the sheet of glass where some bubbles rose through the water. The axolotls huddled on the wretched narrow (only I can know how narrow and wretched) floor of moss and stone in the tank. There were nine specimens, and the majority pressed their heads against the glass, looking with their eyes of gold at whoever came near them. Disconcerted, almost ashamed, I felt it a lewdness to be peering at these silent and immobile figures heaped at the bottom of the tank.

Mentally I isolated one, situated on the right and somewhat apart from the others, to study it better. I saw a rosy little body, translucent (I thought of those Chinese figurines of milky glass), looking like a small lizard about six inches long, ending in a fish's tail of extraordinary delicacy, the most sensitive part of our body. Along the back ran a transparent fin which joined with the tail, but what obsessed me was the feet, of the slenderest nicety, ending in tiny fingers with minutely human nails. And then I discovered its eyes, its face. Inexpressive features, with no other trait save the eyes, two orifices, like brooches, wholly of transparent gold, lacking any life but looking, letting themselves be penetrated by my look, which seemed to travel past the golden level and lose itself in a diaphanous interior mystery. A very slender black halo ringed the eye and etched it onto the pink flesh, onto the rosy stone of the head, vaguely triangular, but with curved and triangular sides which gave it a total likeness to a statuette corroded by time. The mouth was masked by the triangular plane of the face, its considerable size would be guessed only in profile; in front a delicate crevice barely slit the lifeless stone. On both sides of the head where the ears should have been, there grew three tiny sprigs, red as coral, a vegetal outgrowth, the gills, I suppose. And they were the only thing quick about it; every ten or fifteen seconds the sprigs pricked up stiffly and again subsided. Once in a while a foot would barely move, I saw the diminutive toes poise mildly on the moss. It's that we don't enjoy moving a lot, and the tank is so cramped—we barely move in any direction and we're hitting one of the others with our tail or our head—difficulties arise, fights, tiredness. The time feels like it's less if we stay quietly.

It was their quietness that made me lean toward them fascinated the first time I saw the axolotls. Obscurely I seemed to understand their secret will, to abolish space and time with an indifferent immobility. I knew better later; the gill contraction, the tentative reckoning of the delicate feet on the stones, the abrupt swimming (some of them swim with a simple undulation of the body) proved to me that they were capable of escaping that mineral lethargy in which they spent whole hours. Above all else, their eyes obsessed me. In the standing tanks on either side of them, different fishes showed me the simple stupidity of their handsome eyes so similar to our own. The eyes of the axolotls spoke to me of the presence of a different life, of another way of seeing. Glueing my face to the glass (the guard would cough fussily once in a while), I tried to see better those diminutive golden points, that entrance to the infinitely slow and remote world of these rosy creatures. It was useless to tap with one finger on the glass directly in front of their faces; they never gave the least reaction. The golden eyes continued burning with their soft, terrible light; they continued looking at me from an unfathomable depth which made me dizzy.

And nevertheless they were close. I knew it before this, before being an axolotl. I learned it the day I came near them for the first time. The anthropomorphic features of a monkey reveal the reverse of what most people believe, the distance that is traveled from them to us. The absolute lack of similarity between axolotls and human beings proved to me that my recognition was valid, that I was not propping myself up with easy analogies. Only the little hands . . . But an eft, the common newt, has such hands also, and we are not at all alike. I think it was the axolotls' heads, that triangular pink shape with the tiny eyes of gold. That looked and knew. That laid the claim. They were not animals.

It would seem easy, almost obvious, to fall into mythology. I began seeing in the axolotls a metamorphosis which did not succeed in revoking a mysterious humanity. I imagined them aware, slaves of their bodies, condemned infinitely to the silence of the abyss, to a hopeless meditation. Their blind gaze, the diminutive gold disc without expression and nonetheless terribly shining, went through me like a message: "Save us, save us." I caught myself mumbling words of advice, conveying childish hopes. They continued to look at me, immobile; from time to time the rosy branches of the gills stiffened. In that instant I felt a muted pain; perhaps they were seeing me, attracting my strength to penetrate into the impenetrable thing of their lives. They were not human beings, but I had found in no animal such a profound relation with myself. The axolotls were like witnesses of something, and at times like horrible judges. I felt ignoble in front of them; there was such a terrifying purity in those transparent eyes. They were larvas, but larva means disguise and also phantom. Behind those Aztec faces, without expression but of an implacable cruelty, what semblance was awaiting its hour?

I was afraid of them. I think that had it not been for feeling the proximity of other visitors and the guard, I would not have been bold enough to remain alone with them. "You eat them alive with your eyes, hey," the guard said, laughing; he likely thought I was a little cracked. What he didn't notice was that it was they devouring me slowly with their eyes, in a cannibalism of gold. At any distance from the aquarium, I had only to think of them, it was as though I were being affected from a distance. It got to the point that I was going every day, and at night I thought of them immobile in the darkness, slowly putting a hand out which immediately encountered another. Perhaps their eyes could see in the dead of night, and for them the day continued indefinitely. The eyes of axolotls have no lids.

I know now that there was nothing strange, that that had to occur. Leaning over in front of the tank each morning, the recognition was greater. They were suffering, every fiber of my body reached toward that stifled pain, that stiff torment at the bottom of the tank. They were lying in wait for something, a remote dominion destroyed, an age of liberty when the world had been that of the axolotls. Not possible that such a terrible expression which was attaining the overthrow of that forced blankness on their stone faces should carry any message other than one of pain, proof of that eternal sentence, of that liquid hell they were undergoing. Hopelessly, I wanted to prove to myself that my own sensibility was projecting a nonexistent consciousness upon the axolotls. They and I knew. So there was nothing strange in what happened. My face was pressed against the glass of the aquarium, my eyes were attempting once more to penetrate the mystery of those eyes of gold without iris, without pupil. I saw from very close up the face of an axolotl immobile next to the glass. No transition and no surprise, I saw my face against the glass, I saw it on the outside of the tank, I saw it on the other side of the glass. Then my face drew back and I understood.

Only one thing was strange: to go on thinking as usual, to know. To realize that was, for the first moment, like the horror of a man buried alive awaking to his fate. Outside, my face came close to the glass again, I saw my mouth, the lips compressed with the effort of understanding the axolotls. I was an axolotl and now I knew instantly that no understanding was possible. He was outside the aquarium, his thinking was a thinking outside the tank. Recognizlng him, being him himself, I was an axolotl and in my world. The horror began—I learned in the same moment—of believing myself prisoner in the body of an axolotl, metamorphosed into him with my human mind intact, buried alive in an axolotl, condemned to move lucidly among unconscious creatures. But that stopped when a foot just grazed my face, when I moved just a little to one side and saw an axolotl next to me who was looking at me, and understood that he knew also, no communication possible, but very clearly. Or I was also in him, or all of us were thinking humanlike, incapable of expression, limited to the golden splendor of our eyes looking at the face of the man pressed against the aquarium.

He returned many times, but he comes less often now. Weeks pass without his showing up. I saw him yesterday, he looked at me for a long time and left briskly. It seemed to me that he was not so much interested in us any more, that he was coming out of habit. Since the only thing I do is think, I could think about him a lot. It occurs to me that at the beginning we continued to communicate, that he felt more than ever one with the mystery which was claiming him. But the bridges were broken between him and me, because what was his obsession is now an axolotl, alien to his human life. I think that at the beginning I was capable of returning to him in a certain way—ah, only in a certain way—and of keeping awake his desire to know us better. I am an axolotl for good now, and if I think like a man it's only because every axolotl thinks like a man inside his rosy stone semblance. I believe that all this succeeded in communicating something to him in those first days, when I was still he. And in this final solitude to which he no longer comes, I console myself by thinking that perhaps he is going to write a story about us, that, believing he's making up a story, he's going to write all this about axolotls.

Axolotl (Ambystoma mexicana), leucistic: photo by Orizatriz, 2009

Axolotls (Ambystoma mexicana), leucistic: photo by ZeWrestler, 2010

Axolotl (Ambystoma mexicana), leucistic: photo by Nicolas Guérin, 2008

Norbert is Happy: photo by Cristina, 11 June 2008

Santiago and Norbert: photo by Cristina, 28 April 2008

Santiago and Norbert - "no more pix pls": photo by Cristina, 28 April 2008

Hubo un tiempo en que yo pensaba mucho en los axolotl. Iba a verlos al acuario del Jardín des Plantes y me quedaba horas mirándolos, observando su inmovilidad, sus oscuros movimientos. Ahora soy un axolotl.

El azar me llevó hasta ellos una mañana de primavera en que París abría su cola de pavo real después de la lenta invernada. Bajé por el bulevar de Port Royal, tomé St. Marcel y L’Hôpital, vi los verdes entre tanto gris y me acordé de los leones. Era amigo de los leones y las panteras, pero nunca había entrado en el húmedo y oscuro edificio de los acuarios. Dejé mi bicicleta contra las rejas y fui a ver los tulipanes. Los leones estaban feos y tristes y mi pantera dormía. Opté por los acuarios, soslayé peces vulgares hasta dar inesperadamente con los axolotl. Me quedé una hora mirándolos, y salí incapaz de otra cosa.

En la biblioteca Saint-Geneviève consulté un diccionario y supe que los axolotl son formas larvales, provistas de branquias, de una especie de batracios del género amblistoma. Que eran mexicanos lo sabía ya por ellos mismos, por sus pequeños rostros rosados aztecas y el cartel en lo alto del acuario. Leí que se han encontrado ejemplares en África capaces de vivir en tierra durante los períodos de sequía, y que continúan su vida en el agua al llegar la estación de las lluvias. Encontré su nombre español, ajolote, la mención de que son comestibles y que su aceite se usaba (se diría que no se usa más) como el de hígado de bacalao.

No quise consultar obras especializadas, pero volví al día siguiente al Jardin des Plantes. Empecé a ir todas las mañanas, a veces de mañana y de tarde. El guardián de los acuarios sonreía perplejo al recibir el billete. Me apoyaba en la barra de hierro que bordea los acuarios y me ponía a mirarlos. No hay nada de extraño en esto porque desde un primer momento comprendí que estábamos vinculados, que algo infinitamente perdido y distante seguía sin embargo uniéndonos. Me había bastado detenerme aquella primera mañana ante el cristal donde unas burbujas corrían en el agua. Los axolotl se amontonaban en el mezquino y angosto (sólo yo puedo saber cuán angosto y mezquino) piso de piedra y musgo del acuario. Había nueve ejemplares y la mayoría apoyaba la cabeza contra el cristal, mirando con sus ojos de oro a los que se acercaban. Turbado, casi avergonzado, sentí como una impudicia asomarme a esas figuras silenciosas e inmóviles aglomeradas en el fondo del acuario. Aislé mentalmente una situada a la derecha y algo separada de las otras para estudiarla mejor. Vi un cuerpecito rosado y como translúcido (pensé en las estatuillas chinas de cristal lechoso), semejante a un pequeño lagarto de quince centímetros, terminado en una cola de pez de una delicadeza extraordinaria, la parte más sensible de nuestro cuerpo. Por el lomo le corría una aleta transparente que se fusionaba con la cola, pero lo que me obsesionó fueron las patas, de una finura sutilísima, acabadas en menudos dedos, en uñas minuciosamente humanas. Y entonces descubrí sus ojos, su cara, dos orificios como cabezas de alfiler, enteramente de un oro transparente carentes de toda vida pero mirando, dejándose penetrar por mi mirada que parecía pasar a través del punto áureo y perderse en un diáfano misterio interior. Un delgadísimo halo negro rodeaba el ojo y los inscribía en la carne rosa, en la piedra rosa de la cabeza vagamente triangular pero con lados curvos e irregulares, que le daban una total semejanza con una estatuilla corroída por el tiempo. La boca estaba disimulada por el plano triangular de la cara, sólo de perfil se adivinaba su tamaño considerable; de frente una fina hendedura rasgaba apenas la piedra sin vida. A ambos lados de la cabeza, donde hubieran debido estar las orejas, le crecían tres ramitas rojas como de coral, una excrescencia vegetal, las branquias supongo. Y era lo único vivo en él, cada diez o quince segundos las ramitas se enderezaban rígidamente y volvían a bajarse. A veces una pata se movía apenas, yo veía los diminutos dedos posándose con suavidad en el musgo. Es que no nos gusta movernos mucho, y el acuario es tan mezquino; apenas avanzamos un poco nos damos con la cola o la cabeza de otro de nosotros; surgen dificultades, peleas, fatiga. El tiempo se siente menos si nos estamos quietos.

Fue su quietud la que me hizo inclinarme fascinado la primera vez que vi a los axolotl. Oscuramente me pareció comprender su voluntad secreta, abolir el espacio y el tiempo con una inmovilidad indiferente. Después supe mejor, la contracción de las branquias, el tanteo de las finas patas en las piedras, la repentina natación (algunos de ellos nadan con la simple ondulación del cuerpo) me probó que eran capaz de evadirse de ese sopor mineral en el que pasaban horas enteras. Sus ojos sobre todo me obsesionaban. Al lado de ellos en los restantes acuarios, diversos peces me mostraban la simple estupidez de sus hermosos ojos semejantes a los nuestros. Los ojos de los axolotl me decían de la presencia de una vida diferente, de otra manera de mirar. Pegando mi cara al vidrio (a veces el guardián tosía inquieto) buscaba ver mejor los diminutos puntos áureos, esa entrada al mundo infinitamente lento y remoto de las criaturas rosadas. Era inútil golpear con el dedo en el cristal, delante de sus caras no se advertía la menor reacción. Los ojos de oro seguían ardiendo con su dulce, terrible luz; seguían mirándome desde una profundidad insondable que me daba vértigo.

Y sin embargo estaban cerca. Lo supe antes de esto, antes de ser un axolotl. Lo supe el día en que me acerqué a ellos por primera vez. Los rasgos antropomórficos de un mono revelan, al revés de lo que cree la mayoría, la distancia que va de ellos a nosotros. La absoluta falta de semejanza de los axolotl con el ser humano me probó que mi reconocimiento era válido, que no me apoyaba en analogías fáciles. Sólo las manecitas... Pero una lagartija tiene también manos así, y en nada se nos parece. Yo creo que era la cabeza de los axolotl, esa forma triangular rosada con los ojitos de oro. Eso miraba y sabía. Eso reclamaba. No eran animales.

Parecía fácil, casi obvio, caer en la mitología. Empecé viendo en los axolotl una metamorfosis que no conseguía anular una misteriosa humanidad. Los imaginé conscientes, esclavos de su cuerpo, infinitamente condenados a un silencio abisal, a una reflexión desesperada. Su mirada ciega, el diminuto disco de oro inexpresivo y sin embargo terriblemente lúcido, me penetraba como un mensaje: «Sálvanos, sálvanos». Me sorprendía musitando palabras de consuelo, transmitiendo pueriles esperanzas. Ellos seguían mirándome inmóviles; de pronto las ramillas rosadas de las branquias de enderezaban. En ese instante yo sentía como un dolor sordo; tal vez me veían, captaban mi esfuerzo por penetrar en lo impenetrable de sus vidas. No eran seres humanos, pero en ningún animal había encontrado una relación tan profunda conmigo. Los axolotl eran como testigos de algo, y a veces como horribles jueces. Me sentía innoble frente a ellos, había una pureza tan espantosa en esos ojos transparentes. Eran larvas, pero larva quiere decir máscara y también fantasma. Detrás de esas caras aztecas inexpresivas y sin embargo de una crueldad implacable, ¿qué imagen esperaba su hora?

Les temía. Creo que de no haber sentido la proximidad de otros visitantes y del guardián, no me hubiese atrevido a quedarme solo con ellos. «Usted se los come con los ojos», me decía riendo el guardián, que debía suponerme un poco desequilibrado. No se daba cuenta de que eran ellos los que me devoraban lentamente por los ojos en un canibalismo de oro. Lejos del acuario no hacía mas que pensar en ellos, era como si me influyeran a distancia. Llegué a ir todos los días, y de noche los imaginaba inmóviles en la oscuridad, adelantando lentamente una mano que de pronto encontraba la de otro. Acaso sus ojos veían en plena noche, y el día continuaba para ellos indefinidamente. Los ojos de los axolotl no tienen párpados.

Ahora sé que no hubo nada de extraño, que eso tenía que ocurrir. Cada mañana al inclinarme sobre el acuario el reconocimiento era mayor. Sufrían, cada fibra de mi cuerpo alcanzaba ese sufrimiento amordazado, esa tortura rígida en el fondo del agua. Espiaban algo, un remoto señorío aniquilado, un tiempo de libertad en que el mundo había sido de los axolotl. No era posible que una expresión tan terrible que alcanzaba a vencer la inexpresividad forzada de sus rostros de piedra, no portara un mensaje de dolor, la prueba de esa condena eterna, de ese infierno líquido que padecían. Inútilmente quería probarme que mi propia sensibilidad proyectaba en los axolotl una conciencia inexistente. Ellos y yo sabíamos. Por eso no hubo nada de extraño en lo que ocurrió. Mi cara estaba pegada al vidrio del acuario, mis ojos trataban una vez mas de penetrar el misterio de esos ojos de oro sin iris y sin pupila. Veía de muy cerca la cara de una axolotl inmóvil junto al vidrio. Sin transición, sin sorpresa, vi mi cara contra el vidrio, en vez del axolotl vi mi cara contra el vidrio, la vi fuera del acuario, la vi del otro lado del vidrio. Entonces mi cara se apartó y yo comprendí.

Sólo una cosa era extraña: seguir pensando como antes, saber. Darme cuenta de eso fue en el primer momento como el horror del enterrado vivo que despierta a su destino. Afuera mi cara volvía a acercarse al vidrio, veía mi boca de labios apretados por el esfuerzo de comprender a los axolotl. Yo era un axolotl y sabía ahora instantáneamente que ninguna comprensión era posible. Él estaba fuera del acuario, su pensamiento era un pensamiento fuera del acuario. Conociéndolo, siendo él mismo, yo era un axolotl y estaba en mi mundo. El horror venía -lo supe en el mismo momento- de creerme prisionero en un cuerpo de axolotl, transmigrado a él con mi pensamiento de hombre, enterrado vivo en un axolotl, condenado a moverme lúcidamente entre criaturas insensibles. Pero aquello cesó cuando una pata vino a rozarme la cara, cuando moviéndome apenas a un lado vi a un axolotl junto a mí que me miraba, y supe que también él sabía, sin comunicación posible pero tan claramente. O yo estaba también en él, o todos nosotros pensábamos como un hombre, incapaces de expresión, limitados al resplandor dorado de nuestros ojos que miraban la cara del hombre pegada al acuario.

Él volvió muchas veces, pero viene menos ahora. Pasa semanas sin asomarse. Ayer lo vi, me miró largo rato y se fue bruscamente. Me pareció que no se interesaba tanto por nosotros, que obedecía a una costumbre. Como lo único que hago es pensar, pude pensar mucho en él. Se me ocurre que al principio continuamos comunicados, que él se sentía más que nunca unido al misterio que lo obsesionaba. Pero los puentes están cortados entre él y yo porque lo que era su obsesión es ahora un axolotl, ajeno a su vida de hombre. Creo que al principio yo era capaz de volver en cierto modo a él -ah, sólo en cierto modo-, y mantener alerta su deseo de conocernos mejor. Ahora soy definitivamente un axolotl, y si pienso como un hombre es sólo porque todo axolotl piensa como un hombre dentro de su imagen de piedra rosa. Me parece que de todo esto alcancé a comunicarle algo en los primeros días, cuando yo era todavía él. Y en esta soledad final, a la que él ya no vuelve, me consuela pensar que acaso va a escribir sobre nosotros, creyendo imaginar un cuento va a escribir todo esto sobre los axolotl.

I got to them by chance one spring morning when Paris was spreading its peacock tail after a slow wintertime. I was heading down tbe boulevard Port-Royal, then I took Saint-Marcel and L'Hôpital and saw green among all that grey and remembered the lions. I was friend of the lions and panthers, but had never gone into the dark, humid building that was the aquarium. I left my bike against tbe gratings and went to look at the tulips. The lions were sad and ugly and my panther was asleep. I decided on the aquarium, looked obliquely at banal fish until, unexpectedly, I hit it off with the axolotls. I stayed watching them for an hour and left, unable to think of anything else.

In the library at Sainte-Geneviève, I consulted a dictionary and learned that axolotls are the larval stage (provided with gills) of a species of salamander of the genus Ambystoma. That they were Mexican I knew already by looking at them and their little pink Aztec faces and the placard at the top of the tank. I read that specimens of them had been found in Africa capable of living on dry land during the periods of drought, and continuing their life under water when the rainy season came. I found their Spanish name, ajolote, and the mention that they were edible, and that their oil was used (no longer used, it said ) like cod-liver oil.

I didn't care to look up any of the specialized works, but the next day I went back to the Jardin des Plantes. I began to go every morning, morning and aftemoon some days. The aquarium guard smiled perplexedly taking my ticket. I would lean up against the iron bar in front of the tanks and set to watching them. There's nothing strange in this, because after the first minute I knew that we were linked, that something infinitely lost and distant kept pulling us together. It had been enough to detain me that first morning in front of the sheet of glass where some bubbles rose through the water. The axolotls huddled on the wretched narrow (only I can know how narrow and wretched) floor of moss and stone in the tank. There were nine specimens, and the majority pressed their heads against the glass, looking with their eyes of gold at whoever came near them. Disconcerted, almost ashamed, I felt it a lewdness to be peering at these silent and immobile figures heaped at the bottom of the tank.

Mentally I isolated one, situated on the right and somewhat apart from the others, to study it better. I saw a rosy little body, translucent (I thought of those Chinese figurines of milky glass), looking like a small lizard about six inches long, ending in a fish's tail of extraordinary delicacy, the most sensitive part of our body. Along the back ran a transparent fin which joined with the tail, but what obsessed me was the feet, of the slenderest nicety, ending in tiny fingers with minutely human nails. And then I discovered its eyes, its face. Inexpressive features, with no other trait save the eyes, two orifices, like brooches, wholly of transparent gold, lacking any life but looking, letting themselves be penetrated by my look, which seemed to travel past the golden level and lose itself in a diaphanous interior mystery. A very slender black halo ringed the eye and etched it onto the pink flesh, onto the rosy stone of the head, vaguely triangular, but with curved and triangular sides which gave it a total likeness to a statuette corroded by time. The mouth was masked by the triangular plane of the face, its considerable size would be guessed only in profile; in front a delicate crevice barely slit the lifeless stone. On both sides of the head where the ears should have been, there grew three tiny sprigs, red as coral, a vegetal outgrowth, the gills, I suppose. And they were the only thing quick about it; every ten or fifteen seconds the sprigs pricked up stiffly and again subsided. Once in a while a foot would barely move, I saw the diminutive toes poise mildly on the moss. It's that we don't enjoy moving a lot, and the tank is so cramped—we barely move in any direction and we're hitting one of the others with our tail or our head—difficulties arise, fights, tiredness. The time feels like it's less if we stay quietly.

It was their quietness that made me lean toward them fascinated the first time I saw the axolotls. Obscurely I seemed to understand their secret will, to abolish space and time with an indifferent immobility. I knew better later; the gill contraction, the tentative reckoning of the delicate feet on the stones, the abrupt swimming (some of them swim with a simple undulation of the body) proved to me that they were capable of escaping that mineral lethargy in which they spent whole hours. Above all else, their eyes obsessed me. In the standing tanks on either side of them, different fishes showed me the simple stupidity of their handsome eyes so similar to our own. The eyes of the axolotls spoke to me of the presence of a different life, of another way of seeing. Glueing my face to the glass (the guard would cough fussily once in a while), I tried to see better those diminutive golden points, that entrance to the infinitely slow and remote world of these rosy creatures. It was useless to tap with one finger on the glass directly in front of their faces; they never gave the least reaction. The golden eyes continued burning with their soft, terrible light; they continued looking at me from an unfathomable depth which made me dizzy.

And nevertheless they were close. I knew it before this, before being an axolotl. I learned it the day I came near them for the first time. The anthropomorphic features of a monkey reveal the reverse of what most people believe, the distance that is traveled from them to us. The absolute lack of similarity between axolotls and human beings proved to me that my recognition was valid, that I was not propping myself up with easy analogies. Only the little hands . . . But an eft, the common newt, has such hands also, and we are not at all alike. I think it was the axolotls' heads, that triangular pink shape with the tiny eyes of gold. That looked and knew. That laid the claim. They were not animals.

It would seem easy, almost obvious, to fall into mythology. I began seeing in the axolotls a metamorphosis which did not succeed in revoking a mysterious humanity. I imagined them aware, slaves of their bodies, condemned infinitely to the silence of the abyss, to a hopeless meditation. Their blind gaze, the diminutive gold disc without expression and nonetheless terribly shining, went through me like a message: "Save us, save us." I caught myself mumbling words of advice, conveying childish hopes. They continued to look at me, immobile; from time to time the rosy branches of the gills stiffened. In that instant I felt a muted pain; perhaps they were seeing me, attracting my strength to penetrate into the impenetrable thing of their lives. They were not human beings, but I had found in no animal such a profound relation with myself. The axolotls were like witnesses of something, and at times like horrible judges. I felt ignoble in front of them; there was such a terrifying purity in those transparent eyes. They were larvas, but larva means disguise and also phantom. Behind those Aztec faces, without expression but of an implacable cruelty, what semblance was awaiting its hour?

I was afraid of them. I think that had it not been for feeling the proximity of other visitors and the guard, I would not have been bold enough to remain alone with them. "You eat them alive with your eyes, hey," the guard said, laughing; he likely thought I was a little cracked. What he didn't notice was that it was they devouring me slowly with their eyes, in a cannibalism of gold. At any distance from the aquarium, I had only to think of them, it was as though I were being affected from a distance. It got to the point that I was going every day, and at night I thought of them immobile in the darkness, slowly putting a hand out which immediately encountered another. Perhaps their eyes could see in the dead of night, and for them the day continued indefinitely. The eyes of axolotls have no lids.

I know now that there was nothing strange, that that had to occur. Leaning over in front of the tank each morning, the recognition was greater. They were suffering, every fiber of my body reached toward that stifled pain, that stiff torment at the bottom of the tank. They were lying in wait for something, a remote dominion destroyed, an age of liberty when the world had been that of the axolotls. Not possible that such a terrible expression which was attaining the overthrow of that forced blankness on their stone faces should carry any message other than one of pain, proof of that eternal sentence, of that liquid hell they were undergoing. Hopelessly, I wanted to prove to myself that my own sensibility was projecting a nonexistent consciousness upon the axolotls. They and I knew. So there was nothing strange in what happened. My face was pressed against the glass of the aquarium, my eyes were attempting once more to penetrate the mystery of those eyes of gold without iris, without pupil. I saw from very close up the face of an axolotl immobile next to the glass. No transition and no surprise, I saw my face against the glass, I saw it on the outside of the tank, I saw it on the other side of the glass. Then my face drew back and I understood.

Only one thing was strange: to go on thinking as usual, to know. To realize that was, for the first moment, like the horror of a man buried alive awaking to his fate. Outside, my face came close to the glass again, I saw my mouth, the lips compressed with the effort of understanding the axolotls. I was an axolotl and now I knew instantly that no understanding was possible. He was outside the aquarium, his thinking was a thinking outside the tank. Recognizlng him, being him himself, I was an axolotl and in my world. The horror began—I learned in the same moment—of believing myself prisoner in the body of an axolotl, metamorphosed into him with my human mind intact, buried alive in an axolotl, condemned to move lucidly among unconscious creatures. But that stopped when a foot just grazed my face, when I moved just a little to one side and saw an axolotl next to me who was looking at me, and understood that he knew also, no communication possible, but very clearly. Or I was also in him, or all of us were thinking humanlike, incapable of expression, limited to the golden splendor of our eyes looking at the face of the man pressed against the aquarium.

He returned many times, but he comes less often now. Weeks pass without his showing up. I saw him yesterday, he looked at me for a long time and left briskly. It seemed to me that he was not so much interested in us any more, that he was coming out of habit. Since the only thing I do is think, I could think about him a lot. It occurs to me that at the beginning we continued to communicate, that he felt more than ever one with the mystery which was claiming him. But the bridges were broken between him and me, because what was his obsession is now an axolotl, alien to his human life. I think that at the beginning I was capable of returning to him in a certain way—ah, only in a certain way—and of keeping awake his desire to know us better. I am an axolotl for good now, and if I think like a man it's only because every axolotl thinks like a man inside his rosy stone semblance. I believe that all this succeeded in communicating something to him in those first days, when I was still he. And in this final solitude to which he no longer comes, I console myself by thinking that perhaps he is going to write a story about us, that, believing he's making up a story, he's going to write all this about axolotls.

Axolotl (Ambystoma mexicana), leucistic: photo by Orizatriz, 2009

Axolotl (Ambystoma mexicana), leucistic: photo by Orizatriz, 2009

Axolotl (Ambystoma mexicana), leucistic: photo by Olivier Pouzin, 2007

Axolotls (Ambystoma mexicana), leucistic: photo by ZeWrestler, 2010

Axolotl (Ambystoma mexicana), leucistic: photo by Monika Korzeniec, 2006

Axolotl (Ambystoma mexicana), leucistic: photo by Nicolas Guérin, 2008

Julio Cortázar (1914-1984): Axolotl, from Final del juego (1956); English version by Paul Blackburn

In the swamp

In the swamp

2017-03. Berkeley, Ca.: photo by biosfear, 1 January 2017

2017-09. Berkeley, Ca.: photo by biosfear, 12 January 2017

2017-17. Berkeley, Ca.: photo by biosfear, January 2017

2017-18. Berkeley, Ca.: photo by biosfear, January 2017

2017-19. Berkeley, Ca.: photo by biosfear, January 2017

2017-28. Albany, Ca.: photo by biosfear, January 2017

2017-15. Berkeley, Ca.: photo by biosfear, January 2017

More wet #birds in the #rain #berkeley: photo by Buz Murdock Geotag, 18 January 2017

More wet #birds in the #rain #berkeley: photo by Buz Murdock Geotag, 18 January 2017

L'etang est dans le brouillard, tout à coup à gran fracas d'ailes le cygne prend son envoi [Bièvres, Ile-de-France]: photo by René Carrère, 2 November 2015

2017-25. Albany, Ca.: photo by biosfear, January 2017

Keep left [Berkeley]: photo by efo, 3 February 2017

One way to stop it [Thousand Oaks, Berkeley]: photo by efo, 3 February 2017

Berkeley Rain: photo by pnorman4345, 2 February 2017

1 comment:

Julio Cortázar: Axolotl

Post a Comment